Inner & Outer Dimensions of Sound

It is now widely known, that Vajrayana—in Tibet and the other Himalayan and trans-Himalayan countries—evolved forms of liturgical chanting of unusual power and subtlety. These forms spread into Mongolia, China, and even the Russia Buriatya region around Lake Baykal. We speak of ‘Tibetan Buddhism’ now, as a matter of course in the West – but really this term is not an entirely accurate one. Although Tibet and the other areas which practice Vajrayana Buddhism were highly influenced by a staggering number of Tibetan masters, only Bhutan now remains as a free country with Buddhism as its national religion. We cannot change the name Tibetan Buddhism to Vajrayana, because all these countries practice the entire scope of the yanas. Vajrayana is simply what they all have in common, in terms of distinguishing them from the Buddhism which exists in other parts of the East, and it is Vajrayana which has given us such an inordinately rich heritage of liturgical chant.

The Gelug monks of the Gyütö Tantra College are now so famous for their ‘Bull’s Roar’ chanting style, that the ‘new age’ has cashed in on what has been falsely assumed to be the deliberate use of vocal augmented harmonics. This, in ‘new age’ parlance, is referred to as ‘over-tone’ chanting. Many people now imagine that merely producing these so-called ‘overtones’ has some spiritual benefit in itself – quite divorced from liturgical recitation and visualizations. So people now accomplish the art of chanting meaningless syllables to impress their friends at dinner parties and similar spiritual gatherings. This sad example of ‘new age’ spiritual materialism is a continuation of almost a century of projecting phantasy on to Tibetan and Vajrayana culture. This trend began with the theosophists and continued, through Madam Blavatsky and Alice Bailey, to ‘Lobsang Rampa’ – a plumber from Plymouth who took over where they left off. We were then treated to a book of fictitious ‘Tibetan physical exercises’, and the invention of ‘the Tibetan singing bowl’ which spawned such a boom in the metal industry in Taiwan, that the stalls of Kathmandu have been piled high with ‘Tibetan singing bowls’ for a decade.

I hope that this short talk on Tibetan Tantric music will help to provide a little fundamental information against which other more unlikely ideas can be measured. The ‘Bull’s Roar’ style of chanting I mentioned, is actually one with which I am somewhat familiar, so I will begin by discussing it a little – in order to dispel some of the fictions which have grown up around it. In my early twenties I practiced Vajrabhairava sadhana with the Gyüdtö monks. I had received Vajrabhairava empowerment from Song Rinpoche, a great Gelug Lama now sadly departed. I was encouraged to join the Gyüdtö monks in practice by Song Rinpoche, and the practitioners of Gyüdtö were kind enough to welcome me. One of their number, Thubten Dadak, who was of Nyingma parentage particularly befriended me. He served me in the capacity of translator on several occasions and we often discussed the meanings of the English words which were then in vogue for translating Tibetan terms. He was a very helpful, kind friend and I owe him a great deal in terms of the time he gave me.

At that time, the Gyüdtö monks practiced in a dilapidated shed with a packed-earth floor. The door and roof were simple wooden frames upon which flattened oil cans had been nailed. In the winter rains we could hardly hear our own voices for the drumming of the rain on the roof, so the famous ‘mystical overtones’ were often impossible to hear. It is now a little-known fact that the Gyüdtö monks do not actually try to produce these ‘overtones’ – they are simply an accidental side-effect of chanting very deeply. It used to be a relatively common practice for young Gyüdtö monks to force hemp rope down their throats to deepen their voices. Whether this custom is still widely practiced, I do not know. I never enquired for myself with regard to cultivating a better bull’s roar, as I was somewhat uncertain about the idea. However I found, through regular practice at Gyüdtö, that I could reach the low notes; and, although I never achieved any appreciable volume in that vocal range, it had a sufficient effect on my voice to significantly improve my ability to sing ‘Yang’. I am alas still a baritone [laughs] much to the chagrin, I am sure, of those tenor and soprano students who valiantly attempt to follow me in chanting and singing.

There are numerous different styles of chant (dönpa – don pa) of which I could speak, and Phüntsog Rinpoche has kindly invited me to talk with you about Yogic Song in Dzogchen, and particularly within the Aro gTér lineage. So let us begin with yang.

