BUDDHISM IN MYANMAR

Shwe Bhone Point Pagoda in Myanmar

Almost 90 percent of the people in Myanmar are Buddhists, and the proportion is higher among the Burmese majority. Buddhism is followed by many of the non-Burmese ethnic groups. While all these groups follow Theravada Buddhism, there are some differences between the in beliefs and practices and those of the Burmese. Buddhist beliefs and practices include animistic elements that reflect belief systems predating the introduction of Buddhism. Among the Burmese, this includes the worship of nats, which maybe associated with houses, in individuals, and natural features.

Buddhism pervades every aspect of Burmese life and the religion perhaps has more of a hold on Myanmar than any nation in the world. Burma is filled with temples and monasteries and monks. Even the poorest villages maintain a temples and a community of monks. There is a proverb that states, "To be Burmese is to be Buddhist."

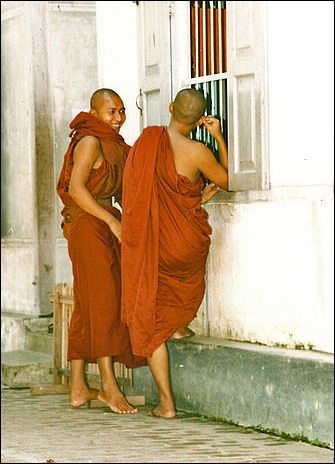

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “The golden spires and stupas of Buddhist temples soar above jungle, plains and urbanscapes. Red-robed monks—there are nearly 400,000 of them in Myanmar—are the most revered members of society. Pursuing lives of purity, austerity and self-discipline, they collect alms daily, forging a sacred religious bond with those who dispense charity. Nearly every Burmese adolescent boy dons robes and lives in a monastery for periods of between a few weeks and several years, practicing vipassana. As adults, Burmese return to the monastery to reconnect with Buddhist values and escape from daily pressures. And Buddhism has shaped the politics of Myanmar for generations. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian magazine, September 2012]

Buddhism is known to ordinary Burmese as “boda batha” , the way of Buddha. The distinction of Theravada Buddhism is something that is only known to educated Burmese. There were a few monks in history who could memorize the whole 30-volume set of texts by heart. According to the Guinness Book of Records, Bhandanta Vicittaba Vumsa (1911-93) recited 16,000 pages of Buddhist canonical texts in Tangon, Myanmar in May 1974. This feat is regarded as the world record for memorization. Buddhist texts are now available in digital format. The complete Buddhist texts published in book form is in about 30 volumes. Now it is in one single CD!

Manning Nash wrote in the Cultural Encyclopedia: “Burmese Buddhism is characterized by consensual elements of knowledge, belief and practice that are separate from more specialized knowledge...The ideas of “kan” (related to karma) and “kutho” (merit) underlie religious life.

Websites and Resources on Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Religious Tolerance Page religioustolerance.org/buddhism ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Tricycle: The Buddhist Review tricycle.org ; BBC - Religion: Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion ; Buddhist Centre thebuddhistcentre.com; A sketch of the Buddha's Life accesstoinsight.org ; What Was The Buddha Like? by Ven S. Dhammika buddhanet.net ; Jataka Tales (Stories About Buddha) sacred-texts.com ; Illustrated Jataka Tales and Buddhist stories ignca.nic.in/jatak ; Buddhist Tales buddhanet.net ; Arahants, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas by Bhikkhu Bodhi accesstoinsight.org ; Victoria and Albert Museum vam.ac.uk/collections/asia/asia_features/buddhism/index ;

Theravada Buddhism: Readings in Theravada Buddhism, Access to Insight accesstoinsight.org/ ; Readings in Buddhism, Vipassana Research Institute (English, Southeast Asian and Indian Languages) tipitaka.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ; Pali Canon Online palicanon.org ; Vipassanā (Theravada Buddhist Meditation) Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Pali Canon - Access to Insight accesstoinsight.org ; Forest monk tradition abhayagiri.org/about/thai-forest-tradition ; BBC Theravada Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion

Theravada Buddhism

relic of the Buddha from the Supreme Patriarch of Burma

Burmese follow the Theravada form of Buddhism, which is also known as Hinayana Buddhism and the doctrine of the elders or the small vehicle. In Theravada Buddhism, it is up to each individual to seek salvation and achieve nirvana.

