Buddhism and the Philanthropy of Compassion

By Michael Nowik

Zen Buddhist Temple, Ann Arbor, Michigan

From a religious panel discussion, part of the “Philosophy of Philanthropy” course of the Ferris State University Master's in Education with a Concentration in Philanthropic Studies.

The Buddha

Buddhism, the world's fifth largest religion (360 million worldwide), is a non-deist belief system that was founded by a Nepali prince Siddhartha Gautama in approximately 528 BCE.

Within the context of philanthropy, as the love of humanity, the philanthropy of Buddhism could best be described as subjective rather than objective.

Although there are no well-known Buddhist philanthropic organizations, foundations or trusts, the thread of dana (generosity) connects Buddhist individuals and communities worldwide in a legacy of compassion and selflessness.

In this regard, the philanthropic “gifts” of the historic Buddha to the world include a detailed analysis of human suffering and a method of liberating humanity from that suffering.

Prince Siddhartha was born in approximately 563 BCE in the village of Lumbini, located on Indo-Nepal border, about 250 km southwest of Kathmandu, the capital of present day Nepal.

Both King Suddhodana and Queen Maya doted on their son and wished to protect him from any distress that could affect his happiness.

Legend has it that Siddhartha's parents confined him within the walls of the palace, sheltering him from all unpleasantness.

One day, Siddhartha disobeyed his parent's rule and left the palace with his charioteer Channa to experience the world outside of the palace grounds.

It was during this excursion that he encountered for the first time an old man, a very sick person, a corpse and finally a wandering ascetic, who despite his surroundings was said to have calm eyes and an expression of serene detachment.

Siddhartha had never been allowed to see the aged, the sick, or the dead, and as a result, these encounters troubled him deeply.

Returning to the palace, he experienced a profound personal and spiritual crisis.

How was it possible, he pondered, for he or anyone else to enjoy life when there seems to be no escape from suffering, misery, sadness, and ultimately personal extinction?

Rejecting his princely life of luxury and wealth, Siddhartha left the palace one night, never to return.

At the age of 29, he began his spiritual quest as an ascetic, searching for the supreme truth and for an answer for how to put an end to human suffering.

After six years of intense privation and self-mortification, he rejected the extremism and futility of the strict asceticism, which he had been following, as a method of attaining absolute truth.

Regaining his health once again, Siddhartha sat beneath a bodhi tree one day in deep meditation, determined not to leave until he attained supreme enlightenment. In the early hours of the morning of the full moon of May in 528 BCE, after a night of deep meditation, he attained enlightenment.

Soon, Siddhartha was recognized, by those whom he encountered, as a most extraordinary being. In denying that he was a god, a reincarnation of a god, or a wizard to all inquiries, people would persist and ask,

“So what are you?” Siddhartha would simply reply, “I am awake.” Buddha literally means “The Awakened One.” The Buddha died in approximately 483 BCE.

Dharma - The gifts

It is important to note that Siddhartha Gautama never intended to establish a new religion, and he never taught Buddhism.

All the Buddha ever sought was a way to relieve suffering, and all the Buddha ever taught was how to awaken.

Whether historic or symbolic, the aged, the sick and the dead that Siddhartha encountered, represent the common fate that awaits us all.

However, just as a Western cliché affirms that, “Knowledge is power”, a common Zen aphorism states, “Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional.”

The more we understand (about suffering), the less we suffer.

With his enlightenment beneath the bodhi tree, Buddha is said to have “set in motion the wheel of Dharma”.

Dharma may be defined as the truth, the teaching or the way.

Integral to the Dharma, and foundational to all Buddhist belief, are the “Four Noble Truths”:

Suffering is universal.

Suffering (as opposed to pain) exists because of our attachments, greed, and self-centeredness.

Our egocentrism, possessiveness and greed can, however, be understood, overcome and rooted out.

This rooting out can be accomplished by following a simple, reasonable Eightfold Path of behavior in thought, word and deed.

In setting forth the Four Noble Truths, the Buddha explained the essential character of suffering.

He then provided people with a method of liberation from their suffering, which is contained in the Eightfold Path.

In explaining these concepts to the people of his day, the Buddha spoke simply and plainly in “language of the valley”, often using metaphor.

He submitted that all of humanity was “sick”, and that he was offering his services as a compassionate physician.

If the Four Noble Truths were his diagnosis of the suffering that afflicted the world, then the Eightfold Path was the remedy or cure.

The Eightfold Path:

Right Understanding - Understand that the world is conditional and impermanent.

Right Intention - Remember that, “You are what you think”.

Right Speech - Speak honestly, compassionately and well of others.

Right Action - Behave selflessly, constructively and harmlessly to all living things.

Right Livelihood - Choose a livelihood that enables you to follow the Way.

Right Effort - Use discipline and control to overcome difficulties.

Right Mindfulness - Be present in the moment.

Right Concentration - Develop the focused state found in meditation - one-pointed and calm.

The Anglo-Irish historian and philosopher Gerald Heard (1889 - 1971) paraphrased the Eight Steps in the format of a treatment or a rehabilitation:

First, you must see what is wrong.

Next, you must decide that you want to be cured.

You must act and speak so to aim at being cured.

Your livelihood must not conflict with your therapy.

That therapy must go forward at the “staying speed” that is, the critical velocity that can be sustained.

You must think about it incessantly and learn how to contemplate with the deep mind.

The Bodhisattva Ideal

Shortly after the Buddha's death, a division occurred among his followers with the emergence of a new school of Buddhism known as Mahayana, or the “Greater Vehicle”.

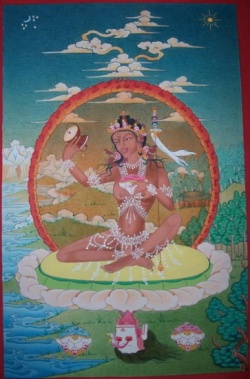

Rejecting the Therevadan emphasis on monastic life and the attainment of individual arahantship (sainthood) as restrictive and self centered, Mahayanists emphasized the concept of the Bodhisattva (being of wisdom).

A Bodhisattva may be described as a “Buddha-in-waiting”, one having reached the goal of nirvana postpones his or her own release from the world and reincarnates again and again for the sake of others.

A Bodhisattva's only goal is to win enlightenment, not for herself or himself, but for the benefit of all sentient being.

To achieve this, the Bodhisattva must acquire six perfections (Paramitas) - those of generosity, virtue, patience, perseverance, meditation and wisdom.

In the Zen Buddhist Temple of Ann Arbor Michigan, as is Mahayana temples and homes throughout the world this goal is expressed daily with the individual and collective chanting of the Bodhisattva Vow:

All beings, one body

I vow to liberate.

Blind passions, one root

I vow to terminate.

Dharma Gates, one mind

I vow to penetrate.

The Great Way of Buddha

I vow to realize.

In the words of the Dalai Lama: “The essence of the Mahayana school is compassion.

In Mahayana Buddhism you sacrifice yourself in order to attain salvation for the sake of other beings.”

It is this foundational element of compassion that captures the essence of Buddhist philanthropy - a compassion that compelled the Buddha first, to explore, in depth, the causes of human suffering and then offer a method of liberation from that suffering.