Frequently Asked Questions about Buddhism by Lama Jampa Thaye

by Lama Jampa Thaye

The following text is extracted from Lama Jampa Thaye’s book, The Way of Tibetan Buddhism (Thorsons, 2001).

What is enlightenment?

How long does it take to become enlightened?

Does Tibetan Buddhism have any connection with the New Age movement?

How can we choose a book about meditation?

When we take refuge in the Three Jewels, does it mean that we take refuge in all Buddhist traditions?

Nowadays some people regard themselves as Buddhist but at the same time think that it is good to practise Christianity or another religion at the same time. Is this possible?

If dzok chen and mahamudra are the highest teachings, allowing one to attain liberation immediately, why do we need to practise a graduated path?

The vajrayana method involves meditation on oneself as a buddha deity. How does this practice work exactly? It seems somewhat unnatural to pretend that you are something other than yourself, like a god with four arms, for instance.

In dharma it is said we must develop love and compassion. How then can you explain the presence of wrathful deities and destructive rituals in vajrayana? Is it not unkind to harm a sentient being?

How do we choose a yidam?

Is there a rule that men practise male yidams and women practise female?

How can it be compassionate if we just sit on our meditation cushions without doing anything? How does this help other beings?

There are many rituals in vajrayana such as prostrations, circumambulations and so on. Are they not somehow too Tibetan for us Western people?

Why, in some Buddhist centres in the West, including yours, do people recite their prayers in Tibetan and not English?

With which lamas do we have samaya?

If one has received many initiations, is it necessary to practise the sadhanas of all of them?

If you have taken initiations and vows with a teacher who you later discover was not qualified, are you still bound to the commitments you have made?

Some people take initiations without actually knowing what they have got involved in. Does this make the samaya less serious?

When we read the biographies of Indian and Tibetan teachers from the past, sometimes these sound rather unrealistic. How much is true and how much has been added by their students as an act of respect?

Can meditation help people to stop taking drugs?

Are the experiences of taking drugs the same as the experiences of meditation?

There are many books about tantric sex. Could you explain more about this?

The Tibetan Book of the Dead is very popular in the West nowadays. Do you think that Westerners who are not Buddhist should read it?

Who are the revealers of the treasure-teachings and how do we know if they are genuine?

1. What is enlightenment?

One way to answer this question is to look at the etymology of the Tibetan term for ‘Buddha’. When the Tibetans came to translate Buddhist scriptures from the original Sanskrit, they focused very closely on the meaning behind the terminology rather than the literal value of the words. This includes the word for Buddha itself, the title of our teacher. In Sanskrit, Buddha means the ‘Awakened One’, indicating he has awakened to the true nature of reality.

The Tibetans translated ‘buddha’ as ‘sang-gye’, which is formed through the conjunction of two terms. The first, ‘sang’, means ‘to have purified or removed’. This indicates that a buddha has purified or removed all the elements that cover the true nature of one’s mind, that is to say the age-old habits of ignorance, desire, hatred and other mental poisons. A buddha is therefore someone who has freed himself or herself from the constraints and blindness of those states of mind. The second part of the word, ‘gye’, has the sense of ‘expanding’. Once one has cleared away the obscurations or veils covering one’s own true nature, the innate qualities of wisdom and compassion blossom and expand. Enlightenment is, therefore, to be partly understood in a negative sense as the clearing away of all that is foreign to our fundamental qualities, or buddha nature, but it is also the revelation of the intrinsically positive qualities of wisdom, compassion and power through which we can work endlessly for all beings. To become enlightened, then, means firstly to free ourselves from the hindrances of an egotistical view of the world and secondly, having freed ourselves, to engage in the world for the benefit of all beings.

2. How long does it take to become enlightened?

There is no set time. The qualities of wisdom and compassion that we uncover on the path exist within all of us right now. One can even say they are our primordial nature. What we are trying to do on the path is to free ourselves from identifying with that which is false, such as the notion that our body is our self, or that our distorted thoughts and emotions are our self. How long that will take us depends upon how much effort we put into following the spiritual path, but enlightenment is in a sense available to us right now. Of course, one needs to find an effective method for removing the obscurations. Having found the skilful teachers who can impart these to us, we then need to be fully committed to using them. It is said that there are beings, like the dzok chen master Garab Dorje, for whom enlightenment follows instantaneously upon their hearing one line of the teaching. However, such beings are as rare as stars seen in the daytime. The vast majority of us need to follow a graduated and systematic path. However, if we follow the most powerful of Buddha’s teachings, the vajrayana, then it is possible to become enlightened in this very life. Even if that is not possible, by sincerely setting out on the spiritual path in this life we should be confident that in successive lives we will carry on with this upward movement towards enlightenment.

