Buddhism has one of the richest textual traditions of any world religion. While many Buddhist teachings implore us to look beyond our language and concepts, the written word and awakening have been closely connected since the earliest days of the dharma. The British Library recently opened a major new exhibition—simply called Buddhism—that explores this important relationship between textuality and spirituality with a collection that spans around 20 countries and 2,000 years.

“We have designed the exhibit with everyone in mind,” said lead curator Jana Igunma. “We wanted to display the diversity of Buddhist art and, at the same time, show the strong continuity of the life of the Buddha and his teachings in scripture.” Accompanying the library’s largest-ever display of Buddhist treasures will be a series of meditation classes and lectures on Buddhist art history, music, dance, ethics, the contributions of women, calligraphy, and more. The events program will conclude with a two-day international conference on translation, transmission, and the preservation of Buddhist texts and practices from February 7–8, 2020. Buddhism runs through February 23.

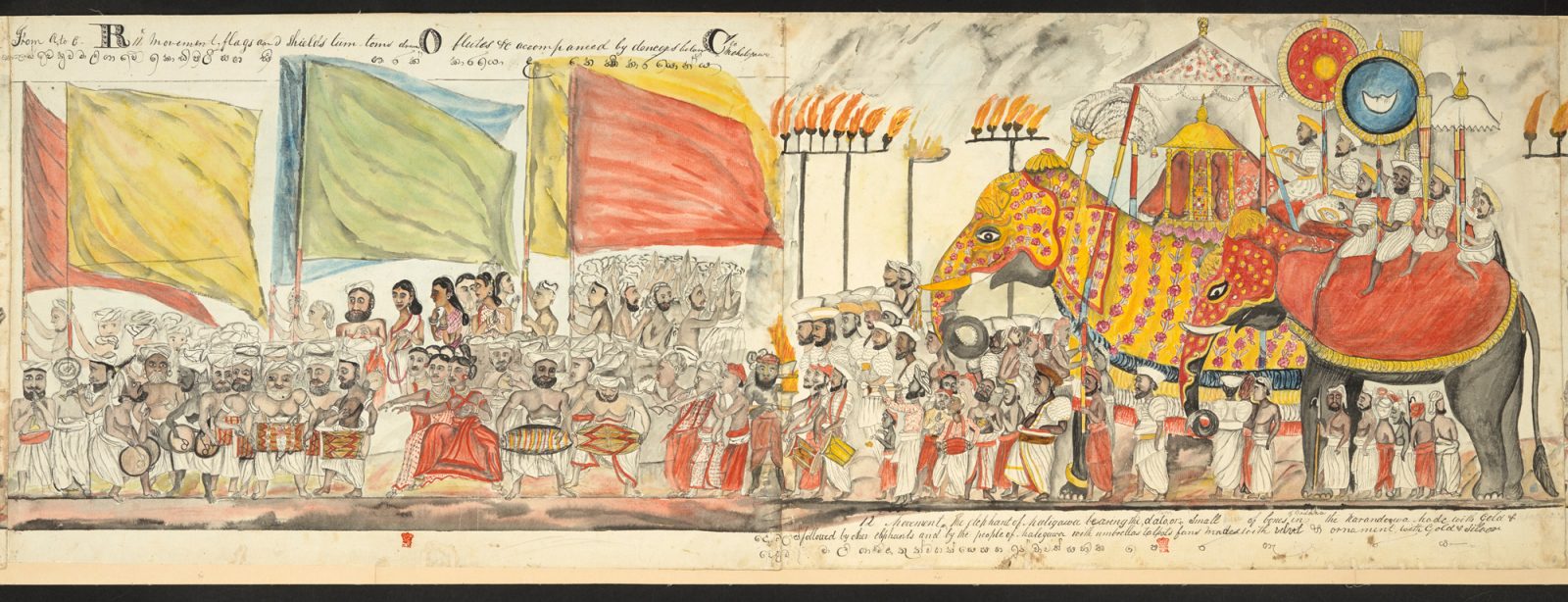

The exhibition begins by recounting the life of the Buddha and his past lives through scripture, sculpture, scroll paintings, and votive objects. From his enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree and first sermon at Deer Park to his passing away (mahaparinirvana) and the distribution of his relics, viewers will gain a fuller picture of how the Buddha’s long career was artistically represented and understood within and outside the Buddhist world. We see the Buddha’s miraculous birth at Lumbini Grove in a woodblock print from Eastern Tibet, his encounter with the four sights (Siddhartha Gautama’s first inspiration to end suffering: an elderly man, a sick man, a deceased man, and an ascetic) in a hand-painted Chinese book, his renunciation of royal privilege and family life in a 7.6-meter-long Burmese accordion-style codex, and his temptation by the demon Mara is depicted in vivid colors in a Nepalese translation of the Lalitavistara Sutra.