In A.D. 1040 king Anawrahta was converted to Theravada Buddhism from southern Burma. Theravada mixed with indigenous beliefs and became dominate and known as Burmese Buddhism (similar to Theravada practiced in Sri Lanka, Laos, Cambodia and Thailand) in northern Burma. Mahayana Buddhism, the other main school of Buddhism, for the most part disappeared. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Hong Sar Channaibanya, a Burmese-born Australian, wrote: “From the age of 13 to 23, for a decade, I lived in Buddhist monastic institutions. I did basic and then higher Buddhist education over this time which gave me a rich knowledge of Burmese culture. The Buddhist community dominates the general population although other faiths also have long histories in Burma. A large majority of people practice Buddhist traditions at home. Respecting adults or parents is a common attitude of each individual. Preserving the principle of Buddhism is also import ant to each individual. Forgiveness is a core concept and perhaps the best quality of Buddhist Burmese. On the other hand ignorance is regarded as a sin. The Buddhist community’s emphasis on forgiveness and caring for each other in the family and community at large dominate Burma’s society. People live in a collective culture at home with parents who hold great power in family. In comparison, individual rights and choice are core cultural elements in a country like Australia. There is an unfamiliar culture of ‘complaint and disagreement’ on issues that impact on both the individual and family’ matters. This is a large cultural shift for people from Burma. [Source: Hong Sar Channaibanya, Canberra, Australia May 2010 /]

See Buddhism, Religions in Asia

Early History of Buddhism in Burma

Buddhism is believed to have been introduced to Burma by missionaries sent by the Indian emperor Ashoka in the third century B.C. Tradition, basing itself upon the Sinhalese chronicle, the Mahavamsa, attributes the origins of Buddhism in Myanmar to the mission of Sona and Uttara who, in the 3rd century B.C., came to Suvannabhumi, usually identified with That on, on the Gulf of Mottama. Some modern scholars dispute this point. But even if tradition is to be ignored, there can be no denying that Buddhism was already flourishing in Myanmar in the 1st century A.D., as attested by the archaeological evidence at Peikthanomyo (Vishnu City), 90 miles southeast of Bagan. Buddhism was also an invigorating influence at Thayekhittaya, near modern Pyaymyo 160 miles south of Bagan, where a developed civilization flourished from the 5th to the 9th century.[Source: baganmyanmar.com ]

As evidenced by artifacts and inscriptions, an array of religions were practiced during the Pyu period such as Hinduism and in particular Vaishnavism, Theravada Buddhism, Mahayanna Buddhism, Tantrayanna Buddhism and a vast range of uncodified animist beliefs and rituals. By the end of this period, the major Animist spirits (Nats) had been subordinated to Theravada Buddhism which become the religion of choice among the lowland rice farmers and Theravda Buddhism has remained the predominant religion in Burma until the present day. =

The Tibeto-Burman-speaking Pyu entered the Irrawaddy valley from present-day Yunnan in the 2nd century B.C., and went on to found city states throughout the Irrawaddy valley. The Pyu were the earliest inhabitants of Burma of whom records are extant. During this period, Burma was part of an overland trade route from China to India. Trade with India brought Buddhism from southern India. By the A.D. 4th century, many in the Irrawaddy valley had converted to Buddhism. The Pyu calendar, based on the Buddhist calendar, later became the Burmese calendar. Latest scholarship, though yet not settled, suggests that the Pyu script, based on the Indian Brahmi script, may have been the source of the Burmese script. [Source: Wikipedia +]

spread of Buddhism out of India

The archaeological finds also indicate a widespread presence of Tantric Buddhism, Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism. Avalokites'vara (Lokanatha) (called Lawkanat in Burmese; Tara, Manusi Buddhas, Vais'ravan.a, and Hayagriva, all prominent in Mahayana Buddhism, were very much part of Pyu (and later the Pagan) iconography scene. Various Hindu Brahman iconography ranging from the Hindu trinity, Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, to Garuda and Lakshmi have been found, especially in Lower Burma. Non-Theravada practices such as ceremonial cattle sacrifice and alcohol consumption were main stays of the Pyu life. Likewise, the greater prominence of nuns and female students than in the later eras may point to pre-Buddhist notions of female autonomy. In melding of their pre-Buddhist practices to Buddhist ones, they placed the remains of their cremated dead in pottery and stone urns and buried them in or near isolated stupas, a practice consistent with early Buddhist practices of interring the remains of holy personages in stupas. +

From the A.D. 4th century onward, the Pyu built many Buddhist stupas and other religious buildings. The styles, ground plans, even the brick size and construction techniques of these buildings point to the Andhra region, particularly Amaravati and Nagarjunakonda in present-day southeastern India. Some evidence of Ceylonese contact is seen by the presence of Anuradhapura style "moonstones" discovered at Beikthano and Halin. By perhaps the 7th century, tall cylindrical stupas such as the Bawbawgyi, Payagyi and Payama had emerged at Sri Ksetra. +

King Anawrahta and Theravada Buddhism

Aruguably King Anawrahta’s greatest and most lasting achievement was was the introduction of Theravada Buddhism to Upper Burma after Pagan's conquest of the Thaton Kingdom in 1057. Supported by royal patronage, the Buddhist school gradually spread to the village level in the next three centuries although Tantric, Mahayana, Brahmanic, and animist practices remained heavily entrenched at all social strata. [Source: Wikipedia]

A war broke out between King Anawrahta of Pagan and the Mon King Manuhar. when King Manuhar refused to hand over sacred Buddhist texts to Pagan. After the war. King Manuhar was captured and was kept under restrictions for a long time in Pagan until his death. He built Manuhar Temple while he was there.

