Funeral Rites Across Different Cultures

Responses to death and the rituals and beliefs surrounding it tend to vary widely across the world. In all societies, however, the issue of death brings into focus certain fundamental cultural values. The various rituals and ceremonies that are performed are primarily concerned with the explanation, validation and integration of a peoples’ view of the world. In this section, the significance of various symbolic forms of behaviour and practices associated with death are examined before going on to describe the richness and variety of funeral rituals performed according to the tenets of some of the major religions of the world.

The Symbols of Death

Social scientists have noted that of all the rites of passage, death is most strongly associated with symbols that express the core life values sacred to a society. Some of the uniformities underlying funeral practices and the symbolic representations of death and mourning in different cultures are examined below:

The Significance of Colour

When viewed from a cross-cultural perspective, colour has been used almost universally to symbolise both the grief and trauma related to death as well as the notion of ‘eternal life’ and ‘vitality’. Black, with its traditional association with gloom and darkness, has been the customary colour of mourning for men and women in Britain since the fourteenth century. However, it is important to note that though there is widespread use of black to represent death, it is not the universal colour of mourning; neither has it always provided the funeral hue even in Western societies.

White is considered appropriate in many cultures to symbolise purity, as well as, in some religions, oneness with God, or eternal life in others. Sikh women generally wear white clothes for mourning, although sometimes they wear black. Though there are variations within the Hindu traditions, women generally wear white or black. Even though there is sorrow in death, if the deceased person is elderly, black or white may not be worn as they have lived a long and fulfilled life. White has also been a popular colour of mourning at Christian funerals at different periods in history, a notable example being Queen Victoria’s funeral.

The colours and clothes in which the deceased are dressed are often indicative of age, marital status and caste. Amongst Hindus, if the deceased is an elderly male, the clothing tends to be simple and is normally white. Married women are dressed in new saris in shades of red and pink, as these are considered to be auspicious colours. Some items of jewellery, especially the mangal sutra (tied around the brides neck at the time of marriage by her husband), are left on the dead body and red kumkum powder is placed in the parting of the hair. In stark contrast, deceased widows are generally dressed in sombre shades.

Sikh families choose the clothes the deceased is to wear. For men, these may either be a western suit and turban (white, black or coloured) or a Punjabi suit and turban. Women will be dressed in a Punjabi suit, younger women in bright colours and older women in paler colours. The deceased is wrapped in a white shroud and a rumalla (a special silk cloth, of the same type used to cover the Guru Granth Sahib, (often in a bright colour), is placed over the top.

The Symbolism of Hair

Another widespread feature of funeral and mourning customs and one that is closely allied to clothing and styles of endowment, relates to the mourners’ hair.

Jews, for instance, observe strict mourning for seven days. During this period, male relatives of the deceased are forbidden to shave their beards.

Among Hindus, the ceremonies following a death usually last for thirteen days. However, on the eleventh day closer male family members of the deceased shave their beards and heads.

The Ritual Significance of Food

In many cultures, an important aspect of funeral rites in concerned with ensuring the safe and comfortable passage of the soul from life into death.

Amongst Hindus, relatives of the deceased traditionally eat only simple vegetarian food for thirteen days following a death. Funeral ceremonies culminate in a feast, its grandeur varying according to the age and social status of the deceased.

The tradition of feeding the mourners after the funeral is quite widespread, signifying the continuity of life and of communal solidarity. The food that is served at such ceremonial gatherings tends to be highly symbolic. For example, Jewish mourners returning home from a funeral are normally given a hard boiled egg as a symbol of life.

Among Chinese in Hong Kong an all-night memorial mass may be said, in which both Taoist priests and Buddhist nuns may play a role. Part of the ritual involves calling out the dead person’s favourite foods in order to tempt the departed soul to return. At daybreak a paper house, banknotes and paper clothing are burnt for the soul’s use in the next life. All mourners present at the ceremony eat baked meats. Later the death room is thoroughly cleansed and purified.

Emotional Reactions to Death

Death evokes a variety of emotional responses, but the range of acceptable emotions and the extent to which the grief and sorrow experienced by mourners are allowed free expression are tied up with the unique institutions and values of each society. The emotional tenor at funerals in England and other Western European societies tends, on the whole, to be rather low-key. While it is quite permissible for female relatives and other mourners to cry at funerals, the excessive display of grief in public is generally an embarrassment for both the bereaved and the comforter. In contrast, in some other cultures crying at funerals is not merely tolerated, it is required by custom, and at predetermined moments during the ceremony, the entire group of mourners may burst into loud and piercing cries.

