Dzogchen Meditation

- The practice of Dzogchen Meditation is centered around the recognition of Natural Awareness.

Natural Awareness refers to the true nature of our mind when it is free from habituation. Ordinarily in our day to day lives our minds are continually involved in habitual thought and projection.

This habitual thought and projection is what obscures Natural Awareness.

Therefore we can understand Dzogchen Meditation as a practice which purifies the mind of habituation thus allowing us to recognize Natural Awareness.

Since our habitual mind depends on constant movement, distraction and manipulation of what arises in experience, the fundamental form of practice in Dzogchen is to sit still and be undistracted; to leave whatever arises in our field of awareness as it is, that is, not to manipulate or strategize our thoughts or the sounds and sensations that we feel. This is called the “resting meditation of a kusulu.”

“Keep your body straight, refrain from talking, open your mouth slightly, and let the breath flow naturally. Don’t pursue the past and don’t invite the future. Simply rest naturally in the naked ordinary mind of the immediate present without trying to correct it or replace it.

If you rest like that, your mind-essence will be clear and expansive, vivid and naked,without any concerns about thought or recollection, joy or pain. That is awareness (Rigpa).” Khenpo Gangshar

To practice Dzogchen meditation, sit on a cushion or chair in the meditation posture.

The spine is straight, not leaning to the right or left, front or back, comfortable and relaxed but upright, alert and awake.

The eyes are open either looking straight ahead or slightly downward about six feet in front not looking around or staring intently at anything.

The mouth is open slightly and the breath naturally goes in and out.

The basic idea here is that what we do with our body affects our mind.

This posture helps our mind to recognize and ‘let be’ in the present moment which is essentially the complete practice.

There is nothing else that we are doing.

Minding the Gap: Knowing the Crucial Point of Recognizing Natural Awareness

“When your past thought has ceased and your future thought has not yet arisen and you are free from conceptual reckoning in the present moment, then your genuine and natural awareness, the union of being empty and cognizant, dawns as the state of mind, which is like space — that itself is dzogchen transcending concepts, the cutting through of primordial purity, the open and naked exhaustion of phenomena.

This is exactly what you should recognize. To sustain the practice means simply to rest in naturalness after recognizing.” Shechen Gyaltsab, Pema Namgyal

One traditional practice instruction states that when our habitual involvement in one thought has ended and we have yet to become engaged in the next thought we have the opportunity if we are attentive to recognize uncontrived natural awareness.

This is a very simple instruction and yet it is the key point of practice. Without knowing this key point all of our efforts in practice will essentially be worthless.

So what is it saying? How does this moment feel experientially? When we are doing our practice there are moments of simple awareness and there are periods of time when we are distracted and essentially caught in a daydream.

Ordinarily in our day to day existence we go from one daydream to the next with very little awareness.

they are big daydreams with lots of emotion and discursive storyline and sometimes they are very subtle daydreams.

But the main element of the daydream or delusion is that we are completely unaware of where we are and what we are doing in reality. We lose that basic awareness.

The daydreams however are not permanent and they naturally degrade and fall apart — at some point we fall off the edge of the daydream and momentarily touch the ground of awakened mind — Natural Awareness.

This is a naturally occuring phenomena.

When we sit and practice with unbiased awareness we become aware of these gaps between the distraction of daydreams. That is the gap we are recognizing again and again in our practice. .

As Dudjom Rinpoche writes, we simply gain confidence that thoughts and distraction are “self-liberated”: “Just as waves on the ocean subside again into the ocean, gain confidence in the liberation of all thoughts, whatever may arise. Confidence is beyond the object of meditation and the act of meditating.

It is free from the conceptual mind that fixates on meditation.”

The practice is simply to recognize the gaps in discursive thinking and to come back again and again to a basic awareness of being.

There is no need to apply some kind of conceptual meditation technique but rather we ‘let be’ in awareness that is undistracted by the usual habitual picking and choosing– accepting and rejecting– of what arises.

As Tsele Natsok Rangdrol writes: “When it happens that you do get involved in thoughts that recollect the past or entertain the future, then let be directly in awareness.

