The Buddha on emptiness

EVAṂ ME SUTTAṂ; This is how I heard it

by Patrick Kearney

The Buddha on emptiness

Introduction

In this class we will examine the Buddha’s teaching on emptiness (suññatā).1

Our central text is Mahāsuññatā Sutta (Greater Discourse on Emptiness) (M122), but if we are to gain a full understanding of the Buddha’s approach to emptiness we need to read this text in the context of other texts, in particular its companion sutra, Cūḷasuññatā Sutta (Shorter Discourse on Emptiness) (M121).

One difficulty in grasping the Buddha’s teaching on emptiness is our tendency to project into the early texts the later Mahāyāna understanding of this concept. All subsequent traditions of Buddhism are based on the Nikāyas.

Later Buddhists would reach into the early teachings and extract particular teachings, which perhaps in their early form were mentioned only occasionally, expand them, and turn them into key concepts.

The evolution of the early teaching of dhammakāya into the Mahāyāna concept of dharmakāya as the third “body of Buddha” is one example of this practice. Similarly, the idea of emptiness (śūnyatā) became a shibboleth for the Mahāyāna.

Emptiness was a key concept in the new prajñāpāramitā literature, composed from about 100 B.C. to 500 A.D. The most influential teacher of emptiness was the Indian philosopher Nāgārjuna (probably 2nd century A.D.), whose Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (Root Verses on the Middle) developed a way of understanding emptiness that became foundational to all Mahāyāna streams of Buddhism.2

Most explanations of emptiness written in English are based, either explicitly or implicitly, on Nāgārjuna’s reading of śūnyatā. But here we want to avoid subsequent interpretations and return to the mūla, the foundation, of the Buddha’s teaching on emptiness, as found in Mahāsuññatā Sutta and Cūḷasuññatā Sutta in particular.

===Mahāsuññatā Sutta - the setting===

Our sutra begins with Ānanda and a group of bhikkhus who are busy making robes, and perhaps enjoying themselves in the process.

The Buddha approaches and explains the dangers inherent in company and society.

For the Buddha, noise, company and busyness get in the way of practice, and he wants to make sure that the bhikkhus remember why they ordained in the first place. He says:

A bhikkhu does not shine by delighting in company ... by delighting in society ...

Indeed, Ānanda, it is not possible that a bhikkhu who delights in company ... who delights in society ... will ever obtain at will, without trouble or difficulty, the bliss of renunciation (nekkhammasukha), the bliss of seclusion (paviveka-sukha), the bliss of peace (upasama-sukha), the bliss of awakening (sambodha-sukha).

But it can be expected that when a bhikkhu lives alone, withdrawn from society, he will obtain at will, without trouble or difficulty, the bliss of renunciation, the bliss of seclusion, the bliss of peace, the bliss of awakening. Indeed, Ānanda, it is not possible that a bhikkhu who delights in company ... who delights in 1

Patrick Kearney

society ... will ever enter upon and abide in either the deliverance of mind that is temporary and delectable (sāmāyika kanta cetovimutti) or in that which is perpetual and unshakeable (asāmāyika akuppa cetovimutti).

But it can be expected that when a bhikkhu lives alone, withdrawn from society, he will enter upon and abide in either the deliverance of mind that is temporary and delectable or in the deliverance of mind that is perpetual and unshakeable.

Bhikkhu Bodhi comments that the “deliverance of mind that is temporary and delectable” refers to the jhānas, the meditative “absorptions,” while the “deliverance of mind that is perpetual and unshakeable” refers to the paths (magga) and fruits (phala), which are the stages of awakening.3

The distinction here is between practice and awakening.

Practice is something that we do, and it is therefore necessarily temporary, for as soon as we choose not to do it, it ceases. Awakening is something that is happening to us. We awaken to the way things are, to reality itself.

Both are “deliverances” or “liberations” (vimutti), but they differ in that they represent liberation from different things.

Jhāna is a liberation, in that it liberates us from the hindrances (nīvaraṇa), the disturbances that arise in meditation and obstruct our ease and concentration.

Awakening (sambodha) is a liberation, in that it liberates us, to at least some degree, from the “defilements” (kilesa) of attraction (lobha), aversion (dosa) and delusion (moha), the fundamental disturbances of the heart.

Abiding in emptiness

Here, the Buddha is concerned with the barriers to practice that leads to awakening, and clearly he thinks that getting involved in society is such a barrier. I do not see even a single kind of form, Ānanda, from the change and alteration of which there would not arise sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief and despair in one who is passionate for it and delights in it.

