Gender, subjectivity and the Feminine Principle

early generation of Western studies of Tibet. When W. Y. Evans-Wentz edited the early translations of Tibetan tantric texts, he asked the Swiss psychiatrist to write psychological commentaries for two of the four works.1 Jung had been deeply influenced by exposure to these tantric texts, and it is clear from his writings that he "mined Asian texts (in translation) for raw materials"2 for his own theories. One wonders how much his views of the anima were shaped by his study of the

few translated Tibetan texts to which he had access. Throughout the Collected Works, he spoke of deities of Tibetan mandalas as symbolic expressions of the importance of the anima. But when describing the deities, he followed the example of

Arthur Avalon's translations, making little distinction between Hindu and Buddhist tantra, referring to the central deities as "Shiva and Shakti in embrace."3 In his commentary on the

Pardo Thbdrbl, in which he encountered dakinls of the pardo in wrathful forms, he called them "sinister," "demonic," "blood-drinking goddesses," in "mystic colors."4 Here he made no mention of the anima principle. Ironically, Jung would have denied for Tibetans a relationship between the dakinl and the anima, for he felt that the "Eastern view" was too introverted to

require it; and he suggested that the extraverted quality of the Western soul-complex required "an invisible, personal entity that apparently lives in a world very different from ours."5 Instead, he would have spoken of the dakinl as "psychic data,. . . 'nothing but' the collective unconscious."6 Jung's writings nevertheless set the stage for the tendency to psychologize and universalize the

interpretations of various tantric principles. Giuseppe Tucci applied Jung's ideas in elucidating the mandala, and Mircea Eliade drew on both of them for his work on the subject.7 The influence of the Jungian milieu was apparent in commentaries by Lama Govinda and John Blofeld.8 But the overt associations between the dakinl of

Tibet and the Jungian anima were not explicit until 1963, when Herbert Guenther identified the contrasexual dynamics of each. As Guenther commented on the appearance of the ugly hag to the scholar Naropa:

all that he had neglected and failed to develop was symbolically revealed to him as the vision of an old and ugly woman. She is old

because all that the female symbol stands for, the emotionally and passionately moving, is older than the cold rationality of the intellect which itself could not be if it were not supported by feelings and moods which it usually misconceives and misjudges. And she

is ugly, because that which she stands for has not been allowed to become alive or only in an undeveloped and distorted manner. Lastly she is a deity because all that is not incorporated in the conscious mental make-up of the individual and appears otherthan and more-than himself, is, traditionally, spoken of as the divine.9

In referencing this personal commentary on the dakinl appearance, Guenther remarked that "this aspect has a great similarity to what the Swiss psychologist C. G. Jung calls the anima." The notion that the dakinl, like the anima, represents all

that man is lacking and for which he yearns has pervaded Western scholarship since the early 1960s.10 Jung's anima is the image of the female in the individual male unconscious, shaped by individual men's unconscious

experiences of women early in life. These images are further nurtured by the much deeper archetypal collective unconscious. The anima represents the intuitive, nurturing, erotic, emotional aspects of psychic life often neglected in male development. For men, this contrasexual image is the gateway to the unconscious, in which real women, or dream or

symbolic images of women, lead him to the depths. Jung referred to the anima as "the image or archetype or deposit of all the experiences of man with woman,"11 placing the subjectivity of the experience firmly within the purview of the man. She

is the key to wholeness, through whom he is able to access the hidden parts of himself. Jung identified the anima with personal subjectivity, the inner life, which is the reverse of the public persona, in which one's private dreams, impulses, and imagination hold sway. For the male, the (inner) anima represents all that

the (outer) persona cannot manifest: the emotional, intuitive, and invisible. The anima is the personal link with the collective unconscious and provides the balance with the persona, which is always concerned about image, order, and societal values—hence she is called the subject.12 The anima is the link with the deeper and more spiritual forces, which manifest to the

conscious mind as symbols and shape every decision, act, and perspective. Jung accounts well for the power of symbol in human experience, for it is through symbols that the conscious mind accesses the rich pattern of meaning available from the unconscious. The unconscious holds personal memories that influence the individual, but it also holds a deeper layer of

primordial images common to all humans. These living psychic images are called archetypes, inherited by all humans at birth. Symbols manifest the primordial material to the individual through dreams and imagination, as well as in religious and cultural myth, ritual, and iconography. There are definite benefits in regarding the

dakinl through the lens of the anima construct.13 Like the anima, the dakini manifests in a manner that is immanently personal while representing a perspective on reality that is vaster and more profound. She appears in dreams, meditation, or visions, taking a variety of

forms, both wrathful and peaceful. She is frightening, for she represents a realm beyond personal control, and she wields enormous power. And through the sacred outlook that is part of the Vajrayana commitments, she is every human woman encountered. If she is recognized, she can transform the individual in ways that lead to greater awakening; thus she is

said to hold the keys to transformation. There are other ways in which the comparison between the anima and the dakinl can be misleading. The first, most problematic area relates to Jung's ideas concerning the contrasexuality of the individual and the anima.

Jung's ideas about the anima (and the corresponding animus, the inner subject of women) have come under scrutiny because they essentialized gender notions, caricatured masculine and feminine traits, and fell into what James Hillman called the "fantasy of opposites." It is important for Western interpreters of the dakinl to understand these

criticisms, for the same charges could be made against their work. In the fantasy of opposites, everything in human experience is polarized into oppositions, which are further qualified by other opposites. The female dakini is the messenger only for the male yogin, and

in this relationship all gender traits are stylized into opposite tendencies, forcing all human experience into stereotypic views of gender. When this contrasexuality has no corresponding daka for the female practitioner, many problems arise for Western interpreters.14 This fantasy of opposites has placed undue pressure on the anima to serve whatever is neglected in human psychology, and because of this the precise meaning of the anima paradigm has become seriously diluted in

Jungian studies. Under the rubric of this fantasy, there is a rich trade of "smuggled hypotheses, pretty pieties about eros, and eschatological indulgences about saving one's soul through relationship, becoming more feminine, and the sacrifice of the intellect."15 When this fantasy of opposites is applied to the symbol of the dakini, much is projected onto her that is not indigenous to her tradition.

The contrasexual dilemma also relates to another area in the overapplication of the anima paradigm to the understanding of the dakinl. In placing subjectivity firmly in the male prerogative, Jung neglected the spiritual subjectivities of women with relation to the anima.16 Preoccupied with his

theories, Jung confused the anima with real women and expected them to fit the image he had discovered in his own psyche. Then he developed a corresponding contrasexual theory of the animus, which he described as the inner unconscious of women, a theory to which his women patients could not fully subscribe.17 Similar perplexities can be found in the interpretation of the dakinl when scholars have tried to understand the application of the anima paradigm to the experiences of women and men. As greater numbers of hagiographies of yoginls emerge, it is clear that dakinls play a key role in the spiritual journeys of

