Buddhism in Australia - Story by Sophie Cunningham

A shorter version of this article first appeared in 'Saturday Extra', The Age, May 18 2002.

Jenny Kee was raised as an Anglican. As a teenager, however, she drifted away from the church and from faith. By her mid-20s she was a famous fashion designer; in her late 20s she married and had a child. It was a good life. Then, in 1977, Kee and her baby daughter Grace were travelling from the Blue Mountains to Sydney when their train was crushed under a falling bridge at Granville. Eighty-three people died many of them in the same carriage as Kee and Grace. For the first time, Kee felt that in order to recover she had to find something bigger than herself.

Christianity didn't feel like the answer. Instead, she tried meditation; she tried Siddha Yoga, a variant of Hinduism. In 1986 she went to Thailand to work with Thai weavers and met a Buddhist monk, Ajahn Pongsuk. The monk, whose work fighting the destruction of forests has been recognized by global environmentalists such as David Attenborough and Friends of the Earth, told Kee "that the house we live in is our second home; our first home is the forest.

"If one has a spiritual awakening I had it in the bush, says Kee. "I came back from Thailand in 1986 and became a raging environmentalist. She became an activist, travelling to Jabiluka to protest against uranium mining. She was arrested in protest against logging in the South East Forest in New South Wales. In Kee's mind, environmentalism and Buddhism were the same. In 1997 Kee and her partner Danton Hughes restored a dairy farmer's cottage in the Blue Mountains. The beautiful house looks across the mountains, the regenerating bush and a sea of waratahs. The home and the garden testify to Hughes' craftsmanship, and the love he and Kee shared. And it was here a year ago that Hughes, who suffered from depression, committed suicide.

In the horrific time after his death, Kee's absorption in Buddhism intensified, becoming a daylong, lifelong commitment. She read The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying and found a "profound wisdom in it. She has been left with an intense desire to understand the meaning of suffering and to transform it.

"The personal picture is me, in a house, with a body, she says of her loss. "And then there is the bigger picture. She nods towards a large window of her house in which the sun is setting, turning the bush a dark blue and the sky gold.

"The pain of his death was like an explosion, she says. "That pain opens your heart; shock does that to you. . . You ask me what bought me to Buddhism? Suffering. Suffering and great pain.If Kee's personal story is extraordinary, her turn towards Buddhism is not. Australia today has 348 organizations that describe themselves as Buddhist, more than twice as many as in 1995. The Dalai Lama's book, The Art of Happiness, has sold more than 150,000 copies in Australia and is among a series of Buddhist bestsellers in Western countries. They include A Path With Heart by American Buddhist Jack Kornfield and The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying - whose author, Sogyal Rinpoche, spoke on business ethics to a seminar organized by Sydney's Commonwealth Bank. Buddhism also has a huge presence on the Internet, including the world's most visited Buddhist website, www.buddhaNet.org, run from a Sydney office by Australian born Thai Buddhist monk, Venerable Pannyavaro.

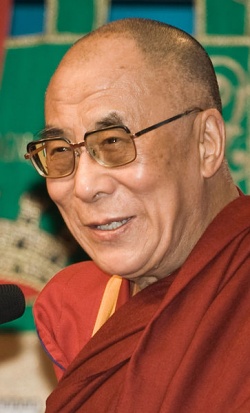

And from tomorrow, for four days, the Dalai Lama is speaking at the Tennis Centre. The crowds are certain to be large: when he spoke there in 1992 the audience was the largest he had ever attracted in a Western country. Thirty thousand people turned up, but some 10,000 had to be turned away. The organizer of that tour, business man George Farley, talked to me of his amazement when he realized that the traffic jam holding up the car in which he was driving with His Holiness' Secretary, Tenzin Geyche, to the Tennis Centre was caused by people trying to get there. "Where are all these people going?" he asked. "To see His Holiness" I said.

But what does Buddhism's popularity mean? Does it reflect deeper shifts in the state of spirituality and religion? Or are most of the people who will go to the Tennis Centre, and thousands of others, gripped by the latest fashion in the money-rich, soul-poor West?

