Jung’s Warnings Against Inflation

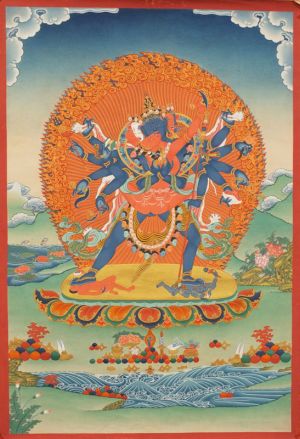

As we have seen, in deity yoga compassion and wisdom are combined in a single consciousness such that the mind of wisdom realizing emptiness is used as the basis from which oneself emanates as, or appears as, a deity. The mind of wisdom itself appears compassionately as a deity; the “ascertainment factor” of the consciousness realizes emptiness while the “appearance factor”b appears as an ideal being, whose very essence is compassion and wisdom.

Tsong-kha-pa singles out this practice of deity yoga as the central (but not the only) distinctive feature of Mantra. The Sūtra systems involve meditation that is similar in aspect to a Buddha’s Body of Attributes in that in meditative equipoise directly realizing emptiness the Bodhisattva’s mind realizing emptiness is similar in aspect to a Buddha’s exalted knowledge of the mode of being of phenomena in its aspect of perceiving only the ultimate, emptiness. However, the

Sūtra systems do not involve meditation similar in aspect to a Buddha’s form body, in that the meditator does not imagine himself or herself to have a Buddha’s physical form, whereas such does occur in Mantra. Thus, for Tsong-kha-pa, visualizing oneself as a deity and identification with that deity comprise the central distinguishing feature of tantric meditation. In descriptions of the distinctiveness of Mantra in other orders of Tibetan Buddhism also, deity yoga is a distinguishing feature of Mantra but is not singled as out as the central difference.

On the surface, Carl Jung’s warning that inflation necessarily attends identifying oneself with an archetypal motif would seem completely applicable to the practice of deity yoga. His cautions are profound and serve to highlight the enormity of the task that the tantric systems are attempting. Jung frequently warns against the inflation attendant upon assimilation of autonomous complexes and identification with their content, as, for instance, when he says: It will be remembered that in the analysis of the personal unconscious the first things to be added to consciousness are the personal contents and I suggested that these contents which have been repressed, but are capable of becoming conscious, should be called the personal unconscious. I also showed that to annex the deeper layers of the unconscious, which I have called the collective unconscious, produces an extension of the personality leading to the state of inflation.

Jung feared the perils of inflation that he found in Westerners who attempted Eastern yoga. To counteract this, he stressed assimilation of contents of the collective unconscious, not through identification, but through confrontation, wisely avoiding equation with either the lowest or highest aspects of one’s own psyche. This Tibetan system, however, stresses the importance of “divine pride,” in which the practitioner seeks to develop such clear imagination of herself or himself as a deity that the sense of being a deity occurs strongly (though not to the point of utter conviction). As we have seen in the previous chapter, in Action Tantra this practice begins with emptiness yoga, called the “ultimate deity,” and the deity is an appearance of the wisdom realizing the emptiness of inherent existence—the deity being merely the person designated in dependence upon purely appearing mind and body. Because the empty status of the person is being realized, it is said that deity yoga serves even to counteract the conception of oneself as inherently existent and thereby to prevent afflicted pride, a version of egoinflation which Jung sought to avoid by advising against identifying with assimilated contents.

In exploring these issues, let us first consider Jung’s very sensible and profound warnings and then whether any of the specific steps in the practice of deity yoga in Buddhist Tantra could serve to prevent inflation. I find Jung’s framing of the issue to be profoundly stimulating, serving as a foil for appreciating the significance of deity yoga.

Jung’s warnings

To Carl Jung it is by no means so simple. This can be seen when he speaks of great dangers in Westerners’ attempting the Eastern yoga which, for him, is amoral but is misinterpreted in the West as a pretext for immorality:a

Anyone who affects the higher yoga will be called upon to prove his professions of moral indifference, not only as the doer of evil but, even more, as its victim. As psychologists well know, the moral conflict is not to be settled merely by a declaration of superiority bordering on inhumanity. We are witnessing today some terrifying examples of the Superman’s aloofness from moral principles.

