Difference between revisions of "Holy Wars in Buddhism and Islam"

(Created page with "<poem> Summary Often, when people think of the Muslim concept of jihad or holy war, they associate with it the negative connotation of a self-righteous campaign of vengeful de...") |

|||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{DisplayImages|255|89|457|1114|463|682|303|1006|382}} | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

Summary | Summary | ||

| − | Often, when people think of the Muslim concept of jihad or holy war, they associate with it the negative connotation of a self-righteous campaign of vengeful destruction in the name of God to convert others by force. They may acknowledge that Christianity had an equivalent with the Crusades, but do not usually view Buddhism as having anything similar. After all, they say, Buddhism is a religion of peace and does not have the technical term holy war. | + | Often, when [[people]] think of the [[Muslim]] {{Wiki|concept}} of jihad or {{Wiki|holy}} [[war]], they associate with it the negative connotation of a self-righteous campaign of vengeful destruction in the [[name]] of [[God]] to convert others by force. They may [[acknowledge]] that {{Wiki|Christianity}} had an {{Wiki|equivalent}} with the Crusades, but do not usually [[view]] [[Buddhism]] as having anything similar. After all, they say, [[Buddhism]] is a [[religion]] of [[peace]] and does not have the technical term {{Wiki|holy}} [[war]]. |

| − | A careful examination of the Buddhist texts, however, particularly The Kalachakra Tantra literature, reveals both external and internal levels of battle that could easily be called "holy wars." An unbiased study of Islam reveals the same. In both religions, leaders may exploit the external dimensions of holy war for political, economic, or personal gain, by using it to rouse their troops to battle | + | A careful examination of the [[Buddhist texts]], however, particularly The [[Kalachakra Tantra]] {{Wiki|literature}}, reveals both external and internal levels of battle that could easily be called "{{Wiki|holy}} wars." An unbiased study of {{Wiki|Islam}} reveals the same. In both [[religions]], leaders may exploit the external {{Wiki|dimensions}} of {{Wiki|holy}} [[war]] for {{Wiki|political}}, economic, or personal gain, by using it to rouse their troops to battle |

| − | Historical examples regarding Islam are well known; but one must not be rosy-eyed about Buddhism and think that it has been immune to this phenomenon. | + | Historical examples regarding {{Wiki|Islam}} are well known; but one must not be rosy-eyed about [[Buddhism]] and think that it has been immune to this [[phenomenon]]. |

| − | Nevertheless, in both religions, the main emphasis is on the internal spiritual battle against one’s own ignorance and destructive ways. | + | Nevertheless, in both [[religions]], the main emphasis is on the internal [[spiritual]] battle against one’s own [[ignorance]] and {{Wiki|destructive}} ways. |

Analysis | Analysis | ||

| − | Military Imagery in Buddhism | + | {{Wiki|Military}} [[Imagery]] in [[Buddhism]] |

| − | Shakyamuni Buddha was born into the Indian warrior caste and often used military imagery to describe the spiritual journey. He was the Triumphant One, who defeated the demonic forces (mara) of unawareness, distorted views, disturbing emotions, and impulsive karmic behavior. The eighth-century Indian Buddhist master Shantideva employs the metaphor of war repeatedly throughout Engaging in Bodhisattva Behavior: the real enemies to defeat are the disturbing emotions and attitudes that lie hidden in the mind. | + | [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] was born into the [[Indian]] [[warrior]] [[caste]] and often used {{Wiki|military}} [[imagery]] to describe the [[spiritual]] journey. He was the Triumphant One, who defeated the {{Wiki|demonic}} forces ([[mara]]) of unawareness, distorted [[views]], [[disturbing emotions]], and impulsive [[karmic]] {{Wiki|behavior}}. The eighth-century [[Indian]] [[Buddhist master]] [[Shantideva]] employs the {{Wiki|metaphor}} of [[war]] repeatedly throughout Engaging in [[Bodhisattva]] {{Wiki|Behavior}}: the {{Wiki|real}} enemies to defeat are the [[disturbing emotions]] and attitudes that lie hidden in the [[mind]]. |

| − | The Tibetans translate the Sanskrit term arhat, a liberated being, as foe-destroyer, someone who has destroyed the inner foes. From these examples, it would appear that in Buddhism, the call for a "holy war" is purely an internal spiritual matter. | + | The [[Tibetans]] translate the [[Sanskrit]] term [[arhat]], a {{Wiki|liberated}} being, as foe-destroyer, someone who has destroyed the inner foes. From these examples, it would appear that in [[Buddhism]], the call for a "{{Wiki|holy}} [[war]]" is purely an internal [[spiritual]] matter. |

| − | The Kalachakra Tantra, however, reveals an additional external dimension. | + | The [[Kalachakra Tantra]], however, reveals an additional external [[dimension]]. |

| − | The Legend of Shambhala | + | The [[Legend of Shambhala]] |

| − | According to tradition, Buddha taught The Kalachakra Tantra in Andhra, South India, in 880 BC, to the visiting King of Shambhala, Suchandra, and his entourage. King Suchandra brought the teachings back to his northern land, where they have flourished ever since. Shambhala is a human realm, not a Buddhist pure land, where all conditions are conducive for Kalachakra practice. Although an actual location on earth may represent it, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama explains that Shambhala exists purely as a spiritual realm. Despite the traditional literature describing the physical journey there, the only way to reach it is by intense Kalachakra meditation practice. | + | According to [[tradition]], [[Buddha]] taught The [[Kalachakra Tantra]] in Andhra, {{Wiki|South India}}, in 880 BC, to the visiting [[King of Shambhala]], [[Suchandra]], and his entourage. [[King Suchandra]] brought the teachings back to his northern land, where they have flourished ever since. [[Shambhala]] is a [[human realm]], not a [[Buddhist]] [[pure land]], where all [[conditions]] are conducive for [[Kalachakra]] practice. Although an actual location on [[earth]] may represent it, [[His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama]] explains that [[Shambhala]] [[exists]] purely as a [[spiritual realm]]. Despite the [[traditional]] {{Wiki|literature}} describing the [[physical]] journey there, the only way to reach it is by intense [[Kalachakra]] [[meditation]] practice. |

| − | Seven generations of kings after Suchandra, in 176 BC, King Manjushri Yashas gathered the religious leaders of Shambhala, specifically the brahman wise men, to give them predictions and a warning. Eight hundred years in the future, namely in 624 AD, a non-Indic religion will arise in Mecca. | + | Seven generations of [[kings]] after [[Suchandra]], in 176 BC, [[King]] [[Manjushri Yashas]] [[gathered]] the [[religious]] leaders of [[Shambhala]], specifically the [[brahman]] [[wise]] men, to give them predictions and a warning. Eight hundred years in the future, namely in 624 AD, a non-Indic [[religion]] will arise in {{Wiki|Mecca}}. |

| − | Because of a lack of unity among the | + | Because of a lack of unity among the [[brahmans]]’ [[people]] and laxity in following correctly the injunctions of their {{Wiki|Vedic}} [[scriptures]], many will accept this [[religion]] when its leaders threaten an invasion. To prevent this [[danger]], [[Manjushri Yashas]] united the [[people]] of [[Shambhala]] into a single "[[vajra-caste]]" by conferring upon them the [[Kalachakra]] [[empowerment]]. |

| − | By his act, the king became the First Kalki - the First Holder of the Caste. | + | By his act, the [[king]] became the [[First Kalki]] - the First Holder of the [[Caste]]. |

The Non-Indic Invaders | The Non-Indic Invaders | ||

| − | As the founding of Islam dates from in 622 AD, two years before Kalachakra’s predicted date, most scholars identify the non-Indic religion with that faith. Descriptions of the religion elsewhere in the Kalachakra texts as having the slaughter of cattle while reciting the name of its god, circumcision, veiled women, and prayer five times a day facing its holy land reinforce their conclusion. | + | As the founding of {{Wiki|Islam}} dates from in 622 AD, two years before [[Kalachakra’s]] predicted date, most [[scholars]] identify the non-Indic [[religion]] with that [[faith]]. Descriptions of the [[religion]] elsewhere in the [[Kalachakra]] texts as having the slaughter of cattle while reciting the [[name]] of its [[god]], circumcision, veiled women, and [[prayer]] five times a day facing its {{Wiki|holy}} land reinforce their conclusion. |

| − | The Sanskrit term for non-Indic here is mleccha (Tib. lalo), meaning someone who speaks incomprehensibly in a non-Sanskrit tongue. Hindus and Buddhists alike have applied it to all foreign invaders of North India, starting with the Macedonians and Greeks at the time of Alexander the Great. It carries the derogatory connotation of "barbarian" and indicates ethnocentric ignorance of any high culture the invading people might have. | + | The [[Sanskrit]] term for non-Indic here is [[mleccha]] (Tib. lalo), meaning someone who speaks incomprehensibly in a non-Sanskrit {{Wiki|tongue}}. [[Hindus]] and [[Buddhists]] alike have applied it to all foreign invaders of [[North]] [[India]], starting with the Macedonians and [[Greeks]] at the [[time]] of Alexander the Great. It carries the derogatory connotation of "{{Wiki|barbarian}}" and indicates ethnocentric [[ignorance]] of any high {{Wiki|culture}} the invading [[people]] might have. |

| − | The First Kalki further described the future non-Indic religion as having a line of eight great teachers: | + | The [[First Kalki]] further described the future non-Indic [[religion]] as having a line of eight great [[teachers]]: |

