“Whatever the mind can conceive and believe, it can achieve.”

“Whatever the mind can conceive and believe, it can achieve.”

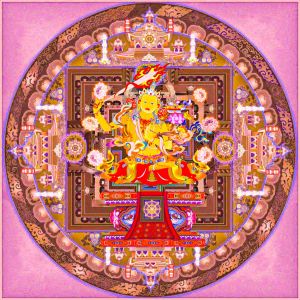

A thangka, variously spelt as thangka, tangka, thanka, or tanka (Nepali pronunciation: [???????]; Tibetan: ?????; Nepal Bhasa: ????), is a Tibetan Buddhist painting on cotton, silk appliqué, usually depicting a Buddhist deity, scene, or mandala.

Thangkas are traditionally kept unframed and rolled up when not on display, mounted on a textile backing somewhat in the style of Chinese scroll paintings, with a further silk cover on the front. So treated, thangkas can last a long time, but because of their delicate nature, they have to be kept in dry places where moisture will not affect the quality of the silk.

Most thangkas are relatively small, comparable in size to a Western half-length portrait, but some are extremely large, several metres in each dimension; these were designed to be displayed, typically for very brief periods on a monastery wall, as part of religious festivals.

Most thangkas were intended for personal meditation or instruction of monastic students. They often have elaborate compositions including many very small figures. A central deity is often surrounded by other identified figures in a symmetrical composition. Narrative scenes are less common, but do appear.

Thangka serve as important teaching tools depicting the life of the Buddha, various influential lamas and other deities and bodhisattvas. One subject is The Wheel of Life (Bhavachakra), which is a visual representation of the Abhidharma teachings (Art of Enlightenment).

The term may sometimes be used of works in other media than painting, including reliefs in metal and woodblock prints. Today printed reproductions at poster size of painted thangka are commonly used for devotional as well as decorative purposes. Many tangkas were produced in sets, though they have often subsequently become separated.

Thangka perform several different functions. Images of deities can be used as teaching tools when depicting the life (or lives) of the Buddha, describing historical events concerning important Lamas, or retelling myths associated with other deities.

Devotional images act as the centerpiece during a ritual or ceremony and are often used as mediums through which one can offer prayers or make requests. Overall, and perhaps most importantly, religious art is used as a meditation tool to help bring one further down the path to enlightenment.

The Buddhist Vajrayana practitioner uses a thanka image of their yidam, or meditation deity, as a guide, by visualizing "themselves as being that deity, thereby internalizing the Buddha qualities"[1] tangkas hang on or beside altars, and may be hung in the bedrooms or offices of monks and other devotees.

Types

Based on technique and material, tangkas can be grouped by types. Generally, they are divided into two broad categories: those that are painted (Tib.) bris-tan—and those made of silk, either by appliqué or embroidery.

Tangkas are further divided into these more specific categories:

Painted in colours (Tib.) tson-tang—the most common type

Black Background—meaning gold line on a black background (Tib.) nagtang

Blockprints—paper or cloth outlined renderings, by woodcut/woodblock printing

Embroidery (Tib.) tsem-thang

Gold Background—an auspicious treatment, used judiciously for peaceful, long-life deities and fully enlightened buddhas

Red Background—literally gold line, but referring to gold line on a vermillion (Tib.) mar-tang

and thangka images generally fall into 11 categories:

1) mandalas,

2) Tsokshing (Assembly Trees), 3) Tathagata Buddhas,

4) Patriarchs,

5) Avoliteshvara,

6) Buddha-Mother and female Bodhisattvas, 7) tutelary deities,

8) dharma-protecting deities,

9) Arhats.

and 10) wrathful deities;

and 11) other Bodhisattvas.

One popular subject is The Wheel of Life, which is a visual representation of the Abhidharma teachings (Art of Enlightenment). Devotional images act as the centerpiece during a ritual or ceremony and are often used as mediums through which one can offer prayers or make requests.

Overall, and perhaps most importantly, religious art is used as a meditation tool to help bring one further down the path to enlightenment. The Buddhist Vajrayana practitioner uses a thanga image of their yidam, or meditation deity, as a guide, by visualizing “themselves as being that deity, thereby internalizing the Buddha qualities (Lipton, Ragnubs)."

