Hidden Tibet

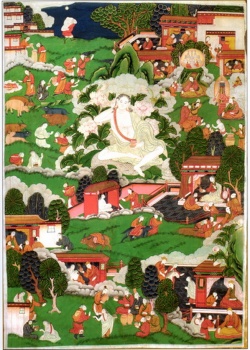

The Yarlung Dynasty ruled presumably from 95 BC to 846 AD on the southeast of the Tibetan Plateau, including areas of Yarlung, Nyangpo, Kongpo and Powo. The dynasty had forty-two kings.4

Their biographies include a number of details about supernatural events: communication with heaven, supernatural birth, etc. Some of these recorded details overlap with episodes of biographies of medieval Mongol khans and princes, probably not just because of mutual borrowing,

but also due to similarity in mentality of people who later formed the Tibetan-Mongolian civilization. In Europe, the first mention of the state of the Yarlung Dynasty was in the “Geography” by Claudius Ptolemy (about 87–165 AD).

The country was designated as “Batai” (from Tibetan “Bod”).

Early history of the Yarlung Dynasty is largely known from ancient Tibetan folklore and includes many myths.

The scientific community still debates the question of who among these kings was real, and who was mythical. But it is clear that the Yarlung Dynasty, probably dating back to the Bronze and Iron Ages, played a crucial role in the formation of the Tibetan people.

According to Tibetan folklore, Nyatri Tsenpo and the six kings that followed returned to heaven by a “sky rope” after their death, so their graves are unknown. The tomb of the eighth king is located in Kongpo in Ü-Tsang.

According to legend, he accidentally cut the “sky rope” and was unable to climb to heaven.5 This king was called Digum Tsenpo.

Sagan Setsen, Mongolian chronicler, traced the line of great khans of Mongolia to the Yarlung Dynasty.

He wrote that the youngest son of the king Jati Tsenpo, following his father’s assassination by a minister, fled to the area of the Bede people, who lived near the Baikal Lake and the Burkhan Khaldun Mountain.

A highly developed civilization evolved during the Yarlung Dynasty, with its main foundations being agriculture and animal husbandry.6

The population was divided into two main groups: farmers and urban dwellers (tonde), and pastoralists and semi-nomads (dogde). The territory of the state expanded. Kings Tagri Nyensig

and Namri Songtsen (570–620) fought for the unification of Tibetans into a single state.

The latter, according to legend, had a hundred thousand strong army, which reached north to the territory of the Turki and south into Central India. During his reign there were some revolts.

Namri Songtsen moved the capital from the valley of the Yarlung to the Kyichu valley, forming the Rasa settlement.

Subsequent rulers built a royal castle on the mountain Marpori and the settlement was renamed Lhasa (Land of Deities).

In the 7th century AD the Tibetan state came onto the world scene, briefly becoming one of the main powers operating in Central Asia. The great king Songtsen Gampo, the son of Namri Songtsen, was born in year 613 (or 617).

He was born shortly before the founding of the Tang State, which was created in 618 by Emperor Li Yuan (era name:

U-de).7 By this time, the Tibetan state stretched to the Thangla Ridge in the north, to the Himalayas in the south, to Mount Kailash in the west, and to the Drichu River (upper Yangtze) in the east.8 [

[Songtsen Gampo’s]] goal was the strengthening of statehood.

He supervised development of a system of land tenure and land use, creation of state funds for public lands, oversaw division of the country into six provinces that were led by set khonpons (governor-generals), conducted surveying and distributing of land, developed new legislation, created a new army, etc.

Writing was introduced in Tibet during the reign of Songtsen Gampo. Actually, according to the conclusion of J.N. Roerich, there were five attempts to introduce writing in Tibet.9 But the conventional system was developed by Thönmi Sambhota.

In 632, Songtsen Gampo sent him to India, where the Tibetan minister studied writing and grammar from the Indian pandits (scholars).

Upon his return to Tibet, he reworked the fifty Indian letters into thirty Tibetan consonants and four Tibetan vowels.

The basis of the alphabet was formed from the Indian scripts Brahmi and Gupta 10 with the framework of the case system being based on the Sanskrit system.

11 The previously used Tibetan system of grammar, which arose from the system of the Zhangzhung country, contained many awkward parts and forms of sentences.

Thönmi greatly reduced their numbers and made grammar much more convenient.

He developed a written language that became the same for all Tibetans, regardless of tribal differences in spoken language.

Songtsen Gampo combined the internal strengthening of the state with an active foreign policy aimed at the integration of the Tibetan and Tibetan Burman tribes, i.e. intending to unite them within natural national boundaries.

Military force was used to induce obedience amongst the Dokpa people (ancestors of modern Goloks) inhabiting the Machu River valley and to the south, the Panaca tribes that lived near the Kokonor Lake (area of Amdo) and in east Tsaidam, and the Horpa people that lived north of the Thangla Ridge.12

Integration of Qiang, Sumpa, Asha and other Tibetan tribes from the north-east began in the first half of the 7th century.

In 634, the Tibetans attacked the Dangsyan13 (ancestors of the Tangut) for the first time, when the latter were dependent on Tuguhun, a tribal State of Xianbi, who were the probable ancestors of the Mongols.14

This state occupied part of the modern Chinese provinces of Gansu, Qinghai, Sichuan and Xinjiang-Uighur Autonomous Region.

Seven years before that event took place, recently formed Chinese Tang State (618) sent ambassadors to Tuguhun in order to secure the Tang border area from attacks. However, the Khan of Tuguhun did not trust the Chinese.

He proposed a contract “he qin” (“for peace and kinship”): to arrange for a Tang princess to be sent for his son to marry. In the year of attacks on the Dansyan, Tibetans also sent an embassy to the Tang State.

The Chinese embassy, headed by Feng Dejia arrived to Lhasa in response. Tibetans, knowing the relationships between Tuguhun and Tang, also asked for a Tang princess for their monarch.

However, the Chinese fought with the Xianbi and the Turkic people, but not with the Tibetans, thus saw no point to concluding a peace treaty. Hence, the princesses had been sent to Tuguhun and the Turki, and not to Tibet.

According to the “Red Annals” chronicles, the Tibetan king’s response was a promise to send an army to take the princess by force, and to capture the Tang State.