I do not doubt that the Eastern liberation from vices, as well as from virtues, is coupled with detachment in every respect, so that the yogi is translated beyond this world, and quite inoffensive. But I suspect every European attempt at detachment of being mere liberation from moral considerations. Anybody who tries his hand at yoga ought therefore to be conscious of its far-reaching consequences, or else his so-called quest will remain a futile pastime. Such misapplication of yoga leads to positive and negative inflation and all their attendant ills of which Jung speaks repeatedly and eloquently throughout his works.

For instance:

In projection, he vacillates between an extravagant and pathological deification of the doctor, and a contempt bristling with hatred. In introjection, he gets involved in a ridiculous self-deification, or else a moral self-laceration. The mistake he makes in both cases comes from attributing to a person the contents of the collective unconscious. In this way he makes himself or his partner either god or devil. Here we see the characteristic effect of the archetype: it seizes hold of the psyche with a kind of primeval force and compels it to transgress the bounds of humanity. It causes exaggeration, a puffed-up attitude (inflation), loss of free will, delusion, and enthusiasm in good and evil alike.

Positive inflation of the religious sort can lead to assumptions of grandeur, viewing oneself as having the universal panacea:c

a Collected Works, vol. 11, para. 825-826. b Collected Works, vol. 7, para. 110. c vol. 7, para. 260.

The second possible mode of reaction is identification with the collective psyche. This would be equivalent to acceptance of the inflation, but now exalted into a system. In other words, one would be the fortunate possessor of the great truth that was only waiting to be discovered, of the eschatological knowledge that means the healing of the nations. This attitude does not necessarily signify megalomania in direct form, but megalomania in the milder and more familiar form it takes in the reformer, the prophet, and the martyr.

Just as the prophet convinced that he/she has the final truth is inflated through identification with the forces of deep contents, so is the humble disciple, affecting the posture of only following the master’s dictums:a

But besides the possibility of becoming a prophet, there is another alluring joy, subtler and apparently more legitimate: the joy of becoming a prophet’s disciple.…The disciple is unworthy; modestly he sits at the Master’s feet and guards against having ideas of his own. Mental laziness becomes a virtue; one can at least bask in the sun of a semidivine being.…Naturally the disciples always stick together, not out of love, but for the very understandable purpose of effortlessly confirming their own convictions by engendering an air of collective agreement.…[J]ust as the prophet is a primordial image from the collective psyche, so also is the disciple of the prophet.

In both cases inflation is brought about by the collective unconscious, and the independence of the individuality suffers injury.

In a similar vein:b

These few examples may suffice to show what kind of spirit animated these movements. They were made up of people who identified themselves (or were identified) with God, who deemed themselves supermen, had a critical approach to the gospels, followed the promptings of the inner man, and understood the kingdom of heaven to be within. In a sense, therefore, they were modern in their outlook, but they had a religious inflation instead of the rationalistic and political psychosis that is the affliction of our day.

Jung’s description of his own time as being under the sway of a “rationalistic and political psychosis” in which gathered libido is invested in rationalism as a cure-all and is invested in politics as a panacea for all ills prompts me to add that today such inflation is also found in excessive concentration on economics, such that the focus of improvement is on the level of personal income and the gross national product with personal fulfillment being almost forgotten.

Too much attention is turned to externals, as if proper social, political, and economic arrangements would cure our situation. Jung advises against identifying with offices and titles since such excludes the richness of our situation:

A very common instance is the humorless way in which many men identify themselves with their business or their titles. The office I hold is certainly my special activity; but it is also a collective factor that has come into existence historically through the cooperation of many people and whose dignity rests solely on collective approval. When, therefore, I identify myself with my office or title, I behave as though I myself were the whole complex of social factors of which that office consists, or as though I were not only the bearer of the office, but also and at the same time the approval of society. I have made an extraordinary extension of myself and have usurped qualities which are not in me but outside me.