If a thought pattern continues, there is no need for a separate antidote since whatever takes place is liberated by itself.”

The point Tsele Natsok Rangdrol is making is that we do not need nor should we attempt to apply an antidote when we are caught in habitual thought.

The habitual thought will actually fall apart on its own. We simply have to pay attention with an unbiased awareness.

Any attempt to apply an antidote at this point carries with it a huge kind of hangover because we are trying to ‘fix’ our meditation state which is really just another habitual, discursive thought.

The profound fact of kusulu meditation is that we are sitting there doing nothing and occasionally, if we pay attention, we realize that we are sitting there doing nothing!

In the beginning of our practice it is useful to use a form of meditation taught by Trungpa Rinpoche which helps us to remain present and not space out.

First we place our awareness on the outbreath.

The outbreath becomes a very light-handed reference point for our basic awareness.

We go out with the outbreath and dissolve. Then the inbreath happens naturally. We don’t place any particular emphasis on it.

Then we go out with the outbreath and place our attention on the breath going out and dissolving. At some point a thought will come up and before we know it our awareness is captured in a daydream of discursive habitual thought.

When we realize this we label this daydream ‘thinking’ and return to placing our attention on the outbreath, and dissolving. Labeling the discursive story ‘thinking’ gives us a bit more leverage over it and allows us to come back to the awareness of the outbreath.

This technique allows us to clearly differentiate between being aware of our outbreath and being caught in ‘thinking.’

There are other profoundly helpful elements to this technique that should be noted. First, placing an emphasis on the outbreath as the main technique or main focus of awareness allows us to develop the constancy of mindfulness.

There is an automatic sense of feedback. If we are not aware of the outbreath then we have probably spaced out. Spacing out or not being aware of what we are doing is fundamental ignorance — the root problem with which we are working in meditation.

So being aware of the outbreath gives us a constant technique to sharpen our awareness.

By not continuing this state of mindful attention, by breaking it with the inbreath and allowing a gap in that ‘fabricated’ technique, we allow a natural awareness to develop and this is really the remarkable element of this practice because that built-in gap destroys our tendency to turn our meditation practice into a way of repressing ‘thinking’.

“Cast away the fixation of rigidly meditating upon a reference point and instead release your awareness into carefree openness!” Tsele Natsok Rangdrol

Both foundational Schools of Buddhism like the Shravakas and Pratyekabuddhas and non-Buddhist schools of meditation use concentration techniques in an effort to calm the mind.

In Buddhism this practice is known as shamatha and it is seen as a limited practice in the sense that it can create many more obstacles to realization than it solves.

On the plus side, the practice of one-pointed shamatha allows us to slow down the speed of discursive thought and by accomplishing this the practitioner can experience uncontrived awareness if they have had the “pointing out instructions” from a qualified master and know what to look for.

On the negative side shamatha practitioners can become attached to the ‘stillness’ of nonthought and mistake that for realization.

They may also cling to the experiences found in the cessation of discursive mind brought about by stopping thought through the application of concentration techniques.

By using one-pointed concentration to squash the arising of ‘thinking’ all kinds of peaceful and blissful states arise. Because they are pleasurable on a very refined level shamatha practitioners often cling to these experiences.

The habitual attachment and clinging to these meditation experiences keeps shamatha practitioners trapped in samsara.

In other words, shamatha meditation can stop disturbing emotions and thoughts and we can experience a blissful peace based on an absorption in a type of concentrated trance. The habitual patterns have not been undone, they have simply been interrupted by the mind’s preoccupation with something else — in this case the concentration technique itself.

As soon as we stop concentrating on the object of meditation we immediately resume our habitual patterns of thought and our disturbing emotions engage us in another samsaric daydream.

In contrast to this, in Dzogchen and Mahamudra meditation we use technique only to establish an unbiased reference point for awareness.

Because the technique is to be aware of the breath we can actually notice that we are daydreaming, label it ‘thinking’ and come back.

At the point of noticing we have actually already come back to an unfabricated, undistracted awareness.