In Ireland, close relatives of the deceased usually wept over the body during the wake. Although the practice of ‘keening’ or loud lamenting is rather less widespread than it used to be, it is still quite common to hire professional mourners to compose eulogies over the dead. The eulogy is accompanied by loud wailing. To Orthodox Jews, being properly lamented over is almost as important as being correctly buried.

Among Hindus and Sikhs, families gather to share the mourning. On the day the person dies, the family living room is turned into a mourning room: white sheets are placed on the floor and friends and family will visit. Other family members will bring food for the mourners to eat. After the cremation, people begin to return to their usual daily routine. In Sikh families, a sehaj path (a broken reading of the Guru Granth Sahib) is held either in the home or the gurdwara.

Funeral Customs and Death-Related Rituals

The funeral customs and death-related rituals of some of the major religions will now be discussed in more detail.

Buddhist Beliefs and Practices

There are about 200,000 Buddhists in the UK. Many are born into the faith as members of immigrant families from Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, Tibet, China or Japan, but some are British-born converts from other religions. There are three main schools of Buddhism – Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana – and all are found in the UK.

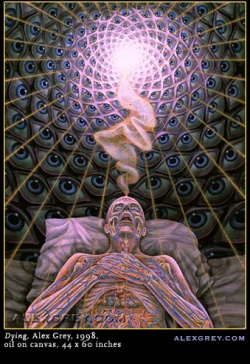

Buddhists believe that they live a succession of lies; samsara is the word used to describe the endless cycle of birth, death and rebirth in various states (e.g. human, divine, animal, etc.) and in many different planes (e.g. happy, unhappy). Life in samsara continues until the believer attains an enlightened state of permanent, lasting happiness called nirvana: the ultimate goal of all Buddhist practice. Death is seen as a prelude to existence in another state. According to Buddha’s teaching, no state lasts forever. The plane of rebirth is determined by a person’s karma, which is the sum total of wholesome and unwholesome actions performed in previous existences. In order to reach enlightenment the Buddha’s teachings, called the Noble Eightfold Path, should be followed. Until this state is reached we continue circling on in samsara.

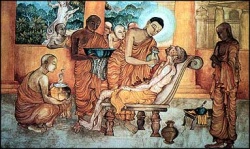

Buddhists place great importance on the state of mind at the moment of death. When death is imminent a monk is called to chant from religious texts, or relatives may introduce some religious objects to generate wholesome thoughts into the person’s mind, because the last thought before death will condition the first thought of the next life.

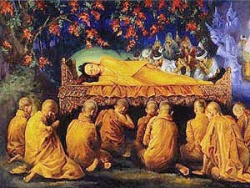

One, two or three days after death, the body is either buried or cremated. At the funeral monks lead the congregation in the traditional Buddhist manner, offering respect to Buddha, the Dhamma (his teaching), and the Sangha (the community of enlightened beings). Following this, the congregation accepts the Five Precepts, which are guidelines for – and commitment to – the leading of a moral life.

If a cremation takes place, it is traditional for a nephew of the deceased to press the button that draws the curtain on the coffin and consigns it to the furnace. Sometimes the ashes are kept in an urn, which may be stored in a monument built specifically for this purpose; alternatively they may scattered.

Immediately after the death, friends and relatives observe a period of mourning. This is done symbolically by observing a certain amount of austerity and frugality in the house of the dead person. Mourners may, for example, wear plain white clothes, abstain from wearing jewellery, eat simple food and not indulge in entertainment.

Relatives and friends direct their efforts above all to assisting the deceased in his or her journey through samsara. By performing good actions such as unselfish generosity, they generate ‘merit’, which can be transferred to benefit the deceased. This is the primary way of showing one’s gratitude and paying respect to the dead. This act may be repeated three months later and then annually thereafter. In addition to benefiting the deceased it also brings comfort to the bereaved. Before the end of the first week after death, a member of a monastic community may be invited to the house to talk to the surviving members of the family. They will usually remind the bereaved that everything is impermanent, that nobody can live forever and death is inevitable. Buddha, however, cautioned his followers that expressions of grief may be damaging to one’s mental well being, causing pain and suffering. He said that grief does not benefit the departed one, nor does this benefit the griever.