And:

There is, however, yet another thing to be learnt from this example, namely that these transpersonal contents are not just inert or dead matter that can be annexed at will. Rather they are living entities which exert an attractive force upon the conscious mind. Identification with one’s office or one’s title is very attractive indeed, which is precisely why so many men are nothing more than the decorum accorded to them by society. In vain would one look for a personality behind the husk. Underneath all the padding one would find a very pitiable little creature. That is why the office—or whatever their outer husk may be—is so attractive: it offers easy compensation for personal deficiencies.

The basic problem is that one has lost a healthy respect for the need to mediate between the conscious and the unconscious, thereby (in one version) inflating the importance of the ego:a

To the extent that the integrated contents are parts of the self, we can expect this influence [of assimilation] to be considerable. Their assimilation augments not only the area of the field of consciousness but also the importance of the ego, especially when, as usually happens, the ego lacks any critical approach to the unconscious. In that case it is easily overpowered and becomes identical with the contents that have been assimilated.…I should only like to mention that the more numerous and the more significant the unconscious contents which are assimilated to the ego, the closer the approximation of the ego to the self, even though this approximation must be a never-ending process. This inevitably produces an inflation of the ego, unless a critical line of demarcation is drawn between it and the unconscious figures.

The problem of inflation occurs whether the ego is drowned in the larger self or the larger self is pretentiously assimilated to the ego:b It must be reckoned a psychic catastrophe when the ego is assimilated by the self. The image of wholeness then remains in the unconscious, so that on the one hand it shares the archaic nature of the unconscious and on the other finds itself in the psychically relative space-time continuum that is characteristic of the unconscious as such.…Hence it is of the greatest importance that the ego should be anchored in the world of consciousness and that consciousness should be reinforced by a very precise adaptation. For this, certain virtues like attention, conscientiousness, patience and so

forth, are of great value on the moral side, just as accurate observation of the symptomatology of the unconscious and objective self-criticism are valuable on the intellectual side. However, accentuation of the ego personality and the world of consciousness may easily assume such proportions that the figures of the unconscious are psychologized and the self consequently becomes assimilated to the ego. Although this is the exact opposite of the process we have just described it is followed by the same result: inflation.

Correspondingly, inflation is of two varieties, negative and positive, the former being when the ego is subsumed in the collective unconscious and the latter when the ego takes too much to itself.

Jung says:

With the integration of projections—which the merely natural man in his unbounded naïveté can never recognize as such—the personality becomes so vastly enlarged that the normal ego-personality is almost extinguished. In other words, if the individual identifies himself with the contents awaiting integration, a positive or negative inflation results. Positive inflation comes very near to a more or less conscious megalomania; negative inflation is felt as an annihilation of the ego.

Jung frequently makes clear his position that one must negotiate the passage between the Scylla and Charybdis of the needs of unconscious contents to manifest and the imperative of effective individuation. For example, he says,b “The unconscious can only be integrated if the ego holds its ground,” and:c If our psychology is forced, owing to the special nature of its empirical material, to stress the importance of the unconscious, that does not in any way diminish the importance of the conscious mind. It is merely the one-sided over-valuation of the latter that has to be checked by a certain relativization of values. But this relativization should not be carried so far that the ego is completely fascinated and overpowered by the archetypal truths. The ego lives in space and time and must adapt itself to their laws if it is to exist at all. If it is absorbed by the unconscious to such an extent that the latter alone has the power of decision, then the ego is stifled, and there is no longer any medium in which the unconscious could be integrated and in which the work of realization could take place.…Against the daemonism from within, the church offers some protection so long as it wields authority. But protection and security are only valuable when not excessively cramping to our existence; and in the same way the superiority of consciousness is desirable only if it does not suppress and shut out too much life. As always, life is a voyage between Scylla and Charybdis.