3. Does Tibetan Buddhism have any connection with the New Age movement?

I recognize that there are many sincere people involved in what are nowadays called ‘New Age’ movements. From a Buddhist point of view, however, it is definitely unhelpful to construct a school or movement that cannibalizes elements of different and even contradictory religions or teachings, attempting to create some kind of synthesis from them. We need to be discriminatory in our spiritual endeavours.

We need to be clear-headed and informed about the real nature of the Buddhist tradition. This only comes about through study and contemplation over a long period of time. Study begins for most people with the reading of introductory books on Buddhism available in bookshops and libraries. Yet, in doing so, we must exercise care to ensure that those books are actually written by representatives of authentic traditions of Buddhism, because nobody else has the authority, or indeed the ability, to convey Buddha’s teachings. When we move beyond that initial period of reading and reflection, we can enter into an apprenticeship with authentic masters of these traditions. This is how we ensure that we will receive only teachings that have come from immaculate sources.

One quite common way of distinguishing between Buddhism and New Age movements is to examine the nature of the teachings. The Buddha’s teachings are very often radical and challenging to our sense of ego, to our prejudices and even to our preconceptions and assumptions about what a spiritual tradition should be. They are directed at the elimination of all self-centredness. It is sadly all too often the case that much New Age spirituality is in fact dedicated to the exact opposite, the reinforcement of the obsession with self, which according to Buddha is the root of all our suffering. So it is here that we can often see the clearest evidence of the distinction between Buddhist and New Age teachings.

Another diversion from Buddhism is seen in the way that many people who are interested in spirituality, and thus attracted to New Age movements, unthinkingly accept most contemporary Western values as being in harmony with spirituality. Yet, much of Buddha’s teaching, particularly his ethical teaching, is in direct contradiction to modern Western values. The challenge that the traditional teaching poses to modern moral assumptions on matters such as abortion should alert us to the distinctiveness of Buddhism. When a movement, however much it attempts to pass itself off as incorporating Buddhist values, is totally consistent with modern liberal humanist assumptions, then it is more likely than not to be New Age and nothing to do with traditional Buddhism.

4. How can we choose a book about meditation?

Actually, in a way you cannot choose a book in the hope of learning everything about meditation, because it is said in the Buddhist tradition that for such things we need the guidance of teachers, those who have already gone down the spiritual path. They are learned in the variety of teachings and will, even more importantly, have some experiences of the territory that we must pass through on the spiritual path. In particular, they will understand how to deal with the different types of meditation experiences that occur and the different types of pitfalls and problems that crop up. These are things we simply cannot learn from a book.

If somebody were looking for a book on meditation and he or she knew that they were not interested in Buddhism, then it should be said that this book or any other on Buddhism is not appropriate for them. Buddhism is a spiritual system that has the all-encompassing aim of discovering our true nature and awakening the qualities of wisdom and compassion to benefit all sentient beings. By contrast, many people who are interested in meditation nowadays are interested solely in gaining relief from stress and other contemporary problems. There is nothing wrong with such aims of course but they are not comparable to the far more profound and vast aims of Buddhism.

If somebody were looking for a book on Buddhism, I would advise that they start with something very simple such as the basic teachings on how we can choose between skilful forms of action that lead to happiness and unskilful forms of action that lead to suffering. We need books that explain those points so that, even before meeting any teachers, we feel that we can make a difference to our lives by following Buddha’s very simple and helpful advice. Once we have read about those teachings and seen their usefulness in bringing about a more relaxed and kind approach to people and things in our life, we will have the confidence to go deeper into the teachings. Start with something very simple, taken from any one of the Buddhist traditions, whether Theravada, Chinese, Japanese or Tibetan Buddhism; it does not really matter which one. Then you will at least know that it has not been mixed up with all kinds of unexamined Western assumptions.

