Difference between revisions of "Amoghavajra and Chinese Esoteric Buddhism"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:H2_21.76.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:H2_21.76.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

A review of {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Esoteric Buddhism]]: [[Amoghavajra]] and the Ruling {{Wiki|Elite}}, by Geoffrey C. Goble. | A review of {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Esoteric Buddhism]]: [[Amoghavajra]] and the Ruling {{Wiki|Elite}}, by Geoffrey C. Goble. | ||

[[File:Breath-o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Breath-o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

[[Scholars]] of [[Chinese Buddhism]] have often [[recognized]] [[Śubhākarasiṃha]] (637 – 735), [[Vajrabodhi]] (671 – 741) and [[Amoghavajra]] (704 – 774) collectively as the most important pioneers of [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhism in China]]. In this well-structured {{Wiki|dissertation}}, Geoffrey Goble argues that [[Amoghavajra]] alone, while already [[recognized]] as the most influential of the three, should deserve credit as the {{Wiki|real}} founder. As a result of rare Tang court {{Wiki|patronage}} of [[Buddhism]], [[Amoghavajra]] sustained a [[lineage]] of teachings and practices institutionally. Through detailed [[analysis]], Goble unveils the [[reasons]] that led to the personal and institutional [[success]] of this non-Chinese [[Monk]] among the ruling {{Wiki|elite}} in the second half of the eighth century. Goble fills this {{Wiki|dissertation}} with [[insights]] on the interplay of [[religion]] and {{Wiki|politics}} in the {{Wiki|Tang dynasty}} by examining how [[Amoghavajra]] wielded [[influence]] on contemporary and subsequent [[development]] of [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhism in China]]. | [[Scholars]] of [[Chinese Buddhism]] have often [[recognized]] [[Śubhākarasiṃha]] (637 – 735), [[Vajrabodhi]] (671 – 741) and [[Amoghavajra]] (704 – 774) collectively as the most important pioneers of [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhism in China]]. In this well-structured {{Wiki|dissertation}}, Geoffrey Goble argues that [[Amoghavajra]] alone, while already [[recognized]] as the most influential of the three, should deserve credit as the {{Wiki|real}} founder. As a result of rare Tang court {{Wiki|patronage}} of [[Buddhism]], [[Amoghavajra]] sustained a [[lineage]] of teachings and practices institutionally. Through detailed [[analysis]], Goble unveils the [[reasons]] that led to the personal and institutional [[success]] of this non-Chinese [[Monk]] among the ruling {{Wiki|elite}} in the second half of the eighth century. Goble fills this {{Wiki|dissertation}} with [[insights]] on the interplay of [[religion]] and {{Wiki|politics}} in the {{Wiki|Tang dynasty}} by examining how [[Amoghavajra]] wielded [[influence]] on contemporary and subsequent [[development]] of [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhism in China]]. | ||