Adam | Adam | ||

| Line 34: | Line 35: | ||

Moses | Moses | ||

| − | Jesus | + | {{Wiki|Jesus}} |

Mani | Mani | ||

| Line 42: | Line 43: | ||

Mahdi | Mahdi | ||

| − | Muhammad will be born in Baghdad in the land of Mecca. Baghdad, however, was built only in 762 as the capital of the Arab Abbasad Caliphate (750 - 1258); Muhammad was born in 570 in Arabia. Mani was a third-century Persian who founded an eclectic religion, Manichaeism, which like the earlier Iranian religion Zoroastrianism, emphasized a struggle between the forces of good and evil. He was accepted as a prophet only by the heretical Manichaean Islamic sect found among some officials in the early Abbasad court in Baghdad. | + | Muhammad will be born in {{Wiki|Baghdad}} in the land of {{Wiki|Mecca}}. {{Wiki|Baghdad}}, however, was built only in 762 as the capital of the Arab Abbasad {{Wiki|Caliphate}} (750 - 1258); Muhammad was born in 570 in Arabia. Mani was a third-century {{Wiki|Persian}} who founded an eclectic [[religion]], {{Wiki|Manichaeism}}, which like the earlier {{Wiki|Iranian}} [[religion]] {{Wiki|Zoroastrianism}}, emphasized a struggle between the forces of [[good and evil]]. He was accepted as a prophet only by the {{Wiki|heretical}} {{Wiki|Manichaean}} {{Wiki|Islamic}} sect found among some officials in the early Abbasad court in {{Wiki|Baghdad}}. |

| − | The Abbasad caliphs severely persecuted its followers. Mahdi will be a future ruler (iman), descendent from Muhammad, who will lead the faithful to Jerusalem, restore Quranic law and order, and unite the followers of Islam in a single political state before the apocalypse that ends the world. He is the Islamic equivalent of a messiah. The concept of Mahdi became prominent only during the early Abbasad period, with three claimants to the title: a caliph, a rival in Mecca, and a martyr, in whose name an anti-Abbasad rebellion was led. The full concept of Mahdi as a messiah, however, did not appear until the end of the ninth century. | + | The Abbasad caliphs severely persecuted its followers. Mahdi will be a future [[ruler]] (iman), descendent from Muhammad, who will lead the faithful to Jerusalem, restore Quranic law and order, and unite the followers of {{Wiki|Islam}} in a single {{Wiki|political}} state before the apocalypse that ends the [[world]]. He is the {{Wiki|Islamic}} {{Wiki|equivalent}} of a messiah. The {{Wiki|concept}} of Mahdi became prominent only during the early Abbasad period, with three claimants to the title: a caliph, a rival in {{Wiki|Mecca}}, and a {{Wiki|martyr}}, in whose [[name]] an anti-Abbasad rebellion was led. The full {{Wiki|concept}} of Mahdi as a messiah, however, did not appear until the end of the ninth century. |

| − | From this evidence, we may conclude that Manjushri Yashas was predicting the rise of Manichaean Islam. Alternatively, we may conclude that the Kalachakra literature was written by Buddhist masters at a time when their information about Islam came from contact with the early Abbasids. Such masters would most likely have been from the great Buddhist monasteries in the Kabul region of Afghanistan. | + | From this {{Wiki|evidence}}, we may conclude that [[Manjushri Yashas]] was predicting the rise of {{Wiki|Manichaean}} {{Wiki|Islam}}. Alternatively, we may conclude that the [[Kalachakra]] {{Wiki|literature}} was written by [[Buddhist masters]] at a [[time]] when their [[information]] about {{Wiki|Islam}} came from [[contact]] with the early Abbasids. Such [[masters]] would most likely have been from the great [[Buddhist]] [[monasteries]] in the {{Wiki|Kabul}} region of {{Wiki|Afghanistan}}. |

| − | Many of these monasteries had architectural motifs similar to those in the Kalachakra mandala. They also had considerable contact with Tantric Buddhism in Kashmir, where it was often mixed with Hindu tantra. Moreover, Kabul as well had a sizable Hindu population at the time. | + | Many of these [[monasteries]] had architectural motifs similar to those in the [[Kalachakra mandala]]. They also had considerable [[contact]] with [[Tantric Buddhism]] in [[Kashmir]], where it was often mixed with [[Hindu]] [[tantra]]. Moreover, {{Wiki|Kabul}} as well had a sizable [[Hindu]] population at the [[time]]. |

| − | Regardless of which of the two theories we accept concerning the origin of The Kalachakra Tantra, we must surely look to Buddhist-Muslim relations in Afghanistan during the early Abbasad period to understand the context of its teachings on history and holy wars. | + | Regardless of which of the two theories we accept concerning the origin of The [[Kalachakra Tantra]], we must surely look to Buddhist-Muslim relations in {{Wiki|Afghanistan}} during the early Abbasad period to understand the context of its teachings on history and {{Wiki|holy}} wars. |

| − | The Prophesy of an Apocalyptic War | + | The [[Prophesy]] of an {{Wiki|Apocalyptic}} [[War]] |

| − | The First Kalki predicted that the followers of the non-Indic religion will some day rule India. From their capital in Delhi, their king Krinmati will attempt the conquest of Shambhala in 2424 AD. The commentaries suggest that Krinmati will be recognized as the messiah Mahdi. The Twenty-fifth Kalki, Raudrachakrin, will then invade India and defeat the non-Indics in a great war. His victory will mark the end of the kaliyuga - "the age of disputes," during which Dharma practice will degenerate. Afterwards, a new golden age will follow during which the teachings will flourish, especially those of Kalachakra. | + | The [[First Kalki]] predicted that the followers of the non-Indic [[religion]] will some day rule [[India]]. From their capital in {{Wiki|Delhi}}, their [[king]] Krinmati will attempt the conquest of [[Shambhala]] in 2424 AD. The commentaries suggest that Krinmati will be [[recognized]] as the messiah Mahdi. The Twenty-fifth [[Kalki]], [[Raudrachakrin]], will then invade [[India]] and defeat the non-Indics in a great [[war]]. His victory will mark the end of the [[kaliyuga]] - "the age of disputes," during which [[Dharma]] practice will degenerate. Afterwards, a new golden age will follow during which the teachings will flourish, especially those of [[Kalachakra]]. |

| − | The idea of a war between the forces of good and evil, ending with an apocalyptic battle led by a messiah, first appeared in Zoroastrianism, founded in the sixth century BC, several decades before Buddha was born. It entered Judaism some time between the second century BC and the second century AD. Subsequently, it made its way into early Christianity and Manichaeism, and later into Islam. | + | The [[idea]] of a [[war]] between the forces of [[good and evil]], ending with an {{Wiki|apocalyptic}} battle led by a messiah, first appeared in {{Wiki|Zoroastrianism}}, founded in the sixth century BC, several decades before [[Buddha]] was born. It entered {{Wiki|Judaism}} some [[time]] between the second century BC and the second century AD. Subsequently, it made its way into early {{Wiki|Christianity}} and {{Wiki|Manichaeism}}, and later into {{Wiki|Islam}}. |

| − | A variation of the apocalyptic theme also appeared in Hinduism, in The Vishnu Purana, dated approximately the fourth century AD. It relates that at the end of the kaliyuga, Vishnu will appear in his final incarnation as Kalki, taking birth in the village of Shambhala as the son of the brahman Vishnu Yashas. | + | A variation of the {{Wiki|apocalyptic}} theme also appeared in [[Hinduism]], in The {{Wiki|Vishnu Purana}}, dated approximately the fourth century AD. It relates that at the end of the [[kaliyuga]], [[Vishnu]] will appear in his final [[incarnation]] as [[Kalki]], taking [[birth]] in the village of [[Shambhala]] as the son of the [[brahman]] [[Vishnu]] [[Yashas]]. |