What we are training in is the recognition of that moment.

There really is nothing more to do when we come back to that simple awareness — in fact if we attempt to force ourselves to stay present we taint that uncontrived awareness.

The most difficult aspect of our practice is learning to “let be” once the daydream falls apart because there is a tremendous habitual urge to jump on to the next thought.

It is only through doing this again and again that we wear out this tendency to jump.

Many teachers recommend “short moments many times”. but this type of instruction only works when you are in a longterm retreat structure.

If we just practice for short periods between checking our Iphone or facebook page we never wear out our habitual patterns.

So we recommend “short moments many times for a long time”. Just sit there and wear out the boredom and frustration, the fascination and exhilaration.

We only gain confidence in our Natural Awareness through watching every reaction arise, dwell and dissipate over and over again.

Eventually we become quite ‘shinjanged” — which is a tibetan meditation term for completely processed out.

Our shocking thoughts no longer shock us. We see them just as thoughts.

We can see everything that arises in our mind and we no longer react habitually as though the thoughts were real.

There is no substitute for sitting for long periods of time — none.

That is why we offer 10 day Dzogchen Meditation retreats here at the Center four times a year.

There really is no other way to directly penetrate the profound teachings of Trungpa Rinpoche’s practice lineage.

Gradually through doing this practice we begin to recognize a quality to awareness that permeates all of our experience.

What begins to bleed through is what is called “‘vipashyana”– or “clear seeing.”

We begin to perceive thoughts, feelings, emotions and objects beyond the obscuration of our habitual patterns of thought.

What begins as a gap between discursive, habitual daydreams expands and undermines all of our delusive patterns.

What we first notice only by experiencing the boundary between periods of daydreaming and Awareness begins to expand.

Trungpa Rinpoche used the analogy of the vast ocean of Natural Awareness undermining the mainland of habitual mind until it collapses into the ocean.

In other words — the boundaries are undermined by Awareness until there are no boundaries — just Natural Awareness.

“There is a children’s story about the sky falling, but we do not actually believe that such a thing could happen.

The sky turns into a blue pancake and drops on our head — nobody believes that. But in maha ati experience, it actually does happen.

There is a new dimension of shock, and new dimension of logic … Our perspective becomes completely different.” Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche

Awakening from the Daydream

“When you rest nakedly and naturally in the great openness of this awareness, do not be concerned with your old archenemy, the thinking that reflects, has myriad attribrutes, and has never given you a moment’s rest in the past.

Instead, in the space of awareness, which is like a cloudless sky, the movement of thoughts has vanished, disappeared collapsed.

All the power of [habitual] thinking is lost to awareness.

This awareness is your intrinsic dharmakaya wisdom, naked and fresh!” Dudjom Rinpoche

Even though the basis of our experience has always been the primordial perfection of Natural Awareness, up until we engage in Dzogchen practice we have been living in a habitual daydream.

Everything that arises in our field of awareness is conditioned by a habitual discursive dream state that we believe is reality.

We take our projected habitual thoughts to be our reference points — the story we tell ourselves of what happened yesterday and the story we tell ourselves of what we will do tomorrow, of who we love and who we hate — all sorts of scenarios and schemes that are just habitual discursive thoughts.

In our confused state we take these habitual reference points as solid and real, but of course, they aren’t solid and they are not real.

They are just thoughts and just discursive thinking.

They have no solidity and no reality outside our discursive, habitual mind.

What happens when we begin to dissolve this fiction through meditation practice? First of all, the world comes alive.

Every moment of experience is fresh, completely open and we are fully present in that moment.

All experience, while unique in itself, has the same taste of vividness and presence.

When the solidity of our habitual reference points dissolves the entire samsaric structure is shaken to its foundation.

At the same time the openness and clarity of experience without the cocoon of habitual reference point initially can be a rather frightening experience.

For countless lifetimes we have obscured this fresh present wakefulness with our habitual discursive thought and projection.

When we cut through and actually experience this fresh vividness it can be a freaky experience.

We quickly want to run back to our familiar habitual world. We become very aware of impermanence and of loneliness.

