Buddhist Texts on Love

Karen C. Lang

Love draws us out into the world, not away from it. But the seeds of love implanted in each of us must be cultivated to become effective in the world. This paper will explore what certain Buddhist texts have to say about the cultivation of love (metta/maitrī/byams-pa). Its intent will be to point out the harmonious message coming from texts of different Buddhist traditions. I. The Buddha’s Discourse on Love (Metta Sutta, SN 1. 8) The Buddha teaches that love is the foundation for all spiritual practice. This love, he says, should radiate out and embrace all living beings. He advocates an unconditional love that knows no boundaries: “May all beings be safe and well, May all beings be happy.”

1. Those who are adept at doing good

And seek to understand the peaceful state should do this: Let them be capable, honest, and straightforward, Easy to speak to, gentle, and not proud. 2. Contented and easy to support,

With few obligations and a simple way of life, With serene sense faculties, intelligent and modest, Let them be unconcerned with society’s material wealth. 3. They should never do the slightest thing That other wise people would criticize.

[Let them make this wish]:

May all beings be safe and well,

May all beings be happy.

4. Whatever sentient beings there are,

Without exception, whether they are weak or strong,

Big, tall, or middle-sized,

Short, thin, or fat,

5. Whether visible or invisible,

Living nearby or far away,

Already born or not yet born--

May all beings be happy.

6. Let no one deceive anyone else

Or despise anyone anywhere at all.

Let none through anger or animosity

Wish each other harm.

7. Just as a mother would protect

With her own life her child, her only child,

In the same way, for all sentient beings,

Cultivate a heart that knows no boundaries

8. And with love for all the world

Reaching above, below, and all around, without any barriers, Freed from hatred and hostility,

Cultivate a heart that knows no boundaries.

9. Whether standing or walking, seated, or lying down, As long as wakefulness persists,

Develop this mindfulness.

This is the sublime state here and now.

10. And after letting go of wrong views,

The virtuous, endowed with clear vision,

Conquer desire for sensual pleasures,

And never again enter any womb.

The Metta Sutta indicates that love must be cultivated. Abundant love for all sentient beings grows with patient cultivation and takes root in a heart that cherishes all with the same self-sacrificing love that a mother feels for her child. The warm and compassionate heart that develops through the practice of cultivating love extends first to our circle of friends and finally reaches outwards to those who would do us harm.

II. The Jātaka tale of the virtuous dog and the unjust king The stories of the Buddha’s past lives (jātaka) -- both as humans and as animals-- illustrate Buddhist virtues. Many of these stories are part of the common heritage of Indian folklore. Their Buddhist affiliation comes from the Jātaka’s commentary, which clarifies the moral message of the tale and identifies the hero as the Buddha in a past life. The Jātaka stories in which animals are the main characters tell us little about animal behavior. Stories that seem to be about animals are in fact stories about situations that face human beings. Charles Hallisey suggests that using animals as "ethical exemplars" provides a skillful way of discussing moral virtues without specific references to class and gender.563 Paramount among these virtues are love and compassion.

In the Pāli Kukkura Jātaka, (Ja I 175-78, Fausbøll no. 22) the bodhisattva’s past actions resulted in his rebirth as the head of a large pack of dogs living in the cremation grounds outside the city’s gates. One night, after the king had returned from a day pleasurably spent in the royal gardens, his chariot was left out in the rain. The king’s own hunting dogs sunk their teeth into its soft leather reins. The next morning, his servants told him: “Your majesty, stray dogs came in through the sewer’s drains and have gnawed the leather reins of your chariot.” The angry king ordered the death of all stray dogs. Some dogs escaped the slaughter and fled to the cremation grounds where they told the bodhisattva of the death sentence that all the dogs faced. The bodhisattva knew these dogs were innocent since the palace was impenetrable. It had to have been an inside job. Motivated by his cultivation of love (mettābhāvana) and his resolution to save the dogs’ lives, he made his way into the city, saying as he went, “Let no hand be raised to throw a stone at me.” He entered the king’s chamber and challenged his order: “Your majesty this is unjust.