statue of King Anawrahta at the National Museum of Myanmar

According to Paganmyanmar.com: “Anawrahta was a king of strong religious zeal as well as one of great power. His clay votive tablets, made to acquire merit, are found widely in Myanmar from Katha in the north to Twante in the south. These votive tablets usually have, on the obverse, a seated image of the Buddha in the earth-touching attitude, with two lines underneath which express the essence of the Buddhist creed: ‘The Buddha hath the causes told/ Of all things springing from causes; / And also how things cease to be, / 'Tis this the Mighty Monk proclaims.’ On the reverse would be the prayer: ‘Desiring that he may be freed from samscira the Great Prosperous King Aniruddha himself made this image of the Lord.’” [Source: Paganmyanmar.com **]

“The chronicles relate that a monk from Thaton, Shin Arahan, came to Anawrahta in Pagan and preached to him the Law, on which Anawrahta was seized with an ecstasy of faith and said, "Master, we have no other refuge than thee! From this day forth, my master, we dedicate our body and our life to thee! And, master, from thee I take my doctrine!" Shin Arahan further taught Anawrahta that without the Scriptures, the Tipitaka, there could be no study, and that it was only with the Tipitaka that the Religion would last long. Anawrahta, informed that there were thirty sets of the Tipitaka at Thaton, sent an envoy with presents to its king,Manuha, and asked for the Tipitaka. Manuha refused, on which Anawrahta sent a mighty army, conquered Thaton, and brought back the thirty sets of Tipitaka on Manuha's thirty-two white elephants, as well as Manuha and his court and all manners of artisans and craftsmen. **

“The establishment of Theravada Buddhism as the dominant religion of Myanmar did not preclude the existence of other schools and beliefs. Prior to the coming of Buddhism there existed in Myanmar a folk religion which involved the worship of nats or spirits to whom offerings were made. The spirits were not only those of nature, but also of personages who had died a violent or tragic death. At Pagan the cult of the Mahagiri ("Great Mountain") rato-brother and sister who had their abode at Mount Popa, 40 miles to the southeast of Pagan-was particularly strong This folk religion persisted in a symbiotic existence with Theravada Buddhism at Pagan. But that was not all. Mahayana Buddhism, with its pantheon of Bodhisattvas who had postponed their entry into nirvana to help their fellow creatures find salvation, also continued to have a tenuous presence at Pagan, a presence which can be detected in some of the details of the monuments. There was a presence too of Hinduism, which the court drew upon for some of its rituals and ceremonies.” **

Buddhist Beliefs

Myanmar Buddhists emphasize the Three Ratana (the Three Gems). 1) Buddha: the enlighten one; 2) Dhamma: the teachings; 3) Sangha: the follower monks.

Central to the beliefs of Theravada Buddhists is karma, the concept that good begets good and evil begets evils. Another belief is that all living things go through reincarnation. If a person has committed sins he or she will be reincarnated into a lower level being such as an animal or suffer in Hell. On the other hand if he or she has done good deeds, he or she will be elevated to a higher level of existence to the world of devas. The ultimate aim in life according to Buddhist belief is to escape the cycle of rebirth and reach Nirvana. [Source: Myanmar Travel Information **]

Meritorious deeds that will help further a person on the road to achieve include giving donations (especially to monks) and abiding by the Five Precepts of Buddhism and practicing Bavana (meditation).The Five Precepts are exhortation not to kill, steal, lie, drink alcohol or commit adultery. The Five Precepts are codes of conduct for laypeople. There are also Eight. Nine and Ten precepts meant to be practiced by more serious lay devotees. The Jemghas or monks have to abide by the 227 rules of conduct or vinayas. **

Buddhists believe that those who die are reborn in a form that is in keeping with the merit they accumulated while alive. The cycle of death and rebirth is believed to continue as long as ignorance and craving remain. The cycle can be broken only through personal wisdom and the elimination of desire.

Buddhist Customs in Myanmar

release of caged birds

Caged sparrows are sold everywhere. Buddhist believe to let them free to earn merit. At temples, each morning statues of Buddha have their mouths cleaned with a tamarind branch. On Inle Lake people make fabric for monk’s cloaks from lotus flower stems.

On auspicious occasions, offerings are dedicated and given to Lord Buddha and the assemblage of celestials. The offerings usually contains three or five hands of bananas, one coconut and Eugenia sprigs.