"You better hope you don't come back as a whale in your next life, warns a recent Greenpeace advertisement. And blazing across a New Idea cover last month: Bizarre New Life. Brad and Jen quit holiday for Buddhist hideaway. You can find signs of Buddhism's cultural presence everywhere. And yet the numbers of converts are more modest. In the 1996 census 199,000 people described themselves as Buddhists, a leap of 59,000 people from the last census. That made Buddhism Australia's second fastest-growing religion, after Hinduism, but most of the devotees are immigrants from Indochina, Taiwan and Sri Lanka. About 10,000 Buddhists were converts from western backgrounds, compared to the 50,000 Vietnamese Buddhists who live in Melbourne alone.

"People grossly overestimate Buddhism's western numbers, says Professor Gary Bouma, a Monash University sociology professor and Anglican minister. Bouma thinks many more people profess vague allegiance to the ideals of Buddhism than are card-carrying members. Buddhism, he adds, "is the religion to have when you're not having a religion. Similarly, Greg Bailey, a Reader in Sanskrit at Latrobe University, thinks the allure of Tibetan Buddhism is fuelled by western fascination with the exotic. The Dalai Lamae says, "is promoting a particular image of Buddhism popular with the middle classes. But the Reverend Philip Hughes of the Christian Research Association has a different view. He thinks the census figures don't reflect Buddhism's influence: how it has managed to both reflect and benefit from a fundamental shift in western attitudes to spirituality.

Hughes observes a huge growth in spiritual experiment in Australia. Churches are experiencing a churn effect: 38 per cent of worshippers between 1991 and 1996 were newcomers, while 33 per cent of previous worshippers left the church in that period, according to the 1996 census. And half of all people who put `No religion' on the census form said that spirituality mattered to them.

It's a climate tailor-made for Buddhism, says Hughes. Unlike Christianity, Buddhism in the West doesn't ask followers to make a lifelong and exclusive commitment, or to join a community of believers. "People will do a meditation course for three or four weeks, read some books or go to a forum, he says. "They will do something as long as they see it might have benefits for them. They don't necessarily want the full Buddhist picture of the world and a lot of Buddhist teachers are not requiring that.

The key, perhaps, is meditation, which is not exclusive to but is strongly associated with Buddhism. A 1998 survey of 8500 Australians by Hughes' association and Edith Cowan University in Perth found that 10 per cent of the group had practiced Eastern meditation -"about the same number as you'd find in church on any particular Sunday, says Hughes.

The changes are reshaping the church, too. The long dormant tradition of meditation in Christianity is being revived through church-based meditation groups. Bouma says that has nothing to do with Buddhism; rather, it reflects "the cultural drift towards experiential religion, the pursuit of transcendence within. But Hughes thinks, "Buddhism has opened us (Christians) to different possibilities, and to parts of our tradition that we have forgotten.It is 8pm on a Friday and at the Tara Institute in Mavis Avenue, East Brighton, the Tibetan Lama Venerable Geshe Doga is about to give a teaching. Tara, one of Melbourne's largest Western Buddhist centres, is housed in an old Brighton mansion. Beside the house is a gompa, or temple, a building that was once a Catholic chapel.

A crowd of about 80 sits cross-legged on maroon cushions as the lama leads prayers and a haunting, monotone chant. Those who don't know the words rock silently. It's a stirring moment but the lecture that follows is harder going. Although the lama has quick, expressive hands and an encouraging smile his lecture is hardcore Buddhist metaphysics on the nature of the mind. And it's in Tibetan. His translator, a wry German-born monk called Venerable Fedor, cracks the odd deadpan joke.

Western Buddhism in Melbourne is dominated by the Tibetan school. (Zen, which has had such an influence on American Buddhism, shaping the writings of Jack Kerouac and Alan Ginsberg among others, has never been strong here.) The reasons go back to 1959, when China's invasion of Tibet sent a generation of brilliant Buddhist teachers - notably the Dalai Lama - into exile in India and the West. But in the early Seventies a young man, Dr Nick Ribush, who had worked for several years at the Royal Melbourne Hospital's renal unit Brisbane, went to travel the world. He got as far as Kopan Monastery, in Nepal.

