Gardens of Empty Nothing – The Zen Garden by Ven. Mujyo Williams

Gardens of Empty Nothing – The Zen Garden

By

Ven. Mujyo Williams

Jizo-an Zen Centre Perth, Australia

Through this paper I hope to talk about the important relationship that gardens and the arts have to Buddhism and in fact the broader Mahayana context, but of course I will concentrate somewhat more on Zen Buddhism. The relationship of the garden to painting and architecture and how the garden and other elements help to highlight our relationship to ourselves, our inner eye, what in Zen is called Hosshin - Buddha Mind.

Besides references listed the comments here are also based on conversations with teachers, gardeners and my own travel experiences and observations in Japan and my experience making gardens in temples. I will offer some of my own thoughts on the transmission of Arts in the Zen school that may be of use in the future transmission of Zen in Australia.

The Zen Garden

Zen gardens are of course famous, but what is a Zen garden? First let’s ask, is there in fact any such thing as a Zen garden? As a gardener, my response is no, there is only the tree, the stones and the dirt. A garden has no label, from that stand point the gardens of Nanzen-ji, Versailles, or the common street house are no different. As a designer my response is that the gardens of a Zen temple are in fact arranged differently to the gardens of Jodo and Shingon and Nichiren temples, and of course differently to the gardens of Baroque Europe or suburban Australia or Japan. And as a Buddhist monk I have to say there Is and there is Not!

The future of the 21st century looks towards finding better ways to live with nature. In order to live with nature we must live with ourselves. If we do not do this then all our efforts to live with nature will fail. The appearance of humans on the landscape some 1.7 million years ago represented a milestone in nature. An animal appeared in the ecology who could develop the means to overcome any other and deliberately manipulate the environment and attempt to create a world for itself outside of ecology. Of course living in contemporary times we find ourselves with the possibility, if not reality, in which that ego endeavour has failed and threatens us with extinction in a way that the lion could not.

The need for shade under the tree is not unique, and it extends to the utilitarian cutting down of that very same tree, yet no other animal nurtures a tree simply for the pleasure of its growing, no other animal rests not only under the tree for shade but at distance to enjoy its appearance or symbolism. For whatever reason while cause and causality was selecting the traits that would become human, our hands that cut the tree also plant the tree, eyes that chooses it for cutting, appreciate its beauty, ears that listen to its fall also listen to the breeze through its leaves, cognitive abilities that make sense of all these things give us the ability to cut down a forest give us the ability to create and appreciate a garden. Faced with the challenges ahead, no less than our ancestors of the Rift Valley, our ability to appreciate the blade of grass under our very feet represents a vital role in our future survival.

‘Here this very blade of grass is a temple’- says the Tathagata Buddha

The garden is our humanity, our very expression of Buddhanature, that which cannot be expressed but just is, and is not.

Buddhism is perhaps unique among the Worlds Universal Religions in that it lacks a creation story to explain the contemporary world as seen by man, rather Buddhism places centrally the existential nature of the Universe, in fact multiple Universes as they relate not only to man but all things and non-things. Lacking an answer to how did we get here, Buddhism is not burdened by absolute position. This is important in the art forms that Buddhism inspires, in this way the Dry Garden of raked gravel and the Mandala, and the words painted onto a paper are connected expressions of what cannot be expressed. A single stone in a rippling sea of sand. A sea of possibilities.

The Wind Pine

Shoin no bunka, the ‘culture of the wind pine’. Shoin culture is synonymous with the Pen and the Window. The image of ‘craggy mountains and gnarled trees’ in the Mustard Seed Manual of Painting, with its hermit sage in a mountain hut, evokes the mood of Shoin imagery. In fact evokes the Shoin ideal of Heaven, Man and Nature as one. Shoin culture is counter to the distinction of brain and body as separate, the mind and physical, distinction of cause and consequence. In Shoin architecture the window does not separate us from nature, the view outside, instead it invites nature inside and diminishes separation. Shoin culture not only invites man to integrate mind and body, but see that they were never separate in the first place, that it is only distinction in our own minds. And Zen is sometimes known as the school of the Buddha Mind.

Zen crossed from India to China, the tradition holds that Bodhidharma an Indian monk took a boat from India and made his way across to China and finally settled in a cave in the Shaolin Mountains. Shaolin today is a complex of conventional temple buildings, but in Bodhidharma’s time the monks lived in the sandstone caves. There they practiced we understand a more Indian form of Buddhism philosophical contemplative Buddhism, various forms of meditation such as Samatha and Vippasana. According to tradition Bodhidharma finds the practice the monks in Shaolin and other too philosophical, and intellectual, instead he introduces a practice weighted heavily in favour of meditation and the cultivation of No-thought.

Huike goes to Bodhidharma pleading to be taught the Mind school, he says his Mind is sick and needs a cure, Bodhidharma simply says “show me your mind and I will cure it”. Where do you find something that is not separate from you? How do you ‘cure’ this? The question is its own answer, from a Zen point of view do we really understand the question? We cannot separate out the Mind anymore than we can pluck our head from our shoulders. In the garden this is simply the relationship of the Pen desk to the view inside and out. Bodhidharma the person is probably a construct, a representation of the many Indian and Chinese monks of the time, a representation of a new wave of Buddhist thinking into China. Seldom do people simply listen to and follow some strange looking person from a foreign land, rather Bodhidharma represents a movement, these stories and others about Bodhidharma and his successors tell us however about the development of Buddhism in China.