Whereas typical tangkas are fairly small, with painted area between about 20 to 50 centimetres high, there are also giant festival tangkas, usually appliqué, and designed to be unrolled against a wall in a monastery for particular religious occasions.

These are likely to be wider than they are tall, and may be sixty or more feet across and perhaps twenty or more high. In Bhutan at least these are called thongdrels. There are also larger than average thankas that were designed for altars or display in temples.

Somewhat related are Tibetan tsakli, cards which look like miniature tangkas perhaps up to 15 centimetres high, and often square, usually containing a single figure. These were mostly produced in sets and were usually used in earlier stages of training monks, or as initiation cards or offerings, or to use when constructing temporary mandalas.

Another related form is the painted wooden top cover for a manuscript book, giving a long narrow strip, typically some 6 cm by 55 cm, often painted with a row of seated figures in compartments. The techniques for both these forms are essentially the same as for thangka, and presumably the same artists worked on them. Because tangkas can be quite expensive, people nowadays use posters of tangkas as an alternative to the real tangkas for religious purposes.

Sources on Asian art often describe all-textile tangkas as "tapestry", but tangkas that meet the normal definition of tapestry with the image created only by weaving a single piece of fabric with different colours of thread are extremely rare, though a few tapestry examples in the Chinese kesi technique are known, mostly from the medieval period. There is a large example in the Hermitage Museum, although in this and other pieces the different colours are woven separately and then sewn together in a type of patchwork. Most thangka described as tapestry are some combination of embroidery, appliqué and other techniques.

Most old thangka have inscriptions on the back, usually the mantra of the deity depicted, but sometimes also information as to later owners, though rarely information about the original commissioner or artist. Sometimes x-rays allow pious inscriptions placed under the paint on the front of the image to be seen. Inscriptions may be made in the shape of a stupa, or sometimes other shapes.[16]

The composition of a thangka, as with the majority of Buddhist art, is highly geometric

The technique of visualization is employed throughout the Vajrayana practices of Tibetan Buddhism. Its use of our imagination makes it quite different from other meditations, such as shamatha, or calm abiding.

Imagination also plays a major part in our deluded experience of life. Everything we encounter and perceive in our daily life is a product of our imagination, but because we believe in the illusions we create, they become such deeply rooted mental habits that we completely forget they are little more than fantasy. T

he imagination is therefore one of our most powerful tools, and working with it by changing the ways we look at our world is what we call the practice of visualization.

One small problem for beginners is that the English word visualization can be misleading. Most people think visualization means focusing on an image and then holding it in their mind’s eye. But physical appearance is only one element of visualization practice, and by no means the whole story.

Peoples’ attitudes and understanding change according to their situations and education. Until very recently, Buddhist masters brought up in Tibet would have looked on salad and green vegetables as animal fodder and would never have willingly eaten it themselves.

Now that Tibetans have become familiar with food outside of Tibet, their attitudes have changed, and it is precisely this kind of shift in our perception that we work with in our visualization, which is also called “creation meditation.”

According to Vajrayana theory, your perception of this world is unique; it is not seen or experienced in the same way by anyone else because what you see does not exist externally.

The main purpose of visualization practice is to purify our ordinary, impure perception of the phenomenal world by developing “pure perception.” Unfortunately, though, pure perception is yet another notion that tends to be misunderstood.

Students often try to re-create a photographic image of a Tibetan painting in their mind, with two-dimensional deities who never blink, surrounded by clouds frozen in space, and with consorts who look like grown-up babies.

Practicing this erroneous version of visualization instills in you a far worse form of perception than the one you were born with, and in the process the whole point of pure perception is destroyed.

On a deeper level thangka paintings can be seen as a visual expression of the highest state of consciousness, which is the ultimate goal of the Buddhist spiritual path. This is why a thangka is sometimes called a ‘roadmap to enlightenment’, as it shows you the way to this fully awakened state of enlightenment.

“The third development of visualization is vividness. There is a direct relationship between how clearly you can see your desired goal or result in your mind and how quickly it comes into your reality. This element of visualization is what explains the powers of the Law of Attraction and the Law of Correspondence. The vividness of your desire directly determines how quickly your goal materializes in the world around you.

In order to understand the various levels and usages of visualization, first we need to throw the word visualization out of the window. It is the wrong word because the word visualization implies something visual. In other words, it implies working with visual images and it also implies working with our eyes.