Tibetan women practitioners, guiding, teaching, and empowering them. The content of these appearances, however, is different for women than for men, as we will see in chapter 7.18 In addition, in relationship with the male yogin, the dakinl is not all that "other," for she embodies many qualities that she shares with him. Yogins also experience visionary relationships with male gurus and yidams that are significant in ways similar to those with visionary dakinls.19 Several women scholars have challenged the contrasexuality of the dakinl. As Janice Willis commented, "The dakinl is the necessary complement to

render us (whether male or female) whole beings." And Janet Gyatso concluded that it is inadequate to consider the dakinl as an "other," for "Buddhist women need dakinls to help them loosen their attachments too."20 A second general area of concern about Jungian interpretations of the dakini comes from Jung's reification of the psyche and of archetypes and its incompatibility with Buddhist principles, especially the teaching concerning sunyata, or the emptiness of inherent existence both of the self, in whatever guise, and of projections.21 Jung understood the archetypes such as the anima to be a priori

categories with status and inescapable power, analogous to God. He used words such as "sovereign, ominiscient, and unchanging" to refer to the archetypes. "The archetypes are the great decisive forces, they bring about the real events, and not our personal reasoning and practical intellect. . . . The archetypal images decide the fate of man."22 The first problem with this interpretation has to do with Jung's ideas concerning projection. For the human who has not yet individuated, the

archetypes are manifest through projections, which are taken to be real. For Jung, the projections are less real than the anima and less real than the psyche that perceives them; the projections are mere phantoms of the vital power of the archetypes. For this reason, Jung became trapped in a subjectobject dualism in which the subject was more real than the object. This dooms Jung to solipsism, a closed world in which the perceived is nothing other than an expression of the self that perceives it.23 Jung's stance on this matter creates special difficulties in gender discussions. By implication, the polarity

between male and female is insurmountable, causing unendurable alienation and suffering. If the perceiving subject is more real than its projections, the "other" can never be reconciled, and the psychic and spiritual search is doomed. When both sides of the polarity are grounded in emptiness, this potential alienation is nothing but a temporary obscuration. These flaws also raise concern when they are applied to Tibetan Buddhism, in which the unconscious has no ultimacy. The dakinl is a symbol that expresses in feminine form the fundamental ground of reality, which is the utter lack of inherent existence of every phenomenon, whether relative or absolute. Applied to Jungian notions, Buddhism discovers that the self has no inherent reality, nor does the psyche, the projections, the unconscious, or the archetypes. All phenomena arise as dreams within the vast and luminous space of emptiness. The dakinl is, above

all, a nonessential message of this realization. Her nature is beyond limitation of any kind, including gender. For this reason, the dakinl is a symbol in the sense described above, capable of inspiring a transformation beyond gender issues, social roles, and conventional thinking of any kind. As for the irreconcilability of masculine and feminine that remains in Jung's interpretation, the Tibetan spiritual path transcends these dualities in enlightenment, in which duality has no snare. The highest realization is one in which gender dualities are seen as "not one, not two" and all apparent phenomena are

understood for what they are. There is finally no projector, no projection, and no process of projecting. This is called Mahamudra, the great symbol, in which all phenomena are merely symbols of themselves.24 In the context of our previous discussion of the complexity of symbols in influencing the subjectivities of women and men, it is clear that there are certain limitations imposed by a Jungian interpretation. The contrasexual framework of the anima and animus overly manipulates the dynamic of

gender symbols in a way that conforms no more to the power of gender symbols in Tibetan religion than it does to the actual experiences of men and women. In my interviews with Tibetan lamas, they described the dakinl's influence on yoginls and yogins in a fluid fashion without consistent contrasexual symmetry. However, there are some real benefits in employing Jungian ideas in interpreting the dakinl. Once the contrasexual dilemma (expressed in the

fantasy of opposites) and the reification of the psyche and archetypes have been corrected, the anima sheds light on an understanding of the dakinl, as we have discussed. But those who employ an understanding of the anima in interpreting the dakinl must have a broader range of interpretation at hand in order to comprehend the unique elements of the dakinl symbol. The pervasiveness of the Jungian paradigm in examination of the dakini emphasizes contrasexuality, the ultimacy of gender imagery, and psychological interpretation. These emphases have precipitated a blizzard of feminist objections, and no wonder. However, that critique may be directed more toward Jungian tenets than toward Tibetan Buddhism, which has not been properly represented in Western interpretation.

Feminist Interpretations of the Dakinl: Problems and Promise In Western Judeo-Christian religion, prevailing patriarchal patterns have inspired a variety of feminist responses as women and men seek a religious life that promotes awakening free from gender bias. Some of these responses have discarded Christianity and Judaism completely, finding them irredeemably

patriarchal, particularly in the male identity attributed to the godhead. These proponents have often turned to new religious forms, some of them consciously reconstructed, based on so-called prepatriarchal goddess religions.25 Given the patriarchal legacy of Western religion, it is understandable for feminisms to seek their religious birthright outside of Western sources. India and Tibet have been natural places for feminist spiritualities to turn, because of their rich heritages of goddess traditions in religious contexts in which the ultimate reality is not gendered. For this reason, the work of feminist scholars of Buddhism has been influential in unearthing legacies that might nurture a feminist religious life. Recent work focused on the dakini has been strongly influenced by

these feminist considerations. This work has fallen into two general critiques. One identifies the dakinl as a construct of patriarchy drawn by a primarily monastic Buddhism in Tibet into the service of the religious goals of male practitioners only. The second perspective identifies the dakinl as a goddess figure in a gynocentric cult in which females are the primary cult leaders and males are their devoted students. These considerations have done much to

simultaneously polarize and confuse those who wish to understand the dakini in her Tibetan context.26 The central concern of these interpretations is the dakini's gender. The German scholar Adelheid Herrmann-Pfandt published a comprehensive scholarly study of the dakini drawn from Tibetan tantras and biographies.27 The feminist critiques in this work were built upon a Jungian interpretation of the dakinl, and her monograph has influenced recent American studies such as Shaw and Gyatso. Herrmann-Pfandt noted that while Tibetan tantra was more inclusive of the feminine than Indian Mahayana Buddhism, women

were exploited on a subtle level since the dakinl was understood only in terms of the male journey to enlightenment. The central point of her focus on the dakini was her contrasexuality in relationship with the tantric yogin. Whether as visionary guides to the yogin or as human counterparts, women in tantric texts were not depicted as autonomous beings who could use the dakinl imagery in service of their own liberation. Herrmann-Pfandt's conclusions were that the dakinl is an example of the exploitation of women, while her human counterpart is subservient to the yogin in a patriarchal religious context.28 June

Campbell's Traveller in Space critiqued Tibetan Buddhist patriarchal monastic and religious systems, demonstrating that women have been systematically excluded from Tibetan religion, serving only in marginal observer roles. She criticized the patriarchal matrix of power in which young boy tiilkus are taken from their mothers' arms at a young age to be enthroned, raised, and trained by an exclusively male monastic establishment. Human women are removed

from any actual influence in these young lamas' lives; instead, they are replaced by an abstract "feminine principle," manifesting as mythical dakinls or Great Mothers and remaining ethereal and idealized, sought after by lamas "in reparation for their own damaged selves."29 Campbell critiqued Tibetan notions of the dakini, remarking that she is "the secret, hidden and mystical quality of absolute insight required by men, and . . . her name became an epithet

for a sexual partner." The lama, however, retains the power of the teachings and transmits their meaning while using the abstract feminine as a complement. The female body and subjectivity are then coopted completely by the patriarchal system. This, she maintained, is damaging for women, for they can never be autonomous teachers or even practitioners in their own right, and they are kept under the dominion of male Tibetan hierarchies. For this reason, the dakinl

can only be understood as a symbol of patriarchal Buddhism that guards male privilege. Campbell concluded that dakinls, "travellers in space," are emblems of patriarchy, inaccessible to and even dangerous for the female practitioner, whether Tibetan or Western.30 While certain feminists have labeled the dakini a purely patriarchal construct, others have idealized her as a goddess with special saving power for women alone. Miranda Shaw's Passionate

Enlightenment reassessed women's historical role in the formative years of Indian Vajrayana. Although her focus is primarily Indian Buddhist, her work has often conflated Indian and Tibetan, and Hindu and Buddhist, sources. The result is a depiction of a medieval Indian gynocentric cult in which women have a monopoly on certain spiritual potentials and are ritually primary while men are derivative. This is the reason, she wrote, that "worship of women (stripuja)" is shared by tantric Hindus and Buddhists. The theoretical basis of this is that "women are embodiments of goddesses and that worship of women

is a form of devotion explicitly required by female deities."31 For Shaw, the Tibetan version of the dakinl is a cultural remnant of the prepatriarchal period of tantric Buddhism in India. She suggested that women played pivotal roles in the founding of tantric Buddhism in India, serving as gurus and ritual specialists with circles of male disciples. As Buddhism spread to Tibet, women no longer played ritual or teaching roles. Instead, as Shaw argued, Tibet shaped the dakinl symbol into an abstract patriarchal ideal who serves the spiritual paths of male yogins only, in betrayal of her historical roots.