On the 12th September 638, Tibetan troops invaded a village in the Xuizhou District that was inhabited by the Dangsyan (in modern Sichuan). At the same time, a Tibetan ambassador arrived at Chang’an (the capital of the Tang State) and threatened to attack the Chinese land.

Now a reason for the treaty emerged. In December 640, the Tibetan dignitary Tontsen Yulsung brought five thousand liangs of silver and hundreds of gold objects to Chang’an. In March of the next year, he went to Lhasa, accompanied .

13 The names of many ancient tribes, cities, states, names of people, etc. have only reached us in the Chinese form: from Chinese chronicles. Non-Chinese (i.e. titles and names in original language) of these forms are unknown, because written sources have not been preserved, languages did not have script, and so on.

by the Chinese princess Wencheng. The journey to Lhasa took several years and Wencheng became wife of Songtsen Gampo only in 646. For about five years, the king did not rule the country; instead the ruler was Gungsong Guntsen,

the son of Songtsen Gampo from his Tibetan wife Mongsa Tricham (he had no other sons).

According to custom, he ascended the throne after having reached thirteen years of age. But at eighteen, he died, and Songtsen Gampo was again obliged to take the throne.

It is believed that Songtsen Gampo temporarily lost power in the fight with his influential adviser, but managed to defeat him in the end.

Wencheng brought a statue of the Buddha (Shakyamuni Jowo) with her, as well as more than ten thousand bales of embroidered brocade, lots of boxes of Chinese classics, various utensils and books on different technologies.

She helped Buddhist monks from Yutian (Hotan) and other places to come to Tibet for the construction of Buddhist monasteries and also for the translation of the Canon.15

But the first wife of the king was the Nepalese princess Bhrikuti, and she brought with her images of Maitreya, Tara, and a statue of the Buddha at the age of eight years old.16

Songtsen Gampo congratulated the Tang Emperor Li Shimin (era name: Zhenguan) with a victory in the east of Liaoning Province.

Following the etiquette of his time, he pointed out that the emperor had won all sides of the Middle Kingdom, and expressed a desire to help suppress any riots when they arose against him.

This message speaks of allied relations between the two monarchs. But some historians use this to make a strange conclusion: “These facts prove that Songtsen Gampo himself regarded Tibet as being under the local administration of the Tang Dynasty”.17

The marriage of the Tibetan king to the Chinese and Nepalese princesses was an important political act.

However, most important was the spiritual contribution of the two princesses towards the development of Buddhism in Tibet.

In addition, it significantly strengthened the connection of Tibet with the two countries.

This does not mean that Tibet became subordinate to China or Nepal, but rather thanks to China, Tibetans came across paper and ink, perhaps also a millstone, a few other crafts, and they adopted certain features of the Chinese administrative system.

However, it is wrong to link this with the beginning of Tibetan agriculture, as some Chinese authors do.18

In those same years, Tibetans won the upper part of Burma, and in 640 Nepal, where they remained for several years.19 In Nepal, a column was erected, on which the inscription tribute to the Tibetan king was engraved. Tibetan migrants settled in

15 Briefly on Tibet... 16 King Songtsen Gampo... 17 Tiang, J. The Administrative System... 18 See in:

Nepal and gave rise to the Nepalese tribes Tsang, Lama, Sherpa and Tamang.

In 643, the king of Zhangzhung became the vassal of the king of Tibet. In 645, the Chinese emperor sent a mission to the court of King Harsha in one of the states of North India.

By the time the mission arrived, the king had died, and his minister Arjuna (who was intolerant of Buddhism) took the throne.

The Chinese who arrived were killed on his orders. Only a few people along with the head of the mission managed to survive.

They fled to Nepal and asked Songtsen Gampo for help, and in response he sent an army of Nepalese and Tibetans into India.

The Chinese emperor was so grateful to Songtsen Gampo that he bequeathed to place a statue of the Tibetan king by his grave. That was an honour, but with a trick: usually statues at the tomb of the Emperor were those of his high officials and ministers.

In 649, Songtsen Gampo died of an infectious disease that caused a fever.20

According to legend, he dissolved into a small wooden statue of the Buddha that was brought from Nepal and placed inside the statue of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara installed in Jokhang, the main temple of Tibet in Lhasa.

After Songtsen Gampo’s death, the throne passed to his grandson Mangsong Mangtsen. However, the actual power belonged to Tontsen Yulsung,

the member of an ancient Ghar clan.

The clan held onto this power up until 698. In 655, shortly after the death of Songtsen Gampo, Tontsen Yulsun put in a claim to the Tuguhun state as an ancient frontier of the land of Tibet.

Tuguhun began to ask for help from the Tang emperor, but was turned down.21

The Tuguhun dignitary named Tohegui, who was a relative of the ruling dynasty, fled to the Tibetans, and informed them about this.

Then in 663, the Tibetans took Tuguhun, defeating the army of the country. In the years 667–670, the Tibetans began to destroy chimi.

These counties were vassals, but not part of the Tang state. They were created by the Chinese on the lands of the Qiang who became their subordinates.

In 670, the Tibetans forged an alliance with the Turkis and invaded the Tarim River valley.

The Chinese response was to send a hundred thousand strong army under the command of Xue Zhengui in August 670, which invaded the Kokonor area.

The Tibetan army under the command of Tidin Ghar defeated the Chinese at the Bukhain Gol River.

At the same time, the Tibetans developed an offensive in the west.

In 656, they captured Wahan and placed Bolor under their control.

Before 670, Hotan and Kashgar were recaptured from the Chinese, and by the end of the 670s Tibet had control of almost the entire Tarim basin and the mountains to the south-west of it.

The Chinese lost their outposts in East Turkestan. This forced them to move their attention to Tibet despite the fact that the Tibetans defeated the Chinese

20Shakabpa,

army at Kokonor in the summer of 678. After that, the war between Tibet and the Tang State temporarily halted in connection with the death of the rulers of both countries and subsequent domestic events.

In 687, the Tibetans attacked the city of Kucha (in modern Xinjiang). The Chinese sent an army to the aid of their vassals, which was defeated by the Tibetans in the summer of 689. In 692, a new Tang army marched out, led by Wang Xiaoze.

Soon the Tibetans left Kashgaria. It is not known, whether it was caused by the Chinese victory or the Tibetan king Duisong Mangje who ordered to withdraw.22

The latter could have been useful to him to fight the [[Ghar clan, which held power through external victories.