This is incorrect. Instead, we are working with the imagination. When we work with the imagination we’re not only working with imagined sights, but also with imagined sounds, smells, physical sensations, feelings – emotional feelings – and so on.

Obviously, we do that with our minds, not with our eyes. If we think of the Western psychological division of the brain into a right side and a left side, Tibetan Buddhism develops both sides – both the intellectual, rational side and the side of creative imagination.

Therefore, when we speak of visualization in Buddhism, we’re not talking about some magical process. We’re talking about something quite practical, in terms of how to develop and use all our potentials, because we have potentials on both the right and left sides of the brain. When we work with the imagination, we’re dealing with creativity, artistic aspects and so on.

We work with the imagination on many different levels. We can divide these into sutra methods and tantra methods. Of these two, those of tantra are the most advanced.

Deity yoga (Tibetan: lha'i rnal 'byor; Sanskrit: Devata-yoga) is a practice of Vajrayana Buddhism involving identification with a chosen deity through visualisations and rituals, and the realisation of emptiness. According to the Tibetan scholar Tsongkhapa, deity yoga is what separates Buddhist Tantra practice from the practice of other Buddhist schools.

Deity yoga involves two stages, the generation stage and the completion stage. In the generation stage, one dissolves the mundane world and visualizes one's chosen deity (yidam), its mandala and companion deities, resulting in identification with this divine reality.

In the completion stage, one dissolves the visualization of and identification with the yidam in the realization of sunyata or emptiness. Completion stage practices can also include subtle body energy practices

Representations of the deity, such as a statues, paintings (Tibetan: thangka), or mandalas, are often employed as an aid to visualization in both the Generation Stage (Tibetan: Kye-rim) and the Completion Stage (Tibetan: Dzog-rim) of Anuttarayoga Tantra.

he mandalas are symbolic representations of sacred enclosures, sacred architecture that house and contain the uncontainable essence of a yidam. In the book, The World of Tibetan Buddhism, the Dalai Lama describes a mandala: “This is the celestial mansion, the pure residence of the deity.

Front generation

Front generation is a form of meditative visualization employed in Tantric Buddhism in which the yidam is visualized as being present in the sky facing the practitioner as opposed to the self-identification that occurs in self generation. According to the Vajrayana tradition, this approach is considered less advanced, hence safer for the sadhaka, and is engaged more for the rites of propitiation and worship

Self generation

Self generation is a form of meditative visualization employed in Tantric Buddhism in which the yidam is invoked and then merged with the sadhaka as an upaya of self-transformation. This is as opposed to the method of front generation. According to the Vajrayana tradition, self generation is held to be more advanced and accompanied by a degree of spiritual risk from the siddhi it may rapidly yield.[

An important element of this is "divine pride", which is "the thought that one is oneself the deity being visualized."

According to John Powers, "divine pride is different from ordinary, afflicted pride because it is motivated by compassion for others and is based on an understanding of emptiness. T

the deity and oneself are both known to be empty, all appearances are viewed as manifestations of the luminous and empty nature of mind, and so the divine pride of deity yoga does not lead to attachment, greed, and other afflictions."

On the complete stage, we cause the energy-winds (rlung, Skt. prana) to enter, abide, and dissolve in the central channel. This enables us to access the subtlest level of mental activity (clear light, ‘ od-gsal) and use it for the nonconceptual cognition of voidness – the immediate cause for the omniscient mind of a Buddha.

We use the subtlest level of energy-wind, which supports clear light mental activity, to arise in the form of an illusory body (sgyu-lus) as the immediate cause for the network of form bodies (Skt. rupakaya) of a Buddha.

[T]he completion stage defined as the dissolving of the visualization of a deity corresponds to Mahayoga; the "Completion stage with marks" based on yogic practices such as tummo corresponds to Anu Yoga: and the "Completion stage without marks" is the practice of Ati Yoga.

One of the richest visual objects in Tibetan Buddhism is the mandala.

A mandala is a symbolic picture of the universe. It can be a painting on a wall or scroll, created in coloured sands on a table, or a visualisation in the mind of a very skilled adept.

The mandala represents an imaginary palace that is contemplated during meditation. Each object in the palace has significance, representing an aspect of wisdom or reminding the meditator of a guiding principle. The mandala's purpose is to help transform ordinary minds into enlightened ones and to assist with healing.