[[File:Buddblotus.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Buddblotus.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Goble defines {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Esoteric Buddhism]] (also known as [[zhenyan]] or mijiao) as a variety of [[Buddhism]] that became identifiable from the 750s in Tang [[China]]. It employs [[maṇḍalas]], [[mantras]], [[mudrās]], and [[meditative]] [[visualizations]] for {{Wiki|soteriological}} and {{Wiki|practical}} purposes (pp. 1). Goble begins his {{Wiki|dissertation}} presenting an invaluable review of seminal {{Wiki|scholarship}} from [[China]], [[Japan]] and the {{Wiki|west}}. As part of an ongoing [[investigation]] into the founding of [[tantric]] practices in [[China]], this {{Wiki|dissertation}} refutes some common assumptions as well as raises some broader issues regarding the interaction of [[religion]] and state in Tang [[China]]. In [[Chapter]] One, the author presents several refutations of current research. His most significant [[assertion]] is that concerning [[Amoghavajra]]’s {{Wiki|status}} as the founder of [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhism in China]] (pp. 65). Although the latest of the three [[monks]] commonly associated with early [[Esoteric Buddhism]], [[Amoghavajra]] translated the greatest number of texts, was the first to be bestowed Tang {{Wiki|imperial}} titles during his [[lifetime]], and was the first to transmit the complete [[Diamond]] Pinnacle [[Scripture]] (an authoritative text that established {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Esoteric Buddhism]]) to [[China]]. Goble’s detailed and convincing presentation of {{Wiki|evidence}} from {{Wiki|biographies}} and [[Amoghavajra]]’s own words substantiates this claim. | + | Goble defines {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Esoteric Buddhism]] (also known as [[zhenyan]] or mijiao) as a variety of [[Buddhism]] that became identifiable from the 750s in Tang [[China]]. It employs [[maṇḍalas]], [[mantras]], [[mudrās]], and [[meditative]] [[visualizations]] for {{Wiki|soteriological}} and {{Wiki|practical}} purposes (pp. 1). Goble begins his {{Wiki|dissertation}} presenting an invaluable review of seminal {{Wiki|scholarship}} from [[China]], [[Japan]] and the {{Wiki|west}}. As part of an ongoing [[investigation]] into the founding of [[tantric]] practices in [[China]], this {{Wiki|dissertation}} refutes some common {{Wiki|assumptions}} as well as raises some broader issues regarding the interaction of [[religion]] and [[state]] in Tang [[China]]. In [[Chapter]] One, the author presents several refutations of current research. His most significant [[assertion]] is that concerning [[Amoghavajra]]’s {{Wiki|status}} as the founder of [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhism in China]] (pp. 65). Although the latest of the three [[monks]] commonly associated with early [[Esoteric Buddhism]], [[Amoghavajra]] translated the greatest number of texts, was the first to be bestowed Tang {{Wiki|imperial}} titles during his [[lifetime]], and was the first to transmit the complete [[Diamond]] Pinnacle [[Scripture]] (an authoritative text that established {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Esoteric Buddhism]]) to [[China]]. Goble’s detailed and convincing presentation of {{Wiki|evidence}} from {{Wiki|biographies}} and [[Amoghavajra]]’s [[own]] words substantiates this claim. |

| − | [[Chapter]] Two presents invaluable {{Wiki|evidence}} relating to the [[reasons]] for court {{Wiki|patronage}} of [[Amoghavajra]] soon after the {{Wiki|An Lushan}} rebellion that started in 755. Instead of prevailing assumptions that [[Esoteric Buddhism]] became popular because it served in a state [[protection]] capacity and because the [[Indic]] [[elements]] were sinicized, Goble argues that the {{Wiki|real}} [[reason]] lies in the similarity between [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhist]] [[rituals]] and pre-existing Tang state [[rites]]. Goble sees little necessity for [[adaptation]] of the foreign [[rituals]] to make them comprehensible to the Tang court. [[Esoteric Buddhism]], like {{Wiki|Daoist}} [[rites]], supported the [[emperor]] for the dual purposes of {{Wiki|political}} stability and {{Wiki|imperial}} longevity (pp. 101). Their [[rites]] employed similar methods such as [[mental]] [[visualization]] techniques to recreate a [[supernatural]] [[realm]] of [[beings]] that listened to the adept’s wishes. Goble has effectively pointed out the similarities were coincidental rather than [[conscious]] adaptations that prior {{Wiki|scholarship}} assumed. In addition, [[Esoteric Buddhism]] appealed to the court in two special ways: comparative [[simplicity]] of [[Esoteric Buddhism]] to attain similar goals (pp. 127), and hence, the apparent technological advancement of these [[rites]]. | + | [[Chapter]] Two presents invaluable {{Wiki|evidence}} relating to the [[reasons]] for court {{Wiki|patronage}} of [[Amoghavajra]] soon after the {{Wiki|An Lushan}} rebellion that started in 755. Instead of prevailing {{Wiki|assumptions}} that [[Esoteric Buddhism]] became popular because it served in a [[state]] [[protection]] capacity and because the [[Indic]] [[elements]] were sinicized, Goble argues that the {{Wiki|real}} [[reason]] lies in the similarity between [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhist]] [[rituals]] and pre-existing [[Tang state]] [[rites]]. Goble sees little necessity for [[adaptation]] of the foreign [[rituals]] to make them comprehensible to the Tang court. [[Esoteric Buddhism]], like {{Wiki|Daoist}} [[rites]], supported the [[emperor]] for the dual purposes of {{Wiki|political}} stability and {{Wiki|imperial}} longevity (pp. 101). Their [[rites]] employed similar [[methods]] such as [[mental]] [[visualization]] [[techniques]] to recreate a [[supernatural]] [[realm]] of [[beings]] that listened to the adept’s wishes. Goble has effectively pointed out the similarities were coincidental rather than [[conscious]] adaptations that prior {{Wiki|scholarship}} assumed. In addition, [[Esoteric Buddhism]] appealed to the court in two special ways: comparative [[simplicity]] of [[Esoteric Buddhism]] to attain similar goals (pp. 127), and hence, the apparent technological advancement of these [[rites]]. |