Nearby is a 15th-century copy of the book Barlaam and Josaphat, a Christian romance inspired by the life of the Buddha, opened to a page with an engraving of Josaphat, the Christianized Prince Siddhartha (whose name is derived from the Sanskrit word for bodhisattva), giving up his worldly life. Printed in Germany around 1470, this story was the Middle Ages’ equivalent of a bestseller, and it saw many translations, including Arabic, Georgian, Hebrew, Slavic, and Ethiopic versions.

European encounters with Buddhism are not the main focus, but there are traces of British patronage and power throughout the exhibition. This is intentional, and part of a wider effort of British institutions to confront their colonial histories and explore alternative ways of exhibiting Asian objects, many of which were stolen or otherwise procured during the country’s imperial expansion.

A contemporary Thai-style thangka painting, for example, depicts traditional scenes from the Vessantara Jataka, one of the Buddha’s birth tales in which he perfected generosity. Occupying the typical place for donors on the composition are William Shakespeare and English officials—a playful and somewhat satirical nod to the British Library, which commissioned the piece in 2019.

For many, the stories in these illuminated scriptures may raise the question of whether the Buddha was a historical or purely mythical figure. While interesting, this question “is not the best way to approach the exhibit or the tradition itself,” explained Vishvapani Blomfield, an author and Triratna Buddhist meditation teacher, during his inaugural lecture at the library on October 25. Instead, he argued, viewers should use their imagination to “enter the mental world that these texts evoke and describe, so we can come closer to seeing them in their full context.”

Some of the more remarkable texts invite us to stretch our imagination back to the early centuries CE. A collection of 2,000-year-old birch bark scroll fragments contain texts from the Tripitaka (the “three baskets” comprising the Theravada Buddhist canon) and are among the oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts in the world. It was discovered inside a clay water vessel in the historical region of Gandhara (located in modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan), which was a vibrant center of cultural exchange on the Silk Road that enabled Buddhism to spread from India to East Asia. Other fragments from the Buddhist canon in the exhibit date back to the 5th century. Written in Pyu script and hammered onto gold sheets, extracts from the Vinaya Pitaka, excavated in Burma in the late 1890s, spell out rules of discipline for Theravadan monastics.

Another emphasis in the collection is how the spread of Buddhist ideas and value systems across Asia impacted the development of new writing and printing techniques. The Hyakumanto Dharani, or “One Million Pagoda Dharani [a chant or incantation]” commissioned in the late 760s under Japanese Empress Shotoku, is one of the oldest existing examples of printing in Japan (and in the world). Likewise, the illustrated palm leaf Pancharaksha, a ritual text on the Five Protectors from 12th-century Nepal, testifies to the printing technologies being developed in the medieval period. There is even a station where you can touch some of the materials commonly used in manuscript production, such as palm leaves, mulberry paper, and silk. Made from paper, wood, cloth, mother of pearl, ivory, or gold, the 120 illuminated texts are exceptionally varied, but the care put into each work binds them.