In Myanmar no deed is considered more worthy than to build a pagoda. Making a pilgrimage to such shrines is also considered a worthy religious act. On the sides of roads, groups of small girls wait to collect coins from passing cars and minibus to build shrines and temples. Joshua Kurlantzick wrote in the Washington Post “Crumbling pagodas overrun with vines lined the road, their statues worn smooth by years of worshipers touching the faces. As I wove past water buffalo and dilapidated ox carts, children and young adults flagged me down, rattling aging silver bowls for me to stuff with wads of kyat, the Burmese currency, to be used to restore these treasures. [Source: Joshua Kurlantzick, Washington Post , April 23, 2006]

Monks should be greeted with three Southeast Asian bows. When talking to a monk try if you can to have your head lower than his. This can be achieved by bowing slightly or sitting down. If a monk is sitting down you to should also be sitting down. Women should not touch a monk or give objects directly to him (instead place the object on a table or some other surface near the monk). On buses and trains, people customarily give up their seat to monks.

family praying at a temple in Myanmar

Buddhist Temple Customs in Myanmar

People are supposed to take off their shoes and socks before entering a temple and leave umbrellas outside. There are places to leave your footwear. Visitors are also expected to be neatly dressed. Hats should be removed. Short sleeve shirts, short pants, short skirts and pants for women are generally regarded as inappropriate attire but are often grudgingly tolerated from foreigners.

Some cultures require visitors to only take off their shoes when entering a temple but in Myanmar they are required to take off their shoes and socks when entering the temple grounds. Some people wash their feet before entering a temple. In Myanmar you must take off your shoes and socks even if the temple area is 16 square miles in area like at Pagan or 775 foot high like Mandalay Hill. W.E. Garret wrote in National Geographic, "Since thorns will get you if you step off the blazing walks, I found it best to avoid temple visits in the heat of the day.” On how locals viewed the custom, Paul Theroux wrote in the "The Great Railway Bazaar”: “Remove shoes and socks but also spit and toss cheroot ashes on the temple floors.”

Always walk clockwise around Buddhist monuments, thus keeping the religious landmarks to your right (this is more important in Tibet and Himalaya areas than it is in Southeast Asia) Don't walk in front of praying people. Don’t take photos during prayers or meditation sessions. Don’t use a flash. As a rule don’t take photos unless you are sure it is okay. Taking photographs of Buddhist statues or images is considered to be sacrilegious.

Buddha images are sacred objects and one should not pose in front of them or point their feet at them. When sitting down many local people employ the “mermaid pose” to keep both feet pointed towards the rear. Photographing Buddha images is considered disrespectful, but again, is tolerated from foreign tourists.

Praying is done by prostrating oneself or bowing with hands clasped to their foreheads from a standing or seated position in front of an image of Buddha. Prayers are often made after tossing a coin or banknote into an offering box and leaving an offering of flowers or fruits or something else. Many people visit different altars, leaving some burning incense and praying at each one. Other bow at the altar and sprinkle water, a symbol of life. Other still, kowtow before shrines, bend down and stretch three times. In big temples money can be left in a donation boxes near the entrance. If there is no donation box. You can leave the money on the floor.

Paul Theroux wrote in the "The Great Railway Bazaar” that in Burmese temples one should remove shoes and socks but also spit and toss cheroot ashes on the temple floors: “We were standing at the foot of Mandalay Hill, before two towering stone lions and a sign FOOT WEARING IS FORBIDDEN. I took off my shoes—"Stockings too," said the Burman apologetically—and socks, and began climbing the holy stairs. He kicked off his rubber sandals and followed me, muttering, "Omega, Omega." And spitting. "Foot wearing" is forbidden, but bicycles are not—provided they are pushed and not ridden—and neither is spitting. Dodging great gouts of betel juice, I climbed, and soon others joined us.”

Praying at Shwedagon Pagoda

Shwedagon Pagoda

Recalling a visit to Shwedagon Pagoda in the dol days, an elderly writer with the Myanmar Travel Information wrote: “I remember my father was always the first to finish his prayers and we three girls next. My grandmother and mother being more devout took longer. I remember I would squirm and fidget with impatience at their seemingly endless prayers. My father however kept us in check by pointing out the significant features of the graceful and symmetrical bell-shaped golden pagoda and its surroundings. Then all of us. (I think including my father). would sigh in relief as my mother approached the tall vases kept in a row in front of the Buddha images to arrange her flower offerings. [Source: Myanmar Travel Information ~]

“Then came the obligatory circambulation of the pagoda and stops at the various planetary posts of our respective birthdays of the week. We would each say a short prayer and sluice water and cleanse the Buddha image. the image of the planet spirit and the symbolic animal of the day of the week. That would take about another hour and I was always thankful my parents were both Wednesday-born and my sisters being twins. Sunday-born. because it meant two stops less to make. ~

Buddhism and Life in Myanmar

According to Brigette and Robert on Tour, Blog: “Compared to Thailand, Buddhism permeates many more aspects of social life in Myanmar. We constantly see locals praying and meditating in the country’s beautiful and pompous pagodas (temples). There are also over 50,000 monasteries and we encounter monks literally everywhere. We like it; it’s something new for us and it’s interesting to watch them or their interactions with the people. They are treated respectfully and kind by everyone. For instance, when we travel with local buses, we notice that people usually give their seat to a monk if no other place is available. Although the population is so poor, the nation is very giving and generous towards Buddhism (or monks) as their belief promises the re-birth of your soul in a new body. [Source: Brigette and Robert on Tour, Blog ]

Bhamo monastery

“In every city we could see hundreds of monks in the early morning or shortly before sunset marching through the main streets. Every one of them carries a black bowl with both hands. Then, locals start to come out of their houses and they donate either food or money. In theory, monks are allowed 2 meals per day (only in the morning); meals after 12 PM until the next day are actually not allowed and every monk should basically live off alms only. Interestingly, all Myanmar Buddhist men are expected to live in a monastery for at least twice in their lifetime. At first we thought that this might be the reason, why we run into so many monks.

