Difference between revisions of "Knowledge in Esoteric Khmer Buddhism"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:00x2400.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:00x2400.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | There are two kinds of [[knowledge]] {{Wiki|distinguished}} by the {{Wiki|Khmer}}: [[traditional]] [[knowledge]] and {{Wiki|modern}} [[knowledge]]. The Cambodian tradtion, and [[Theravada]] in general, placed high value on ‘received [[knowledge]]’ rather than ‘speculative [[knowledge]]’ and ‘innovative [[knowledge]]’ so highly valued by the {{Wiki|west}}. | + | There are two kinds of [[knowledge]] {{Wiki|distinguished}} by the {{Wiki|Khmer}}: [[traditional]] [[knowledge]] and {{Wiki|modern}} [[knowledge]]. The [[Cambodian]] tradtion, and [[Theravada]] in general, placed high value on ‘received [[knowledge]]’ rather than ‘speculative [[knowledge]]’ and ‘innovative [[knowledge]]’ so highly valued by the {{Wiki|west}}. |

| − | {{Wiki|Khmer}} [[tradition]] valued “[[knowing]] by [[heart]]” that emphasized memorization of text, [[meditation]] on the letters of the text. The texts were recited by [[heart]] by [[monks]], and this is still a highly emphasized practice throughout Cambodian communities today. {{Wiki|Traditionalists}} are critical of [[monks]] who cannot perform this service. The [[traditional]] practice of morning and evening [[chanting]] in {{Wiki|honor}} of the [[Triple Gem]], the Patimokh, are strictly observed. [Texts and [[prayers]] of such [[chants]] include: Kirimeanon, [[Girimananda]]; Eiseikili, [[Isigili]]; Mohasamay, Mahasamaya; Prumacak, Brahamacakka; Thoammacakka, [[Dhammacakka]].] | + | {{Wiki|Khmer}} [[tradition]] valued “[[knowing]] by [[heart]]” that emphasized [[memorization]] of text, [[meditation]] on the letters of the text. The texts were recited by [[heart]] by [[monks]], and this is still a highly emphasized practice throughout [[Cambodian]] communities today. {{Wiki|Traditionalists}} are critical of [[monks]] who cannot perform this service. The [[traditional]] practice of morning and evening [[chanting]] in {{Wiki|honor}} of the [[Triple Gem]], the Patimokh, are strictly observed. [Texts and [[prayers]] of such [[chants]] include: Kirimeanon, [[Girimananda]]; Eiseikili, [[Isigili]]; Mohasamay, Mahasamaya; Prumacak, Brahamacakka; Thoammacakka, [[Dhammacakka]].] |

What does it mean “to know” the text? | What does it mean “to know” the text? | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

The French-inspired modernists emphasized [[rationalist]], scriputralist, demythologized [[Buddhism]]. They deemphasized [[cosmological]] texts, particularly of the [[jatakas]] {{Wiki|past}} [[lives]] of the [[Buddha]]. | The French-inspired modernists emphasized [[rationalist]], scriputralist, demythologized [[Buddhism]]. They deemphasized [[cosmological]] texts, particularly of the [[jatakas]] {{Wiki|past}} [[lives]] of the [[Buddha]]. | ||

| − | The modernist reformers, following {{Wiki|French}} [[scholarly]] [[traditions]], reacted against the pedagogical [[tradition]] of rote memorization and {{Wiki|recitation}} of texts, instead {{Wiki|emphasizing}} the translation and interpretation of texts and sermons, between [[Pali]] and the {{Wiki|vernacular}}, so that both [[monks]] and [[lay people]] not only took part in the performance of texts, but more importantly, understood the content of what was {{Wiki|being}} read, {{Wiki|preached}} and recited. | + | The modernist reformers, following {{Wiki|French}} [[scholarly]] [[traditions]], reacted against the pedagogical [[tradition]] of rote [[memorization]] and {{Wiki|recitation}} of texts, instead {{Wiki|emphasizing}} the translation and interpretation of texts and [[sermons]], between [[Pali]] and the {{Wiki|vernacular}}, so that both [[monks]] and [[lay people]] not only took part in the performance of texts, but more importantly, understood the content of what was {{Wiki|being}} read, {{Wiki|preached}} and recited. |