| − | In [[Chapter]] Three, Goble identifies an even more significant [[difference]] between [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhist]] [[rituals]] and pre-existing Sinitic practices: the ability to kill enemies, something that indigenous [[rites]] could not do. [[Amoghavajra]] could have invoked the procedures of [[Acala]], the [[immovable]] [[wrathful]] [[king]] who destroys [[mental]] [[defilements]], to kill tens of thousands of rebels and so, to help the {{Wiki|imperial}} family quell the {{Wiki|An Lushan}} rebellion. Goble presents this advantageous ability for [[Buddhist]] [[powers]] to kill {{Wiki|individuals}} and [[demons]] en [[masse]] as a [[reason]] for quick adoption by the threatened Tang {{Wiki|imperial}} family during the period of {{Wiki|chaos}} from 755 to 765. | + | In [[Chapter]] Three, Goble identifies an even more significant [[difference]] between [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhist]] [[rituals]] and pre-existing Sinitic practices: the ability to kill enemies, something that indigenous [[rites]] could not do. [[Amoghavajra]] could have invoked the procedures of [[Acala]], the [[immovable]] [[wrathful]] [[king]] who destroys [[mental]] [[defilements]], to kill tens of thousands of rebels and so, to help the {{Wiki|imperial}} [[family]] quell the {{Wiki|An Lushan}} rebellion. Goble presents this advantageous ability for [[Buddhist]] [[powers]] to kill {{Wiki|individuals}} and [[demons]] en [[masse]] as a [[reason]] for quick adoption by the threatened Tang {{Wiki|imperial}} [[family]] during the period of {{Wiki|chaos}} from 755 to 765. |

[[File:Amoghavajra.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Amoghavajra.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Goble continues his [[interesting]] narration of [[Amoghavajra]]’s rise to [[Power]] in [[Chapter]] Four by discussing his personal relationship with the {{Wiki|elite}} surrounding the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[emperor]]. Goble presents [[Amoghavajra]]’s interactions with {{Wiki|imperial}} family members such as {{Wiki|Empress}} Zhang, {{Wiki|Empress}} Dugu, the Han {{Wiki|prince}}, and the Huayang {{Wiki|princess}} (pp. 178 – 183), as well as important court personnel including Geshu Han (pp. 185) and civil Grand Councilors (pp. 191). Goble astutely notes that the [[esoteric]] [[rites]] had {{Wiki|Central Asia}}n (probably [[wikipedia:Sogdiana|Sogdian]] or {{Wiki|Khotanese}}) origins and could have appealed to the {{Wiki|military}} and bureaucratic {{Wiki|elite}} such as Geshu Han, Li Baoyu and Du Hongjian (pp. 204) who had similar {{Wiki|ethnic}} origins. [[Amoghavajra]]’s [[success]] enabled [[Esoteric Buddhism]] to be instituted in [[China]], eventually resulting in the formalization of an office of the Commissioner of [[Merit]] and [[Virtue]]. | + | Goble continues his [[interesting]] narration of [[Amoghavajra]]’s rise to [[Power]] in [[Chapter]] Four by discussing his personal relationship with the {{Wiki|elite}} surrounding the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[emperor]]. Goble presents [[Amoghavajra]]’s interactions with {{Wiki|imperial}} [[family]] members such as {{Wiki|Empress}} Zhang, {{Wiki|Empress}} Dugu, the Han {{Wiki|prince}}, and the Huayang {{Wiki|princess}} (pp. 178 – 183), as well as important court personnel [[including]] Geshu Han (pp. 185) and civil Grand Councilors (pp. 191). Goble astutely notes that the [[esoteric]] [[rites]] had {{Wiki|Central Asia}}n (probably [[wikipedia:Sogdiana|Sogdian]] or {{Wiki|Khotanese}}) origins and could have appealed to the {{Wiki|military}} and bureaucratic {{Wiki|elite}} such as Geshu Han, Li Baoyu and Du Hongjian (pp. 204) who had similar {{Wiki|ethnic}} origins. [[Amoghavajra]]’s [[success]] enabled [[Esoteric Buddhism]] to be instituted in [[China]], eventually resulting in the formalization of an office of the Commissioner of [[Merit]] and [[Virtue]]. |