| − | He will defeat the non-Indics of the time who follow a path of destruction and will reawaken the minds of the people. Afterwards, in keeping with the Indian concept of cyclical time, a new golden age will follow, rather than a final judgment and the end of the world as in the non-Indic versions of the theme. It is difficult to establish whether The Vishnu Purana account derived from foreign influences and was adapted to the Indian mentality, or arose independently. | + | He will defeat the non-Indics of the [[time]] who follow a [[path]] of destruction and will reawaken the [[minds]] of the [[people]]. Afterwards, in keeping with the [[Indian]] {{Wiki|concept}} of cyclical [[time]], a new golden age will follow, rather than a final [[judgment]] and the end of the [[world]] as in the non-Indic versions of the theme. It is difficult to establish whether The {{Wiki|Vishnu Purana}} account derived from foreign [[influences]] and was adapted to the [[Indian]] [[mentality]], or arose independently. |

| − | In keeping with Buddha’s skillful means of teaching with terms and concepts familiar to his audience, The Kalachakra Tantra also uses the names and images from The Vishnu Purana. Its stated audience, after all, was primarily educated brahmans. The names not only include Shambhala, Kalki, the kaliyuga, and a variant of Vishnu Yashas, Manjushri Yashas, but also the same term mleccha for the non-Indics bent on destruction. | + | In keeping with [[Buddha’s]] [[skillful means]] of [[teaching]] with terms and [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] familiar to his audience, The [[Kalachakra Tantra]] also uses the names and images from The {{Wiki|Vishnu Purana}}. Its stated audience, after all, was primarily educated [[brahmans]]. The names not only include [[Shambhala]], [[Kalki]], the [[kaliyuga]], and a variant of [[Vishnu]] [[Yashas]], [[Manjushri Yashas]], but also the same term [[mleccha]] for the non-Indics bent on destruction. |

| − | In the Kalachakra version, however, the war has a symbolic meaning. | + | In the [[Kalachakra]] version, however, the [[war]] has a [[symbolic]] meaning. |

| − | The Symbolic Meaning of the War | + | The [[Symbolic]] Meaning of the [[War]] |

| − | In Stainless Light, the Second Kalki, Pundarika, explains that the fight with the non-Indic people of Mecca is not an actual war, since the real battle is within the body. The fifteenth-century Gelug commentator Kaydrubjey elaborates that Manjushri Yashas’s words do not suggest an actual campaign to kill the followers of the non-Indic religion. The First Kalki’s intention in describing the details of the war was to provide a metaphor for the inner battle of deep blissful awareness of voidness against unawareness and destructive behavior. | + | In [[Stainless Light]], the Second [[Kalki]], [[Pundarika]], explains that the fight with the non-Indic [[people]] of {{Wiki|Mecca}} is not an actual [[war]], since the {{Wiki|real}} battle is within the [[body]]. The fifteenth-century [[Gelug]] commentator [[Kaydrubjey]] elaborates that [[Manjushri]] Yashas’s words do not suggest an actual campaign to kill the followers of the non-Indic [[religion]]. The [[First Kalki’s]] [[intention]] in describing the details of the [[war]] was to provide a {{Wiki|metaphor}} for the inner battle of deep [[blissful awareness]] of [[voidness]] against unawareness and {{Wiki|destructive}} {{Wiki|behavior}}. |

| − | The Second Kalki clearly enumerates the hidden symbolism. Raudrachakrin represents the "mind-vajra," namely the clear light subtlest mind. Shambhala represents the state of great bliss in which the mind-vajra abides. Being a Kalki means that mind-vajra has the perfect level of deep awareness, namely simultaneously arising voidness and bliss. Raudrachakrin’s two generals, Rudra and Hanuman, stand for the two supporting kinds of deep awareness, that of the pratyekabuddhas and of the shravakas. | + | The Second [[Kalki]] clearly enumerates the hidden [[symbolism]]. [[Raudrachakrin]] represents the "mind-vajra," namely the [[clear light]] subtlest [[mind]]. [[Shambhala]] represents the state of great [[bliss]] in which the mind-vajra abides. Being a [[Kalki]] means that mind-vajra has the perfect [[level of deep awareness]], namely simultaneously [[arising]] [[voidness]] and [[bliss]]. Raudrachakrin’s two generals, [[Rudra]] and {{Wiki|Hanuman}}, stand for the two supporting kinds of deep [[awareness]], that of the [[pratyekabuddhas]] and of the [[shravakas]]. |

| − | The twelve Hindu gods who help win the war represent the cessation of the twelve links of dependent arising and of the twelve daily shifts of the karmic breaths. The links and the shifts both describe the mechanism perpetuating samsara. The four divisions of Raudrachakrin’s army represent the purest levels of the four immeasurable attitudes of love, compassion, joy, and equality. | + | The twelve [[Hindu]] [[gods]] who help win the [[war]] represent the [[cessation]] of the [[twelve links]] of [[dependent arising]] and of the twelve daily shifts of the [[karmic]] breaths. The links and the shifts both describe the {{Wiki|mechanism}} perpetuating [[samsara]]. The four divisions of Raudrachakrin’s {{Wiki|army}} represent the purest levels of the four [[immeasurable]] attitudes of [[love]], [[compassion]], [[joy]], and equality. |

| − | The non-Indic forces that Raudrachakrin and the divisions of his army defeat represent the minds of negative karmic forces. Muhammad represents the pathway of destructive behavior. The horse on which Mahdi rides symbolizes unawareness of behavioral cause and effect and of voidness. Mahdi’s four army divisions stand for hatred, malice, resentment, and prejudice, the exact opposites of the Shambhala armed forces. | + | The non-Indic forces that [[Raudrachakrin]] and the divisions of his {{Wiki|army}} defeat represent the [[minds]] of negative [[karmic]] forces. Muhammad represents the pathway of {{Wiki|destructive}} {{Wiki|behavior}}. The [[horse]] on which Mahdi rides [[symbolizes]] unawareness of {{Wiki|behavioral}} [[cause and effect]] and of [[voidness]]. Mahdi’s four {{Wiki|army}} divisions stand for [[hatred]], [[malice]], [[resentment]], and prejudice, the exact opposites of the [[Shambhala]] armed forces. |

| − | Raudrachakrin’s victory represents the attainment of the path to liberation and enlightenment. | + | Raudrachakrin’s victory represents the [[attainment]] of the [[path]] to [[liberation]] and [[enlightenment]]. |

| − | The Buddhist Didactic Method | + | The [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Didactic}} Method |

| − | Despite textual disclaimers of calling for an actual holy war, the implication here that Islam is a cruel religion, characterized by hatred, malice, and destructive behavior, can easily be used as evidence to support that Buddhism is anti-Muslim. Although some Buddhists of the past may in fact have had this bias and some Buddhists of today may likewise hold a sectarian view, one may also draw a different conclusion in light of one of the Mahayana Buddhist didactic methods. | + | Despite textual disclaimers of calling for an actual {{Wiki|holy}} [[war]], the implication here that {{Wiki|Islam}} is a {{Wiki|cruel}} [[religion]], characterized by [[hatred]], [[malice]], and {{Wiki|destructive}} {{Wiki|behavior}}, can easily be used as {{Wiki|evidence}} to support that [[Buddhism]] is anti-Muslim. Although some [[Buddhists]] of the past may in fact have had this bias and some [[Buddhists]] of today may likewise hold a {{Wiki|sectarian}} [[view]], one may also draw a different conclusion in [[light]] of one of the [[Mahayana]] [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|didactic}} methods. |

| − | For example, Mahayana texts present certain views as characterizing Hinayana Buddhism, such as selfishly working for one’s liberation alone, without regard for helping others. After all, the stated goal of Hinayana practitioners is self-liberation, not enlightenment for the sake of benefiting everyone. Although such description of Hinayana has led to prejudice, an educated objective study of Hinayana schools, such as Theravada, reveals a prominent role of meditation on love and compassion. | + | For example, [[Mahayana texts]] present certain [[views]] as characterizing [[Hinayana Buddhism]], such as selfishly working for one’s [[liberation]] alone, without regard for helping others. After all, the stated goal of [[Hinayana]] practitioners is [[self-liberation]], not [[enlightenment]] for the sake of benefiting everyone. Although such description of [[Hinayana]] has led to prejudice, an educated [[objective]] study of [[Hinayana schools]], such as [[Theravada]], reveals a prominent role of [[meditation]] on [[love]] and [[compassion]]. |

| − | One might conclude that Mahayana was simply ignorant of the actual Hinayana teachings. Alternatively, one might recognize that Mahayana is using here the method in Buddhist logic of taking positions to their absurd conclusions in order to help people avoid extremist views. The intention of this prasangika method is to caution practitioners to avoid the extreme of selfishness. | + | One might conclude that [[Mahayana]] was simply [[ignorant]] of the actual [[Hinayana]] teachings. Alternatively, one might [[recognize]] that [[Mahayana]] is using here the method in [[Buddhist logic]] of taking positions to their absurd conclusions in order to help [[people]] avoid extremist [[views]]. The [[intention]] of this [[prasangika]] method is to caution practitioners to avoid the extreme of [[selfishness]]. |