These interpretations of the dakinl have certain common features that merit general discussion. All have inherited from Western scholarship's Jungian bias certain contrasexual assumptions regarding the dakini's role on the tantric path. These assumptions follow the contours of the fantasy of opposites, in which gender becomes stereotypic, essentialized, and androcentric, unlike many of the source materials themselves. This creates a theoretical model in which the feminine is idealized and made to serve "all

that man is lacking and for which he yearns." With this interpretation as background, it is no wonder that feminist critics would challenge this dakinl as a construct of male fantasy and an abstract patriarchal principle. When one calls into question the Jungian bias of Western scholars, the basis of this feminist critique is also disputed. An additional problem arises when mythic and symbolic material is taken to have historical significance. In her desire

to "reclaim the historical agency of women,"32 Shaw employed methods of feminist historiography to reconstruct a history of women in early tantric Buddhism in India. Drawing from early tantras attributed to dakinls, she interpreted these to be authored by historical women and from their coded language constructed a gynocentric cult in which women were the ritual specialists and men were the apprentices. Employing "creative hermeneutical strategies,"33

Shaw concluded that these sources reveal a great deal about women and gender relations in the tantric movement. In her account, the dakinl appears as support and patron of women qua women, serving as their exclusive protector in a gynocentric cult. Certainly there is ample precedent for Shaw's method, but it is difficult to discern anything authentically traditional about the dakinl from her interpretations, as she drew historical conclusions from

symbolic tantric literature. In this case, as in the critiques of Campbell and Herrmann-Pfandt, the conflating of historical and symbolic has probably created greater perplexity over the identity of the dakinl than the Tibetan tradition could have ever produced. These feminist interpretations of the dakinl have followed certain methods that draw conclusions about the historic or contemporary lives of women from a study of feminine symbols, in this case in Tibetan culture. This methodology has been critiqued in many works; in the case of Tibet, Anne Klein and Barbara Aziz have demonstrated that there is a

distinction to be drawn between the seemingly egalitarian symbol of the dakini and the lives of women in Tibet.34 Certainly they and other scholars have indicated the strong connection between these two realms of experience, but the actual nature of the connection is not easily discerned. In order to enter this realm, one must delve more deeply into the realm of religious phenomena, especially symbols. In order to responsibly analyze issues of gender in religious phenomena, three kinds of phenomena must be distinguished, each requiring differing methods: tenets or doctrines, social institutions, and systems of symbol and ritual. Studies of gender in the Buddhist tradition suggest a general

pattern of institutional patriarchy accompanied by a contrasting doctrinal promise of the inherent spiritual capabilities of women.35 This means that in the institutional structures of authorization of teachers, monastic education, writing and recording of texts, and ritual specialization, women in Asian traditions have been excluded from more than occasional positions of power and responsibility.36 Insofar as women have been seen as threats to the

renunciant path of male practitioners, attitudes toward them have been misogynistic, regarding them as evil seductresses who were snares of the tempter, Mara. Yet the core teachings of Buddhism reflect confidence in women's wisdom and potential for enlightenment. Still, when examining only the doctrinal and institutional aspects of Buddhism for gender bias, it is easy to become disheartened. Little has been done in the area of symbol and ritual, especially within Tibetan Buddhism, which is particularly rich in these aspects. Symbols have tremendous potential to shape the spiritual journeys of male and female practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism. Gender symbols are pivotal in Tibetan symbol systems, providing expression for the dynamic qualities of phenomenal existence. Enlightened feminine and masculine symbols populate the painted scrolls and ritual texts of Tibet, suggesting a sacredness of gender so longed

for in Western religion and feminism. How are these symbols to be understood? Do they have relevance for understanding the identities and values of humans? Such questions suggest the complexities of examining gender symbolisms and their implications for human life. In examining these symbols more deeply, it is important to identify their structure and presentation as well as the contexts in which they are practiced. At the same time, there is a stream of the

feminist critique regarding the dakinl that must be seriously considered in order to fully portray the actual power of gender symbols within culture. This is important because, while symbols have a distinct realm of structure and meaning, they deeply influence institutional life and doctrinal development in any tradition, though not in predictable ways. Whether or not one is sympathetic to feminist concerns, this feminist critique must be understood and

considered. It says this: when female representations such as the dakinl pervade the Tibetan Buddhist symbolic world, they appear as abstract representation for the benefit of male practitioners only. Whether these female symbols are depicted as chaste or dangerous, visions of beauty or horror, cultural patrons or destroyers, they are described through the eyes of male

practitioners, whether hierarchs or laymen. When women are defined in a patriarchal society like Tibet, their gender "can be exploited as a movable entity to be used to reflect men's sense of 'other' or to be abstracted to the transcendental, when the acknowledgment of her subjectivity, by-and-forherself, becomes problematic for them."37 June Campbell and Adelheid Herrmann-Pfandt have suggested that this is the case with the dakinl symbol, an abstract,

objectified feminine as seen through the true religious subject of Buddhist culture, the male.38 According to this view, women practitioners are deprived of their personal subjectivity. In order to follow this critique, it is important understand the meaning of subjectivity in the context of feminism: a sense of agency and power at the heart of personal identity.'9 The critique continues: if religious practice is to be personal and dynamic, practitioners must experience spiritual subjectivity in which their full engagement is apparent. This is difficult in androcentric settings in which power rests in male

hands and women are objectified in a variety of ways. In patriarchy, the male is considered the paradigm of humanity, and the female is a variation of the norm. Because of this, media of communication, ways of knowing, and social forms shaped by men are considered normative. Because women's styles and forms often rest outside these norms, they are viewed as objects from the point of view of male privilege. Women achieve a temporary, precarious seat within

normative realms only by receiving approval from men when they exhibit compliant qualities of objectified beauty, service, and submission. From this perspective, women do not fit within the androcentric definition of humanity and are objectified as the "other," treated as things to be controlled, classified, idealized, or demonized. In religious life, according to this critique, males are the religious subjects who name reality, institutional

structure, religious experience, and symbolic expression, and women are presented only in relation to the experience of men, as seen by men.40 In the case of gender symbolism, female representations are depicted in an abstract form in service of male spirituality and through male projection and idealization. From this perspective, the Virgin Mary is the idealized purity of unconditioned love, Athena represents civility overcoming raw emotion, and Slta is the ideal and submissive wife. But from the view of certain feminist critiques, these feminine symbols all serve the male subject. It is true that subjectivity is of vital importance to women's experience,

for it relates to the formative and meaningful aspects of female identity, which stand in contrast to culturally constructed male styles. For example, a specific female subjectivity values those experiences unique to biology and processed through Western patriarchal culture—experiences of birthing, mothering, and nurturing. These experiences have fostered in many women's lives a subjectivity that values nonconceptual, nonverbal wisdom as opposed to conceptual or logical knowledge, and that understands a somatic, visceral awareness associated with embodiment. The tendency to use this orientation as a

stereotype of a universalized biological difference has, of course, been rejected by many feminists as an essentialist approach to sex roles.41 Yet women's subjective experience has often been denigrated or ignored in androcentric settings. In androcentric settings, the critique continues, women often have difficulty placing themselves within religious life as active subjects of their own spiritual experience, especially in relation to gender symbols. Within their traditions, few choices are available. Either women can ignore their female gender and identify themselves as a kind of generic "male," dismissing any obstacles they may face in the practice of their spirituality. In this case, women may avoid gender symbols of any kind as reminders of the peril of gender identity in religious practice. Or they can make a relationship with their female gender by seeing their bodies and emotions through men's eyes.

