Kammavaca

History and Production Techniques of the Kammavaca.

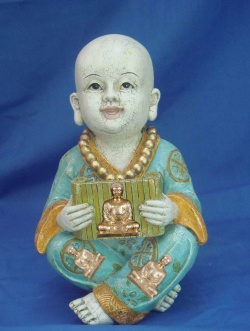

Kammavaca are among the most sacred of Burmese religious texts. Kammavaca (kammavaca in Pali) consist of nine Khandakas from the Pali Vinaya Pitaka, each of which relates to a specific ceremony associated with monks of the Theravada school of Buddhism.

Kammavaca were usually commissioned as works of merit to be presented to the Monk hood when a son entered the Buddhist Order as a novice or became ordained as a monk.

The earliest Kammavaca which date from the pagan period (1004-1287) were either incised with a stylus or written in ink or plain unadorned palm-leaf.

The beginnings of embellishment on Kammavaca appears to date from around the fourteenth century, with the discovery of a palm-leaf manuscript now with the Department of Archaeology, Rangoon, which was written in black ink on a gilt and red lacquer ground.

Around the latter half of the seventeenth century, a square type of writing executed in thick resinous black lacquered called ‘tamarind seed’ became the preferred script for Kammavaca.

Folded, heavily lacquered cloth became the preferred medium for the production of ‘pages’ for Kammavaca. The most highly prized were those made from waistcloths of kings or from the robes of highly revered monks.

Also at that time gold leaf (shwei-zawa) illustrations began to make their appearance in the margins and between the four to five lines of writing on a brown to reddish orange ground score with fine hatch strokes.

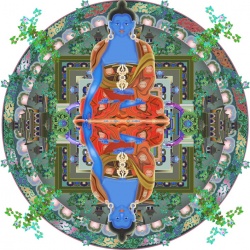

Margin embellishment gradually became more intricate in the following two centuries, and included bands of stylised lotus petals, monks’ fans , diamonds rhombs, beading, and large octagonal and circular rosette, mandala, and endless knot forms, as well as birds and snippets of foliage between the lines.

The Mon people of Lower Burma employed silver leaf rather than gold on their Kammavaca often using the round form rather than the square tamarind seed writing. Some Kammavaca in the eighteenth century were gilded with mo-gyo, an alloy of gold and silver.

Kammavaca reached their apogee during the Konbaung dynasty )1752-1885).

Five to seven lines of script became the norm and the background decoration of floral sprigs and birds between the lines became more intricate.

Covers and margin embellishment became more lavish featuring intricate linked geometric patterns, hintha birds the twenty-eight Buddha’s of previous world cycles and the present Buddha with disciples and praying Devas.

During the nineteenth century Kammavaca also came to be made from sheets of Ivory, brass and copper.

Production of Kammavaca continued unabated in the Amarapura-Mandalay area during the early part of the Twentieth century.

The more ‘modern’ Kammavaca consist of sixteen loose unbound ‘pages’, (the exact number varies depending on the length of the khandaka being inscribed).

Pages differ in size from 45cm to 65cm in length and from 10cm to 15cm in width.

They are made from four folded layers of cotton or chintz cloth thickly covered with a few Coats of orange and brown lacquer to create a smooth but plaint surface.

To prepare the ‘page’ for the text , the pages are first ruled up with a pen or brush in an orpiment solution to mark out the lines, margins, and appropriate spaces for embellishment. The script is then blocked out in orpiment. A

fter the gold-leaf is applied, an impression of the text shows through in the ground lacquer colour.

The words are then painted on with black lacquer which has been reduced by boiling to a thick gummy consistency.

After the text is written, the intervening lines are embellished in gold-leaf, using the negative technique.

Tiny delicate illustrations depicting snippets of foliage, birds, and small animals are set against a fine hatch stroke ground.

The margins surrounding the text are framed by a band of 2cm-wide gold scrolling in the form of curling tendrils often in the dha-zin-gwei design or in the upturned lotus petals motif.

Small circles and parallel and saw tooth lines finished the border patterns on all sides.

Pages are numbered according to the consonant and vowel sounds of the Burmese alphabet.

The pages of the kamawa-sa are protected by covers (kyan) of brown or orange lacquered teak wood. These are bevelled around the edges to give a slightly raised effect to the surface.

Like the pages they enclose, most covers are decorated with panels of lively free-hand gold- leaf (shwei-zawa) drawings from their Burmese fantasy world of the Deva, hi-tha, kinnara and to-naya.

Covers made of relief- molded lacquer inlaid with glass mosaic were also produced.

The most exquisite, however, are those of pierced Ivory which enclose extracts inscribed on pages of the same material. Unfortunately, the slightly greasy surface of the ivory can cause the lacquer to peel unless the manuscript is carefully stored in a heat and humidity- controlled atmosphere.

The title of the manuscript may sometimes be written in gilt on the inside cover.

The first and the last pages of a Kammavaca are not usually inscribed, but are illustrated with a series of panels echoing the mythical creatures which appear on the cover.

The text begins overleaf. The first and last pages of writing are inset with decorated panels on either side of the opening stanza.

This combination of script and illustrations creates the appearance of a medieval manuscript.

Kammavaca are read horizontally from left to right. Each page is turned away from the reader as it is finished and the next one begun.

Like all Burmese books, they are handled with great care. In former times Kammavaca were placed on a small stand when read. Women were expressly forbidden from placing pages in their laps.

After reading, the unbound pages were stacked and secured with bamboo pin passed through the two perforations on each page.

The book was carefully wrapped in a dust jacket (kabalwe) of silk, satin or velvet, sometimes reinforced with strips of bamboo.

Finally I was bound by a long ribbon (sa-si-gyo) woven on a card loom and placed in a gilded box for safe-keeping. The title might be inscribed on a sliver of bamboo or ivory and inserted within the bindings of the sa-si-gyo.