Yang (dByangs) or Dzogchen Gardang (rDzogs chen sGar gDang) is one of the major methods within the Aro gTér lineage. The Dzogchen method of Yang involves finding the presence of awareness in the dimension of sound. Yang differs considerably from liturgical chanting or dönpa – so it is important to be able to distinguish their contrasting principle and function if one is to establish a true understanding of the use of voice in Dzogchen practice. Yang, as the Dzogchen practice of finding the presence of awareness in the dimension of sound, is radically different from dönpa. Although Tibetan liturgical chanting exists in distinct contrast to Tibetan folk music—with regard to its principle and function, as well as to its modality and style—there are Dzogchen styles of ‘singing’ which closely resemble folk music. It is for this reason that criticism has historically been levelled at the Nyingmas in particular.

Phüntsog Rinpoche: Yes [laughs]. The Drigungpas and Drukpas have also been accused [laughs].

Ngak’chang Rinpoche: Some factors amongst the newest Tibetan monastic trend have charged us with being the Buddhist equivalent to the guitar-playing Christian clergy. Popularist motivating has been credited to Dzogchen yang on the basis that is resembles folk music more closely than the more monotone styles of the monastic environment in which a sharp distinction is made between sacred and profane. It is for this reason, amongst others, that we cannot make statements about Tibetan sacred music which are too ‘tightly definitive’. Close study of the Tibetan spiritual culture eventually highlights the fact that there are many exceptions to the rule.

For example, I have heard it stated that solo singing did not exist in Tibetan sacred music, and that multiple voice chanting was the sole distinguishing vocal characteristic. However, in the Dzogchen traditions solo singing is actually quite common. In fact it should be evident that there can be no alternative to ‘solo singing’ for any yogi or yogini in solitary retreat, whether they are monastic or non-monastic, celibate or non-celibate. This is especially true of gÇodpas and gÇodmas who often travel alone. Even in ngak’phang dratsangs where members of the gö-kar-chang-lo’i-dé practiced together, there existed solo voice renditions of Dzogchen yang by great masters. Such solo singing was performed in the context of both transmission and of inspirational song. Individually performed inspirational songs were often sung by yogis and yoginis as an aspect of tsog ’khorlo (tshogs kyi ’khor lo – gana chakra) – a symbolic practice involving the offering and sharing of food and wine.

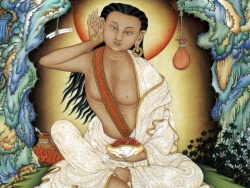

Phüntsog Rinpoche: Milarepa is a great example of solo singing.

Ngak’chang Rinpoche: Yes indeed – as was Shabkar. If one reads the namthars of the great Lamas of all schools one finds the spiritual songs they sang to their disciples.

The Vajrayana repertoire contains many different formulations. It differs so radically from Western musical forms, that even musicologists with knowledge of oriental forms are not well equipped to describe its peculiar dynamics. The origins of Tibetan sacred music are not easy to trace. The Tantras relate that sacred music originates in the Yang of the khandros and pawos (mKha’ ’gro and dPa bo – dakas and dakinis) The word yang, as it is used here, is said to relate to the Sanskrit word sarasvati (auspicious intonation) which was the style of chanting employed at the time of Buddha Shakyamuni, but it has a meaning in the Dzogchen traditions which is quite distinct from the liturgical meaning within Sutra and Tantra. As I said previously, the word for the liturgical recitation chants is dön. The term dön-ta (’don rTa) is used to denote the way in which the meaning of the liturgy is ‘conveyed’ by the rTa (horse) of the tune. In both monastic and non-monastic liturgical settings, melodies are employed as aids to memorise texts. Monks and nuns, upon entering a monastery—and ngakpas and ngakmas, upon entering ngak’phang dratsangs—are initially instructed to engage in the memorization of texts, through hearing and repeating the body of liturgical material in use at their gompa or ngak’phang dratsang.