The new {{Wiki|emphasis}} on [[scriptural]] [[Pali]] texts and [[monastic]] {{Wiki|behavior}}, instead of the [[traditional]] {{Wiki|emphasis}} on [[meditation]] practice and [[mystical]] [[attainment]], provoked {{Wiki|reaction}} from the “{{Wiki|traditionalists}}” because it undermined the old values of the “{{Wiki|folk}},” the “[[people]],” putting {{Wiki|emphasis}} on formal [[monks]]. | The new {{Wiki|emphasis}} on [[scriptural]] [[Pali]] texts and [[monastic]] {{Wiki|behavior}}, instead of the [[traditional]] {{Wiki|emphasis}} on [[meditation]] practice and [[mystical]] [[attainment]], provoked {{Wiki|reaction}} from the “{{Wiki|traditionalists}}” because it undermined the old values of the “{{Wiki|folk}},” the “[[people]],” putting {{Wiki|emphasis}} on formal [[monks]]. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

It undermined the notions of sanctity associated with the older palm-leaf {{Wiki|manuscript}} [[traditions]] that featured [[jatakas]] and [[abhidhamma]], and [[yantra]] ([[tantra]]). | It undermined the notions of sanctity associated with the older palm-leaf {{Wiki|manuscript}} [[traditions]] that featured [[jatakas]] and [[abhidhamma]], and [[yantra]] ([[tantra]]). | ||

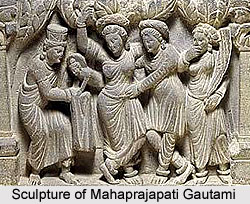

[[File:Mahaprajapati Gautami.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Mahaprajapati Gautami.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The old [[traditional]] [[forms]] of [[knowledge]] were based on {{Wiki|Khmer}} [[language]], the very script of which is [[sacred]] in itself to the {{Wiki|Khmer}} [[tradition]], allowing [[knowledge]] to [[plant]] [[seeds]] within the heart/mind, sprout, and grow. | + | The old [[traditional]] [[forms]] of [[knowledge]] were based on {{Wiki|Khmer}} [[language]], the very [[script]] of which is [[sacred]] in itself to the {{Wiki|Khmer}} [[tradition]], allowing [[knowledge]] to [[plant]] [[seeds]] within the heart/mind, sprout, and grow. |

The {{Wiki|French}} introduced textual [[criticism]] and {{Wiki|scholarship}}, and advocated a sort of “[[pure]]” “original” [[Buddhism]], as found in the [[Pali]] Text, promulgated by the {{Wiki|Pali Text Society}} based in Sir [[Lanka]]. This {{Wiki|movement}} created the [[impression]] of “uncovering a [[pure]]” [[Buddhism]]; and that het popular contemporary [[Buddhism]] that the [[people]] found around them was “corrupted, decayed,” and therefore needed to be reformed. The modernist reformers of {{Wiki|elite}}, [[scholarly]] [[Buddhism]] ensued. | The {{Wiki|French}} introduced textual [[criticism]] and {{Wiki|scholarship}}, and advocated a sort of “[[pure]]” “original” [[Buddhism]], as found in the [[Pali]] Text, promulgated by the {{Wiki|Pali Text Society}} based in Sir [[Lanka]]. This {{Wiki|movement}} created the [[impression]] of “uncovering a [[pure]]” [[Buddhism]]; and that het popular contemporary [[Buddhism]] that the [[people]] found around them was “corrupted, decayed,” and therefore needed to be reformed. The modernist reformers of {{Wiki|elite}}, [[scholarly]] [[Buddhism]] ensued. | ||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

[[File:Many Buddha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Many Buddha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

