A 'Dzogchen Approach to Yoga The View of Dzogchen

In the Tibetan tradition, Dzogchen means the understanding of the total completeness, the primordial wholeness of a person. According to this perspective, this wholeness is present right from the very beginning of the path, from wherever we make a start. At first, this wholeness, this completeness, sounds very abstract and philosophical, as either a high-sounding platitude or the product of some long, complex process. A key to unlocking this seeming paradox, that the goal is present in the beginning, is to look directly to our experience in order to recognize that some kind of motivation already exists. From the point of view of Dzogchen, the whole teaching—its basis, path, and goal—can be understood by looking into our motivation.

The Importance of Motivation

All the Buddhist schools talk in some way at the beginning of the path about the importance of motivation, bodhicitta. The Mahayana tradition, for example, emphasizes the motivation to attain enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings. In that case, motivation is a basis for setting out on the path. But Dzogchen is said to be a direct rather than a gradual path; thus motivation is not the starting point for doing something else. The starting point is not separate from the path and the goal.

What do we mean then by motivation in Dzogchen? Motivation, bodhicitta, is just another name for Dzogchen, the total completeness of one’s being, present right now. More precisely, “motivation” here refers to that aspect of one’s complete being, which is its ability to know itself. It refers to the pure fact of being aware, our capacity and desire to know. The goal of our capacity and desire to know is nothing other than this awareness itself. Knowing wants to know. We experience this basic knowing as a desire to understand our world and ourselves. Motivation is always already there, working, shedding light, making conscious, mirroring the whole universe, overcoming boundaries to the unknown. Its intention is to know, and the practice of Dzogchen is to experience and be this knowing.

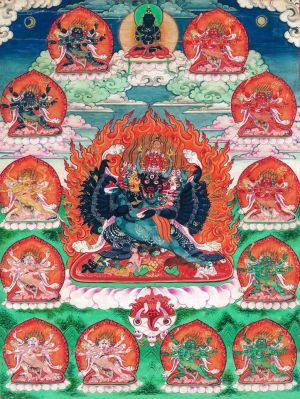

This motivation, this desire to know, goes beyond mere curiosity. It is wholeness desiring to know, to mirror itself. Dzogchen is known in Tibet as the summit of all paths, a teaching directly from the mind of the primordial buddha, Samantabhadra. But this does not mean, as I have said, that it is not a practical path to buddhahood, nor that one cannot put into practice the perspective of Dzogchen right from the start of the path. It needs, however, to be transmitted in order to wake up or point out this primordial knowing in a person. In Dzogchen this is known as direct introduction.

This direct introduction is like seeing all of one’s being in a mirror and understanding that one’s own awareness is that mirror. It is with this experience that the way of Dzogchen begins. But such a perspective is extremely difficult for our limited ego-structure to assimilate. It clashes with our self-image; it is too radical. We want to fit it back into our habitual perspective, to relegate it to the status of an experience, which easily becomes a memory that we can assimilate. It takes hard work to really be that mirror, to overcome that tremendous gulf of reified duality that prevents us from being it. We identify with too much of what the mirror reveals: all that we cannot accept and cannot understand in ourselves. We cannot be whole and overcome that split in ourselves that creates the observer who judges, who struggles, who strategizes, who defends, who needs such a self-image. Thus we can never truly relax and open up an awareness that is truly free to let everything be experienced, and to create out of that pure knowingness, bodhicitta.

What I am saying is that this knowingness, which is revealed in the direct introduction of Dzogchen and likened to a mirror, also reveals the obstacles to its full realization. In this sense, the knowledge revealed in direct introduction also provides the basis for overcoming obstacles in its very desire to know. Another way to put this would be to say that the experience of direct introduction provides us with a unique perspective and way of working with our situation. Thus it provides us with something related to (but ultimately more than) the desire to know that is involved in psychotherapy. We have at least a glimpse of a radically new perspective from which to observe ourselves. The methods of Dzogchen also provide us with a means to nurture this new perspective itself.