| − | The same analysis applies to the Mahayana presentations of the six schools of medieval Hindu and Jain philosophies. It also applies to each of the Tibetan Buddhist | + | The same analysis applies to the [[Mahayana]] presentations of the six schools of {{Wiki|medieval}} [[Hindu]] and [[Jain]] [[philosophies]]. It also applies to each of the [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[traditions]]’ presentations of the [[views]] of each other and the [[views]] of the native [[Tibetan]] [[Bon]] [[tradition]]. None of these presentations gives an accurate depiction. |

| − | Each exaggerates and distorts certain features of the others to illustrate various points. The same is true of the Kalachakra assertions about the cruelty of Islam and its potential threat. Although Buddhist teachers may claim that the prasangika method here of using Islam to illustrate spiritual danger is a skillful means, one might also argue that it is grossly lacking in diplomacy, especially in modern times. | + | Each exaggerates and distorts certain features of the others to illustrate various points. The same is true of the [[Kalachakra]] assertions about the [[cruelty]] of {{Wiki|Islam}} and its potential threat. Although [[Buddhist teachers]] may claim that the [[prasangika]] method here of using {{Wiki|Islam}} to illustrate [[spiritual]] [[danger]] is a [[skillful means]], one might also argue that it is grossly lacking in diplomacy, especially in {{Wiki|modern}} times. |

| − | The use of Islam to represent destructive threatening forces, however, is understandable when examined in the context of the early Abbasad period in the Kabul region of Afghanistan. | + | The use of {{Wiki|Islam}} to represent {{Wiki|destructive}} threatening forces, however, is understandable when examined in the context of the early Abbasad period in the {{Wiki|Kabul}} region of {{Wiki|Afghanistan}}. |

Buddhist-Islamic Relations during the Abbasid Period | Buddhist-Islamic Relations during the Abbasid Period | ||

| − | At the start of the period, the Abbasids ruled Bactria (northern Afghanistan), where they allowed the local Buddhists, Hindus, and Zoroastrians to keep their religions if they paid a poll tax. Many, however, voluntarily accepted Islam, especially among the landowners and the educated upper urban classes. Its high culture was more accessible than their own and they could avoid paying the heavy tax. | + | At the start of the period, the Abbasids ruled {{Wiki|Bactria}} (northern {{Wiki|Afghanistan}}), where they allowed the local [[Buddhists]], [[Hindus]], and Zoroastrians to keep their [[religions]] if they paid a poll tax. Many, however, voluntarily accepted {{Wiki|Islam}}, especially among the landowners and the educated upper urban classes. Its high {{Wiki|culture}} was more accessible than their own and they could avoid paying the heavy tax. |

| − | The Turki Shahis, allied with the Tibetans, ruled Kabul, where Buddhism and Hinduism were flourishing. The Buddhist rulers and spiritual leaders might easily have worried that a similar phenomenon, conversion out of convenience, would happen there. | + | The Turki Shahis, allied with the [[Tibetans]], ruled {{Wiki|Kabul}}, where [[Buddhism]] and [[Hinduism]] were flourishing. The [[Buddhist]] rulers and [[spiritual]] leaders might easily have worried that a similar [[phenomenon]], [[conversion]] out of convenience, would happen there. |

| − | The Turki Shahis ruled the region until 870, losing control of it only between 815 and 819. During those four years, the Abbasad Caliph al-Mamun invaded Kabul, forced the ruling shah to accept Islam, and sent a gold Buddha statue from Subahar Monastery there as booty to Mecca. In smashing the idols as the Prophet Muhammad had done, the caliph was demonstrating his authority to rule the entire Islamic world after vanquishing his brother in a civil war. He did not force all the Buddhists of Kabul to convert, however, nor did he destroy the monasteries. After the Abbasad army withdrew to fight against movements for autonomy in other parts of their empire, the Buddhist monasteries quickly recovered. | + | The Turki Shahis ruled the region until 870, losing control of it only between 815 and 819. During those four years, the Abbasad Caliph al-Mamun invaded {{Wiki|Kabul}}, forced the ruling shah to accept {{Wiki|Islam}}, and sent a {{Wiki|gold}} [[Buddha]] statue from Subahar [[Monastery]] there as booty to {{Wiki|Mecca}}. In smashing the idols as the {{Wiki|Prophet Muhammad}} had done, the caliph was demonstrating his authority to rule the entire {{Wiki|Islamic}} [[world]] after vanquishing his brother in a civil [[war]]. He did not force all the [[Buddhists]] of {{Wiki|Kabul}} to convert, however, nor did he destroy the [[monasteries]]. After the Abbasad {{Wiki|army}} withdrew to fight against movements for autonomy in other parts of their [[empire]], the [[Buddhist]] [[monasteries]] quickly recovered. |

| − | The next period in which the Kabul region came under Islamic rule was also short, between 870 and 879. It was conquered by the Saffarad rulers of an autonomous military state, remembered for its harshness and destruction of local cultures. The conquerors sent many Buddhist "idols" back as war trophies to the Abbasad caliph. When the successors to the Turki Shahis, the Hindu Shahis, retook the region, Buddhism and the monasteries once more recovered their previous splendor. | + | The next period in which the {{Wiki|Kabul}} region came under {{Wiki|Islamic}} rule was also short, between 870 and 879. It was conquered by the Saffarad rulers of an autonomous {{Wiki|military}} state, remembered for its harshness and destruction of local cultures. The conquerors sent many [[Buddhist]] "idols" back as [[war]] trophies to the Abbasad caliph. When the successors to the Turki Shahis, the [[Hindu]] Shahis, retook the region, [[Buddhism]] and the [[monasteries]] once more recovered their previous splendor. |

| − | The Turkic Ghaznavids conquered Kabul in the 980s. It was at about this time that the Kalachakra teachings openly appeared in India, transmitted in visions to two Indian masters attempting to reach Shambhala. Although the Muslim Ghaznavids tolerated Buddhism and Hinduism in Kabul, they smashed the Ismaili Islamic state of Multan in north central Pakistan in 1008. | + | The Turkic Ghaznavids conquered {{Wiki|Kabul}} in the 980s. It was at about this [[time]] that the [[Kalachakra]] teachings openly appeared in [[India]], transmitted in visions to two [[Indian]] [[masters]] attempting to reach [[Shambhala]]. Although the [[Muslim]] Ghaznavids tolerated [[Buddhism]] and [[Hinduism]] in {{Wiki|Kabul}}, they smashed the Ismaili {{Wiki|Islamic}} state of Multan in [[north]] central {{Wiki|Pakistan}} in 1008. |

| − | The Ismaili Fatimids in Egypt were the rivals of the Ghaznavids for supremacy over the entire Muslim world. After this victory, the Ghaznavad ruler Mahmud of Ghazni, driven undoubtedly by greed for more land and wealth, pressed his invasion further eastward as far as Madhura, south of Delhi. | + | The Ismaili Fatimids in {{Wiki|Egypt}} were the rivals of the Ghaznavids for supremacy over the entire [[Muslim]] [[world]]. After this victory, the Ghaznavad [[ruler]] Mahmud of Ghazni, driven undoubtedly by [[greed]] for more land and [[wealth]], pressed his invasion further eastward as far as [[Madhura]], [[south]] of {{Wiki|Delhi}}. |

| − | He looted and destroyed the wealthy Buddhist monasteries that lay in his path. When the Ghaznavad troops pushed northward from Delhi, however, and tried to invade Kashmir, the Kashmiri King Samgrama Raja, a supporter of both Buddhism and Hinduism, defeated them in 1021. This was the first attack on Kashmir by a Muslim army. | + | He looted and destroyed the wealthy [[Buddhist]] [[monasteries]] that lay in his [[path]]. When the Ghaznavad troops pushed northward from {{Wiki|Delhi}}, however, and tried to invade [[Kashmir]], the [[Kashmiri]] [[King]] Samgrama [[Raja]], a supporter of both [[Buddhism]] and [[Hinduism]], defeated them in 1021. This was the first attack on [[Kashmir]] by a [[Muslim]] {{Wiki|army}}. |

| − | The Kalachakra Tantra reached Tibet from Kashmir in 1027, the year predicted by the First Kalki. | + | The [[Kalachakra Tantra]] reached [[Tibet]] from [[Kashmir]] in 1027, the year predicted by the [[First Kalki]]. |