A mandala is a form of Buddhist prayer and art that is usually associated with a particular Buddha and his ascension to enlightenment. Regarded as a powerful center of psychic energy, it symbolizes the macrocosm of the universe, the miniature universe of the practitioner and the platform on which the Buddha addresses his followers.

The design for the mandala is said to have been brought to Tibet by the legendary 1,000-year-old lama, Guru Rinpoche, in the Each Ox Year of 749

Mandalas can be painted, constructed of stone, embroidered, sculptured or even serve as the layout plan for entire monasteries.. Most are painstakingly made from sand, preferably sand made from millions of grains of crushed, vegetable'died marble. The tradition of making mandalas is said to be derived from ancient folk religions and Hinduism. Today mandalas are mostly made by followers of Tantric Buddhism.

Lama Tsongkhapa explained mandala offerings in the Lam-rim Chen-mo.

Buddhists use mandalas as aids for mediation. Both making a mandala and gazing at one are regarded as forms of meditation. The Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung called mandalas universal maps of the human subconscious and "antidotes for the chaotic states of mind." He said their circular shape was a symbol of the divine.

Mandalas have three levels:

1) the outer level representing the universe;

2) the inner level showing the route to enlightenment;

and the 3) secret level depicting the balance between the body and mind. Each shape is said to contain an attribute of a deity, and sometimes these shapes are used to forecast the future.

Mandalas aid individuals in visualizing various celestial Buddha realms.

Two dimensional ones are regarded as part of the three'dimensional world of the central figure and a microcosm of the universe. During meditation a user using a mandala as a visual aid focuses on the deity, visualizing up to 722 deities associated with it, with the deity disappearing into nothingness and re-emerging as the deity. To do this takes extraordinary concentration.

All the enjoyments in all the realms is the result. There are two ways to visualize numberless offerings—you can do both. Visualize offerings on every atom (like Samantabhadra) and then from each of those atoms, beams are emitted and carry mandala offerings that fill the sky and become numberless. Everything you visualize should be big, huge!

Three-Dimensional Mandalas

Three'dimensional mandalas look like elaborately-sculpted wooden wedding cakes and sometimes take years to make. Some of them are representation of the Shi-Tro mandala, a mansion for deities with so much power it can release any person from his or her negative karma. Many three'dimensional mandalas were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.

"The floor doors to the palace, for instance, represent the 'four immeasurables' of loving kindness, compassion, equanimity and joy. There are lion beams signifying strength and a fire circle in which all negative forces are burned and transformed into wisdom."

The main circular area contains a diagram of a palace with four elaborately decorated gateways. This structure should be imagined as three'dimensional. From the square base, the palace rises up as a pyramid and is topped by a circle within a square containing the major deity,

Visualisation of Vajrayana teachings

The mandala can be shown to represent in visual form the core essence of the Vajrayana teachings. The mind is "a microcosm representing various divine powers at work in the universe."[11] The mandala represents the nature of the Pure Land, Enlightened mind.

While on the one hand, the mandala is regarded as a place separated and protected from the ever-changing and impure outer world of samsara, and is thus seen as a "Buddhafield" or a place of Nirvana and peace, the view of Vajrayana Buddhism sees the greatest protection from samsara being the power to see samsaric confusion as the "shadow" of purity (which then points towards it)

A mandala can also represent the entire universe, which is traditionally depicted with Mount Meru as the axis mundi in the center, surrounded by the continents.

Wisdom and impermanence

In the mandala, the outer circle of fire usually symbolises wisdom. The ring of eight charnel grounds[15] represents the Buddhist exhortation to be always mindful of death, and the impermanence with which samsara is suffused: "such locations were utilized in order to confront and to realize the transient nature of life."

Described elsewhere: "within a flaming rainbow nimbus and encircled by a black ring of dorjes, the major outer ring depicts the eight great charnel grounds, to emphasize the dangerous nature of human life." Inside these rings lie the walls of the mandala palace itself, specifically a place populated by deities and Buddhas.

