In the Year of the Ox, understanding what makes the Chinese world view so exceptional may be crucial

- The Chinese world view is organic, systemic and indeterminate, recognising chance, contradictions and paradoxes, and different time cycles

- Within the next few decades, the Chinese, Indian and Islamic world view will all inevitably challenge US exceptionalism

The Lunar New Year is time for family and reflection, when Chinese families look back at the year gone by and speculate on the next cycle. The Gengzi Year of the Rat, historically associated with disaster – the Opium War (1840), Boxer Rebellion (1900), and famine (1960) – brought a calamitous pandemic and global recession.

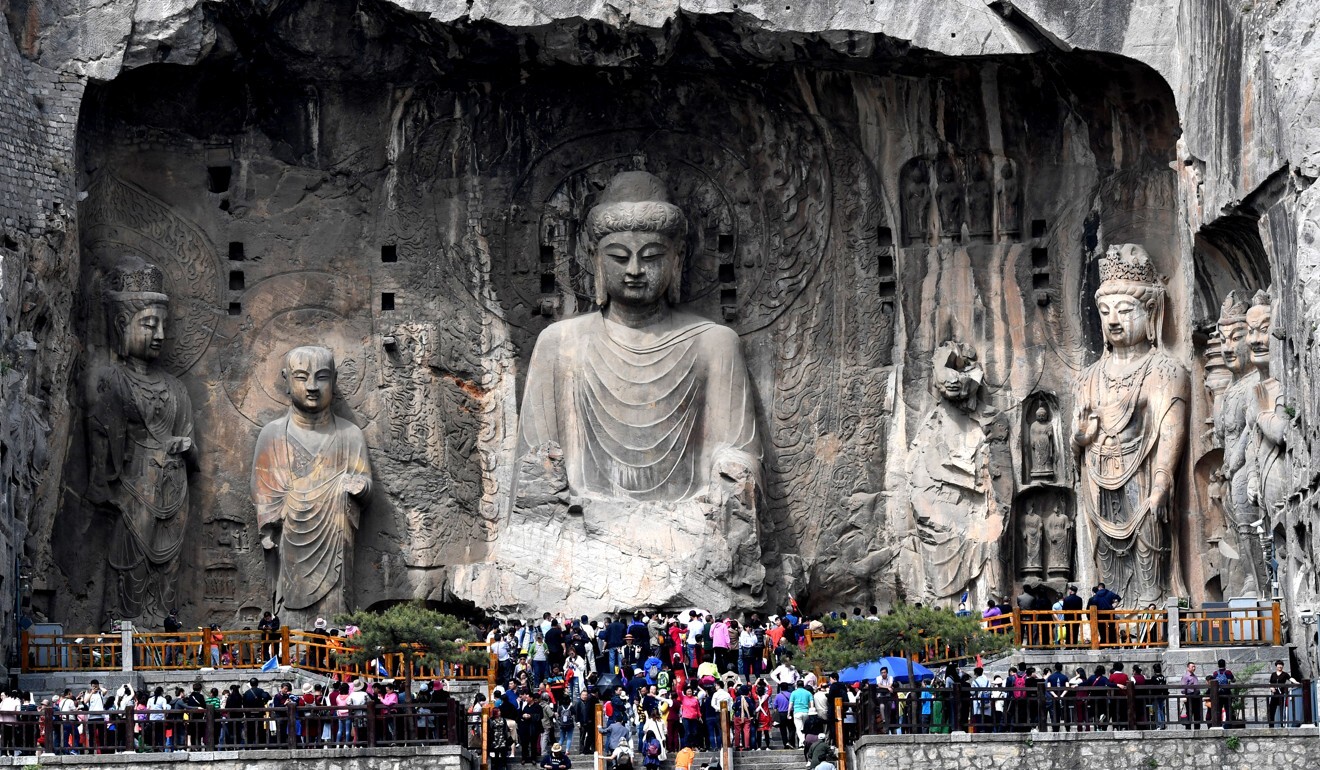

Cultural generalisations tread on dangerous ground, because modern China has been shaped by its tumultuous engagement with the rising West since the 17th century. In the first millennium, Buddhism came from India. In the last 300 years, China absorbed communism and science and technology from the West. Both Buddhism and communism no longer prevail in their countries of origin.