Some Six generations after Bodhidharma the Chinese monk Huineng establishes the doctrine of sudden enlightenment. Again representational of the fusion of Indian and Chinese thought. In fact most probably these events are reflections of the gradual development by many of a fusion of Chinese anti-intellectualism with Indian contemplation. Mahayana ideals began with the Indian Buddha Ancestor Nargajuna, but through these developments in China, Mahayana would fully flower, and the Zen school and others emerged at the beginning of this. In some ways Shoin cultural imagery and lifestyle practices are a representation of this.

From the T’ang dynasty forward, an explosion of Mahayana practice took place, it’s likely that up until that point Buddhism in China was marginal alongside native Confucianism and Taoism. What need in the land of Confucian Law and Tao would there be for Indian Buddhist intellectual abstraction? While other social causes in China would intervene, in the mountains of Shaolin the ‘Three Old Men’ would come together and Buddhism would do what Buddhism does very well, adapt. Buddhism is not a religion of the Absolute, rather it teaches the temporal nature of things and ideas, of even Buddhism itself. It is use that turns the stone in the monkey’s hand into a tool. The truth of Buddhism and its ‘proof’ if there were any need of it is that nothing is absolute, that nothings ‘Is’, and adaption is the consequence of that .

The non-Buddhist Sage Confucius says, “Seek not a world with more laws, but a world with fewer lawyers”. This intuitive character of rightness naturally emerging in a healthy society. A very relevant warning in a world today which is making violence an industry from fear and control.

Shoin culture is more than a nostalgia for beautiful days gone by, bearded sages and delicate tea. Shoin culture is the appreciation of the tree alongside its clever use.

Therefore with it’s down to earth style – even in expensive terms, for Shoin style can be an exercise in the wealth to demonstrate tasteful poverty, reacted against and replaced opulent courtly Shinden style in Japan in particular and today Shoin style has come to be defining of the Japanese house and interior/exterior sensibility.

The Zen Temple

To understand the garden we must understand that the garden is not simply put there, it does not exist as a separate or detached unit of space in a Zen temple, or in Shoin style; rather the garden plays various vital roles in mood and function. From the setting of a ritual procession in the ritual life of a temple, to the relief of atmospheric conditions at an architectural level. First we’ll summarise the layout of a large temple and a sub-temple and then discuss some examples of these and how the gardens and other elements function.

A large Temple complex in the Zen school, will comprise a Zen Hall called a Zendo, an Administration building known as a Kuri, often a Hondo or Buddha Hall for services, a main gate or Senmon which is a ceremonial building in itself where ritual observances are often carried out. These main buildings maybe in everyday functional use, or perhaps on occasions. A Senmon dojo complex will adjoin this main one, in the style of a sub temple with a smaller Zendo functioning daily as a place for training monks or nuns to live and practice Zazen in seclusion. The Senmon dojo will often be a fairly secreted hidden place of which the general public would be oblivious. The arrangement of the Gate, its boulevard of pines, leading to the Zendo and Hondo maybe said to be a hangover from Shinden courtly architecture.

Other auxiliary buildings may be present also such as, a Treasure Hall, various small sub buildings dedicated to various Bodhisattva e.g. Kannondo, and often in Zen temples a Shakyodo for the purposes of Sutra copying and storage.

A smaller complex whether an attached sub temple or a detached one will often consist only of a Hondo and Kuri, a simple gate, and priest’s residence. Daily private observances will be held here by the priest in residence, and possibly the Hondo will double as a Zendo for a local lay meditation group.

The Archetypal Zen temple complex is laid out to represent Man the head, body, arms and legs as five main building groups. Tofuku-ji in Kyoto is regarded as the finest example of this in the Japanese Rinzai sect. Tofuku-ji was the first Zen Temple in Japan built specifically as a Zen Temple, there are older Zen Temples, such as Kennin-ji in the Gion district of Kyoto. However those are temples originally belonging to other schools, or villas of feudal Emperors and Lords converted over to use. The gardens of a major complex reflect those groupings typically Chinese Black pines are planted in connection with the spiritual origin of all Zen temples, Shaolin Temple of Song Mountain in China. Even in the smallest temple in Zen a single pine tree is considered an essential reminder of that connection.

Surprising to some, the famous dry gardens associated in popular mind with Zen temples are not a main feature in main temples. Instead groves of Pine take the place of the groves of tropical trees associated with the Indian sub-continent. The tree is central. The Pine tree in Zen representing ‘this life’, practical and evergreen, the blossom in the esoteric sects ‘representing the’ transient’. In some temples especially those in outlaying areas in a city such as Kyoto the mountain maples of Higashiyama or Arashiyama play an important role in the background of many temples. The maple leaf, the wisteria flower, the evergreen pine needle are a contrast of paradox, the ever changing and the everlasting, the floating world and the world of the everlasting now.