Summary

- Buddhists believe in an endless cycle of existence until and unless Enlightenment is attained.

- Death is merely a prelude to existence in another state.

- Everything is impermanent and no state lasts forever, apart from Enlightenment.

- The main efforts of mourners are directed towards smoothing the passage of the deceased in the subsequent existence.

- Merit transferring ceremonies may be held regularly, such as on the anniversary of the death.

Christian Beliefs and Practices

There are over six million Christians in the UK who regularly attend church. They are divided into denominations that are distinguished by various differences in doctrine and worship.

Christians believe in one God who has revealed himself as the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. This is described as the Holy Trinity. Central to Christian belief is Jesus of Nazareth in whom God assumed human form. The sacred text for Christians is the New Testament, which contains a code for living based on the life and teaching of Jesus. The resurrection of Jesus- when he returned to life after being crucified – is integral to the belief in Jesus’ claim and offer of a life after death in heaven. Depending on the aspect of the central mysteries stressed by a particular Christian tradition, death can produce feelings of fear, resignation or hope.

After death the body of the dead person may be moved to the undertaker’s Chapel of Rest. The word ‘chapel’ does not necessarily indicate a place of worship, though in the case of believers the Funeral Director often arranges candles round the coffin and displays a cross.

Some Roman Catholics or High Church Anglicans transfer the corpse to their church on the evening before the funeral; following the ritual reception of the body into the church, it remains there overnight. In some parts of the country, however, the coffin is brought to the house the evening before the funeral and transported from there to the church. The next morning a funeral service or requiem mass is celebrated during which the priest or minister wears black vestments.

The final ritual in Christian burial is the graveside committal where the minister leads the mourners in prayer as the body is lowered into the grave.

Instead of burial, some Christians may choose cremation. The ashes of the deceased may be scattered in a Garden of Remembrance or elsewhere. Alternatively, they may be placed in an urn and interred in a cemetery. Some families keep the ashes at home. If the ashes are to be scattered in the Garden of Remembrance, the family may choose the garden and the precise place of dispersal, and if they wish, they may return a few days later to witness the scattering of the ashes.

Summary

- Christian belief and practice is based on the mysteries of incarnation and resurrection.

- Belief is in one God and Jesus of Nazareth in whom God assumed human form.

- Personal identity is retained after death.

- Human beings are in continuing fellowship with God throughout life and death.

- Some Christians maintain a clear belief in heaven and hell.

- Roman Catholics believe in a state called purgatory – a place where a soul is purified in preparation for entry into heaven.

- A person lives only one physical life.

- The body is placed in a coffin by an undertaker and subsequently taken to a church or crematorium. Following a memorial service the body is buried or cremated.

- Flowers may be used in the form of wreaths. These are traditionally rounded to symbolise continuity and eternity.

Hindu Cremation Customs and Rites

There are an estimated 800,000 to one million Hindus in the UK, the majority of who are from India, East Africa, Malawi and Zambia.

Hindus believe in the law of karma which states that each individual passes through a series of lives until, depending on the actions of previous existences, the state of moksha, or liberation from the cycle of birth and rebirth, is attained. Consequently, death is not understood to be the end of a process, but is merely a stage in the long chain of transition. It is this continuity, extending beyond the limits of any single lifetime, which is enhanced and focused during the elaborate mortuary rituals performed by Hindus. The funeral ceremonies involve not only the immediate family members of the deceased, but also those of the extended kin network. Particular categories of kin have special ritual and economic duties to perform on this occasion. There are many regional and sub-cultural variations in the content and duration of mourning practices; the following is limited to describing the ceremonies in the broadest terms.

When death is imminent, the person is lifted from the bed to the floor so that the soul’s free passage into the next life is not obstructed. Water from the holy River Ganges is given to the dying person and a tulsi (basil) leaf is placed in the deceased person’s mouth. The tulsi leaf has a dual significance. Firstly, it is associated with Lord Vishnu, one of the three gods who are collectively known as the Hindu Trinity of gods; Vishnu is also known as the preserver of the universe. Secondly, the tulsi leaf is believed to have many medical properties.