Do not “delight” in company - or in anything for that matter, because “delight is the mūla of suffering,” as the Buddha explained in Mūlapariyāya Sutta. Here, delight and suffering are linked to impermanence.

Whatever we delight in and cling to changes, and so we are perpetually frustrated in our search for satisfaction. We cling to something that we hope will stick around long enough to satisfy us, but there is no such thing.

However, Ānanda, there is this abiding discovered by the Tathāgata: to enter and abide in emptiness internally by giving no attention to all signs (sabbanimittānaṃ amanasikārā).

If, while the Tathāgata is abiding in this way, he is visited by bhikkhus or bhikhunīs, by men or women lay-followers, by kings or kings’ ministers, by other sectarians or their students, then with a mind leaning to seclusion (viveka), tending and inclining to seclusion, withdrawn, delighting in renunciation, and altogether done away with things that are the basis for taints (āsava), he invariably talks to them in a way concerned with dismissing them.

The way out of this situation is the practice of entering into and abiding in emptiness. Emptiness is the abode of a “great person” (mahāpurisa), as the Buddha confirms to Ānanda in the opening of Cūḷasuññatā Sutta, where Ānanda asks him, “I heard and learned this from the Blessed One’s own lips: ‘Now, Ānanda, I often abide in emptiness (suññatā-vihāra).’

Did I hear that correctly, bhante, did I learn that correctly, attend to that correctly, remember that correctly?” It is this question, and Buddha’s affirmative answer, that provides the context for Cūḷasuññatā Sutta.

What characterises this abiding? “Giving no attention to all signs,” according to our text. “Attention” (manasikāra) is essentially focus, the movement of mind that targets one aspect of a sense field and chooses to attend to that, rather than something else.

From this arise the more developed movements of mind we call vāyāma (“energy” or “effort”), samādhi (“concentration”) and sati (“mindfulness,” “bare attention” or “presence”).

These are the three meditation factors of the noble eightfold path.

“Sign” is a translation of nimitta, which Bhikkhu Thanissaro translates as “theme.” Nimitta has a variety of meanings depending on context, but for our purposes we can focus on two uses: as “mental reflex, image,” and as “outward appearance, mark, characteristic, attribute.”

4 In both cases, nimitta indicates something added to experience, and so not the directness itself, the “just thisness” (tathatā) of experience.

In pure samatha (serenity) practice where the meditator cultivates jhāna, “absorption” into a single aspect of experience, the nimitta is the mental image that arises as concentration deepens and which provides a meditation object sufficiently stable and fixed to serve as a basis for attention.

The direct experience of body and mind is too unstable to serve this function; something artificial, mind-made, must be projected onto the transient nature of experience in order to serve as the basis for serenity absorption.

In contrast, vipassanā (insight) meditation uses the transient mind-body process itself as meditation object.

Normally we do not see this transience, and the unsatisfactory and not-self nature that follows from this, because we habitually project the nimittas of permanence, satisfaction and self onto experience.

We have been analysing these projections in terms of conceivings (maññanā) and proliferation (papañca).

“Non-attention to signs” has two aspects. At the mundane (lokiya) level it refers to the insight practice of learning to see experience as impermanent (anicca), unsatisfactory (dukkha) and notself (anattā), rather than projecting the signs of permanence (nicca), satisfactoriness (sukha) and self (atta) onto experience.

In other words, non-attention to signs deconstructs the conceivings (maññanā) and proliferation (papañca) that create our sense of a self-within-her-world, as we have been looking at in Mūlapariyāya and Madhupiṇḍika Suttas.

At the supramundane (lokuttara) level, non-attention to signs indicates the absence of any signs or themes whatever, including the signs of impermanence, unsatisfactoriness and not-self.

In brief, the immature or mundane aspect of non-attention to signs entails not attending to the signs of permanence, etc., and instead attending to the signs of impermanence, etc.; and the mature or supramundane aspect of nonattention to signs entails not attending even to the signs of impermanence, etc.

In this aspect, there is just the pure presence of what is really here. Or, as the commentary to Majjhima Nikāya puts it, attention to the “signless element,” which is nibbāna.5

Notice how after introducing the abiding in emptiness, the Buddha applies it to the situation which inspired his teaching.

If we cultivate this abiding, then we can deal with the world as it comes knocking - “bhikkhus or bhikhunīs, men or women lay-followers, kings or kings’ ministers, other sectarians or their students” - without being distracted from our practice, or from the experience of nibbāna itself.

