DEVELOP MIRROR-LIKE WISDOM

ANKUR BARUA, N. TESTERMAN, M.A. BASILIO

Buddhist Door, Tung Lin Kok Yuen, Hong Kong

Hong Kong, 2009

Abstarct

The Yogācāra school of Buddhist thought was founded by the two brothers, Asanga and Vasubandhu in the fifth century. The most famous innovation of the Yogācāra School was the doctrine of eight consciousnesses and it upheld the concept that consciousness (vijñāna) is real, but its objects of constructions are unreal. The key emphasis of Yogācāra is on insight meditation which is actually considered to be a means of abandoning delusions about the self and about the world. When the storehouse consciousness is finally transformed into the grand-mirror-like wisdom, it reflects the entire universe without distortion. This wisdom can perceive many objects accurately and simultaneously.

Key Words: Mind, Manas, Ālaya, Consciousness, Insight, Meditation.

DEVELOP MIRROR-LIKE WISDOM

Introduction

The Yogācāra school of Buddhist thought was founded by the two brothers, Asanga and Vasubandhu in the fifth century. Yogācāra was a synthesis created in response to all existing schools of Buddhism during the third century BC. Yogācāra extracted the common teachings from all the Buddhist traditions and made an attempt to resolve the problems that most of them were facing. The key epistemological and metaphysical insights of Yogācāra evolved from the common Buddhist belief that knowledge comes only from the senses (vijnapti). With a new insight, Yogācāra proposed that the mind, itself, was an aspect of vijnapti.1,2,3,4

Asanga further recognized that though the mind can sense its own objects, which are known as thoughts (apperception), but it cannot verify its own interpretation. As the senses are constantly misinterpreted, our thoughts (apperceptions) are also misinterpreted in the same way. These misconceptions are instinctive and nearly universal because they are caused by the desires, fears and anxieties that come with animal survival. This results in an automatic assumption of substance for self and objects (atman and dharma) which are created to suppress our fears.1,3,4,5

Various Types of Consciousness in Yogācāra

The most famous innovation of the Yogācāra School was the doctrine of eight consciousnesses. Early Buddhism and Abhidhamma described six consciousnesses, each produced by the contact between its specific sense organ and a corresponding sense object. Thus, when a functioning eye comes into contact with a color or shape, visual consciousness is produced. Consciousness does not create the sensory sphere, but is an effect of the interaction of a sense organ and its true object. If an eye does not function but an object is present, visual consciousness does not arise. The same is true if a functional eye fails to encounter a visual object.5,6,7,8,9

Arising of consciousness is dependent on sensation. There are altogether six sense organs (eye, ear, nose, mouth, body, and mind) which interact with their respective sensory object domains like visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, tactile, and mental spheres. Here, the mind is considered to be another sense organ as it functions like the other senses. It involves the activity of a sense organ (manas), its domain (mano-dhātu) and the resulting consciousness (mano-vijñāna). Each domain is discrete and function independent of the other. Hence, the deaf can see and the blind can hear. Objects are also specific to their domain and the same is true of the consciousnesses like the visual consciousness is entirely distinct from auditory consciousness. There are six distinct types of consciousness namely, the visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, tactile and mental consciousness.5,6,7,8,9

The six sense organs, six sense object domains and six resulting consciousnesses comprise our eighteen components of experience and are known as the eighteen dhātus. According to Buddhism, these eighteen dhātus are the comprehensive sensorium of everything in the universe.6,7,8,9

As Abhidhamma grew more complex, disputes intensified between different Buddhist schools along a range of issues. In order to avoid the idea of a permanent self, Buddhists said citta is momentary. Since a new citta apperceives a new cognitive field each moment, the apparent continuity of mental states was explained causally by claiming each citta, in the moment it ceased, also acted as cause for the arising of its successor. This was fine for continuous perceptions and thought processes, but difficulties arose since Buddhists identified a number of situations in which no citta at all was present or operative, such as deep sleep, unconsciousness, and certain meditative conditions explicitly defined as devoid of citta (āsaṃjñī-samāpatti, nirodha-samāpatti). So, the controversial questions were: from where does consciousness reemerge after deep sleep? How does consciousness begin in a new life? The various Buddhist attempts to answer these questions led to more difficulties and disputes. For Yogācāra the most important problems revolved around questions of causality and consciousness.6,7,8,9