Feminine symbols provide a paradigm for the objectified female, and women may subjectively experience their own gendered bodies in this abstracted way. Liz Wilson explored the issue of gendered subjectivity in Buddhism in her work on representations of women's bodies in first-millennium Buddhist India and Southeast Asia.42 While women were widely excluded from monastic life, their bodies appeared prominently in hagiographic literature as powerful objects of male desire and renunciation. When they were young and beautiful, women's bodies enticed men into fantasy and lust; when they died, their bodies rotting in the charnel ground evoked deep abhorrence. When women were depicted in rare instances as subjects in this hagiographic literature, how did they experience their own bodies? Wilson showed that nuns from the Therlgatha became enlightened contemplating the impermanence of their own bodies. The former courtesan Ambapali examined her body in her declining years, as if standing in front of a mirror, surveying sagging flesh and deepening wrinkles in a classic contemplation:

My hair was black, the color of bees, curled at the ends; with age it's become like bark or hemp— not other than this are the Truth-speaker's words.

My hair was fragrant, full of flowers like a perfume box; with age it smells like dog's fur— not other than this are the Truth-speaker's words. . . .

Once my two breasts were full and round, quite beautiful; they now hang pendulous as water-skins with water— not other than this are the Truth-speaker's words.

My body was once beautiful as a well-polished tablet of gold; now it is covered all over with very fine wrinkles— not other than this are the Truth-speaker's words.**

Ambapali compared her aging body with the desirable, objectified form seen by her patrons when she was in her prime. Finding it to be other than its previous projections, she saw nothing of value remaining in cyclic existence. In this contemplation, Ambapali followed the androcentric convention of contemplating the decaying body, attaining enlightenment by interacting with herself as an object.44 For feminism, neither ignoring one's female gender nor subjectively experiencing oneself through patriarchal eyes is a satisfactory option.45 The natural responses are those pursued by our feminist critics. Either one must disown the dakinl as a construct of patriarchal fantasy having little of genuine benefit for women practitioners, or one can attempt to reconstruct a Utopian, gynocentric past in which women were the agents of ritual or symbol.46 Although each of these options pursues the dakinl, she actually becomes lost in what is an essentially ideological though wellintentioned endeavor. What is needed is a fresh reexamination of the dakinl in her Tibetan context, utilizing methods from the history of religions and from gender studies to identify her meaning as a gendered symbol of Tibetan Buddhism. Yet, in these investigations, it is appropriate to take up the topic of subjectivity in this broader context to identify the dynamics of the dakinl symbol in meditative practice and ritual celebration, which we will do in the next section.

The Complexity of Religious Symbols: Spiritual Subjectivity

Subjectivity is an important topic in the study of religion, especially the power of symbols to evoke a sense of inner meaning in the lives of women and men. Symbols are a structure of signification that has at least two levels of import. One level is primary and literal, drawn from ordinary experience, expressible in words and ordinary images, and susceptible to conventional interpretation. This first draws us to another level that is profound and

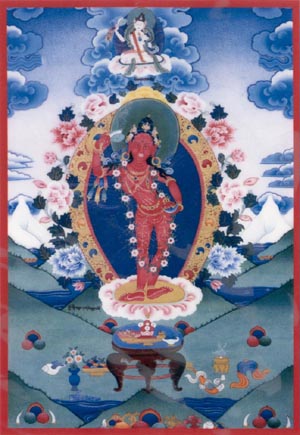

directly inexpressible and that lends itself only reluctantly to interpretation. The second level comes before language or discursive reason and defies any other means of knowledge. It is not merely a reflection of objective reality but reveals something about the nature of the world that is not evident on the level of immediate experience. Psychoanalysis and the arts speak of this area as the unconscious or the creative; in the history of religions it is called the sacred. In Tibetan tantra, symbols are of central importance, and dakinls are the prime purveyors of symbol with their physical appearance, their gifts, and their styles of communication. Their meanings are difficult to discover, and they are often not recognized even by the initiated. But for those

who are spiritually prepared and open, the depth of the dakini teachings is realized and the dakini's gifts can be received. Exploring symbols is always personal. They lead into a more intimate experience of meaning on an inner reflective level at the same time that one is exploring the dynamics of the evident world. Symbols bridge these two worlds and as such awaken individual experience into realization and action. From this point of view, one's place in the cosmos is not an alien one; instead, in a symbolic sense, one is completely at home. In this way, the meanings arising from exploring symbols reverberate through experience, sensitizing one to a new realm of understanding. Symbols find expression in concrete elements of our world. They are

expressed in images, through iconography and art; they are expressed in words, in ritual and narrative; and they are expressed in actions. Yet, when we attempt to express the deeper experience of symbol, we must do so metaphorically, poetically, or artistically, for these expressions themselves are merely tools, which are not identical with the symbol itself. Dakinls speak often in highly symbolic language employing ordinary, earthy imagery in order to convey subtle, personal meanings. For example, the visionary dakinl offers treasure boxes, skulls, or shells, but these gifts cannot

express the profundity of the recipient's experience. "Language can only capture the foam on the surface of life," wrote Paul Ricoeur.47 Symbols are opaque, for they are rooted in inexpressible experience, and "this opaqueness is the symbol's very profundity, an inexhaustible depth."48 For this reason it can be said that symbols are truly multivalent, simultaneously expressing several meanings that do not appear related from a conventional point of view.

The wrathful appearance of a dakinl who gnashes her teeth and threatens the practitioner may be experienced blissfully and joyfully; the beautiful dakinl vision or dream may be experienced with great fear and trepidation. Symbols have the ability to convey "paradoxical situations or certain patterns of ultimate reality that can be expressed in no other way,"49 communicating on several levels at once and evoking meaning far beyond the literal words. The greatest power of symbolism is in the formation of personal subjectivity. Subjectivity in this sense refers to the dynamic empowerment of personal inquiry,

emptying the narrow, self-centered concerns into the vaster perspective evoked by the symbol.50 Dakinl visions have the power to arouse the tantric practitioner in all areas of spiritual practice, for she represents his or her own wisdom-mind, the nature of which is inexpressible. Symbolic representations and appearances have tremendous power to shape the spiritual subjectivity of all religious practitioners, engaging them at the heart of

their own spiritual journeys. We can develop no self-knowledge without some kind of detour through symbols, and through telling ourselves our sacred stories we come to know who we really are. This process of self-disclosure is the cultivation of subjectivity. In the context of Tibetan symbol systems, popular hagiographies of saints serve as narrative symbols of the practitioner's journey. When the poet-yogin Milarepa was undergoing tantric training under his master Marpa's guidance, he was asked to erect a series of stone towers in the rough landscape of eastern Tibet.51 As he finished each, his master changed his mind and demanded that Milarepa tear it down, returning the rocks and soil to their original places. With great physical hardship, personal frustration, and despair, Milarepa did as his master asked. When the practitioner contemplates these tales, the inner landscape of the spiritual journey is illuminated; its contours become more familiar and meaningful, transforming frustration and obstacles into inspiration. Symbols are not mirrors of the self or of a socially constructed reality; rather they are windows to realms beyond thought or meaning. Ricoeur