And notice how this abiding in emptiness is “discovered by the Tathāgata.”

The Buddha is claiming this as a specifically Buddhist practice, ranking it in importance with the four truths.

Entering into emptiness

If there are no “signs,” then what is there? In Cūḷasuññatā Sutta we find an answer to this question.

Here, the Buddha is living at Sāvatthi in the Eastern Park, in the Palace of Migāra’s Mother.

Ānanda asks about the Buddha’s “abiding in emptiness,” and he explains: Ānanda, just as this Palace of Migāra’s Mother is empty (suñña) of elephants, cattle, horses,

and mares, empty of gold and silver, empty of the assembly of men and women, and there is present only this non-emptiness (a-suññata), the singleness dependent on the sangha of bhikkhus (bhikkhu-saṃghaṃ paṭicca ekattaṃ);

so too, a bhikkhu - not attending to the perception of village (a-manasikaritvā gāma-saññaṃ), not attending to the perception of people

- attends to the singleness dependent on the perception of forest (arañña-saññaṃ paṭicca manasikaroti ekattaṃ).

His mind enters into that perception of forest and acquires confidence (pasīdati), steadiness (santiṭṭhati), and resolution (vimuccati).

He understands (pajānāti) thus: “Whatever disturbances there might be dependent on the perception of village are not here; whatever disturbances there might be dependent on the perception of people are not here. There is only this amount of disturbance, the singleness dependent on the perception of forest.”

He understands: “This field of perception is empty (suñña) of the perception of village; this field of perception is empty of the perception of people. There is only this non-emptiness (asuññata), the singleness dependent on the perception of forest.”

In this way he regards (samanupassati) it as empty of what is not there, but as to what remains he understands what is there in this way: “This is” (idam atthīti).

This, Ānanda, is his genuine, undistorted, pure entry into emptiness (yathābhuccā avipallatthā parisuddhā suññatāvakkan ti bhavati).6

Then follows progressively more refined perceptions: the singleness dependent on the perception of earth, on the perception of the base of infinite space, on the perception of the base of infinite consciousness, on the perception of the base of nothingness, on the perception of the base of neither-perception-nor-non-perception, and the singleness dependent on the perception of the signless concentration of mind.

The signless concentration of mind seems to correspond to the state of “giving no attention to all signs” spoken of in Mahāsuññatā Sutta.

We have here a series of progressively more refined states of concentration, something quite commonly found in the sutras.

The “singleness dependent on the perception of earth” is a summary of the four rūpa jhānas (material absorptions), here using earth kasiṇa as meditation object.

Then follows the four arūpa jhānas (immaterial absorptions), and finally the “signless concentration.”

The previous attainments normally refer to serenity practice (although they can also be interpreted as insight practices); the final one to insight practice.

But in all cases the structure is the same. In this “field of perception” something is absent.

It begins as the practitioner simply noticing that the distractions of everyday life are absent when he retires to a quiet place to meditate.

Emptiness, in other words, is absence. Something is “empty” when it is not here, not in our field of experience.

The flip side of emptiness is presence. If something is absent, then what is present? Just “this.” Emptiness

In Saṃyutta Nikāya, Ānanda asks the Buddha why people use the expression “The world is empty.” He replies:

“It is because it is empty of self and of what belongs to self that it is said, ‘The world is empty.’

And what is empty of self and of what belongs to self? The eye, Ānanda, is empty of self and of what belongs to self.

Forms are empty of self and of what belongs to self. Eye-consciousness is empty of self and of what belongs to self. Eye-contact is empty of self and of what belongs to self. ...

Whatever feeling arises with mind-contact as condition - that too is empty of self and of what belongs to self.”7 (S IV.54) (And so on through the other senses.)

“Emptiness” refers to absence, and specifically the absence of “self and what belongs to self.”

Emptiness refers to a quality or mode of experience.

Remember that the Buddha is concerned with the nature of experience from the perspective of the experiencing subject.

I always experience myself as some-one in the midst of some situation.

This entails a sense of possession: this is my body; this is my mind; these are my concerns; this is my happiness or sorrow; these are my friends; this is my world.

“Self” does not refer just to the entity enclosed within this skin; self refers to the entire experienced world, when that world is experienced from the perspective of someone real who is here in the midst of all this, which is also real.

The Buddha is saying that this sense of a self-within-her-world is not real. It’s a projection, something we are working on right now through, for example, conceiving (maññanā) and 4

proliferation (papañca). It’s actually not here. It’s absent. It’s “empty.” But how do we recognise this?

