Buddhism : Naga, Nagas, Nagi

What looks like a dragon, smells like a dragon, and belches fire like a dragon? In Thailand, it’s a Naga, a mythical serpentine creature that has nothing to do with dragons. Dragons stem from Chinese culture. And while Thais have been infamous throughout history for knocking-off the work of others, they borrowed the Naga from India, not China. Though they didn’t let China’s fire-breathing creature go completely to waste. The Thai version, Tua Luong, started making its appearance just before the 19th century. But never caught on as well as the Naga, whose image is evident at every wat you’ll visit when touring the Kingdom.

The Thai people are known for assimilating their neighbors’ culture into their own. Cambodians seem to be the only ones who care, frequently calling foul in regard to religion, places of worship, and language. Unlike modern day pirating practices however, for culture it’s never been about copying, or stealing from the best to Thais, but rather taking a very Buddhist-like approach to the cultural invasion of other countries. Instead of going toe to toe and fighting outside influences, historically, Thais have melded those influences into their own. A peculiar tendency for such an xenophobic race.

This is the second post in my Buddhism 101 series, which has more to do with Buddhist-related images and the like that a typical touri might encounter on a visit to Thailand than it does the Buddhist religion itself. You can certainly enjoy a visit to the country and tour local wats without any knowledge about what you are seeing. Wats are pretty cool in their own right. A bit of info, however, can make your visit more rewarding. If nothing else, you can spout off your new found knowledge to your fellow travellers until they are sick of hearing you talk.

For me it’s never been a matter of a need to know as much as simple curiosity. Today’s lesson children, is a good example. I’ve run across Naga often enough, and at sometime in my journeys picked up the right word for the serpentine dragon-like images frequently used as balustrades and roof finials at Buddhist temples. Knowing the name and knowing what it identifies really is enough. Knowing the legends surrounding the Naga is icing on the cake.

My search for enlightenment (which sounds better than idle curiosity) began simply enough: I wanted to know if ‘nagas’ was the correct plural for naga. I’d already decided I liked nagi best, even if I’d be the only one ever using that word. Turns out nagas, what you’d expect, was the proper plural and now knowing that I could summarily dismiss conventional wisdom and stick to my own term: Nagi. Even though nagi is actually the word for a female naga. Huh. Wonder how you sex a snake? Well, there goes another half a day on Google . . .

Nagi are a common image throughout India and Asia, and play an important role in SE Asian mythology. In Malaysia they are a type of dragon with many heads; in Indonesia the Naga is a wealthy underworld deity; and in Laos they are beaked water serpents. Cambodia’s beliefs trump them all. According to Khmer legend, the Nagi were a reptilian race of beings who possessed a large kingdom. The Naga King’s daughter married an Indian Brahman, and from their union sprang the Cambodian people. Cambodians still say that they are “Born from the Naga” and seven-headed naga serpents are depicted at Khmer temples such as Angkor Wat.

Nagi also play an important role in at least one Western religion, whose followers refer to themselves as gamers. Outsiders call them nerds. In the World of Warcraft, the Naga are former Highborne night elves who mutated into vengeful humanoid sea serpents. Westeners looking for a more familiar story behind the Naga may relate it to the serpent in the Garden of Eden, a Christian myth. But in Thailand Nagi are not symbols of evil but instead play the role of protector, especially in regard to Buddha.

Like all of us, they have their bad side too, but even in the Thai version of the most well known bad Naga myth, the Mahabharata, they are viewed more as part of the balance between the sky and earth, rain and sunshine. Kind of a symbiotic relationship like yin and yang; a concept, which following local tradition, they borrowed from the Chinese.

The Naga were an integral part of the belief system of early Thais, predominately among those living in the North and Northeast portions of the country where the influence and moods of the mighty Mekong River could mean life or death.. At one time in this area, serpent cults were as common as they still are in India today. When Brahmanism spread into the region, the traditional Phaya Naga were assimilated into the new religion. Same same when Thervada Buddhism became the predominate religion.

Old legends about Nagi became part of the new religion’s body of myth. This melding of myth can be seen today at wats; Thai folk legend holds Nagi bring earth from river bottoms to build the temple bases. Carved Nagi flank stairways of the more important buildings, symbolizing the link that leads from earth to heaven. Devout Buddhists believe the Naga leads souls to nirvana on these magic ladders.

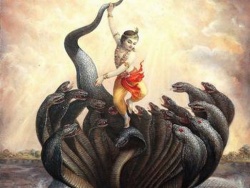

The story of Buddha features Naga throughout his life. Starting at birth. When crown prince Siddhartha was born, a multi-headed version of the Naga caused warm water to gush forth for baby prince’s first bath.

In Buddhist lore, the Naga is also associated with the final meditation by the Buddha as he strove to reach enlightenment. When the Earth Goddess, Thorani, wrung out her wet hair to drown the demon Mara and his army of tormentors, the Naga coiled itself under the Buddha to raise him above the flood waters, spreading the hoods of its seven heads to protect him from the rain. In the northern part of Thailand where belief in the Naga is predominant, the most popular statue to be worshiped depicts Buddha sitting on serpentine coils with a multi-headed form of Naga rising behind to form a shelter for the Buddha. Achitectural details in Thailand’s wats pay homage to several other Naga myths.

The most common, and most numerous Naga seen at a wat are the heads used as finials on temple roofs. Here they are often fanciful and usually turned up and facing away from the roof. Many are styled in flame-like motif. Some are designed to catch rain water flowing off the roof of the temple and shoot it out of the Naga’s mouth, a representation of the integral relationship between the serpentine creatures and water in Thai lore.

Nagi can live anywhere on earth but the Thai and Lao versions of the Naga generally live near or in water and their legend is a popular and sacred belief to Thai and Lao people living along the Mekong River. Many pay their respects to the river because they believe the Naga still rule it. Every year between 6 and 9 p.m. on the night of 15th day of 11th lunar month, an unusual phenomenon occurs along the Mekong River stretching over 20 kilometers between Pak-Ngeum and Pon Pisai districts in Nong Khai province that ties the myth of the Naga to the mighty Mekong. Red fireballs the size of eggs appear to rise from the river, shooting high into the nighttime sky from the deepest, Lao side of the Mekong.

In some years there are only a few; in 1999, almost 3,500 were seen. Local villagers believe that the Naga who live under the Mekong shoot the fireballs into the air to celebrate the end of Vassa, or Buddhist Lent. Both local Thais and Laotians claim this is a natural phenomenon, a reminder to them by the Naga to treat the waters with respect.

Their assertion that the Naga are responsible for the fiery display rests on an ancient Buddhist legend. During his final incarnation, the Buddha returned to earth after teaching his mother in heaven at the end of Buddhist Lent. The Nagi and his followers welcomed him back and showed their devotion by blowing fireballs into the sky.

This year’s display, and the accompanying festivities will occur on October 11 and 12, with the main festival being held at the City Pillar Shrine at Wat Thai in the Pon Pisai district.

Even if you don’t believe in the mythology or history of the Naga you can still appreciate the beauty they bring to Thailand, and now have ample info to bore your fellow travellers with.