When I was at Gyüdtö in McLeod Ganj in the early 1970s, every monk was required to attain competence in liturgy, and if a monk failed in developing the required ‘dzo’ of voice, he could expect to be expelled. None ever were to my knowledge – but it was evident that they applied themselves rigorously. All the Gyüdtö monks participate in chanting, because their education and symbolic knowledge depend upon the experience of performing Tantric rites. Chanting and the memorization of texts is a prerequisite to progress within the monastic systems of all schools, and is therefore central. Books in the Vajrayana culture were not easy to access – they were extremely valuable and it was therefore expedient to memories everything required for one’s practice. This is something which Khandro Déchen and I advise to all our students – and they find it valuable not to be encumbered by too much Xeroxed material [laughs]. However our repertoire, both sung and chanted, is relatively minimal.

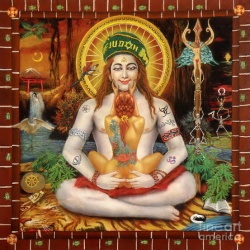

Chanting texts is intended to create a largo effect of one chanting in order that practitioners can get a handle on what it is that they are contemplating. The meaning of words is crucial here. Because of this, recitation is not always melodic. Tantric music is often employed as it serves to ‘disorientate’ the liturgist with regard to his or her dualistic orientation. Tantric instrumentation effects practitioners’ perceptual states in such a way as to render them more receptive to the functional energy of the practice. This practice of liturgical ritual ‘drüpthab’ (sGrub thabs – ‘method of accomplishment’ or ‘sadhana’ in Sanskrit) involves one’s self-generation as the yidam – the meditational deity, wisdom being, or awareness being. Drübthab involves tantrikas visualising themselves arising in the form of the yidam with the aid of music and the chanted text.

In the Buddhist Tantras, yidams demonstrate the nondual state in terms of specific qualities which act as catalytic impulses within each practitioner. Within the Sutras compassion for the suffering of dualised beings is expressed through the performance of monastic music, because music is said to produce happiness. It is therefore not simply an offering to the Lama, Sang-gyé, Chö, and Gendün (Guru, Buddha, Dharma and Sangha) but a means of nourishing everyone and everything everywhere. In terms of Sutra, this means that a chanting monk or nun can ‘gain merit’ due to the enjoyment of his or her listeners.

The Sutric teachings also maintain that human karmic vision of scared music is limited. The Sutras divide sacred music into ‘outwardly evident’ and ‘internally projected’ music. While practitioners are chanting or playing their instruments, they should simultaneously produce internal music in order to authenticate the inner mandala of the yidam.

The seventh Dalai Lama, Kelsang Gyatso (sKal bZang rGya mTsho – 1708-1757), whilst circumambulating the roof of the Potala, saw a minion of the protector Gönpo chag-druk nakpo (the six armed Mahakala) dancing in the sky. The seventh Dalai Lama sent an attendant to discover what was manifesting below. His attendant made his way down to the main chanting hall – but it was empty. There was merely a solitary dishevelled old yogi in worn-out monastic robes. He was sitting in the entrance tapping a stone rhythmically on the steps. The Dala’i Lama’s attendant asked: "What are you doing here?" and the old yogi (who turned out to be a former Gyütö monk) said: "In Gyütö, at this time of day, we play Tantric music and as I cannot be there I’m just nostalgically tapping this stone on the step and imagining the music." When the Dala’i Lama was told of this, he exclaimed: "Mahakala is dancing in the mind of that old yogi."

The function of Tantric music (which is internally projected but not outwardly evident) is that for the practitioners, the inner dimension of the Tantric music performed is of greater power than the outer dimension of its audible aspect. This inner aspect relates to Mind – as in ‘body, voice, and Mind’.

Body is represented by the Tantric instruments.

Voice is the corporeal sound energy.

Mind is the space in which inner non-dual music-display performs itself.

The most widely know spiritual practice in Vajrayana cultures was the calendar of group assemblies either in monasteries, ngak’phang dratsangs, or within the yogic gars – such as the Aro Gar. The Tantric music at these assemblies would range between spoken recitation, and forms which are increasingly musical according to school, lineage, and individual tradition. The Nyingma assemblies tended to favour the most melodic forms – as did the Drigung and Drukpa Kagyuds.