Now the king blamed Ghar for the defeat in the war. In the next two years, Tibetans suffered further defeats from the Chinese at the northeastern and western borders, where the Chinese had allied with the Turkis.

However, in 695, the Tibetans struck the Chinese with a serious blow in the direction of Lanzhou, and then they went on to offer a peace treaty, threatening to cut off the Chinese connection with the Western boundary if not accepted.

Knowing about the internal political struggle in Tibet, the Chinese began to drag out the negotiations, hoping for the fall of the Ghar clan that was so successful in fighting them.

Indeed, in 698 Dusong Mangje attacked the Ghar, captured about 2,000 people from their clan, and executed them. Tidin Tsendo Ghar tried to resist, but was defeated and ended up committing suicide, while his brother and his sons fled to China.

However, restoring the power of the real king did not change Tibet’s foreign policy. In the years 700 and 701, Tibetans resumed hostilities in Lanzhou and in the north-east.

During the next few years fighting was interspersed with negotiations. In 703, an uprising against the Tibetans flared up in Nepal and India.

Dusong Mangje died during their suppression in 704, soon followed by the (Tang Wu Hou, who ruled China for a long time.

New negotiations in 706 were completed with a “vow to unite for many years under the era name of Shen-long,” and border demarcation drawn between the two states, —the Tibetan Kingdom and the Tang Empire.

In 707, the Chinese agreed to a treaty “he qin” (“on peace and kinship”), and in 710, Princess Jincheng was sent to Tibet.23

Tang Emperor personally accompanied her for some part of the way. The monarch of Tibet had been given the Hesi juqu lands (to the east of the Kokonor Lake and on both banks of the upper reaches of the Yellow River) as the dowry.

In 713, Jincheng became the wife of King Tride Tsugten (nicknamed Me Agtsom).

In 714, the Tibetans advanced towards Lintao and Lanzhou, and in 716 and 717 they moved towards the borders of Tang in the modern provinces of Sichuan and Gansu. In the west they were acting in alliance with the Arab commander

While introducing Islam in Central Asia, Kuteiba’s warriors barbarically destroyed “pagan” cultures. However, the Tibetans did not understand the threat of the expansion of the Arab Caliphate.

The Arabs were considered to be one of the weaker nations, which could have either been allies or adversaries.

Tibetan support did not matter much, and in 715, Tang forces, staffed by Western Turkic people, defeated the Arabs in Ferghana.

Later, in 736–737, Tibetans together with the Turkic people (Turgesh Khanate) fought with their former Arab allies, who sought to capture Tashkent and Ferghana. The Arabs tried to establish contacts with the Chinese, but were unable to come to an agreement.

As well as fighting, Tride Tsugten tried to make peace with the Tang State in 716, 718 and 719.

However, these attempts were unsuccessful.

In 724, the resumption of the war, which lasted until 729, and the alternation of victories and defeats led to a situation which the Chinese public figure Zhang Yue determined “as the existence of approximate equality in the number of victories and defeats”.

24 Both sides accused their border chiefs of aggressive actions and assured their own peaceful intentions.

In 730, after 60 years of war between the Tang Empire and Tibet, peace was eventually established.

An important role in this was played by a Tibetan ambassador, who spoke fluent Chinese, and also by the Chinese wife of the Tibetan king.

The parties agreed that the border between both countries would be the Chilin Ridge (identified with the mountains of Ulan-Shara-Dava to the east of Xining, modern Qinghai Province) and the Gansunlin Ridge (Sunpan County, Sichuan Province).

It is believed that the border demarcation was not completed due to the fact that war resumed again after seven years.

In 736, the Tibetans attacked Gilgit in Kashmir. In 737, the Chinese attacked the Tibetans in the Kokonor area. After that, clashes began to expand, and the border guide-posts on the Chilin ridge were destroyed. Jincheng died in 741.

Tibetans resumed their raids on border areas of Tang, seizing bread which was made by the Chinese. They captured the Chinese town of Xipa and held it until 748.25

In 747–750, the Chinese sent a large army to the west and were able to knock the Tibetans out of Gilgit, Xipa, the principalities of the Tarim Basin.

In 751, Arabs defeated the Chinese army at the Talas River.26 In 751–752, the Tibetans conquered the Nanzhao State in the south-east (modern Yunnan Province).

In 750, they entered an agreement with the Thai.

The Thai ruler was called the “younger brother” of the king of Tibet.

Tride Tsugten died soon after, and at the same time, An Lushan’s rebellion broke out in China. The new Tibetan king Trisong Deutsen used the temporary weakening of his neighbors and conquered large territories in the modern Chinese provinces of Gansu and Sichuan.

He also restored the influence of Tibet in the Western region.

Together with the Uighurs, Tibetans offered Chinese assistance in quelling the rebellion, demanding the treaty “on peace and kinship” in return. The Chinese agreed to meet the demands of the Uighurs, but not the Tibetans.

The king of Tibet used this refusal as a pretext for war with the Tang Empire.

Two armies were sent to the Chinese capital. They were under the command of generals Shanchim Gyeltseg Shulteng and Taktra Lukong.

There was a great battle. Tang forces were defeated with the emperor fleeing.

On the 18th November 763, Tibetan troops occupied the Tang capital, city of Chang’an, and the Tibetans put Li Chenhung (grandson of Li Zhi) on the Chinese throne.

The Li Chenhung government announced his rule with a new era name, Da-shu.

The Tibetan king rewarded both generals in the form of being released from criminal penalties (including death) for any misconduct, except for treason to the king.

A stele was erected to commemorate the victory.

Amongst other engravings, there was an inscription stating that Trisong Deutsen conquered many Tang fortresses, and the Tang Emperor and his subjects were asked to pay tribute to the Tibetan king with 50,000 pieces of silk, but the next emperor refused to pay tribute, so the Tibetans sent an army, defeated the Chinese Emperor and caused him to flee from the capital.27

After fifteen days the Tibetan troops left the capital of Tang, but they furthered their military success in subsequent years. By 781, Hami, Dunhuang District, Lanzhou City, Ganzhou, Suzhou were all in Tibetan hands.

The Tang Empire had lost its most important road to the west. In 783, a peace treaty was signed between Tibet and Tang in Qingshui.