speaks of the symbol giving rise to thought,52 and when we encounter symbols in a dynamic and personal way, a sense of meaning develops as a subjective reality. In Tibetan Buddhism, these symbols are especially encountered in ritual practice. Meanings that arise in ritual practice are not the same from individual to individual; they rely on the whole context offered by the rituals themselves and on the connotations that we bring to them. The result of

this engagement cannot be precisely predicted. Yet, because of the larger context in which symbols are formed, there are consistencies in subjective experience. The formation of subjectivity is not, of course, immune to gender issues. Symbolic narratives are full of gender dramas identifying the masculine with heroic value and the feminine with objectified, weak, or dangerous qualities. These heroic myths, which have played so prominent a role in the interpretation of symbols in the West, do not compel women in the same way as they do men, for they ignore the subjective, nonverbal wisdom and embodied sexuality that is central to women's experience. How can the gender biases of symbol systems be contravened so that symbols can have unmediated

power in shaping the subjectivities of both women and men? Ricoeur outlined levels of a symbol that give a clue to appropriate methods for interpreting it in a gender-neutral manner. The primary level of the symbol is that experienced preverbally, through dreams and visions, and this level has the most direct influence on the shaping of personal subjectivity. This can be seen in the tantrika's visionary and meditative experience, either in encounters with the dakinl described in the hagiographies or with the levels of meaning in personal tantric practice. Secondary symbols appear in narrative or stylized ritual, expressed in metaphorical or poetic language, one step removed from personal experience but with direct power to evoke personal subjectivity. The accounts of dakini encounters may fall into this category when they interpret rather than give the actual details of the encounters. Tertiary symbols take the form of doctrine, philosophic expression, or societal forms, and they are most subject to the gender biases and interpretations imposed by culture. Examples of tertiary symbols can be found especially in the derived understanding of the kinds of human dakinls in tantric literature. While this material is important, it plays a secondary role in our study of the dakinl symbol. Ricoeur suggested that encountering a symbol requires a dynamic engagement made up of two aspects. First, the subject must consent to the

symbol, engaging with its power and letting it reverberate in her or his experience. In Vajrayana, this consent is associated with devotion to the tantric guru and maintaining the commitments and vows, without which the practice cannot bear spiritual fruit. At the same time, the subject must allow the emergence of a critical quality that Ricoeur terms "suspicion."53 This attitude of suspicion requires us to question aspects of our experience of the symbol, identifying its essential qualities as opposed to phantasms created by cultural overlay. Vajrayana practitioners are encouraged to bring their

critical intellect and curiosity to bear in ritual practice, even while retaining the fundamental consent necessary for successful accomplishment of the practice. A healthy balance of these two views is necessary in order to personalize and deepen one's understanding of the power of the practice beyond mere forms. In this context, it is important to scrutinize a symbol, deconstructing its levels to the most personal. In the case of the dakinl, this entails deconstructing the overly theoretical or mythologized dimensions of her manifestation in favor of her visionary and essential aspects as they are experienced by the Tibetan Buddhist practitioner. For example, when the dakini is directly experienced in the practice of her ritual and in formless practice, her reality is unmediated. When she is encountered through hagiographic accounts, the subjective experience of her meaning is possible especially

if the ritual or visionary experience accompanies the reading. The most removed aspect of the dakinl is the doctrinal formulation in which overlays of interpretation obscure her meaning. When the symbols are allowed to directly influence the practitioner's spiritual subjectivity, the authentic experience of the dakinl symbol is available. The direct experience of the dakinl happens especially in the context of consent, in which the practitioner is devoted to the guru and maintains the Vajrayana commitments. Having fully consented, the subject may reconstruct the symbol into meaningful myths, stories, and paradigms concerning the dakini. This dialectic of consent and suspicion becomes the essential way in which the full range of the dakinl symbol may empower the subjectivity of the practitioner.54 In the study of the dakinl, it is essential to emphasize how she is described in terms of dreams and visionary experience on the one hand and meditative and ritual expression on the other. Hagiographic material is also an important facet of her interpretation, especially when informed through the perspective of meditative realization. This preference suggests a methodology that ranks doctrinal formulations and metaphysical specu

lation at a lower level. However, in order to find coherence between the symbol of the dakinl and the rich commentarial traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, it is important to contextualize the symbol of the dakini within an overall understanding of Vajrayana. There is no evidence that gender symbols play favorites in the structuring of gendered religious experience. For example, feminine symbols cannot be said to serve in the formation of the subjectivity of only women, nor masculine symbols to have power only for men.55 In Tibetan Buddhism, the rituals of female deities are essential for both men and women

practitioners, as are the rituals of male deities. Symbols of both genders function in an interconnected way in vital symbol systems, such that feminine symbols have potency for both men and women, though in somewhat different frameworks of interpretation. Ironically, the importance that feminism (or patriarchy, for that matter) places on gender identity may prove an obstacle to experiencing the full power of symbols in the formation of spiritual subjectivity. For example, if practitioners with feminist inclinations insist on the practice of only female deities, a whole dimension of tantric ritual is missed. When we identify too fully with our gender, it may be impossible to discover the transformative effect of symbols. As a woman, can I fully

identify with the confusion of the isolated yogin who supplicates the dakini for help, or with the travails of a beleaguered male disciple confronting the demands of the male tantric guru? If I cannot, I have shut myself off from much of the symbolic power of tantric Buddhism. One of the reasons this is true is that the cultivation of spiritual subjectivity entails stepping beyond the confines of rigid control. Ricoeur was perhaps the most articulate in demonstrating that symbols shape the formations of the self through an intimate process of opening and letting go of ego-centered concerns. As he so vividly noted, when reading a text that conveys symbolic content, "I unrealize myself."56 When humans experience themselves as spiritual subjects, they

find that they are agents who, in the process of spiritual transformation, open to power beyond the narrow confines of the self. This means giving up their hold on concepts of gender identity, along with other ego-centered concerns. The way in which subjectivity unravels concepts concerning personal identity is traced in Buddhism in the process of meditation. Anne Klein described how meditation practice places attention first on the contents of mind, but viewing thoughts, emotions, and sense perceptions from the

perspective of how the mind is.57 One generally regards personal subjectivity according to the plotlines of identity—I am a woman, I am a Buddhist, I am reading this book, I am thirsty, my neck aches. But when one exposes the experience of subjectivity to meditation practice, one finds a more subtle sense. First the attention is placed on these details, steadying and settling the mind. Then one notices the patterns of mental contents and, eventually, recognizes the dynamic of the mind itself. One discovers that pervading all the contents of experience is an awareness of the present moment, an awake and

clear cognition that illumines the details of mental processes. This cognition is not composed of thoughts, emotions, or sense perceptions, though it pervades them; its experience is nonconceptual and nonverbal. This awareness is inherent in the nature of the mind and depends on nothing outside of itself. It is through this awareness, according to Buddhism, that humans can be said to have subjectivity at all. This fundamental "subjectivity without contents" is the empty center of all our experience, which Klein called "a different experience of subjectivity, of mind itself."58 The most intimate level of the experience of the symbol of the dakini is this nonconceptual "without contents" level, as we shall see in chapter 4. But the contentless

subjectivity discovered in Buddhist meditation is not averse to contents; in fact, it ceaselessly gives rise to symbols that wordlessly express the profundity of its meaning. The dakinl in her most profound level of meaning is beyond form, gender, and expression, but "she" gives rise to bountiful forms and expressions, which sometimes take the female gender as a way to express "her" essence. In this communication, the dakini holds the key to understanding the relationships between emptiness and form, between wisdom and skillful means, and between female and male. This communication has a liberating message to offer the Western practitioner burdened by the politics of gender and confused by the dualities of cyclic existence. In recent scholarship on gender