He identifies the two perils eloquently:a

Even when the conscious mind does not identify itself with the inclinations of the unconscious, it still has to face them and somehow take account of them in order that they may play their part in the life of the individual, however difficult this may be. For if the unconscious is not allowed to express itself through word and deed, through worry and suffering, through our consideration of its claims and resistance to them, then the earlier, divided state will return with all the incalculable consequences which disregard of the unconscious may entail. If, on the other hand, we give in to the unconscious too much, it leads to a positive or negative inflation of the personality.

Without such care, a person is subject to psychological disaster, primarily the loss of the powers of discrimination:

An inflated consciousness is always egocentric and conscious of nothing but its own existence. It is incapable of learning from the past, incapable of understanding contemporary events, and incapable of drawing right conclusions about the future. It is hypnotized by itself and therefore cannot be argued with. It inevitably dooms itself to calamities that must strike it dead. Paradoxically enough, inflation is a regression of consciousness into

unconsciousness. This always happens when consciousness takes too many unconscious contents upon itself and loses the faculty of discrimination, the sine qua non of all consciousness.…It seems to me of some importance, therefore, that a few individuals, or people individually, should begin to understand that there are contents which do not belong to the ego-personality, but must be ascribed to a psychic non-ego. This mental operation has to be undertaken if we want to avoid a threatening inflation.

Jung’s view is that certain contents, although associated with the ego merely by the fact of being in the collective unconscious, are definitely non-ego and must be left so. Otherwise, one is swallowed up and destroyed by them:

…they are meant to fulfill their earthly existence with conviction and not allow themselves any spiritual inflation, otherwise they will end up in the belly of the spider. In other words, they should not set the ego in the highest place and make it the ultimate authority, but should ever be mindful of the fact that it is not sole master in its own house and is surrounded on all sides by the factor we call the unconscious. One can approach only with caution:b

The victory over the collective psyche alone yields the true value, the capture of the hoard, the invincible weapon, the magic talisman, or whatever it be that the myth deems most desirable. Therefore, whoever identifies with the collective psyche—or, in terms of the myth, lets himself be devoured by the monster—and vanishes in it, is near to the treasure that the dragon guards, but he is there by extreme constraint and to his own greatest harm.

From this, it can be seen that there is no question that, for Jung, identification with the ultimate deity would be a horrendous mistake. In his introduction to the Tibetan Book of the Dead he suggests that it is only Westerners who would take literally an injunction to identify with the clear light:

The soul is assuredly not small, but the radiant Godhead itself. The West finds this statement either very dangerous, if not downright blasphemous, or else accepts it unthinkingly and then suffers from a theosophical inflation. Somehow we always have a wrong attitude to these things. But if we can master ourselves far enough to refrain from our chief error of always wanting to do something with things and put them to practical use, we may perhaps succeed in learning an important lesson from these teachings, or at least in appreciating the greatness of the Bardo Thödol, which vouchsafes to the dead man the ultimate and highest truth, that even the gods are the radiance and reflection of our own souls.

It is clear from the presentations of Action yoga given above that, contrary to Jung’s warnings, the injunctions for identification are to be taken literally, to be implemented in practice. For Jung, this would be all the worse unless there were a means for mitigating the problems, which are by no means little:b According to the teachings of the Bardo Thödol, it is still possible for him, in each of the Bardo states, to reach the Dharmakāya by transcending the four-faced Mount Meru, provided that he does not yield to his desire to follow the “dim lights.” This is as much as to say that the individual must desperately

resist the dictates of reason, as we understand it, and give up the supremacy of egohood, regarded by reason as sacrosanct. What this means in practice is complete capitulation to the objective powers of the psyche, with all that this entails; a kind of figurative death, corresponding to the Judgment of the Dead in the Sidpa Bardo. It means the end of all conscious, rational, morally responsible conduct of life, and voluntary surrender to what the Bardo Thödol calls “karmic illusion.” Karmic illusion springs from belief in a visionary world of an extremely irrational nature, which neither accords with nor derives from our

rational judgments but is the exclusive product of uninhibited imagination. It is sheer dream or “fantasy,” and every well-meaning person will instantly caution us against it; nor indeed can one see at first sight what is the difference between the fantasies of this kind and phantasmagoria of a lunatic. The problems with identification—loss of essential rationality and perspective—are so great that even the alchemical model of a successful union, in which Jung

invested much interest, is for him only suggestive, far from the truth. Although on the one hand he says,a “…the alchemist’s endeavour to unite the corpus mundum, the purified body, with the soul is also the endeavour of the psychologist once he has succeeded in freeing the ego-conscious from contamination with the unconscious,” he also holds that the aim of such grand transmutation of the collective unconscious is partly an illusion:b