The practice of emptiness is described in a number of suttas in this way:

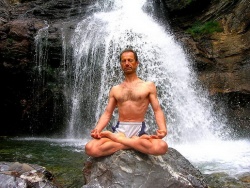

“Here a bhikkhu, gone to the forest or to the root of a tree or to an empty hut, reflects (paṭisañcikkhati) thus: “This is empty of self or of what belongs to self.”

This practice is called “the deliverance of mind through emptiness” (suññatā ceto-vimutti).8 How can we practise this liberation?

How do we discover not-self (anattā) in our vipassanā practice?

By acknowledging, becoming consciously aware of, our failure to discover self. When we contemplate not-self we are not contemplating some special, esoteric aspect of the mind-body process.

Not-self can be seen in any aspect of experience, because self is not a thing, an entity, a specific experience, but a relationship to any experience: “This is mine; I am this;

This is my-self.” Not-self is not a specific experience, but a relationship to any experience: “This is not mine; I am not this; This is not my-self.” Further, self is a relationship to what is not clearly seen; to our dreams, taken as real. Not-self is a relationship to what is clearly seen; to dharmas.

Not-self is what is really happening, what has always been really happening, and contemplating not-self is seeing and tracking what is real.

As we contemplate not-self we are training ourselves to step back from our entanglement in our dreams, to disengage from them, reminding ourselves: “This is not me, and it doesn’t belong to me, and so I don’t have to get caught up in it.”

In this contemplation we are training ourselves to become aware of absence, what is not here, and the space that absence provides.

And we can see how, in Cūḷasuññatā Sutta, the practitioner trains herself to recognise absence, from the gross (“I feel agitated, but the disturbances of normal life are absent”) to the subtle (“I feel that ‘I am,’ but there’s nothing here that I am”).

This is not based on some esoteric philosophy. It’s just that the forest is empty, in the most mundane sense - no people around. We become attuned to absence, so that eventually we will recognise the emptiness, the absence, of self.

And self is always characterised by stories projected on to the purity of experience, stories which involve “me” and the world that define “me.”

Thanissaro gives this example: Say for instance, that you're meditating, and a feeling of anger toward your mother appears.

Immediately, the mind's reaction is to identify the anger as “my” anger, or to say that “I'm” angry.

It then elaborates on the feeling, either working it into the story of your relationship to your mother, or to your general views about when and where anger toward one's mother can be justified. The problem with all this, from the Buddha's perspective, is that these stories and views entail a lot of suffering.

The more you get involved in them, the more you get distracted from seeing the actual cause of the suffering: the labels of “I” and “mine” that set the whole process in motion.

As a result, you can't find the way to unravel that cause and bring the suffering to an end.9

Presence

The other side of absence is presence. If self and what belongs to self is absent, then what is really here?

He understands: “This field of perception is empty (suñña) of the perception of village; this field of perception is empty of the perception of people. There is only this non-emptiness (asuññatā), the singleness dependent on the perception of forest.”

In this way he regards it as empty of what is not there, but as to what remains he understands what is there in this way: “This is” (idam atthīti). This, Ānanda, is his genuine, undistorted, pure entry into emptiness.

The other side of emptiness is tathatā, “suchness,” or “just-this-ness.” When we clear the fog of our projections, step back from our entanglement, drop our identification with our dreams, then experience clarifies. We begin to see clearly. It is just what it is, with nothing added, nothing 5

projected. Awakening entails intimacy. When we drop our projections we become intimate with experience, and within this intimacy liberation takes place. The expression of this “entry into emptiness” is radically simple, matching the radical simplicity of the experience: “This is!” What more can be said?

Plenty, of course, although most of the Buddha’s teaching focuses on the nature of delusion and the practice of deconstructing delusion, rather than attempts to describe the goal of the practice.

We have commented on the inadequacy of language before, and the Buddha is very sensitive to that inadequacy. Nibbāna, the goal of the path, pushes the limits of language. The Buddha is trying to describe freedom to people who are not free.

This means he must fail, since we literally do not know what he is talking about. So the best he can hope for is mystery, but mystery that has us pointing in the right direction - the path.

The danger he faces is that we will grab hold of any concept he gives us and use it to project the existence of some kind of self or the annihilation of some kind of self; in other words, we will cling to and identify with whatever concept he gives us.

So he tries to give us as little as possible to hold on to, as well as pointing out the dangers inherent in holding.