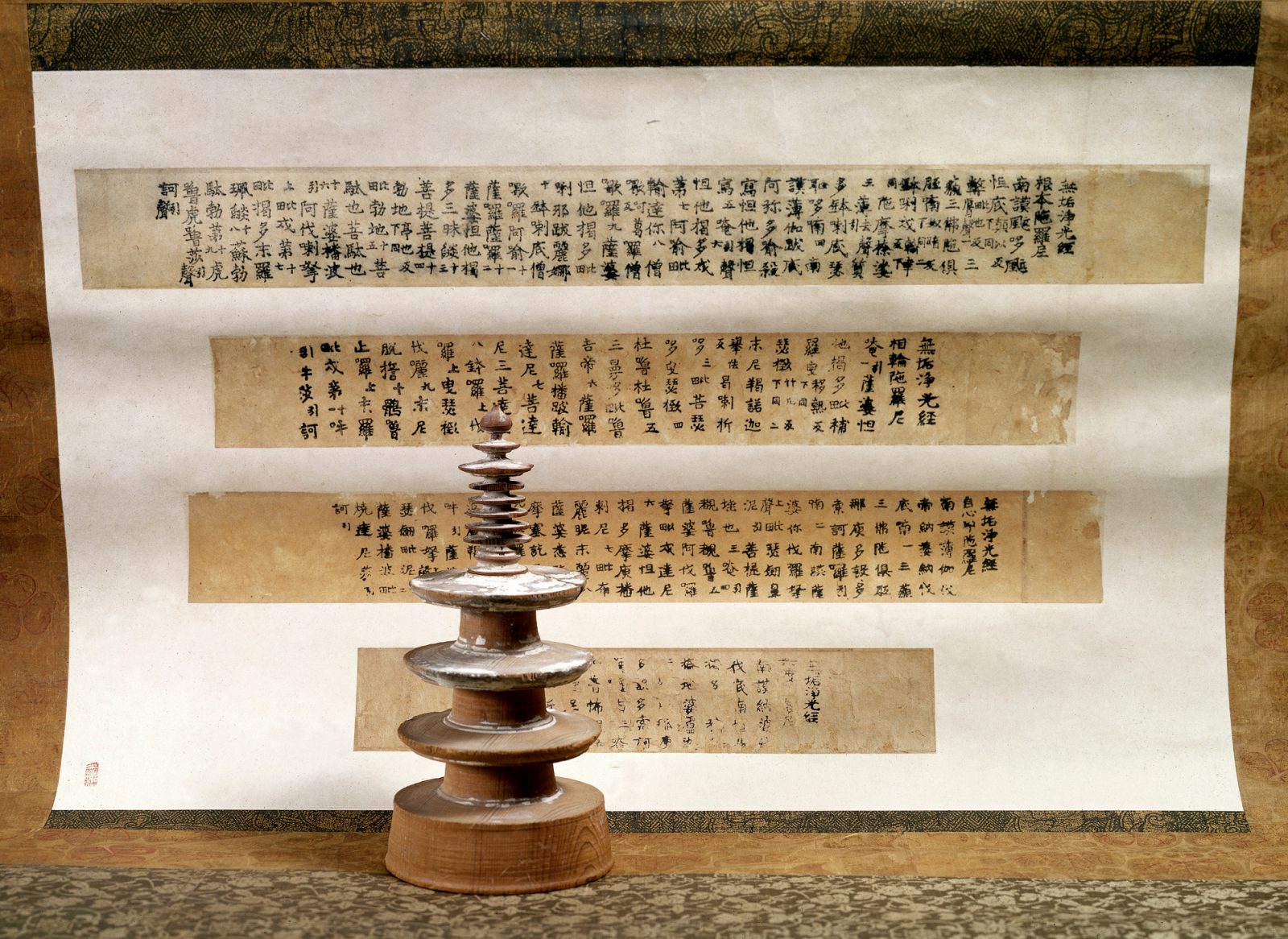

Other works, like the Jataka Tales from Southeast Asia, are filled with folk wisdom and lessons about virtuous qualities. The collection also contains rare copies of the Lotus Sutra found in caves near Dunhuang, China, and various translations of the Diamond Sutra from China, Tibet, and Korea—key Mahayana sutras that convey cornerstone philosophical tenets, including Buddhist teachings on non-attachment and emptiness.

Despite the exhibition’s heavy focus on text, Buddhism is not all about doctrine. It has flourished over the millennia through the living practices of its devotees, and the final section of the gallery contextualizes this idea. Copying the words of the Buddha was and still is considered a highly meritorious act. Memorizing, chanting, and listening to the recitation of sutras remains a significant part of ritual life for monastic and lay communities worldwide. The library further encourages an experiential understanding of the displayed works through an accompanying soundscape, an ambient blend of birdsong, flowing water, and gongs.

Just before leaving, viewers will pass three short films by Hong Kong-based visual artist Stanley Wong that bring to life a popular passage from the Heart Sutra, one of the many sutras found in a body of literature known as the Prajnaparamita, or Perfection of Wisdom. With a calligraphy brush and wet ink, the artist paints the words form is emptiness, emptiness is form in large Chinese characters on paved ground. Once etched, the inscription quickly fades away.

The same principle can be applied to the words of the Buddha. Scripture from antiquity to the present may be preserved in libraries and museums, but, as the Buddhism exhibition makes clear through its collection, the enduring resonance of the Buddha’s teachings comes from the way they are rewritten into people’s lives in each and every era.

♦

Buddhism is on display at the British Library through February 23, 2020. Tickets for the exhibition and events program can be purchased here: www.bl.uk

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.