Yogācārins responded by rearranging the tripartite structure of the mental level of the eighteen dhātus into three novel types of consciousnesses. Mano-vijñāna (empirical consciousness) became the sixth consciousness processing the cognitive content of the five senses as well as mental objects (thoughts, ideas). Manas became the seventh consciousness, which was primarily obsessed with various aspects and notions of "self". Hence, it was called "defiled manas" (kliṣṭa-manas). The eighth consciousness, ālaya-vijñāna also known as "warehouse consciousness," was totally novel.6,7,8,9

Four Wisdoms from Eight Consciousnesses7

(1) The first five perceptual consciousnesses are transformed into the Wisdom of Successful Performance. This wisdom is characterized by pure and unimpeded functioning (no attachment or distortion) in its relation to the (sense) organs and their objects.

(2) The sixth consciousness is the perceptual and cognitive processing center. It is transformed into the Wisdom of Wonderful Contemplation which has two aspects corresponding to understanding of the “emptiness of self” and that of the “emptiness of Dhammas”.

(3) The seventh consciousness defiles the first six consciousnesses with self and self-related afflictions. It is transformed into the Wisdom of Equality which understands the nature of the equality of self and of all other beings.

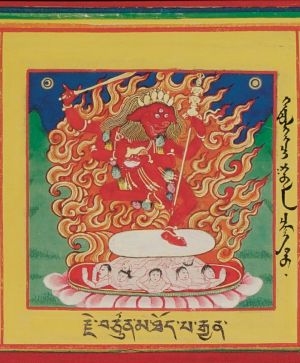

(4) The eighth, the storehouse consciousness, is transformed into the grand-mirror-like wisdom. This wisdom reflects the entire universe without distortion. Like mirror can reflect many objects simultaneously, the wisdom can perceive many objects accurately and simultaneously. This can be achieved by proper transformation of the Ālaya-vijñāna to this wisdom and is considered to be the state of the Buddhahood.

A similar principle is applied in the modern telescopes for observing the universe. The lens of a modern telescope is replaced by a mirror in order to avoid chromatic aberrations. Mirror of the telescope reflects the true image of the space and universe.

Conclusion

In Yogācāra concept, true knowledge begins when consciousness ends. Thus, “Enlightenment” is considered as the act of bringing the eight consciousnesses to an end and replacing them with enlightened cognitive abilities (jñāna). Here, the sixth consciousness (Manas) becomes the immediate cognition of equality (samatā-jñāna) by equalizing self and other. When the Warehouse Consciousness finally ceases it is replaced by the Great Mirror Cognition (Mahādarśa-jñāna) that sees and reflects things truly as they are (yathā-bhūtam).5,6,8

Thus, the grasper-grasped relationship ceases and the mind projects the things impartially without exclusion, prejudice, anticipation, attachment, or distortion. These "purified" cognitions remove the self-bias, prejudice and obstructions that had previously prevented a person from perceiving beyond his selfish consciousness. Since enlightened cognition is non-conceptual, its objects cannot be described. So, the Yogācāra School could not provide any description regarding the outcome of these types of enlightened cognitions except for referring these as 'pure' (of imaginative constructions).3,5,8

References

1. Keenan, J.P. 1988. Buddhist Yogācāra Philosophy as Ancilla Theologiae. Japanese Religions 15: 36.

2. Pensgard, D. 2006. Yogācāra Buddhism: A sympathetic description and suggestion for use in Western theology and philosophy of religion. JSRI 15:94-103.

3. Lusthaus, D. 2002. Buddhist Phenomenology: A Philosophical Investigation of Yogācāra Buddhism and the Ch’eng Wei-shih lun. New York: Routledge Curzon.

4. Suzuki, D.T. 1998. Studies in the Lankavatara Sutra. New Delhi: India Munshiram Manoharlal Pub Pvt Ltd.

5. Chatterjee, A.K. 1975. The Yogācāra Idealism. Varnasi, India: Bhargava Bhushan Press, the Banaras Hindu University Press.

6. Tripathi, C.L.1972. The Problem of Knowledge in Yogācāra Buddhism. Varnasi, India: Bharat-Bharati Press.

7. King, R.1994. Early Yogācāra and its relationship with the Madhyamika school. Philosophy East & West 44: 659.

8. King, R. 1998. Vijnaptimatrata and the Abhidhamma context of early Yogācāra. Asian Philosophy 8(1): 5.

9. Yin, J. 2009. Yogācāra school and Faxiang school. Hong Kong: The Centre of Buddhist Studies, the University of Hong Kong.