After death, the body is washed and dressed, preferably in new clothes. Married women are clothed in a pink or red sari and adorned with jewellery. Kumkum red powder is placed in the parting of the hair and a red spot or tilak is applied on the forehead. The woman’s father or brother usually provides the clothes, and when a man dies, the clothes are again provided by the wife’s father or brother.

In India, the hot climate necessitates that the funeral is held as soon after death as possible; however in Britain the need to fulfil various legal and bureaucratic formalities may lead to a delay for a few days.

Except for young children under one year of age who may be buried, the customary mode of disposal of a dead body amongst Hindus is by cremation. In the villages in India, the body is placed on a bier made of bamboo poles and carried on the shoulders of close male relatives to the burning grounds. In most cases, all the relatives in the village attend the cremation. The actual size of the gathering of mourners varies with the age and importance of the deceased. Thus, when an elderly and highly respected man dies, even his genealogically and geographically distant family would make it a point to attend the cremation.

The nearest male relatives of the deceased, such as the father, husband, brother or son, are generally forbidden to shave or cut their nails for eleven days following the death. This custom, however, varies in different parts of India; in Gujarat and some other parts of Western India, the nearest male relatives of the deceased are required to shave their heads on the actual day of the death.

There are now electric crematoria in many cities in India, including one near the bank of the River Ganges in Varanasi. At cremation grounds, or ghats, the body is placed on a pyre of wood with the head pointing north in the direction of Mount Kailasha in the Himalayas. In the case of affluent families the wood of the pyre may be an expensive variety such as sandalwood. ‘Ghee’, or clarified butter, is poured on the pyre to help it burn, and the pyre is then set alight by a son, brother, or brother’s son (in this order of priority). Other mourners will then throw fruit, flowers, incense and fragrant spices into the fire. Mourners traditionally attend the entire cremation, i.e. until the body has been totally consumed by the fire. In the final stages of this long process, the chief mourner (i.e. the male relative who first lit the pyre) breaks the skull with a long pole in order to allow the soul to escape, a rite know as kapol kriya. On the fourth day (in certain parts of India this may take place on the third day) the ashes are collected by the chief mourner and the place of cremation cleared. The ashes are then traditionally immersed in a river, preferably the Ganges. Any items of jewellery that have not melted in the fire are collected and distributed among the mourners, along with a simple meal, usually a food called kitcheree, a mixture of boiled rice and lentils.

In Britain, the dead body is transported in a coffin to the local crematorium. The Funeral Director can arrange to have the ashes collected and scattered in the crematorium’s Garden of Remembrance or stored in an urn until the relatives of the deceased arranged to have it transported to India.

Among Hindus, both in India as well as in Britain, the ceremonies following a death normally last for thirteen days, but the ritual pollution incurred by the close family members is terminated on the eleventh day. The chief mourner performs a rite, aided by a Brahmin (priest), and the male relatives present their hair and beards. On the thirteenth day the mourners offer a blessing to the deceased to show gratitude for acts of kindness they received during their lifetime. Throughout the thirteen-day official mourning period, relatives are required to eat only simple vegetarian food and generally to lead a secluded life. The custom of friends and relatives visiting to mourn is also practised.

Even after death, the deceased person is still regarded as part of the family and their names will often be included, for example on invitations to the wedding of children or grandchildren. The death anniversary is usually observed with a special meal. Within a family, a picture of the deceased parents may be kept in the home shrine and it is usual to garland the picture.

Summary

(please note that there is tremendous diversity within Hinduism, and there are many regional variations.)

- Hindus believe in reincarnation and that at death the soul sheds its body and ‘puts on’ another body (not necessarily human) in a cycle of re-birth until it reaches God.

- In India the body is usually cremated within 24 hours of death. It is wrapped in a cloth and placed in a coffin. The coffin is covered in flowers.

- By tradition, the eldest son should set the funeral pyre alight, or press the button if a crematorium is used.

- The eldest son and other close male relatives have their heads shaved as a sign of bereavement and cleansing.

- Friends and relatives keep the bereaved company, share grief and offer support.

- On the eleventh or thirteenth day all will gather to offer a blessing to the deceased in order to show gratitude for acts of kindness that they received during his/her lifetime.

- Memory is preserved in the family’s daily prayers (puja).

