Compassion & The Nine Yanas

Oneself as the Basis

There is a book by Kyabjé Kalu Rinpoche with the most appropriate title I have ever seen. It is called ‘The Dharma ’. Now, ‘Dharma ’ is a word I rarely use. I rarely use this word because I have too much respect for it to make an adjunct of it. I usually use the word Buddhism when I talk about the religion to which I belong. But Dharma is not actually a thing – it means ‘as-it-is’. Dharma means ‘reality ’ – so I use the word with caution. ‘Dharma ’ could actually be the title of every Buddhist talk, and the title of every Buddhist book. In a sense we have no need to sell Dharma with descriptive titles, and the reason we do so is in order to express and communicate the particular manifestation of Dharma we represent as Dharma teachers.

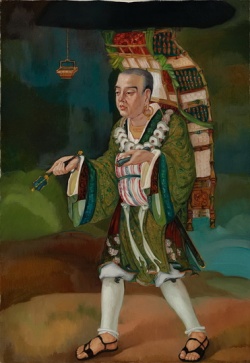

I belong to the Nyingma School. It is the oldest school of Buddhism in Tibet . It is not really a ‘school’ in the sense in which Sakya , Kagyüd, and Gélug are schools – it is a school by virtue of the fact that these other schools arose at a later date. Nyingma is simply the Buddhism which arrived in Tibet with Padmasambhava , and which was continued by Yeshé Tsogyel and the disciples of Padmasambhava . There are 25 disciples who are well known, Yeshé Tsogyel and twenty four male siddhas – but there are also 21 female siddhas . The female siddhas are less well know, but their accomplishments rival those of the male siddhas and in several cases surpass them in their outrageous quality. Nyingma , or Nga’gyür Nyingma , means ‘Old Translation School’. It is called ‘Old Translation School’ because there arose the three ‘New Translation Schools’. The idea of ‘school’ is more like family style. There is no great difference between the schools; but they all have their own style of presenting and organising Dharma . What is important is how one can actually apply Dharma within one’s life .

Within the Nyingma School, there are two strands of practice. One is monastic and the other non-celibate. The non-celibate sangha is call the gö-kar-chang-lo’i-dé. Khandro Déchen and I are members of the gö-kar-chang-lo’i-dé. There are many ways of describing these sanghas. Often they are spoken of as the two divisions of the sangha of ordained practitioners (dGe bDun gyi sDe nyis). In this way of explaining there are ‘the renunciates with shaved heads’ or ‘the division of Vinaya ’ (‘dul ba’i sDe), and ‘those with uncut hair and white skirts’ (gos dKar lCang lo’i sDe) or ‘the division of Mantra ’ (sNgags kyi sDe). Both are distinguished from the sangha of ordinary individuals the soso’i kyé-wo gendün (so so’i sKye bo’i dGe ‘dun).

There are few things in life that irritate me; but the word ‘lay’ is one. I would like to define what is meant by ‘lay’. When I became aware of this word’s usage with regard to the white sangha , I looked it up in American and English dictionaries; then I asked French and German people what this word meant in their dictionaries. It was interesting that it was all the same definition: The word ‘lay’ meant not of the clergy, non-professional, an amateur. To have someone like Düd’jom Rinpoche or Dilgo Khyentsé Rinpoche described as a ‘lay’ master is bizarre. In the Nyingma School, and also in the Kagyüd and Sakya Schools, you had people who were both monastic – that is, they were celibate ordained people, you had white sangha members who were ordained but non-celibate, and then you had people who were non-ordained but who were high level practitioners, whom you could not categorise as non-professional or amateur in any way.

There are many different ways of practising. I am ordained into the white, or ngak’phang sangha . In Tibetan , ngak means mantra . Phang means hurling or throwing. In Sanskrit it is mantrin / mantrini. This is a non-celibate ordination. Another word for this lineage of ordination is gö-kar-chang-lo’i-dé. Gö-kar is white skirt; chang-lo is long-hair . This is a different ordination in outer appearance to the monastic ordination, because we do not have shaven heads. We wear the same shape of robes , but it is in different colours.

From the point of view of Sutra the hair is shaven off. In Hindu culture hair is a mark of defilement; it is something put out by the body. As a symbol of cutting off defilement, the hair is shaven off. In Tantra , because Tantra is the path of transformation, the hair is left uncut; the defilements are worn as an ornament. This is an important principle of Tantra . The idea is that however we are, whatever style of neurosis we have is intimately connected with our enlightened state – because it is our enlightened state. If I am an angry person, a sad person, a greedy person—whatever style of neurosis I have—is simply a distortion of the realised state. It is not something other than the realised state. It does not fall into the category of evil —that which is opposed to that which is good—that is totally different, disconnected. However we are, we are connected with the realised state. Whatever the degree of distortion, the energy there in its pure form is always the realised state. As a symbol of this in the ngak’phang sangha we leave the hair uncut.

The tube that is worn in the hair is called a takdröl. Takdröl means ‘liberation on wearing’. It is a representation of the presence of one’s teacher ; and it is given when someone begins to teach in this tradition . It is part of the symbol of wearing the defilements as an ornament – so the hair is wrapped round it, and it is tied up on top of the head. The ngak’phang sangha , then, owes its origin to the Tantras and holds to the Tantric vows . It does not hold to the Sutric vows , in terms of how one regulates one’s life , as does the monastic ordination.

I remember being at a Buddhist conference, and there they were talking about the white sangha , or yogis and yoginis, as being half way between lay and monastic ; as if that were the polarity. This had never been the case. This is a modern contrivance in Western languages. Ordination in terms of white sangha means that one is a Tantric practitioner. It is a different style of ordination, which is not half-way between anything and anything. The whole half-way-between idea is completely artificial.

It is important that in the West, if we are to practise, we need to have an idea of ourselves as people who are taking something seriously. If the only way we can take something seriously is to be a monk or a nun , then we have to adjust to the idea that we are not taking it seriously. Now, if you are not taking this seriously, why are you engaging with these teachings? Or why are you not thinking of becoming a monk or a nun ? If you do not have this idea, then you have to look at what all that means. For me it is important that people have an idea that they are practitioners; not second-rate or second-class practitioners because they are not celibate. They are practitioners and that is the way they are practising. That is crucial. This is also connected with the word bodhicitta , or active-compassion . The principle here is that one’s practice is integrated with one’s life .

Buddhism as Method in Relation to the Yanas :

We come from a culture that looks at religion as truth ; there has got to be right and wrong with truth . For some people, that causes a lot of problems with Buddhism – Buddhism is 99% method. When we look at Buddhism from a Judæo-Christian perspective, we have a problem: There cannot be different truths; otherwise you have to redefine what is meant by truth . That is a definition of yana – how we redefine truth . If there are different truths, then we have to say: "What does that mean? Who are they true for?" As soon as you get to that point, then you are discussing yana .

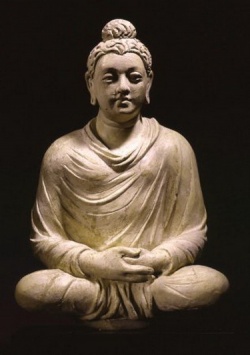

That is important: Buddhism is method; it is a way of realising truth . The expression is not necessarily truth in itself – it is not ‘the word’ as written that is truth . Everything within Dharma is a sign-post to that, something that helps you find that. But ‘the Dharma ’ can never be expressed. If you look in the Sutras , you will find that Shakyamuni Buddha said: "I never taught the Dharma . The Dharma is non-existent." Apart from looking at that as some highly profound statement that one cannot understand, one can look at this as an expression of method. However Dharma is expressed, it is simply a method from which one can realise Dharma .

It is only in recent times that we have had dictionaries. Words shift in meaning all the time . When I was young, there was this idea of ‘slang’. There was real language —the language of the dictionary—and then there was slang or local usage, which was not really respected. Now you can find words such as ‘hassle’ in the dictionary. It always occurred to me that if someone understood the meaning of the word, then it was a word and you could use it. It had a meaning.