So it’s not that nibbāna represents some mysterious ontological realm which language does not reach; it’s just that any attempt to express anything we have not experienced is bound to fail, and the Buddha is taking due notice of that

When there is no construction of a self and her world, and so a complete release from the pain that constructing a self brings (which is nibbāna), then we can conceptualise this situation from the outside in various ways - the absence of attraction, aversion and delusion;

the absence of projections; the absence of signs; and so on. “Nibbāna is empty of ...”

Maybe we can conceptualise so freely because no concept precisely or exclusively fits.

It just depends on the perspective of the person hearing the concepts:

“It’s not this aspect of dukkha with which you are familiar.”

But all these concepts indicate strategies to attain nibbāna: reduce attraction, aversion and delusion; reduce projections; reduce making signs.

They indicate practices. Nibbāna includes practice, because nibbāna must be lived - practised.

So what is most important in the language we use to describe the goal is that it provides a guide for practice to attain that goal; that it points the person towards nibbāna.

Aññaphala samādhi

Intimacy as practice can be expressed as aññaphala samādhi, “result of knowledge” concentration (A IV.430), or ānantarika “immediacy” (Sn 226). It refers to the consciousness of the awakened one that is such that devas and brahmās cannot find its support.

10 Bhikkhus, when the gods with Indra, with Brahmā and with Pajāpati seek a bhikkhu who is thus liberated in mind, they do not find anything of which they could say:

“This is the support (nissita) of the tathāgata’s consciousness.” Why? A tathāgata, I declare, is untraceable (ananuvejja) here and now (diṭṭheva).”

Alagaddūpama Sutta (M22) This mysterious samādhi is referred to in other texts. For example, in Aṅguttara Nikāya we read this description of the meditating awakened one.

He meditates without dependence on earth so neva paṭhaviṃ nissāya jhāyati, ... without dependence on water ... fire ... air ... without dependence on whatever is seen, heard, sensed, known, attained, sought after, traversed by the mind. He does not meditate on any of that, yet he does meditate.

(A V.324-5)

To meditate “without dependence” on anything, with no “support” is to practice without the mind being fixed on anything - in particular.

Again, this indicates a “signless” concentration (animitta jhāna) resulting in a signless liberation (animitta vimutti).

The verb translated here as “meditates” is jhāyati, from which we get the noun jhāna, “absorption.”

Jhāna normally understood is characterised by the arising and maintaining of a nimitta (“sign”), which must be 6

fixed so that the meditator can keep his mind upon it and become absorbed in it.

The sign defines, and so limits, the jhāna - as earth kasiṇa jhāna (jhāna using earth as object), etc., or as first jhāna, second jhāna, and so on. But here is a jhāna characterised by the absence of a sign, and so the absence of fixity. It is “signless,” an expression of intimacy, of emptiness. Similarly, in Dhammapada we read:

<poem>

For those who do not accumulate

Who fully understand nutriment

Their range is the deliverance

Of emptiness (suññatā) and signlessness (animitta).

Like birds in space

Their track is difficult to trace. (Dhp.92)

“For those who do not accumulate.” “Accumulation” suggests grasping, holding onto some-thing and becoming some-one as a result; relating to experience in terms of “I” and “mine.”

“Who fully understand nutriment.” “Nutriment” again suggests clinging, upādāna, the “fuel” that “feeds” a fire.

Understanding nutriment, how we fuel and feed our heavy sense of ourselves entangled in our world, allows us to disentangle, to deconstruct ourselves.

“Their range is the deliverance/Of emptiness and signlessness.”

One who is liberated from the burden of constructing themselves, who is liberated from the fixity of identity, is free to roam, to move anywhere. “Like birds in space/Their track is difficult to trace.”

Impossible, in fact. Trying to pin down, to define, an awakened one is like following the track of a bird through space. There is nothing left behind to hang on to; only the intimacy of this moment of flight.

Anidassana viññāṇa

At the end of Kevaḍḍha Sutta (D11) we find a mysterious verse that expresses the nature of the consciousness of the awakened one, anidassana viññāṇa (non-indicative consciousness). Consciousness that is non-indicative (viññāṇaṃ anidassanaṃ) Limitless, luminous all around, Here water and earth

Fire and air find no foundation (na gādhati).

Here long and short

Subtle and gross, pleasant and painful,

Here name-&-form

Are destroyed without remainder (asesaṃ uparujjhati).

With the cessation of consciousness (viññāṇassa nirodhena) All this is destroyed.

This verse is an answer to a monk’s question, “Where do the four elements cease without remainder?”

