Jonang: The Struggle for Justice and Equality for Tibet’s Sixth Major Buddhist Tradition

“To prohibit the reading of certain books is to declare the inhabitants to be either fools or slaves.” – Claude Adrien Helvétius

‘It is reasonable that everyone who asks for justice should also do justice.’ -Thomas Jefferson

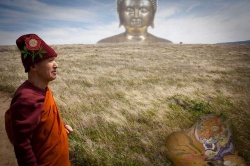

‘May they have pity on those who hold that the whole of the Buddha’s teaching on openness concerned self-emptiness alone….a non-affirming negation alone…..mere nothingness alone….non-appearance alone….total nothingness alone and hold them in their compassion.’ – Dolpopa

On 18th June 2015, the leaders of the five major Tibetan traditions and the Tibetan political leader in exile, Dr. Lobsang Sangay, gathered together for the 12th Religious conference on Tibetan Buddhism, the last one was held in 2011.

Absent from the meeting was any representation from the Jonang tradition.

This is surprising considering that at the last conference in 2011, it was unanimously agreed by all five traditions, at HH 14th Dalai Lama’s prompting, to formally recognize the Jonang as a separate lineage of Tibetan Buddhism.

It was also reported a month ago, that even though the Tibetan Parliament in Exile in Dharamshala, India had voted to give one-seat parliamentary representation to Tibetans living in Australasian and Asian countries other than India, Nepal and Bhutan, the Jonang Buddhist tradition, failed to get enough votes for separate parliamentary seats.

Currently, ten members are elected from each from region: U-Tsang, Amdo and Kham, the three traditional provinces of Tibet, while the four schools of Tibetan Buddhism, Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, Gelug and the indigenous Bon religion elects two members each.

Four members are elected by Tibetans outside Asia, two from Europe, one from North America and one from Canada.

According to one report, Jonang supporters gathered outside the parliament to protest against the result:

‘Speaker of the Parliament, Penpa Tsering, answered the letter that was handed out by the demonstrators saying the matter has been discussed in the Parliament over the years.

Tsering made the remarks in his concluding speech of the Parliament session.

He said that he tabled the issue in the House but not many members debated it, and hence there was no outcome. He also said that there was no scope to discuss it now, on the last day of the session, indicating that it could be discussed in future sessions if enough members were interested and supported it.’

Putting aside the issue as to whether or not Tibetan democracy in exile should be fully secularised, considering the history of censorship, repression and conversion of Jonang by the Gelug and Mongol ruling authorities since the 17th Century, it is a disappointing response for the Jonangpas who have been petitioning for separate representation over a number of years.

In addition, the historical evidence, as well as renowned contemporary scholars such as Nyingma master, Khenpo Tsultrim Lodro, clearly indicate that Jonang are the protectors and holders of the philosophically profound Zhentong view of Ultimate Reality (or Buddha Nature) and the sole unbroken lineage holders of the complete Kalachakra teachings and practices in Tibet.

As one contemporary Jonang master put it:

‘“As a Tibetan I feel rather embarrassed that this is even an issue. Within Tibet, the Tibetan community has recognised the Jonang as a unique and major tradition for 800 years.

Even the Chinese Government gives them the same rights as they do the other traditions.

In 2011, the religious leaders of all the Tibetan traditions in exile gathered and also officially recognised the Jonang as a separate tradition.

We have been working for 18 years to shed light on this situation but still there have not been any substantial results.

As time goes on, the situation deteriorates causing greater division and disunity within the community itself in a time when we need the exact opposite.”

Censorship and Repression in 17th Century Tibet

There is a prevailing ideology not only in the Tibetan exile community but also among many of their western, liberal supporters that prior to the Chinese invasion, Tibet was a peaceful, non-violent Buddhist country.

Yet, even a cursory study of Tibetan history and scholarship on this subject will reveal a more complex and problematic picture.

Nowhere is this more obvious when considering the conversion and censorship of the Jonangpas in 17th Century Tibet.