It has been speculated that early Buddhism evolved out of tree worship, in India, and the connection with the Bodhigara or Tree temple that predates Buddhism. Certainly the tree as a Buddhist motif is there from the beginning, the Bodhi tree that Shakyamuni sits under, for example. It seems not too much of leap that tree worship plays a role in the evolution of Early Indian Buddhism, the same way elements of Pantheonistic religions added to Christianity. The Bodhi tree does not appear as a symbol in Buddhism by accident, Buddhism is eclectic and has absorbed and adapted much of what has gone before it, and which it has lived beside. In the mountain of Northern China where there are no native Bodhi trees, the mountain pine replaced it. In the mountain of China the pine tree took on special symbolism as the flavour of mountain life.

In the compounds of the smaller sub-temples are generally located the gardens we typically associate as ‘Zen gardens’. The sub-temple is normally a Shoin style building complex and the popularity in Japan of Shoin architecture from the end of the Momoyama period parallels closely the appearance of ‘Zen garden’.

In front of the main gate of a main temple in Japan, a representative river or lake is situated with a bridge leading up to the main gate. Usually this ‘river’ or lake pond is man-made and will often contain lotus plants and in some larger cases a Crane island and a Turtle island. The Main gate and bridge crossing features in the installation ceremony of a Chief Abbot in a main complex. The Abbot literally as in the Heart Sutra or Prajna Parramitta Sutra, crosses to the other shore, there installed as the living Bodhisattva of the temple to lead others equally to awaken their true nature.

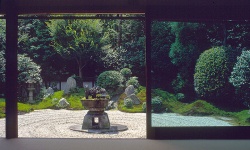

Walking further into a Zen temple we may meet a moss garden or a dry garden (Karesansui – Empty stone and water). This garden is usually found within a private compound. Today many Japanese temples are divided up and reduced in size. A main compound with Buddha hall, in the case of a Zen temple a Dai-Zendo or great meditation hall, and others is surrounded by other sub temples where various administrative duties go on or are the residences of senior administrative monks and priests.

Formerly most often the main garden space was used in fact for ritual purposes, such as the installation of its abbot monk. Recently, many of these courtyards have been converted into gardens.

Not all Temples in Japan are purpose built, it’s worth noting also that in Zen there is a long tradition of converting buildings from other uses. Therefore a temple like Nanzen-ji, Tenryu-ji, and Daitoku-ji in Kyoto, are also main temples or Kyoto Gozan ‘Five Mountain’ converted Imperial Villa complexes. Others are converted from other schools of Buddhism.

Tenryu-ji’s main gardens are based around a small lake of water viewable from many vantage points over the complex. However the garden was constructed by the Zen monk Muso Soseki and, though it is a true lake garden with waterfall, it follows the same design principles as many Dry gardens we more typically associate with Zen. At these converted temple complexes other elements such as a Senmon gate, sub-temples, and Senmon dojo sub-complex, may have been added, as in the case at Tenryu-ji and Nanzen-ji.

From all points of view, Symbolism and function play an equal role in the temple garden. A typical sub-temple of any tradition has an entrance garden, beyond its main gate, and an inner garden. The path leads to another world, as it does so the Mind is nurtured as are the living plants and animals. The reception entrance to the temple will lead into a formal drawing room, as one enters on the opposite of the drawing room the visitor is met with a garden vista, leaving one world to another world beyond. A typical example of this found at Komyoin sub-temple, Tofuku-ji in Kyoto. Typically the Hondo rooms will have their own garden, and smaller gardens will fill voids on the opposite side of the complex that lead to the kitchen and other auxiliary buildings.

Korean and Chinese temples follow similar lines with some variation.

Emerging Western Zen Temples are usually converted residences and in some cases converted Christian Church halls. The gardens at these training centres are often hybrids of Japanese temple styles and western residential. A few newly built temple complexes also exist mostly those existing as branch organizations from China, though a branch temple from Myoshi-ji has been constructed along Japanese lines in Honolulu U.S.A

Jizoan Zen Centre is a converted Australian 1960’s residence and follows the pattern of a Japanese sub-temple, with a medium sized Karesansui in the North garden, a garden representing a dry waterfall in the West parallel to the future main gate is currently under construction, and an Eastern water garden. The Western garden at Jizoan will eventually provide a scenic appreciation on arrival and leaving of a mountain scene, backed by deciduous blue flowering Jacaranda tree mimosifolia, endemic to Perth. While the Karesansui is visible from the Zendo and provides a study for zazen in the summer evenings, the water garden with its trickling flow provides somewhere to dispense the meal offering to the Hungry Ghosts (Korean Paradise fish Macropodus opercularis). During daily zazen sessions at Jizoan like many other Zen temples Kinhin walking is taken through the gardens at intervals, so the gardens not only exist aesthetically as settings to, but also function in the training.

