Buddhism in the Modern Day Cambodia

Dwindling congregations, a weakened grasp on the young generation and a clergy tainted by scandal. The Catholic Church might be the first association to come to mind. Yet similar challenges confront faiths all around the world, and Buddhism is no exception.

In Cambodia, Buddhism was forced to go underground during the secular tyranny of the Khmer Rouge communist regime. As Buddhist monks and leaders were among the country’s intellectual elite, many were persecuted and killed in the 1970s. Rebuilding the Buddhist community— known as the sangha—has been an ongoing effort ever since.

Moreover, modern ways of life divergent from traditional Buddhist values hardly provide a breeding ground for faith, especially for the young people. Add in a few recent incidences of shameful monk behaviour and it might even be said that the state religion is in crisis.

Or is it?

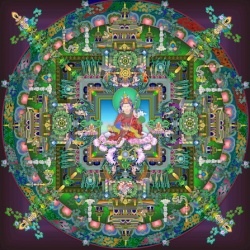

Buddhism became the primary religion of what is now Cambodia in the thirteenth century, although pre-Angkor relics reveal Buddhist iconography dating back to the fifth century. As most visitors to Angkor Wat discover, King Jayavarman VII is credited with turning the formerly Hindu kingdom into a Buddhist realm.

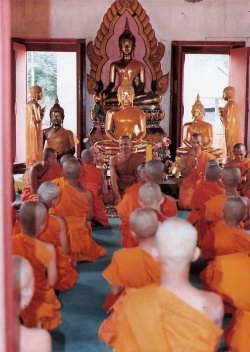

Fast forward numerous centuries. Theravada Buddhism is the official state religion of current-day Cambodia, according to article 43 of the country’s constitution. Approximately 4,000 Buddhist pagodas, known as wats, are found throughout the country and around 95 percent of Cambodians are said to be Buddhists.

Yet how many are practicing? “I go to the pagoda only for Khmer New Year, Pchum Ben holiday and Water Festival,” says a Cambodian bartender in Phnom Penh. “I don’t want to be a monk,” says a tuk-tuk driver. “I want to work.”

A monk and university student, Kim Song, finds that the lack of knowledge about Buddhist beliefs is a problem. “How can the younger generation of Cambodia practice Buddhism if they don’t know about Buddhism? If the older generation did not teach them, how could they know?” he asks.

Absorbing Buddhist principles could be even more difficult for a generation with short attention spans and a myriad of distractions.

“It is hard for young people to go hear monks teach the dharma (Buddhist faith),” says Em Chamnan, another young monk and university student. “They can’t sit for a long time they get a headache they don’t have anything to watch. They fall asleep.”

With the rise of globalisation, Cambodia is no haven from outside influences and the storms of cultural change. Rampant consumerism, high-speed technology and changing perception of morality can encourage a lifestyle that is the antithesis of the traditional Buddhist principles of life. Humility, reflection and charity are simply not the ideals of the modern age.

“They [the younger generation] go different ways from the Buddha’s teachings,” says Pheak, a monk who is studying English. “They think that money is important and that happiness is money, but they don’t think that knowledge and morality is important to them. They like drugs and alcohol, they like girls.”

The Monkhood Meets Modernity

The monkhood is not exempt from the shifts occurring within today's Cambodia. “Monks are basically a reflection of the society around them,” says Peter Gyallay-Pap, a doctor of political science and the founder and executive director of NGO Khmer-Buddhist Educational Assistance Project (KEAP). “Even though they’re supposed to aspire to be ascetic virtuosos, it’s hard. All the lures, the consumerism that’s so rampant, especially in Phnom Penh, I’m sure it has an effect on the monks here.”

Whereas all Buddhists are expected to hew to five precepts in daily life—referred to colloquially as no killing, no stealing, no sexual misconduct, no lying and no indulging in drugs and alcohol—ordained Theravada Buddhist monks must adhere to 227 precepts. Whether through intentional adaptation to the modern age or slack regulation from Buddhist leaders, these precepts are not always obeyed.

Monks using cell phones and riding motorcycles—those scenes of traditionalism intersecting modernism captured by many a tourist’s digital camera—are emblematic of a changing way of life for the Buddhist clergy.

“They have to adapt with the modern day, we cannot see that as bad,” says Say Amnann, a lecturer at a Buddhist university, department director at the Ministry of Cult and Religion and former monk. “Buddhism accepts change. If the Buddha were here, he would allow monks to use cell phones.

”Other Buddhists hold on to more traditional expectations of the monkhood. “I see monks at the shopping mall eating ice cream,” says Sorn Chantha, a sales professional in her late twenties. “It’s weird to me. The monk is supposed to live lightly, not have anything except knowledge. But in Phnom Penh, what I see is exactly different.”

Purity of mind, body and action is seen by some to be the essence of the monkhood—the reason why monks are considered worthy mentors for their believers. When the line between monks and laypeople becomes blurred, respect for Buddhist leadership may be tested.

“In my opinion, what I hear and what I see, monks can have girlfriends. That’s why it’s hard to believe anymore. It’s impossible to trust,” says Sorn. “When I ask a monk for advice, sometimes I am not sure that this person is able to advise me or if what he advises me comes from a clear mind.”

Deviant behaviour by some Buddhist monks contributes to her sense of disillusionment in the monkhood. Sorn cites a much publicised case from last year, when a well-known monk was arrested for producing and distributing pornographic material, made when filming women at a Phnom Penh pagoda in secret.