If you look at the dictionary and see what words mean, and then you see how people use them, they are different. The word ‘share’ for example. This is an interesting word. When someone said: "I would like to share something with you," I always took this to mean that they had something valuable and were going to give me a bit of it – their sandwich, their pork pie, their bottle of beer, whatever. But, no! I was wrong. The real meaning of the word ‘share’ seems to be: "I have got some stupid idea that I want to bend your ear with for half an hour." The real meaning seems to be ‘take’ – I want to take your time with my idea. I hear: "Let me share something with you," and I think: "No! You are too generous! You keep it! Far be it from me to take your great idea." That is interesting – how words shift.

Because words change in meaning, Dharma always has to be re-expressed. There cannot be a fixed Dharma in terms of what is expressed. That is why there is always a problem in courts of law, if a Buddhist has to swear on something. The extent of what you would have to swear on would take up the entire courtroom – because there is so much Dharma , and it gets bigger all the time . There is no book that you can say: "This is it – it is all contained here." Or you simply could have the letter A—you could swear on the letter A—it could be the same thing.

Dharma expands all the time ; because wherever there is misunderstanding, there is more Dharma . That is the whole idea – that Dharma continues to be re-expressed all the time , in the language that people understand, in terms of how they can integrate that into their experience. Expression—how a teaching is given—is based on understanding. How a person understands, what their vocabulary is—what these words mean in terms of their connotations and implications, their colour and texture—is all part of how one works with a person. This is also connected with yana .

Accepting Oneself as the Basis:

Question: You mentioned neuroses and negative behaviour. Do you feel it is better to allow oneself to exhibit negative behaviour? That it makes it easier to look for enlightenment …? How do you feel about behaviour modification – modifying negative or unpleasant behaviour?

Ngak’chang Rinpoche : Here we are not talking about behaviour; we are talking about what is arising internally. It is obviously useful that one modifies one’s behaviour – that is really not in question. The principle of Tantra is not to advocate that one ‘acts out’; but that one accepts oneself – as the basis. However you are is the perfect basis from where you travel. You have to start from where you are; you cannot start from anywhere else. It is important that one respects the base; and the base is what I am. If I have anger , then that is part of my base – I have to work with that. I cannot go into denial about being an angry person – I cannot pretend that I am not angry, that I am not always irritated. I have to accept that about myself. I cannot try to be a ‘spiritual ’ person, and enter into pretence about myself. I have to be simply what I am, and work with that. It is not that I validate my own behaviour in some way. It is important that one regulates one’s behaviour. If you do not regulate your behaviour, then you are completely out of control; and that is not useful. That is a whole different area – to accept what I am; to say: "Right, now I have to look at why I am what I am. Where is this coming from?"

That is the issue of embracing emotions as the path , which is central to Tantra . It is more the Sutric way to modify what I am feeling : if anger is arising, then I will cultivate compassion , in order to modify this feeling of anger . But in terms of Tantra , the approach is different. The approach there is to acknowledge this energy within myself, and to enter into some form of practice – not to negate that anger , but to experience it in its nondual state. Anger , for example, in its nondual state is described as clarity. Embracing emotions as the path is a whole discussion in itself.

The Confusion of Psychology and Buddhism :

The other part of what you were asking deals with an area that I think is quite crucial – that is the confusion of psychology and Buddhism . They share various interests, but they are not the same; nor are they part of the same paradigm. One has to have a clear idea of which is which – what their aims are, what they deal with. Part of understanding yana is to have a healthy respect for psychotherapy, to understand what task it performs for human beings and to value it within its own sphere; and then to value Dharma within its own sphere. If one confuses them, it becomes problematic.

Psychology , from certain points of view, is about integrating oneself into the social norm. I know that does not comprise the totality of psychology and psychotherapy; but that would be a generalisation that one could make. Dharma is not necessarily about doing that – Dharma is not necessarily about becoming a happier person. It is about understanding the nature of reality ; it may not always be about finding oneself in a better integrated position.

Q: Is there a relationship between Jungian psychology and the process of individuation, and the process of realisation?

R: I am a-Freud I am too Jung to know about that. I have been waiting for years to say that [laughs]. I cannot say too much about individuation. Freud’s concept of oceanic experience, with regard to the infant, is interesting . Psychology is a language , a set of terminology, that Buddhism can find useful; I find various modes of expression through that. Trungpa Rinpoche was the first Lama who started using the word ‘neurosis’ as a term. Obviously there is a relationship between the two; but one has to be careful of it, and not take one for the other.

Bodhicitta

Bodhicitta , Chang-chub sem:

The word bodhicitta , or chang-chub sem, is much larger than the word compassion . Compassion , in a way, means ‘feeling for others’. What is meant by bodhicitta or chang-chub sem is vast, and it is distinct in each yana . We will look at how that applies to us, in terms of the energy we experience in being alive – what that is as a communication. Almost every technical term you find within Buddhism is huge – it is a symbol that spreads out in its meaning. Almost whatever I talk about, it is emptiness and form – the heart of Buddhism is the exploration of emptiness and form . This is the expression of the Heart Sutra – form is emptiness , emptiness is form . What is the quality of form , what is the quality of emptiness ? How do we split the dictionary in half and call one half form , one half emptiness ? That is our language – comprehension, incomprehension; security and insecurity – all these pairs of emptiness and form words. Compassion is a form word; form is compassion . One of the things we will look at is how form manifests as compassion in many different ways. The chief characteristic of form is impermanence . Form is impermanence , change – that is why we talk of Dharma as being form . Dharma is form , Dharma is compassion ; compassion is impermanent , that is, changeable, modified. It is never the same thing, because circumstances are infinite. This is why compassion is form – it is not fixed. Within the yanas , compassion —bodhicitta , chang-chub sem—manifests in many different ways according to practice, according to orientation.

Q: I didn’t understand the difference between compassion and bodhicitta , that bodhicitta is vaster? What is the difference between compassion as feeling for others, and bodhicitta

R: Compassion is an English word – I would not use compassion as a direct translation. One would have to say ‘active-compassion ’. Compassion in terms of a feeling , if it is amorphous enough, is more akin to wisdom than what is meant by bodhicitta . Compassion is a word that is used when we link it with practice at the level of Sutra – kindness towards others, putting others first. This is a kind of practice that is understood everywhere, in many different religions . Bodhicitta is a technical term. Bodhicitta is always energetic, changing, moving. In Buddhism there is a careful analysis of how that is, how that manifests, in terms of being a practice of nonduality . Here we have compassion as the exploration of self and other, in terms of duality and nonduality . When I split self and other, or when self and other are indistinguishable, that is the approach through Sutra . Then the approach through Tantra is different. In each yana it is different. We can start in terms of our everyday experience, because we have self -orientation. The most immediate start for people is orientation towards other. To say: ‘There are my concerns; but there are also your concerns.’ It is more comfortable if I ignore your concerns; but then I have to cut myself off from you – I have to be separate. We have questions of separateness and connection. This is a Sutric issue. In terms of Tantra , bodhicitta has more the meaning of energy. This includes lust , desire , passion , appreciation – because all these words are about connection. Tantra is interesting at this level, because it starts looking at all the ‘ugly’ words, in terms of a Sutric approach: ‘I must not do, I must not desire things, I must not lust after, I must not be greedy.’ But in Tantra one finds terminology like ‘vajra pride’, ‘vajra stupidity’ – it has a penchant for using these words and inverting them. One adds the word vajra , which means indestructible, which links this word with the empty state; and suddenly, we are talking about something different. Here the emphasis is on energy; we move into a different dimension in terms of connection. One can see that whenever one speaks of bodhicitta or compassion , connection is what is important.