No doubt as time goes on a Western Zen temple garden will emerge, certainly the onus on any garden designer is not to merely transplant or replicate a scene or style but to adapt it to every circumstance. The gardens of the Kamakura temples are not the same as gardens in Kyoto temples. In Australia the light is bright and the air dry. In the United States similar contrasting conditions exist, making no Zen garden constructed outside of Japan a ‘Japanese’ garden, anymore than a garden constructed in the Chinese or Korean styles could be.

Five Periods of the Garden

Japanese Zen Temple gardens are generally considered to fall into four periods of style or design, Hien, Kamakura, Muromachi, Edo and Modern (post Meiji era) corresponding to those socio-political eras in Japan. Styling is not always representative of when the garden was made, a contemporary garden, and many are, might be constructed in the Kamakura style for example. But here is a summary of the styles and periods of fashion.

Hien era is associated with Shinden architecture, a courtly style, and the gardens of that era are decorative in style as are the buildings, in the Hien era indoor and outdoor gardens already existed but it is in later periods that the garden especially the indoor of courtyard garden takes shape as we know it.

The gardens attributed to the Kamakura era (1185-1333) are picturesque in design, also they are often characterized by bridges and moss and stone islands, contrasting sand or water, gardens of this style may represent a transition from the courtly stroll garden. The design elements that were long established in the stroll garden often appear miniaturized in the courtyard gardens that appear from this period onward. Kamakura gardens often consist of large concentrations of plantings of miniature trees and shrubs and sandy streams, sometimes water streams. The end of the Kamakura period and the beginning of the following Muromachi period reflect the relationship between then Japan and Sung China.

The gardens of the Muromachi (early 1300’s to the late 1500’s) are a development onward in parallel to the influx of Sung Chinese Learning. If Muromachi gardens are flamboyant, Muromachi gardens are toned down, and sedate, perhaps reflecting the mood of the times, since this is a period when Japan fell into a state of almost constant civil war. Muromachi gardens feel more secretive. It’s during this period that the great Priest gardeners called Soseki, literally ‘Stone carrying monks’ are most active. Muso Soseki (1275-1351), or Muso Kukushi as he is also known, is arguably the Michelangelo of Japan in his Artistic accomplishments in the world of painting and garden design. He and Soami, who was active at the end of the era, are perhaps the most prominent of this time. Muso Soseki is often claimed to have designed or re-established more than a thousand gardens. Certainly often walking on Arashiyama and other parts it is nearly too common to come along a temple gate and a garden stone claiming Muso Soseki made this. It might be pointed out that in some cases as abbot of Myoshi-ji toward the later part of his career, in some cases Muso Sosekis involvement in some gardens may have been no more than to approve their plans, or raise the funds, he may have simply played the role in some cases of a producer though of course he probably did build many important projects. Soamis gardens maybe said to transition from Muromachi style to Edo. Ryoan-ji is often cited as the first true dry Zen garden, Karesansui, which would become so important as a style of construction in the Edo era. Edo period gardens, post 1615, reflect the conservative taste of the post renaissance peace. The Edo period in Japan is a time of political consolidation and civil restructuring, the gardens of this period reflect that conservative hope. Also gardens of this period show the artistic styles we truly think of as Zen gardens, or distinctly Japanese in style. The stones and plantings used are generally larger than those of previous eras and the arrangements less complex. Late Edo cultural disciplines may be said however may be said to show signs of creative stagnation, and garden design undoubtedly does not escape this, as design falls into conservative reproduction of previous and current eras. Larger stones are used, but arrangements become sparser. We may recognize an Edo period garden by its sparse landscape and elements, larger stones and larger trees.

Finally at the beginning of the twentieth century after a period of decline following the collapse of Edo society and the restoration of Imperial authority a new wave appears led by the modern designer Shigemori Mirei (1896-1975). The new gardens use large stones building on established Edo taste, but however employ sometimes new materials in previously unconceived ways. The gardens of Tofuku-ji and a number of its sub-temples are among the first in this new wave of restoration. Mireis’ gardens restored the art form to the contemporary. Prior to him, while many genius garden designs continued to be made, they were increasingly becoming a formality. Mirei restored the garden to contemporary art. As art objects they stand alongside that of the other great modernists. The architectural garden as it is known in contemporary Architectural design. Mireis’ pioneers the use of Concrete as a feature material, previously only used to set stone paths etc. He also took geometry in his designs to a new level not previously present. His gardens reflect the meeting of old and new in a fusion of creative revolution. Mirei transcends stereotypes and yet his gardens help define Japanese design, yet they have a life beyond Japan. Modern style gardens which Mirei pioneers are most easily distinguishable from the previous Edo era by their dynamism. Large stones, few plantings, dynamic tension in the space. Preceding era’s seem by contrast to represent cultural refinement, or quietude. The gardens of the modern era combine these feelings and add a sense of present to them. Mitsuaki Mirei the son of Shigemori, describes his fathers’ work as the creation of ‘timeless gardens’ not seemingly to belong to an era of the past and which he feels sure will continue that feeling in the future.

