Gyalwang Karmapa Gives Two Short Teachings: The Sutra in Three Sections and King of Aspirations: The Noble Aspiration for Excellent Conduct

The Sutra in Three Sections

During the first session His Holiness gave a short teaching on this prayer, before it was recited as part of the thirteenth section–Confession of Wrongdoing–of the Twenty Branch Monlam.

This prayer is used particularly for confession and purification following transgressions against vows, especially downfalls of the bodhisattva vow.

There is a story which tells how a group of monks, thirty-five in all, killed a child by accident one day, when they were on their alms round.

In their horror at taking a life, they went to one of the Buddha’s close disciples, Upali, and asked him to ask the Buddha for a method to confess and purify the deed.

The Buddha responded by speaking this sutra.

As he did so, light radiated from his body and thirty four other buddhas appeared around him.

The monks prostrated, took refuge, made offerings, confessed their misdeed and their vows were restored.

The Gyalwang Karmapa began by recounting how since beginningless time we have all taken countless births, during which time we had committed innumerable misdeeds.

In fact we commit more unvirtuous acts than virtuous ones, because of our habituation to unvirtue. If we do not confess these misdeeds, they will increase.

His Holiness used the analogy of a loan. You start by borrowing 100 rupees, but then, if you don’t pay it back immediately, the debt accumulates interest so now you have to pay back 200 rupees, then 500 rupees and so on

The heaviest misdeeds are violations of the three vows, because of the power of the vow.

If you have vowed to not do something and then do it, the fault you incur is greater than if you do not hold the vow.

Within the Mahayana tradition, the most powerful method for purification is reciting the Sutra in Three Sections.

This has the power to clear even heinous deeds.

When you do this practice, by reciting the Sutra in Three Sections over and over again, you must also invoke the four powers. First we have to have regret.

We can’t even remember all the misdeeds we have done in this lifetime, let alone previous lives, but the omniscient buddhas and bodhisattvas can be our witness.

We have to confess in front of them, for all time.

Secondly we need the power of resolve. Without resolve we cannot purify them.

Even though we know that in the future we may make the same mistake again, at the time of confession we need a strong resolve not to commit the misdeed or downfall again.

If we do repeat that misdeed, we need to confess and purify again.

King of Aspirations: The Noble Aspiration for Excellent Conduct

Also known as the Samantabhadra prayer, it comes from the Gandavyuha Sutra and is recited in the third session on the first and second day of the Kagyu Monlam.

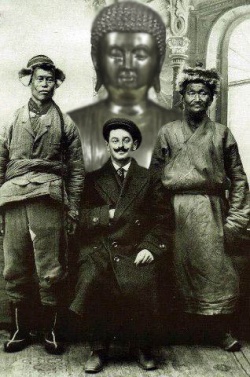

The Gyalwang Karmapa first reminded people how, when Kalu Rinpoche first established the Kagyu Monlam in Bodhgaya in 1983, the recitation of this prayer was the primary practice. The aim each year was to offer 100,000 recitations of the prayer.

In order to develop the path of liberation in our beings, we need to accumulate merit and remove obscurations.

Without these, it is impossible to develop realization.

Both aspects are covered in the Seven Branch prayer, and The King of Aspirations, according to scholars, is the clearest source for it.

As His Holiness explained, the Seven Branch Prayer is like the main body of our practice.

Although it may appear easy, that is deceptive; in fact this is the practice of all the bodhisattvas of the ten directions.

Within the Seven Branch Prayer, four branches – prostrations, making offerings, requesting the buddhas to turn the wheel of dharma and requesting them not to pass into nirvana- are for the accumulation of merit.

The branch of confession is for purification.

The branch of rejoicing can increase our merit.

The branch of dedication ensures that the merit is not wasted but increases. Thus, the practice of the Seven Branch Prayer completely covers both the accumulation of merit and purification of obstacles.

In addition the antidotes for all of the main afflictions are contained in it:

Prostrations are the antidote to pride.

Offering is the antidote to lack of generosity.

Confession is the antidote for general obscurations.

Rejoicing is the antidote to envy.

The request to turn the wheel of dharma is the antidote to ignorance.

Dedication is the antidote to wrong views.

Having explained the importance of this prayer, His Holiness then warned everybody of the danger of reciting prayers and mantras automatically, a habit most people have fallen into at one time or another.

All the teachers of the past, he said, have told us we need to be conscious of the meaning of the words when we recite them.

His Holiness drew on his own experience as a child:

When I was young, I hadn’t looked at many texts.

Had memorised them but didn’t understand the meaning. Teachers would tell me to think about the meaning. I took an interest and thought about this.

If you don’t have anything to think about, think about compassion, love for others, benefit to others. That’s what I thought at that time.

I memorised many things, and could recite texts, but my teachers told me that I should think about it…..

If your body is sitting in the row at the puja, but your mind is thinking about going to the market, watching TV or playing football, that is not what you should be thinking about.

As a consequence, the distance between what your mouth says and your Dharma practice will grow wider and wider until finally your mind will be completely separated from Dharma practice.

Any Dharma activities that you carry out will be ineffective.

There are some old people, he said, referring to a common Tibetan practice, which spend the whole day reciting Om Mani Padme Hum.

But their mind is elsewhere.

They recite the mantra faster and faster, and the pronunciation becomes less clear.

What they are mouthing has become separated from the meaning.

As the Tibetan saying goes:

There’s more benefit in thinking about virtue than reciting man is without thinking.

Please everyone keep that in mind, the Karmapa urged, as the chant masters took their cue and began reciting the opening lines of The King of Aspirations.