In Tang [[China]], [[Amoghavajra]] was a very important [[Buddhist monk]]: second only to [[Xuanzang]] in terms of imperially-sponsored textual production, building of [[monasteries]], and oversight of [[Buddhist]] [[monks]] (pp. 221). In [[Chapter]] Five, Goble identifies the critical textual, institutional, and lineal [[activities]] that helped [[Amoghavajra]] define the beginnings of [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhism in China]] under the pre-established [[Buddhist]] framework then (pp. 223). | In Tang [[China]], [[Amoghavajra]] was a very important [[Buddhist monk]]: second only to [[Xuanzang]] in terms of imperially-sponsored textual production, building of [[monasteries]], and oversight of [[Buddhist]] [[monks]] (pp. 221). In [[Chapter]] Five, Goble identifies the critical textual, institutional, and lineal [[activities]] that helped [[Amoghavajra]] define the beginnings of [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhism in China]] under the pre-established [[Buddhist]] framework then (pp. 223). | ||

| − | This {{Wiki|dissertation}} has made an invaluable contribution to the study of Tang [[Buddhism]]. Although [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhism in China]] is an under-studied topic, this piece of research has revealed that this type of [[Buddhism]] is indispensable to [[scholars]] of [[Buddhism]] and {{Wiki|politics}}. While Goble has not explicitly claimed it in the {{Wiki|dissertation}}, state support was obviously crucial to the massive [[propagation]] and institutionalization of a [[religion]] in {{Wiki|medieval}} [[China]]. Hence, such a detailed study of the intricate factors that contributed to the [[Power]] play at personal and institutional, [[ritualistic]] and {{Wiki|political}} levels helps to underscore the works of {{Wiki|eminent}} [[monks]]. Although centered chronologically on the [[personality]] of [[Amoghavajra]], this {{Wiki|dissertation}} is as much a study of the [[development]] of [[Buddhism in China]] as it is about an influential [[Buddhist monk]]. | + | This {{Wiki|dissertation}} has made an invaluable contribution to the study of Tang [[Buddhism]]. Although [[Esoteric]] [[Buddhism in China]] is an under-studied topic, this piece of research has revealed that this type of [[Buddhism]] is indispensable to [[scholars]] of [[Buddhism]] and {{Wiki|politics}}. While Goble has not explicitly claimed it in the {{Wiki|dissertation}}, [[state]] support was obviously crucial to the massive [[propagation]] and institutionalization of a [[religion]] in {{Wiki|medieval}} [[China]]. Hence, such a detailed study of the intricate factors that contributed to the [[Power]] play at personal and institutional, [[ritualistic]] and {{Wiki|political}} levels helps to underscore the works of {{Wiki|eminent}} [[monks]]. Although centered chronologically on the [[personality]] of [[Amoghavajra]], this {{Wiki|dissertation}} is as much a study of the [[development]] of [[Buddhism in China]] as it is about an influential [[Buddhist monk]]. |

[[File:I-Amoghavajra.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:I-Amoghavajra.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

'''[[Primary]] Sources''' | '''[[Primary]] Sources''' | ||

| − | :Du You 杜佑 and Wang Wenjin. Tong Dian 通典. 5 vols. {{Wiki|Beijing}}: Zhonghua shuju : Xinhua shudian {{Wiki|Beijing}} faxingsuo faxing, 1988. | + | :Du You 杜佑 and Wang Wenjin. Tong Dian 通典. 5 vols. {{Wiki|Beijing}}: Zhonghua shuju : [[Xinhua]] shudian {{Wiki|Beijing}} faxingsuo [[faxing]], 1988. |

| − | :[[Li Fang]] 李昉. [[Taiping]] Guang Ji 太平廣記. 10 vols. {{Wiki|Beijing}}: Zhonghua shuju : Xinhua shudian {{Wiki|Beijing}} faxingsuo faxing, 2003. | + | :[[Li Fang]] 李昉. [[Taiping]] Guang Ji 太平廣記. 10 vols. {{Wiki|Beijing}}: Zhonghua shuju : [[Xinhua]] shudian {{Wiki|Beijing}} faxingsuo [[faxing]], 2003. |