The 20th century gardens of Tofuku-ji compared with the 18th century gardens of Nanzen-ji designed and constructed by Enshu in the Edo era, yet they are distinguishably modern in way that Picasso and the Cubists are different from Monet and the impressionists. They connect not only with the world of Chinese painting which is the basis of Japanese garden aesthetic but also with contemporary Western painting and sculpture. They bring the garden back into its place among contemporary sculptural art forms.

The Zen garden and modernism

Shigemori Mirei was not a monk, most garden designers today are not, and unlike in Muso Sosekis day, most contemporary Zen monks and nuns know nothing about garden design and even less about how to build them. Mirei was a self-taught designer who first commission was the construction of the gardens at Tofukuji. The main garden of the Abbot’s precinct features giant stones laid into what had once been a ritual courtyard. Another garden reuses stone paving in a checkerboard, another fades from gravel to another checkerboard arrangement of azaleas. The general theme of all of the abbot’s gardens is that of the rice field. Appropriate because the abbots’ great surplice is traditionally patterned in that of the rice field, well actually it represents a poor man’s cloth, but the Chinese ancestors also noticed the resemblance to the patchwork of a valley. Reflecting that the ‘True man of no Rank’ plays with emperors, but is still a simple farmer at heart.

Through this overt use of abstract symbolism in his garden design Mirei connects the modern Zen garden with the gardens of earlier times. The gardens of Tofuku-ji in that sense are everyway equal to the gardens of Tenryu-ji even though they superficially appear worlds apart and separated by nearly 800 years.

The modern Zen garden does not belong solely to Japanese designers any longer as the work of Marc Peter Keane demonstrates. Keane is a leading architect and garden designer in a wave of new generation designers working in Japan and the West. Keane’s work spans traditional tea gardens in Kyoto to contemporary works such as Tiger Glen garden at the Johnson Museum, New York. Keane’s garden there is modelled on a traditional story of three Sages from Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism, in the classical manner, yet there is little classical about the result. The dry stream of the Karesansui style garden truly appears to rush under a bridge through the gorge.

Painted Gardens

The relationship between painting and gardening cannot be overstated, it’s no accident that Soami, Muso Soseki and even Mirei are considered master visual artists in their own right.

The garden is a painting. In the room of the window we find a painting of a landscape on the wall and turning, another landscape has entered through the window. Where did one end and one begin? Painting in design terms is the source of the garden, and for the painter the garden is the source of painting. The garden is a Three dimensional living sculpture of a landscape, the painting a Two dimensional one.

A stone accented by a burst of grass or a flowering camellia, a little to the right a gentle bridge formed from three natural stones crossing a dry stream bed. Which came first the garden or the painting? So close is the relationship that the garden can be said to be a living sculptural representation of a landscape painting. Even an abstract setting like the famous dry garden at Ryoan-ji, the second most visited place in Japan after the Golden Pavilion at Ginkaku-ji. Soami when he was designing Ryoan-ji garden was versed in the art of landscape painting, in fact, like Muso Soseki, he is one of the great painters, as well as garden architect. So close a relationship to visual art, the art of gardens begins with the classical ‘Mustard Seed Manual’ and others, on which Artists of Chinese painting study.

The landscape garden designer must study natural landscapes, established old and new gardens and try to become at least competent in two dimensional works as well. To sit down with a pen and paper and make notes on the random occurrences in nature for the designer is not to replicate, but to discover the nature of feeling that stone or stream imbues. A garden or a painting in this sense should not be a photograph but instead create feeling of places we once walked in or might hope to in the future. Intuitive understanding of the place is paramount.

Through painting and sketching nature and gardens that have gone before the eye for design is trained. The Zen garden as mentioned before is not strictly a natural garden though it is a garden of this world too. This eye comes of observing and coming to a close visual relationship with the stones and plants, as well as a desire to deepen the inner eye through that external observation.

There are Formulas, such as in the Sakuteiki a garden manual teaching standard design formulae, and of course this kind of specialized garden design is usually learnt in an apprenticeship. The Sakuteiki manual dates from the Kamakura era. Such manuals contain drawings of garden vistas and elements such as standard stone grouping types. A designer will consider what purpose the garden is for? A house, an office, a Buddhist temple – which school? A shrine or a park etc. In the case of temple gardens certain Buddhist motifs are possible. The triad of Sakyamuni Buddha and the Bodhisattvas of Wisdom and compassion flanking the ‘Buddha stone’ for example. Such a grouping however will not usually appear obvious, the triad will be among other balancing stones and the character and selection of the stones themselves. A standard arrangement might include a ‘Tiger or Dragon mountain’, ‘Turtle and Crane’ islands, a triad, or a grouping or individual stone representing some principle, even the arrangement of moss in contrast to the gravel. These hidden motifs in complete view to all who can see, are the same motifs found in Chinese paintings.

Taking the placement of islands in contrast to each other, in a Karesansui the islands may not appear obviously islands to us. Taken out of water or even isolated to a rectangular featureless sandy compound the crane and turtle islands may no longer be, but their design tension remains. The triad of stones hidden by a stream does not preach about Buddhist doctrine aloud to us but through the tension and harmony of three stones placed in triangular composition and located some appropriate distance from another solitary stone, we are informed subliminally of infinite nature, “Not-Three Not One”, of existence. The ants and the silence preaches all we need to hear, it is left for us to intuitively appreciate it.