You don’t know for certain which dogs chewed the leather yet you have ordered that all dogs be killed on sight.” When further questioning reveals that the king’s own dogs were spared, he accused the king of favoritism and of slaughtering only the weak and unprotected dogs. He then proved king’s dogs guilty by feeding them buttermilk and grass that made them vomit the leather they had chewed. The king then honored the bodhisattva who taught him the five precepts. From that time on the king ruled justly and protected the lives of all creatures within his kingdom. The Madhyamaka scholar, Candrakīrti (c.570-650 C.E.), in his commentary on the fifth chapter of Āryadeva’s Four Hundred Verses (Catuśataka, bZhi rgya pa, D ff.100b-101b), cites an abbreviated version of this jātaka,story, which begins: “The bodhisattva knew that in the future harm would come to dogs, so he took birth as a dog.” Candrakīrti comments that great compassion inspires bodhisattvas to choose an inferior birth rather than remain in meditation enjoying “the inconceivably sweet tasting food of the Tathāgata’s teaching.”

Their exceptional love (vatsala) for sentient beings motivates them to set aside their own vast merit and voluntarily return to the world as lowly animals. In both versions, the dog enters the king’s assembly hall and convinces the king to spare the dogs’ lives and become a just ruler. But Candrakīrti’s dialog has a distinctly adversarial tone. “You have devoured the leather on my horse chariot. You’ve come,” the king said, “but you’ll not be released.” “If am unsuccessful [in convincing you],” the dog responded, “I certainly deserve to be punished.”

“Since you ate the leather, how,” the king asked, “can you be successful?” “You and the palace attendants should listen to me. Animals don’t know what should and shouldn’t be eaten,“ the bodhisattva explained. “First of all, even if I did eat the leather, the guards were inattentive, so I’m not to blame. How can all the dogs in the country, cities and villages be at fault? If one dog alone ate the leather, then all the others did not. The king’s order-- ‘Kill all of them’-- is unjust.“ In this version, no dogs—not even the king’s guilty hounds--are blamed since they all lack the intellectual capacity to judge what is fit to eat. The blame instead falls on the human guards who were not paying proper attention. The story concludes: “This wondrous human speech captivated his heart and appeased the king’s anger. He reversed his order to harm the dogs and became devoted to righteous conduct.” The wonder of a talking dog seems as influential in convincing the king as the bodhisattva’s rational arguments. The canine bodhisattva’s skilful use of his wonder-working powers enabled him to convert the king to nonviolence and rescue both the king and his intended victims from the harmful consequences of his anger. Love is shown here as the remedy for anger. The virtues of love and compassion exemplified by the bodhisattva extend not only to his canine companions but also to the irate king who had intended to kill them all. A jātaka story of a mother’s love

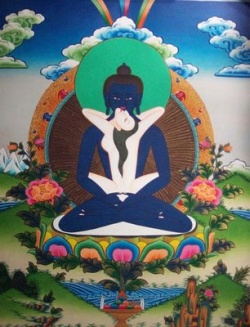

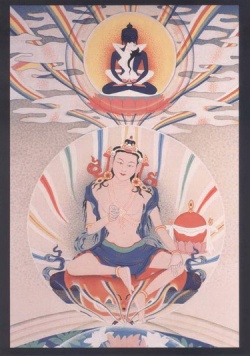

The great compassion (mahākaruā) that characterizes Mahāyāna bodhisattvas has its beginnings in the more modest cultivation of love (maitrī). Mahāyāna scriptures compare the Bodhisattvas’ love for all sentient beings with the love that a mother has for her only child. Unlike a mother’s love, sometimes criticized as being tarnished by her attachment,564 bodhisattvas love all beings with irreproachable impartiality. The jātaka stories and examples Candrakīrti cites, however, emphasize the positive effects of a mother’s love. In the Pāli Kahahāri Jātaka (Fausbøll Ja I 133-35 no. 7) the bodhisattva is a young boy taunted by other children because he has no father. The story begins with the circumstances surrounding his conception. One day the king saw a young girl gathering flowers in the meadow.