The four elements are those of earth, air, fire and water, which together make up the (experienced) material universe.

The question is about the end of the world, an ontological question based on a third person perspective - the world out there, and its fate.

The Buddha refuses to answer and instead reframes it into a phenomenological question, based on a first person perspective.

Where does our experience of the world end? Our sense of my-self-within-a-world? Where do the four elements find “no foundation?”

The elements - and everything else - find no foundation, no ground or basis, in a particular form of consciousness, one in which “name-&- form” (nāma-rūpa) are entirely destroyed.

Name (nāma) is characterised by intentionality. Our states of mind - beliefs, desires, intentions, perceptions and so on - are all about something in the world; they are directed at objects and situations. If we believe, we believe something; if we desire, we desire something; and so on.

In terms of meditation practice, intentionality reminds us that knowing always has an object: when there is knowing, there is always some thing which is known, the reference or object of knowing.

Knowing is always knowing-of.

So nāma is the process of the mind reaching out to sense data and 7

organising it into a self-within-a-world. Form (rūpa) is what is shaped, the “of” found in “knowing-of.”

Name-&-form arise and cease along with and dependent upon consciousness (viññāṇa).

Consciousness in its most elemental sense is the presence of the phenomenon, the presence of what is present.

In general terms we can say that our experienced world is divided into a duality of the process of knowing and that which is known.

For example, if I stub my toe I “know,” or am conscious of, the sensation of pain. The knowing of the pain is consciousness; the pain itself is the object of consciousness. Speaking more precisely, I experience an undiluted consciousness in the very first moment when my toe impacts upon a hard object.

For a single moment there is an elemental knowing; then suddenly I know a situation already interpreted: pain, anger directed at the object that I struck, irritation at myself for being so careless, and so on.

There is a shift from the simplicity of pure awareness to a complex situation where I already live in an organised and coherent - although painful - world in which “I” have stubbed “my toe” on “that” - which should not have been there!

This complex world has been organised and interpreted by name-&-form; its presence is consciousness; its presence to me is consciousness together with name-&-form.

The relationship between consciousness and name-&-form is one of interdependence or mutuality.

Where there is something known, there is the knowing of it; when there is a knowing of something, there is something known.

One way of expressing this is to say that consciousness needs a foundation, somewhere to ground.

It needs to be “established” somewhere, on something. Only then can consciousness be discerned, for the foundation of consciousness provides the “of” when we say consciousness is a knowing-of. Only in relationship to this “of,” the foundation of consciousness, can consciousness itself, the knowing itself, be discerned.

This foundation, the “of” of knowing-of, is name-&-form. In brief, name-&-form together with consciousness constitutes this entire meaningful world, along with the person who experiences it, now.

The arising of name-&-form together with consciousness constitutes the arising of this entire meaningful world along with the person who experiences it; and the cessation of name-&-form together with consciousness constitutes the cessation of this entire meaningful world along with the person who experiences it.

When “name-&-form are destroyed without remainder,” what is left?

Consciousness, but not consciousness in the normal sense - consciousness that is established on something, indicating something, and so defined and limited by that something.

What remains is non-indicative consciousness (anidassana viññāṇa).

The meaning of anidassana is clarified in Kakacūpama Sutta (M21), where the Buddha asks:

“Suppose a man came with crimson, turmeric, indigo, or carmine and said: ‘I shall draw pictures and make pictures appear in space (ākāsa).’

What do you think, bhikkhus? Could that man draw pictures and make pictures appear in space?”

“No, bhante. Why? Because space is formless arūpī and non-indicative anidassana ...”

We cannot paint on sky because sky has no form, no ground on which paint can rest; and it does not manifest as anything or indicate anything.

Like the track of a bird, there is nothing there to point to.

Non-indicative consciousness refers to a consciousness that is not stuck anywhere, that is not defined by any thing. It is untraceable and is not dependent on anything.

It may be found in a samādhi that does not construct anything out of experience, but simply registers what is happening without either clinging or rejection - “This is!” Pure presence, with nothing added. If we are looking for an object for this consciousness, we could say that its object is nibbāna itself.

This is the consciousness of the entry into emptiness, the abiding in emptiness. 8

The way to emptiness

Which brings us back to Mahāsuññatā Sutta. How does one cultivate this abiding? What is the path that leads to it? The Buddha explains:

Therefore, Ānanda, if a bhikkhu should wish: “May I enter upon and abide in emptiness internally,” he should steady his mind internally, quiet it, bring it to singleness, and concentrate it.