It should be sufficient to say, ‘Form is emptiness , and emptiness is form – they are nondual. Work it out for yourself! [laughter] That is actually all there is; one needs no other instruction, if one can really follow that, because it explains itself. If one has some experience of emptiness and form within oneself, then that starts to have some life . What is emptiness and form ? What is that in me – in terms of comprehension and incomprehension, anxiety and safety? What is it in terms of hope/fear, praise/blame, meeting/parting, gain/loss? These polarities are the jig-ten chö-gyèd, the eight worldly Dharmas , and are expressions of emptiness and form . Everything within Dharma is an expression of emptiness and form and how they are nondual. Real compassion , from the perspective of Dzogchen , is nonduality . One cannot have compassion without wisdom – compassion can only be compassion where there is wisdom , where they are nondual. Buddhism is comprised of methods that unify wisdom and compassion .

Q: Does that mean to say that in order to have true compassion , there has to be a certain level of realisation? Or anybody can have compassion , regardless of what state they are in?

R: What do you mean by compassion there?

Q: Well, you said that compassion comes from the state of emptiness . In other words, to really experience compassion , you need to be in that state of emptiness ?

R: And then you said, can anyone have it, or is it exclusive?

Q: Is there a true experience of compassion ? Or are there grades of compassion ?

R: It is a sliding scale, according to where you are and what your experience of emptiness is. We could look at it as a socio-political construct: When there is sufficient affluence within a society, people become more compassionate . When the level of affluence dips, then people become less compassionate – they start looking after themselves. That higher level of affluence means space: I am not in a state of claustrophobia about my situation. I am not having to fight other people off, so I am somehow more relaxed about my existence. Therefore I am more concerned about the existence of others. It manifests in every kind of condition.

That is the thing I personally like about Buddhism – it is everything, because everything partakes of its analysis. You can look at society, you can look at everything through it – in terms of the interplay of emptiness and form . What is required for compassion to exist is wisdom – and wisdom is emptiness . Emptiness is the space in which compassion can arise. In order to have compassion , then, silent sitting is important. That is the space in which compassion can arise.

Bodhicitta , Aspiration and Honour:

Q: You talked about compassion or bodhicitta being activity. Isn’t there something called ‘aspirational bodhicitta ’ – aspiration as the activity?

R: Aspiration is always a movement from one position to another, so it is always considered in terms of action. When I was young there was a certain type of aspiration going around – who wanted to write a book, or who wanted to travel to Antarctica. No one ever did anything – that was one kind of aspiration. Marijuana smokers are fond of that kind of aspiration – they tend to talk about all the wonderful things they are going to do, and never do them. Aspiration, if it is real, is linked with something with a direction and prompts movement. If it is connected with something vital, then to make that aspiration is important.

That is linked with the topic of honour. Honour is an old-fashioned term. Honour, promise – it existed in societies once. Now everything is ‘process’: ‘Well, I know I said that; but I’m in this process at the moment, and I don’t say that anymore’. Not that there is anything wrong with process; and promise can be stupid – I can promise something stupid, and then be held by a promise that was made out of ignorance . Obviously, promise is not the thing, and process is not the thing. Promise is form , and process is emptiness . If someone can really live by process, then that is fine; but you often find that people who live by process are not open to other people’s process. They will say: ‘But you promised!’ ‘Oh, well it is my process now’. If process is fine, then everything is process. Honour is important with aspirational bodhicitta , because the aspiration holds you to something. ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if I could do something for all sentient beings ?… Yeah, OK; I’ve made the aspiration. Now I’ll go have another hamburger – or whatever I’m going to do.’ And it is gone!

The sense there is that once I have made that aspiration and promise, I am tied to that. That is energetic – I have to do something. If you read history, there are inspiring statements about what people used to do on points of honour – interesting ! We miss out on that when we emphasise process too much. There was a wonderful part of a Robert Louis Stevenson story: It was after the battle of Culloden, and an English and Scots soldier meet each other in a barn. They are both burnt out, starving, and bleeding. They look at each other and think: ‘Oh, dear! What are we going to do now?’ They come to this agreement: They toss a coin – heads they are friends for life and share the food ; tails they fight each other. They toss the coin, are friends for life and share the food . And I thought : ‘That is good; I like that.’ There is something in that that people have lost. Like Robert E. Lee, fighting for the Confederacy because Virginia went in. He did not want to do it; but he had to. That position is interesting , when you think: ‘I am going to do what I do not want to do, because I have a loyalty here.’ That being held to a promise, that connection, involves bodhicitta .

Q: But if it is holding you, then aren’t you just doing something out of obligation rather than sincere motivation?

R: Sure.

Q: How do you deal with that?

R: Until you are fully realised, everything is mixed. Pure motivation is dreadful stuff – terrible business. It is better never to think: ‘I have pure motivation.’ To assess yourself as to whether your motivation is pure, and then to judge others on their level of motivation, is to enter a paranoid world . It is better to try to have pure motivation. If your motivation is mixed, then it is: ‘I’m doing my best. Sometimes I am donating merit to all sentient beings out of obligation.’ It feels like that – that is going to happen; that is realistic. Then you can say: ‘Yes, that is where I am at the moment – I don’t have a lot of space. I’m going to try, though, even if I have to force it through obligation; because I’m a practitioner, I’ll do that.’ That is to realise that one moves through many different circumstances. Sometimes it is obligation, sometimes it is joyful, sometimes it is a mixture, sometimes it might even be enlightened activity – that might sparkle through. One might do something, out of the blue, and think: ‘Whew, I did that! That was interesting – I never did that before. I let something go, just for nothing there.’ That can always happen. What is important is having a compassionate relationship with oneself.

I always remember when I lived in Cardiff, there was a doctor who used to have an interest in various spiritual things. He went along to see a Lama one night who gave a talk about how it was important to care for yourself, to love and feel good about yourself, as a basis. He was impressed with this. A couple of weeks later I was giving some teaching at a Gélug Buddhist centre; and he asked if he could come along and meet the Geshé there. We had a cup of tea together, and the doctor said: "I was really impressed by this Lama last week who said that you have to love yourself." The Geshé said: "No, no! You must love others; not yourself." This disturbed the doctor, who perceived this big conflict here. I said: "Geshé-la, maybe I should explain. The Lama who made this comment, I think, made it on the basis that a lot of people in this country don’t like themselves – some people hate themselves." He said: "Really? Oh, then in that case…" He had never come across this concept. In Tibetan culture it is taken for granted that you think that you are an alright guy; so everything is directed to others.

I was with one of my teachers, Kyabjé Chhi’mèd Rig’dzin Rinpoche , in Germany. He was talking about tonglen , giving a whole teaching on giving away all self -benefit and taking on the suffering of others, as an internal process. I could see the audience looking more and more depressed. Suddenly one woman said: "I can’t do this!" He looked at her like she was a piece of cheese or something, and said to me: "You answer this." I had to explain that, in the Tibetan culture, bodhicitta is macho. It is not like I take on the sufferings of others; and there I am crucified, up on this cross, getting cancer and shrinking into a cinder. This is what we perceive as the result in our culture. That is not how Tibetans see those teachings. For a Tibetan it is chest-beating: ‘I am going to be a Bodhisattva . I am going to save beings; because if I am a Bodhisattva , I can take it. Give it all to me. I’ll take it, and I’ll give everything away…’ It is a whole different attitude. We are not used to that idea of suffering – taking it on. In terms of aspiration, it is also that I become strong enough to do this. When I recognise the emptiness of phenomena , the emptiness of my concrete existence, then what is there to suffer , anyway? It all goes into emptiness . Gone!

Q: I have heard that tonglen is most effective when shi-nè has been stabilised – it has to be a foundation. How effective is tonglen if we don’t know how stabilised our shi-nè is?

