Against Empathy

by Glenn Wallis

The possibility of empathy is a western-buddhist dogma. Empathy, together with its near relative, compassion, may even be considered a necessary axiom of contemporary x-buddhist belief, whether in a secular, crypto, or traditional inflection. For, without the possibility of empathy and compassion, x-buddhism loses its ethical footing, its prime rationale for practice, and its very impetus toward the pro-social utopian. In this post, I’d like to present a paper that challenges the possibility of an activity that resembles our folk notions of “empathy.” The article, by the German thinker Jan Slaby, is aptly title “Against Empathy” (links below).

Before I do, I want to set the stage a bit by giving an indication of how these terms function in contemporary x-buddhist discourse. We can glean the axiomatic/dogmatic nature of the x-buddhist belief in empathy-compassion from the Tricycle article entitled “Empathy or Compassion? Reflections on the Compassion Meditation Conference.” This article is a report on a now familiar scene, where, “scholars and researchers in psychology, psychiatry, and neuroscience congregated alongside His Holiness the Dalai Lama for,” in this case, Emory University’s 2010 conference on “compassion meditation.” The question at hand was not “what do we mean by ‘empathy’ and ‘compassion’?” The conference presupposed folk meanings for the terms; namely, that they refer to feeling or, as the report puts it, “resonating” with, another’s pain.

The issue at hand was thus how empathy and compassion might differ from and complement one another. Go-to x-buddhist compassion expert, Matthieu Ricard, “western monk, scientist, and author,” explained the importance of resolving this matter by:

considering how the experience of empathy without compassion would induce incredibly unpleasant, even crippling, states. The following day, Matthieu explained the testing of this hypothesis in the lab, where seasoned meditators were instructed to resonate with others’ suffering without generating compassion or performing cognitive reappraisal until the practice became utterly unbearable—and it did. When the meditators in the lab then generated compassion, their experience transformed completely. These meditators had trained extensively in generating compassion in the face of suffering almost immediately, but teasing apart empathy and compassion in the lab proved to be extremely illuminating.

Neuroscientist Richard Davidson then “presented findings suggesting that empathy and compassion correlate to differing neural states:”

He found that the circuits engaged by compassion training partially overlap with those activated during empathy, but differ in that they also involve the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, which he suggested might play a role in expressing and enacting aspiration. Such would accord with the Buddhist definition of compassion—the aspiration that others be free from suffering.

So, one conclusion of the conference was that:

Empathy that resonates with another’s painful condition causes the empathizer to experience that same suffering, which can easily overwhelm. Training in compassion can transform the same empathy that in itself is debilitating into a helpful force.

Of course, we learn nothing about what empathy and compassion are from any of this. We are merely offered a circular argument: when certain subjects “resonated” with others’ “suffering,” thereby experiencing the “same” suffering, certain things occurred in the area of their brains that “might” have something to do with something called “aspiration” to “resonate” with and eliminate another’s pain. The burning question of just what these people were actually doing as they “resonated” is left unasked. Obviously, the very metaphor of “resonance” prejudices our understanding. It already assumes a direct correspondence and interaction between two poles. But nothing in the research indicates that anything like that—interaction, much less resonance—was happening at all. So, what was happening? Were the subjects imagining some scenario? Were they triggering their own emotions via their imaginations? Were they accessing vague elements of memory? You will never get an answer, much less the question, from an x-buddhist, caught, as s/he is in the circular dharmic machine.

I mention this conference because it shows the dogma of empathy/compassion as it is put into play by some of the most influential figures in the world of contemporary x-buddhism as well as in that of science-meets-meditation. It also has, we can surmise, a trickle-down effect. We can see the same kind of dogmatic/axiomatic rhetoric equally at work at the most popular level of the discourse. The most recent links on the Secular Buddhist Facebook page, for instance, are:

“How to Train the Compassionate Brain.” A new study finds that training in compassion makes us more altruistic.

“Meditation Makes Us Act with Compassion.” A new study suggests mindfulness meditation can help us overcome the “bystander effect.”

(Which led me to:)

“Can meditation make you more empathic?” A program that focuses on compassion was found to boost a person’s ability to read the facial expressions of others as well as activate regions in the brain that help us be more empathic.

How can we slow the rate at which the “empathy” buddheme is spreading?