My primary teacher of Dzogchen, Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche, always said, “Observe yourself to discover how you are limited and conditioned, trapped in the cage of dualism like a little bird.” What this means is that we need to see that all our obstacles have reified dualism as their root, that this is our fundamental limitation.

This is not our usual understanding of our problems or of our positive qualities. Usually we take up the position of somebody who is getting better or worse, who is OK or not so good, who wants to be better or does not give a damn, and so on.

Every path has its characteristic perspective. Without understanding this perspective you cannot put it into practice, which is meditation. That is how the path progresses, as one unfolds the dialectical dance between the perspective and its application in practice. For example, if one understands vipassana meditation as the cultivation of mindfulness, observing, noting, and letting go of experiences, this is only a preparation. It is cultivating mindfulness for the purpose of inner calm, shamatha, which is a very useful skill, but it is not the true meaning of vipassana, which is insight into the nature of reality. To practice vipassana, one has to understand the perspective one is implementing, which is explained in different ways in various Buddhist schools.

Dzogchen too has its perspective, but with Dzogchen we are not looking at our limitations as something we need to do something to or with, to analyze or overcome, or transform or transmute. Why? Because the nature of primordial knowing is such that by knowing something in this way, you are already beyond reified dualism. To truly know one’s obstacles is to no longer have obstacles. This kind of knowing initiates a very powerful yet subtle dialectic in one’s experience. At the very beginning of the Dzogchen path, one can begin to learn that the perspective and its practice are actually not separate, and that the motivation of our basic knowingness and its obstacles are really not separate either. This is what gives this path its uniqueness. Once we are introduced to this primordial knowing that serves as our basic motivation, we can begin to look further into both what it is and what our obstacles are.

For example, there is a Dzogchen approach to the practices of calming the mind, {hint (Sanskrit: shamatha)* and insight, lagtong (Sanskrit: vipassana). This approach is found in the Nature of Mind Series (semde) of teachings. The introduction to this fundamental knowingness is very precise in the semde; one could say that it happens gradually. The reason that it is so precise is that it works step-by-step with the process of getting to know some fundamental aspects of our mind. It sets up a definite strategy about how we can come to experience ourselves beyond reified dualism. In this case then we must first know what this dualism is. In the semde one learns about it in two ways. The first is by direct confrontation through the power of the teacher’s introduction and/or through exercises one does oneself. The second is by thorough familiarization through trying to control one’s mind according to the traditional practices of calm and insight.

In the Dzogchen semde* one does not practice calm and insight for their own sake, as one does in other paths, but to reveal the inherent reification of subject and object in the effort of the mind to control and analyze itself. To practice them for their own sake means to progress gradually on the path by means of the experience and understanding these methods bring. To practice the nongradual path means to set about undercutting this inherent reification right from the start, but this does not mean one abandons all calm and insight. Rather, it means that one comes to recognize that these states are intrinsic aspects of our fundamental knowingness, and one does not have to strive after them. The subject, who strives to control the objects of his or her own experience through techniques of meditation, is a mental representation, an image. When one sees this, one can begin to relax into another level of experience in which the object of meditation loses its power to disturb or distract.

We can apply the same approach to yogic practice. In the Tibetan tantric tradition there are yogic practices such as Yantra Yoga, involving movements and postures, breathing exercises, and visualizations. From a practical standpoint, what is the Dzogchen approach to these practices? If Dzogchen works with what is, in the sense of not struggling to change anything, and yogic practices require discipline and overcoming resistances to regular practice, how can we avoid struggle?

In the Dzogchen view, these resistances, whether they are laziness, perfectionism, chronic health complaints, and so on, are to be respected. In this sense, this way of working has some similarities to the psychotherapeutic understanding of resistances. The resistances are intelligent; they cannot be bullied out of the way by a sovereign ego.

What is the root cause of these resistances? Ignoring and not working with what is. In this case, “what is” means the reality that my body is not just an object, even if I treat it well with gpod yogic exercises and breathing practices. This reality includes the fact that our body has an unconscious meaning for us and that this meaning needs to be addressed.

