Deities in Buddhism

Many Mahayana, and especially Vajrayana, Buddhists utilize images of bodhisattvas beings who aspire to relieve all suffering, forgoing their own enlightenment to do so] in the practice of Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism especially, is famous for the highly developed iconography used to express aspects of the Buddha dharma in the scroll paintings known as tangkas [sometimes spelled thangkas, etc.]. Cast metal images (Skt. rupa, form) are also used on personal shrines and in temples and teaching centres.

This article introduces some of these figures whose origins and qualities are often derived from Buddhist scripture, but also from legends told about the efficacy of their activities as a means and support for the enlightenment of all sentient beings.

The beings referred to as Buddhist deities perform different types of functions for the practitioner. They may be a focus or aid to individual meditation and transformation, in which case they are called yidams, or they may function as a protector of the dharma and/or of a class of being. In all cases, they function as a means to liberation and enlightenment.

For example, though a female deity such as Ushnishavijaya is known as a bestower of longevity, her purpose is not simply as a personal protector, but as a means to the liberation of numberless individuals via the extended life of just one.

Maitreyanath explained that

If the causes are fully ripened,

Buddhas will appear there and then

(Performing) wholesome activities.

In accordance with the disciples, the place and the time.

~ quoted by Geshe Palden Dakpo

Buddhas and bodhisattvas - those who in the process of becoming fully enlightened and who out of compassion, choose to stay and help those caught in the cycle of existence - are thought to be accessible to us in one way or another. We can know and identify them by way of the visions of advanced practitioners who have described them for us in a picture or in words so that we can relate to them.

Fully enlightened beings are thought of as having the capacity to exist in three levels of reality. The levels are often thought of as hierarchical, but whether one experiences a dharmakaya, nirmanakaya or samboghakaya form is generally considered to depend upon one's own capacities.

According to the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, Buddha Shakyamuni taught the tantric approach, or Vajrayana including the use of deity practices, in a fourth Turning of the Wheel. In particular, he transmitted the Kalachakra and/or Guhyasamaja tantras.

The Guhyasamaja (Tib. sangwa-dupa) which focuses on the [[primordial buddha] Akshobya]] is believed to be one of the first Sanskrit works to be translated into Tibetan. Holding a vajra, bell, wheel, jewel, lotus and sword, this deity symbolizes the essential unity of all buddhas.

Kaladarshan essay and image of Guhyasamaja (Secret Assembly)

15th-century tangka of the deity

Why call them deities; why not gods?

Although the word deity was originally a synonym for god, experience has shown that some practices such as those performed by Buddhists consist of a type of address in which the intent is rather different from the usual ancient one. That is, the general intention is not to flatter, placate or enter into contracts.

There is another important difference between Buddhist deities and mythological gods or goddesses. The latter are, or were once, considered real -- described as motivated by jealousy, power and other appetites and not very different from physical creatures such as people. The deities of Buddhism are ultimately regarded as manifestations of Emptiness. In fact for some practitioners, deity devotion is eventually abandoned as a technique or method for attaining an enlightened state when it has outlived its utility.

When deities are depicted in sexual union (called yab-yum or father-mother) this symbolizes intimate union of another type; that of skill and compassion, or Means and Method, or Wisdom and Emptiness.

Some well-known Buddhist deities are Amitabha (Opameh, in Tibetan), his emanation Chenrezi (Avalokiteshvara in Sanskrit), and Tara, the female bodhisattva who is called upon particularly in times of distress.

Kwan Yin (Gun Yom), beloved by Buddhists of east Asia, is a combination form with the qualities of Chenrezi and Tara. In Japanese, she/he is called Kannon or Shokanzeon Bosatsu (bosatsu = bodhisattva) and in Korean, Kwanseum Bosal or Kwan Um.

Rutgers University Associate Professor Yu Chun-fang has made his interesting article, Ambiguity of Avalokites'vara and Scriptural Sources for the Cult of Kuen-yin in China available on the Internet.

The Creation of Goddess of Mercy ...