This treaty clearly delineated the new boundaries between the two countries, with the Chinese having made major territorial concessions. According to current Chinese estimates, the “Helanshan area north of the Yellow River stood out as a neutral land.

The border line was stretched to the south of the Yellow River along the mountains Liupanshan, in [[Longyou], along the rivers of Minjiang and Daduhe and south to the Moso and all Man’ (modern district of Lijiang, Yunnan Province). Everything to the east of this border line was 27 Ngabo, 1988. Trisong Deutsen owned by Tang, to the west by Tibet”.28

Thus, the Tang Empire recognized the de facto domination of Tibetans over the area of Helong and the lost control of the Western region.

After signing the treaty, Tibetans helped the Chinese to suppress revolt led by the dignitary Zhu Zi. For this the Chinese promised to give the Tibetans control over districts Anxi and Beiting, but they did not keep their promise. In response,

the Tibetans attacked the Tang fortress in Ordos, and in 787 they approached Chang'an.

In subsequent years, the Tibetans also fought with the Uighurs and Arabs, and consequently, in 791, the Tibetans captured a significant part of East Turkestan.

At the end of the 8th and beginning of the 9th century the Tibetan Kingdom was at the peak of its power.

It is believed that the Shah of Kabul became its vassal, and the Tibetans controlled part of the Pamirs and Kashmir.29

In the north, the Tibetan army reached the Amu Darya River.30

It was also during this period that Tibetan documents started to utilise the term of Bod Chenpo (“Great Tibet”).

The Tang historical chronicle “Ju Tang shu”, Chapter 196B, reads as follows:

“The Tibetans established their kingdom on our western border many years ago; as silkworms, they bit into [the lands] of their barbarian neighbours so as to enlarge their territory.

During Gao-zong their territory was ten thousand li, and they competed with us in superiority: in more recent times, there is nobody stronger than them”.31

But by the end of the 8th century, the power of Tibet began to show cracks.

In 794, the ruler of the Nanzhao State refused to obey Tibet and became a vassal of the Tang Emperor.

In the north Tibetans were pressed by Uighur Khanate, whose ruler signed a treaty “on peace and kinship” with the Tang Dynasty.

After the death of Trisong Deutsen the throne was taken by his second son Mune Tsenpo.

Seeing the inequality between his subjects and the poverty among his peasants, Mune Tsenpo decided to eliminate the division between rich and poor, so a decree was issued on equalising land use. After some time the king asked about the results of the reform.

He learned that the poor had become poorer and the rich richer. Frustrated, he turned for advice to the Buddhist preacher Padmasambhava, who advised him that the king could not forcibly remove the inequality between rich and poor.32

Having reigned for only a year, Mune Tsenpo was poisoned, and died, thus ending the attempt of egalitarian redistribution, the only one in the history of independent Tibet.

Political instability pushed the Tibetan king, Tri Ralpachen, to enter into negotiations with the Tang Empire. The Treaty was signed in 821 in the suburbs of Chang'an and, in 822, in the suburbs of Lhasa.

The text was engraved on four columns, which were then erected in Lhasa, Chang'an and at the border on both sides.33 Both monarchs were called zhu (“sovereign”) in the Chinese text.

The Chinese monarch was named as senior (ju, maternal uncle), and the Tibetan junior (sheng, nephew).

During this time, both states were considered to be independent and equal:

“The great king of Tibet, the Divine Manifestation, the bTsan-po Tsenpo, and the great king of China, the Chinese ruler Hwang Te, Nephew and Uncle, having consulted about the alliance of their dominions have made the great treaty and ratified the agreement... Both Tibet and China shall keep the country and frontiers of which they now are in possession.

The whole region to the east of that being the country of Great China and the whole region to the west being assuredly the country of Great Tibet, from either side of the frontier there shall be no warfare, no hostile invasions and no seizure of territory...

Now that the dominions are allied and a great treaty of peace has been made in this way, since it is necessary also to continue communication of pleasant messages between Nephew and Uncle, envoys setting out of either side shall follow the old established route...

According to close and friendly relationship between Nephew and Uncle the customary courtesy and respect shall be practiced. Between the two countries, no smoke or dust shall appear.

Nor even a word of sudden alarm or of enmity shall be spoken, and from those who guard the frontier upwards, all shall live at ease without suspicion or fear, their land being their land and their bed their bed...

And in order that this agreement – establishing a great era when Tibetans shall be happy in Tibet and Chinese shall be happy in China – shall never be changed, the Three Jewels, the body of saints, the sun and the moon, planets and stars have been invoked as witnesses”.34

The website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC summed up the above as follows: “Both sides of the agreement officially declared their historical 33 Shakabpa, 1988. 34

In: Van Walt, 1987, p.1–2. Tri kinship and agreed that in future they will consider themselves as nationals of one country”.35 The years following this treaty were marked by the strengthening of Buddhism in Tibet, however it was briefly interrupted by an attempt to eradicate the religion by king Darma (see Chapter 5).

After his assassination in 842, the princes Ngadak Yumden and Ngadak Ösung began to fight for power. Yumden’s stronghold was in the Yarlung, Ösung’s in Lhasa. Ösung’s great-grandson (great-great-grandson of Darma) fled to Western Tibet (Purang), where he founded the Ngari Dynasty,

which was to rule the Guge Kingdom for many centuries after.

Ösung’s second grandson strengthened his position in Tsang. Warlords and major officials sided with this or that ruler, or declared their independence.

In 851, Dunhuang broke away from Tibet with a Tibetan governor of Chinese nationality, adopting Tang citizenship.

However, this was merely a formality. In fact, Dunhuang came under the authority of Beijing only under the Mongols.

In 860, a commander of Tibetan nationality in Sichuan deserted to Tang. Another Tibetan warlord was captured by the ruler of closely related people, the Tangut.

This ruler was beheaded and his head was sent to the Tang capital. Remaining Tibetan troops that were stationed outside from Tibet partly assimilated, and partly formed compact enclaves.

Thus, at the end of the 10th century, Tibetans were in control of a large area with its center in Lanzhou, whereas in the 11th century the Tibetan state was in the area of Kokonor,

with small enclaves in the upper reaches of the Yellow River.36

Some authors believe that the collapse of the great State of Tibet was facilitated by Buddhism, which led to internal strife.

The dynasty’s charisma was covered by Bon, which was partly superseded, but Buddhism had not yet taken its place fully.