R: Shi-nè or shamatha is the ground of everything; yet both can be practised at the same time . It is not that one has to come before the other – one can have both practices, and practise them in tandem. If one is running into problems with tonglen , then one can emphasise shamatha or shi-nè – practices are methods. This relates to the topic of whether practice is linear or lateral, whether it is sequential or non-sequential. Shi-nè can be practised in many different ways. One can practise attitudinal shi-nè – the emptiness of one’s experience, letting go of reference points. One can do that in the middle of an argument, in terms of letting go: ‘Maybe I’ll let go of being right; and see what happens.’ There are many ways of approaching that besides silent sitting – although it is important that silent sitting is integrated into one’s everyday life . One has to practise shi-nè in other contexts. That is also what makes compassion possible – that one makes space in which one can appreciate the other person.

Bodhicitta and Bravery:

Q: Rinpoche , you talked about the energetic quality of bodhicitta . It seems that energy has something to do with intelligent bravery – some quality like that?

R: Absolutely. One cannot talk about compassion without wisdom – the two always go together. In order to have compassion one has to have intelligence. In order to allow intelligence to function, one has to have bravery. That always equates with the three Bodhisattvas – Chenrézigs, Manjushri , Vajrapani – compassion , wisdom , energy/bravery. One cannot have compassion without intelligence; because intelligence allows it. This is one of the things that always gets in the way of compassion – one’s lack of understanding, or one’s fixed state. When my little son, Robert, throws up on me, I am not angry with him. But if we go out to dinner, and you drink too much and you throw up on me, I may have a different attitude – because I attribute greater responsibility to you. Then I say: ‘Maybe he is having a bad time at the moment. How bad do I feel about this?’ A problem happens when someone stops being a babe-in-arms, and you begin to attribute more and more responsibility – until someone is an adult. Then you assume because someone is an adult that they have your level of responsibility; and if they do not, then one judges them according to some criterion – and compassion is not possible then. The interesting thing here, that Western people do not like—those that are addicted to democracy at all costs—is that people are not equal. If people are equal, then compassion cannot exist. It is their inequality that allows compassion ; because if everyone is equally responsible for their acts, then how can you be compassionate ? You have to judge them; they know what they are doing. This is the way the criminal system works. It is not that someone has a deep problem, which is why they are doing what they are doing. Compassion rests on inequality – on recognising that. I recognise my son does not mean to throw up on my shirt. It is interesting , that because people are all adults, they are all seen as equal. Now, when I say people are not equal, I am not saying they are not intrinsically equal – they are equal as enlightened beings, as beings. But in terms of their capacity, they are unequal. One has to recognise that and say: ‘What is the condition of this human being who is treating me in this way?’ I am not a great exponent of the ‘Bible’, but that is an interesting thing that Christ said: ‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.’ Not: ‘Father, forgive them; because I am a really great guy and I don’t mind.’ That is important – they do not know what they are doing. That is why one forgives people; because they do not have the capacity or knowledge . They are acting out of ignorance ; they are acting out of pain. If one perceives that, where someone is coming from, then how can you be angry? It is as easy to be angry with a child that is just reacting, as Robert throwing up. And people do the same thing emotionally .

Bodhicitta in Response to ‘Wilful Evil ’:

Q: This raises a difficult question for me: can there be compassion in response to wilful evil or—for lack of a better word—wilful destruction? When you actually assess someone to be acting out of bad interest ; where there is intelligence, but there is also willingness to actually manipulate, use and appropriate people for one’s own interest ? In the Buddhist tradition , can one meet that with bodhicitta Because we’re talking about someone who can assume responsibility, but has chosen not to.

R: That in itself is an incapacity. You see, intelligence is over-rated. There are two kinds of intelligence – there is intelligence/prajna which is an open quality of intelligence. Then there is a constricted form that can be highly ‘intelligent’ in a commonly understood way, which can be distorted. In my couple of years as a therapeutic counsellor in Cardiff, I met a lot of depressives; and they were all intelligent. They were so intelligent, they found an answer for everything – so the intelligence there was sick. At the level of sociopathy to which you are referring, where someone is apparently acting deliberately, there will be a reason – it is that they have a paranoid world view. It comes out of having to safeguard oneself at all cost. Inside that person you will find someone terrified, even though they are hiding it. Now, one might have to protect oneself against such a person – that is for sure.

Q: An extreme would be a hit man; that would be on the inside a paranoid view? Would that actually warrant compassion – from a Buddhist view?

R: Yes. Consider that whatever I am prepared to do to you, or anyone, I then have the imagination that that can be done to me. I cannot be a hit man without a concept of being a victim of a hit man; because that is part of my world view. Whatever I am prepared to do to others—cheating, swindling, killing, torturing—is there in my imagination as possible for me. The greater kindness I have for other beings, the less I am prepared to damage other beings, that is what I see in the world . Even if something else happens—even if I am badly treated—it does not affect my view that much, because that is my dominant view. This puts one into a terrified position. The more you do to others, the more dangerous you have to become in order to protect yourself. It is completely paranoid; it is a completely brutalised environment. That is a great cause for compassion – seeing that brutalised existence and the level of fear that is hidden there.

Q: Rinpoche , in relationship to the question about a person who was deliberately inflicting pain or violence on another person… I am confused. You could have several different approaches. You could have someone who is conservative say: ‘What is the compassionate thing to do? [break in tape] … that we understand that there is fear there and that we love them. So we have two different people operating from the viewpoint of compassion with two different resolutions to a real problem?

R: You do not have to hate the person from either perspective.

Q: No, but yet you have to act. There are two separate ways of acting here, with the same notion of dealing compassionately. The liberal person would look at the conservative and say: ‘No, that is not compassion ’. And the conservative would look at the liberal and say: ‘Well, that’s not compassion , either – the best thing to do is this.’ How does one resolve things like that?

R: By not being right.

Q: But yet you still have this person that is making us have to act in some way.

R: That is called ‘being alive’. One acts according to many different factors – and there are often aspects of things we have to do with which we feel uncomfortable. Not feeling justified in whatever action one takes—not being right—is important. As soon as you say: ‘OK, that had to be done. I am completely right’, then you have frozen something. That is where bodhicitta dies. Actually, what your act is in the end is not as important as allowing yourself to remain confused about it. To say: ‘I don’t know – I did the best I could in those circumstances, with whatever knowledge I had and the constraints there were around me.’ And not to judge others for making different decisions – that is all you can do. That is important. Looking for a right answer that you can just ‘do’ because it is right, is tricky. As soon as I am right, I close off; I act mechanically.

Q: So the bravery we were talking about is the possibility that you are going to screw up?

R: Yes. That is important.

Q2: Going back to form and emptiness , the bravery can actually be a manifestation of emptiness ; and it can also be a manifestation of form ?

R: Yes, it has to be.

Q3: In the realised state, does a certainty arise? Or are you still uncertain?

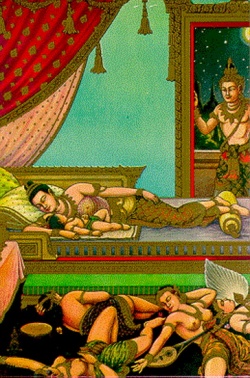

R: I would wait till you get there. In terms of the question of why people do what they do, and issues of crime and punishment, in Britain there is what is called the ‘bad or mad’ debate . That is, there are those who want to call people bad and want to punish them; and the others will say they are mad in some way, and want to look after them. This is interesting to consider in terms of its philosophical core. When we approach Buddhism , Judæo-Christian constructs can be quite prominent in terms of what we do, and accept and interpret. We could consider the idea of freedom of choice – whether it exists and how it exists. From a Buddhist perspective we would say that we have choice and we have no choice; it is tricky. There is always choice that occurs in terms of exhaustion; when our strategies fail completely, we have a moment when we can reappraise the situation – there is space there in which something can happen. That is why we engage in silent sitting; so that we can find space in which neurosis can unravel itself. This will happen whether we like it or not. It is called life -crisis; it is called illness, some unexpected incident, maybe seeing something beautiful, something ugly, something surprising… We have these possibilities – these moments when choice can actually exist. Most of the time we have little choice, indeed; because whatever choice I make is built on previous choices I have made. When a discussion of karma and motivation is held, someone usually seizes on the idea that there are people such as Hitler, who are essentially bad, evil , and beyond the pale in some way. This is completely antithetical to a Buddhist view; no one is like this. This is why we have the story of Rudra. Rudra means massively screwed-up; complete ignorance , but forceful ignorance . It is a kind of folk tale, and an important one. It is about two students of a certain teacher , who are instructed that everything is essentially perfect – complete in its own nature. One goes away and becomes a hermit and practises. The other goes away and becomes a bandit – a great bandit. The two students meet one day and are talking about the nature of their practice. They become aware that they have slightly different angles on practice. This concerns them somewhat, and so they decide to go see the teacher . (You can tell it is a folk tale, already.) The teacher says to the bandit: ‘I think you have misunderstood something here,’ at which point the bandit becomes angry, kills the teacher and his co-disciple , and goes on to become an even greater bandit.