The Kuan Yin depicted is known as The Water and Moon Kuan-Yin Bodhisattva. It is a Chinese figure of polychromed wood, 95" high from the Northern Sung (960-1127) or Liao (907-1125) dynasties. It is at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

Legendary figures

One category of venerated beings consists of the 16 arhats (Pali: arahant) or disciples of the historical Buddha. They are shravakas or 'hearers' believed to be among those present at the first Buddhist council. (The link is to line drawings and descriptions at Buddhanet.) In the Chinese tradition, they number 18 and are called the Lohan (Luohan>arahan>rahan>lahan) an expression that has also come to mean 'vegetarian' when it appears on a menu. In other languages they are also called Rakan.

Buddha Families

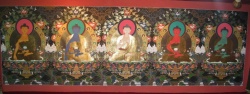

According to one scripture, Buddha Speaks of the Amitabha Sutra, Shariputra is told that there are innumerable Buddhas. [see the notes at the end for a list of Buddhas mentioned.] There is a convention, however, in which there are considered to be five transcendent Buddha Families. All the buddhas are manifestations of Emptiness, but they have distinctive samboghakaya forms.

Once referred to as the Dhyani Buddhas (Lama Angarika Govinda's Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism) each family has a chief figure who is associated with a cardinal direction (plus the zenith or Space) and is considered the head of a family. The families are: Tathagatha or Buddha family, Vajra, Lotus, Jewel, Karma.

Besides the symbol, eg. lotus, vajra, etc. each has a characteristic colour and a female consort also known as his "method" or actualizing manifestation. Each also has been seen as representing one of the "heaps" or skandhas, and each is also associated with one of the Realms in the Wheel of Rebirth. Each is believed to inhabit a Pure Land or "heaven."

They also embody aspects of Enlightenment. For example, Akshobya is considered Enlightened Mind, Vairochana is Enlightened Form and Amitabha Enlightened Speech. And the practice of each of the Buddhas is thought to act in such a way as to offset a negativity.

The historical Buddha is seen as only one manifestation in a chain or series, a nirmanakaya form of one or other of the transcendent Ones. Buddhists of the Kagyu denomination consider that the very dark blue Buddha of the Center or Space (or often, the East) Mikyopa or Akshobya (Unshakeable) in the form known as Vajradhara (also considered a form of Shakyamuni), is the source of enlightening method. His vehicle (associated animal or support) is the elephant and his attribute is the vajra. He is depicted touching the earth (Skt. bhumisparsha mudra) with his right hand in testimony to the power of merit in overcoming opposition. (This is a symbolic reference to Shakyamuni's encounter with Mara.) His consort is white Lochana lending continuity to the fact that while he fulfills the role of purifier and preceptor, he appears as princely white Vajrasattva holding a dorje and a silent bell. (Alternately, Vajradhara and Vajrasattva have also been described as forms of Vajrapani who is a bodhisattva of Amitabha's family.)

Aksobhya is associated with All-pervasive Consciousness of which deep space or the profound ocean is a symbol. The stain or obscuration (Tib. klesha) that he neutralizes is that of anger. Hum (Tib. Hung) is the seed syllable of his mantra.

Akshobya as depicted by Andy Weber.

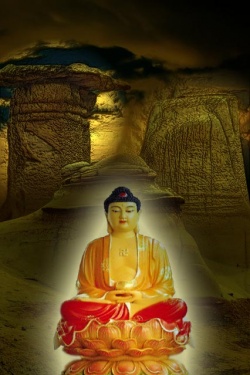

Amitabha ( Opameh) is the Buddha of Infinite Light, the one among the ultimate Buddhas thought to occupy the Western direction of space. He is associated with the element of fire and with overcoming the klesha of fear. Hrih is his seed syllable -- the one associated with the heart center.

The emblem of the red Buddha of the West is the lotus, and Amitabha with a benevolent smile sits in endless meditation (dhyana) holding a food bowl, under a tree by a lake, with peacocks supporting his throne. The bowl in his lap contains the ambrosia of eternal bliss.