I hold the view that the alchemist’s hope of conjuring out of matter the philosophical gold, or the panacea, or the wonderful stone, was only in part an illusion, an effect of projection; for the rest it corresponded to certain psychic facts that are of great importance in the psychology of the unconscious. As is shown by the texts and their symbolism, the alchemist projected what I have called the process of individuation into the phenomena of chemical change.

Autonomous complexes. The theoretical underpinning of Jung’s caution is his estimation, based on experience both with his own quest and with patients, that complexes are autonomous:

This points also to the complex and its association material having a remarkable independence in the hierarchy of the psyche, so that one may compare the complex to revolting vassals in an empire.

Though autonomous complexes may and, in fact, must be approached, they never come under conscious control:d What then, scientifically speaking, is a “feeling-toned

complex”? It is the image of a certain psychic situation which is strongly accentuated emotionally and is, moreover, incompatible with the habitual attitude of consciousness. This image has a powerful inner coherence, it has its own wholeness and, in addition, a relatively high degree of autonomy, so that it is subject to the control of conscious mind to only a limited extent, and therefore behaves like an animated foreign body in the sphere of consciousness. The complex can usually be suppressed with an effort of will, but not argued out of existence, and at the first suitable opportunity it reappears in all its original strength.

Autonomous complexes seem even to have their own consciousness:

We have to thank the French psychopathologists, Pierre Janet in particular, for our knowledge today of the extreme dissociability of consciousness.…These fragments subsist relatively independently of one another and can take another’s place at any time, which means that each fragment possesses a high degree of autonomy.…whether such small psychic fragments as complexes are also capable of a consciousness of their own is a still unanswered question. I must confess that this question has often occupied my thoughts, for complexes behave like Descartes’ devils and seem to delight in playing impish tricks.…As one might expect on theoretical grounds, these impish complexes are unteachable.

They have the character of splinter psyches:

But even the soberest formulation of the phenomenology of complexes cannot get round the impressive fact of their autonomy, and the deeper one penetrates into their nature—I might almost say into their biology—the more clearly do they reveal their character as splinter psyches. And:

I have frequently observed that the typical traumatic affect

is represented in dreams as a wild and dangerous animal—a striking illustration of its autonomous nature when split off from consciousness. Furthermore, since autonomous complexes are the very structure of even normal psychic life, they remain autonomous and cannot be fully assimilated:a I am inclined to think that autonomous complexes are among the normal phenomena of life and that they make up the structure of the unconscious psyche. For Jung, it seems that almost everything is an autonomous complex. The soul is an autonomous complex:b Looked at historically, the soul, that many-faceted and much-interpreted concept, refers to a psychological content that must possess a certain measure of autonomy within the limits of consciousness. If this were not so, man would never have hit on the idea of attributing an independent existence to the soul, as though it were some objectively perceptible thing. It must be a content in which spontaneity is inherent, and hence also partial unconsciousness, as with every autonomous complex.

Objects of an ordinary consciousness are autonomous complexes, overvalued with psychic force, and religion seeks to collect back the libido that has been over-invested in the external:

To be like a child means to possess a treasury of accumulated libido which can constantly stream forth. The libido of the child flows into things; in this way he gains the world, then by degrees loses himself in the world (to use the language of religion) through a gradual over-valuation of things. The growing dependence on things entails the necessity of sacrifice, that is, withdrawal of libido, the severance of ties. The intuitive teachings of religion seek by this means to gather the energy together again; indeed, religion portrays this process of re-collection in its symbols.