5. When we take refuge in the Three Jewels, does it mean that we take refuge in all Buddhist traditions?

Yes it does, because no matter how we divide the different teachings of Buddhism, whether in terms of their nature: hinayana or mahayana; or in terms of their origin: Southeast Asian, Tibetan, Chinese, or Japanese; all forms of Buddhism start from a common root, which is the teaching given by Buddha himself. No matter what kind of Buddhism we follow, the three basic principles in which we must place our trust and confidence are the Three Jewels. As explained earlier, these are the Buddha, the great teacher who showed us the way to liberation, the dharma, the teachings he gave us explaining how we can follow the path to freedom, and the sangha, the men and women who have gone before us on the spiritual path and can help us with the practice of the dharma. When you take refuge and thereby formally become a Buddhist, you are not enclosing yourself within a single tradition. Taking refuge in the Three Jewels makes you a follower of Buddha himself. That is a really important point and one that we need to understand in order that we do not fall into the narrowness of assuming that one particular Buddhist tradition is better than the rest. All the Buddhist traditions that exist in the world have come from Buddha’s original teachings and all are equally valuable. Even though it is necessary to study and practise one tradition primarily, the very fact that the act of taking refuge is common to all of these different traditions means that one should nonetheless feel part of the greater sangha, the sangha of all Buddhists. This will give our practice the necessary width and openness that are so essential for true spiritual growth, which is never anything to do with partiality, bigotry or feelings of superiority.

6. Nowadays some people regard themselves as Buddhist but at the same time think that it is good to practice Christianity or another religion at the same time. Is this possible?

I am afraid that when people attempt to do this, they are actually ignoring a very basic Buddhist teaching. There are three different trainings we should follow in order to maintain and strengthen the sense of connection we develop with the Three Jewels in taking refuge. Having taken refuge in the Buddha, we should not take refuge in other teachers or gods. The reason for this is that taking refuge in the Buddha means to see him as the supremely skilful teacher, the one who has clearly discriminated the true nature of phenomena and the one who is able to lead us out of the cycle of suffering. Relating to the Buddha in this way implies that we regard his wisdom as unequalled by other religious teachers and figures. We cannot honestly say we are following Buddha, with his particular explanation of the nature of the universe, and simultaneously follow a teacher who has, for instance, a theistic vision of the universe, a view contradictory to the Buddha’s non-theistic vision. By attempting to follow two ultimately contradictory systems, we will be split in half.

Having said that, there is of course much to admire in non-Buddhist religious systems. For instance, in some of the moral teachings and social services of modern religions we find a great deal of virtuous behaviour. We should appreciate those characteristics and praise them. When we have made the decision, based upon intelligent understanding of Buddha’s teachings, to practise Buddhism, we cannot then contradict the fundamental teachings by attempting to rely upon other religious systems. In this way, we uphold the distinctiveness of Buddhism, the very thing that attracted us to it in the first place, but we also show kindness and tolerance to the followers of other religious traditions.

7. If dzok chen and mahamudra are the highest teachings, allowing one to attain liberation immediately, why do we need to practice a graduated path?

Although a beginner can obtain a glimpse of the true nature of mind when he hears such teachings as dzok chen and mahamudra, it is an unfortunate fact that habitual distorted perception quickly causes the re-emergence of desire, hatred and ignorance. Such habits are so strong that even if we have some glimpse into our true nature, they quickly reassert themselves and cover over that glimpse. This means that the vast majority of us need a way of subduing these habits which obscure the true nature of mind. The initial way of dealing with them is to rely on such teachings as the ‘Four Thoughts that turn the mind to dharma’, generating bodhichitta and other methods of the hinayana and mahayana. A more powerful way of working with them, however, is to use the vajrayana methods. The obscuring habits themselves are frozen mental energy and vajrayana meditations of the development and fulfilment stages melt that frozen mental energy. When this energy is unlocked in this way, it is found to be nothing other than the buddha nature mind itself.