In many cultures, but especially in Japan and China, he is thought of as the ruler of the Western Paradise where the virtuous will find themselves after death. This lush and be-jeweled land is illuminated as if by the setting sun so that everything is a golden-red.

In some depictions, he is shown making the abhaya mudra with his right palm facing us in the familiar 'stop' gesture which here may be interpreted, ‘stop being afraid’, that is, a gesture of protection. His left hand may be in the gesture of granting blessings or wishes. Sometimes he is depicted holding a red peony. Where ever people feel helpless in the face of life's circumstances, his cult is very popular.

In many parts of the world devotion to Amida, as he is known in Japanese, developed into a school of Buddhism in which it is considered unnecessary to do any other practice but repeat the mantra of Amitabha. Indeed, in some sects the mantra written in calligraphy, is itself, an object of worship.

The Western paradise of Amitabha is called sukha-vati in Sanskrit, or Blissful Land. However, in the conventional translation from Chinese and Japanese it is known as " Pure Land" despite the fact that there are many other such Lands, and so the form of Buddhism just described is known as Pure Land Buddhism.

Pure Land Buddhism centres on his practice or even merely the recitation of his mantra: OM Aami Dehwa Hri, but Sukhavati (Realm of Bliss) which is the name of his pure land, is mentioned by all Tibetan Buddhists in many different circumstances, most especially at the time of dying.

Other transitional events -- any beginnings or endings, if only of the Western somewhat arbitrary calendar system -- are often occasions for uneasiness. Thus, at the request of several communities around the world, the sadhana or ritual of worship chosen by Tibetan Buddhist centres for the time just before New Year's 2000 was the text called Maha Sukhavati that concerns Amitabha.

Read a description of this First Light Project and see images in the section called 'Gallery' of Densal On-line

Amitayus [Tib.: Tsepameh) is an expression of Amitabha. His distinguishing attribute is a flask of amrita which heals any illness and confers immortality.

Vairochana whose name means Radiant is the patron of the Gelugpas. As such, he will occupy a central position. Otherwise, like the rising sun that illuminates darkness, he is considered to occupy the East and his colour is white. He stands for wisdom in the form of understanding. His method overcomes ignorance or delusion. His vehicle is the lion, symbol of the royal lineage of Shakyamuni and the superiority of the Buddha dharma as a method. This is the Buddha as Teacher; he makes the turning wheel gesture (dharmachakra mudra) which evokes his sermons and his setting in motion the system compatible with the wheel of rebirth. Om is the syllable associated with him. He heads the Buddha family.

Ratnasambhava means Jewel-born. Associated with the South, he is golden

yellow, and earth is the related element. He is associated with the riches of the earth and the realm of earthly existence. His attribute is a Wish-fulfilling Jewel (Skt. chintamani) the stone of mythology that usually grants 3 wishes. Here it grants our "heart's desire" which is to be always happy; that is, to put an end to suffering by means of the Dharma. He heads the Gem family and his way of liberation is via sensation and emotion. He helps overcome craving and greed.

Ratnasambhava's throne is supported by horses. He makes the boon-bestowing gesture (varada mudra) with his right hand. The seed syllable of his mantra is Tram. Practices associated with him work to transmute the poison of pride.

Amoghasiddhi (Unerring Achiever) is called Donyo Drupa in Tibetan. He is dark green, and is associated with the North. His practices overcome envy and jealousy. He is associated with the air and with our attitudes of mind. His symbol is a cross formed by two vajras (Skt. vishvavajra) and his seat is supported by shang-shangs or "garudas". With his right hand he makes the gesture, "Do not fear (abhaya mudra") which is a sign of complete refuge or protection. His seed syllable or bija is Ah. He overcomes through introspection, meditation and the use of the breath.

See the 5 orders of Dakinis.

See the 8 Bodhisattvas.