There have been several recent works of scholarship by eminent scholars that challenge the mainstream narrative of how and why the Fifth Dalai Lama and the Gelugpa became so powerful in Tibet during that era.

Although there is not enough space to do justice to the complexity and depth of the history and intellectual thought of Jonang here, I will give a brief summary.

The Jonangpa tradition was founded in 1027 A.D. with a distinct philosophical viewpoint on the nature of reality often referred to as Zhentong (empty of other).

Kungpang Thugje Tsondue (1243-1313 A.D.) founded a monastery in Jomonang in U-tsang, and it became known as Jonang Monastery.

The tradition was further systematised and promoted by Kunkhyen Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen (1292-1361 A.D), the founder of the Middle-Way School of Zhentong, of both Sutra and Tantra.

Dolpopa was one of the most important and original thinkers in Tibetan history, and perhaps the greatest expert on the tantric teachings of the Kalacakra, or Wheel of Time.

He was born in the Dolpo region of modern Nepal but in 1309, when he was seventeen, he ran away from home to seek Buddhist teachings, first in Mustang, and then in Tibet.

He is considered to be one of the greatest exponents of the Kalachakra or Wheel of Time and a consummate practitioner of the Six Yogas, the perfection stage practices of the Kalacakra Tantra.

Although he based his doctrinal discussions upon scripture, in particular the Kalacakra related cycles, his own experience in meditation was crucial to the formulation of his theories.

Dolpopa was publicly and overtly critical of Rangtong (Empty of Self) interpretations of the fundamental nature of reality. Rangtong being the view predominantly held and propagated by Gelugpas:

“For a long time my mind was also accustomed to the habitual propensity for that well-known [view].

Even though I did understand a small amount of Dharma, for as long as I had not behled the great kingdom of the exceptional, profound, uncommon and sublime Dharma, I also merely relied upon the verbal regurgitation of others and said,

“Only an emptiness of self-nature fits the definition of emtpiness, there is no definition of emptiness beyond that, ” and so forth, as was mentioned above. Therefore, it is not the case that I do not also understand that tradition.

At a later time, due to the kindness of having come into contact with The Trilogy of Bodhisattva Commentaries, [I understood] many profound and extremely important points of Dharma which I had not understood well before….Now, if I think about the understanding at that time, and the corresponding statements I made, I am simply mortified.” (Stearns (1999), p85)

In 1642, seven years after the death of Taranatha ( another Jonang master), an alliance of Mongol armies led by Gushri Khan defeated the Tsang rulers and enthroned the Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (1617-1682).

According to most historical accounts, in the year 1650, the Fifth Dalai Lama sealed and banned the study of Jonang Zhentong texts, prohibiting the printing of such texts throughout Tibet.

Then in 1658, the Jonang Takten Damcho Ling (Phuntsok Choling) Monastery (built by Taranatha near the original site of Jonang) was forcibly converted into a Geluk Monastery — officially initiating the demise of the Jonangpa in U-Tsang.

The carving of the blocks came to an end, the printing of impressions from the blocks stopped, and the recognition of the re-embodiment of the Jonang Jetsun prohibited.

All of the Jonang monasteries and hermitages in central Tibet were seized and the remaining Jonang masters in the area began an exodus to previously established monasteries in the remote regions of Tibet.

As Gene Smith states in Banned Books in the Tibetan-Speaking Lands (2004), it was not just the Jonang who were affected by such draconian measures:

‘Most examples of Tibetan banned literature involved controversies in philosophical teachings beginning in the 11th century.

Philosophical positions such as the gZhan stong, (the Void of the Other) became regarded as heretical and many of the greatest masters of the Gelug tradition were branded as proponents and their works set aside and not permitted to be read or copied.

Great teachers such as Jamyang Choje, the founder of the famed Gelug monastery of Drepung and Lotro Rinchen Senge, the founder of Sera Je, were banned.

The early Gelugpa school slowly calcified and core syllabi replaced honest debate and disputation.

It was, however, only in the 17th and 18th century that there was a wholesale ban placed on the most famous writings of traditions, such as Jonang, Sakya, Kagyu, and Nyingma by the princes of the ruling Gelug tradition.