Correlation between the Predictions and History | Correlation between the Predictions and History | ||

| − | The First Kalki’s historical predictions, then, clearly fit the above times, but mold the events to illustrate lessons. The reference in the Kalachakra literature to the non-Indic invaders as Turushka, meaning Turkic people, undoubtedly refers to the Turkic Ghaznavids. However, the references to Turkic people are most likely later interpolations. The Ghaznavids were only the second Turkic people to adapt Islam, and this occurred in the late 970s. | + | The [[First Kalki’s]] historical predictions, then, clearly fit the above times, but mold the events to illustrate lessons. The reference in the [[Kalachakra]] {{Wiki|literature}} to the non-Indic invaders as Turushka, meaning Turkic [[people]], undoubtedly refers to the Turkic Ghaznavids. However, the references to Turkic [[people]] are most likely later interpolations. The Ghaznavids were only the second Turkic [[people]] to adapt {{Wiki|Islam}}, and this occurred in the late 970s. |

| − | The Western Qarakhanids of Kashgar were the first, in the 930s. On the other hand, the Turki Shahis, who ruled the Kabul region in the late eighth century - the most likely candidate period for the Kalachakra description of the non-Indic religion - were also Turkic people. Most of their rulers were Buddhist. | + | The {{Wiki|Western}} Qarakhanids of [[wikipedia:Kashgar|Kashgar]] were the first, in the 930s. On the other hand, the Turki Shahis, who ruled the {{Wiki|Kabul}} region in the late eighth century - the most likely candidate period for the [[Kalachakra]] description of the non-Indic [[religion]] - were also Turkic [[people]]. Most of their rulers were [[Buddhist]]. |

| − | As the thirteenth-century Sakya commentator Buton remarks about the Kalachakra presentation of history, "To scrutinize historical events of the past is meaningless." Nevertheless, Kaydrubjey explains that the predicted war between Shambhala and the non-Indic forces is not merely a metaphor without reference to a future historical reality. If that were so, then when The Kalachakra Tantra applies internal analogies for the planets and constellations, the absurd conclusion would follow that the heavenly bodies exist only as metaphors and have no external reference. | + | As the thirteenth-century [[Sakya]] commentator Buton remarks about the [[Kalachakra]] presentation of history, "To scrutinize historical events of the past is meaningless." Nevertheless, [[Kaydrubjey]] explains that the predicted [[war]] between [[Shambhala]] and the non-Indic forces is not merely a {{Wiki|metaphor}} without reference to a future historical [[reality]]. If that were so, then when The [[Kalachakra Tantra]] applies internal analogies for the {{Wiki|planets}} and [[constellations]], the absurd conclusion would follow that the [[heavenly]] [[bodies]] [[exist]] only as metaphors and have no external reference. |

| − | Kaydrubjey also cautions, however, against taking literally the additional Kalachakra prediction that the non-Indic religion will eventually spread to all twelve continents and Raudrachakrin’s teachings will overcome it there too. The prediction does not concern the specific non-Indic people described earlier, or their religious beliefs or practices. The name mleccha here merely refers to non-Dharmic forces and beliefs that contradict Buddha’s teachings. | + | [[Kaydrubjey]] also cautions, however, against taking literally the additional [[Kalachakra]] prediction that the non-Indic [[religion]] will eventually spread to all twelve continents and Raudrachakrin’s teachings will overcome it there too. The prediction does not [[concern]] the specific non-Indic [[people]] described earlier, or their [[religious]] [[beliefs]] or practices. The [[name]] [[mleccha]] here merely refers to non-Dharmic forces and [[beliefs]] that contradict [[Buddha’s teachings]]. |

| − | Thus, the prediction is that destructive forces inimical to spiritual practice - and not specifically a Muslim army - will attack in the future, and an external "holy war" against them will be necessary. The implicit message is that, if peaceful methods fail and one must fight a holy war, the struggle must always base itself on the Buddhist principles of compassion and deep awareness of reality. | + | Thus, the prediction is that {{Wiki|destructive}} forces inimical to [[spiritual]] practice - and not specifically a [[Muslim]] {{Wiki|army}} - will attack in the future, and an external "{{Wiki|holy}} [[war]]" against them will be necessary. The implicit message is that, if [[peaceful]] methods fail and one must fight a {{Wiki|holy}} [[war]], the struggle must always base itself on the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|principles}} of [[compassion]] and deep [[awareness]] of [[reality]]. |

| − | This is true despite the fact that in practice this guideline is extremely difficult to follow when training soldiers who are not bodhisattvas. Nevertheless, if the war is driven by the non-Indic principles of hatred, malice, resentment, and prejudice, future generations will see no difference between the ways of their ancestors and those of the non-Indic forces. Consequently, they will easily adopt the non-Indic ways. | + | This is true despite the fact that in practice this guideline is extremely difficult to follow when training soldiers who are not [[bodhisattvas]]. Nevertheless, if the [[war]] is driven by the non-Indic {{Wiki|principles}} of [[hatred]], [[malice]], [[resentment]], and prejudice, future generations will see no difference between the ways of their {{Wiki|ancestors}} and those of the non-Indic forces. Consequently, they will easily adopt the non-Indic ways. |

| − | The Islamic Concept of Jihad | + | The {{Wiki|Islamic}} {{Wiki|Concept}} of Jihad |

| − | Is one of the "barbarian" ways the Islamic concept of jihad? If so, is Kalachakra accurately describing jihad, or is it using the non-Indic invasion of Shambhala merely to represent an extreme to avoid? To avert interfaith misunderstanding, it is important to investigate these questions. | + | Is one of the "{{Wiki|barbarian}}" ways the {{Wiki|Islamic}} {{Wiki|concept}} of jihad? If so, is [[Kalachakra]] accurately describing jihad, or is it using the non-Indic invasion of [[Shambhala]] merely to represent an extreme to avoid? To avert interfaith misunderstanding, it is important to investigate these questions. |

| − | The Arabic word jihad means a struggle in which one needs to endure suffering and difficulties, such as hunger and thirst during Ramadan, the holy month of fasting. Those who engage in this struggle are mujahedin. One is reminded of the Buddhist teachings on patience for bodhisattvas to endure the difficulties of following the path to enlightenment. | + | The {{Wiki|Arabic}} [[word]] jihad means a struggle in which one needs to endure [[suffering]] and difficulties, such as hunger and [[thirst]] during Ramadan, the {{Wiki|holy}} month of [[fasting]]. Those who engage in this struggle are mujahedin. One is reminded of the [[Buddhist teachings]] on [[patience]] for [[bodhisattvas]] to endure the difficulties of following the [[path]] to [[enlightenment]]. |

| − | The Sunni division of Islam outlines five types of jihad. | + | The Sunni division of {{Wiki|Islam}} outlines five types of jihad. |

| − | (1) A military jihad is a defensive campaign against aggressors trying to harm Islam. It is not an offensive attack to convert others to Islam by force. | + | (1) A {{Wiki|military}} jihad is a defensive campaign against aggressors trying to harm {{Wiki|Islam}}. It is not an [[offensive]] attack to convert others to {{Wiki|Islam}} by force. |

(2) A jihad by resources entails giving financial and material support to the poor and needy. | (2) A jihad by resources entails giving financial and material support to the poor and needy. | ||

| Line 108: | Line 109: | ||

(3) A jihad by work is honestly supporting oneself and one’s family. | (3) A jihad by work is honestly supporting oneself and one’s family. | ||

| − | (4) A jihad by study is to acquire knowledge. | + | (4) A jihad by study is to acquire [[knowledge]]. |

| − | (5) A jihad against oneself is an internal struggle to overcome wishes and thoughts counter to the Muslim teachings. | + | (5) A jihad against oneself is an internal struggle to overcome wishes and [[thoughts]] counter to the [[Muslim]] teachings. |

| − | The Shiah divisions of Islam emphasize the first type of jihad, equating an attack on an Islamic state with an attack on the Islamic faith. Many Shiites also accept the fifth type, the internal spiritual jihad. | + | The Shiah divisions of {{Wiki|Islam}} emphasize the first type of jihad, equating an attack on an {{Wiki|Islamic}} state with an attack on the {{Wiki|Islamic}} [[faith]]. Many Shiites also accept the fifth type, the internal [[spiritual]] jihad. |

| − | Similarities between Buddhism and Islam | + | Similarities between [[Buddhism]] and {{Wiki|Islam}} |

| − | The Kalachakra presentation of the mythical Shambhala war and the Islamic discussion of jihad show remarkable similarities. Both Buddhist and Islamic holy wars are defensive tactics for stopping attacks by external hostile forces, and never offensive campaigns for winning converts. Both have internal spiritual levels of meaning, in which the battle is against negative thoughts and destructive emotions | + | The [[Kalachakra]] presentation of the [[mythical]] [[Shambhala]] [[war]] and the {{Wiki|Islamic}} [[discussion]] of jihad show remarkable similarities. Both [[Buddhist]] and {{Wiki|Islamic}} {{Wiki|holy}} wars are defensive tactics for stopping attacks by external {{Wiki|hostile}} forces, and never [[offensive]] campaigns for winning converts. Both have internal [[spiritual]] levels of meaning, in which the battle is against negative [[thoughts]] and [[destructive emotions]] |