The Refuge Tree

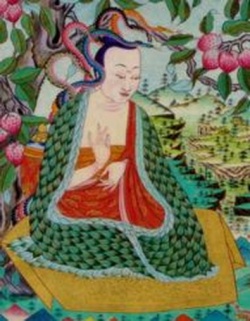

Each denomination, and even each lineage has a chart of the "geneology" of its founders and teachers known as the Refuge Tree. It is depicted as a wondrous tree with several branches. In the sky overhead with the sun and the moon is usually found the samboghakaya form of the founding buddha, and the bodhisattvas and dakinis associated with the lineage. On the upper branches are the founding human members and closer to the ground, we see the 20th-century masters. Living teachers are not depicted.

At the foot of the great tree, are the dharma protectors and the various kinds of offerings. At the bottom of the scroll or poster, are often representations of those who are taking refuge in the particular tree. Practitioners can imagine themselves there, and also, they can imagine a forest of similar trees belonging to the other lineages knowing that the Buddha, Shakyamuni appears above all of them.

A Nyingma Refuge Tree: incl. main deity-couple in their palace.

Other Nyingma Refuge Tree tangkas: Padmasambhava.org, [click on the small image for the enlargement.]

Yidams

In the Tibetan tradition, several types of figures are used as a focus for practice. Among them are found the so-called meditational deity or yidam, the lineage teacher or guru, the dharma protector who acts to overcome spiritual obstacles, and the dakini. All may serve as models of inspiration, as bestowers of grace or blessing, and as guides and protectors.

Yidams are sometimes referred to as tutelary deities. The "personal" deity or yidam is usually assigned by the spiritual mentor, guru or lama in accordance with the student's personality and life circumstance or karma. Sometimes it is said that the yidam chooses the student. The choice can be made in any of several ways. Through dedication to, and the ritual observance of a yidam, habitual tendencies and inclinations can be modified or overcome.

Wrathful Forms

People who are not accustomed to the 'language' of Tibetan Buddhist images are often surprised to see the wrathful deities for the first time. Perhaps, if you visited the link in the previous sentence, you are even pleasantly surprised.

One category is that of the herukas, a class of Vajrayana deities such as Chakrasamvara that is semi-wrathful with intimidating even terrible features. They are represented as partially nude with an upper garment of human skin and a tiger skin around their hips. They have a 5-skull headdress and carry bone rosaries, a staff or trident and a damaru (pellet drum) like the Hindu god, Shiva. Herukas are described in Tibetan books as beautiful, heroic, awe-inspiring, stern and majestic.

The eight Dharmapalas, Protectors of the teaching of the buddhas, have this appearance but in fact they are bodhisattvas - embodiments of compassion that can manifest out of Emptiness to act in an extremely wrathful way for the sake of sentient beings. [link is to Nitin's newsletter of Feb. 2001.]

Called in Tibetan, Drag-ched, the dharmapalas or defenders of Buddhism, are the 8 bodhisattvas: Mahakala, Yamantaka, Kubera, Hayagriva, Palden Lhamo, Changpa, Yama, and Begtse.

Tantric texts describe the very wrathful deities as terrifying. Stout with short but very strong limbs, many have several heads, hands and feet. Their complexions are likened to storm clouds, metals or precious stones, eg. black as the "cloud which appears at the end of a kalpa,” or “like a mountain of crystal” or like pure gold; of a red as "when the sun rises and its rays strike a huge mountain of coral.”

Their skin is oiled with sesame in the fashion of ancient times, or dusted like that of a sadhu with ashes from a funeral pyre; more horribly, it is covered with spots of blood and shiny specks of human fat.

They grimace fiercely with a maw from which protrude fangs of copper or iron. Often, in a profile view the upper teeth gnash the lower lip. A miasma of disease may issue from their mouths; a storm from flattened nostrils. They glower with three bulging, bloodshot eyes.

Mahakala (Great Dark One) is the name given to a number of the wrathful forms, mainly of Chenrezig. But not all wrathful forms of Chenrezig are Mahakala.

The details of Mahakala's form depend on the different lineages and situation contexts. There are several six-armed ones characteristic of the dharma protector, and there are also four-armed and two-armed ones. See a white or Sita Mahakala (Gonpo Karpo).