“Well, but some truthful locals taught us better. Unfortunately, you encounter more and more “fake monks”. The reason for it is a simple act of survival. Hunger, poverty and a corrupt military regime are the population’s primary sorrows. Many parents don’t earn the money necessary to feed their children. Hence, families start sending their boys (or girls) in a monastery (or nunnery), hoping the community is “giving” enough so their children will survive. Others choose an undercover life as monks in their adulthood when there is no way out. It’s sad when a peaceful religion, such as Buddhism, is overshadowed by poverty and fake devotees. But somehow we can even understand this development. After all, we see the poor living conditions of the people around us with our own eyes!

Buddhist Saints and Pilgrimage Sites in Myanmar

Describing his encounter with Buddhist saints and shrines on a kayak trip on the Irrawaddy River, Kira Salak wrote in National Geographic, “Docked beside one village, I find a small, lavishly decorated shrine on a wobbly bamboo raft—the first of a handful of such shrines I will see along the river. Inside is a bronze statue of Shin U Pa Gota, the "saint" of all waters. Local villagers have left offerings of flowers, rice cakes, and locks of hair at his altar. According to legend, Shin U Pa Gota grew up a troubled boy until the Buddha visited him and brought him instant enlightenment. From that moment, he spent his time meditating in the Irrawaddy. [Source: Kira Salak, National Geographic, May 2006 /]

“He is the saint of boatmen, of fishermen, of anyone who relies on the river. Bowing before him, I hope he is the saint of kayakers, too. In another day or two, the villagers will set the raft loose so it can continue down the river, bringing blessings to the next village that takes it in. I wonder if the raft will make it all the way to the end of the river. I can hardly imagine that end for myself now, the river opening wide, taking me into limitless blue waves. Past the town of Bhamo, my paddling becomes a pilgrimage, each bend in the river, each rise of a hill prom―ising the sight of a bright white pagoda pointing heavenward. Riverside temples smell of sandalwood incense and jasmine flowers. Bells on pago―da steeples tinkle in the breeze. The river winds past pristine 800-foot (240-meter) high cliffs leading to Shwe Kyundaw—Golden Royal Island—where thousands of stupas rise from a tiny island barely half a mile (0.8 kilometers) long. /\

Taung Kwe Pagoda

“I park my kayak on a sandbar near white steps that rise from the water's edge. Everything is strangely silent. No one is around; to the Burmese people, the Golden Island is an unspeakably holy place on the Irrawaddy, where the Buddha himself is said to have pointed, announcing that an island would arise. And not just any island, but a place where a pagoda would be built along with 7,777 stupas, each to contain a relic from his own body after he died. The Golden Island rose as prophesied, and more than 2,500 years later the promised stupas still stand, crumbling from the heat and dust of eons. /\

“An old man in saffron robes greets me with a smile and a bow. He is the head monk, the Venerable Bhaddanta Thawbita. At 82 years old, he looks as much a relic of the ancient island as its stupas. He has lived on the Golden Island his entire life, beneath its arching bodhi trees and golden pagoda. During World War II, he watched as Japanese soldiers hid among the stupas, prompting Allied Forces to bomb the entire island. Two buildings survived the damage completely unscathed: the main temple and a crypt where four sacred statues—depicting the Buddha's previous incarnations—are kept, each believed to contain his actual blood. /\

“They are considered such holy objects that in 1997 General Khin Nyunt—since ousted from the ruling junta—decided he wanted to move them from the island to a special temple in the capital. Thawbita strongly cautioned him against it. Witnesses later described how at the moment Nyunt reached the river with the statues, the sky grew dark and a violent storm began. Terrified, the chastened general promptly returned them. Busy with visiting locals, Thawbita has his assistant monk, 67-year-old Ashin Kuthala, guide me into the temple. I expect the statues to be stored deep in a vault, far from visitors, but instead they rest on silk sheets inside a gilded cage just a few feet from passersby. I find their close proximity a rare gift. I gaze at the large padlock on the metal door. I ask Kuthala if he ever opens the door to the cage. "Only for VIPs," he says. "For prime ministers, heads of state." "Oh." I study the statues. I press my case. Kuthala takes a moment for consideration—and then goes to get the keys. He asks me to sit on the floor just outside the chamber. Unlocking the door, he goes inside and brings out one of the statues. Holding it, he asks me to pray. He places the statue on top of my head and begins reciting something from scripture. My eyes brim with tears. I'm lost in time.” /\