Humanist Beliefs and Practices

Humanists believe that we only have one life and that we should make the best of it. We should try to live happy and fulfilled lives and help others to do so and the best way to achieve this is by living responsibly, thinking rationally about right and wrong, considering the consequences of our actions and trying to do the right thing. Humanists are concerned with making the world a better place in which to live, not only for people alive today, but also for future generations – especially as the lives of their descendants represent the only sort of immortality in which humanists believe.

Humanists ask themselves the same questions as everyone else: Why am I here? What’s the purpose of life? How did life begin? What will happen to me when I die? They look for evidence before they take on a belief, and so are more likely to believe the results of scientific research or what their own experiences tell them – or remain open-minded about questions – rather than to believe what someone else says. Humanists tend to think about these big questions for themselves. Some questions may not have answers, or we might not like the most probable answers.

Humanists experience the same feeling of loss and sadness at the death of a loved one as anyone else does. But they accept death as the natural and inevitable end to life. They do not believe in any kind of life after death, but believe that we live on in other people’s memories of us, in the work we have done while we are alive, and in our children.

Humanist Funeral Ceremonies

There are no specific or obligatory rituals to be followed either by the bereaved or by those who wish to express their condolences. An expression of sympathy, an acknowledgement of the bereaved person’s feeling of grief and the offer of a listening ear are more likely to be appreciated than any suggestion that the deceased has gone ‘to a better place’ (which may contradict what the family believe). Humanists may choose to be cremated or buried and the ceremony can take place anywhere, though it is most commonly held at a crematorium where, if possible, any religious symbols will be removed or covered up.

At a humanist funeral there will be no suggestion that the deceased has gone on to another life: the ceremony is intended to celebrate the life that was lived. The humanist funeral officiate will have spent time with the bereaved relatives and together they will have planned a ceremony that properly honours the person’s life and, hopefully, brings some comfort to everyone who attends as they are reminded of how their lives have been enriched through knowing the deceased. At the funeral, the officiate will talk about the person’s life and what they achieved and it is usual for family members or friends to read personal tributes. The ceremony may also involve suitable readings, poetry or music, and there may be a brief period of silence to allow people attending the ceremony time for their own private reflection or – if they are religious – for prayer.

Summary

- Humanists believe that there is one life and that we should make the best of it by living happy and fulfilled lives and helping others to do so.

- They look for evidence or draw on their own experience – rather that believe what someone else says – in order to form their beliefs and answer questions.

- They accept death as the natural and inevitable end to life. They do not believe in life after death, but rather that people ‘live on’ in other people’s memories of them.

- There are no specific or obligatory rituals to follow at deaths or funerals; however expressions of sympathy and the acknowledgement of the bereaved person’s feelings of grief are appreciated.

- Humanist may choose to be cremated or buried, and the ceremony can take place anywhere. If possible, all religious symbols (e.g. at a crematorium) are removed or covered.

- The funeral ceremony is intended to celebrate the life that was lived and properly honour that person’s life. Through readings, poetry, music and personal tributes from family and friends, attendants are reminded of how their lives have been enriched through knowing the deceased.

Jewish Funeral Customs and Beliefs about Death

Jews believe in one God who created the universe. The Jewish Sabbath begins at sunset on Friday and ends an hour after sunset on Saturday, and commemorates the seventh day when God rested after the Creation. During this time religious Jews do not travel, write, cook, or use electrical equipment.

Unless death occurs after sunset on Friday, in which case the burial is postponed until Sunday, the Orthodox Jewish tradition prescribes that funerals should take place within twenty-four hours. Professional undertakers are involved since all arrangements are made through the Synagogue. The body is dressed in a white shroud (kittel), which is then placed in a plain wooden coffin. Men are buried with a prayer shawl (tallith) with its tassels cut off.

While the body is in the house, Jews believe that it should not be left unattended. Candles are placed at the head and the foot of the coffin and sons or other near relatives of the deceased maintain a constant vigil. If no relatives are present, professional mourners are called in.

The rabbi is sent for as soon as death occurs. He or she returns to the house of mourning an hour or so before the funeral is due to start to offer special prayers for the deceased. Close relatives of the dead person usually gather at the house of mourning, dressed in old clothes from which a piece is ritually cut as a mark of grief. Traditionally this torn garment is worn throughout the seven days of intensive mourning (shiveh).

After prayers offered by the rabbi at the house, the coffin is carried out and mourners usually follow on foot to the cemetery. If the cemetery is not within walking distance, transport is permitted, but many Orthodox Jew insist on covering at least part of the way on foot.