One well-known type of mandala is the mandala of the "Five Buddhas", archetypal Buddha forms embodying various aspects of enlightenment. Such Buddhas are depicted depending on the school of Buddhism, and even the specific purpose of the mandala. A common mandala of this type is that of the Five Wisdom Buddhas (a.k.a. Five Jinas), the Buddhas Vairocana, Aksobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha and Amoghasiddhi. When paired with another mandala depicting the Five Wisdom Kings, this forms the Mandala of the Two Realms.

Practice

Mandalas are commonly used by tantric Buddhists as an aid to meditation.

The mandala is "a support for the meditating person", something to be repeatedly contemplated to the point of saturation, such that the image of the mandala becomes fully internalised in even the minutest detail and can then be summoned and contemplated at will as a clear and vivid visualized image.

With every mandala comes what Tucci calls "its associated liturgy [...] contained in texts known as tantras",[ instructing practitioners on how the mandala should be drawn, built and visualised, and indicating the mantras to be recited during its ritual use.

By visualizing "pure lands", one learns to understand experience itself as pure, and as the abode of enlightenment. The protection that we need, in this view, is from our own minds, as much as from external sources of confusion.

In many tantric mandalas, this aspect of separation and protection from the outer samsaric world is depicted by "the four outer circles: the purifying fire of wisdom, the vajra circle, the circle with the eight tombs, the lotus circle." The ring of vajras forms a connected fence-like arrangement running around the perimeter of the outer mandala circle.[

As a meditation on impermanence (a central teaching of Buddhism), after days or weeks of creating the intricate pattern of a sand mandala, the sand is brushed together into a pile and spilled into a body of running water to spread the blessings of the mandala.

Chenrezig sand mandala created at the House of Commons of the United Kingdom on the occasion of the Dalai Lama's visit in May 2008

A "mandala offering" in Tibetan Buddhism is a symbolic offering of the entire universe. Every intricate detail of these mandalas is fixed in the tradition and has specific symbolic meanings, often on more than one level.

Whereas the above mandala represents the pure surroundings of a Buddha, this mandala represents the universe. This type of mandala is used for the mandala-offerings, during which one symbolically offers the universe to the Buddhas or to one's teacher.

Within Vajrayana practice, 100,000 of these mandala offerings (to create merit) can be part of the preliminary practices before a student even begins actual tantric practices. This mandala is generally structured according to the model of the universe as taught in a Buddhist classic text the Abhidharma-ko?a, with Mount Meru at the centre, surrounded by the continents, oceans and mountains, etc.

Visualization; When the focus of a meditation is an image, the meditation becomes visualization. Visualization is a specific kind of meditation. Visualization is sometimes called mental imagery or mental rehearsal.

It can take the form of a visual or kinesthetic view. If you are using a kinesthetic focus, you create in your mind the experience of doing something.

You might feel the sensations in your body. You might experience the action and its consequences in great detail in your mind.

If you are performing a simple visualization, you picture a setting, another person or a sequence of events -- something outside yourself. Visualization can be both visual and kinesthetic.

You can visualize yourself in a setting, experiencing the impact of that setting on your body and mind.

It’s no secret that visualization can be a powerful tool.

In order to understand the various levels and usages of visualization, first we need to throw the word visualization out of the window.

It is the wrong word because the word visualization implies something visual. In other words, it implies working with visual images and it also implies working with our eyes. This is incorrect. Instead, we are working with the imagination.

When we work with the imagination we’re not only working with imagined sights, but also with imagined sounds, smells, physical sensations, feelings – emotional feelings – and so on.

Obviously, we do that with our minds, not with our eyes.

If we think of the Western psychological division of the brain into a right side and a left side, Tibetan Buddhism develops both sides – both the intellectual, rational side and the side of creative imagination.

Therefore, when we speak of visualization in Buddhism, we’re not talking about some magical process. We’re talking about something quite practical, in terms of how to develop and use all our potentials, because we have potentials on both the right and left sides of the brain.

When we work with the imagination, we’re dealing with creativity, artistic aspects and so on. Alexander Berzin

Visualization Methods in Sutra

Everyone has experienced some kind of visualization in their lives. Professional athletes are known for using visualization to get ‘in the zone’ before a game.

Basically, they are trying to see the action before it happens so they will be better prepared and confident once out on the field.

In much the same way, visualization can be useful to you in your daily life by preparing you for a variety of upcoming situations.

The following four techniques are proven to be effective in promoting successful visualization.

- Treasure Map Technique.