Even when this overvaluation is withdrawn, God (or let us substitute the mind of clear light or ultimate deity) becomes an autonomous complex: If the ‘soul’ is a personification of unconscious contents, then, according to our previous definition, God too is an unconscious content, a personification in so far as he is thought of as personal, and an image of expression of something in so far as he is thought of as dynamic. God and the soul are essentially the

same when regarded as personifications of an unconscious content. Meister Eckhart’s view, therefore, is purely psychological. So long as the soul, he says, is not only in God, she is not blissful. If by “blissful” one understands a state of intense vitality, it follows from the passage quoted earlier that this state does not exist so long as the dynamic principle “God,” the libido, is projected upon objects. For, so long as God, the highest value, is not in the soul, it is somewhere outside. God must be withdrawn from objects and brought into the soul, and this is a “higher state” in which God himself is “blissful.”

Psychologically, this means that when the libido invested in God, that is, the surplus value that has been projected, is recognized as a projection, the object loses its overpowering significance, and the surplus value consequently accrues to the individual, giving rise to a feeling of intense vitality, a new potential. God, life at its most intense, then resides in the soul, in the unconscious. But this does not mean that God has become completely unconscious in the sense that all idea of him vanishes from consciousness. It is as though the supreme value were shifted elsewhere, so that it is now found inside and not

outside. Objects are no longer autonomous factors, but God has become an autonomous psychic complex. An autonomous complex, however, is always only partially conscious, since it is associated with the ego only in limited degree, and never to such an extent that the ego could wholly comprehend it, in which case it would no longer be autonomous.

Even the ego, the mediator, is an autonomous complex:b

Researches have shown that this independence is based upon an intense emotional tone, that is upon the value of the affective elements of the complex, because the ‘affect’ occupies in the constitution of the psyche a very independent place, and may easily break through the self-control and self-intention of the individual.…For this property of the complex I have introduced the term autonomy. I conceive the complex to be a collection of imaginings, which, in

consequence of this autonomy, is relatively independent of the central control of the consciousness, and at any moment liable to bend or cross the intentions of the individual. In so far as the meaning of the ego is psychologically nothing but a complex of imaginings held together and fixed by the coenesthetic impressions, also since its intentions or innervations are eo ipso stronger than those of the secondary complex (for they are disturbed by them), the complex of the ego may well be set parallel with and compared to the secondary autonomous complex.

Remarks

As we have seen, Jung’s estimation of the nature of the mind does not allow for complete transformation; it is of the nature of the mind for elements to remain unconsciously imbedded in its framework, assimilatable into consciousness only in the sense of the ego’s confronting them and then only in a never-ending, piecemeal way. We can speculate that, for him, identification with an ideal being—a deity—would exalt to the grandiose level of a systematic religious practice

the self-inculcation of inflation and all its attendant ills. Having lost respect for and a critical attitude toward unconscious contents and their powerful influence on mental life, one would have pretentiously assimilated too much to the ego in “positive inflation,” and also, due to denying the powerful autonomous contents that can wreak havoc with those who neglect them, one would eventually be overpowered by those autonomous contents— drowned in the larger self in “negative inflation.”

The ideal being as whom the practitioner would be masquerading would be unable to negotiate between the needs of unconscious contents to manifest and the imperative of effective individuation, drowned in a sea of a pretension of grand, merely public affectations of compassion, love, generosity, and so forth. Self-hypnotized, closed to criticism, bloated from feeling that the very structure of pure reality is his or her own basic nature, the practitioner would lose

the faculty of discrimination, the essence of a healthy psychological life. The basic problem would be the failure to recognize that since the structure of the psyche is to be found in autonomous complexes—ranging from unconscious contents in the personal unconscious, to those in the collective unconscious, to the ego itself—the primary need is to learn that these autonomous factors need to be negotiated; nothing could be worse than a pretension of grandiose control.