'The 1972 course was when Nick Ribush turned up. Nick was sending letters back to Australia saying "you've got to get into this" and friends started getting really worried, saying, "Nick's flipped". He was sending these twenty page letters in '73. Twenty people came over. This created an incredible raft and explains the strength Melbourne has over a lot of other cities in the world,' says Adele Hulse, a member of Tara Institute, and a practising Buddhist since Ribush's time.

In 1974 Nick took ordination, and went on to set up the Buddhist publishing house Wisdom Publications. He disrobed some years ago, but remains devout, not dismissing the possibility that he might become a monk again. He still works for the Dharma, out of Boston. Even though we only spoke by email and the phone his warmth and compassion was extraordinary. To talk to Nick is to talk to a man who has left his former self along way behind. Like many of the people I spoke to, the trigger for their initial interest in Buddhism seems so long ago to them as to be irrelevant. Perhaps Buddhist teachings about living in the present has fundamentally changed their relationship to their past. Nick Ribush could not bear to retell his story, and instead sent me a wad of articles instead with gee-whiz headlines such as 'The Merry Monk' and 'Trendy doctor found peace in a cave'. In 1979, one of these article quoted him as saying working with victim's of drug dependency in hospitals was one of the things that led to his exploration of Buddhism. 'I came to the conclusion that people preferred temporary happiness to physical health and were prepared to destroy themselves in its pursuit.' Over the years he has run seminars, including one called 'Kick the Habit,' for people with addiction problems. 'The young seek solace in drugs from boredom,' he says. 'Older people try to tranquillise themselves from tension. The basic problem is dissatisfaction.'

Every week Tara holds meditation nights, study groups and more formal teachings. It has about 200 regular members but every week twice as many visitors attend casually to hear teachings or take meditation classes. While the number of members has remained steady in recent years, this second group has grown dramatically.

Many of the casual visitors are young people, says Kate Danford-Storey, who used to help organize the centre's meditation classes. "They come once or twice to try it out. A lot of people are not interested in Buddhism but meditation and then they find out about Buddhism secondarily."

As with Kee, a traumatic event triggered Danford-Storey's involvement in Buddhism. At 19 she worked at a suburban bank that was robbed by an armed gunman. Although the experience was awful at the time, Danford-Storey now calls it the best thing that ever happened to her. "It was a catalyst for me to stop what I was doing and become a better person. It was the Dalai Lama's non-violence that attracted me. Having had violence inflicted on me I never wanted to inflict it on others. It is one of the most crippling things that can happen to a person.

Jenny and Kate's experiences capture the delicacy of the west's embrace of Buddhism. It's precarious but profound teetering between the pain that is a part of the human condition and the desire to move beyond that to a wiser, more compassionate life.Russell French, a 25-year old electrician, had a more everyday introduction to Buddhism. He went to an all-male Catholic school and as a boy saw himself as a Christian. But in his teens he found himself struggling against elements of his religion. "Guilt and damnation, they really bothered me. If you didn't do certain things you were eternally damned in hell.

French gave up Christianity but not his spiritual search; eventually he came to Buddhism. He visits Tara occasionally and finds that meditation calms him, though he admits his commitment has slipped lately because it is so hard to keep up. He is also experimenting with Bhakti yoga, a form of Hinduism. "I'm still searching for something that is holistic and practical, he says. "Something I can combine with my dreams and ambitions. He finds Buddhism "accessible and practical. Themes like compassion you can easily incorporate into your life. Christianity, on the other hand, "seems like a dying religion to me.

French's words about Buddhism, of course, could also be applied to Christianity, especially the emphasis on compassion. The Dalai Lama himself, during a Christian-Buddhist dialogue held in Britain in the early `90s, said that Christianity, as the foundation of western culture, might be a more natural path for westerners to follow than an eastern philosophy such as Buddhism.

But Buddhism's appeal stems partly from this very refusal to be evangelical or exclusive. And in a time of suspicion of institutionalized religion, Buddhism is neither dominated by institutions nor is it a religion. It is a philosophy, a way of being in the world.