Phüntsog Rinpoche: Yes – that is because they most closely resemble the Nyingmapa in their beautiful liturgical melodies.

Ngak’chang Rinpoche: They also hold many practices in common, as well as having a rich gTérma tradition.

Phüntsog Rinpoche: Yes – and that is particularly true of the Drigung School.

Ngak’chang Rinpoche: Each school, tradition, and lineage —each monastery, ngak’phang dratsang and yogic gar—had its own specialised Tantric music. The main body of Tantric practice differed, but usually contained a cycle of Lamas, yidams, and chökyong/srungma (chos sKyong and srung ma – male and female protectors) which drew on the teachings of particular lineage Lamas. Tantric music was usually categorised in terms of the yidams and protectors they addressed. Tantric rites include Tantric music which expressed the nature of the focal Lama, yidam, khandro/pawo, or protector (bLa ma, yi dam, mKha’gro/dPa bo and chos sKyong/srung ma).

The rite performed in the visualisation of peaceful yidams is called as shi-wa (zhi ba). The style of shi-wa is slow and graceful. Liturgical changes from one section of a drüpthab text to another are exact and smooth. Peaceful instruments include: sil-nyen (sil sNyan), gyèling (rGya gLing); ting-sha (mthing chak); drums (chö-na – chos nga), and conch horns (dung – gDung) – although in the Aro gTér tradition the conch horn and ting-sha also have ‘wrathful’ functions.

The rites performed in the visualisation of joyous yidams is called as Ga-wa (dGa ba). The style of ga-wa is melodic and embellished. Joyous instruments include: sil-nyen, gyèling; ting-sha; drums, conch horns, and shang lang (shang lang) which are a cross between a cymbal and a bell. The shang is mainly used by the Bön tradition but it also has Buddhist uses. Also of interest is the large mélong (me long – mirror) – which is not actually an instrument, but is used as such in the music of Kurukula (Rig ye-ma – rig byed ma) where it is struck gently with a wooden stick like a pestle. When played together, these mélongs produce a whirring hum (kyu rur ru). The copper or silver version of the human bone trumpet (kangling – rKang gLing) is also used for the practice of joyous yidams in certain cases.

The Tantric music performed in the visualisation of wrathful yidams and protectors is know as drak-po (drag po). Wrathful yidam and protector practice demands a strong powerful voice with rough intonation. Wrathful instruments (played loudly and brashly) include: cymbals (rolmo – rol mo) or bub’chal (sBub ’chal); large cymbals (bub-chen – sBub chen); human bone trumpets, large drum (nga-chen – sNga chen); skull drum (töd-nga – sTod nga); large damaru (gÇod nga); and long horns (dungchen – rDung chen or radong – rag dung).

Sometimes wrathful Tantric music is performed, accompanied by hurling gTormas, in order to dispel demonic influence. This type of Tantric music needs to be powerful and continuous, and its efficacy can be judged according to whether those who hear it feel sufficiently nervous.

The styles of Tantric music are written down in a form of notational script called yang-yig (dbyangs yig). Although there are different forms of yang-yig belonging to the different traditions, each type functions in a similar way. They are suggestive rather than specify. Yang-yig accomplishes this through complex sequences of curved lines which occasion ‘movements’ – guiding the voice through the modulations of each syllable.

In some yang-yig linguistic annotations suggest the texture or physique of the vajra melody. Such annotation in the Dzogchen style suggests that the voice should: fly like a vulture; soar like an eagle; rise in space like the garuda; flow like a river in spate; crash like a mountain torrent, or be as light as the twittering of a bird.

Within such notations there are often apparently ‘meaningless’ syllables, and it has been suggested by certain naive persons that these extra sounds are a device for the purpose of deliberately obscuring meaning. This quaint idea would have us believe that those without authentic transmission and authorization are thereby foiled in their attempt to delve ‘mysteries’ for which they are unprepared. Such ideas owe more to the over-active imagination than to the subject of yang-yig. These words are actually mantric syllables and although often secret, they are not used to cause obfuscation. These extra sounds facilitate the often protracted melodies of yang, particularly in the case of Dzogchen yang.

Phüntsog Rinpoche: There are many types of voice used in chanting and singing. Could you speak about them?