Possible amelioration of autonomous complexes in deity yoga

Jung’s cautions are based on considerable therapeutic experience, and it should be clear that I not only do not take them lightly but am considerably impressed with his insights. Still, several provocative questions can be raised in light of the description of deity yoga in Action Tantra:

1. The use of rationality in the initial step, the ultimate deity, to penetrate the appearance of objects as if they inherently exist or exist under their power suggests that recognition and realization of emptiness, even in a nondual manner, is not a surrender to irrationality but to be done only by a highly discriminative mind. It is likely that emptiness yoga—which is aimed at overcoming the sense that phenomena, mental and otherwise, exist under their own power, autonomously—could deautonomize complexes.

2. Much as Jung emphasizes not just the appearance of feelingtoned complexes to the conscious mind but also the conscious mind’s adopting a posture of confrontation, the Buddhist division of the mind of deity yoga into an appearance factor appearing as an ideal being and an ascertainment factor realizing emptiness suggests how discrimination is maintained in the face of a profoundly different type of appearance—in this case an ideal being—despite identification with that appearance. Identification has assumed a different meaning, for the meditator merely is identifying himself or herself as that pure person designated in dependence upon purely appearing mind and body and not findable either among or separate from mind and body.

3. Admittedly, the assumption of ultimate pride—the recognition that the deity’s final nature and one’s own are the same—may be a compensation for the negative inflation of being overly absorbed in emptiness and thus may be an expression of positive inflation. However, it is likely that identifying that one’s final nature is an absence of inherent, or autonomous, existence and that this emptiness is compatible with dependently arisen appearances counteracts positive inflation. Also, even though the final nature of a person is his or her emptiness of inherent existence, a person is not his or her emptiness of inherent existence. Similarly, even though the fundamental innate mind of clear light taught in Highest Yoga Mantra is the final basis of designation of a person, since a person is not his or her basis of designation, a person is not his or her fundamental innate mind of clear light. Furthermore, the fundamental innate mind of clear light is individual to each person. Hence, the meditation is neither that one is ultimate reality in general or the fundamental innate mind of clear light in general.

4. Just as Jung emphasizes the virtues of attention, conscientiousness, and patience as countermeasures to negative inflation— identified as too great absorption in the deeper self—so the compassionately active emanations at the point of the form deity in Action Tantra meditation establish altruism as the basic motivation and inner structure of individuation, re-appearance in ideally compassionate form, thereby establishing this practice as highly moral. The practice of transmuting depraved and deprived contents under the guise of quasi-otherness and the continuous recognition of the emptiness of inherent existence may provide a means for “teaching” even what Jung calls “impish” complexes despite his claim of their unteachability.

5. Though I have found no doctrinal injunctions corresponding to Jung’s call for more than public virtues, specifically for a connection with one’s own earthy self, the biographies of masters emphasize personalized feelings and reactions. Also, I have observed in Tibetan monastic communities how the community serves to exert pressure on persons who have become too grandly public in their virtues—through teasing, mild derision, mimicry, and so forth. Still, the danger of retreating into a persona of fatuous, unfounded, “good character” while at the same time wreaking havoc on all those around oneself is great.

In conclusion, the transmutation sought through deity yoga involves a constellation of techniques:

(1) development of positive moral qualities,

(2) confrontation with neurotic contents and gradual education of them,

(3) identification with the sublime, and

(4) de-autonomizing objects and consciousnesses through realization of the status of phenomena and through taking emptiness and wisdom as the stuff of appearance. J

Jung’s cautions, nevertheless, need to be heeded; his insights make it clear that deity yoga, if it is possible, is no easy matter.

Given its built-in safeguards and moral tone, there is the suggestion that deity yoga could actually succeed in overcoming inflation, despite the enormity of the task. Still, anyone who made such a proclamation would, most likely, be reeking with the stink of inflation.

With a sense of humility in the face of the issue that we are considering, let us take a detailed look at other elements in the Action Tantra path in the next three chapters.

ence given the fragility of Tsong-kha-pa’s teaching remaining in the world, and (5) intense longing to rejoin his teacher.” See the brief account in Tenzin Gyatso and Jeffrey Hopkins,