Tibetan Buddhism does demand adherence to certain behaviour: no killing of any living thing, no intoxicants, no bad speech and so on. But the basic tenet of Buddhism is not belief in a religious meta-narrative but the practice of meditation, or mindfulness. This does not require a leap of faith but discipline. When asked if Buddhism works the Vietnamese monk and best-selling author Thich Nat Hahn says merely: try it; follow the rise and fall of your breath and see how quickly the mind changes.

Adele Hulse relates her opening to Buddhism: "When I first met Lama Yeshe (her guru) my father had just died. Lama Yeshe said, What is born must die'. I said,I don't believe this stuff', and he said, `you don't have to believe. In Buddhism you don't need belief and you don't need faith. You need intelligence and understanding.

Elizabeth Weiss, a Sydney book publisher and Tibetan Buddhist, says the flexibility of Buddhist thought appeals to younger people because it resembles much contemporary philosophy. "The Buddhist notion of emptiness fits in with post-modernism because it argues there is no essential truth. The Buddhist idea of interdependence of all things fits with our understanding with modern physics.'

Buddhism's peaceful image seems embodied in the Dalai Lama. His "humanity, level-headedness and humour have had "an enormous impact on the world, whether you are a Buddhist or not. says Vicki Mackenzie, a journalist and author of Why Buddhism. Professor Carl Wood, the IVF pioneer, remembers taking the Dalai Lama on a tour of the Monash IVF program. "He wanted to know about IVF. It took an hour and a half and all the time his hands were going up and down. As Wood tells it the Dalai Lama was literally weighing up the issue. Finally Wood asked: "what's your verdict on IVF? "He said: There's good and bad in it.' Then he played around a bit, putting his hands in the air.A little more good than bad.' Wood says the Dalai Lama "was the first religious leader to say anything good about IVF.

At the time Wood had no involvement with Buddhism but while sick with cancer two years ago, he decided to learn how to meditate. Meditation not only helped Wood's battle with cancer, but provoked an appreciation of Buddhism. "I liked its principles and its teachings, he says; its "acceptance of others' difference.

People often approach Buddhism after some life crisis: sickness, a failed marriage, and some overwhelming anxiety. An even more common starting point is a wish to reduce stress through meditation. The end of a long relationship, and the consequent anxiety and despair, drove Peter Kelly, a warm and open man in his `70s, "into the arms of the Buddhists. "I found, and still find, the whole practice of meditation a wonderful way of providing a core of tranquillity.

As a teen Erica Wagner, now 39 and working in publishing, read some books with Eastern themes, notably Hermann Hesse's Siddhartha. When her children were young she tried yoga and meditation. But her interest only quickened when she went through the agony of a marriage breakdown. A psychologist who was a Buddhist lent her books: in one, The Miracle of Mindfulness, Thich Nat Hahn writes about the joy that can be found in making a cup of tea, as long as the mind is only focussed on that experience. "I just read that one chapter and I knew I could be happy, says Wagner.

Wagner is attracted to Buddhism because "I spend so much time working, so I try to apply this idea of `everything is just going to happen' to my life. I like the down-to-earthness of it. If I feel myself panicking, I can, with discipline, calm myself down. It could be argued that increasing interest in Buddhism over the last thirty years or so reflects wider cultural shifts and an attempt to address some of the ethical dilemmas confronting our culture, dilemma's caused by, among other things, over-population and Capitalism. "I've always thought that is really why communism was so successful, because it appeals to the spiritual hunger in people. It's such a good idea. The Dalai Lama was on record as saying in the 1950s that he saw strong parallels between communism and Buddhism," says Farley.

Simone Ford, a 31-year-old editor at Pan Macmillan who is interested in, but does not practise Buddhism says, "I wasn't looking for something greater in my life, but I recognized something in Buddhism that was akin to how I wanted to live my life. Being kind to other people, respect for animals, not consumerist."