Through his one-pointedness as a bandit, he achieves rebirth in the god -realm ; but he achieves it in such a way that his mother dies as soon as she has given birth to him. (What his mother did to deserve this, I do not know. That is not part of the story.) He is a hideous-looking being. This is interesting in itself – when you look at what power is, the only way you can become really powerful, is to become one-pointed in a samsaric sense . You have to be prepared to ‘ice’ anybody; you cannot have any friends. This makes you intrinsically ugly. So here he is in the god -realm , and he is this hideous being. The gods throw him out, because he is a disgusting sight . He lands in this great charnel ground, filled with corpses and stuff that is rotting. The first thing that Rudra does is eat his mother; then he starts to eat everything else. He becomes immensely powerful and able to kill everything that he finds – on the principle: ‘It exists; therefore I kill it and eat it.’ He dresses in all he finds around him – tiger-skins, elephant hides, human hides, bones.

Meanwhile the teacher and the other student, who are Amitabha and Chenrézigs, observe what is going on with Rudra. They decide they have to teach Rudra a lesson he will not forget. Amitabha manifests as a horse, and Chenrézigs as a pig. They humiliate Rudra by entering him through his anus. One explodes out of the top of his head as a horse; the other explodes out of his side as a pig. Then Rudra says: ‘OK, I am humiliated. I now dedicate my form as a method of practice – to display that however bad you are, you can be transformed.’

That is a crude folk story; but what it depicts is that there is no such thing as someone who is completely evil – that cannot exist in a Buddhist paradigm. There is only ever confusion. And however distorted the confusion is, it is still a distortion of enlightenment . Hence the wrathful awareness beings. They are a powerful method, because they display a compact description of negativity. They press all the buttons. You have Palden Lhamo who sits on the flayed hide of her own son. She carries loaded dice; because when she plays for the teachings, she always wins. Everything around these beings is corrupt, rotten – they carry sacks of diseases; they ride through oceans of blood. It is a nightmare, and it is the nightmare of our neuroses – that they can always be transformed. If someone had a vision today of a wrathful awareness being, he might have this mudra [gestures]. He might have this little moustache and a bit of hair that comes down… and we might say: ‘Oh! That’s a really bad thing there!’ If that can be transformed, if this is a symbol of enlightenment , then even I can become enlightened . This is powerful.

How do we apply this in our own lives in terms of what we do? In terms of how we approach our own motivation? This is most easily understood if we look at the idea of a shifting experiential norm. Picture your current motivations, ideas – the parameters of what I can do, what I cannot do, what I should do, what I should not do – the things that make up what you are. The cheesy things that I might do; and the things that are too cheesy for me to do. You can build a circle out of that. Everyone would say: ‘Yes, he or she would do that, under those circumstances.’; or: ‘That would surprise me, if I heard that they had done that.’ We all have an idea of each other, in terms of the actions we are capable of taking. When it gets toward the borders of what we will and will not do, there is a fuzzy area – an area we are always looking into, depending on what is happening to us. We can stray over that area occasionally, when we are hard-pressed by something; and we do something that we might regret. But if we do it enough, it becomes ‘normal’ – anything we do enough becomes normal. As soon as it becomes normal, then we extend what we are capable of doing – because our fuzzy area moves further out. So we do something else in that fuzzy area, in the same direction . You can imagine these little points. You then get a ruler, you connect up these points, and you see where they are going. It is like a map—I keep walking into this uncharted area; it keeps feeling normal—and I am going in a direction . You draw a line; at the end of it, you get Hitler, or you get Charles Manson, or you get whomever.

What is a person doing, who acts in a highly negative manner? It is interesting , in terms of understanding the nature of samsara , that we always justify whatever we do. If we have to do something that is unpleasant, then we create the world -view that supports that, with us in it: ‘Sometimes I just have to do this, because it is necessary for my protection… and that wasn’t a good person, anyway! They had it coming… If it hadn’t been me, it would have been somebody else.’ As this view evolves, this view makes me capable of doing other things, and I evolve a view around that as well—some kind of a world order—because the one thing that samsara is, is intelligent – intelligent in the sense of being able to conjure with facts and make them fit anything. It is extraordinary that, if one is discussing anything with a person who has a corrupt intelligence, they can justify anything.

This is not particularly esoteric – you can look at politics for that! Politicians all sound reasonable; and we all exist as politicians within ourselves – we create the agendas, and we conform to them. How long do you live with a bad thing done, before you come to terms with it in terms of how I am going to change myself, so I am not going to do that; or how it was perfectly OK to have done that? We move in one way or another. It is the process of making it OK that creates greater and greater complexity. Whatever I make OK in my actions is no longer outside my territory – I can move in that direction . I start evolving the skill of making things OK; I have made one thing OK – I know how to do that. I have not really observed myself doing that, because it is a process in which I am involved, in which I have to feel comfortable with who I am and what I am doing. A whole philosophy emerges. I may not be aware of the philosophy , but it is building up. It has a logic of its own, and then I dwell within that logic . This is a definition of the realms . When we look at the hell realm , the hungry ghost realm – these are all systems of logic in which we can find ourselves. When we end up as a person who is actually calculatedly vicious, there will be a philosophy there – a system that has made sense of itself, in order that I can survive as this person in terms of feeling OK about myself.

Q: In Buddhism we talk about the four strategies of pacifying, enriching, magnetising and destroying. It would seem that when someone has gone to a certain extent in cultivating their scheme, and solidifying the validity of what they are doing—when by ordinary standards that appears to be so dysfunctional—it seems that society’s response needs to be the destroying action, so that they cannot perpetuate what they are doing. To make it more personal, in response to relations with our bosses, our spouses, our neighbours—when we are confronted by highly dysfunctional, destructive kinds of actions—would that also be a statement of compassion , to exercise, in the Buddhist sense , a destroying strategy?

R: The Buddha Karmas of pacifying, enriching, magnetising and destroying, are exercised by Buddhas . In particular, with destroying, there is an awareness of consequences. For ordinary people such as ourselves, destruction can be applied to making things evident. I think that is the thing people do not like to do – to actually call what the game is. Instead of acting as if it is not happening. It is interesting to say: ‘Right. I am going to spell out what is happening here.’ That you could call destroying; because it is destroying the secrecy, the covert quality, the hidden agenda. A lady I once knew worked in a college in Britain. It was a rather strange institution, because it had been converted from one style of technical college into a place of higher education. It was full of under-qualified people who were now trying to act as college lecturers. They had a great resentment against newcomers who had higher qualifications – especially if they were women. The head of the department liked punctuality – because you were paid to be there from hours x to y, and you had to be there. That was his way of maintaining control and being the head of department. It was a primitive level of working; because in any college lecturers come and go – they are there for their classes. It is assumed it is an adult environment in which everyone does their work; but he was operating more on a factory level. He would say to her: ‘I was looking for you at 9:30 this morning!’ And she would start explaining herself. I said: "I do not think this is a good thing for you to do. If you want to work with that, you say: ‘Oh, really? What did you want?’ and make him spell out what he was saying." Because he was not prepared to say – he was a bit embarrassed about imposing this edict, too. To actually make him spell it out: ‘Where were you?’ ‘Oh, I think I was in the shower, actually.’ And next? And then after a while you would say: ‘Is this some way of telling me my work is not good enough? Have you got a complaint to make? What do you actually have to say to me?’ What she would do instead is start flapping, and making excuses around it; instead of saying: ‘Say what you mean. Let’s have it all out in the open. If you have something real to say, say it. Do you want everyone in at 9:00, whether they are working or not? I could be at the Xerox shop; I could be anywhere. If you have some idea I am not doing enough work, tell me.’