Nevertheless, the earliest Western sinologists noted how China was different. French historian Jacques Gernet’s A History of Chinese Civilisation observed how “its fundamental traditions – political religious, aesthetic, juridical – are different from those of the Indian world, of Islam, of the Christian world of the West”.

Harvard professor Benjamin Schwartz highlighted “correlative cosmology” (yin-yang) as a mode of thinking that runs quite distinct from Western philosophy. This “organic humanism”, in which the Chinese regarded man and nature as one under heaven, was one reason Cambridge sinologist Joseph Needham thought China did not develop modern science.

There is little dispute that modern science is a Western invention. Before the Renaissance, European thinkers drew eclectically from Greek, Arab and Indian mathematics, philosophy and arts. One of the founders of the Scientific Revolution, Francis Bacon, attributed power to the use of gunpowder, the compass and printing. All three were Chinese inventions.

The West developed science in the 17th century from its logical or reductionist search for cause and effect in nature. Man and nature were separated, just as mind and body were treated as distinct entities.

As Future Shock author Alvin Toffler said: “One of the most highly developed skills in contemporary Western civilisation is dissection: the split-up of problems into their smallest possible components. We are good at it. So good, we often forget to put the pieces back together again.”

Chinese thinking rarely went down this reductionist route, because it instinctively saw the whole as more than the sum of its parts.

01:14

Archaeologists in China say they’ve found the earliest example of herbal medicine in imperial tomb

What is so special about Chinese correlative thinking? It is organic, systemic and indeterminate, recognising chance, contradictions and paradoxes, different time cycles and the inseparability of observer and observed. Contrast this with the standard economic analysis that is partial and context-free and, other things being equal, timeless, random yet predictable, depending on rational man as the agent in a free market.

As philosopher Stephen Toulmin argued about scientific modernity, the West took off in the 17th century towards theory-based methodology that sought universal, timeless and context-free principles about nature, and by extension, also about social science. Science could explain, predict and manage nature. Humanity was split from science into the arts.

Determinism required clear concepts that were absolute and objective. Economics copied classical physics in trying to explain the world scientifically in mathematical models that we know today are flawed because they ignored the irrationality of man and markets.

As French sinologist and linguist Marcel Garnet explained: “The Chinese are either superstitious or practical, or rather they are both at once. It is this ‘both at once’ that a Westerner often finds hard to grasp.”

The Chinese Taoist “correlative cosmology” saw life as systems of interacting opposites – male and female, cold and hot, engaging with each other in constant change and evolution. Life therefore is seen in cycles or feedback loops that are mathematically difficult to predict with exactitude.

In short, ancient Chinese thinking was dialectic in nature, always seeking contradictions – good events may have bad outcomes, failures can end up with successes. The Chinese revolutionaries took to communism because of the Marxian dialectic methodology that resonated with the Taoist correlative world view.

Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilisations is about zero-sum game thinking, in which one civilisation’s gain is the other’s loss. The Chinese approach searches more for the win-win “dialogue of civilisations” in which competitors cooperate even as they compete, like Darwinian co-evolution of competing species.

The Chinese world view is not the only competitor to the West. Within the next few decades, the Indian world view will advance as South Asia, with a population of more than 1.8 billion, rises. So will the Islamic world view, which has more than 1.5 billion followers. Each will identify with their own exceptionalism. These multipolar networks of power will inevitably challenge the US unipolar paradigm.

If you really want to understand how Chinese within and outside the country think, read T. L. Tsim’s new novel Between Two Shores, the best political whodunnit by a Chinese writer in English that I have read for years. Enjoy the holidays and kung hei fat choi!

Andrew Sheng is a former central banker and financial regulator. The views expressed here are entirely his own