A survey of the existing blocks in Central Tibet was undertaken by the Tagdra regent in 1956.

This notes the existence of printing blocks, many of which were sealed, by order of the Government of the Ganden Podrang.

The list of the banned books included the works of such philosophical masters as Dolpopa, Taranatha, the Five Patriarchs of the Sakya, and Karma Mikyo Dorje.

Prohibitions against the striking of impressions of the Tagten Puntsoling Monastery of the Jonang was only lifted in the mid-19th century through the efforts of the the scholar Losal Tenkyong.’

Interestingly, the Jonangpa Foundation website states that once the Jonang teachers had been ‘uprooted’ and settled in Amdo, there was ‘no Geluk ban or prohibition’ against the Jonang or Shentong philosophical view.

Whether or not that is true, the narrative of this important era in Tibetan history has certainly been sanitised since the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama.

How should we view these events historically? As doctrinal and political censorship or as a necessary evil in the quest to unify Tibet? The mainstream ‘romantic’ narrative is the latter.

Many Tibetans believe or have been taught, rightly or wrongly, that the unification and stability of Tibet justified the violence and force that accompanied this ‘takeover’, labelling the Fifth Dalai Lama ‘Great’.

However, Derek Maher takes a different view in Sacralized Warfare: The Fifth Dalai Lama and the Discourse of Religious Violence (2010):

‘It is one thing to deploy Buddhist imagery and narratives to justify the defense of the interests of Buddhists being persecuted by some malevolent non-Buddhist oppressor; it is quite another to legitimize sectarian conflicts between Buddhists.

The [5th] Dalai Lama has a heightened sensitivity to this question, and he downplays the intrareligious basis of the most substantial warfare that took place leading up to the culmination of events in 1642.

The battle against Chog thu and the Beri chief were minor sideshows compared to the decisive battles that took place in dbU and gTsang between partisans of the Buddhist dGe lugs and bKa’ brgyud schools.

When the Dalai Lama reaches this part of the story, he merely mentions that Gushri deployed billions of troops and subjugated the land, but he makes no mention of who was defeated.

He further obfuscates matters when he concludes by remarking that the kings and ministers of Tibet had to learn to bow humbly to Gushri Khan in 1642. The Dalai Lama attempts to convey a tone of neutrality among Buddhists.

This tone is in stark contrast to the manner in which this series of events was perceived by others at the time and in the decades and centuries that followed. In the eyes of non–dGe lugs pas, Gushri Khan’s conquests and the ascendancy of the (Fifth) Dalai Lama as the paramount political force in the country were both permeated with sectarian agendas.

Monasteries were seized and converted, land estates were reassigned to support dGe lugs institutions, the Karmapa was driven into exile, and the entire symbolic universe was reconfigured to feature the institution of the Dalai Lama at its core.

The Fifth Dalai Lama wrote ‘Song of the Queen of Spring’ in an attempt to influence the way people perceived these conquests soon after they took place.’

It is highly likely that such conflicts were bloody and involved loss of life too. In 1660, (according to Ben Kiernan (2007)) the Fifth Dalai Lama wrote, referring to Tibetan rebels:

“Make the male lines like trees that have had their roots cut;

Make the female lines like roots that have dried up in winter;

Make the children and grandchildren like eggs smashed against the rocks;

Make the servants and followers like heaps of grass consumed by fire;…

In short, annihilate any traces of them, even their name.”

Newland (1992) conveys the political tension between the 5th Dalai Lama and the Jonangpa, the king of Tsang and the philosophy of Dolpopa (here referred to as Sherab Gyaltsen):

Tsong-ka-pa and his successors have been especially vehement in their objections to the views of Shay-rap-gyel-tsen, (shes rab rgyal mthsan, 1292-1361) and his followers. Shay-rap-gyel-tsen, an abbot of Jo-mo-nang, formulated his view in Ocean of Definitive Meaning (nges don rgya mtsho) and other writings; his followers are called Jo-nang-bas.