This is a visualization technique that uses a physical component as well as the obvious mental component. To try this technique, you first need to think of something you would like to visualize – for example, getting a top score on an upcoming exam.

Start by drawing physical representations of all of the factors involved. You can draw yourself, a book to represent study, and maybe a building to represent the school.

Make the drawings a detailed as possible. The important factor isn’t the drawings themselves, but what you are picturing as you draw them. Your mind will be visualizing the road to success the whole time you are drawing out your map.

Be patient with this technique, as it will take time to become absorbed into the exercise. It will help to be in a quiet place, and turn off any distractions like a television or radio.

- Receptive Visualization.

Think of this technique as watching a movie in your head, only you control the scenes. This is a more passive approach than the previous one, but can be just as effective.

Again, it helps to be in a quiet place with no outside distractions. Lie back, close your eyes, and try to picture vividly the scene you want to visualize.

After you get a clear image in your head, start to add people and noises to the ‘movie’. Slowly build the image until you have a whole picture of the scene and can really feel yourself being involved in the action.

- Altered Memory Visualization. This technique is focused on changing past memories to have a more positive outcome. This is especially useful for resolving memories that involved anger or resentment.

Replay the scene in your mind, only replace the angry responses with more calm and controlled ones. It will take time to recreate the scene, but commit to doing this several times over.

After a while, your brain will only remember the scene playing out as you have re-created it, and the uncomfortable memories of the actual event will fade away.

- Meditate.

Using meditation is a great form of passive visualization that can have powerful results. As opposed to the other techniques, visualization through meditation is more of a byproduct than the main focus.

When you start meditating on a regular basis, you gain access to your inner self more than you have ever before. From that inner place is where you can start to experience strong visualizations.

To start, make a plan of setting aside time each day to meditate. You will get better and better at your meditation as you gain experience, so don’t be discouraged if you don’t have strong visualizations right away.

The idea with meditating is to completely empty the brain and allow it to go wherever it wants. You are not actively forcing any thoughts or images into your head. Start by focusing on breathing, and let your mind do whatever it wants to do naturally.

With this technique, you will start to have strong visualizations just by ‘letting go’ and allowing your brain to put on the show.

These visualizations are a great insight into your mind because they are not constructed manually; rather they just occur on their own merit.

The use of imagination in tantra is a very sophisticated topic, so I’d like to present it in a fairly sophisticated way. Let’s start on a general level. In tantra, we use our imaginations to imagine various Buddha-figures, yidam (yi-dam) in Tibetan.

These Buddha-figures are sometimes referred to as “deities,” although the Tibetan term being translated here, lhag-pay lha (lhag-pa’i lha), actually means “higher deities.” They are higher in the sense that they are not samsaric gods in a samsaric god-realm, but are beyond the uncontrollably recurring rebirth of limited beings.

all these figures represent the full enlightenment of a Buddha and each of them also represents prominently a particular aspect of Buddhahood, like Chenrezig or Avalokiteshvara embodying compassion and Manjushri embodying discriminating awareness or wisdom.

When we work with these Buddha-figures, we either imagine them in front of us or on top of our heads or, more frequently, we imagine ourselves in the form of one of them.

In order to be able to visualize a Buddha-figure, of course we have to know what that figure looks like. But visualization of ourselves in some special form is not as difficult as we might think.

Many Kamma??h?na (working places, or themes of meditation/reflection/visualisation), which are taught by the Buddha, are actually visualisations in regard of signs.

the 10 kasinas (certain colors, elements (as less distructing for the mind)

tenkind of corpse

(parts of) the body (k?ya) (as to gain disenchantment in regard of form)

Especially objects in signs have the purpose to concentrate the mind. In regard of the objects of repulsion, they also give ground for transcendent form by focusing on it.

The other objects are visualisations of virtues (of the Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha) or reflections on own virtues (generosity, conduct, virtues like Devas) and then there are certain other visualisations of thoughts to more directly "change" ones level of awarness.

All, how ever, are used to gain certain concentrations used on one hand as proper dwellings, livelihood for the mind on one hand and as object of investigation for insight.

Since the prerequisite to gain absorbed concentration is the (a good amount) abounding from sensuality, such as visualization of grave stimulating objects of form, beautifullness in form, form to identify one self with it or even such as "bodily sequences" are not found in the advices of the Buddha, with is also clear when remembering that to transcendent form is the very first step.

