Photo essay by Emily Yeh.

Mount Kailash, or Gang Rinpoche (Gangs rin po che), is associated with Mt. Meru, the axis mundi or center of the world, and is thus considered one of the world’s most sacred mountains. Four major rivers – the Indus, Sutlej, Brahmaputra, and Karnali – originate in the four cardinal directions nearby. As such, it is a destination for pilgrimage and circumambulation for Tibetan Buddhists, Bonpos, Hindus, and Jains. Tibetan Buddhists consider it a dwelling place of Demchog (Chakrasamvara) and for Hindus it is the abode of Lord Shiva. For Jains, it is the place where the first Tirthankara attained enlightenment, and for Bonpos, Mt Kailash is a nine-story swastika mountain that is the seat of spiritual power. Moreover, the region of the mountain and nearby Lake Manasarovar is where Thonpa Sherab founded and disseminated Bon.

Located in western Tibet, near the contemporary borders of the PRC, Nepal, and India, the symmetrical cone-shaped Mount Kailash, at 6638 meters (21,778 feet), rises alone above the rugged landscape. Tibetan pilgrims typically complete the 52-kilometer circumambulation route over the 5600-meter (18,500 feet) Dolma La pass in 15 hours, rising at 3am and finishing at 6pm. Most do more than one circuit; we met quite a few groups of pilgrims who had done or were planning to complete 13 circumambulations. One Bonpo pilgrim in his 50s, a former businessman who had renounced everything, had walked the circuit 800 times over five years and was planning to complete 1000 circumambulations altogether. Still others complete the circuit doing full-body prostrations. Whereas Buddhists and Hindus circumambulate clockwise, Bonpo pilgrims circumambulate counter-clockwise.

At the time of our visit, most Tibetan Buddhist pilgrims we met were from Ngari prefecture, especially from Gerze, Gegye, and Tsochen counties. We also met pilgrims from Nyingtri, Dechen (Yunnan) and Kyirong. The Tibetan Bonpos we met were mainly from Bachen County in Nagchu and Dengchen County in Chamdo. Passing each other as they walked in opposite directions, they greeted each other with “blessings” (byin rlabs byed) or “Tsering!” (“long life,” a common greeting in Nagchu).