At this point one might ask if one could not simply practise the vajrayana and forego the more fundamental practices mentioned above? Unfortunately, I am afraid that for most people it is too difficult to use the vajrayana without first going through the basic teachings. Fundamental teachings such as the Four Thoughts are easily applicable to our present human situation. They allow us to develop a sane and steady approach to the spiritual path that will serve us well when we enter into the intensely powerful vajrayana. Without that sane and steady basis, we are likely to be swept off our feet by the deeper teachings. They are extremely powerful and their power may be misapplied and actually harm us. That is why in all the traditions: Kagyu, Sakya, Nyingma and Gelug, one begins with the Four Thoughts as the foundation for the tantric path.

8. The vajrayana method involves meditation on oneself as a buddha deity. How does this practice work exactly? It seems somewhat unnatural to pretend that you are something other than yourself, like a god with four arms, for instance.

Of course it is deeply unnatural to pretend that you are something you are not. In fact, one could say that this is the main cause of our problems. From time without beginning, we have been pretending that we are unchanging and immutable when we are not. At various times we imagine our self is our body, emotions or intellect, and that very delusion is what has landed us in the terrible mess we now experience. If that were what vajrayana was prescribing, it would not be an effective remedy to our problems in the slightest. So we should be clear about this. When the four classes of tantra in the vajrayana refer to deities upon which we meditate, they are not talking about external beings, like the kind familiar to us from theistic traditions. Nor are they talking about new personalities that we might somehow create within our mind. The deities are actually the embodiments of the primordially existent qualities that are already present within our awareness. Our awareness, in its true nature, is absolutely boundless, clear and compassionate. The deities themselves are to be understood as the manifestation of those intrinsic qualities. So when we meditate on our identity with those deities, we are actually unlocking and identifying with the deepest qualities of our fundamental nature.

9. In dharma it is said we must develop love and compassion. How then can you explain the presence of wrathful deities and destructive rituals in vajrayana? Is it not unkind to harm a sentient being?

We cannot imagine that Buddha would teach methods that would bring about suffering. Let us clarify, therefore, what we mean when we talk about wrathful deities. As I have already said, the deities taught in the four classes of tantra are neither external beings nor independent personalities. They are just the embodiment of our primordially enlightened nature whether they are in peaceful or wrathful form.

With regard to the so-called ‘destructive’ rituals which rely on either wrathful yidams or on the invocation of the ‘dharma protectors’, such as Mahakala and Mahakali, what is being represented here is a particular type of compassionate means for benefiting others. It is a fact that although most of the time we can benefit and give help to others through very gentle methods, sometimes we have to be more forceful. Just as in order to protect our children from harm we have to sometimes intervene vigorously, perhaps warning them with loud voices of some imminent danger, or snatching them away from a precipice, so the buddhas have to show wrathful forms in order to train those beings who are not able to respond to a more gentle approach in some particular situation. However, the underlying intention that is found in the wrathful rituals of the dharma protectors is one of the greatest love and compassion.

10. How do we choose a yidam?

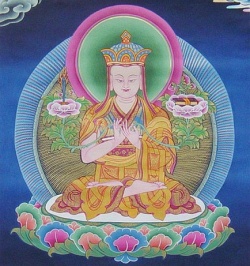

In the tantric system the term ‘yidam’ refers primarily to the deity upon which we meditate. It should be pointed out that it is not always entirely a matter of us choosing yidams. Sometimes, particularly in the earlier part of our dharma career, we are more likely to simply practise the deities suggested to us by our masters. They will often prescribe whichever deities are regarded as most important in their tradition. Each of the four traditions preserves particular meditation systems associated with particular deities, although there is a great deal of commonality. For instance, across the four traditions it is usually the case that the beginners in vajrayana will practise deities such as Chenrezik, Tara and Manjushri. These deities are easily approachable and the qualities they embody, such as compassion and wisdom, are very useful for us in starting out on the vajrayana path. Then, if we fully go through the systematic yogic training of whichever one of the four schools we are following, it is likely that we will eventually spend at least some time meditating on the deities that are particularly emphasized in that tradition, for instance Vajrayogini and Hevajra in Sakya or Vajrakilaya in Nyingma.