Fear begins to arise along with a feeling of immense space.

The habitual reference points have begun to fall apart and awareness has expanded.

As Dilgo Khyentse points out, the barrier that comes up at this point is a reaction to that larger awareness of space and energy — the habitual reaction to this feeling of groundlessness, of no reference point — is generally fear.

The way we work with this fear and groundlessness is to let be and open out into it without attempting to change it or manipulate it.

We lean into the direct experience and continue to open and cut through any habituation or defense mechanisms with greater openness and awareness:

“Clarity of awareness may in its initial stages be unpleasant or fear-inspiring; if so, then one should open oneself completely to the pain or the fear and welcome it.

In this way the barriers created by one’s own habitual emotional reactions and prejudices are broken down.

When performing the meditation practice one should develop the feeling of opening oneself out completely to the whole universe with absolute simplicity and nakedness of mind, ridding oneself of all protecting barriers.” Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche

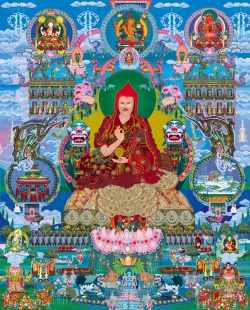

Beyond Meeting and Parting: Meeting the Guru’s Mind

“Awareness is first pointed out by your master.

Thereby, you recognize your natural face, by yourself, and are introduced to your own nature.

All the phenomena of samsara and nirvana, however they may appear, are none other than the expression of awareness itself.

Thus, decide on one thing — awareness!” Dudjom Rinpoche

There are many ways to receive the ‘pointing out instruction’ of Natural Awareness in the Tantric tradition.

But it is very important to realize that we must rely on an authentic lineage and the blessings of a realized Master.

“Receiving the Blessings” means that when we are in the presence of someone who has completely removed the obscuration of habitual reference point we can recognize a particular quality to our experience.

What we experience in their presence may not coincide with our conceptual idea of what “Awakened Mind” should feel like.

In fact, quite often our neurosis can be heightened or we may feel completely freaked out for no apparent reason.

Many times we feel very exposed and naked.

We feel it and we come to recognize the feeling through repeated encounters with the guru’s mind.

Later on in our own practice or just walking down the street we can recognize that again and again.

What we begin to realize is that our heightened neurotic response generally is our habitual mind attempting to cover over the gap or the naked awareness of the unhabituated mind of the guru.

At the point of encountering this naked mind we might be tempted to run for cover — and quite often we do — but some part of us recognizes the Awakened Mind in that experience as our true Natural Awareness.

In the Tantric Tradition we bind ourselves to that naked mind through yidam practice and guru yoga.

The meaning of the samaya vow is that having recognized the nature of the Guru’s mind as our Awakened Nature we commit ourselves to never turning away. We bind ourselves completely to the Awakened Nature of the Guru and the Lineage he represents.

This is what it means to depend on and have devotion for a realized master.

There are ,of course, many people who are buried under layers of habituation who will not experience the Guru’s mind or not recognize it when it is right in front of them.

In the beginning of practice it is necessary to have faith — just do your practice and clear away these habitual obscurations.

Its very helpful even in our cynical age to trust the words of our lineage Gurus! Some people in this life will never realize the nature of the Guru’s mind but will mistake it for something else. This boils down to ‘precious human birth.”

Believe it or not, the crazy people who recognize this mind are the lucky ones! Working on faith and devotion is of the utmost importance on the path of Dzogchen and Mahamudra.

“In order to truly recognize your nature, you must receive the blessings of a guru who has the lineage. This transmission depends upon the disciple’s devotion.

It is not given just because you have a close relationship.

It is therefore vital never to separate yourself from the devotion of seeing your guru as the dharmakaya buddha.” Shechen Gyaltsab, Pema Namgyal

Depending upon the openness and receptivity of the student, the genuine “pointing out instruction” can be through words, through the symbolic transmission of Tantric initiation, or through direct mind-to-mind transmission.

Actually, we say that transmission can occur through these three means but really all transmission is “mind to mind.”