_______________________

In his article, “Against Empathy: Critical Theory and the Social Brain,” Jan Slaby, a professor of philosophy at the Free University in Berlin, poses just that question. How, he asks, might we:

crack the unholy alliance between shallow, popularized human science and the trendsetting discourses and practices in the corporate universe and affirmative mainstream culture? What can scientists and scholars do in order to not blindly and unwittingly drive further and publicly promote the trends here outlined? (27)

Slaby’s question is doubly apt for us. In dealing with contemporary x-buddhism, we are simultaneously dealing with both the “corporate universe” and “affirmative mainstream culture.” The former, because of the collusion between x-buddhism and consumerism; the latter, because of the lockstep adherence in x-buddhist communities to what Barbara Ehrenreich calls the “smile or die” imperative. Slaby calls this imperative “a pervasive regime of positive, conformist, domesticated affectivity” (26). He sees it operating in western culture as a whole. Of course, “a whole” presupposes discreet units. X-buddhism is such a unit: it absorbs the values of its culture, cursorily refashions them in its own image, and finally reintroduces the now mildly exoticized originals back into the culture. It should be useful to quote Slaby at length on the basic issue of the “smile or die imperative” operating in x-buddhism and the wider culture. It is, he says:

ubiquitous, placing an effective ban on the open expression of negative emotion. Instead of letting affectivity be a field of resonance for a wide range of human experiences, including those that reflect potentially problematic, pathological aspects of today’s conditions of living, a strict policy is imposed towards a thin range of mind-numbing positive emotions and ways of “positive thinking.” It is a mixture of optimism, cheerfulness, sympathetic politeness and composed self-possession which restricts and controls the range of affects on display in everyday life. Thereby, the potential for critique and resistance is drowned effectively already on the level of sentiment, interpersonal style and emotional conduct. A specific perniciousness lies in this tendency, as emotional dispositions, once sufficiently engrained, tend to become so profound that they freeze into a kind of second nature. This means not only that they are rarely called into question, but that even our capacity to question them is severely limited, because our emotional outlook will inevitable also come to shape the very standards we employ in our normative self-assessments. Our emotions shape what seems natural to us. Because of this, it will be increasingly hard for individuals to even see and appreciate the potential value of alternatives to the dominant affective regime. (26)

So, again, how can x-buddhists be encouraged to step away from this particular set of ideological blinders–at least long enough to consider whether they are such? Slaby suggests that “the first step has to be the creation of an awareness of the material and discursive constellation that” he hints at in “Against Empathy.”

I will highlight a few salient features of that “constellation” here.

It is important, Slably says, first of all to recognize that the rhetoric of the advent of the empathetic human is being celebrated across various disciples. He cites social and economic theorist Jeremy Rifkin, president of The Foundation On Economic Trends, as a particularly noteworthy example. In the 1970s Rifkin wrote books with titles like How to Commit Revolution American Style: Bicentennial Declaration and Common Sense II: The Case Against Corporate Tyranny. In 2010, we get, The Empathic Civilization: The Race to Global Consciousness In a World In Crisis, wherein he claims:

A radical new view of human nature is emerging in the biological and cognitive sciences…Recent discoveries in brain science and child development are forcing us to rethink the long-held belief that human beings are, by nature, aggressive, materialistic, utilitarian, and self interested. The dawning realization that we are a fundamentally empathic species has profound and far-reaching consequences for society. (1)

That Rifkin is proclaiming the virtues of empathy is particularly telling. It reveals the extent to which the rhetoric of empathy has become an accepted part of our thinking about global issues. More ominously, it signals a retreat into the same kinds of feel-good utopian platitudes that our contemporary x-buddhim so excels in: We may be poisoning the air, land, and water; we may be pitiful stooges to manipulative corporate masters; we may be headed for economic meltdown, but, relax!: empathy is a “fundamental” human trait, capable of trumping aggression and materialism! As Slaby puts it:

Jeremy Rifkin has offered many a diagnosis and many a cure for the problems of our times. Globalization, structural changes in wage labor, the biotech revolution, Europe as a new global power, the new capitalist regime of ‘access’, hydrogen as the solution to global warming…Recently, Rifkin has added empathy to the list of world-saving memes…Rifkin’s recent joining the empathy party is telling of a global trend: Empathy is en vogue – the hottest stone not yet fully turned in the universe of humanism. The core storyline is one that is heard all too often these days: Human nature is in the process of taking on a fundamentally new shape – thanks mostly to the brain sciences, developmental psychology, primatology and other bio-psychological sciences, a new core human nature rife with emotion, attachment, communication – but most of all: empathy – is currently being revealed. And surely, this is GREAT NEWS, because empathy, together with all those other pro-social traits now suddenly in the scientific spotlight, is such an immensely beneficial thing. How fortunate indeed that humanity, just in the midst of another gigantic global crisis, and while on the verge of destroying for good the ecosystem of this earth, stumbled on a so far undiscovered profound positive characteristic of itself. (3)

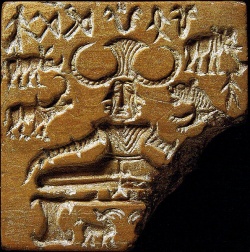

Given the saving role to be played by empathy in the coming age (think, for instance: the bodhisattva vow), it is unfortunate that we must interrupt the celebration and ask of the term: to what does it refer? Slaby’s next move is therefore to survey the literature for an answer. As with the x-buddhist usage of, for example, “mindfulness,” he concludes that the literature evinces a range of conceptual and theoretical models so broad as to render the term practically meaningless. “Empathy” ranges, namely, from low-level, automatic responses, such as emotional contagion and sympathetic concern, to the complex, high-level mentally deliberate process of perspective-taking. Note that the x-buddhist view of the empathy-compassion nexus intimated in the Tricycle report contains both automatic, low-level (“resonance”) and mental, high-level (“cognitive reappraisal”) dimensions.