Each stone and plant and grouping is distanced out in opposition and tension and harmony to others within the garden. Stones seem to float or have weight accordingly, the Tiger seems as though about to pounce or the Dragon reclines above the ocean on a cloud. Empty spaces and whirling sands like the ebb and flow and stillness of Karmic relation. Real but never absolute, ever changing or at least from focal point to focal point.

A modern day garden at Empuku-ji represents the principle of Compassion, the moss island in the middle of the sand spells out the character for Mind, a tall Stone represents the Bodhisattva Kannon herself, and various other stones represent words from the Sutra of Compassion ‘Kannon Gyo’. All appears to be a natural abstract beautiful aesthetic yet meaningful.

Keane’s Tiger Glen garden design, and Muso Sosekis Garden at Tenryu-ji and others draw directly from standard themes of painting and literature, sometimes from secular stories and scenic musings to teachings in Buddhist scripture. Whether the garden is the fancy of a courtly villa, a sub-temple or the atrium of a modern museum, the skill in a garden design just like any other art form sometimes is not in the invention of a new story, but the original interpretation of an old one.

The Zen garden – contemplating dragons

Shoin culture may have incubated in temples and then the sensibility spread to court life. It’s certain that the water stroll garden came first, the original form originating in China, and spreading to other Mahayana countries. The temple garden probably didn’t originate in temples at all but in Court, then as temples became more and more civil buildings the garden must have made its way. In China a civil servant often retired to temple life at the end of his years, this may have contributed to the taste for it, combined with Mahayana temple rules encouraging work for monks. Idle hands are idle minds could have been a Zen maxim.

Distinct styles are to be found in Korea, Vietnam and Japan and of course recently in Western countries also a new adaptation of the Stroll garden is emerging. These stroll gardens were usually constructed for the pleasure of the court, later as villas were given over to become temples the design of stroll gardens began to change. Not just the fancy of noblemen, the stroll garden became a backdrop to spiritual contemplation and creative activities.

Later these principles began to be applied to gardens beyond the pond. Among the earliest of these transitional gardens is again to be found at Saiho-ji famously known as the ‘Moss Temple’. Saiho-ji still has a lake, artificially constructed by diverting part of the passing river, but it is a far more abstract garden than that of Tenryu-ji. In fact Saiho-ji started off as a temple of the Jodo sect, the garden still reflects another-world ethereal quality of the school of ethereal wisdom, yet its restorer, the Rinzai Zen master Muso Soseki added a Zen component by shaping the islands of the Moss garden into the character for Heart ‘Kokoro’, Heart - Mind which is central to both schools of Buddhism yet expressed in a way that would mark out Zen gardens, a certain artificial naturalness of this world, rather than of ‘other’ world.

Another garden connected to Muso Soseki is the garden at Tenryu-ji in the Kyoto district of Kita Arashiyama. Tenryu-ji began life as an Imperial Villa, later it was donated to the Rinzai School to help it establish in Japan, it is a working temple of the Rinzai School and one of the Five Mountains, or Head Temples. The garden was restored and redesigned by Muso and is widely regarded as one of the most perfect examples of a classical Stroll garden, a large central lake dominates fed by a waterfall, and yet it definably a Zen garden. In the autumn and the spring the mountain landscape becomes full of colour and clouds swirl above us. Just a few Kilometres away in the same district of Arashiyama is the Shingon school complex of Daikuku-ji, also a converted Villa yet comparing the two water gardens the garden at Daikuku-ji, is not a Zen garden, speaks another message. Daikuku-jis gardens are planted with willow and blossoms, the lake is an ethereal gateway to another world. It is pleasant yet other worldly, in contrast to the lake garden at Tenryu-ji which while pleasant has a tension in the design, a place where a dragon might reside in this world. Tenryu-ji is the ‘temple of the heavenly dragon’ and its appearance certainly lives up to it. Even building lay out reminds one of some great dragon sleeping by the lake, we could almost imagine the buildings to resume their true form in the evenings and disappear across the lake and up its distant waterfall until next morning. The Temple of the dragon? Or is the temple the Dragon? We look out across the landscape and feel the presence at our back. What a place for Rinzai training.

The main indoor garden at Roan-ji is probably the most famous Zen garden in the world with its flat rectangular courtyard, and solitary looking stones. Ask anyone in the world to describe a Zen garden and they most likely will describe the garden at Ryoan-ji. It seems a world away from the lake stroll garden of Tenryu-ji, however its design formula is exactly the same, following exactly the same design principles as a landscape painting. At first it would seem the two gardens could not be any more different. Soamis’ masterpiece at Ryoan-ji Zen temple in another part of Kyoto, the iconographic arrangement of stones in a featureless gravel courtyard. Simply the scene is reduced to a number of stone settings on a seemingly featureless flat plane of white gravel. At Ryoan-ji, Soami created the archetypal dry garden as we think of a Zen garden to be. While the garden at Tenryu-ji is an expansive wet stroll garden. Yet both the Muso Soseki and Soami span an inner silence that is perhaps the most definable feature of a Zen style garden.