Choosing a yidam is usually something that evolves over a long period of time. When we have meditated on quite a few different deities over the course of our dharma practice, we will gradually develop a connection with a particular deity. That occurs when a certain deity is related to our deepest spiritual needs, the way in which we are best able to relate to ultimate reality. One need not worry, therefore, about which yidam to practice. Follow whatever your teacher suggests and gradually your affinity with a particular deity will reveal itself. It may be after two or three years; it may be after twenty. There is no particular time scale involved.

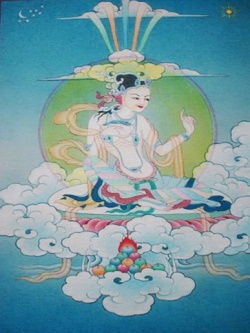

11. Is there a rule that men practise male yidams and women practice female?

There is no rule regarding this. Many men meditate upon the female deities Tara and Vajrayogini, and many women meditate upon male deities. For instance, the main yidam of Yeshe Tsogyal, the great yogini who was the consort of Guru Padmasambhava, was the male deity Vajrakilaya. It is also true that some great yoginis have specialized in the meditation of female deities such as Vajrayogini. In the Sakya tradition great yoginis often tend to concentrate more on the female deity Vajrayogini than on the male one, Hevajra, but again there are many exceptions to this.

Although buddhas may show themselves as male or female, in actual fact our buddha nature encompasses both male and female. The essence of enlightenment is non-duality. Furthermore, within all beings there are the elements of both male and female. So though the outer form of a buddha appears as either male or female, enlightenment is only achieved through reconciliation of both these aspects of our being.

12. How can it be compassionate if we just sit on our meditation cushions without doing anything? How does this help other beings?

It is not that we are doing nothing. We are training in the skilful means that will finally enable us to benefit others. One might just as well say that medical students who spend seven years in medical training before going out to operate on people are wasting their time in doing so. Of course they are not, because it is only that long training which will equip them with the means to benefit others, instead of treating people prematurely and probably causing harm. So it is with the training of dharma. We need daily meditation, periods of intense study and meditation retreats. Whether it can be said to be compassionate comes down to the motivation. As Buddha said, motivation is the most important factor in determining the value of any action. If we have the right motivation in undertaking spiritual training, then even sitting in silence or going into solitary meditation retreat are acts that will have an immensely positive outcome for others.

I must also add that those who are very accomplished in meditation are able to benefit others even when they remain in retreat. They can do this through their prayers and the extension of their benevolence to sentient beings. So we should not think that hermits or great meditators are in some way cut off from the world, whilst we are fully integrated with it. Their prayers can and do aid us even now.

13. There are many rituals in vajrayana such as prostrations, circumambulations and so on. Are they not somehow too Tibetan for us Western people?

The first thing to note here is that they are actually not Tibetan in origin but Indian. This is a very important point because there was a distinction between the culture of India and the culture of Tibet in the eighth century, just as now there is a gap between Tibet and our own culture. India was in many respects a sophisticated South Asian caste-based society and Tibet was a rather simple Central-Asian nomadic pastoralist society. There was probably nearly as much difference between those two societies as there is between any Asian society and the modern Western one.

The essential point is that Buddha’s teachings go beyond culture. He prescribed all kinds of spiritual methods, including physical techniques such as prostrations and circumambulations, as ways to combat various negative tendencies that occlude our true nature. For instance, prostrations are a great remedy for pride. Do we really think Westerners are more humble than Tibetans or Indians? I doubt that very much. By prostrating we are engaging with devotion to the Three Jewels in a very unambiguous way. We are not simply paying lip service to the Three Jewels but actually developing openness and humility through our very body. Therefore, it is an effective method for developing the qualities for which we strive. Kalu Rinpoche used to say that he could see no important difference between Tibetans and Westerners. As he put it, ‘The true nature of mind, the buddha nature, is the same in Tibet and the West and likewise it is covered by the same obscurations in both places.’ In the light of this one might well ask what is the real difference? We might have a few more computers in the West but otherwise we are not so different.

14. Why, in some Buddhist centres in the West, including yours, do people recite their prayers in Tibetan and not English?