His passion aroused by her beauty, he seduced her and she conceived a child. He gave her a ring from his finger and told her: “If the child is a girl, use the money from selling this ring to bring her up but if it is a boy, bring the ring and child to me." After the bodhisattva’s mother answered her son’s question about his father’s identity, he insisted that she take him to the king. But the king refused to acknowledge the child was his until an act of truth (saccakiriyam) convinced him. The mother hurled her child in the air and said, “If you are the father of my child, may he remain in mid-air; but if not, let him fall to the ground and die.” The child remained seated cross-legged in the air until his royal father’s arms reached out and embraced him. He was made the king’s heir and his mother, a queen. In Candrakīrti’s telling of this story, there is no promise that a ring will bring recognition. The bodhisattva’s mother knew the king would deny his responsibility and would have her punished for even suggesting it. Nevertheless, motivated by her love for her son and his insistent tears, she acted to ease his suffering (D ff.101a-b): 564 See Ohuma (2007).

Then, because her son’s pain struck at her heart, she approached the king, who was seated and surrounded by his attendants. She pointed out the boy with a gesture of her hand. But the king remained with his face turned away. Urged by the boy, she went over in his direction and points to her son. Again the king remained just as before. The boy pleaded with his mother: “What’s the use of hand gestures? Speak up!” Because of her son’s anguish, she said to the king in words that spread through [the chamber]: “Your Majesty, please acknowledge your son. I’ve cared for him until now.”

The embarrassed king ordered his men: “Beat this woman who is telling lies!” Bearing whips in hand, they advanced. The bodhisattva, like the goose king spreading his wings, flew up from his mother’s lap and seated in sky, asked the king: “Aren’t you pleased that I’m your son?” The king, the hair on his body standing on end, shed a few tears, rose from his golden throne, extended both his arms and in a voice choked with emotion, said: “Precious child, please come down.” This story differs significantly from its Pāli parallel. The bodhisattva directs the action. He orders his mother to speak up when her gestures are ignored. He leaps out of her lap and challenges his father. The bodhisattva’s skilful use of supernatural power (ddhi) leads to the emotional embrace at the story’s end.

His mother plays a supporting but important role; her love enables her son to claim his royal lineage. Candrakīrti concedes that a mother’s love is not impartial but, instead of criticizing maternal love as selfish, he recognizes the benefits of directing love and compassion toward those most in need. The minds of compassionate bodhisattvas are impartial toward all sentient beings but their compassion is directed particularly toward people who suffer now because of their afflictions (kleśa) and who will suffer in the future because of painful rebirths. Like the advice expressed in the Buddha’s Metta Sutta, the Mahāyāna bodhisattva cultivates a heart that knows no boundaries. But in contrast to the final words of the Metta Sutta “never again enter any womb,” the Mahāyāna bodhisattva vows to enter wombs again and again. As Candrakīrti explains (D f. 100b) that since bodhisattvas have powerful minds incapable of regressing, no afflictions trouble them as they move through the cycle of death and rebirth. “Because the suffering of birth, death, old age, and so on, doesn’t exist for them, there’s no difference for bodhisattvas between the cycle of death and rebirth and nirvana.“

III. Śāntideva on the bodhisattva’s cultivation of love and compassion Śāntideva’s works, written circa eighth century CE, the Śikāsamuccaya (Collection of Instructions), and the Bodhicaryāvatāra (Introduction to Bodhisattva’s Practice) emphasize the importance of cultivating love and compassion. In the Śikāsamuccaya, he explains that bodhisattvas direct their love towards sentient beings by first directing their minds towards happiness and wellbeing of those dear to them, then to friends and strangers, continuing to expand their love to people who live close by and far away, and finally to everyone in all ten directions. Love is wanting others to be happy while compassion is wanting others to be free of suffering. Śāntideva, in the first verse of the Śikāsamuccaya, says: “When neither I nor anyone else wants fear or suffering, then what’s so special about me that I protect myself and not others?” He repeats his belief that we have no reason for privileging our own happiness or our suffering over that of others in the eighth chapter of the Bodhicaryāvatāra. There’s nothing special about my happiness or my suffering, so why he asks, (BCA VIII.95- 96) do we focus so intently on our own? Since I and others are the same in wanting to be happy, what is so special about me that I seek happiness only for myself?

Since I and others are the same in wanting to avoid pain, what is so special about me that I protect myself and not anyone else? He concludes (BCA VIII. 129) that: All who suffer in this world do so because of their desire For their own happiness.

All who are happy in this world are so because of their desire For the happiness of others.