| − | Both need to be waged based on ethical principles, not on the basis of prejudice and hatred. Thus, in presenting the non-Indic invasion of Shambhala as purely negative, the Kalachakra literature is in fact misrepresenting the concept of jihad in the prasangika manner of taking it to its logical extreme to illustrate a position to avoid. | + | Both need to be waged based on [[ethical]] {{Wiki|principles}}, not on the basis of prejudice and [[hatred]]. Thus, in presenting the non-Indic invasion of [[Shambhala]] as purely negative, the [[Kalachakra]] {{Wiki|literature}} is in fact misrepresenting the {{Wiki|concept}} of jihad in the [[prasangika]] [[manner]] of taking it to its [[logical]] extreme to illustrate a position to avoid. |

| − | Moreover, just as many leaders have distorted and exploited the concept of jihad for power and gain, the same has occurred with Shambhala and its discussion of war against destructive foreign forces. Agvan Dorjiev, the late nineteenth-century Russian Buryat Mongol assistant tutor of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, proclaimed that Russia was Shambhala and the Czar was a Kalki. In this way, he tried to convince the Thirteenth Dalai Lama to align with Russia against the "mleccha" British in the struggle for control of Central Asia. | + | Moreover, just as many leaders have distorted and exploited the {{Wiki|concept}} of jihad for power and gain, the same has occurred with [[Shambhala]] and its [[discussion]] of [[war]] against {{Wiki|destructive}} foreign forces. [[Agvan Dorjiev]], the late nineteenth-century {{Wiki|Russian}} [[Buryat]] Mongol assistant [[tutor]] of the [[Thirteenth Dalai Lama]], proclaimed that {{Wiki|Russia}} was [[Shambhala]] and the {{Wiki|Czar}} was a [[Kalki]]. In this way, he tried to convince the [[Thirteenth Dalai Lama]] to align with {{Wiki|Russia}} against the "[[mleccha]]" {{Wiki|British}} in the struggle for control of {{Wiki|Central Asia}}. |

| − | The Mongols have traditionally identified both King Suchandra of Shambhala and Chinggis Khan as incarnations of Vajrapani. Fighting for Shambhala, then, is fighting for the glory of Chinggis Khan and for Mongolia. Thus, Sukhe Batur - leader of the 1921 Mongolian Communist Revolution against the extremely harsh rule of the White Russian and Japanese-backed Baron von Ungern-Sternberg - inspired his troops with the Kalachakra account of the war to end the kaliyuga. | + | The {{Wiki|Mongols}} have [[traditionally]] identified both [[King Suchandra]] of [[Shambhala]] and {{Wiki|Chinggis Khan}} as [[incarnations]] of [[Vajrapani]]. Fighting for [[Shambhala]], then, is fighting for the glory of {{Wiki|Chinggis Khan}} and for [[Mongolia]]. Thus, Sukhe Batur - leader of the 1921 {{Wiki|Mongolian}} {{Wiki|Communist}} {{Wiki|Revolution}} against the extremely harsh rule of the {{Wiki|White Russian}} and Japanese-backed [[Baron von Ungern-Sternberg]] - inspired his troops with the [[Kalachakra]] account of the [[war]] to end the [[kaliyuga]]. |

| − | He promised them rebirth as warriors of the King of Shambhala, despite there being no textual foundation for his claim in the Kalachakra literature. During the Japanese occupation of Mongolia in the 1930s, the Japanese overlords, in turn, tried to gain Mongol allegiance and military support through a propaganda campaign that Japan was Shambhala. | + | He promised them [[rebirth]] as {{Wiki|warriors}} of the [[King of Shambhala]], despite there being no textual foundation for his claim in the [[Kalachakra]] {{Wiki|literature}}. During the [[Japanese]] {{Wiki|occupation}} of [[Mongolia]] in the 1930s, the [[Japanese]] overlords, in turn, tried to gain Mongol allegiance and {{Wiki|military}} support through a {{Wiki|propaganda}} campaign that [[Japan]] was [[Shambhala]]. |

Conclusion | Conclusion | ||

| − | Just as critics of Buddhism could focus on abuses of Kalachakra’s external level of spiritual battle and dismiss the internal level, and this would be unfair to Buddhism as a whole; the same is true regarding anti-Muslim critics of jihad. The advice in the Buddhist tantras regarding the spiritual teacher may be useful here. Almost every spiritual teacher has a mixture of good qualities and faults. Although a disciple must not deny the negative qualities of a teacher, to dwell on them will only cause anger and depression. If, instead, a disciple focuses on a teacher’s positive qualities, he or she will gain inspiration to follow the spiritual path. | + | Just as critics of [[Buddhism]] could focus on abuses of [[Kalachakra’s]] external level of [[spiritual]] battle and dismiss the internal level, and this would be unfair to [[Buddhism]] as a whole; the same is true regarding anti-Muslim critics of jihad. The advice in the [[Buddhist]] [[tantras]] regarding the [[spiritual teacher]] may be useful here. Almost every [[spiritual teacher]] has a mixture of good qualities and faults. Although a [[disciple]] must not deny the negative qualities of a [[teacher]], to dwell on them will only [[cause]] [[anger]] and {{Wiki|depression}}. If, instead, a [[disciple]] focuses on a teacher’s positive qualities, he or she will gain inspiration to follow the [[spiritual]] [[path]]. |

| − | The same can be said about the Buddhist and Islamic teachings regarding holy wars. Both religions have seen abuses of its calls for an external battle when destructive forces threaten religious practice. Without denying or dwelling on these abuses, one can gain inspiration by focusing on the benefits of waging an inner holy war in either creed. | + | The same can be said about the [[Buddhist]] and {{Wiki|Islamic}} teachings regarding {{Wiki|holy}} wars. Both [[religions]] have seen abuses of its calls for an external battle when {{Wiki|destructive}} forces threaten [[religious]] practice. Without denying or dwelling on these abuses, one can gain inspiration by focusing on the benefits of waging an inner {{Wiki|holy}} [[war]] in either [[creed]]. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

[[Category:Shambhala]] | [[Category:Shambhala]] | ||

Latest revision as of 08:56, 30 December 2013

Summary

Often, when people think of the Muslim concept of jihad or holy war, they associate with it the negative connotation of a self-righteous campaign of vengeful destruction in the name of God to convert others by force. They may acknowledge that Christianity had an equivalent with the Crusades, but do not usually view Buddhism as having anything similar. After all, they say, Buddhism is a religion of peace and does not have the technical term holy war.

A careful examination of the Buddhist texts, however, particularly The Kalachakra Tantra literature, reveals both external and internal levels of battle that could easily be called "holy wars." An unbiased study of Islam reveals the same. In both religions, leaders may exploit the external dimensions of holy war for political, economic, or personal gain, by using it to rouse their troops to battle

Historical examples regarding Islam are well known; but one must not be rosy-eyed about Buddhism and think that it has been immune to this phenomenon.

Nevertheless, in both religions, the main emphasis is on the internal spiritual battle against one’s own ignorance and destructive ways.

Analysis

Military Imagery in Buddhism

Shakyamuni Buddha was born into the Indian warrior caste and often used military imagery to describe the spiritual journey. He was the Triumphant One, who defeated the demonic forces (mara) of unawareness, distorted views, disturbing emotions, and impulsive karmic behavior. The eighth-century Indian Buddhist master Shantideva employs the metaphor of war repeatedly throughout Engaging in Bodhisattva Behavior: the real enemies to defeat are the disturbing emotions and attitudes that lie hidden in the mind.

The Tibetans translate the Sanskrit term arhat, a liberated being, as foe-destroyer, someone who has destroyed the inner foes. From these examples, it would appear that in Buddhism, the call for a "holy war" is purely an internal spiritual matter.

The Kalachakra Tantra, however, reveals an additional external dimension.

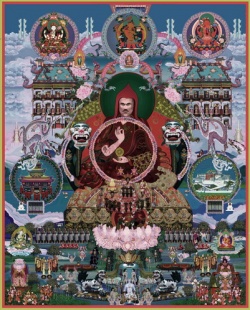

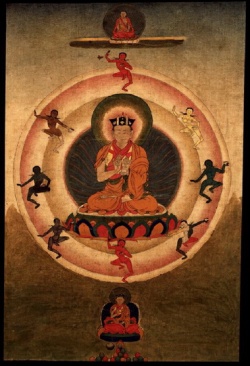

The Legend of Shambhala

According to tradition, Buddha taught The Kalachakra Tantra in Andhra, South India, in 880 BC, to the visiting King of Shambhala, Suchandra, and his entourage. King Suchandra brought the teachings back to his northern land, where they have flourished ever since. Shambhala is a human realm, not a Buddhist pure land, where all conditions are conducive for Kalachakra practice. Although an actual location on earth may represent it, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama explains that Shambhala exists purely as a spiritual realm. Despite the traditional literature describing the physical journey there, the only way to reach it is by intense Kalachakra meditation practice.