There is no strict rule here and even in our centres, there is actually a mixture. When in groups, people generally use the Tibetan but sometimes people do their prayers in English at home. This is still a period of translation in the West and with all respect to those who are engaged in translating, I do not think that anybody would claim that we have yet arrived at definitive translations of any of the texts, whether they are the great philosophical treatises or the basic prayers that people use in their daily practice. So in order that we do not distort the meaning of these texts by arriving at a premature, incomplete or even erroneous translation, it is better to signify the provisional nature of these translations by not discarding the Tibetan. This may sound like we are moving towards the period when all the practices will be done in English and that might well be the case. There is nothing intrinsically sacred about the Tibetan language. When Buddhism came to Tibet from India, only the mantras of vajrayana were kept in Sanskrit. The rest of the Sanskrit material was translated into Tibetan and in translating from Tibetan to English, the same approach would be applied.

15. With which lamas do we have samaya?

As we have seen earlier, samaya is the bond or commitment that is created when we take an initiation. Whichever level of tantra it may belong to, an initiation introduces us directly to the aspect of our buddha nature that is embodied in the form of the deity. From then on, there is a connection that exists between the deity, the lama who bestows that deity, and the person who receives the initiation.

There are many aspects of samaya in vajrayana but the most crucial one is the relationship with the lama. We must try from the time of initiation onwards to see him or her as inseparable from the deity. After all, it is only the extent to which he is identical to the deity that enables him to introduce us to that deity in the initiation. Even if it is a lama from whom you only take one initiation and subsequently never see again, you still have samaya with that lama from then onwards. That samaya is expressed at the end of each initiation when the disciple repeats the words, ‘As the master commands, so I will do.’ Everybody who has received vajrayana initiation has repeated those words since all initiations conclude in this way.

Whomever you take an initiation from is your vajra master. That means of course that you can have many vajrayana masters in your life. Obviously, one or two of them will be of the most significance to you. They are the ones from whom you take the essential guidance that affords you success on the spiritual path. This does not diminish the fact that any master from whom you have received a vajrayana initiation is your vajrayana master and you have samaya with him. Regardless of whether or not you consider them one of your principal lamas, the consequences of breaking samaya bestowed by a lama are severe. To break samaya with one’s master is to turn one’s back on the enlightened energy that was transmitted to one during the initiation. By doing so one alienates oneself from the spiritual path.

16. If one has received many initiations, is it necessary to practice the sadhanas of all of them?

It will not actually be possible to realize the qualities of any of the deities if one tries to practice too many of them. As it is said in Tibet, ‘If you try to practice a hundred deities you will not get the benefit of one. Yet if you practice effectively just one, you will get the benefit of one hundred.’ So, although we may receive an initiation, it might well be our master’s advice not to rely upon that deity at that time. One may then ask why people take many initiations. There are two answers here. The first reason is that it is beneficial to take initiations because they renew one’s vows. If there have been breakages of vows or the samayas of previous initiations, these are purified by each initiation one takes. The second reason for taking initiations is that one might well need to rely on this deity at some time in the future, even if it is not appropriate now.

17. If you have taken initiations and vows with a teacher who you later discover was not qualified, are you still bound to the commitments you have made?

Sakya Pandita says that we are not bound by vows to such people because they have not been able to bestow anything genuine upon us. However, one must be careful about this. Having taken an initiation from a fully qualified lama, if one later becomes contemptuous of him, one has committed the first root downfall of vajrayana. Thus, having received initiations from a fully qualified master, it is essential that one continues to perceive him with pure vision. In this respect it is very helpful to rely upon the regular practice of guru-yoga in which one visualizes one’s master as a buddha.

There are stories of great masters who sometimes behaved in ways that were absolutely contrary to normal expectations. For example, the way that some teachers like Tilopa treated their students in order to cause them to recognize the nature of their mind sometimes involved actions and instructions that might appear shocking. If a fully qualified master behaves in that way towards us, we must maintain a pure view of him and his teachings.

18. Some people take initiations without actually knowing what they have got involved in. Does this make the samaya less serious?

I am afraid that in Buddhism ignorance is not an excuse. In the ‘Fourteen Downfalls of Vajrayana’ Jetsun Drakpa Gyaltsen specifies ignorance as one of the four causes of breaking vows. The other three are lack of respect, lack of vigilance and being under the influence of the mental poisons. The point is that one has responsibility for a breakage even if the cause was ignorance. Perhaps one can say that it is the least meretricious of the motivations and so the consequences might be somewhat less than a breakage caused by, for example, hatred. Nevertheless, one would still have broken the sacred vows.