:Li Linfu 李林甫 and [[Chen]] Zhongfu 陳仲夫 eds. Tang Liudian 唐六典. {{Wiki|Beijing}}: Zhongguo shuju 中華書局, 1992. | :Li Linfu 李林甫 and [[Chen]] Zhongfu 陳仲夫 eds. Tang Liudian 唐六典. {{Wiki|Beijing}}: Zhongguo shuju 中華書局, 1992. | ||

| − | :Jiu Tang shu 舊唐書. 16 vols. {{Wiki|Beijing}}: Zhonghua shuju chuban faxing, 1975. Reprint, 2002. | + | :Jiu Tang shu 舊唐書. 16 vols. {{Wiki|Beijing}}: Zhonghua shuju chuban [[faxing]], 1975. Reprint, 2002. |

| − | :Xin Tang shu 新唐書. 20 vols. {{Wiki|Beijing}}: [[Zhong]] hua shuju chuban faxing, 1975. Reprint, 2002. | + | :Xin Tang shu 新唐書. 20 vols. {{Wiki|Beijing}}: [[Zhong]] hua shuju chuban [[faxing]], 1975. Reprint, 2002. |

'''{{Wiki|Dissertation}} [[Information]]''' | '''{{Wiki|Dissertation}} [[Information]]''' | ||

| − | Indiana {{Wiki|University}}. 2012. 315 pp. [[Primary]] Advisor: Aaron Stalnaker. | + | [[Indiana]] {{Wiki|University}}. 2012. 315 pp. [[Primary]] Advisor: Aaron Stalnaker. |

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

| − | Shi Jue Wei (Poh Yee Wong)<br/> | + | Shi Jue Wei (Poh Yee [[Wong]])<br/> |

Research Associate<br/> | Research Associate<br/> | ||

International [[Buddhist]] Progress {{Wiki|Society}}<br/> | International [[Buddhist]] Progress {{Wiki|Society}}<br/> | ||

Latest revision as of 15:59, 16 February 2024

A review of Chinese Esoteric Buddhism: Amoghavajra and the Ruling Elite, by Geoffrey C. Goble.

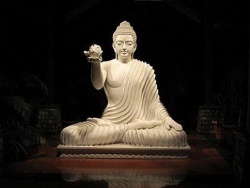

Scholars of Chinese Buddhism have often recognized Śubhākarasiṃha (637 – 735), Vajrabodhi (671 – 741) and Amoghavajra (704 – 774) collectively as the most important pioneers of Esoteric Buddhism in China. In this well-structured dissertation, Geoffrey Goble argues that Amoghavajra alone, while already recognized as the most influential of the three, should deserve credit as the real founder. As a result of rare Tang court patronage of Buddhism, Amoghavajra sustained a lineage of teachings and practices institutionally. Through detailed analysis, Goble unveils the reasons that led to the personal and institutional success of this non-Chinese Monk among the ruling elite in the second half of the eighth century. Goble fills this dissertation with insights on the interplay of religion and politics in the Tang dynasty by examining how Amoghavajra wielded influence on contemporary and subsequent development of Esoteric Buddhism in China.

Goble defines Chinese Esoteric Buddhism (also known as zhenyan or mijiao) as a variety of Buddhism that became identifiable from the 750s in Tang China. It employs maṇḍalas, mantras, mudrās, and meditative visualizations for soteriological and practical purposes (pp. 1). Goble begins his dissertation presenting an invaluable review of seminal scholarship from China, Japan and the west. As part of an ongoing investigation into the founding of tantric practices in China, this dissertation refutes some common assumptions as well as raises some broader issues regarding the interaction of religion and state in Tang China. In Chapter One, the author presents several refutations of current research. His most significant assertion is that concerning Amoghavajra’s status as the founder of Esoteric Buddhism in China (pp. 65). Although the latest of the three monks commonly associated with early Esoteric Buddhism, Amoghavajra translated the greatest number of texts, was the first to be bestowed Tang imperial titles during his lifetime, and was the first to transmit the complete Diamond Pinnacle Scripture (an authoritative text that established Chinese Esoteric Buddhism) to China. Goble’s detailed and convincing presentation of evidence from biographies and Amoghavajra’s own words substantiates this claim.