That is a principle of destroying things – of destroying what someone is setting up. There are all kinds of ways of doing that. And it is a slightly fearful thing to do, because one is aware: ‘This is my boss here.’ That should not matter – you are a human being, and people should be straight with each other. If someone is using some form of manipulation, you can simply destroy that by being fearless – by being OK, let it be as bad as it is going to be; because it is that bad anyway. That is important – it is as bad as it is; hiding from it is not going to make it any better. You say: ‘Have you got a problem? Are you dissatisfied? Tell me what you are dissatisfied with?’ She did that; and he completely backed down and disappeared. She was surprised. I said: "Yes, he is actually cowardly; that is why he approaches things in this way. He won’t say: ‘I want all of you in by…’ If he really means it, put a punch-card in there. Make it work like a factory then – demand that; but he is working in a sneaky way."

Compassion is being able to do that without being angry with the person. You realise: ‘This is the person’s situation; this is how he operates. And it must make his life miserable; because people do not like you if you do that to them.’ If you make someone dance like a monkey through your crafty language , they do not like you for it. This man cannot have a nice wife – he probably relates to his wife and children in that way, too. The problem is it cannot stop. The sense of kindness is important in the process of destroying. I would call that destroying, because it is destroying a system. One cannot approach it as an adversary; one can only approach that with a kind view of saying: ‘I’m not going to find this comfortable, and you are not, either, because it is exposing what you are doing; but I am going to have to do this.’ If one does this from a position of kindness, of not hating the person who is doing this because we know that this is all they know how to do – this system has worked for them for a long while, and no one has called them on it, and it is a pity; because this person could have a happier life if they were not doing this. Then the other person picks up that you are not hostile; you are just not playing that game.

I gave a talk. And there was a man there who walked in off the street. He was the most hostile man I had ever met – he was quite extraordinary. He ended up threatening someone with a gun he had in his pocket in the shop. He did not actually pull this thing out; but he insinuated that he would call somebody out and ‘waste’ them. I had asked if there were any questions. He started off with this long rigmarole: "So, what is it that makes somebody who wears a costume and gives a talk any better than anybody else?" I said: "I do not know." He said: "You really don’t know?" I said: "Your guess is as good as mine." You could see him thinking : ‘Ah, that wasn’t a good time . I was expecting an answer of some kind. Like why aren’t you defending yourself?’ So he just stopped – that was it. Then, unfortunately, somebody in the audience told him he was rude to me; which was just what he wanted, because what he wanted to do was fight. He stood up and grabbed the person by the coat. Then other people gathered around, and he was threatening to waste people; he really wanted to do something. That was an interesting picture. I was standing there, observing this and thinking : ‘What am I going to do if he makes a move for his pocket? I am just going to have to jump at him, because he might hurt somebody.’ So I was waiting there poised. Then the owner asked him to cool down, and he left. I thought : ‘That is a relief.’ Working with that – with some kind of aggression that comes up… I felt sorry for him. I thought : ‘You must be in a great deal of pain to be acting in this way.’ He came to this talk, and you could see he was not interested all the way through. He simply wanted to engage. This happens in relationship. When a relationship is breaking down, when one person is leaving, usually the one who is being left will enter into argument and start rows going. Violence is a form of intimacy; if we cannot cuddle, we can shout at each other. A lot of people do not understand what that is; and that is interesting . People who are trying to instigate violence are also trying to instigate intimacy. Violence is intimate—you get to touch people—even if you are hitting them, you are making human contact. It is a distorted method of having contact with people.

Q: You were saying that with the Buddha Karmas , the Buddhas choose a strategy or activity based on the fact they know what the result will be. But it seems we do not really know. It is all experimental. We have to do something – we have to act, so we pick a strategy. All we can do is have the right motivation?

R: It is a sliding scale: The more extreme the action, the more knowledge you need to have – with anything. Düd’jom Rinpoche often said: ‘Doing good is difficult; begin by trying not to do harm.’

Q2: When I first heard that, I thought that was kind of pathetic. But now I understand that. I had thought it was easy, not doing harm. But now I realise that it’s not so easy.

Q: You have started out with extreme examples of behaviour and violence, like Hitler. I have a reaction to that when I see it on television or hear about it. One would think from a Tantric point of view, I would be able to work on myself; but what happens is a nebulous anxiety – I go paralysed. I have nothing effective to deal with it. All I can do is shut it out and then continue what I’m trying to do that is positive. It’s definitely affecting me. And I would like to know what I can do – it’s an overwhelming anxiety.

R: As a practitioner, one has to say: ‘Nothing affects me; I affect myself in relation to something.’ It is always me – it is me that is creating the anxiety with relation to… I think that one has to make friends with Hitler, in some way.

Q: Why?

R: Because I am Hitler.

Q: I don’t agree with that.

R: Well, you are Hitler, too. Everyone has the capacity to be Hitler.

Q: No, I don’t think so… I don’t.

R: Then you are a really dangerous person. If you think you cannot be Hitler, that is why you are frightened; because you believe somewhere that you are, and you are trying to shut that out. That is dangerous.

Q: I am not afraid to go into that. But I do not believe that that is true.

R: Why?

Q: I don’t want to…

R: Sure you do not want to; but that is really important.

Q: On the other hand, if that’s true, I would really want to know that; because something could be done about that. I mean, I could get upset, and I could raise my voice and show something; but it is still not a Hitler act of creating concentration camps and…

R: No, you have to look at how you operate the final solutions in small ways. We are talking here about a continuum, this experiential drift. It starts somewhere. Hitler did not just appear and say: ‘Hey! Concentration camps – let’s murder people!’ He had to be rejected at art college first, he had to do stuff, and he had to get a lot of support in doing that. It is a gradual process. It is important that we accept that we could go that way; maybe over a long period of time ; maybe not in this life ; but maybe, who knows? It is tricky. One has to own that; that is important. Otherwise, we are the good guys; and they are the bad guys out there.

Q: When seeing these things on TV, it ends in a nebulous, foggy thing that I am unconnected to; I could start trembling… And what would I do? I would undermine myself, and I would kill parts of myself, right?

R: Yes.

Q: Right. I saw that I would do that; and so yes, that is dangerous.

R: You have to create a balance in terms of how much you expose yourself to looking at stuff. I watched a series on the American Indians and the push West. It was the most depressing thing I had seen for a long time . I thought : ‘I am not going to watch that again in a hurry,’ because one empathises with people. You think: ‘That is a serious thing to see’; but it is important to understand and be linked with that, and not be cut off from it while it is happening. Maybe you need to limit how much you see it; but while you are seeing it, it is good to look at what people are doing and to try to understand their position. I saw a film about one of the Nazi extermination camps. That was a horrific film. There was an interesting part, where the commandant and the second in command were looking at jewellery that these two young Jewish goldsmiths had made. They were admiring the fine work. The two lads said: ‘When do we get to see our parents?’ The second in command just hit him around the face. The commandant said: ‘No, no. Don’t do that. You’ll be with your parents soon.’ I said to the students there: ‘What did you make of those two men? Who did you think was the worse of the two?’ They all said it was the person who struck out. I said: ‘No, he was a lot more human; because he was having to distance this person. The other was completely out there: ‘You’ll be with your parents soon’ – you are next in the gas chamber. He was completely removed. You can see that as a process; you only have to do that enough in order to completely disconnect yourself. What is important is to look at the small ways in which we disconnect ourselves. It is not that you have to imagine yourself gassing people. It is how you disconnect, even at a small level; and say, ‘How do I disconnect in my life ?’ If I start disconnecting, then I could be like Hitler one day—because he is totally disconnected—and that is the end of the line. How we work with it, is that we have to look at how we disconnect from other human beings, from other animals , from situations – that is so important!