19. When we read the biographies of Indian and Tibetan teachers from the past, sometimes these sound rather unrealistic. How much is true and how much has been added by their students as an act of respect?

There are actually different types of biographies found in dharma. For instance, in Tibet most biographies and dharma histories were written in a very precise fashion, being concerned primarily with recording the master’s training, the various teachings he or she received and to whom they were transmitted. Having said that, in many of the biographies of the great Indian yogins far less attention was given to notions of historical accuracy than was given in later Tibetan texts. Furthermore, certain texts, such as the ‘treasure’ texts concerning Guru Padmasambhava, could be understood as being a kind of mixing together of external events and the inner landscape of spiritual experiences. On a subtle level such biographies explain how great masters dealt with the various crises that arose on the spiritual path, how these were resolved, and how spiritual power was developed. In other words, they are more concerned with spiritual events than with providing an accurate chronology of external events. Are these true? Of course they are true, in the sense that they give us a consistent, spiritually powerful and beneficial account of the spiritual path, as displayed in the life and experience of these great masters.

20. Can meditation help people to stop taking drugs?

Meditation cannot help people to stop taking drugs. People cannot meditate until they stop taking drugs. Meditation can only help in the sense that if one has a sincere desire to meditate, one will remove any obstacles in one’s life that prevent one from doing so, and one will therefore stop taking drugs. It is a question of whether one values a life of self-indulgence, or whether one values practicing the dharma.

21. Are the experiences of taking drugs the same as the experiences of meditation?

Certain drugs, the so-called psychedelic ones, are particularly acute in the way they can trigger off experiences which may mimic meditative states. However, the person in whom these experiences arise has neither renunciation nor bodhichitta and lacks the discriminative wisdom with which to be able to utilize these experiences. Therefore, the most one can say is that they are like the dream of a spiritual experience rather than the experience itself. One must concede that occasionally what we experience in a dream motivates us to seek it in waking life. That could be why from time to time drug experiences trigger off a spiritual search in people. However, times move on and it seems more and more the case that drugs are revealing their true face, which is a destructive one. They damage not only people’s spiritual capacity but, as we can often see, the fabric of society itself.

22. There are many books about tantric sex. Could you explain more about this?

Most of these books about tantric sex are just money-spinning enterprises that have nothing to do with anything spiritually or even historically authentic. One can say that the entire vajrayana is concerned with the transmutation of sense experience into the path to enlightenment. Sense experience is not itself intrinsically impure but is made so by the impure projections of the deluded mind. In vajrayana we try to experience the underlying purity of whatever actions we engage in by using such methods as visualization of ourselves and others as deities. This pure vision is the core of the vajrayana and expresses the inseparability of samsara and nirvana. As we have seen earlier, the meditations of anuttara tantra are divided into the development and completion stages. In the latter there are practices based upon the subtle body comprised of winds, channels and drops. Through such practices as tummo we strive to bring about an experience of great bliss through this subtle body. Although most of these completion stage yogas are accomplished by the yogin in solitude, there are some completion stage yogas that are to be done in conjunction with a consort. In some cases, this consort is visualized, but at other times he or she can be an actual physical person. In that case, the partner must be fully consecrated by initiation and maintain all the samaya vows. In order to be able to perform these practices, the yogin must have a considerable mastery of the other completion stage yogas. Such practices are therefore rare and are practiced with a great deal of secrecy. Moreover, such practices with a consort are not permitted to monks or nuns, since they would contravene their vows of celibacy. Certainly, no genuine instructions for these types of yoga have been published in Western languages, despite the fact that there are two or three books that pretend to reveal these secret teachings.

23. The Tibetan Book of the Dead is very popular in the West nowadays. Do you think that Westerners who are not Buddhist should read it?

One must ask whether there is any point in them doing so because this teaching, actually called the Bardo Thodrol, depends on the acceptance of the doctrines of rebirth and intermediate state. This text explains how we can obtain liberation during the processes of dying and rebirth. Thus, if you do not believe that consciousness continues after death, this teaching would be merely a quaint curiosity.