However, there is no direct evidence of this. Different groups have used one or the other religion for political purposes.

A significant contribution towards the collapse of the country was likely the result of the high costs of running the military, and the lack of necessary resources to control a large area.

Small enclaves in northern Tibet forged an alliance with the Chinese and fought with the Tangut Empire (Chinese: Hsi Hsia), as well as fighting among themselves.

Gradually, these Tibetan territories came under Chinese rule, then under the authority of Tangut.

The Tibetans occupied an important place in the Tangut Empire.

Their language was the recognized language of Buddhism, they had their own Buddhist community, and Tibetans themselves were one of the major nations of the empire, together with the Tangut, Chinese and the Uighur. In the 10th century, spiritual and public powers of Tibet began to fuse.

Political life was flowing quietly, and Buddhism was developing and consolidating the 35 Briefly on Tibet: a historical sketch... 36

country. This led to the final formation of the Tibetan nation. Relations with Chinese states, that entered the arena of history after the Tang Empire, were weak.

There was next to no exchange between the Tibetan and the Chinese governments.

During the time of the Five Dynasties (907–960) and during the Song Dynasty (960–1279) relations of Tibet and China were limited to border skirmishes, trade and formal politeness.

This included the sending and receiving of gifts and titles, which has sometimes been incorrectly interpreted as subordination to the central Chinese Government or being part of China.

By 1206 Genghis Khan united the Mongol tribes under his rule and led an active policy of conquest.

He forced the Uighurs and the Turkic Karluks, with whom Tibetans had long-standing relationships, to obey, and so the Mongol Empire expanded rapidly. In 1206 or 1207 the Tibetans sent a mission to Genghis Khan.

The mission included secular and religious representatives, who expressed submissiveness, and presented him with rich gifts.37 Like other subjugated people, they began to pay tribute. This saved Tibet from a Mongol invasion.

In 1227, the Mongols conquered the Tangut Empire, with its khan being executed. Genghis Khan died at the capture of the capital city of Tangut.

After that, Tibetans ceased to pay tribute, and relations with the Mongols became strained.38 In 1240, Central Tibet was invaded by a thirty-thousand strong Mongol army, under the command of [[Leje] and Dorda Darkhan.

The army was sent by Prince Godan, who was the second son of Ugedei Khan, and the grandson of Genghis Khan.

The Mongols ended up reaching Phenyül, north of Lhasa, where a fight broke out and two monasteries were burned, killing the priest-ruler and five hundred monks.39

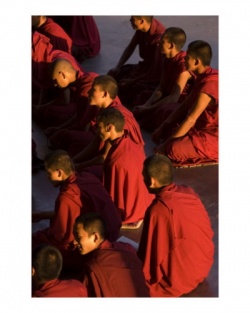

The Mongols did not go any further. Godan, however, did not forget about Tibet. He sent an invitation to Kunga Gyaltsen (Mongolian: Gunga Jaltsan), the head of the Buddhist Sakya sect, whose great scholarly knowledge led to him being called Sakya Pandita.

There are several versions of the reason for this invitation. The most plausible and generally accepted one states that Godan wanted to adopt the Buddhist religion from a great 37 Ssanang Ssetsen, 1829. 38 Shakabpa, 1988. 39 Shakabpa, 1988.

Lama, which he knew about from fighting with countries bordering with Tibet.

There were several reasons for choosing this particular religious sect.40 Mongolian society and pre-Buddhist faith were similar to Tibetan, they were attracted to Tantric Buddhism, the sect of Sakya followed old Buddhist traditions, and its Lamas were actively developing contacts with the political rulers. Such were the features of the emerging Tibetan-Mongolian civilization.

Godan wrote:41 “I, the most powerful and prosperous Prince Godan, wish to inform the Sakya Pandita, Kunga Gyaltsen, that we need a lama to advise my ignorant people on how to conduct themselves morally and spiritually.

I need someone to pray for the welfare of my deceased parents, to whom I am deeply grateful.

I have been pondering this problem for some time, and after much consideration, have decided that you are the only person suitable for the task. As you are the only lama I have chosen, I will not accept any excuse on account of your age or the rigors of the journey.

The Lord Buddha gave his life for all living beings. Would you not, therefore, be denying your faith if you tried to avoid this duty of yours?

It would, of course, be easy for me to send a large body of troops to bring you here; but in so doing, harm and unhappiness might be brought to many innocent living beings.

In the interest of the Buddhist faith and the welfare of all living creatures, I suggest that you come to us immediately. As a favor to you, I shall be very kind to those monks who are now living on the west side of the sun.

I send you presents of five shoes (ingots), a silken gown set with six thousand and two hundred pearls, vestments and shoes of silk, and twenty silken rolls of five different colors.

They are brought to you by my messengers, Dho Segon and Un Jho Kharma.

(Dated) The 30th day of the eighth month of the Dragon year (1244)”. Sakya Pandita went to Godan along with his two nephews, Lodö Gyaltsen, who was ten years old, and Chagna, who was six.

They arrived at Godan’s headquarters in 1245, but did not find him there, as the prince was at the grand khuraldai in Mongolia.

The meeting took place in 1247 near the city of Lanzhou. Godan built the Tulpe De monastery (which still exists) for Sakya Pandita. The Lama healed him from an unknown illness.

Godan gifted Sakya Pandita with authority over entire Tibet.

However, this did not mean that the Tibetan tribes were attached to the Mongol Empire and were now obliged to obey all of its administrative decrees.

Being empowered by Godan, Kunga Gyaltsen told the Tibetan rulers that he saw the spreading of Buddhism outside of Tibet as the main goal, and that this would 40 Bira, 1999 — in: Kychanov and Melnichenko, 2005. 41 In: Shakabpa, 1988, p.61–62.

help his country.42 He wrote that the prince was counting on the Tibetans for help in matters of religion, and that Mongols would help the Tibetans in worldly affairs.

Such were the foundations of the relations between the theocratic rulers of Tibet and the Mongol (later Manchu) khans, built on the principle of “spiritual priest – secular patron” (in Tibetan chos–yon, Chos stands for Dharma, the teachings of the Buddha; Yon for charity or reward).

That is, one teaches Dharma, and the other one responds with rewards of gifts.