Elegant Lotus Robe of Myanmar

In Myanmar, where Theravada Buddhism flourishes, yellow robes have been offered to the Lord Buddha in different seasons for many hundreds of years. The robes are known as Waso-thingan, Kahtein-thingan, Matho-thingan, Kyar-thingan and Pantthaku-thingan. The Waso-thingan is the robe offered on the occasion of Wazo, the three-month Lenten period from round about July to October. The Kahtein-thingan is the robe that is offered to the Buddha and his congregation of monks—the Sangha—at the end of Lent. This robe must not be offered to a monk of one's acquaintance or choice but to the Sangha in general. The Matho-thingan—literally meaning “the robe that has not decayed”—is woven on the full moon night of Tazaungmon and which must be completed before the sun rises the next day for offering at sacred Images of the Buddha. Some of the latter robes are woven with yarn from the lotus.[Source: Myanmar Travel Information =]

monks wearing their traditional robes in Myanmar

The very first Pantthagu-thingan was the robe sewn by The Buddha himself with remnants of discarded clothing. This was in adherence to the vow of poverty –– no costly robes, no silks or velvets, just a simple garment patched from torn pieces of cloth — a robe to clothe oneself in decency and modesty. The Buddha laid out the scraps of cloth in the pattern of cultivated fields. each enclosed by low dykes. This pattern is still adhered to in making of robes for the Sangha. =

Some regard the lotus robe as the noblest and most sacred garment because it is meant as an offering to the future Buddha aspiring for Enlightenment or Buddhahood. According to religious texts the tradition of the lotus robe emerged a long time ago. Thar Lay Taung Sayadaw U Tay Zeinda from Inlay district states that the lotus robe does not literally mean the robe which is woven from the lotus thread. When this present world, known as the Badda Kabba (the Badda World) came into existence, five buds appeared on a lotus plant and each contained a complete set of Thingan Pareikaya (prescribed articles for use by Buddhist monks). So it was prophesied that five Buddhas would appear in this world who would show the Path to Liberation. =

Then the age-old Thuddawartha Brahmas brought all the five buds to the place where “Ariyas” holy persons lived and offered the sweet-scented lotus robes to them. As only four robes have been so far offered, there is still one robe outstanding. That was said to be the origin of the lotus robe. There are lotus robes which are woven from strands of yarn obtained from the lotus plant and are offered to the Images of the Buddha and in special cases to eminent monks who have been awarded titles for outstanding religious services. Lotus robes are often decorated with patterns of flowers in gold and silver foil to make it as magnificent as possible for offering to Buddha Images in shrines and pagodas.

Sayadaw Shin Ohn Nyo, one of the four ‘shins’ or venerable clerics in Myanmar literature, composed in his ‘Pyo’—or ode of 60 Ghahtas—that a set of Thingan Pareikaya offered to Prince Sidhattha, the future Buddha, by Yatikaya, Lord of the abode of Brahmas, was the fourth one obtained from the lotus flower that had been in the safekeeping of the ancient Brahmas. In accordance with this legend in which Thudawatha Brahmas offered robes obtained from the primitive lotus to the potential Buddhas, Myanmar Buddhists celebrate a symbolic offering of the lotus robe.

Making a Lotus Robe from Lotus Fibers

Lotus silk thread

Weaving a lotus robe from padonmar kyayoe (lotus stems) and kya-kmyin (lotus fibres) by extracting the yarn from the Padonma lotus stalks demands great creativity, imagination and artistic skill. The place where such wonderful robes are woven is Kyaing Khan village in Inlay district near Inlay Lake. Many varieties of lotus flourish in the Inlay Lake but the yarn for the robe is taken from the the Padonma Kyar (the Red Lotus). As the level of the water surface rises. Padonma lotus plants begin to grow in profusion to supply the necessary thread for this special robe. Kyaing Khan village, located in the south of Inlay district, is the only place where lotus robes are woven. It is not easy to produce lotus thread from which the lotus robe is woven. Lotus stems are plucked in the months of Kason and Nayon (May and June) when lotus plants are abundant in the Lake. [Source: Myanmar Travel Information =]

According to traditional belief in the region, local people believe the lotus has supernatural powers and that the lotus must be in full bloom to produce lotus fibres from its stems. So they conduct a ritual at the lotus pond with offerings of nine dishes of food a week before they cut off the stems. At the time of plucking the stems also, nine dishes of food are offered to the guardian spirit of the house where the lotus robe will be woven. After plucking the lotus stems only the soft stems are taken. =

The next day, they prepare to separate the lotus fibres from the lotus stems. First they rub out the thorns on the stem and cut it into two parts. Then these are marked at 5 or 6 places with a knife at intervals of 9 inches or so after which the cut stems are twisted. They then pull out the fibres with wet hands on a special table about 3 feet long made for the purpose. If the lotus stems are left too long they will decompose and the threads obtained will be of no use. So they pull out these fibres the day after they have cut the stems. These fibres are spun on the small pulley in order to prevent them from getting tangled. Next, they are spun again into the spindle from the pulley. Naturally, the lotus likes water and they hold the fibre from the pulley with wet hands while spinning. After that, handfuls of the fibres are put on different shelves of the same size and spun again on to the large pulley to make them stronger and thicker. =