And how does he steady his mind internally, quiet it, bring it to singleness, and concentrate it? ...

Then follows instructions on the four jhānas, the standard formulas for the cultivation of concentration.

But then we have a shift, when the Buddha starts to speak of the barriers to concentration.

Again, we might see here a reference to the situation that inspired this teaching. Caught up in involvement with the world, we may have difficulty cultivating the necessary concentration.

Then he gives attention to emptiness internally ... externally ... internally and externally.

While he is giving attention to emptiness internally and externally, his mind does not enter into emptiness internally and externally or acquire confidence, steadiness, and decision. When that is so, he understands thus:

“While I am giving attention to emptiness internally and externally, my mind does not enter into emptiness internally and externally or acquire confidence, steadiness, and decision.” In this way he has clear understanding (sampajañña) of that. ...

Then that bhikkhu should steady his mind internally, quiet it, bring it to singleness, and concentrate it on that same sign of concentration as before. Then he gives attention to emptiness internally ... externally ... internally and externally.

While he is giving attention to emptiness internally and externally, his mind enters into emptiness internally and externally and acquires confidence, steadiness, and decision. When that is so, he understands thus:

“While I am giving attention to emptiness internally and externally, my mind enters into emptiness internally and externally and acquires confidence, steadiness, and decision.” In this way he has clear understanding (sampajañña) of that.

The reference to “giving attention to emptiness internally and externally” refers to seeing emptiness in both our own subjective processes and in the objective world within which we live.

It implies an increasingly “objective” relationship to events, seeing and responding to them in the same way regardless of whether they occur in ourselves or in others.

The sense of ownership we have over events fades; our emotional investment in the way we feel we should be, and others should be, and this experience should be.

Instead, we encounter a developing intimacy with how things really are, and a greater freedom of response to situations. But the practice may not work, for any number of reasons. So the meditator persists, working on his obstacles, and eventually succeeds. In both cases, “he has clear understanding (sampajañña) of that.”

Sampajañña has been translated as “clear comprehension” (Nyanaponika Thera) and “full awareness” (Bhikkhu Bodhi).

I translate it as “clear understanding,” to include the significance of the root ñā, “to know,” that it is based on. “Sampajañña” is normally found in the compound “satisampajañña,” “mindfulness-&-clear-understanding.” The two mental factors are intimately connected, such that if one is present both are present.

Which one is mentioned depends on context - which aspect of mindfulness practice is being emphasised. Mindfulness is presence. It provides the space within which we practice clear understanding.

Clear understanding is the knowledge (ñāṇa) or wisdom (paññā) that arises based on mindfulness.

Clear understanding is the intelligence that accompanies presence. Or, we could say that satisampajañña refers to intelligent presence.

Clear understanding acts as a perspective that allows a kind of meta-awareness, an awareness of awareness that enables the practitioner to monitor her state of concentration and liberation, and therefore to monitor her progress or lack of progress.

We spoke earlier of how an awareness of emptiness entails an awareness of absence, of what is not present as well as what is present.

This implies a wider mindfulness, or meta-mindfulness, that requires an intelligence within presence rather than just mechanically “noting” a meditation object. Much of the rest of Mahāsuññatā Sutta focuses on the functioning of this intelligence.

===[[Full awakening]===]

Mahāsuññatā Sutta describes the full awakening of the practitioner in this way: Ānanda, there are these five clung-to aggregates, in regard to which a bhikkhu should abide contemplating arising and cessation in this way:

“Such is form, such its arising, such its disappearance; such is feeling, such its arising, such its disappearance; such is perception, such its arising, such its disappearance; such are formations, such their arising, such their disappearance; such is consciousness, such its arising, such its disappearance.

When he abides contemplating the arising and cessation in these five clung-to aggregates the conceit “I am” based on these five clung-to aggregates is abandoned in him.

When that is so, that bhikkhu understands: “The conceit ‘I am’ based on these five clung-to aggregates is abandoned in me.” In that way he has full awareness of that.

This describes the practice of satipaṭṭhāna, the domains of mindfulness.

The practitioner cultivates the perception of impermanence (anicca-saññā) by tracking the changes within experience.

Nothing stands still. Nothing stays the same. We begin by seeing that the things we are mindful of are changing; then we begin to realise change itself.

Our seeing the things that change moves from foreground to background, and our seeing the fact of change itself moves from background to foreground.

We are no longer contemplating “this,” which arises and ceases, but arising and ceasing itself, instantiated in and as “this.”