For example, as protectors of the different teaching lineages there are the two-armed, big-mouthed Mahakala Bernachen of the Karma Kagyu, four-armed Mahakala shown here who is protector of the Drikung Kagyu, and six-armed Mahakala of the Gelugpas.

Changpa Karpo (White Brahma) is the Buddhist view of Brahma. In this context, the usually 4-faced, 4-armed deity that in Indian mythology traverses space seated with Lakshmi his consort, on Garuda is here mounted on a white horse, brandishing a sword. He is a "defender of the faith" and does not usually have the fierce-some attributes of the others. His head-dress is topped by a conch shell jewel and over his robes he wears Mongolian armor.

Hindu mythology tells how Brahma had designs on his own daughter, though she managed always to place herself above his many heads so he could not get at her. The Tibetan account has a similar motif:

Changpa Karpo rode a wondrous horse that sailed the sky during the day, but at night descended to earth. Once, while in the heavens, he seduced a goddess named Dhersang, and stole a wish-fulfilling jewel. The guardians of heaven grabbed him by his tongue, flung him to the ground, and took back the jewel along with his very heart.

This naturally resulted in an increase in his viciousness -- he murdered men and raped women. He met his match in Ekajati, who when he tried to touch her, whipped him so hard on his thigh with her turquoise-bedecked silk undergarment that he became crippled.

This wound, similar to that received by Jacob in the Old Testament as he wrestled with an angel, transformed him into a protector or dharmapala.

Beg-tse (The Master of War) emerged as a dharmapala after the Mongols under Altan Khan took Refuge in 1577 via the teachings of the Third Dalai Lama.

Like Changpo Karpo, he is also depicted mounted and in armour. With his right hand he brandishes his scorpion-hilt sword, his left hand clutching his bow is raised to his mouth as he is about to eat the heart of an enemy.

Vajrabhairava seems to have derived from the fierce Indian god Shiva in his form of Bhairava (Terrifier); to Buddhists this dark bull-headed figure has become Yamantaka, Dorje Jigche (Jigji) the Death-Slayer who is a fierce form of the gentle Mañjusri, one of the Buddha's disciples. Fearsome in appearance they may be, but all of these deities are manifestations of compassion.

Some Nepalese Buddhist deities are particular to that culture. Mahasamber, 'The Great Defender' is a Nepali example of Yamantaka, the complex Buddhist guardian:

He has seventeen heads in five rows, four in each row and one at the top. The main head of the four in each row faces the front and is blue on the right and green on the left. The heads on the blue side are yellow and the pairs of heads on the green side are blue, green and red. The heads are larger at the bottom and smaller at the top. All the faces are demonic, ie square shaped with three bulging eyes, heavy eyebrows, gaping mouths and fangs. The colour division of the main faces is continued all the way down the body, the right half being blue, the left half green. he has two sets of 17 and 18 arms, ie making 70 arms. Each of Maha Sambara’s feet has six toes and he stands with legs astride in alidhasana.

There are also four main arms, besides the four in which he embraces his consort, Vajravarahi.

Kubera (Tib. Namtoseh) is also the Hindu god of wealth, and possesses the Jewel-spitting Mongoose. Kuvera in this context acts to serve and disseminate the Dharma. Sometimes Jambhuvala, King of the North, fulfills this enriching function.

Yama is the Hindu god of Death. He figures in scripture besides embodying an important aspect of Buddha-dharma.

Visit Making Offerings for an account of procedures concerning the practices of wrathful deities.

Sangye Menla is the blue Medicine Buddha who holds in his lap the lapis lazuli (dark blue semi-precious stone] bowl of amrita, the elixir of life in the form of an ambrosia which heals all illness. He is often depicted in the company of healing figures of other colours.

These are not images of Buddha (Shakyamuni), at all.

The fat body is, as we know, an indication of lots of food; therefore of blessings in the form of prosperity.

One statue found in Chinese and Vietnamese commercial establishments is Jambhuvala the guardian king of prosperity, Mi Fo. He may be seated on a sack of treasure holding in his left hand, a gold ingot shaped like a boat or hat. He is associated with the jewel-spitting mongoose often misunderstood as a mouse, rat, or a shrew. He may also be depicted with a fan or a walking stick, and a mala in his left hand.