As Ge-luk political power reached its apogee under the Fifth Dalai Lama in the seventeenth century, the Jo-nang-bas were proscribed and their monasteries and other property were completely confiscated and converted to Ge-luk use.

Tibet’s intersectarian conflicts were almost always driven by motives more political than “purely philosophical”, indeed, the Jo-nang-bas were allies of the king of Tsang (gtsang), the main political and military adversary of Ge-luk in the first half of the seventeenth century.

On the other hand, for more than two hundred years before they destroyed the Jo-nang-ba order the Ge-luk-bas had been denouncing Shay-rap-gyel-tsen’s philosophy as something utterly beyond the pale of Mahāyāna Buddhism…While the immediate occasion for the persecution of Jo-nang was its defeat in a power struggle, proscription suggested itself as a penalty in the context of a long history of substantial and deeply felt philosophical differences.

This hostility is reflected in the banning of Shay-rap-gyel-tsen’s major books from the premises of Ge-luk monasteries more than 150 years prior to his order’s extinction.

According to Stearns (1999) and others, the survival of Zhentong philosophy in mainstream Tibetan society has largely been due to the influence of several great Nyingma and Kagyu masters from the Kham region of Eastern Tibet who came to accept and actively teach Dolopopa’s views.

People such as the Nyingma master, Katok Rikzin Tsewang Norbu, Situ Panchen, the Karmapas and Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye (who is best known as the progenitor of the Rimé project, an intellectual movement that sought to consolidate the living instruction lineages of Buddhism in Tibet in order to emphasize eclecticism and preserve these instructions for future generations).

Bon teacher Tenzin Wangyal (2000) cautions, however, that even this so-called non-sectarian attitude may be taken to an extreme:

A problem that seems very difficult to avoid involves the tendency of spiritual schools either to want to preserve their traditions in a very closed way or to want to be very open and nonsectarian; but there is often the danger that this very nonsectarianism can become a source of self-justification and lead to as closed an attitude as that of the sectarians.

Jonang in the 21st Century

One of the reasons cited as to why few people are aware of the Jonang, is the fact that they did not flee Tibet in 1959. So when the Tibetan Administration in Exile began registering traditions, the Jonang were absent.

Therefore, very few foreigners were ever introduced to their authentic teachings.

It was not until 1990 that the first Jonang monks began to emerge from Tibet. Since then they (and others) have been requesting the Tibetan society in exile to recognise their tradition as worthy of equal respect and acknowledgement.

Interestingly, one of the most visible and vocal non-Jonang supporters, is the 14th Dalai Lama himself. In late 2001, the Dalai Lama composed an “Aspiration Prayer for the Flourishing of the Jonang Teachings” (Tibetan:

ཇོ་ནང་པའི་བསྟན་རྒྱས་སྨོན་ལམ་, Wylie: Jo-nang pa’i bStan rGyas sMon-lam) which calls for the flourishing of Jonang teachings and view.

In 2010, the Jonang tradition inaugurated its first office in Dharamashala, the ‘Jonang Well Being Association in India’.

The Association aims to revive and spread awareness about the Jonang lineage.

Then, in 2011, the conference in exile that formally recognised the Jonang as a separate Tibetan Buddhist tradition.

So, reasons as to why the Tibetan exile authorities still do not treat Jonang as a separate and equal tradition (contrary to the decision of the Dalai Lama and other major lineage heads) or excluded them from the Tibetan Buddhist religious conference are unclear.

On the one hand, it has been suggested that the elected representatives who voted against it were all from Kham and were concerned that inclusion of Jonang would lead to imbalance between Amdo and Kham representation.

One Sakya representative, Zi Tsering po, claimed that the Jonang are a part of the Sakya tradition, which is bizarre considering all the lineage heads have agreed that the Jonang are a separate tradition.

Another reason cited is that if representation were given to Jonang then it would have to be given to Tibetan Shangpa, Muslims, Christians, Botong, and other minorities.