Professor Lindsay Falvey, a Professor of Agriculture at Melbourne University puts it this way, "Buddhism talks about the development of agriculture as the beginning of amoral behaviour. It creates hording and attempts to corner the market and all the ensuing distribution problems. We have more than enough food [in this world) you just can't get your hands on it if you live in the wrong place."

It is easy to spot the similarities between Buddhism and counter-culture philosophies. Indeed, along with aspects of other Eastern religions, Buddhism was the inspiration for many of them. Buddhism has been incorporating ideas about compassion and social change into a daily way of life for thousands of years. Most of the people I spoke to who had been involved in Buddhism since the Seventies had been embroiled in the politics of that time.

Sandy McCutcheon, of Radio National's Australia Talks Back, ran illusion farm in Tasmania, as a Buddhist retreat during the Seventies. In many ways it was a simple extension of the notion of social activism and communal living. At the time of his conversion he worked in that hot bed of alternative living and socialism that was 2JJ (the forerunner of ABC Radio's JJJ).

"I was doing what a lot of people did in the late sixties and seventies - spiritual supermarket shopping. . . I did an interview with Anne McNeil, a Tibetan nun. Something happening in that interview. She said enlightenment was achievable within a single lifetime. And I had my moment. My Saul on the road to Damascus experience."

A few weeks later Sandy went back to Tasmania and built a gompa (temple) on his farm. "We ran this place to create the conditions where others could come if they wanted to. We had everyone imaginable- the mentally ill, people with problems with drugs and alcohol, prostitutes from the Cross. We ran it without ever talking about Buddha dharma. If they wanted to wander over to the gompa and listen to the teachings they could. Three thousand five hundred people went through the place."

Today it could be argued that younger people who have become involved in Buddhism have something in common with a growing political force, the Greens, not that either group would necessarily welcome the comparison. At 31, Peter Michelson has been a Buddhist and member of the Brunswick-based Friends of the Western Buddhist Order for 13 years. For the past year he has run a company called Coffee on the Run and is committed to running a business which is good place to work and practice, as well as sourcing ethical products - in this case coffee grown by growers who are light on the chemicals and have good employment practices.

"There is a lot of emphasis on working together. Communication is a big part of it. Trying to be as honest and direct as you can. Being open to feedback. Do you go for profit or do you go for customer service? I'm more into customer service and doing the job well and I figure that way the money will come anyway."

It's a long way from mysticism and mind-altered states. So, too, is the work of Dick Jeffrey, a former TAFE teacher and member of Tara Institute. Jeffries is the director of the Maitreya Project's Universal Education School in Bodhgaya, India _ the place in north India where Buddha is said to have found enlightenment. He spends several months a year in Bodgahaya, helping develop a school for children. The students work through the day, usually in the fields, but after days that often reach 50 degrees they come to school in the relative cool of the evening. It is their only chance of an education.

Falvey believes there is a different moral base between politics and Buddhism, arguing that political movements are single-minded in their attempts to achieve particular outcomes. "Buddhism is based on central teachings of conditionality and interdependence. Everything is effected by and affects everything else. Karma is the simplest expression of that. A green perspective is more absolute."

Falvey also makes the broader point that the renewed interest in Buddhism has coincided with political shifts, particularly identified with the Keating era, to orientate Australia away from Europe and towards Asia. Certainly history has played a part in all this, and Buddhism's popularity has been spreading rapidly in the West since the Chinese invaded Tibet in 1959 and drove many Buddhist practitioners out of that country and around the world.

Adele Hulse elaborates on this: "There were ten lamas who were the main exponents of Tibetan Buddhism to Westerners. Seven of them were deeply conservative, didn't speak English and used translators. Protecting and maintaining the lineage was their job. But three of them were wild cards. Sogyal Rinpoche is one of those wildcards. Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche who died in Naropa Institute in Boulder, he was another one of those wild cards. Lama Yeshe is the third wild card."To the committed, Buddhism is often a modest proposal: to respect other living things, to practice small acts of compassion, to seek to be happy. A Buddhist proverb says that the unenlightened man gets up in the morning, goes into the field, hews the wood and draws the water. The enlightened man . . . does exactly the same. Except he does it mindful of living in the moment, of every thought and action. It's the simple thing, so hard to do.