Q: Would you say that is also good material for tonglen practice? I find that during tonglen practice, using or bringing up people that I consider my inner-nature – that that is a good way to use that, to do something.

R: Absolutely, yes; but here it is important to try to understand how someone got to where they got – especially if someone is doing something vicious to you. Obviously you cannot enjoy that; you think: ‘I wish they weren’t doing that.’ It is important to realise that in some way they have a rationale for this – it makes sense to them. That should be horrifying, in a way. You do not hate that person; you think: ‘I am lucky that I don’t have that rationale. But what reflection of that rationale is there, at a milder level, in how I am?’ The act of compassion there is to reflect on me and say: ‘I don’t do that; but what do I do that is the thin end of the wedge of that?’ You become part of that. You do not disconnect from that person: ‘This is a person who does really bad things; and I am a person that doesn’t.’ One has to accept the continuum there: ‘In smaller ways – maybe in microscopic ways – I do that.’ That is important.

Q: Is it that we are talking about the need to establish proper boundaries? That there’s a way through practice that we establish boundaries? Trungpa Rinpoche would say: "There’s some feedback." We get feedback about our actions; and we work with other people so they get feedback, too. Maybe in some sense , America’s vast country and the lack of boundary allowed us to go too far and commit atrocities – especially with the Indians. It seems to me as practitioners we have a container with our practice; it’s important to establish this container. We have this anger – this possibility of being outrageous. It’s like nuclear fusion, isn’t it? How do you hold this vast energy? You are afraid to let it go. How do you open up and let go… a little bit? I personally can get pretty angry; and then, how do you express it?

R: The most important thing is to avoid using a method of any kind. All we ever have is the moment and whatever our capacities and perception are in that moment. One can only allow what happens to happen, and have awareness so one can feedback quickly on what is happening. Also to allow oneself to be destroyed – in terms of my concept of who I am as a good person, a good practitioner, someone who is doing it right. To say: ‘I am involved in something crazy at the moment. I am going to just let the whole thing fall apart, and start again.’; to be able to exist in chaos, a little bit more.

Q: Lama Tharchin once said that his guru received instructions from his own guru , Lama Shérab Dorje , to totally stop practising a yidam practice for a year. So they all went away; and they all came back the next year, and he asked: ‘Did you stop practising?’ And he kind of looked away, because he hadn’t really stopped. ‘That’s the problem! The people who should be practising aren’t; and the people who shouldn’t be practising are.’ I appreciate that… you have to let go completely.

R: Yes. To follow a rule that governs anything apart from awareness and kindness is problematic. At some level, wanting to apply a method becomes problematic, because it is a way of not allowing awareness to function.

Q2: Rinpoche , how does that relate to how your actions should be based on what you want the result to be? Don’t you set yourself up with a methodology or a strategy for achieving that result, rather than being more spontaneous? By having a direction you have to go in?

R: Spontaneous is a funny word.

Q: Well, if you don’t have a method, then you respond to a situation…

R: You see, kindness or compassion is its own method. It is empty method because it takes endless different forms ; and its application functions through awareness . One does not have to have any strategy. In the example of the lady sending the letter to her friend, I said: ‘Just think about your friend – where she was coming from, and what you could say that might be useful that is going to allow you to retain the friendship – if that is what you want. Maybe just express some pain; be vulnerable. One can allow some intuition to function there. One has the situation; and one is aware of the tension of what one wants to do. I think you are talking about a slightly different thing here. It is not some goal orientation of: ‘What do I want it to be? Therefore I work towards what I want it to be.’ But we are talking here from the point of view of kindness; and I am presupposing one is wishing a happy result for all concerned…or what am I trying to protect here?

Q: This is where it gets sort of cloudy – in understanding that what one wants from a situation is based on one’s motivation; and if one’s motivation is selfish, maybe one isn’t acting with compassion .

R: Well, there is nothing so terrible about selfishness – if it is intelligent.

Q: But if it is for some gain or manipulation of the situation, then one isn’t acting with compassion or wisdom . Because one is acting for oneself entirely, rather than looking at the other person or the situation.

R: Acting with wisdom and compassion is what one does as an enlightened being. So one can forget the concept of acting with wisdom and compassion . ‘Am I acting with wisdom and compassion – yes or no?’ Yes is dangerous. One can be aware of one’s own tension in that situation. Like, what do I want out of this for myself? What do I need to let go of here? This has to happen – I have to say this. But how can I put it across in a way that is not brutal? That is always difficult. You cannot have a plan of action. You say the first couple of words, and the person replies; and that throws the plan into chaos immediately. It is not like that. You are looking at the person… which is why e-mail is tricky. You just hit the ‘send’ button and ‘whoa!’ off it goes, and you cannot get it back. At least with a letter, you have got to walk to the box. Then if you let go of it, you can sit till the postman comes and say: ‘Look, here is my ID. Please give me this letter back.’ But with that button, ‘Whoop!’ It is gone. It is in Canada or Australia immediately. That is really tricky. In terms of compassion , one has to value one’s own compassionate propensity. Be prepared to not be comfortable – to not know how it is going to work out when you start the sentence, or what you are going to say next. To actually just be in space, and be out of control in a sense – not out of control like being wild and shouting; but just not knowing how to cope. Looking for some answer there; but realising it is a chaotic situation. Being content to let the situation evolve, maybe in surprising ways. It is a open field, really. But if you try to control everything, and make it go a certain way… compassion is certainly not always about dominating a situation, even for the best. It is being prepared to enter chaos, allow things to form at their own speed. This is linked with the Buddha Karmas , in terms of enriching, pacifying, magnetising, destroying. Everything is moving at its own speed. Actually trying to help anybody is difficult; because for anybody to actually change, they have to be open to changing.

Q: So often in relationships, it’s not being afraid to let go of control. Often we want to think that everything will come out according to our perception of what’s going to be beneficial. But you don’t know the other person’s perception . And you have to step back from that, and let that space be there. Because without that, nothing is possible. You strangulate everything.

R: Yes. It is hard; because if you look at what you get out of control, it is actually narrow. Unless I think that I am the best person in the world , and that my idea is really the best idea – that is somehow depressing! It means that if I get my way, the world will be as good as I am. I would prefer it to be better than that somehow – to be surprised by more interesting things than expanding me all over it! Someone might have a better idea; and I might enjoy that more than my idea. This plays into romantic relationship, especially. When one partner dominates, that is crippling.

Emotion

Enlightened Anger – the Liberated Emotions :

Q: You said that one should have compassion for people who act in a negative way; and also that you can be enlightened and have anger . Is that anger a transformation of that energy, that doesn’t confound you on it?