What both gardens share is the horizontal visual plane. At both Tenryu-ji and Ryoan-ji and many other Zen Temples gardens are designed on the Horizontal visual plane of Single depth perspective. This plane is similar to viewing a landscape painting in panorama. The effect is calming and simplifying as the eye is taken across the landscape rather than through it, the viewers’ eyes don’t jump about or refocus the view is simply taken in, releasing the mind to consider more important things. They are both contemplative to look at even though each are constructed from very different materials. Show a person two pictures one of a path disappearing up a mountain another on a flat horizontal plane and the second is most likely to be preferred, because the flat horizontal plane is more calming, the cornea of the eye makes fewer adjustments to focus and the visual information is therefore processed more quickly and economically.

The garden of Ryoan-ji just ‘Is This’, at Tenryu-ji we listen to the Cranes scream and the water trickle invoking the sound of the Shakuhachi flute, we feel the tension of the dragon. Ryoan-ji might be the Dragon’s other abode, but there the scene laid out before us is altogether different. Perhaps this is the mountain peaks as seen by the dragon as it flies above the clouds?

The depth of the lake

Is not in its fathoms

But in its dragons.

The height of the mountain

Is not in its peaks

But its people

The dragon is a recurrent theme in Rinzai iconography. Rinzai talks of becoming the True man, the true Adult, the maturation of the eye. The dragon represents that maturation. There is a myth that if a Koi is strong enough to ascend a fast flowing waterfall it is reborn a dragon. This folk myth is a frequent analogy for the training of Zen. In the Hondo at Ryoan-ji are sliding doors depicting the cloud dragon and jewel of Wisdom. All around us in a Zen temple a recurrent reminders of the potential of man, often through the relationship with nature. And yet Man does not exist. We are but part of a stream of Karmic consciousness, not separate of that, our thoughts our actions

The Dry Garden - Bridges across empty nothing

Sitting in front of the Dry garden at Ryoan-ji we well ask, What does it mean? Unfortunately, tourists are often distracted from this question by the challenge that not all the stones are visible from one viewing point. The stones are arranged in 3,4,5,2 groupings on the dry raked empty white space. What does it mean? That is precisely the point. The endless question. For a Zen Buddhist it is common to be asked, “Have you had it? – Satori”, “Have you seen into it all?” That’s what you’re supposed to do right? Find the answer. Herein is the paradox of Zen, the paradox of asking. Like the raked lines in the gravel, “What does it mean?” nice problem. Far from the absolute creative death of knowing. Sitting by the garden asking, in questions we are free.

The Dry garden or as sometimes colloquially expressed – the garden of empty space, has two origins. The space as already said in large scale courtyards is often a converted space, once used for ritual and later made into a garden, second the need for spaces around the buildings to provide airflow. Today in modern buildings any space made available to aesthetics in anyway is usually a luxury, in the past it was not only a luxury but a necessity for cooling through hot summers. The many gardens intersecting detached buildings and walk ways play a vital role in environmental control.

As such in Japan gardens maybe classified into Outdoor and Indoor. Outdoor being mainly stroll gardens with large landscapes over 300 meters or so, in some cases ranging over kilometres. Indoor being medium to small gardens close to buildings often surrounded by walls or hedges and architecture. The courtyard garden at Ryoan-ji would be considered an indoor garden by that standard, the stroll garden with pond beyond it an outdoor stroll garden.

In both cases most people would be surprised to learn that the same design principles and even the same design manuals as 2 dimensional paintings are used. A garden of either the courtly outdoor type, which might include stones trees and birds or the abstract indoor type of nothing but raked gravel, are both Chinese landscape paintings in three dimensional rendering.

The gravel courtyard garden began life in temples as we said for utilitarian reasons, later the spaces were converted. Something in human nature compels even the most pragmatic of us to enjoy the intrusion of nature in most cases, certainly we can’t talk about a healthy mind as one which would see the world turned to concrete, and even on the balcony of an inner city ‘high-rise’ we inevitably find a pot plant, or even a pitied crevice weed left struggle on.

Today also we can consider that Zen style ‘Karesansui’ gardens are not always made for temples, and around the world many are constructed for homes and offices, and public places. Though if the design elements are removed from their function is it still truly what it is labelled? Maybe a Zen garden and a ‘Zen style’ garden are not always the same thing.

Temples of Tea

We cannot talk about the tradition of gardens in Zen without talking about the garden of the tea house. By tea house of course means the small semi-detached complex in which tea ceremony is held. One day in Kyoto I met some tourists who when I asked them where they had been, told me they had been visiting Tea temples. There are of course no such thing as tea temples, but I guess having compared the obvious seriousness of tea culture surrounding the little buildings that Tea ceremony is held in, and the Buddhist temples of Japan they thought this was another kind of Temple, it’s a natural enough assumption. Tea does seem to be worshiped in them. David Farrelly in the ‘Book of bamboo’ coins the phrase ‘Temples of Friendship’, which about sums up the intention of tea culture.