Ngak’chang Rinpoche: Yes – in some systems each is specified according to its origin within the body. There is ‘physical-space voice’ (khog-pa’i kè – khog pa’i sKad); ‘throat voice’ (grin-kè – mGrin sKad); ‘nasal voice’ (na-kè – sNa sKad); ‘male voice’ (po-kè – pho sKad); ‘female voice’ (mo-kè – mo sKad); and ‘neutral voice’ (ma-ring-kè – ma ring sKad). In the Aro gTér we have what is called ‘Self-voice’ meaning ‘natural voice’ or ‘of-itself voice’ (rang-kè – rang sKad.)

Phüntsog Rinpoche: There are as many as thirteen instruments which can be played together at any one time.

Ngak’chang Rinpoche: Yes – these are often divided into four categories: rung or chimed instruments, stringed instruments, blown instruments, and beaten instruments.

Rung or chimed instruments enrich the texture of the Tantric music.

Stringed instruments inaudibly insinuate serenity.

Blown instruments (those which play melodies) dramatise.

Beaten instruments dominate the basic structure.

Within the Aro gTér tradition, these modes are linked with the four Buddha-karmas of enriching, pacifying, magnetising, and destroying. The Tantric orchestra can include two chö-nga (damarus) with two bells; two stick drums; two sets of gyèlings; two kanglings; two long horns (dung chen); and two conches.

The rolmos are played in a both clockwise and anti-clockwise semi-revolutions, which makes use of their harmonics producing astonishing effects. The stick drums are played with sticks formed into the shape of ‘question marks’. Rolmo and stick drums lead the Tantric orchestra and create its rhythmic direction – the other instruments usually only augment. The rhythms of the drums and bells do not accord with Western concepts of musical tempo. There are no evenly measured temporal assemblages. The timing is taken solely from the passage of the rite in question. Rhythmic assemblages often change in duration, and accelerate so that rhythm as such becomes unrecognisable. This lack of a compositionally coherent rhythm which separates time into equal measures is unique to Tantric music.

The dung-chen, which are often about six to nine feet long, can sometimes measure thirty feet long if they are played on monastery roofs. They have a range of over three octaves and produce sounds which are cavernous and seem to emanate from the vastness of space. Their reverberations are of such a physical magnitude that they have been known to loosen the dental apparatus of those who played them – to the point at which teeth have been known to fall out.

Special training is needed for the gyèlings and long horns as they require skill in circular breathing. That is why Khandro Déchen and I have introduced the use of the ‘three dungchen line up’. By this means three people can overlap to create a continuous sound. Rolmo, although seemingly simple to play, require many years of practice. Their subtleties are considerable and the many ‘feathering’ and ‘cork-screwing’ techniques are quite difficult to master. The rolmo are the responsibility of the um-dzé (dbU mBzad) – the master of chant and yogic song. He or she leads the performance of Tantric music and voice. He or she is the musical director. In the hierarchical divisions of spiritual leadership, the um-dzé ranks second below the Lama.

Each Vajrayana tradition has a cycle of Tantric music, but in contradistinction to other linguistic texts, yang were rarely carved into wooden printing blocks. Almost all musical notation and notation of yang-yig were hand-written and so much has been lost. The Aro gTér traditions of song, of course are all oral (oral/aural) and so they depend entirely on transmission. The ‘Flight of the Vulture’ for example, is now simply held by those who have learnt it and who practice it. There is much that I could say about the many vajra melodies of the Aro gTér tradition, and the way in which they were taught – but we have little time at the moment. As I showed you all earlier, the ‘Flight of the Vulture’ and the other bird sem-dzins of this kind, are taught through the use of mudras in which the thumbs touch and the fingers spread like wings. Through the use of this method the yang-yig is physically demonstrated rather than using a text – but that of course requires a continuing lineage of practitioners who can pass these things on.

Source

Teaching given at the request of Drigung Tsha-ug Dorje Lhokar Rinchen Phüntsog Rinpoche by Ngak’chang Rinpoche at ‘Drigung Phüntsog Chöling,’ Wien, Austria – May 1992

Aroencyclopaedia.org Part I

Aroencyclopaedia.org Part II