Seven generations of kings after Suchandra, in 176 BC, King Manjushri Yashas gathered the religious leaders of Shambhala, specifically the brahman wise men, to give them predictions and a warning. Eight hundred years in the future, namely in 624 AD, a non-Indic religion will arise in Mecca.

Because of a lack of unity among the brahmans’ people and laxity in following correctly the injunctions of their Vedic scriptures, many will accept this religion when its leaders threaten an invasion. To prevent this danger, Manjushri Yashas united the people of Shambhala into a single "vajra-caste" by conferring upon them the Kalachakra empowerment.

By his act, the king became the First Kalki - the First Holder of the Caste.

The Non-Indic Invaders

As the founding of Islam dates from in 622 AD, two years before Kalachakra’s predicted date, most scholars identify the non-Indic religion with that faith. Descriptions of the religion elsewhere in the Kalachakra texts as having the slaughter of cattle while reciting the name of its god, circumcision, veiled women, and prayer five times a day facing its holy land reinforce their conclusion.

The Sanskrit term for non-Indic here is mleccha (Tib. lalo), meaning someone who speaks incomprehensibly in a non-Sanskrit tongue. Hindus and Buddhists alike have applied it to all foreign invaders of North India, starting with the Macedonians and Greeks at the time of Alexander the Great. It carries the derogatory connotation of "barbarian" and indicates ethnocentric ignorance of any high culture the invading people might have.

The First Kalki further described the future non-Indic religion as having a line of eight great teachers:

Adam

Noah

Abraham

Moses

Jesus

Mani

Muhammad

Mahdi

Muhammad will be born in Baghdad in the land of Mecca. Baghdad, however, was built only in 762 as the capital of the Arab Abbasad Caliphate (750 - 1258); Muhammad was born in 570 in Arabia. Mani was a third-century Persian who founded an eclectic religion, Manichaeism, which like the earlier Iranian religion Zoroastrianism, emphasized a struggle between the forces of good and evil. He was accepted as a prophet only by the heretical Manichaean Islamic sect found among some officials in the early Abbasad court in Baghdad.

The Abbasad caliphs severely persecuted its followers. Mahdi will be a future ruler (iman), descendent from Muhammad, who will lead the faithful to Jerusalem, restore Quranic law and order, and unite the followers of Islam in a single political state before the apocalypse that ends the world. He is the Islamic equivalent of a messiah. The concept of Mahdi became prominent only during the early Abbasad period, with three claimants to the title: a caliph, a rival in Mecca, and a martyr, in whose name an anti-Abbasad rebellion was led. The full concept of Mahdi as a messiah, however, did not appear until the end of the ninth century.

From this evidence, we may conclude that Manjushri Yashas was predicting the rise of Manichaean Islam. Alternatively, we may conclude that the Kalachakra literature was written by Buddhist masters at a time when their information about Islam came from contact with the early Abbasids. Such masters would most likely have been from the great Buddhist monasteries in the Kabul region of Afghanistan.

Many of these monasteries had architectural motifs similar to those in the Kalachakra mandala. They also had considerable contact with Tantric Buddhism in Kashmir, where it was often mixed with Hindu tantra. Moreover, Kabul as well had a sizable Hindu population at the time.

Regardless of which of the two theories we accept concerning the origin of The Kalachakra Tantra, we must surely look to Buddhist-Muslim relations in Afghanistan during the early Abbasad period to understand the context of its teachings on history and holy wars.

The Prophesy of an Apocalyptic War

The First Kalki predicted that the followers of the non-Indic religion will some day rule India. From their capital in Delhi, their king Krinmati will attempt the conquest of Shambhala in 2424 AD. The commentaries suggest that Krinmati will be recognized as the messiah Mahdi. The Twenty-fifth Kalki, Raudrachakrin, will then invade India and defeat the non-Indics in a great war. His victory will mark the end of the kaliyuga - "the age of disputes," during which Dharma practice will degenerate. Afterwards, a new golden age will follow during which the teachings will flourish, especially those of Kalachakra.

The idea of a war between the forces of good and evil, ending with an apocalyptic battle led by a messiah, first appeared in Zoroastrianism, founded in the sixth century BC, several decades before Buddha was born. It entered Judaism some time between the second century BC and the second century AD. Subsequently, it made its way into early Christianity and Manichaeism, and later into Islam.

A variation of the apocalyptic theme also appeared in Hinduism, in The Vishnu Purana, dated approximately the fourth century AD. It relates that at the end of the kaliyuga, Vishnu will appear in his final incarnation as Kalki, taking birth in the village of Shambhala as the son of the brahman Vishnu Yashas.

He will defeat the non-Indics of the time who follow a path of destruction and will reawaken the minds of the people. Afterwards, in keeping with the Indian concept of cyclical time, a new golden age will follow, rather than a final judgment and the end of the world as in the non-Indic versions of the theme. It is difficult to establish whether The Vishnu Purana account derived from foreign influences and was adapted to the Indian mentality, or arose independently.

In keeping with Buddha’s skillful means of teaching with terms and concepts familiar to his audience, The Kalachakra Tantra also uses the names and images from The Vishnu Purana. Its stated audience, after all, was primarily educated brahmans. The names not only include Shambhala, Kalki, the kaliyuga, and a variant of Vishnu Yashas, Manjushri Yashas, but also the same term mleccha for the non-Indics bent on destruction.

In the Kalachakra version, however, the war has a symbolic meaning.

The Symbolic Meaning of the War

In Stainless Light, the Second Kalki, Pundarika, explains that the fight with the non-Indic people of Mecca is not an actual war, since the real battle is within the body. The fifteenth-century Gelug commentator Kaydrubjey elaborates that Manjushri Yashas’s words do not suggest an actual campaign to kill the followers of the non-Indic religion. The First Kalki’s intention in describing the details of the war was to provide a metaphor for the inner battle of deep blissful awareness of voidness against unawareness and destructive behavior.

The Second Kalki clearly enumerates the hidden symbolism. Raudrachakrin represents the "mind-vajra," namely the clear light subtlest mind. Shambhala represents the state of great bliss in which the mind-vajra abides. Being a Kalki means that mind-vajra has the perfect level of deep awareness, namely simultaneously arising voidness and bliss. Raudrachakrin’s two generals, Rudra and Hanuman, stand for the two supporting kinds of deep awareness, that of the pratyekabuddhas and of the shravakas.

The twelve Hindu gods who help win the war represent the cessation of the twelve links of dependent arising and of the twelve daily shifts of the karmic breaths. The links and the shifts both describe the mechanism perpetuating samsara. The four divisions of Raudrachakrin’s army represent the purest levels of the four immeasurable attitudes of love, compassion, joy, and equality.

The non-Indic forces that Raudrachakrin and the divisions of his army defeat represent the minds of negative karmic forces. Muhammad represents the pathway of destructive behavior. The horse on which Mahdi rides symbolizes unawareness of behavioral cause and effect and of voidness. Mahdi’s four army divisions stand for hatred, malice, resentment, and prejudice, the exact opposites of the Shambhala armed forces.

Raudrachakrin’s victory represents the attainment of the path to liberation and enlightenment.

The Buddhist Didactic Method

Despite textual disclaimers of calling for an actual holy war, the implication here that Islam is a cruel religion, characterized by hatred, malice, and destructive behavior, can easily be used as evidence to support that Buddhism is anti-Muslim. Although some Buddhists of the past may in fact have had this bias and some Buddhists of today may likewise hold a sectarian view, one may also draw a different conclusion in light of one of the Mahayana Buddhist didactic methods.

For example, Mahayana texts present certain views as characterizing Hinayana Buddhism, such as selfishly working for one’s liberation alone, without regard for helping others. After all, the stated goal of Hinayana practitioners is self-liberation, not enlightenment for the sake of benefiting everyone. Although such description of Hinayana has led to prejudice, an educated objective study of Hinayana schools, such as Theravada, reveals a prominent role of meditation on love and compassion.

One might conclude that Mahayana was simply ignorant of the actual Hinayana teachings. Alternatively, one might recognize that Mahayana is using here the method in Buddhist logic of taking positions to their absurd conclusions in order to help people avoid extremist views. The intention of this prasangika method is to caution practitioners to avoid the extreme of selfishness.

The same analysis applies to the Mahayana presentations of the six schools of medieval Hindu and Jain philosophies. It also applies to each of the Tibetan Buddhist traditions’ presentations of the views of each other and the views of the native Tibetan Bon tradition. None of these presentations gives an accurate depiction.

Each exaggerates and distorts certain features of the others to illustrate various points. The same is true of the Kalachakra assertions about the cruelty of Islam and its potential threat. Although Buddhist teachers may claim that the prasangika method here of using Islam to illustrate spiritual danger is a skillful means, one might also argue that it is grossly lacking in diplomacy, especially in modern times.

The use of Islam to represent destructive threatening forces, however, is understandable when examined in the context of the early Abbasad period in the Kabul region of Afghanistan.