Lotus silk jacket

These strong and thick fibres are spun again almost continuously into a yarn to produce threads. Then these threads are washed and coated with glue to make them ready for special weaving.These ready-made threads are fixed on the loom both for the warp and woof by twisting them into the spinning rod. Now the weaving of the lotus robe can begin. “In weaving the lotus robe, unlike the ordinary yellow robe, it is necessary to adhere to the Buddha’s teachings and to abide by the five precepts,” said one of the old and skilled woman weavers of the lotus robe. She added. “Even if the weaver is not a virgin, she must be a woman of virtue who keeps the five basic precepts of Buddhism”. The loom is also considered to have supernatural powers so it is surrounded with split bamboo fences of diamond-shaped designs used for royal occasions. Banana and sugar cane plants are tied to the fence at suitable intervals. =

For a perfect robe. the outer robe (Aygathi) must be two and a half yards long and under-wear (Thinbine), six yards long. The weaver must weave ten yards to get a perfect lotus robe. About 220,000 lotus plants are required for one set of robes and it takes 60 weavers 10 days to complete one set. The process from the cutting of the stems to the finished robe takes one month. As the lotus is a hydrophyte, lotus threads are continuously sprayed with water as they are woven and pressed between rollers to yield thicker density. The natural color of the woven robe is ivory-colored, but it is dyed in what is locally called a deep jack-fruit color somewhat like old gold.. Although the length, size and color are the same as the ordinary robe, it is not so heavy but is light, strong and much more beautiful. You can smell the fragrance of lotus from a freshly woven lotus robe. This lotus robe can give coolness in the hot season and warmth in the cold season.

Government Support of Theravada Buddhism in Myanmar

According to the U.S. Department of State: “Although the country has no official state religion, the government continued to show a preference for Theravada Buddhism through official propaganda and state support, including donations to monasteries and pagodas, encouragement of education at Buddhist monastic schools, and support for Buddhist missionary activities. In practice nearly all promotions to senior positions within the military and civil service were reserved for Buddhists. Article 361 of the constitution notes that the government “recognizes the special position of Buddhism as the faith professed by the great majority of the citizens of the Union,” and Article 362 adds that it “also recognizes Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Animism as the religions existing in the Union at the day of the coming into operation of this Constitution.” [Source: U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor International Religious Freedom Report for 2011 ^]

Four-Sided Buddha at Ko Yin Lay Hill in Pano

“The Ministry of Religious Affairs Department for the Perpetuation and Propagation of the Sasana (Buddhist teaching) oversees the government’s relations with Buddhist monks and schools. The government continued to fund two state Sangha universities in Rangoon and Mandalay that trained Buddhist monks under the purview of the SMNC. The state-funded International Theravada Buddhist Missionary University in Rangoon, which opened in 1998, has a stated purpose “to share the country’s knowledge of Buddhism with the people of the world.” ^

“Buddhist doctrine remains part of the state-mandated curriculum in all government-run elementary schools. Students at these schools can opt out of instruction in Buddhism and sometimes do, but all are required to recite a Buddhist prayer daily. Some schools or teachers may allow Muslim students to leave the classroom during this recitation, but there does not appear to be a centrally mandated exemption for non-Buddhist students. ^

State-controlled media frequently depicted government officials and family members paying homage to Buddhist monks; offering donations at pagodas; officiating at ceremonies to open, improve, restore, or maintain pagodas; and organizing ostensibly voluntary “people’s donations” of money, food, and uncompensated labor to build or refurbish Buddhist shrines nationwide. The government published books on Buddhist religious instruction. ^

Buddhism, Myanmar and Aung San Suu Kyi

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “It is impossible to understand Aung San Suu Kyi, or Myanmar, without understanding Buddhism. The country’s liberation hero, Aung San—father of Aung San Suu Kyi—grew up in a devout Buddhist household and attended a monastic school where monks inculcated the Buddhist values of “duty and diligence.” In 1946, not long before his assassination by political rivals in Yangon, Aung San delivered a fiery pro-independence speech on the steps of Shwedagon Pagoda, a 2,500-year-old, gold-leaf-covered temple revered for a reliquary believed to contain strands of the Buddha’s hair. On those same steps, during the bloody crackdown on the pro-democracy movement in 1988, Aung San Suu Kyi was catapulted to the opposition leadership by giving a passionate speech embracing the Buddhist principle of nonviolent protest. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian magazine, September 2012]

“Aung San Suu Kyi has invoked Buddhism repeatedly in her calls for peaceful protest and passive resistance to military rule. When I met Aung San Suu Kyi after her release from house arrest, she spoke at length about the role that Buddhism had played during her confinement. It had given her perspective and patience, she said, an ability to take the long view. This was especially important during the last seven years of her imprisonment, when her principal nemesis was Gen. Than Shwe.