In the Tibetan tradition, his counterpart is Namtoseh

Then there is a Chinese form some think is an aspect of Maitreya*, the future Buddha. [click for one person's experience with this kind of Thai or Chinese image].

Hotei is the chubby figure with children crawling upon him, and/or animals before him. He is called Huashang in Tibetan. He is the Chinese emissary sent to invite the Buddhist teachers to that land.

Scripture Deity

In Tibetan Buddhism, the sutra known as the Prajnaparamita (Perfection of Wisdom) was deified as an aspect of White Tara. This Tara is also related to the Indian Sarasvati who is the deity of letters, music and the other intellectual pursuits.

Similar to the devotion given Buddha Amitabha is the movement which originated in the teachings of Nichiren who lived in 13th century Japan. He promoted the idea that the text known as the Lotus Sutra was itself a sort of deity having soteriological [saviour-like] powers. This sect is quite popular today in the West.

Tina Turner, the successful singer, stated in her autobiography that she owes her success in overcoming a difficult series of life-situations to her daily repetition of the Lotus Sutra mantra: Om namo myoho rengeh kyo which combines Sanskrit and Japanese.

Buddhist teachers of all schools stress that all such deities are to be thought of as embodiments of wisdom and compassion, not separate from the practitioner or meditator, and ultimately empty of any inherent qualities.

Aspects of a Buddhist Deity

Any Buddhist deity may manifest in four ways: benign, active, semi-wrathful and wrathful. That is, their activity is pacifying, enriching, magnetizing, or subduing/destroying. The four-armed form of the protector, Mahakala, seen above, demonstrates by means of his gestures or mudras, all 4.

An example of a wrathful deity is Guru Drakpur. This is a manifestation of Amitabha's activity via Padmasambhava as Vajrakilaya, vanquisher of malevolent obstructions [lit.>Sanskrit: indomitable sin-eliminator].

Originations:

There may be some variety in the description of a deity in the Vajrayana or tantric Buddhist tradition. One reason for this is that sadhanas, or ritual practices of a deity may have appeared, been revealed, uncovered or discovered, via different teachers in different places and times.

It was often the case that a practice had a long tradition in South India where the fame of its efficacy and of its masters drew Tibetan teachers/translators to undertake the arduous journey to fetch it for the benefit of beings of northern Buddhist lands.

However, sometimes circumstances did not permit its wide dissemination, and it was then concealed or secreted for use at a later time. Re-discoverers are known as tertons, and revealed tantras are called termas.

Especially effective or popular sadhanas can exist in a multiplicity of forms as a result of the denomination and/or the distinctive teaching lineage of practitioners.

Vajrakilaya (also, Benzarkila or Vajrakila. Tibetan: Dorje Purba) is a winged dark blue wrathful deity or heruka whose characteristic implement is the purba (phurba,] the 3-sided 'spirit nail.' He is said to have appeared as an aspect of Padmasambhava to subdue the opposing and chaotic forces which tried to prevent all activities motivated by compassion and generosity from penetrating Tibetan culture. [Link is to Tibet Art image of Nyingma/Sakya lineage tangka.]

When Vajrakilaya works through the activity of the purifier, Vajrasattva, he is called Vajrakumara (Tib. Dorje Shönnu), or Indomitable Prince.

Vajrakilaya is also considered the wrathful embodiment of bodhisattva, Vajrapani, as he acts to subdue, purify and transform the actions of those whether gods, rakshas or people, who seek accomplishment or power for selfish or irresponsible reasons.

Indian Gods and Goddesses

There are a number of gods and goddesses from the Hindu tradition who appear in the Buddhist context. The four high gods: Brahma, Indra, Shiva and Vishnu and their respective Shaktis are integrated into Buddhism.

Not all the gods of Hinduism are considered 'deities', but one of those that is is Ganesh, the elephant-headed son of Shiva who overcomes obstacles. When Ganapati or Ganesh is considered a means to obstacles, he can be depicted as being trampled underfoot.