Śāntideva emphasizes here that both our suffering and our happiness are deeply connected with the way we engage others.

Śāntideva’s compassion, Jay Garfield observes, is founded upon the insight that suffering is bad, regardless of whose it is:

This is a deep insight, and one over which we should not pass too quickly: the bodhisattva path is motivated in part by the realization that not to experience the suffering of others as one’s own and not to take the welfare of others as one’s own is to suffer even more deeply from a profound existential alienation born of a failure to appreciate one’s own situation as a member of an interdependent community.565 The bodhisattva’s compassion and active engagement in ending others’ suffering is rooted in the profound insight that all beings in this world are intimately bound together. Śāntideva in the final verses of the Śikāsamuccaya stresses the importance of cultivating love, developing the aspiration for enlightenment (bodhicitta), and giving others the spiritual gift of the Buddha’s teachings.

In the last chapter of the Bodhicaryāvatāra, (BCA X.55-56) he emphasizes the power of the bodhisattva’s compassionate vow: As long as space endures, as long as the world endures, May I remain, dispelling the sufferings of the world. Whatever suffering the world has, may it all ripen on me. May the world find happiness through the bodhisattvas’ virtues. Conclusion All these texts share a similar message. The warm and compassionate heart that develops through the practice of cultivating love must extend beyond our friends and family to encompass people living even in remote regions of the globe. According to the Metta Sutta the Buddha instructed his followers to radiate love and compassion out to all beings in all directions. The jātaka stories illustrate how the bodhisattva’s cultivation of love culminates in great compassion for sentient 565 Garfield beings.

The great compassion that bodhisattvas have empowers them to return voluntarily to this world in a variety of rebirths, including despised dogs and bastard children. In their works, Candrakīrti and Śāntideva repeatedly stress the importance of cultivating love, compassion, and the lasting power of the bodhisattva’s vow. Even better than giving a jeweled stūpa for a Buddha’s remains, Candrakīrti argues, is giving the gift of the teaching and educating others to develop the aspiration for enlightenment. He tells the story of a dead man’s two friends to reinforce his argument. One friend washes the corpse and prepares the body for cremation. The other friend takes care of the dead man’s widow and their children. The second man’s actions are better. Similarly, he says, better than honoring the relics of dead Buddhas is the work of living teachers who sustain the Buddha’s lineage by encouraging others to become bodhisattvas and thus enabling the Buddha’s teaching to last for a long time.

Abbreviations and References

BCA = Bodhicaryāvatāra

Ja = Jātakāhakathā.

SN = Suttanipāta.

D = Derge edition of the bsTan’ gyur

References

Bodhicaryāvatāra. (1960). Edited by Vidhusekhara Bhattacarya. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society.

Byang chub sems dpa'i rnal ‘byor spyod pa bzhi brgya pa'i rgya cher ‘grel pa. Derge edition of bsTan’ gyur vol. Ya ff. 100b-101b.

Clayton, B.R. (2006). Moral Theory in Śāntideva’s Śikāsamuccaya: Cultivating the fruits of virtue. London and New York: Routledge.

Garfield, J.L. (2010-2011). What is it like to be a bodhisattva? Moral phenomenology in Śāntideva’s Bodhicaryāvatāra. In Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 33 (2010-2011): 333-358. Hallisey, C. and Anne Hansen. (1996). Narrative, Sub-Ethics, and the Moral Life: Some Evidence from Theravāda Buddhism. In Journal of Religious Ethics 24 (1996): 305– 25.1948. Jātakāhakathā. Edited by V. Fausbøll. vol.1. London: Pali Text Society. 1877-96. Reprint, London: Pali Text Society, 1962-64.

Ohnuma, Reiko, (2007). Mother-Love and Mother Grief: Pan Asian Buddhist Variations on a Theme. In Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 23.1: 95-106. Śikāsamuccaya. (1957). Edited by Cecil Bendall. 's-Gravenhage: Mouton. Suttanipāta. Edited by D. Anderson and H. Smith. London: Pali Text Society, Suzuki, K. (1994). Sanskrit Fragments and Tibetan Translation of Candrakīrti's Bodhisattvayogācāracatuśatakaīkā. Tokyo: The Sanibo Press.