Progressive liberal Jews permit cremation. However, according to the orthodox tradition, cremation is forbidden, as human beings are created in the image of God and it would therefore be wrong to deliberately destroy a body. At the cemetery the dead body is taken to a special room. Mourners usually wait outside until the coffin is placed in the centre of the room. Then the men stand on the left and the women stand on the right of the coffin. There are no flowers or music at the funeral ceremony, ensuring that there is no distinction made between rich and poor. Prayers and psalms are recited and the rabbi makes a special mention of the virtues of the person who has died.

The coffin is then carried to the grave followed by the mourners. The sons and brothers of the deceased shovel some earth on the coffin. After the burial the special prayer for the dead, the Kaddish is recited for the first time by the male relatives. A special meal is provided of eggs, salt-herrings and bagels. Peas or lentils are also a suitable food to serve on this occasion as, according to Jewish tradition, roundness signifies life.

In orthodox families, from sunrise to sunset during the seven days of intensive mourning, close relatives of the deceased must wear their torn garments and special slippers that are not made of leather. Prayers are said throughout the day. Neighbours and friends visit to offer condolences and help.

The ritual prescribed for women ends with this seven-day period. Men however, are forbidden to cut their hair or shave for thirty days. The sons or other male mourners go to the Synagogue every day to say the Kaddish for eleven months. The gravestone is then erected, symbolising the end of the official period of mourning.

Every year on the anniversary of the death, the family say the Kaddish and burn a candle for twenty-four hours. The grave is visited at least once a year, especially before the Jewish New Year, to ensure that cherished memories do not fade.

Summary

- Jews believe in one God and that there is only one life to be lived.

- After death the body is washed, dressed in a white shroud and placed in a coffin.

- Whenever possible, burial should take place within 24 hours.

- No flowers or music are provided, ensuring that there is no discrimination between rich and poor.

- Mourners ritually cut a slit in their outer clothes as a sign of grief.

- There are seven days of intensive mourning during which close relatives say prayers throughout the day, and neighbours and friends visit to offer condolences and help.

- For the following eleven months the Kaddish is said every day.

- Every year on the anniversary of the death, the family say the Kaddish and burn a candle for 24 hours.

MUSLIM BURIAL CUSTOMS AND RITES

There are approximately two million people in the UK who are of the Muslim faith. This group is composed mostly of families originating from the Asian sub-continent. There is also a sizeable number from the Middle East, Africa, and Turkey, Asian languages and Arabic are spoken at home, though English is perhaps the most widely used and understood among them all.

The Islamic concept of death is quite simple , the idea being that “from God (Allah) we have emerged and to God we return.” Consequently, the official mourning period tends to be relatively short, usually not more that three days. Widows mourn for a year in the Middle East and North Africa. The next of kin mourn for forty days, however this does not include the deceased’s spouse or children.

When death is imminent, the person is asked to declare their faith by repeating the simple formula: “God is One and Muhammad is His Prophet”.

The Imam (prayer leader at the mosque) is informed as soon as possible after death and prayers from the Qur’an (Koran) are recited over the body.

The body is then taken to the Funeral Director’s premises where it is washed by family members of the same gender as the deceased. This ritual is usually performed in a room that has been purified and from which all statues and religious symbols have been removed; special arrangements can be made with the Funeral Director to ensure that these beliefs, fundamental to the Islamic faith, are respected. After the body has been washed, it is swathed in a simple white cotton sheet or shroud; all Muslims are dressed alike to symbolise their equality before God. The body is then placed in a unlined coffin.

According to Islamic religious traditions, the prescribed mode of disposal of the body is burial. The burial of the body should take place before noon. If a person dies in the afternoon or during the night, they are buried the next morning before noon. If they die midday or thereabouts, then they are most likely to buried the next morning, as burying after sunset is not customary. However, in Britain delays are inevitable, as there are various legal formalities that have to be completed before a certificate for disposal is given by the Registrar of Births and Deaths. Nevertheless, custom prescribes that the burial should take place with the minimum delay.

The usual practice is for the deceased to be taken to the mosque, where special prayers are recited, before proceeding to the graveyard. A brief prayer session is also held at the cemetery. The body is then buried in the grave with the head and right had side facing Makkah (i.e. south east in the UK).