Yet such religious groups are nowhere near as philosophically or historically significant in Tibetan Buddhism as the Jonangpa, who number potentially one million. A Tibetan PhD student told me that:

There could be another reason, especially among youngsters (and therefore an immaterial one), who feel that at the age of political secularization (where religion and its representations in polity is on the retreat and seen more as anachronistic),

giving political seats and representations to yet another religious group in the political space is frowned upon.

I certainly feel that Jonang tradition, having gone through a terrible time in history, deserves recognition and rehabilitation in society and polity,

but at the time when one feels poltiical representations or seats in parliament to any religious sects is a hurdle to the achievement of full political secularization of Tibetan polity (i.e. no religious seats at all in the parliament), giving yet another political seats to Jonangpa tradition feels like a more hurdle in the process of attaining secular polity.

That’s how i felt when the issue of Jonangpa representation was raised in the parliament. Unfortunately, Jonangpas also have to deal with the exile political process of secularization.

I wish that the Jonang plight is brought open to the larger Tibetan public and made known to all, – ie their history, philsophy and their contribution to tibetan civilzation.

So, while some advances have been made in respect of giving reparation, justice and equality for the Jonangpas, unfortunately this work is still not complete.

The Jonang is a distinct and valuable lineage that has contributed much to Tibet’s philosophical and cultural heritage.

If the Tibetan exile authorities are serious about human rights, freedom and truth then they could start by ensuring justice and equality closer to home with the Jonang. As HH 14th Dalai Lama stated in his prayer:

You uphold and transmit an unparalleled oral transmission,

A commentarial tradition distinct from other sutras and tantra,

On the great chariot tradition of the Kalachakra Tantra.

May the teachings of the Jonang flourish!

Bibliography

Hookham, Shenpen (1991). ‘The Buddha Within: Tathāgatagarbha Doctrine According to the Shentong Interpretation of the Ratnagotravibhaga’, State University of New York Press, New York.Ishihama, Yumiko (1993) “On the Dissemination of the Belief in the Dalai Lama as a Manifestation of Bodhistattva Avalokitesvara.” Acta Asiatica 64: 38-56.

Hopkins, Jeffrey (2006). ‘Mountain Doctrine: Tibet’s Fundamental Treatise on Other-Emptiness and the Buddha Matrix’ by Dolpopa, Jeffrey Hopkins, Snow Lion Publications, Hardcover, 832 Pages.

Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur, (2007), p. 6, Yale University Press.

Karmay, Samten G. (December 2005). “The Great Fifth” (PDF). IIAS Newsletter Number 39. Leiden, The Netherlands: International Institute for Asian Studies. pp. 12, 13. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

Newland, Guy (1992). ‘The Two Truths: in the Mādhyamika Philosophy of the Ge-luk-ba Order of Tibetan Buddhism’. Ithaca, New York, USA: Snow Lion Publications.

Sheehy, Michael (2010). “The Jonangpa after Tāranātha: Auto/biographical Reflections on the Transmission of Esoteric Buddhist Knowledge in 17th Century Tibet.” in The Bulletin of Tibetology, 45.1. Gangtok, Sikkim: Namgyal Institute..

Smith Gene (2004). ‘Banned Books in the Tibetan Speaking Lands’, in: Symposium on Contemporary Tibetan Studies Collected Papers: 21st Century Tibet Issue. Taipei: Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission, 2004: 186–196. See also http://www.mtac.gov.tw/pages/93/Gene%20Smith.pdf.

Stearns Cyrus (August 2008). “Dolpopa Sherab Gyeltsen”. The Treasury of Lives: Biographies of Himalayan Religious Masters. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

Stearns Cyrus (1999). ‘The Buddha from Dolpo: A Study of the Life and Thought of the Tibetan Master Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen’. State University of New York Press.

Wangchuk Dorji (2014), ‘Biblioclasm/Libricide in the History of Tibetan Buddhism’, unpublished.

Wangyal Tenzin (2000), ‘Wonders of the Natural Mind: The Essence of Dzogchen in the Native Bon Tradition of Tibet’.