The origins of this principle (in the form of “Lama—charity donator”) come from ancient India, where communities of Buddhist monks lived off charity, and where showing respect and feeding the monks was seen as a way of collecting spiritual merit for the layperson.

From the middle of the 9th century to the beginning of the 13th century, this formula was used in relation to monasteries and the local Tibetan population.43

Godan was a vassal of the Great Khan of the Mongols. Therefore, when Munke took the throne in 1251, he sent officials into Tibet in order to verify the census and to approve the property ownership of local secular and religious rulers.44 However, neither the imperial administration, nor the troops were ever sent to Tibet.

Kunga Gyaltsen died in 1251, and Godan also died very soon after. That same year, Kublai, grandson of Genghis Khan, led a campaign against Southern China as ordered by Munke, the Mongolian Great Khan.

The older nephew of Kunga Gyaltsen, Phagpa Lama, converted Kublai to Buddhism in 1253. The conditions of this conversion were described in different ways.

Some reported that Phagpa gave Kublai Buddhist initiations on the condition that he would consult with him on issues of Tibet and would not interfere in the affairs of Mongolia.

In addition, Kublai had agreed to perform ritual bows to his Lama during meditations,

although not in public. According to other sources, Kublai agreed to sit below Phagpa during meditation, exercise and taking vows,

whereas both would sit on one level when 42 Shakabpa, 1988. 43 Besprozvannykh, 2001, p.57. 44 Kychanov and Melnichenko, 2005.

managing public affairs. After this, Kublai Khan and twenty-five members of his entourage received Phagpa Lama’s initiation into Hevajra Tantra, the most important tantra of the Sakya sect. 45

Kublai had given Phagpa Lama a document to confirm the latter’s supreme authority over Tibet:46

“As a true believer in the Great Lord Buddha, the all-merciful and invincible ruler of the world, whose presence, like the sun, lights up every dark place, I have always shown special favor to the monks and monasteries in your country. Having faith in the Lord Buddha, I studied the teachings of your uncle, Sakya Pandita, and in the year of the Water-Ox (1253), I received your own teachings.

After studying under you, I have been encouraged to continue helping your monks and monasteries, and in return for what I have learned from your teachings, I must make you a gift. This letter, then, is my present.

It grants you authority over all Tibet, enabling you to protect the religious institutions and faith of your people and to propagate Lord Buddha’s teachings.

In addition, my respected tutor, I am presenting you with garments, a hat, and a gown, all studded with gold and pearls; a gold chair, umbrella, and cup; a sword with the hilt embedded with precious stones, four bars of silver and a bar of gold;

and a camel and two horses, complete with saddles. In this year of the Tiger, I will also present you with fifty-six bars of silver, two hundred cases of brick tea, and a hundred and fifty rolls of silk,

to enable you to build images of the deities. The monks and people in Tibet should be informed of what I am doing for them.

I hope they will not look for any other leader than you. The person who holds this letter of credentials should, in no way, exploit his people. Monks should refrain from quarreling among themselves and from indulging in violence.

They should live peacefully and happily together.

Those who know the teachings of the Lord Buddha should endeavor to spread them; those who do not know his teachings should try to learn all they can. <...> As I have elected to be your patron, you must make it your duty to carry out the teachings of the Lord Buddha.

By this letter, I have taken upon myself the sponsorship of your religion.

(Dated) The ninth day of the middle month of summer of the Wood-Tiger year (1254)”.

With this document, Kublai confirmed his relationship with the highest members of Sakya hierarchy to be of the principle of “priest – patron”.

In addition, he allowed all other sects to practice Buddhism in accordance with their traditions, and Phagpa Lama did not interfere in them. Sometimes this has been reported in an amusing way:

“In the thirteenth century, Emperor Kublai Khan created the first Grand Lama, who was to preside over all the other lamas as might a pope over his 45 The Mongols, 2009, p.17. 46 In:

bishops”.47 Or even funnier: “In the 13th century, Genghis Khan’s grandson Kublai Khan gave one of the prominent Buddhist teachers the title of Emperor’s teacher, or the Dalai Lama, and instructed him to control the Tibetan land”.48

In 1258, by order of Munke Khan, Kublai headquarters held a dispute between Buddhists and Taoists, and the latter lost. This strengthened the position of Buddhism in the Mongol Empire. Munke Khan perished in August 1259.

The throne of the Great Khan was then claimed by several descendants of Genghis:

brothers Hulagu, Kublai and Ariq Böke. Hulagu lived in the Middle East, and was occupied with strengthening his authority there. Kublai was in China, which was not yet fully conquered. Ariq Böke was elected as the Great Khan of Mongolia.

But the real contenders were Kublai and Ariq Böke. Kublai convened a congress of princes, who proclaimed him as the Great Khan.

He won in the ensuing civil war. Phagpa Lama announced Kublai to be the reincarnation of Manjushri, Bodhisattva of Wisdom.

Kublai Khan was a very gifted man indeed. Even in his youth, he was called “Setsen” (Mongolian: “Wise Man”).49 Later, he was titled in this way in Mongolian chronicles.

In 1265, for the first time after his departure from his homeland, Phagpa Lama arrived in Tibet. Then in 1267, he received a letter from Kublai Khan with an invitation to return to his court.

In Mongolia, he was met by the Khan’s wife and the eldest son, to oversee his travel to the capital. Upon his arrival to the Khan’s capital Khanbalik in 1268, Phagpa Lama brought to Kublai’s attention an alphabet developed by him for the Mongols, which was based on the Tibetan alphabet (so-called square script).

This script allowed him to transmit the phonetics of the Mongolian and Chinese languages. Kublai Khan was very pleased as he understood the importance of language in the preservation of ethnicity.

Kublai Khan then gave Phagpa Lama the title of “Prince of Indian Deities, Miraculous Divine Lord under the Sky and Above the Earth, Creator of the Script, Messenger of Peace throughout the World, Possessor of the Five Higher Sciences, Phagpa, the Imperial Preceptor”.50

In 1271, Kublai Khan followed the Chinese tradition and proclaimed a dynasty, the Yuan, which became his empire’s name. China (Southern Song State) at that time had not yet been conquered completely.

Phagpa Lama bestowed titles of Chakravartin (ideal world ruler that turns the Wheel of Dharma, i.e. helping Buddhism), and Dharmaraja (King of Dharma) to Kublai,

the title of Universal Monarch to Kublai’s grandfather, Genghis Khan. Phagpa Lama received the title of Master of the State, a jasper seal of ruler of Tibet and the Buddhist ruler of the empire.