symbolism, feminist assumptions concerning the limitations of androcentric symbols have been given new perspective. Women and men experience religious symbolism in different but personally transformative ways.59 In her research on the religious lives of medieval Christian women, Caroline Walker Bynum discovered that feminine symbols functioned in a different way for medieval women than for medieval men. While both men and women saw God as male and the soul as female, she argued that this interpretation socially empowered women

while reversing cultural views of power and status held by religious men. For example, when men became "brides of Christ" their symbolic understanding reversed their culturally based gender experience. There was no question that the medieval women she studied perceived themselves as spiritual subjects. While they actively engaged in prayer, ascesis, and good works, contemporary questions of personal gender identity had no role in their spiritual lives.60 Bynum's work led her to the conclusion that a study of symbol, myth, and ritual does not lend itself as easily to feminist methods of scholarship as do

studies of institutional structure and theology. Her conclusions on the complexities of gender are two. First, in accord with the discoveries of feminism, it is clear that all experience is gendered experience. There is no generic human, and the experiences of men and women in every known society are different precisely because of gender. Second, religious symbols transform gendered experience beyond societal expectations and endow it with abundant religious meaning. There is no way to accurately predict the effect of a gender symbol on the perceiving subject, for the symbol may support, reject, or invert cultural meanings of gender. When one asks what a gender symbol means, one must also ask for whom.61 These conclusions, of course, question the narrow range of interpretation of the dakinl symbol that has characterized Western scholarship for at least the past twenty years. These approaches suggest

that the gender of the dakinl may have something to do with understanding the female gender, but a great deal to do with meanings having nothing to do with gender. Openness to the full range of the dakini's meaning yields the full richness of her symbolism. From this perspective, we may understand why the encounter with the dakinl is important for every tantric Buddhist practitioner, whether male or female. She represents the most intimate aspects of the spiritual path. She is the fundamental nature of the mind; she guards the gates of wisdom for the practitioner and the lineages of tantric teachers; she holds the key to the secret treasury of practices that lead to realization; and she manifests variously in her support of authentic meditation. To limit her meanings only to those of gender concerns would be to miss much of what she has to offer. However, as we shall see in chapter 7, she is experienced slightly differently by male and female practitioners. The dakinl appears in visionary form to both yogins and yoginls at key points in their spiritual journeys,

at times of crisis or intractability. But in her appearances to the yoginl, the dakinl is more predictably an ally and support, often welcoming her as a sister and sometimes pointing out her own dakinl nature. For yogins, the dakini is more likely to to be perceived in threatening form, especially as a decrepit hag or an ugly woman of low birth. These appearances have the effect especially of shocking the yogin out of intellectual or class arrogance and turning his mind to the dharma. Among the dakini's many gifts, she gives a blessing of her radiant and empty body to her subjects. The ways in which she

bestows her body gifts differ slightly, depending upon the gender of the recipient. The dakinl acts as a mirror for the yoginl, empowering her view of her body and life as being of the same nature as the dakini's. For example, contact with the dakinl restores health and extends life for all practitioners; for the yoginl, this contact rejuvenates her sick and aging body quite literally. In terms of sexual yoga, the dakinl gives her body gifts in the form of sexual union to yogins, whereas for yoginls she selects suitable consorts. Finally, the yoginl is likely to manifest as a dakinl at some point in her spiritual development. For some yoginls, the physical marks of a dakini are present at birth; for others the signs and powers manifest at a later time. But

the yoginls in the namthars are likely to be perceived as dakinls by their students at the point of their full maturation. The patterns with regard to dakinls accord in some ways with preliminary observations made by Bynum and her colleagues concerning certain patterns in men's and women's experience of gendered symbols drawn from a variety of religious traditions. Men and women in a given tradition, working with the same symbols and myths, writing in the same genre, living in the same religious circumstances, display consistent patterns in interpreting symbols: Women's symbols and myths tend to build from social and biological experiences; men's symbols and myths tend to invert them. Women's mode of using symbols seems given to the muting of opposition, whether through paradox or through synthesis; men's mode seems characterized by emphasis on opposition, contradiction, inversion, and conversion. Women's myths and rituals tend to explore a state of being; men's tend to build elaborate and discrete stages between self and other.62

Tibetan Buddhism developed its own unique understanding of gender, though in a context somewhat different than the contemporary concerns of Western culture. Questions of personal identity and gender are generally considered a contemporary Western phenomenon. In traditional Tibetan culture before the Chinese occupation in the 1950s, every detail of cultural life was infused with religious concerns such as the appeasement of obstructing spirits, the

accumulation of merit, and the attainment of enlightenment. There is every indication that in areas of Tibet outside of Lhasa, these conditions remain to a greater or lesser extent.63 For Tibetans, concepts of "feminine" and "masculine" have been important only to the extent that they reflect this ultimate dynamic in ritual and meditation. Gender has been understood to be beyond personal identity, a play of absolute qualities in the experience of the practitioner. For Tibetans, the "feminine" refers to the limitless, ungraspable, and aware qualities of the ultimate nature of mind; it also refers to the intensely dynamic way in which that awareness undermines concepts, hesitation, and obstacles in the spiritual journeys of female and male Vajrayana practitioners. The "masculine" relates to the qualities of fearless compassion and actions that naturally arise from the realization of limitless awareness, and the confidence and effectiveness associated with enlightened action. From this sacred view, the embodied lives of ordinary men and women can be seen as a dynamic and sacred play of the ultimate expressing itself as gendered physical bodies, their psychologies, and their states of mind. For traditional Tibetan Buddhism, this dynamic is merely one among a universe of polarities that are ordinarily taken as irreconcilable. For the mind ensnared in dualistic thinking, these polarities represent the endless dilemmas of life; for the mind awakened to the patterns of cyclic existence, these extremes do not differ from each other ultimately. Seeing through the seeming duality of these pairs, using the methods of Vajrayana practice, transforms the practitioner's view. As we discussed earlier, this general sacred view of gender was not necessarily reflected in Tibetan social life.64 In general, women have en

joyed more prestige and freedom in Tibet than in either China or India wielding power in trade, in nomadic herding, and in the management of large families. Still, generally speaking, women were subject to their fathers and husbands. Their spiritual potential was generally valued, but, as in the Indian context, women were generally denied full monastic ordination education, ritual training, teaching roles, and financial support for their dharma practice. And while there exist hagiographies of remarkable female teachers and yoginis of Tibet, it is clear that these women were rare exceptions in a tradition dominated by an androcentric and patriarchal monastic structure and system of selection of reincarnated lamas (tiilkus). In these aspects, the patterns from the Indian heritage of Buddhism were carried on to Tibet. Buddhist teachers in Tibet often engaged their potential disciples by encouraging them to contemplate the fruitlessness of worldly concerns, whether they be gain or loss, pleasure or pain, fame or infamy, or praise or blame.65 Painful

situations in everyday life were considered excellent incentives for dharma practice. When such realities as the fragility of life and the certainty of death are contemplated, the mind naturally turns to dharma practice. When women contemplate the intractable obstacles they face because of their gender, these are not feminist reflections; they are dharmic contemplations that initiate them to the tantric path. Princess Trompa Gyen summarized her dilemma to her guru in this way:

Our minds seek virtue in the Dharma but girls are not free to follow it. Rather than risk a lawsuit, we stay with even bad spouses. Avoiding bad reputations, we are stuck in the swamp of cyclic existence. . . . Though we stay in strict, isolated retreat, we encounter vile enemies. Though we do our Dharma practices, bad conditions and obstacles interfere. . . . Next time let me obtain a male body, and become independent, so that I can exert myself in the Dharma and obtain the fruition of buddhahood.66

uru responded with an even more dismal depiction of her situation, ^ef ^ . mat she wandered hopelessly through cyclic existence. He nted out, "having forsaken your own priorities, you serve another,"67 '"oving from parents and siblings to husband and in-laws, slaving in the home of strangers, suffering but getting no gratitude. He concluded with the admonition, "A girl should value her own worth. Stand up for yourself, Trompa Gyen!"68 And he urged her to renounce these patterns and to practice the dharma. This is the perspective that both Gross and Aziz took when observing that the Tibetan word for woman

(kyemen), which literally means "born low " is not a point of doctrine but an insight from Tibetan folk wisdom that accurately observes the constrictions and difficulties of a woman's life under patriarchy.69 But the traditional Tibetan understanding reflects that the difficulty of a woman's life, which is readily acknowledged to be greater than that of a man's, provides her motivation to practice the dharma. Reversing the oppressions of patriarchy would merely yield different kinds of suffering. The depictions of the hardships of Tibetan yoginis in sacred biographies are not thinly veiled feminist tracts;

they are acknowledgment of the specific difficulties that women experience, which lead to a life of committed practice and successful realization. A common theme in Tibetan tantric lore is the superior spiritual potentialities of women. Women are, by virtue of their female bodies, sacred incarnations of wisdom to be respected by all tantric practitioners.70 Padmasambhava spoke of men's and women's equal suitability for enlightenment, noting that if women have strong aspiration, they have higher spiritual potential.7' Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche was heard to say that women are more likely than men to attain the

rainbow body through the practice of Dzogchen, citing the great patriarch Garap Dorje on the matter.72 There are a number of reasons for this. Having overcome more daunting hardships than men, women have superior spiritual stamina and momentum. Embodying wisdom, they have greater potential for openness and intuitive qualities. But the pitfalls for women are also uniquely difficult, and developing such religious potential entails overcoming emotionality, ego-clingmg, and habitual patterns just as it does for men. In traditional Tibet women pursued religious vocations as best they could. Spiritual practice has always been an essential part of laywomen's ^ves, as can be attested even today by observing Tibetan communities. Or women who wish to devote themselves to religious pursuits as men

do could become either celibate nuns or tantrikas, noncelibate practitioners of Vajrayana yogas. Nuns may live together in small nunneries close to their natal home, usually lacking in resources for support of education, spiritual instruction, or even appropriate food, shelter, and clothing for members.73 Tantrika women may live in monastic compounds or with family members, remaining in semiretreat in the upper reaches of the home. Or they may dwell in

solitary retreat punctuated by pilgrimages to visit sacred sites or spiritual teachers residing either in monasteries or in solitude.74 The limitations on women's institutional influence in Tibet are seen in a variety of ways. In a study of the commentarial texts of the Tibetan canon, there is little evidence of women's contributions to or even their presence in monastic life and lineages. But when study turns to the ritual and yogic dimensions of Vajrayana Buddhism, there is greater evidence of women's participation. Especially in Tibet's oral traditions, the influence of women has been evident, in storytelling, poetry, and both secular and religious songs. Examples can be found especially in the songs of Milarepa, the siddhas, and the music of the

Cho and Shije traditions.75 In addition, certain shamanic transmissions of the yogic tradition have always been carried by women, such as the delok possession, in which a woman literally dies in a visionary descent to hell realms, returning again to her human body with memories and insight gained from the experience.76 Sometimes women have served as oracles, mediating specific deities who guide the sacred and secular affairs of monastery, government, and village.77 Women have also consistently played important roles in the discovery of termas, or hidden treasure texts, but were usually cautioned not to propagate their discoveries for a requisite number of births. Until recently, Western Tibetology has paid the greatest attention to the institutional

manifestation of the tradition, almost completely neglecting the contributions, insights, and transmissions of women, which have often been seen as superstitious or merely folk traditions. Barbara Aziz noted that this is probably because the patriarchal nature of Western scholarship, which honors monastic traditions and classical texts, reinforces the patriarchal habits of Buddhist institutions in Tibet.78 Recent works have begun to correct this imbalance, showing greater interest in the shamanic or yogic aspects of Buddhism and the oral traditions and the less institutionalized aspects of the Tibetan tradition. As scholarship in this area

grows, more will be known about the transmissions and contributions of Tibetan women. Of relevance to a study of women's religious lives in Tibet is the work of Geoffrey Samuel, who argued that in the study of Tibetan Buddhism many complexities are resolved in distinguishing between two general, complementary components of religious life: the monastic (clerical) and the yogic (shamanic).79 The monastic aspects of Tibetan society concern the institutional life in which discipline, conduct, education, and power are governed by the monastic disciplinary code and by goals other than, but not necessarily contrary to, enlightenment. In contrast, the yogic dimension places its emphasis upon spiritual and societal transformation through yogic practice, relying on views of reality other than prevailing conventional norms. The yogic dimension also includes many folk elements with pragmatic ends

other than enlightenment. Samuel described how these two complementary aspects may interweave in the activities of a particular lama, yogin, or lay practitioner, and they certainly have intertwined in the development of religious institutions. But these two aspects are "rooted in fundamentally different orientations towards the world and towards human experience and behavior."80 Yogic Buddhism focuses on transformation and means of transformation. In its folk dimensions, yogic Buddhism may wish to transform conventional circumstances, as by extending life, attracting wealth, or averting disaster; or it may seek only the ultimate transformation, enlightenment. It employs a variety of ritual and visionary methods, but its power rests upon direct perception of the nature of mind and reality, which is said in Tibet to be the essence of the Buddha's experience of enlightenment. Monastic Buddhism shares with yogic Buddhism the ultimate goal of enlightenment, but it has other goals, related to monastic disciplinary codes and the continuity of monastic lineages and education. Monastic Buddhism places greater emphasis on the gradual path based upon purifying one's karma through

accumulation of merit, renouncing unvirtuous actions, scholastic mastery of texts, debate, and preserving the monastic tradition. In this last area, monastic Buddhism is concerned with power and succession and institutional life. This study focuses on the yogic tradition, especially as it was practiced and understood in eastern and central Tibet in the Kagyii and Nyingma lineages. These traditions have emphasized personal transformation based upon direct experience of a mode of reality more basic and meaningful

than conventional reality, cultivating extraordinary powers of communication and understanding in their adepts, and opening the way to enlightenment, which is ultimate freedom. In most literate and complex societies, yogic-style shamanism has been subordinated to cultural structures such as the state or institutionalized religion such as the monastery. Samuel argued that Tibet is unusual in its successful retention of a vital and energized shamanic dimension with influence upon every aspect of culture, especially outside of Lhasa and central Tibet.81 Of relevance for this study is the fact that

shamanic or yogic cultures of Tibet have relied on the visionary and symbolic dimensions of religion, nurturing their development in ritual practice and spiritual transformation. These are the areas in which the participation and leadership of women have been more evident. It is also the area in which the dakinl has been a central symbol of spiritual transformation. If we are to employ Ricoeur's strategies to retrieve the authentic symbol of the dakinl, we must turn to the shamanic or yogic traditions of Tibet, in which visionary experience and ritual practice have been so central. These strategies suggest that scholastic or doctrinal presentations are of less importance to a proper understanding of the dakinl symbol. The shamanic traditions have been

preserved primarily in the oral teachings of the Kagyti and Nyingma lineages, and it is here that we find women's participation and the prevalence of the dakinl symbol. Although Tibetan women have played a minor public role in institutional Buddhism, they have emerged in yogic lineages as teachers and holders of special transmissions and practices. They have served as founders of new lineages of teachings, as in the case of Machik Lapdron; they have played important roles in the hidden-treasure (terma) traditions of Tibet, beginning with Yeshe Tsogyal; they have developed unique practices, as did Gelongma Palmo, who conjoined Avalokitesvara practice with fasting in nyungne meditation;82 they have appeared as partners and "secret mothers" of great