From contemplating something and noticing that it arises and ceases, we contemplate arising and ceasing itself, noticing that this universal process - which is both internal/subjective and external/objective - manifests in and as this particular something.

From the perception of impermanence (anicca-saññā) comes the perception of suffering and notself.

Seeing the transient nature of experience we realise that nothing can be relied upon, and attain the perception of suffering within impermanence (anicce dukkha-saññā).

Seeing the transient, uncontrollable and painful nature of experience we realise we cannot claim any experience as “me” or as belonging to “me,” and attain the perception of not-self within suffering (dukkhe anatta-saññā).

At last we abandon our sense of identification and ownership regarding experience, and along with it the conceit “I am.”

This is full liberation.

Perceiving impermanence allows us to deconstruct the conceivings, proliferation and projections through which we add to the purity of presence and construct a self-within-a-world. Cūḷasuññatā Sutta gives another perspective on this process.

The practitioner’s entry into emptiness is characterised by the “signless concentration of mind,” and in mature insight practice even this state is subject to investigation and deconstruction.

Again, Ānanda, a bhikkhu ... attends to the singleness dependent on the signless concentration of mind (animittaṃ cetosamādhiṃ His mind enters into that signless concentration of mind and acquires confidence, steadiness, and resolution.

He understands: “This signless concentration of mind is conditioned and volitionally produced (abhisaṃkhato abhisañcetayito).

But whatever is conditioned and volitionally produced is impermanent, subject to cessation (yaṃ ko pana kiñci abhisaṃkhataṃ abhisañcetayitaṃ tad aniccaṃ nirodhadhamman ti papānāti).”

When he knows (jānato) and sees (passato) this, his heart is liberated from the taint of sensual desire (kāmāsavā), from the taint of becoming (bhavāsavā), 10

and from the taint of delusion (avijjāsava). When it is liberated there comes the knowledge (ñāṇa), “It is liberated.” Even the signless concentration of mind is a construct; even that can be clung to; and even that must be abandoned.

Conclusion

We have examined the Buddha’s teaching on emptiness and have seen how it culminates in the radical simplicity of just-this! In the end, it is very simple.

What is absent is absent, and what is present is present, and practice consists of cultivating the clarity necessary to see this.

What is absent is what we assume is present - ourselves in our world.

The practice requires us to watch closely, not taking anything for granted, so we can cut through our projections as they occur.

These projections are always available, for we are doing them now; and so liberation is always available, for we can see through our projections now.

The seeing through is practice; what is seen through is understanding.

And these constitute the signless concentration of mind and the signless liberation of mind.

1. In his translation of Majjhima Nikāka, Bhikkhu Bodhi uses the term “voidness” to translate suññatā, instead of the more familiar “emptiness.”

However, in his later translation of Saṃyutta Nikāya he uses “emptiness.” I shall modify Bodhi’s translation here, and use “emptiness” throughout. 2.

See Paul Williams & Anthony Tribe. Buddhist thought. A complete introduction to the Indian tradition. London: Routledge, 2000: 131-152; and Andrew Skilton.

A concise history of Buddhism. Birmingham: Windhorse Publications, 1994: 99-102 & 115-119.

3. Bhikkhu Bodhi & Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoli (trans.). The middle length discourses of the Buddha.

A translation of the Majjhima Nikāya. 2nd edition. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2001: 1334 n.1150. 4. T. W. Rhys Davids & William Stede (editors). The Pali Text Society’s Pali-English dictionary. Oxford: Pali Text Society, 1998 reprint: 367.

5. Bodhi (2001): 1239 n. 449, here commenting on “the signless concentration of mind” discussed in Mahāvedalla Sutta (M43). See also Bhikkhu Bodhi (trans). The connected discourses of the Buddha. A translation of the Saṃyutta Nikāya. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000: 1445 n. 312.

6. Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s translation: “Thus he regards it as empty of whatever is not there. Whatever remains, he discerns as present: ‘There is this.’ And so this, his entry into emptiness, accords with actuality, is undistorted in meaning, & pure.” (http://www.accesstoinsight.org/canon/sutta/majjhima/mn121.html). 7. Bodhi (2000): 1163-64

8. See (M43) Mahāvedalla Sutta.

9. Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Emptiness. http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/modern/thanissaro/emptiness.html. (Revised 19-Oct-2003.) 10. For a discussion of aññaphala samādhi, see Bhikkhu Ñāṇananda. Concept and reality in early Buddhist thought. An essay on papañca and papañca-saññā-sankhā. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1971: 58-61. 11 </poem>