Buddhist-Islamic Relations during the Abbasid Period

At the start of the period, the Abbasids ruled Bactria (northern Afghanistan), where they allowed the local Buddhists, Hindus, and Zoroastrians to keep their religions if they paid a poll tax. Many, however, voluntarily accepted Islam, especially among the landowners and the educated upper urban classes. Its high culture was more accessible than their own and they could avoid paying the heavy tax.

The Turki Shahis, allied with the Tibetans, ruled Kabul, where Buddhism and Hinduism were flourishing. The Buddhist rulers and spiritual leaders might easily have worried that a similar phenomenon, conversion out of convenience, would happen there.

The Turki Shahis ruled the region until 870, losing control of it only between 815 and 819. During those four years, the Abbasad Caliph al-Mamun invaded Kabul, forced the ruling shah to accept Islam, and sent a gold Buddha statue from Subahar Monastery there as booty to Mecca. In smashing the idols as the Prophet Muhammad had done, the caliph was demonstrating his authority to rule the entire Islamic world after vanquishing his brother in a civil war. He did not force all the Buddhists of Kabul to convert, however, nor did he destroy the monasteries. After the Abbasad army withdrew to fight against movements for autonomy in other parts of their empire, the Buddhist monasteries quickly recovered.

The next period in which the Kabul region came under Islamic rule was also short, between 870 and 879. It was conquered by the Saffarad rulers of an autonomous military state, remembered for its harshness and destruction of local cultures. The conquerors sent many Buddhist "idols" back as war trophies to the Abbasad caliph. When the successors to the Turki Shahis, the Hindu Shahis, retook the region, Buddhism and the monasteries once more recovered their previous splendor.

The Turkic Ghaznavids conquered Kabul in the 980s. It was at about this time that the Kalachakra teachings openly appeared in India, transmitted in visions to two Indian masters attempting to reach Shambhala. Although the Muslim Ghaznavids tolerated Buddhism and Hinduism in Kabul, they smashed the Ismaili Islamic state of Multan in north central Pakistan in 1008.

The Ismaili Fatimids in Egypt were the rivals of the Ghaznavids for supremacy over the entire Muslim world. After this victory, the Ghaznavad ruler Mahmud of Ghazni, driven undoubtedly by greed for more land and wealth, pressed his invasion further eastward as far as Madhura, south of Delhi.

He looted and destroyed the wealthy Buddhist monasteries that lay in his path. When the Ghaznavad troops pushed northward from Delhi, however, and tried to invade Kashmir, the Kashmiri King Samgrama Raja, a supporter of both Buddhism and Hinduism, defeated them in 1021. This was the first attack on Kashmir by a Muslim army.

The Kalachakra Tantra reached Tibet from Kashmir in 1027, the year predicted by the First Kalki.

Correlation between the Predictions and History

The First Kalki’s historical predictions, then, clearly fit the above times, but mold the events to illustrate lessons. The reference in the Kalachakra literature to the non-Indic invaders as Turushka, meaning Turkic people, undoubtedly refers to the Turkic Ghaznavids. However, the references to Turkic people are most likely later interpolations. The Ghaznavids were only the second Turkic people to adapt Islam, and this occurred in the late 970s.

The Western Qarakhanids of Kashgar were the first, in the 930s. On the other hand, the Turki Shahis, who ruled the Kabul region in the late eighth century - the most likely candidate period for the Kalachakra description of the non-Indic religion - were also Turkic people. Most of their rulers were Buddhist.

As the thirteenth-century Sakya commentator Buton remarks about the Kalachakra presentation of history, "To scrutinize historical events of the past is meaningless." Nevertheless, Kaydrubjey explains that the predicted war between Shambhala and the non-Indic forces is not merely a metaphor without reference to a future historical reality. If that were so, then when The Kalachakra Tantra applies internal analogies for the planets and constellations, the absurd conclusion would follow that the heavenly bodies exist only as metaphors and have no external reference.

Kaydrubjey also cautions, however, against taking literally the additional Kalachakra prediction that the non-Indic religion will eventually spread to all twelve continents and Raudrachakrin’s teachings will overcome it there too. The prediction does not concern the specific non-Indic people described earlier, or their religious beliefs or practices. The name mleccha here merely refers to non-Dharmic forces and beliefs that contradict Buddha’s teachings.

Thus, the prediction is that destructive forces inimical to spiritual practice - and not specifically a Muslim army - will attack in the future, and an external "holy war" against them will be necessary. The implicit message is that, if peaceful methods fail and one must fight a holy war, the struggle must always base itself on the Buddhist principles of compassion and deep awareness of reality.

This is true despite the fact that in practice this guideline is extremely difficult to follow when training soldiers who are not bodhisattvas. Nevertheless, if the war is driven by the non-Indic principles of hatred, malice, resentment, and prejudice, future generations will see no difference between the ways of their ancestors and those of the non-Indic forces. Consequently, they will easily adopt the non-Indic ways.

The Islamic Concept of Jihad

Is one of the "barbarian" ways the Islamic concept of jihad? If so, is Kalachakra accurately describing jihad, or is it using the non-Indic invasion of Shambhala merely to represent an extreme to avoid? To avert interfaith misunderstanding, it is important to investigate these questions.

The Arabic word jihad means a struggle in which one needs to endure suffering and difficulties, such as hunger and thirst during Ramadan, the holy month of fasting. Those who engage in this struggle are mujahedin. One is reminded of the Buddhist teachings on patience for bodhisattvas to endure the difficulties of following the path to enlightenment.

The Sunni division of Islam outlines five types of jihad.

(1) A military jihad is a defensive campaign against aggressors trying to harm Islam. It is not an offensive attack to convert others to Islam by force.

(2) A jihad by resources entails giving financial and material support to the poor and needy.

(3) A jihad by work is honestly supporting oneself and one’s family.

(4) A jihad by study is to acquire knowledge.

(5) A jihad against oneself is an internal struggle to overcome wishes and thoughts counter to the Muslim teachings.

The Shiah divisions of Islam emphasize the first type of jihad, equating an attack on an Islamic state with an attack on the Islamic faith. Many Shiites also accept the fifth type, the internal spiritual jihad.

Similarities between Buddhism and Islam

The Kalachakra presentation of the mythical Shambhala war and the Islamic discussion of jihad show remarkable similarities. Both Buddhist and Islamic holy wars are defensive tactics for stopping attacks by external hostile forces, and never offensive campaigns for winning converts. Both have internal spiritual levels of meaning, in which the battle is against negative thoughts and destructive emotions

Both need to be waged based on ethical principles, not on the basis of prejudice and hatred. Thus, in presenting the non-Indic invasion of Shambhala as purely negative, the Kalachakra literature is in fact misrepresenting the concept of jihad in the prasangika manner of taking it to its logical extreme to illustrate a position to avoid.

Moreover, just as many leaders have distorted and exploited the concept of jihad for power and gain, the same has occurred with Shambhala and its discussion of war against destructive foreign forces. Agvan Dorjiev, the late nineteenth-century Russian Buryat Mongol assistant tutor of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, proclaimed that Russia was Shambhala and the Czar was a Kalki. In this way, he tried to convince the Thirteenth Dalai Lama to align with Russia against the "mleccha" British in the struggle for control of Central Asia.

The Mongols have traditionally identified both King Suchandra of Shambhala and Chinggis Khan as incarnations of Vajrapani. Fighting for Shambhala, then, is fighting for the glory of Chinggis Khan and for Mongolia. Thus, Sukhe Batur - leader of the 1921 Mongolian Communist Revolution against the extremely harsh rule of the White Russian and Japanese-backed Baron von Ungern-Sternberg - inspired his troops with the Kalachakra account of the war to end the kaliyuga.

He promised them rebirth as warriors of the King of Shambhala, despite there being no textual foundation for his claim in the Kalachakra literature. During the Japanese occupation of Mongolia in the 1930s, the Japanese overlords, in turn, tried to gain Mongol allegiance and military support through a propaganda campaign that Japan was Shambhala.

Conclusion

Just as critics of Buddhism could focus on abuses of Kalachakra’s external level of spiritual battle and dismiss the internal level, and this would be unfair to Buddhism as a whole; the same is true regarding anti-Muslim critics of jihad. The advice in the Buddhist tantras regarding the spiritual teacher may be useful here. Almost every spiritual teacher has a mixture of good qualities and faults. Although a disciple must not deny the negative qualities of a teacher, to dwell on them will only cause anger and depression. If, instead, a disciple focuses on a teacher’s positive qualities, he or she will gain inspiration to follow the spiritual path.

The same can be said about the Buddhist and Islamic teachings regarding holy wars. Both religions have seen abuses of its calls for an external battle when destructive forces threaten religious practice. Without denying or dwelling on these abuses, one can gain inspiration by focusing on the benefits of waging an inner holy war in either creed.