yogins, teaching privately or through their life example, as in the case of Dagmema;83 they have been renowned yoginls practicing in retreat, as in the contemporary examples of Ayu Khando84 and Jetsiin Lochen Rinpoche.85 These women played yogic rather than academic or monastic roles, probably because monastic education and leadership were traditionally denied them by the Tibetan social structure. A rare exception can be found in Jetsiin Mingyur Paldron, the daughter of the Mindroling terton Terdag Lingpa, who was known for her penetrating intellect and

great learning. She was responsible for the rebuilding of Mindrdling monastery after its destruction by the Dzungars in the early eighteenth century.86 Studies of Tibetan women have appeared elsewhere, as we have discussed, and are not the specific focus of this book. However, insofar as these Tibetan yoginls have been considered human dakinls, they fall within the purview of our study and will be treated in the discussion of embodied dakinls in chapter 6. The dakinl symbol continues to be the living essence of Vajrayana transmission, the authentic marrow of the yogic tradition. While monastic establishments and philosophic systems may exhibit elements of patriarchal bias, this living essence carries no such bias. It is essential to study the

dakinl in her own context to understand the power and importance of this symbol for the authentic preservation of the yogic traditions of Tibet. Vajrayana Buddhism places emphasis upon oral instruction in the gurudisciple relationship, preservation of texts and teachings, and solitary practice as a way to safeguard these meditation and symbolic traditions. These aspects form the matrix of the study of the dakinl. SymBoQsm andSuBj'activity: The Feminine PrincipCe What is the significance of the gender of the dakinl? This is a central enigma of her manifestation, and

considerations of this question will arise throughout the chapters that follow. In previous interpretations of the dakinl, such as those influenced by Jungian psychology and by feminism, her gender has been the predominant factor. In the Jungian versions, her female gender has been abstracted, essentialized, and androcentrized. Feminist materials reacted to previous substantializing of gender issues even while they perpetuated them, causing reactive interpretations that also focus unduly on the dakinl's gender. It is clear that neither of these two general paradigms effectively addresses the

dakinl in her Tibetan context. When we deal with the dakinl as a religious symbol, her gender becomes more complex and multivalent. On an ultimate level, the dakinl is beyond gender altogether. As Janice Willis wrote, " 'she' is not 'female.' Though the dakinl assuredly appears most often in female form (whether as a female deity, or a female human being), this is but one of the myriad of ways Absolute Insight chooses to make manifest its facticity."87 "She" is in essence the vast and limitless expanse of emptiness, the lack of inherent existence of all phenomena expressed symbolically as space, that which

cannot be symbolized. But in the true Tibetan Vajrayana sense, "she" manifests in a female-gendered form on various levels. She also manifests in meditation phenomena that have no gendered form, such as in deity yoga, in the subtle-body experience of vital breath in the energetic channels, and in the experience of transmission from a tantric guru. The dakinl is, from this perspective, more than a singular symbol and more than a feminine deity. She represents a kind of "feminine principle,"88 a domain of spiritual experience beyond conventional, social, or psychological meanings of gender. This domain of the feminine principle permeates many levels of Tibetan Buddhist practice and understanding, each integrated in some way with the others. While the feminine principle takes a feminine form, ultimately there is nothing feminine about it. Additionally, because the term refers to emptiness, the absence of

inherent existence of any kind, either ordinary or divine, the word principle does not really apply either. Yet understanding the dakinl in this way is challenged most by the claim, central to Tibetan interpretation, that all human women are finally an expression of the dakinl. This creates a delicate situation that has often been misinterpreted. When Tibetans speak of all women as expressions of the dakinl, it is to indicate a sacred outlook concerning gender. This statement is not an invitation to make the dakinl and her realm a feminist bastion. As a young Nyingma lama, Ven. Tsoknyi Rinpoche, explained

to me in a kind of epiphany, "Women are part of the dakinl—dakinls are not part of women!"89 And, he continued, men are also emanations from the ultimate masculine principle. From the point of view of sacred outlook, human women are the display that emptiness takes when it expresses itself in form. Taking the form at face value in a substantial way causes the observer to miss the essential nature of the form. That is why the dakinl is a symbol. When we see the symbolic nature of the dakinl, there is fresh insight about the nature of all phenomena. For these reasons, I have chosen throughout my book to speak

of the "feminine," not of the "female." The Tibetan point of view, as I understand it, is that the English word female is embedded in substantiality, in inherent existence, in ego, in affirmative personal identity. When dakinls are spoken of as "female," mistakes can be made in interpretation. In the introduction to Mandarava's sacred biography, Janet Gyatso emphasized the femaleness of the great dakinl, proclaiming that "her female gender has a great significance of its own," and that she was a "female heroine in

her own right."90 Her interpretation of Mandarava emphasized the "feminist themes" of the work, the subversion of patriarchy, kinship structures, marriage, and power relationships. This prompted a preface with a disclaimer by the gifted American translator, herself a devout practitioner, who wrote, "I feel I must mention that the views and comparisons presented in the introduction that follows do not completely reflect my views and reasons for translating this precious revelation treasure. The basis for the difference of opinion centers around the interpretation of the feminine principle and how it pertains to the path of Vajrayana Buddhism."91 In our conversations, the translator expressed her opinion that Gyatso misunderstood the fundamental qualities of Mandarava's dakinl manifestation. The dakinl's depiction in feminine form has symbolic power in the meanings that she reveals, for the dakinl is the symbol of tantric wisdom in the nonconceptual sense. Specifically, she is the inner spiritual subjectivity of the tantric practitioner herself or himself, the

knowing dimension of experience. This subjectivity is not the personal, identity-oriented subjectivity that is discussed in feminism, psychology, phenomenology, or even postmodernism, for that matter. It is "subjectless subjectivity," an experience of the nature of mind itself, when mind is understood as no object of any kind. But this subjectless subjectivity is not adverse to contents. According to Anuttara-yoga-yana, all phenomena of gendered human life arise from the vast space of this subjectivity—and every aspect is seen to be a vividly clear, luminously empty symbol of mind's

nature. Spiritual subjectivity accessed in tantric practice sees ordinary phenomena in a transformed way, as the dance of emptiness. The subjective voice is often a feminine voice,92 and for the tantric practitioner the dakinl is the inner catalyst, protagonist, and witness of the spiritual journey. Representing the inner experience of the practitioner, she joins the guru to the disciple, the disciple to the practice, and the practice to its fulfillment. At the same time, the dakinl is the "other." As an outside awakened reality that interrupts the workings of conventional mind, she is often

perceived as dangerous because she threatens the ego structure and its conventions and serves as a constant reminder from the lineages of realized teachers. She acts outside the conventional, conceptual mind and has therefore the haunting quality of a marginal, liminal figure.93 Simultaneously the dakinl is more intimate than the tongue or the eyeballs and yet is feared as the "other," the unknown. Like the nature of mind in the Mahamudra tradition, she is too close to be recognized, too

profound to fathom, too easy to believe, and too excellent to accommodate.94 This is one reason that she is not immediately recognized by the most realized practitioners even when she is consistently present. The dakinl is the most potent realized essence of every being, the inner awakening, and the gift of the Buddha. The encounter with the dakinl is the encounter with the spiritual treasury of Buddhism, the experience of the ultimate nature of the mind in its dynamic expression as a constantly moving sky-dancing woman. She represents the realization of this nature, as well as the means through which the nature is realized.