Thus, the old relationships of “priest – patron” were confirmed. Lama was gifted with of a thousand 47 Parenti, M. Friendly feudalism... 48 Ovchinnikov, 2007, 2009. 49 Dalai Ch., 1977, p.324. 50 Shakabpa, 1988, p.68-69.

ingots of silver and fifty-nine thousand bales of silk. In 1274 he decided to return to Tibet.

Stimulated by deference towards his teacher, the Great Khan accompanied him on the road for a few months until they reached the bend of the Machu River (upper part of the Yellow River) in Amdo.

Then in 1276 Phagpa Lama returned to Sakya under the protection of the Mongolian detachment.

When the Mongols finally seized China in 1279, Phagpa Lama greeted Kublai Khan with gifts and a congratulatory letter. Then in 1280 Phagpa Lama died at the age of 46 years. It was said that he was poisoned by his entourage.

In order to investigate, Kublai sent to his two commanders along with a military detachment.

The commanders beheaded Ponchen Künga Sangpo, who was the main suspect in the poisoning. But the latter was apparently “framed” by the real perpetrator.

After finding out about the unfair verdict, Kublai Khan executed both commanders, and Phagpa Lama’s position was taken by his nephew Dharmapala.

But, after five years, Dharmapala died while travelling from Khanbalyk (Beijing) to Tibet. This provoked public unrest, which was then crushed by the Mongols.

Following that, each Yuan Emperor had a lama51, and hierarchs of the Sakya Khon family were appropriated the title of “baylan wang” and were given Mongol princesses for marriage by the Mongols.52

It was reported that around 1286 Kublai Khan was going to attack India and Nepal via Tibet 53, and that a Tibetan yogi Ugyen Senge, who was living in India at the time, sent a long religious poem to the Khan, asking him to abandon the campaign.

As it turns out Kublai Khan did not end up going against India and Nepal.

Also during the same period, a local ruler rebelled against the central authorities of Tibet, and mutiny was suppressed without the participation of the Mongols.

Thus, China became an integral part of Yuan, which, in turn was part of the Great Mongol Empire — the biggest country that ever existed in the world, which stretched from the Pacific Ocean to Europe.

Tibet, however, never became a part of the Empire, as it was not conquered, and never gave the oath of vassal fealty.

It was also not on the official list of territories of the Yuan Empire 54, and therefore did not fall under the Empire’s territorial administrative system.

The Yuan emperors’ relationship with religion was different than that of Chinese emperors, and the model of such a relationship was described in the Mongolian chronicle “Ten Laudable Laws”,

in which a theory of “two orders” was cited, that obviously reflected the views of Phagpa Lama on secular power.55 The theory was based on the views that all worldly creatures strive for secular and spiritual salvation,

51 Uspensky, 1996, p.40–51. 52 The Mongols, 2009, p.31. 53 Shakabpa, 1988. 54 Yuan shi, 1935 — in:

and that spiritual salvation can be found in the complete liberation from the suffering, while its secular counterpart’s salvation in the well-being. Both depended on the two orders, the religious and secular.

The religious was based on the Sutras and Tantra, while the secular was based on peace and tranquillity.

The Lama was responsible for the religious order, Ruler of the secular.

Thus, religion and the state depended on each other. Heads of state and religion were equal, but each had its own functions. The Lama corresponded to Buddha, the Ruler to Chakravartin.

These virtues appeared only once every period in history. In the 13th century these were Phagpa Lama and Kublai Khan. Obviously, this order was not observed exactly. Nevertheless, the Yuan emperors tried to follow it.

According to the theory developed by Phagpa Lama, the Mongolian emperors were regarded as heirs of the world’s Buddhist emperors, and not as heirs of any Chinese dynasty.

Both Genghis Khan and Kublai Khan were equated with Chakravartins of India and the holy Tibetan kings.

Meanwhile, Chinese scholars were developing a scheme allowing Kublai and his descendants to fit into a sequence of legitimate dynasties that ruled China (for details, see Chapter 11).

During Kublai Khan’s rule, a system of administrative management was developed, which went on to change very little until the last days of the Yuan Empire.56

Administrative agencies that ran the main country (Mongolia) were particularly well developed, while the agencies governing other areas were less effective, with their functions often duplicated, etc.

Due to the fact that the management of the Empire was weakly centralized, local authorities in distant lands were controlled only “ex post”.57 The Bureau of Imperial Cults was in charge of the religions, and it oversaw most of the religious institutions.

Five provinces had their own administrative centres, and a special Zongzhiyuan Office was established for Tibet, with Phagpa Lama becoming its first head.58

In 1284 the Office was renamed Xyuanzhongyuan (Bureau of Buddhist Affairs).

It had been equalled to the highest authorities in the Empire: civil affairs, the army and the controlling power. Half of the commissioners of the Bureau were laymen, and the other half were monks.

The Bureau of Tibetan and Buddhist Affairs was created in 1329 as the result of a merger between two different bodies, Tibet (in the hands of Sakya) and the Buddhist Affairs Commission of Southern China.59

Work on the administrative division of the Yuan Empire was started when Kublai was still in power, but it was not completed until much later, in 1321.

According to the “New History of the Yuan” chronicle, the Empire was divided into twelve provinces.60 Apart from China and the Jin State, provinces included lands in

Mongolia (two provinces), the Tangut Empire, Amdo, part of Southern Siberia, as well as the whole of Korea.

Although Tibet was not included in them, it was previously divided into several “roads” (regions).

The head of Sakya had the supreme power over the area. He also employed an assistant clerk, the ponchen, who was in charge of civil and military affairs. This official was also under control of the Mongolian Bureau of Pacification.

According to Tibetan data, “he rules on the order of the Lama and the mandate of the Emperor.

He protects the two laws (religious and civil) and is responsible for peace (of the country) and prosperity (of religion)”.61

In 1264, Kham and Amdo (where the Mongol population was on the increase) were withdrawn from under the administration of Central Tibet.62 These lands were poorly controlled, and their unruly tribes often had to be “pacified”, which the Mongols did most effectively.