R: We could start by looking at the essential part of what kleshas —the Five Buddha Families —mean; what these neuroses are, how they are transformed. In order to have compassion you have to have understanding. There would be a simplistic level at which one could say: "Oh, this is a nasty, cruel person who is acting in despicable ways. I feel sorry for them because I am trying to be a good person; and part of the rule book of being a good person is to feel compassion for those who aren’t, because in some way they are going to suffer for it, etc. etc." That is hard to maintain; because there is no reason for it in particular, apart from the fact that ‘this is the correct way to approach it’ and I want to be correct. I think this is one of the problems of Victorian morality – that you simply did not do certain things because it was ‘immoral’; not because you understood why. That is a reason why a lot of morality disappeared, especially with regard to sexual relationship. One cannot simply follow edicts because they are holy or moral ; one has to understand why they function. In terms of having compassion for others who express anger , paranoia, greed , obsession, wilful stupidity – one has to see them in oneself. That is important. If one cannot see them in oneself, one cannot have any compassion . One has to have some degree of clarity. One has to say: ‘How do I cause myself pain with this? How have I caused myself pain in the past, and how have I got greater clarity now? Although this is still manifesting, it is not riding me. When I see another who has got that thing riding them, then I can say: "Whew! If I could do anything to help that person out of that, I really would like to; because that is a terrible place to be. The place I am is not much better; but that is a worse place". There is a direction – as much as I wish to be out of that, I wish everyone else was out of that too. One sees it in oneself and one understands it.

There is an important point about samsara in general: there is only one thing wrong with samsara – samsara does not work; that is what is wrong with it. It is not that it is naughty, evil , bad, wicked or whatever. It does not work; in its own terms it does not work. Until one discovers that samsara does not work, one will continue to ‘do’ samsara . The basis of compassion is realising that samsara does not work. That is so poignant – because even when you realise that it does not work, it is still worth a try! Somehow, we still go through the motions of it, saying: ‘Yeah, I’ll give it another shot, even though…’ You think: ‘Maybe I’ll get away with it once; and I will actually get what I want and it will be great.’ Then you think: ‘Nah… I did it again, didn’t I? And I knew it would be like that.’ That is tragic – and humorous too; and it is that ambivalence that breeds compassion . Otherwise you would look at other people doing samsara as being stupid – you would despise them for their weakness for doing samsara when ‘I am on the way out’. But there is humour there; because you can see that there are brave and noble qualities involved in beating yourself to death with samsara ; it is charming in some ways.

One has to understand the living texture of that situation. That is in terms of answering your question about compassion . Looking at what ‘enlightened anger ’ is, one has to understand the process of samsara . In Tibetan we use the word ‘khor-wa’, which means going around in circles – this is a self -defeating circle. One has to understand the manner in which the circle defeats itself. This can be an explanation of any of the five elements. You named anger ; so we will have a look at that one. All of these ‘negative’ emotions have a root, which is a reaction to the experience of nonduality . We start from the basis that we are beginninglessly enlightened . Unenlightenment is the effort to hide from that; because we have misinterpreted the enlightened state as a state of non-existence. Because we are beginninglessly enlightened , that state cannot help but sparkle through – it is the real state, nonduality . Whenever that sparkles through we have a moment in which we are free – not free in the sense of being realised, but we are free to move in one of two directions . We either move into experiencing that openness, or into retracting back into samsara and regenerating the process. These moments happen spontaneously, caused by all manner of things. They also happen through exhaustion. One can explore the whole quality of exhaustion when one looks at the six realms . The realms have to wear themselves out. And at the point of exhaustion one can either recreate the realm or one can move into a higher realm of being; in terms of the six realms , that is how that works.

One can see how samsara operates in each of the five elemental patterns. Anger is described as distorted clarity. The root of anger is fear – we perceive our enlightened nature, and we misinterpret it. We perceive it as a direct force that is out to obliterate us; so fear arises. We have to attack whatever we are afraid of; because we are being destroyed, we have to lash out in order to feel safe. This forms aggression of all kinds – from the mildest irritation up to various forms of genocide are all included within this aggression. This is why I say: "We are all Hitler." When I get irritated, I am on that track that leads to Hitler – one has to recognise that: ‘I can escalate this irritation. I can feed that irritation.’ This arises from fear. That is important. Whenever you see anyone who is acting aggressively, you know they are afraid. Then some compassion can arise, because you can say: ‘I am glad I don’t have to do that.’ I am glad I do not live with that tension of having to attack people, because they are different, or they remind me of something I do not want to know about or something in myself that worries me.

Q: The question arises because of a discussion I’ve had with someone, who works out of anger and fear quite a bit. And he says: "I’m going to work on achieving enlightenment even though it is there."

R: Being an angry person gives you something with which you can work. You sit with it. You do not act it out; that is important. There is a whole method where you sit with that anger arising, and you simply experience what that is like. You do not follow thoughts about it. There are many different things you can do—subtly different—depending on your level of practice. In terms of Dzogchen , one would find the presence of awareness in the dimension of the sensation of anger . You would locate that in your body as either in a place or as pervasive. You would find the presence of awareness in the dimension of that sensation . Whatever thoughts about the anger arose, you would not follow.

Now naturally, everyone in their own practice would be practising something different. Practising that at the level of shi-nè, there would be thoughts arising and one simply would not follow them. In terms of Dzogchen , you would not have that situation of thoughts arising at all – one would simply go directly into the sensation . Usually with a strong enough emotion , the emotion will burn up namthog in a certain way. In terms of Tantra , the inner Tantra practice of working with negative emotions is to arise as the yidam . If there were anger , one would arise as Dorje Phurba or Dorje Tröllö; in that anger you would become Dorje Tröllö and experience the anger as that. Here, once you dissolve subject and object of anger , you have clarity.

You can begin to create space in which you see the pattern of it and in which you can recognise that fear as groundless – as pure sensation . That is where you begin to work on it, or embrace it – that whatever arises, you simply become the sensation of what arises. Now if you look at anger , you can see within anger many qualities of clarity – it is intelligent, lucid. Whatever you say might be witty, sharp, sarcastic – sarcasm is often so perfect; you say the thing that humiliates the person in the worst possible way and it is just ideal. You have increased memory , loquacity – it is absolutely to the point. All these are qualities of clarity. There is crispness around fear and anger – hot anger or cold anger – it is the water element. The hot anger does one thing. With the cold anger there is this icy thing – it has these clear qualities of tension, sharpness. The enlightened state is that quality in the nondual state – which is clarity. Everything contains this compassionate reflex; because without clarity, compassion is not possible. It is seeing the situation to be exactly what it is.

Q: There is one situation if you’re angry; but there’s another situation if anger is being directed at you. If someone else was angry at me, okay then my response would be fear. And so there is like a dance going—anger and fear—that then could turn back into anger and aggression.

R: Absolutely. That is exactly what it does.

Q: I feel that I don’t have an honest, compassionate way of being in such a situation, other than fear. I am fear!

R: It is like dogs… I was a postman once, among other things, to earn money in order to travel to India . There were dogs; and dogs interpret fear as aggression. If you are afraid, it is not that: ‘I am a poor, harmless little thing.’ "Rrrghh!" They will go for you. There was this dog; I knew this one. One day he came bounding towards the gate; and I said: "RRRrrrghhh!" He looked at me and went: "Mmmm…" It was alright after that – it was fine. He even let me stroke him. It depends on the circumstances in which you are feeling the fear.

Obviously there are some circumstances in which fear is probably appropriate. And relaxing into it is – well, maybe that would not hurt either. If it is a physically safe situation, let us say, but you have got someone’s anger at work, you have to remember that they are frightened. There is nothing like someone being afraid that draws somebody on in their anger . People can get into a sadistic spiral then, of wanting to see how much they can brutalise you. They are afraid of it happening to them, and they are almost hypnotised by you as a victim – which draws them on to do more and more and more. It is a horrible trap – both people get trapped in that. Unfortunately, the only thing to do is to relax and to recognise that the person is afraid.

That is not an easy thing to do. One has to start by seeing it in oneself. It is a process; but the important thing is to remember. Always with teaching, one has to remember it in the situation; and one only remembers it if one has experienced it at the level of practice. When you feel fear or you feel anger , you sit with it and you get to learn about that. When you see it in other people, you know it might not have anything specifically to do with you. You think: ‘This is what this person is experiencing. Maybe I could deal with this in some other way.’ That has to be your experiment; to say: ‘Maybe I don’t have to reflect anger back; maybe I don’t have to protect myself. Maybe I can just hear this person out and wait for them to run out of steam.’