‘What is the secret of Tea? Asked a student of Sennen Ryukyu. “Oh to make everyone comfortable, to see to everyone’s needs and pleasant conversation’ he replied. “Just that?, it’s too easy”, “Well if you can do that easily, then I will become your student”. Tea ceremony is not exactly Zen, certainly not exclusive to it, though it began from Zen temples, the earliest Japanese Zen priest associated with tea is Daito Kukushi, the founder of Daitoku-ji Zen Temple in Kyoto, to this day the association between Daitoku-ji-den and Tea ceremony remains close. All tea schools trace themselves back to the temple and Daito’s introduction of Thick Tea (Matcha) along with Zen to Japan.

Bodhidharma also appears in the story of tea, supposedly having brought a Chrysanthemum seedling form India with him, another more poetic version has him ripping his eyelids of to sit stoically gazing at the cave wall at Shaolin where his eyelids fell and turned into tea leaves. Again both versions and others are highly symbolic of the role the stimulant plays in Zen practice and refined culture.

Certainly there is a traceable lineage in Japanese Zen Buddhism of Zen teachers who were also involved in the evolution of tea appreciation from an opulent exclusive officiado practice of the Imperial court to something which ‘common’ people might enjoy in the restricted taste of Zen. However the appreciation of Thick tea or ‘Cha no yu’ evolved as a primarily lay activity.

Certainly among the auxiliary rooms and buildings of a Zen Temple is a tea house or tea room, and all Zen monks have at least a small degree of knowledge of Cha no yu in some degree. But a Tea house or tea room is often found on the gardens or in the building of wealthy household today. Somewhat ironically since in modern Japan the only people wealthy enough, outside of a few spacious temples, can construct a detached tea house, itself a facsimile of a poor man’s hovel. But irony is the point, and Tea ceremony is ritualized Irony in order practice humility. And the various schools of tea have set up various complexes to practice their version at.

Secular Tea ceremony is taken to be founded by Sen no Rikyu in the 16th Century, certainly he and his immediate students popularized it beyond the temple. Sen no Rikyu was also an accomplished garden designer, as were many of his students and the world of tea has a close relationship to other arts. Of Sen no Rikyus’ immediate disciples, Kabori Enshu must be mentioned, Enshu founded his own school of Tea also, it is Enshu however more than anyone else who is said to have joined Tea to the garden. His designs for the Tea house placed even more emphasis on the garden, and Enshu is one of the great Secular Garden designers of Japan. Enshu is the designer of the garden Abbot’s garden at Nanzen-ji. Enshu is also credited with a style of ‘Zen’ like garden lantern.

The tea house or room has its own type of garden, the Chaniwa, there are various interpretations but in general the Chaniwa is designed to be naturalistic. The first secular founder of tea Sen no Rikyu laid out the first rules for a tea garden, simply that there were to be no rules other than that the garden should prepare the mood of the guests and hosts through its natural simplicity. A water basin to purify one’s self at the guest entrance, a place to sit and enjoy pleasant conversation until admitted into the tea room, a space to define the waiting reception room from the tea room itself. Untrimmed plants and trees, in contrast to the tightly shaped leaves of a temple garden. The tea gardens nearest relative is perhaps the gazebo garden of England or the Southern United States in function and mood, but reduced still further until almost nothing remains.

Perhaps like the Tea garden and the room of Tea, the practice of tea maybe perfect Buddhism, everything removed until nothing remains.

‘Won’t you please have a cup of tea?

Good day, Yes I will,

Etcetera, etcetera and a pleasant conversation,

Thank you goodbye

– Traditional Tea song

Conversation of Silence

The garden is not just a space filled with design features, the garden is a communication. Perhaps this is why over the 1.7 million years the monkey that came down from the trees, then picked up its seeds took them with him, planted and cultivated, then paused to admire and reflect upon the Oak tree in the garden.

It might seem a poetic image, but we, as a generation are uniquely placed to appreciate and understand the vastness of this achievement over the eons. If this is the communication age then it seems appropriate to pause and reflect on what we have done and the potential communication of so many billions of people on the planet today. The opportunity to share the common creative communication of Humanity. The Mandala, the Garden, Writing Script belong to us all. Created, developed and passed on by our common ancestors. The stream from the past to the future.

I once had a conversation in Japan with an expat Englishman, who complained that any society which finds itself needing to remind its people of manners through a poster on a train is somewhat fallen. I think maybe so, too, however that conversation about the type of society we should make should have happened before the train was ever invented to carry the poster. But perhaps through inventing the garden and the window we did have that conversation, and the garden is an ongoing reminder of that.

References

- David A Slawson, Secret Teachings of Japanese Gardens

- David Farrelly, The Book of Bamboo

- Tom Wright, Zen Gardens

- Shigemori Mirei, Shigemori Mitsuaki

- http://news.nationalgeographic.com.au/news/2013/11/131125-buddha-birth-nepal-archaeology-science-lumbini-religion-history/

- http://www.columbia.edu/itc/ealac/V3613/shoin/mainpage.htm

Source

Buddhism And Australia Conference 2015 http://buddhismandaustralia.com/