How is this meaning addressed in traditional practices? I am not saying here that this is a cultural issue, or that these yogic practices need to be understood in the context of the culture in which they were developed (although that may indeed be useful). Rather, in the traditional context, questions of body image, body ego, the relation of mind and body, and so on, were addressed in terms of the esoteric meditations on the vajra qt “energy body,” with its channels and chakras.

Now, the practices of the energy body are not beginning practices of this yoga; they can only really be done (that is, not just as visualizations) after one has mastered the method of held breath known as kumbhaka (Sanskrit), or “vase breathing.” I low can one dissolve this difficulty, in which questions of meaning arc present from the start, but only seemingly addressed at an advanced level of practice? The solution is to realize first that the esoteric meditations on the energy body are actually the heart of this yoga and can therefore be placed at the beginning; and second, that these meditations can be understood to deal with the psychological issues of the unconscious meanings of the body mentioned above.

To repeat: Dzogchen, the way of self-liberation, is a nongrad-ual path. This means that its principle, the understanding of the reality of self-liberation, can be applied right from the start of the path. Dzogchen, “wholeness,” “completeness,” means that understanding what is, in any moment or situation, is liberating. In Dzogchen this “what is” is explained in terms of essence, nature, and energy.’ So whether one is a beginner or not, the outlook, the practice, and the way of taking the practice out into the world, are the same: to know and experience the essence-nature-energy of one’s situation. This is to maintain beginner’s mind. The essence of this beginner’s mind is emptiness, its nature is clarity, and its energy is unceasing nondual manifestation.

We can approach tantric yoga practices from the standpoint of the gradual path: first you do this, then you do that. In fact, it seems absolutely necessary, because there is no way to nongradu-ally do practices such as vase breathing or advanced asanas such as the wheel and the peacock. This is true; one proceeds further and further into the yogic methods in stages. The key word here is “methods.” Relatively speaking, yoga works gradually on harmonizing the relationship between body, energy, and mind. Through movement and asanas, one controls breathing and thus motility; through control of motility, one can control the mind; through controlling the mind, one can in turn influence motility.

But there are still the questions: What is the Dzogchen of our body-mind? What is the nature of its actual wholeness, unity, and integrity? The key point is to understand that the symbolism of the energy body, especially the central channel, is a way to begin to experience our embodied being as essence-nature-energy. The essence of embodied being is empty, or as I prefer to translate it, an open dimension, like space. The nature of embodied being is clarity, radiant transparency, like light. The energy of embodied being is the harmonious unity of the polarity of the male and female aspects of energy.

How can we begin to get an inkling or a taste of what this is about? Through “visualizing” the central channel, whose symbolism encodes the reality to which it refers. I put “visualizing” in quotes to indicate that visualization is not so much looking at something mentally as having a felt sense of the meaning that a symbol,2 such as a white letter A or ayidam, presents. The central channel is the cosmic tree, the ridgepole of the universe, the tai chi, the singularity at the origin of all things, which is everywhere and nowhere. Our body is empty like space, but it is not a mere vacuity; it also has all its radiant energies; and its tensions are manifestations of harmonious balancing.

Another way to put this would be: the essence of body and mind are the same because both are like space; the nature of body and mind are the same because both are radiant like light; and the energy of body and mind are the same because both are the harmonious play of the male-female polarity. So to find the unity or connection between body and mind, one must work with the “visualization,” that is, the embodiment of the central channel. In this way tantric yoga is about discovering and living the unity of body-mind. It is also about discovering fundamental healing, as well as learning about, in relation to the primordial field of bodymind unity, the ways in which one’s habitual energy-field and deeply unconscious body image are distorted. Some connections to this way of looking at yoga are offered by Jungian psychology, as well as alternative approaches to bodywork such as those offered by Arthur Mindell and Julie Henderson?

So it is important to try and convey this perspective from the start. One can actually begin with the training in the central-channel practice, which usually forms part of more advanced breathing practices? In this way one can make the goal the path. According to individual circumstances, one can work with the movements and breathing techniques of yoga, so one can physically do the esoteric breathing practices that accompany visualization practices of channels and chakras.