Falvey doesn't think Buddhism will have a big impact on Australian culture. Nor, for similar reasons, does Michelson. He acknowledges that while thousands of people come through the doors of the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order in Brunswick, many don't come again. "To live up to Buddhism's ideals is very hard, he says. "To actually bring it about takes all of your energy.

Some argue that more casual relationships with Buddhism, which is as deep as many enthusiasts go, are not enough to produce an authentic western movement. In Boomer Buddhism, a tough piece published on the website salon.com last year, American professor of religion Stephen Prothero argued that in its worst incarnations, Buddhism was being harnessed to achieve those old-fashioned American goals of power, personal autonomy and profit. He cited the advent of Buddhist gift shops and books such as Zen and the Art of Screenwriting, Zen Sex, Zen and the Art of Poker. "Instead of preserving Buddhism, Americans seem intent on co-opting and commercializing it, dissolving a religion deeply suspicious of the self into an engine of self-absorption.

Precisely because it is so easygoing and tolerant Buddhism can be seen as just another New Age philosophy. "The unfortunate co-incidence of the human potential movement and the rise of Buddhism in the West have made some people think Buddhism is the best way to ensure personal empowerment in all situations, says Rachael Kohn, presenter of Radio National's The Spirit of Things. "All traditions can be subverted by venal self-interest and Buddhism is no exception.

Is Buddhism transforming the West, or is the West transforming Buddhism? Peter Kelly agrees that because Buddhism focuses so much on the mind, its bad habits and how to change them, the philosophy is vulnerable to being used as therapy. "I think there are analogies between the process of psychotherapy and the path of self-realization in Buddhism. But there is a danger. The Buddhist focus on developing generosity and compassion is about something other than just solving inner conflicts that come from childhood.

But Buddhism-as-therapy doesn't really worry Adele Hulse. "Better people prop themselves up than fall over, she says with a shrug. "It's a beginning.

The Dalai Lama has been quoted as saying people should practise the religion of the culture we are born into. For a lot of us that means Christianity. While Professor Bouma believes says there is relatively little dialogue between Christianity and Buddhism, he believes more talking is done at a Grass Roots level, and within particular communities, such as the Vietnamese community. "In a Vietnamese family people will frequently say there are Catholic and Buddhist, which is interesting."

"In Braybrook, Victoria, the Head of the United Vietnamese Congregation, Venerable Thich Phuoc Tan and Minister Dean Eland from the Uniting Church's Sunshine Mission are doing a lot of talking. "We don't talk much about our different religious traditions but we realize we have a lot of similarities," Reverend Eland told me. "We talk a lot about the drop out rate of young people from our respective religious traditions. We are all dealing with a pluralism of community and I've been encouraging different faith groups to work together to build a sense of community." At one time Braybrook was described as one of Victoria's most disadvantaged suburbs. "That has changed in the last 2-3 years." Reverend Eland told me.

Venerable Thich's temple is a jumbled assortment of temporary buildings and more traditional temples. He has run it since 1996 and looks not unlike the laughing Buddha in the shrine at the front of the temple, though when I talk to him about his workload the smile disappears.

The story of his temple reflects the shift that has taken place, at least in Buddhism among refugee cultures, between how the religion operated in its country of origin and how it operates in Australia. "The nature of the Buddhist temple in Australia has changed enormously. I think about 30% religious [work] and 70% education and community," Venerable Thich told me. "The role of the monk in Australia has also changed. In Vietnam the monks do not engage in too much day-to-day activity. In Australia the expectation somehow has reversed. We are more socially engaged."

Reverend Dean Eland elaborates. "It is in the early stages for the Buddhist community and they are overwhelmed by demand on their services. We've been working with them to help them access resources in the community. For example, the Braybrook community centre provides training for starting community projects and community leaders. We have established a municipal advisory committee on projects and building."

The United Vietnamese Congregation of Victoria was established in 1980, but moved from Richmond, to Footscray, then Sunshine before the funds were raised to buy land in Braybrook. This story of moving from house to house while getting the money together to buy land is a common one.