But Say Amnann warns against letting such incidents blight perceptions of the monkhood as a whole. “If we see that those monks are bad, we start to think all monks are bad,” he says. “But we forget to look at the history, everything is interconnected and interrelated. We have to compare with the good things. I think that the good things are more than the bad things.”

A Pathway to Education

Gyallay-Pap takes a more proactive stance towards the potential corruption of the monkhood. “The number of bad and rotten apples is maybe growing,” he says. “To me that’s all the more reason to be engaged and involved. It means that there’s trouble and help is needed. These people need good education and good teachers."

Strengthening education of monks is a priority of KEAP, which states its mission as to “promote the recovery, renewal and development of the Cambodian people and society through their own spiritual and cultural heritage.” KEAP has run a scholarship programme since 2002 to provide monthly stipends for Buddhist monks so that they can attend universities. It’s part of an effort to reestablish Buddhism as a “wisdom tradition.”

Historically, Buddhist temples were at the centre of academia in Cambodia. But, according to Gyallay-Pap, a national movement to adopt standards from the West and secularise the school system in the 1950s eliminated religious curriculum, and brought education away from Buddhist Sangha control.

Although today Cambodia is abound with state and private schools, education comes at a cost that many of Cambodia’s poorest families cannot afford—the price of books, transportation, uniforms and teacher fees are a barrier for many children.

For young boys, the monkhood offers a pathway to education. Monks are taught elementary courses at the temple, and can receive discounts or free tuition to study at universities.

"My family was very poor after the Pol Pot regime and war in Cambodia,” says Pheak. “If I did not become a Buddhist monk, I could not study at all. I would maybe be a farmer. My father did not want me to follow him, so he sent me to be a Buddhist monk.”

His story is common. At a class at the Preah Sihanouk Raja Buddhist University, nearly all monks present raised their hands when asked if they entered the monkhood younger than age 20. Several students explained that being monks allowed them to pursue an education they would not otherwise have had the opportunity to access.

The Preah Sihanouk Raja Buddhist University is one of two Buddhist universities in Phnom Penh, offering free enrolment to monks and laypeople who pass the entrance examination. The university was founded in 1954 but closed down in 1972 with the onset of civil war. In 1997, the institution reopened and now offers bachelor degree courses in the faculties of Khmer literature, Pali and Sanskrit studies, philosophy and religion, educational and information technology and teacher training—with plans to offer a Master’s of Arts programme in Buddhist Studies. Courses such as accounting and English provide more practical career prospects for those who are not a part of, or do not remain in, the monkhood.

Training the Mind

Lifelong commitment to the monkhood can seem daunting. Often, student monks choose to follow a different life path.

“When they finish education, some want to live as normal people,” says Pheak. “Because Buddhist monks have many rules.”

However, the practice of short ordination can be viewed as a threat to the monkhood’s credibility. “Monks can study for free,” says Sorn Chantha. “They can go to collect money or food in the day so they can survive. They get a degree, and then they become a normal person and get a job. For me it’s not moral to use the monkhood. It’s hard to respect the people like that.”

Heng Sreang expresses similar sentiments. “If they just get ordained temporarily for study, do they still have honest devotion to do the learning or not?” he asks. “We have a lot of temples, we have a lot of Buddhist monks, but the quality is questionable.”

Viewed from a different perspective, the monkhood’s loss could be seen as lay society’s gain. “A lot of our early scholarship recipients, as soon as they graduate, they disrobe,” says Gyallay-Pap. “That’s okay. It’s just a common social rite of passage. You take the vows then you can disrobe whenever you want.”

Up until the 1950s, he explains, it was a common practice for families to send their sons to become monks for a short period of time.

Even if former monks no longer follow the more extensive list of precepts, they may be better steered by Buddhist principles in their actions. They have had an exposure to Buddhist thought and philosophy that many laypeople have not had.

Say Amnann left the monkhood after 22 years. “Being a monk is a nice life,” he says. “However, I felt like I wanted to experience things that I couldn’t [as a monk).” Nonetheless, his background continues to shape his moral judgement. “Decision-making is still connected with Buddhism,” he says.

Although Pheak might not stay in the monkhood for life, he plans to continue being an educator, one of his main functions today, but in a secular capacity.

“It’s really important for us to help people,” he says. “I cannot give money, I cannot give food, but I can give ideas and knowledge. It’s the best way for people to change.”

Buddhist by Nature

Adherence to traditional Buddhist strictures may be increasingly difficult in the modern age, but conversely, some argue it may be more important than ever—and not just in Cambodia.

“In Western countries nowadays, why are people growing more interested in Buddhism?” asks Em Chamnan. “Because they have a lot of money but they are not happy. They want their minds to be peaceful, so they read the teachings of the Buddha they go to Vipassana (meditation).”

Compared with other faiths, Buddhism is more about attaining a peaceful mindset and way of life than religious obligation. Measuring the extent that one is Buddhist has little to do with pagoda attendance. For Cambodians, being Buddhist may simply be engrained in the predominant Khmer culture and patterns of thought.

Gyallup-Pap refers to the recovery and reconstruction process after the Khmer Rouge regime fell. He recounts how people flocked to the wat structures across the country, donating what little they had to strengthen what had been “the social safety net in the country for centuries,” he explains.

That function of Buddhism can still apply today. “(Buddhism is] the social glue in this country,” says Gyallup-Pap. “[Consumerism] is anything but glue, it acts as a solvent on culture and on social cohesion.”

Gyallup-Pap believes that no matter how the young generation may be affected by the modern age, Buddhism is likely to provide an unshakeable foundation for generations of Cambodians to come. “While the leaves and the branches may be decaying and showing signs of wear, I think the roots, deep down, are still pretty healthy,” he says.