Perhaps it is useful to explain a little more about this subject, since it is an important one and provokes a great deal of speculation. The word ‘bardo’, or intermediate state, literally means ‘that which lies between’. In this case it refers to the gap which lies between the moment of death and the subsequent moment of rebirth, or more precisely conception. In the tantras, especially those of the Nyingma school, it is explained that at the moment of death one’s consciousness is reunited with the ground of all awareness, sometimes known as ‘the mother luminosity’. At that moment there is an opportunity to recognize our primordial nature, the dharmakaya itself. In most cases, however, due to the weight of the imprints of past actions, we fail to recognize the luminosity of reality and fall into a kind of faint.

Subsequent to the moment of death and immediately upon the consciousness being precipitated out of the body, there is a second encounter with the clear light of ultimate reality followed by a further period of unconsciousness, a kind of swoon, after which we awaken within the bardo itself. In the bardo we undergo various encounters with our primordial nature, experienced as a series of peaceful, semi-wrathful and wrathful deities, all of whom are manifestations of the basic radiance of our mind. With each of these repeated encounters, there is an opportunity for us to gain liberation by recognizing that this deity is nothing other than a projection of our own mind. Here again, the propensities of ignorance are so strong that in most cases we do not recognize them. Thus we progress through the bardo until we reach its final stage, known as the bardo of becoming. This is like the ante-chamber of rebirth. At this point, the effects of our past karmic activity have reasserted themselves and start to shape the pattern of our future life. If at this time we can cut through the chains of karma, we can prevent rebirth into an unfortunate state and instead take a compassionate rebirth to benefit others. If we cannot cut through the chains of karma in this manner, it is inevitable that we will be driven on to conception by the power of our previous actions. For most beings there is no element of personal choice here. We are simply propelled into rebirth by our imprints. The bardo comes to an end at the moment of conception when the consciousness of the being in the intermediate state fuses with the sperm and the ovum of their future parents.

Though this teaching is explained in various tantras, the most detailed account of it is found in the Bardo Thodrol , a collection of treasure-texts concealed by Guru Padmasambhava, which was discovered and disseminated by the treasure revealer Karma Lingpa in the fourteenth century. This is what has become popular in the West under the erroneous name of The Tibetan Book of the Dead. In the Nyingma tradition these teachings are given as a kind of appendix to the teachings of dzok chen. It is said that through dzok chen we can recognize the true nature of mind in this very life and therefore do not have to enter into the bardo. If we cannot achieve this level of realization during our lifetime, then the technique known as phow a , or consciousness transference, affords us the opportunity to achieve liberation of the moment of death through uniting one’s mind with the Buddha Amitabha and obtaining rebirth in his pure realm. However, if we have not gained mastery of phowa, we will have to rely on the teachings we have been given on the bardo. So in this sense there are three opportunities for liberation provided for us: first, during life through dzok chen teachings; secondly, at the moment of death through phowa; and thirdly, at the moment following death, through the bardo teachings.

24. Who are the revealers of the treasure-teachings and how do we know if they are genuine?

Recognizing that people in future generations will have particular specific needs and difficulties to overcome, Padmasambhava, aided by his disciples Yeshe Tsogyal and Vairochana, concealed a large number of esoteric instructions in the form of cipher manuscripts and sacred objects in various places throughout Tibet. These have been discovered at the predicted times throughout the centuries by the so-called ‘treasure revealers’ (tertons) who are recognized as emanations of the original 25 major disciples of Padmasambhava. The treasure revealers, who discovered, decoded and disseminated these teachings, were blessed by Guru Padmasambhava to discover them in their former lives as his disciples. They were not ordinary people who chanced upon or made up these teachings, or archaeologists who simply translated some formerly forgotten texts. Someone might claim to be a treasure revealer but only the treasures that have spiritual efficacy can be judged to be authentic. Padmasambhava himself acknowledged that there would be ten false treasure revealers for every genuine one. That is why in Tibet a great deal of care was always taken in assessing whether a treasure revealer was genuine. Accomplished masters would examine the teaching and only when they confirmed its authority, would it be accepted. For instance, when Chogyur Dechen Lingpa (1829-70) first revealed his treasure teachings, they were carefully checked by Situ Rinpoche of Palpung before he was acknowledged to be a genuine treasure revealer.