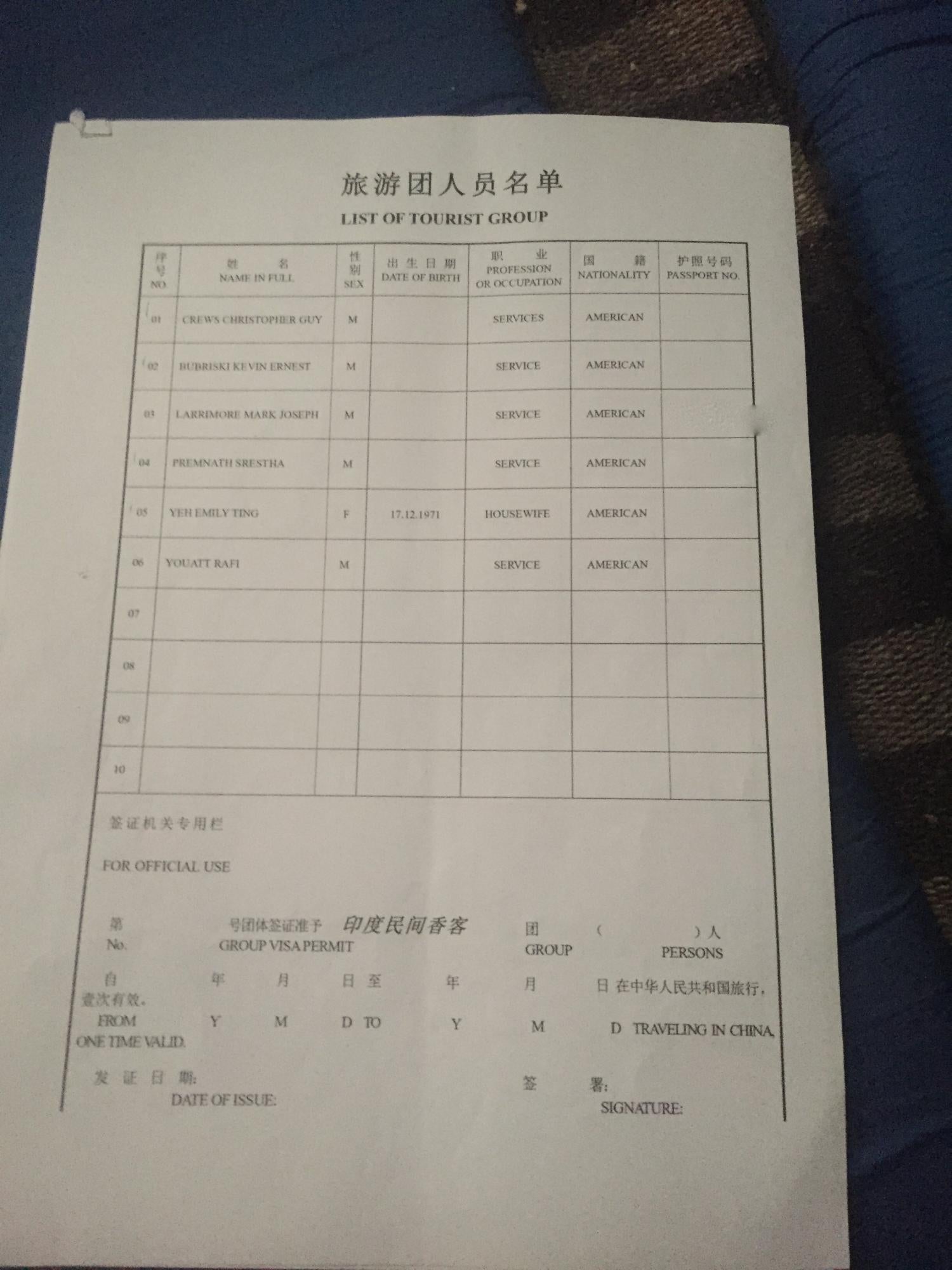

There is now a government agreement in place that allows Indian pilgrims to visit Kailash and Manasarovar. However, the quota to come directly from India, which requires a long trek, is very limited and so most Indian pilgrims instead fly through Kathmandu and visit through private tour operators. Upon arrival in Simikot, they take a 15-minute helicopter ride to the border (in contrast to our many-day walk) and then head directly for a ritual bath in the waters of Manasarovar. Because of their sudden arrival at very high altitudes, twelve pilgrims had already died in 2016 when we visited.

Along the route, Tibetan pilgrims visit monasteries and other important sites. Among these are a number of footprints, including those of Milarepa, the Buddha, and Gyalwa Gotsangba (who ‘opened’ the circumambulation path in the thirteenth century), as well as numerous self-arisen forms, including a saddle of King Gesar, the Karmapa’s black hat, and prayer beads. Pilgrims touch the various manifestations with their own prayer beads or bow to touch their foreheads upon them. In still other places pilgrims test their level of merit, sin, and fortune through physical encounters with the landscape.

Lake Manasarovar (ma pham g.yu mtsho, the Unconquerable Turquoise Lake) lies at 4590 meters and is located to the south of Mount Kailash. Pilgrims also circumambulate the lake, which is eighty-eight kilometers in circumference. This is now possible by car as well as foot. For Hindus, bathing and drinking from the lake cleanses all sins and guarantees going to the abode of Shiva after death. Though Kailash is now the more important focus for Tibetans, there is considerable historical evidence that the earliest sacrality was of the lake rather than the mountain. Indeed, Alex McKay has found that as late as the early 1900s, Kailash was more an ideal heavenly place than one associated with any particular place on the earth’s surface. He finds little evidence that the earthly mountain was considered sacred until the twelfth or thirteenth centuries, or that Kailash was considered the premier pilgrimage site of Tibet until the twentieth century. Its emergence as sacred in the 12th/13th centuries was related to a power struggle between Buddhism and Bön, now told as a contest between the magical powers of Milarepa and Naro Bönchung.

Our visit to Kailash, Manasarovar, and the associated sacred site of Tirthapuri was motivated by a proposal by ICIMOD to have Nepal, India, and China nominate the larger Kailash Sacred Landscape as a transboundary World Heritage Site. Our goal was to understand historical pilgrimage routes, document the cultural landscape, assess current tourism, and seek to understand what effects such a designation, were it to come to pass, might be.