Similar to scientists who employ “mindfulness” models in their research, to stay with our x-buddhist parallel, Slaby argues that in order to make progress in empathy research, we must first limit the current “terminological ambiguity and conflation” (7). He finds the definition of fellow philosopher Amy Coplan valuable toward that end.

[E]mpathy is a complex imaginative process in which an observer simulates another person’s situated psychological states while maintaining clear self-other differentiation. To say that empathy is “complex” is to say that it is simultaneously a cognitive and affective process. To say that empathy is “imaginative’ is to say that it involves the representation of a target’s states that are activated by, but not directly accessible through, the observer’s perception. And to say that empathy is a “simulation” is to say that the observer replicates or reconstructs the target’s experiences. (8)

As Slaby notes, this definition contains three basic components which, together, constitute a “fully fledged empathy” (8). Coplan’s account includes (i) both mentally deliberative and automatic traits, (ii) an other-person-oriented perspective, and, as that perspective requires, (iii) a perceived differentiation between oneself and another. Comparison to the Tricycle report shows agreement here. So does our common, folk understanding.

However, Slaby then proceeds to show how “all these components pose severe difficulties” (8). The most basic difficulties are not hard to predict. Just think about it. You may believe that you are feeling or “resonating” another’s pain, but on what grounds do you form this conclusion? What assumptions about shared experience, congruity of emotional response, common spontaneous reaction, and so much more, must be true for your claim of “empathy” to be coherent, much less demonstrable? Coplan summarizes the difficulties that she sees as follows:

[P]ersonal distress, false consensus effects, and general misunderstandings of the other are all associated with self-oriented perspective-taking. When we imagine ourselves in another person’s situation, it frequently results in inaccurate predictions and failed simulations of the other’s thoughts, feelings, and desires. It also makes us more likely to become emotionally over-aroused and, consequently, focused solely on our own experiences. (9)

If such a feeling/resonance-oriented version of empathy proves delusional, what about a perspective-shifting one? The folk version of perspective-shifting is captured in the trope of walking a mile in another’s shoes. Slaby cites Peter Goldie’s definition here:

Consciously and intentionally shifting your perspective in order to imagine being the other person, thereby sharing in his or her thoughts, feelings, decisions and other aspects of their psychology. (9)

Slaby elaborates on this definition. Perspective-shifting involves:

Accessing another’s mind from the inside—and thus only producing the same mental states in oneself as one assumes the other person to have, but shifting imaginatively into the other’s predicament while maintaining a clear-cut self/other differentiation. Only then, or so the expectation goes, might one succeed to feel what the other feels not from one’s own perspective but from the other’s. Only then will one “get at” what one wants to get at in one’s earnest attempts at understanding another person.” (9)

The only problem with this “quite demanding mental maneuver” is that it is impossible to achieve. What makes it so, according to Slaby, is that it requires nothing short of cancellation of human agency. Or, to cast it in a slightly different light, a view of empathy that presumes access to another’s experience can only be founded on an skewed theory of mind. Based on what we know of self-conscious agency, “the empathizer will ever only project and impose her own mental life, most notably her own agency, onto the other” (5). But, pace x-buddhists, Rifkin, and the New World Empathicos:

The fact that empathetic perspective shifting doesn’t work is not tragic. Rather, its failure is instructive, because in analyzing it we learn something about what it means to be a full-blooded agent, about what it means to possess a practical point of view. Understanding this failure provides us with a more adequate understanding of the mind and of personhood, and thus is in the end also informative for a better way to conceive of beneficial and praiseworthy ways of interpersonal interaction that actually do work. (10)

With a similarly absurd irony, x-buddhist views of empathy require usurpation of agency and objectification of the other person through an imagined, yet egoistically-informed, experiential correspondence. In fact, the prevailing x-buddhist view of empathy requires, yet again, an atomistic/atmanistic view of mind. Empathy is understood as an encounter between discrete minds. Yet, as Slaby argues, we may abandon that particular x-buddhist absurdity by insisting on a richer and more robust notion of agency, one that involves an overturning of the currently fashionable, and facile, theory of the “social brain.”

X-buddhist allies such as Daniel Golemen present an optimistic picture of personhood, one that involves “hard-wired” pro-social–emotionally attuned, communicative, and cooperative–qualities. Slaby offers another possibility, which he calls, following anthropologist Allan Young, “Human Nature 1.0.” Unlike Goleman’s and Rifkin’s domesticated, conformist, and thus disempowering, Human Nature 2.0, this involves a view of agency that allows the person to, among other things, “sidestep the logic of market and commodity capitalism and the rigorous framing of life choices that it engenders.”