They sent troops there twenty-one times during the period from 1256 to 1355. Ü, Tsang and Ngari-Korsum were still directly subordinated to Phagpa Lama, but the Mongols formed administration agencies of lower rank there, with the task being not so much the administration, but rather supervision.63 The lands of Sakya were divided into thirteen districts which were mainly led by the monasteries.

Nevertheless, authority of the head of Sakya (in context of the framework of relations “priest – patron”) was recognized by all Tibetans.

The assumptions of some authors that Kublai Khan established his “sovereignty” or “central administration” in Tibet are unfounded. The control of the Mongols, which was implemented through the Bureau of Pacification, only represented help in maintaining peace in the country. Tibet was a country dependent on the Mongol Empire, but not of China.

The duties of the Mongol Emperor (the patron) to the Tibetan Lama (the priest) included protecting the territory, sending officials when their aid was necessary, the development of laws, post service, etc. Neither of these implied a Chinese rule.

In 1267, the Mongols had a census of the Tibetan population (during the Yuan there were another two censuses in 1287 and 1334). To do this, special emissaries were sent; these had a “mandate”, a golden paiza. The result was the division of all tax-paying people in lha-de (tributaries of the Tibetan Buddhist Church) and mide (the feudal lords).

Later, there was a trend of gradual increase in the number of lha-de at the expense of mi-de.

A system of taxation was established, as was military and administrative division by 10,000 and 1,000 households. As was the case in the Empire, a yam (postal station) system was established and stretched from the current province of Gansu to the region of Sakya.

For its time, this postal system was the most advanced in the world.

The messenger rode up to a postal station, changed to a fresh horse, galloped up to the next station, etc. Yams also provided horses for Tibetan and Mongolian officials.

When sending long-distance mail, the rider “passed the baton” to the next messenger after reaching the station.

This transport service (ula) continued to exist in Tibet until 1956.64 The fact that this service was weakly controlled by the Mongols was supported by findings about the unauthorized use of state-owned horses by monks.65 In 1311, the Empire had even issued a law that directly prohibited this.

At the beginning of the 14th century, imperial authorities often released prisoners to honour the holidays of Tibetan Buddhism, with this custom soon spreading to the Chinese New Year as well.

However, after some time the imperial authorities had to intervene again as amnesty had become too common.

There is evidence that the Tibetan Buddhist monks had advantages over Chinese Buddhist monks not only in Tibet, but also outside of its borders. On the other hand, Chinese Buddhism was supported as well.

For example, many places of worship, which were given to laymen or Taoists in the Chinese State of Song, were handed back after its fall, and some Taoists had been made Buddhist monks.

More and more Tibetan words came into the Mongolian language which made both nations closer.

The Mongols began to use Tibetan and even Indian first names (including religious ones) that were received from the Tibetan lamas who gave Buddhist initiations. Several of the great Mongol khans were named in such a manner as well:

Ayurbaribada, Suddhibala, Khosala, Rinchinbal, Ayushiridara.

Later, as the spread of Buddhism among the Mongolian people continued, this name borrowing became increasingly widespread. Now the Mongolian versions of the common Tibetan names are perhaps no less frequent than the actual Mongolian names.

Other words such as the names for the days of the week, some numbers, and the traditional calendar were also taken from the Tibetan language.

In turn, the Tibetan language itself also acquired a number of Mongolian words, mostly related to feudal titles and posts.

When Daknyi Sangpo Pel, the head of the Sakya, died in 1327, an internecine power struggle started amongst his sons, which he had from his seven wives.

Meanwhile conflicts in Khanbalyk occurred, and there the power changed hands eight times between the periods of ruling by Khaisan (1308) and Togon Temur (1333), with six khans changing between 1328 to 1333 alone.66

All these quick changes weakened the State of Yuan, and in the last few years of its existence the Great Khan was completely removed from ruling, with the throne being the object of a fierce struggle among dignitaries, feudals, and large numbers of the Khan’s relatives.

64 Shakabpa, 1988. 65 Franke, 1981. 66 Dalai, Ch., 1977, p.330–331.

was the head of the Karma Kagyu sect. Karmapa conducted the enthronement of Togon Temur, who became the last Yuan emperor that ruled in Beijing.

At that same time, Tibet was amidst a power struggle between the followers of Sakya and Kagyu. Jangchub Gyaltsen, a Kagyu follower, seized power in 1354, and the Yuan Emperor acknowledged his status in 1357.

Jangchub conducted redistribution of land between the landowners, introduced a single rate of land tax of 1/6 of the gathered crop, began to build roads and ferries, installed police and patrol services, and tightened the monastic discipline.

Meanwhile the Mongolian Dynasty was falling into decline and was no longer in a position to influence affairs in Tibet. In 1351, the Red Turban Rebellion started in China, a widespread revolt of peasants against the Mongol rule.

This movement expanded with leaders of various factions being often at odds with each other, while forging alliances with the Mongol commanders who were warring among themselves.

Zhu Yuanzhang, a Chinese monk, came out as the winner from that struggle, and Togon Temur fled from Beijing in 1368. Artistic arrangements of Tongon’s lamentations on this subject were preserved in chronicles:

“Oh, my Dadu, full of different kinds of jewellery! <...> Oh my Dadu, who supported all the Mongolian people!

My palace that was built by the Khutuktu, the cane palace, Kibung-Shandu, in which the Khubilgan Setsen Khan spent their summer — all seized by the Chinese! As for me, the Ukhagatu Khan, I have only my bad name left: coquetted with the Chinese…”, etc.67

It is stated in the “Ming Shi” chronicle that the first Ming Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang, being mindful of past raids into the state of Tan by the Tibetans, decided to send a message with the news of the power change in China.68 The governor of Shaanxi was sent to Tibet, so as those who worked in offices in the Yuan Empire, would come to the Chinese court for confirmation of their posts.

“Ming Shi” states that on 23rd August 1374, the official Wei Zhen was promoted from the post of commander of the Heychzhou Guard to the district military commissioner, becoming the highest official in the Heizhou and overseeing Heizhou, Do-Kham and Ü-Tsang, that is all of Tibet.69 However, this official is not mentioned in Tibetan historical literature,

as bureaus of management were not located in Tibet, but in the border areas near Heizhou and Xining. They did not represent a real political structure in Tibet, and Ming never had political power in Tibet, as there were no Chinese laws, taxes, etc. This indicates that Tibet was an independent state at that time.70