Where ever such kinds of meditations are found,they can be content regarded as "this is not the teaching of the Buddha".

It's pupose might be what ever kind of "illusion" one might objecting with it or what ever identification one tries to pursue with such, but certainly not for release, undinging, Nibbana. It might be also of use for wordily special powers.

Again, if reflecting on Deities and Devas, one is encouraged to remember virtues one has (means there must be experians to be able to visualise) equal them.

Form and material qualities are not regarded as graspworthy at all but obstacles for any useful one-pointness or for inside, aside of those giving disgust to it.

A person, having grasped after seeing the Buddha in Form, when finally met him was taught clearly that seeking after form makes no sense, not lasting as it is: "Who ever sees the Dhamma, sees the Tathagata, who ever sees the Tathagata, sees the Dhamma." It should be clear, that this does not put into hope that lasting, real Form can be found or worthy to seek after.

Visualization utilizes the right hemisphere of the brain that encodes information in images far more efficiently than the left hemisphere that is verbal/linguistic/logical/rational.

The old adage is that "a picture is worth a thousand words." This principle is the basis of the medieval system of memory training (see Francis Yates, The Art of Memory).

The unconscious expresses archetypal information using visual images and prelinguistic symbols that are psychologically powerful and empowering, as evidenced by the research of psychologist Carl Gustav Jung for example.

Virtually all religions and spiritual paths testify to powerful visionary experiences including in the Pali Canon, including collective visionary experiences. It seems to be psychologically innate. Poetry and art also testify to the power and importance of the visionary/symbolic dimension of consciousness.

I would say that as a general mechanism, whether Buddhist visualization or some other kind, it probably relies on the concept of neural plasticity. Visualization could be viewed as an exercise for the brain, which in turn affected the mind.

Essentially, we are what we think, within limits of what is possible of course.

Scientifically there are many examples of the brain being physically changed by the input it receives. This has been shown in musicians for example and the representation in their primary somatosensory cortices.

The increased representation is indicative of a greater abundance of receptors in the periphery and the combination confers better acuity, for example. Thus, the brain is sculpted by input, which in turn influences who we are or at the very least what we can do.

Now consider that mentally imagining an image or sound activates the same (or very similar) network of cells as perceiving the object for real. The implication is that our brains are also shaped by what we imagine, probably assuming you can imagine clearly.

Finally, perception, particularly when profound, has effects on the brain and body. Perhaps changing cardiorespiratory patterns, hormone release and all sorts of things.

Presumably, if you could imagine the same percept very clearly, and sustained, it would lead to the same set of physiological changes.

So, filling the mind with compassion, generating the experiential feeling associated with compassion should cause changes in the body that reflect genuine compassion, with the added bonus of the circuits being reinforced and easier to enter the next time.

Tibetan Buddhist meditation, in the form of tantric practice is a profound approach to the complete transformation and liberation of our body, speech and mind from what limits and obscures their natural potential. Often it is considered that the visualisation of colourful and inspiring deities – or ‘spiritual archetypes’ – is central to this way of practice.

This is partly true but tantric practice is so much more when we fully understand how it ‘works’. Tantra becomes a way of integrating many different aspects of our life into a radical process of awakening.

Our mind, our emotional and psychological life, our creative life, our body and relationships are all aspects of this process.

All that we are is included within this path of alchemical transformation. In this module series we will develop and deepen the practices that were also introduced in the Tasting the Essence of Tantra series.

In this series we go into more depth, detail and subtleties of these practices. This will include the practice of Mahamudra mediation on the nature of mind, the use of deity practice, energy work and the bridge between psychology and spirituality. Throughout there will be an emphasis on how meditation within the tantric tradition can approach our psychological and psycho-physical healing and transformation.

Tantra as western construction

Robert Brown notes that the term tantrism is a construction of western scholarship, not a concept that comes from the religious system itself. T?ntrikas (practitioners of Tantra) never attempted to define Tantra as a whole the way Western scholars have. Rather, the Tantric dimension of each South Asian religion had its own name:

Tantric Shaivism was known to its practitioners as the Mantramarga,

Tantric Buddhism has the indigenous name of the Vajrayana,

Tantric Vaishnavism was known as the Pañcaratra.