Chapter Two presents invaluable evidence relating to the reasons for court patronage of Amoghavajra soon after the An Lushan rebellion that started in 755. Instead of prevailing assumptions that Esoteric Buddhism became popular because it served in a state protection capacity and because the Indic elements were sinicized, Goble argues that the real reason lies in the similarity between Esoteric Buddhist rituals and pre-existing Tang state rites. Goble sees little necessity for adaptation of the foreign rituals to make them comprehensible to the Tang court. Esoteric Buddhism, like Daoist rites, supported the emperor for the dual purposes of political stability and imperial longevity (pp. 101). Their rites employed similar methods such as mental visualization techniques to recreate a supernatural realm of beings that listened to the adept’s wishes. Goble has effectively pointed out the similarities were coincidental rather than conscious adaptations that prior scholarship assumed. In addition, Esoteric Buddhism appealed to the court in two special ways: comparative simplicity of Esoteric Buddhism to attain similar goals (pp. 127), and hence, the apparent technological advancement of these rites.

In Chapter Three, Goble identifies an even more significant difference between Esoteric Buddhist rituals and pre-existing Sinitic practices: the ability to kill enemies, something that indigenous rites could not do. Amoghavajra could have invoked the procedures of Acala, the immovable wrathful king who destroys mental defilements, to kill tens of thousands of rebels and so, to help the imperial family quell the An Lushan rebellion. Goble presents this advantageous ability for Buddhist powers to kill individuals and demons en masse as a reason for quick adoption by the threatened Tang imperial family during the period of chaos from 755 to 765.

Goble continues his interesting narration of Amoghavajra’s rise to Power in Chapter Four by discussing his personal relationship with the elite surrounding the Chinese emperor. Goble presents Amoghavajra’s interactions with imperial family members such as Empress Zhang, Empress Dugu, the Han prince, and the Huayang princess (pp. 178 – 183), as well as important court personnel including Geshu Han (pp. 185) and civil Grand Councilors (pp. 191). Goble astutely notes that the esoteric rites had Central Asian (probably Sogdian or Khotanese) origins and could have appealed to the military and bureaucratic elite such as Geshu Han, Li Baoyu and Du Hongjian (pp. 204) who had similar ethnic origins. Amoghavajra’s success enabled Esoteric Buddhism to be instituted in China, eventually resulting in the formalization of an office of the Commissioner of Merit and Virtue.

In Tang China, Amoghavajra was a very important Buddhist monk: second only to Xuanzang in terms of imperially-sponsored textual production, building of monasteries, and oversight of Buddhist monks (pp. 221). In Chapter Five, Goble identifies the critical textual, institutional, and lineal activities that helped Amoghavajra define the beginnings of Esoteric Buddhism in China under the pre-established Buddhist framework then (pp. 223).

This dissertation has made an invaluable contribution to the study of Tang Buddhism. Although Esoteric Buddhism in China is an under-studied topic, this piece of research has revealed that this type of Buddhism is indispensable to scholars of Buddhism and politics. While Goble has not explicitly claimed it in the dissertation, state support was obviously crucial to the massive propagation and institutionalization of a religion in medieval China. Hence, such a detailed study of the intricate factors that contributed to the Power play at personal and institutional, ritualistic and political levels helps to underscore the works of eminent monks. Although centered chronologically on the personality of Amoghavajra, this dissertation is as much a study of the development of Buddhism in China as it is about an influential Buddhist monk.

Primary Sources

- Du You 杜佑 and Wang Wenjin. Tong Dian 通典. 5 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju : Xinhua shudian Beijing faxingsuo faxing, 1988.

- Li Fang 李昉. Taiping Guang Ji 太平廣記. 10 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju : Xinhua shudian Beijing faxingsuo faxing, 2003.

- Li Linfu 李林甫 and Chen Zhongfu 陳仲夫 eds. Tang Liudian 唐六典. Beijing: Zhongguo shuju 中華書局, 1992.

- Jiu Tang shu 舊唐書. 16 vols. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju chuban faxing, 1975. Reprint, 2002.

- Xin Tang shu 新唐書. 20 vols. Beijing: Zhong hua shuju chuban faxing, 1975. Reprint, 2002.

Indiana University. 2012. 315 pp. Primary Advisor: Aaron Stalnaker.

Source

Shi Jue Wei (Poh Yee Wong)

Research Associate

International Buddhist Progress Society

juewei@ibps.org

dissertationreviews.org