In this process one can actually begin to unify scattered energy, technically known as karmic motility, which moves in the right left, lunar-solar, male-female channels, into the central channel. This unification of energy in the central channel brings about an experience of light that dissolves the mental representation that we have of our body-mind as an object of attachment and manipulation. The quality of this experience depends on which of the chakras is the focus of the unification. This embodiment of the unification of energy in the central channel is the heart of tantric yoga. And the experienced meaning of the central channel is nothing other than Dzogchen, the heart and soul of beginner’s mind/ body.

Channels and chakras arc not organs or structures found in our anatomical bodies. They are not objects, but ways that we can experience the world through our body. There is a specific Dzogchen approach to the tantric practices that involves the channels and chakras. The key point is to understand that the symbolism of the energy body, especially the central channel, is a way to begin to experience our embodied being as Dzogchen, the presence of total completeness. This total completeness has its essence, nature, and energy. The essence is empty, an open dimension, like space, and we can experience our body as this essence. The nature is clarity, radiant transparency like light, and we can experience our body as this radiance. The energy is unification, the polarity of the male and female aspects of embodied energy, and we can experience our body as this unification. If we have this ever-present goal in mind from the start of our practice of yoga, we will not get lost in technique or be discouraged by practical difficulties.

How can the Dzogchen approach to yoga that 1 have just outlined be applied more specifically to tantric, sexual yoga? As The Fivefold Essential Instruction says (p. 28): “At the time of intercourse when passionate attachment and the concepts associated with it arise, this is experienced as the creative energy of pristine awareness. If one does not know this, it is just attachment. Transforming this into pristine awareness means that by working with passionate attachment itself, passionate attachment is purified.”

The key is to have present the experience of our body as the essence-nature-energy we have just spoken about, and apply it to sexual experience. If we deeply know that our body is an open dimension, like space, with porous boundaries, then there is no attachment to the body because we cannot grasp space. Rather we experience this spacious aspect of our body in a profoundly nonconceptual, inexpressible way (mitogpa). If we deeply know that our body is like radiant light, then there also is no attachment to the body, because we experience a brilliant clarity (salwa) by means of our body that is also ungraspable. If we deeply know that our body is like a field that unifies all dualities, then all sexual energies are unified in an experience of pure pleasure (dewa) that overwhelms the grasping mind.

More specifically, sexual experience concentrates energy in the genitalia, and while men and women are different in their patterns of sexual arousal, it is important for both to know how to unite the polarities of genitals and head, for it is especially this unification that generates pure pleasure. To this end, it is useful to know how to use yogic techniques and visualizations to either draw energy upward from the genitals, bring it down from the crown of the head, or let it pervade one’s whole body. In this way you can maintain the right state (for each person) of energetic tension.

Let me give an example of working with another emotion using the same approach. The energy of anger concentrates in the heart and like fire spreads upward out of control, leading to angry concepts and actions. The energy of anger is itself mirrorlike pristine awareness; that is, we are adverse to a person or situation because we have projected that which we have rejected in ourselves onto the object. The object then acts as an irritating mirror showing us what we don’t want to see in ourselves. If we directly experience this mirroring function itself, rather than just its effects as angry concepts and actions, then while we may feel the energy of anger, it is not projected and it doesn’t become a source of irritation. We can keep this mirrorlike energy/awareness in the heart and just as with sexual energy, let it spread throughout the whole body. To this end, it is useful to know how to use yogic techniques and visualizations to draw the fiery heart-energy downward toward the navel so it does not get out of control. If we can hold the energy down in this way, perhaps with the aid of the seed syllable for fire, RAM, at the navel, as well as holding the breath through the kumbhaka technique, we can then spread this fire to the whole body. In this way, the angry concepts generated by the rising fire of anger will subside into the nonconceptual state of mirrorlike pristine awareness.

The Dzogchen approach to yoga emphasizes simplicity of method, but it can do this only by virtue of its unique view of ever-present wholeness and nonduality.