On the first three days after the burial the official mourning takes place, where the Qur’an is recited throughout the day by a professional reciter or with the aid of audiotapes. On the 40th day, a remembrance ceremony is held in the mosque (for men) and at home (for women), where a meal is shared in the evening. Women come to visit the family of the deceased and to share in the remembrance day. The next of kin, especially the first next of kin, wear black for the first forty days. The wife and adult daughters of the deceased wear black for a year in the Middle East, except Saudi Arabia where they wear white for the first three to five days only.

In addition to the specific rituals described above, the dead are commemorated in various ways. On Thursday evenings, prayers are offered to the dead after the magrib namaz, the prayers recited at sunset. Similarly, after Eid at the mosque, the family visits the cemetery and offers prayers for the dead. It is customary for Muslims to visit families that have been bereaved to offer condolences in the course of the year.

Summary

- Muslims believe that there is one God, Allah.

- Muhammad (peace be upon him) is the prophet of God.

- There is only one life to be lived. There will be a day of judgement when each soul is judged according to their deeds on earth.

- Extravagant expressions of grief are against the will of Allah.

- Mourning is demonstrated by readings from the Qur’an (Koran).

- The burial should take place before noon, and with the minimum of delay.

- The body is washed and wrapped in a simple white cotton sheet or shroud. All Muslims are dressed alike to symbolise their equality before God.

- The body is buried with the head towards Makkah (south east in the UK).

- On the first days after the burial prayers are said at home of the deceased.

- After the Eid celebrations visits are made to the cemetery to say prayers at the family grave. This is a reminder that even in the middle of happy celebrations, life is temporary and that it is important to live correctly to ensure eternal life with Allah.

Sikh Cremation Customs and Rites

Most Sikhs living in the UK are of Punjabi origin. They have come here either directly from the Punjab or from former British colonies (e.g. those in East Africa or South East Asia) to which members of their family had previously migrated. The first gurdwara (Sikh place of worship) in the UK was established in Putney in 1911. The Sikh population in the UK is the largest community outside India, that in the West London area being the largest within the UK.

Sikhs believe that birth into the faith is a result of good ‘karma’. Death is the door to union with God.

The cremation is a family occasion attended, as far as possible, by the close relatives of the deceased and friends.

Prior to the funeral the body is washed and clothed by the members of the family. The dead person is attired with the symbols of the faith know as the 5K’s – Kesh (uncut hair), Kanga (comb), Kara (steel bangle), Kachs (shorts) and Kirpan (short sword) – and the turban for a man and sometimes a women. On a route to the crematorium the deceased is taken to the gurdwara where a rumalla is placed on top of the shroud. At the crematorium, prayers (Sohilla and Ardas) are said. The button is then pressed by a close male relative, usually the eldest son of the deceased. The next day, the ashes are collected and then – in both India and Britain – taken to a designated area of running water and immersed. In Britain, after the funeral, the mourners go back to the gurdwara and wash their faces and hands. In India, for reasons of personal hygiene the mourners bathe after the body has been cremated on the funeral pyre.

Beginning on the day of the death, adult relatives, or if they are unable to do so grathis from the gurdwara (people who perform readings), usually take part in a complete reading of the Guru Granth Sahib (the Sikh holy book) at the home of the deceased or at the gurdwara. This reading is usually spaced over a period of ten days, and close family members, including children, would usually be expected to be present throughout. At the completion of the reading, a passage from the Guru Granth Sahib about belief and practices regarding death is read, followed by kirtan (songs in praise of God); the prayer Ardas is then said, followed by the sharing of karah parshad (specially blessed sweet pudding) and the eating of langar (a communal meal). If the deceased was the head of the family, the oldest son is given a turban to symbolise the taking of responsibility for the family.

Summary

- Sikhs believe that death is welcomed as opening the door to the complete union with God.

- The body is washed and clothed by members of the family and attired with the symbols of the faith. The body is then wrapped in a plain white sheet or shroud, and a rumalla placed on top.

- The body will be cremated and the ashes will be immersed in running water at a designated area. Sikhs in the UK sometimes take the deceased person’s ashes back to India.

- Both male and female relatives attend the cremation. They then return to the gurdwara or home of the deceased to read the Guru Granth Sahib. At the end of the reading, and after kirtan, Ardas is said, followed by the sharing of the karah parshad and langar.