Venerable Thich Quang Ba from Canberra explains the long and tortuous process of setting up a temple. "We start in a very small way. Rent a house, buy a house, neighbours complain, there will be some court case. It takes many years for someone to collect sufficient funds to buy a block of land, and many more years to build. Some hardworking monks have to create fundraising ways. Some dinner, some concert, some raffles."

There are approximately 75,000 Vietnamese people living in Melbourne, two-thirds of whom are Buddhists. As with temples that Westerner's attend, traditional Buddhist temples operate as a focal point for those with a casual interest in Buddhism as well as more active members. Venerable Sen Kotta Sunthindriya is from the North Buddhist Association in Mickleham, a large temple surrounded by beautiful rose gardens. It has a largely Sri Lankan constituency. The centre has around 250 financial members -not much more than the large Tibetan centres I spoke to. But hundreds would turn up on a special day, such as Buddha's Birthday. Braybrook temple had more than 10,000 people last New Year's day.

In general there is little relationship between different Buddhist groups - neither between western and traditional centres, nor between different ethnic centres. According to Venerable Thich Quang Ba, "Language is an important factor. A lot of ethnic groups are still clinging hard to their own group. They don't have much interest to contact and talk and to communicate and to work together with other ethnic Buddhist groups."

A further reason for this reserve could be that ethnic Buddhist groups tend to be competing with each other for limited cash to fund their centres. Tibetan groups, along with the Taiwanese are better off in this regard as the wealthier people who attend their centres help fund them.

Many Buddhist practitioners have arrived in Australia in the last 25 years, so to some extent the growth of 'ethnic' Buddhism in Australia has been expanding over the same time that Westerners have begun embracing it. However it is only very recently that Western practitioners of Buddhism have begun to engage more fully with traditional Buddhism. Western Buddhists can feel disconnected from the way these communities practise Buddhism, with their emphasis on ritual and ceremony - devotion, if you will - rather than Buddhism's more philosophical components and on meditation.

Gabrielle Laffit, a full time activist for the Tibetan cause and consultant to the Australian Tibet Council talks of the fact that Westerner's engagement with Buddhism often begins as an intellectual thing, even though the religion is at heart ultimately experiential, not intellectual "Emptiness is the fire in which all concept burns." As the years go by Westerners are shifting to a more rigorous and disciplined practice. Lafitt again, "Traditional Buddhism is about devotion and practice and we are just starting that." Traditional and Western Buddhism are becoming closer as Western Buddhism becomes more devotional. Australian Buddhism, it seems, is just beginning that long journey from the head to the heart.Let's consider a fantasy world for a moment, one in which Buddhism; with its emphasis on personal responsibility and compassion was the underpinning philosophy. What would it be like? Many Buddhist practises have much to offer current political debates. Actress Tracey Mann, a practising Buddhist for the last eight years, elaborates. "I opened the paper this morning and there was a photo of another dead body, an Israeli soldier. This is the most important thing for us today: His Holiness the Dalai Lama practices what he preaches. The very least vow you take to be a Buddhist is to not kill."

Sandy McCutcheon spoke to me about Australia's treatment of refugees - several months before the recent Tampa and Woomera Crises. "I hope for the psyche of the nation that there will be a strong Buddhist presence. On a wider lever I hope it will affects the laws we draft, such as those about detention centres."

Professor Falvey believes a Buddhist society "would have deep insight into the interdependence of all things. This is much more than ecology. . Includes inanimate objects, cosmic events . . . Non-violence is a central teaching. Non-violence to self and others. It includes the environment in which one lives.""

"My image of Buddhism is this," McCutcheon told me. 'Years ago, at three in the morning and I heard a car coming down the drive. I thought, 'Oh someone's coming' and went to stoke up the fire. It was wet and misty and cold and I looked out the window and coming across the paddock in a nightie, holding a kerosene light, was a young woman called Chrissie. 'There are people coming,' she said. 'I thought they might be hungry'. That, to me, is the spirit of Buddhism."