DHARMA LINEAGES IN THE PERIOD OF THE “LATER SPREAD”

by Michelle Janet Sorensen

Chos lugs, or Buddhist Dharma lineages, that have maintained a distinct identity in Tibet to the present were systematizers as well as nascent institution builders during period of the Later Spread. These so-called “New Schools”—the Sakyapa, Kagyupa, and the Kadampa as assimilated into the Gelukpa—developed tenet systems and doxographies, often organized around particular classical commentators such as Nagarjuna and Candrakirti and transmitted through orthodox

figures such as Atisa, Rin chen bzang po, Rnog Lo tsa ba and Pa tshab lo tsa ba. While these schools would become key political players in the cultural development of the Tibetan plateau, Dan Martin emphasizes that these three traditions were “arguably the three largest and most successful ‘lay initiated movements' of the times,” given that their key founders or transmitters were laypersons, as were their followers (1996a, 23-24).

The Nyingmapa lineage was also developing—as well as being given—a particular identity during the Later Spread. In order to assert the authority of the teachings and texts that the Nyingmapa considered foremost in importance, practitioners who maintained their commitment to and belief in early

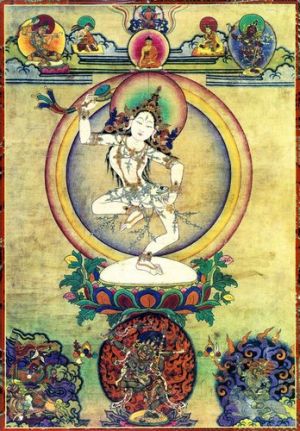

transmissions of Buddhism to Tibet also became more organized. However, given that Nyingmapa identity was constituted through reaction to the institutional and doxological activities of the New Schools, the forms of organization undertaken by the Nyingmapa would continue to reflect these differences. For example, many learned and experienced Nyingmapa practitioners remained lay people and/or itinerant yogins, in contrast with the emphasis on celibate monasticism in the organization of the New Schools.

Due to the emphasis on such activities as transmission, exegesis and systematization by these indigenous traditions of Tibet, Ruegg has characterized this period as one of “full assimilation” of the Buddhadharma (1979, 288). Yet it must be remembered that this was a dynamic time in the transmission and articulation of the Buddhadharma by the Tibetans and their foreign colleagues. The identities of “schools” and “lineages” were still very fluid in Tibet,

and individuals would study a variety of texts and practices with a variety of teachers from a variety of backgrounds. Machik Labdron received her early teachings from the Abhidharma scholar, Drapa Ngonshe, who eventually encouraged her to study with the accomplished Vajrayana master, Kyoton Sonam Lama. Karma Pakshi (1204-1283) was raised in a family of yoga practitioners before receiving Buddhist ordination and being recognized as the second Karmapa; he

then continued his training in a diverse array of teachings with a variety of teachers. Kapstein makes a similar point about the fluid relationships between schools and doctrinal approaches in his discussion of self-representation in the history of Tibetan Buddhism. He qualifies this point by stressing that the individuality of significant Tibetan thinkers must not be forgotten: “regardless of significant areas of overlap, there remain striking

differences of approach and content among them” (2000, 119). Martin remarks on the “strong sense of freshness and vibrancy, and often an urgency, in their discussions of religious issues” that characterizes the works of great teachers from these lineages from the mid-12th to mid-13th centuries (1996, 47). Martin also points out that “the sectarian identities that have since become so familiar to us were not yet foregone conclusions,” and thus the popularity

of “lay movements” and “accomplishment transmissions” must be fully considered in order to understand the complex Buddhist landscape during the era of the Later Spread (Martin 1996, 47). Moreover, sectarian identities did not prevent symbiotic relationships. Perhaps the most abiding symbiotic thread was between the Kagyu and Nyingma teachings, features of which are still referred to as “Ka-Nying.” These traditions have an affinity in their emphasis on experiential practice over scholastic doxographies.