Meditation, Buddhism and Aung San Suu Kyi’s House Arrest

Aung San Suu Kyi

Aung San Suu Kyi is a Theravada Buddhist. She has said that mediation has helped her relax and focus her inner awareness on her political goals. She told Alan Clements, "I think a lot of us within the organization have been given the opportunity to develop spiritual strength because we have been forced to spend long years by ourselves under detention and in prison.”

Joshua Hammer wrote in The New Yorker: “Meditation proved invaluable in dealing with the “intense irritation and impatience” that she felt toward her captors. “I would think, Why can’t we just get on and do what needs to be done, rather than indulge in all this shilly-shallying?” she said. “Because I listened to the radio many hours every day, I knew what was going on in Burma, the economic problems, the poverty . . . and I’d get impatient and say, ‘Why are we wasting our time in this way?’ ” The impatience, she said, “didn’t last, because I had the benefits of meditation. Even when I was very annoyed, I would know that within twenty-four hours this would have subsided.” [Source: Joshua Hammer, The New Yorker, January 24, 2011]

Hammer wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “Aung San Suu Kyi found meditation difficult at first, she acknowledged. It wasn’t until her first period of house arrest, between 1989 and 1995, she said, that “I gained control of my thoughts” and became an avid practitioner. Meditation helped confer the clarity to make key decisions. “It heightens your awareness,” she told me. “If you’re aware of what you are doing, you become aware of the pros and cons of each act. That helps you to control not just what you do, but what you think and what you say.” [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian magazine, September 2012 ]

“As she evolves from prisoner of conscience into legislator, Buddhist beliefs and practices continue to sustain her. “If you see her diet, you realize that she takes very good care of herself, but in fact it is her mind that keeps her healthy,” I’m told by Tin Myo Win, Aung San Suu Kyi’s personal physician. Indeed, a growing number of neuroscientists believe that regular meditation actually changes the way the brain is wired—shifting brain activity from the stress-prone right frontal cortex to the calmer left frontal cortex. “Only meditation can help her withstand all this physical and mental pressure,” says Tin Myo Win. It is impossible to understand Aung San Suu Kyi, or Myanmar, without understanding Buddhism. Yet this underlying story has often been eclipsed as the world has focused instead on military brutality, economic sanctions and, in recent months, a raft of political reforms transforming the country.

Myanmar’s Generals and Buddhism

monks protesting in Myanmar

Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “Myanmar’s generals, facing a democratic revolt, attempted to establish legitimacy by embracing Buddhism. Junta members gave lavishly to monks, funded monasteries and spent tens of millions of dollars restoring some of Myanmar’s Buddhist temples. In 1999, the generals regilded the spire of Shwedagon with 53 tons of gold and 4,341 diamonds. An earthquake shook Yangon during the reconstruction, which senior monks interpreted as a sign of divine displeasure with the regime. [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian magazine, September 2012]

“The military lost all credibility during the Saffron Revolution in 2007, when troops shot dead protesting monks, defrocked and imprisoned others, and shut down dozens of monasteries. Monks appeared on the streets with begging bowls turned upside down—a symbol that they would refuse alms from soldiers. This seldom-invoked punishment was tantamount to excommunication.

Thein Sein, Myanmar’s new reformist president, has tried to repair the relationship. One of his first conciliatory acts was to reopen monasteries shut down by the junta. Among nearly 1,000 political prisoners he freed in January and February 2012, many were jailed monks who had participated in the Saffron Revolution. Senior monks say, however, that the damage will take decades to undo. “Daw [an honorific similar to ‘Madam’] Suu is released, which is good, and the government is clean, but still relations are not good,” I was told by Su Rya, the 37-year-old abbot of the Kyeemyindine monastery in Yangon, which played a leading role in the 2007 protests. “Even five years later, we still remember what happened,” he said.

Buddha Replica Relic Is Stolen in Myanmar

In August 2005, the Chicago Tribune reported: “A replica of Buddha's tooth, a holy relic of the Buddhist religion, has been stolen from a temple in a northern suburb of Yangon. The glass casing at the Swedaw Myat — "Tooth Relic" — Pagoda in which the tooth replica had been enshrined was discovered broken Sunday, and the tooth, along with several precious gems, were missing, said an official at the Religious Affairs Ministry. [Source: Chicago Tribune, August 19, 2005]

The replica relic had been kept on a bejeweled pedestal with a jewel-encrusted holder inside the glass case. Soldiers have sealed the pagoda premises, and pilgrims have not been not allowed to visit while the theft is being investigated. There are acknowledged to be only two genuine Buddha's teeth in existence, one in China and the other in Sri Lanka. Buddhists believe the teeth, reportedly found after Buddha was cremated 2,400 years ago, bring peace and good fortune. Beijing lent its genuine tooth to Myanmar for display in 1994 and again from December 1996 to March 1997. When China lent the real tooth, two ivory replicas were carved to be displayed with it, and after the real one was returned to China, one replica was kept at Swedaw Myat and the other in Myanmar's second city of Mandalay.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, caged bird, Buddhist Channel

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, The Irrawaddy, Myanmar Travel Information Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, burmalibrary.org, burmanet.org, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2019