[[Traditional]] Text [[Traditions]] | [[Traditional]] Text [[Traditions]] | ||

| − | “{{Wiki|Khmer}} texts were [[traditionally]] preserved either in palm-leaf manuscripts or accordion-style folded paper manuscripts inscribed with ink or chalk. Since few opportunities for [[education]] existed outside the [[monastery]], {{Wiki|literary}} and [[writing]] were closely linked to [[religious]] practice. [[Writing]] in itself was highly valued and [[spiritually]] potent. Manuscripts were produced with great care, surrounded by [[rituals]] for preparing the palm leaves and {{Wiki|ceremonies}} and regulations that had to be observed by [[monks]] who inscribed them. Finished manuscripts were [[consecrated]], and the presentation of a manuscripts to a [[monastery]] required a [[ritual]] {{Wiki|ceremony}}, such as the presentation of spread cloth for wrapping the texts or the donation of [[robes]] to the monk-scribe in [[order]] to effect the passing of [[merit]] to the {{Wiki|donor}} of the {{Wiki|manuscript}}. The quality and efficiency of the {{Wiki|manuscript}} depended in part on the [[beauty]] of its written words, which in turn reflected the [[mindfulness]] of the [[monk]] who inscribed it, since in many cases, written {{Wiki|syllables}} of the teachings were considered as microcosmic {{Wiki|representations}} of [[Buddha]]. The production of the {{Wiki|manuscript}} was thus an act of [[devotion]] whose quality could be judged according to its clarity, lack of [[writing]] errors, and {{Wiki|aesthetic}} [[character]]. Imbued with these [[elements]] of the [[Buddha]] and the [[Dhamma]], of [[merit]] and [[devotion]] manuscripts were venerated as aural texts, meant to be [[heard]], conferring [[merit]] on their listeners and on the [[monks]] who read or chanted them, and as written texts, venerated in and of themselves for their written [[nature]]. Ideologically committed to new technologies of textual translation and print dissemination, modernists rejected these [[traditional]] methods associated with {{Wiki|manuscript}} production as well as other older practices, [[ritual]] conventions, and ways of transmitting [[knowledge]] connected with the {{Wiki|manuscript}} {{Wiki|culture}} of {{Wiki|learning}}.” [Hansen, How to Behave.] | + | “{{Wiki|Khmer}} texts were [[traditionally]] preserved either in palm-leaf manuscripts or accordion-style folded paper manuscripts inscribed with ink or chalk. Since few opportunities for [[education]] existed outside the [[monastery]], {{Wiki|literary}} and [[writing]] were closely linked to [[religious]] practice. [[Writing]] in itself was highly valued and [[spiritually]] potent. Manuscripts were produced with great care, surrounded by [[rituals]] for preparing the palm leaves and {{Wiki|ceremonies}} and regulations that had to be observed by [[monks]] who inscribed them. Finished manuscripts were [[consecrated]], and the presentation of a manuscripts to a [[monastery]] required a [[ritual]] {{Wiki|ceremony}}, such as the presentation of spread cloth for wrapping the texts or the donation of [[robes]] to the monk-scribe in [[order]] to effect the passing of [[merit]] to the {{Wiki|donor}} of the {{Wiki|manuscript}}. The quality and efficiency of the {{Wiki|manuscript}} depended in part on the [[beauty]] of its written words, which in turn reflected the [[mindfulness]] of the [[monk]] who inscribed it, since in many cases, written {{Wiki|syllables}} of the teachings were considered as [[microcosmic]] {{Wiki|representations}} of [[Buddha]]. The production of the {{Wiki|manuscript}} was thus an act of [[devotion]] whose quality could be judged according to its clarity, lack of [[writing]] errors, and {{Wiki|aesthetic}} [[character]]. Imbued with these [[elements]] of the [[Buddha]] and the [[Dhamma]], of [[merit]] and [[devotion]] manuscripts were venerated as aural texts, meant to be [[heard]], conferring [[merit]] on their [[listeners]] and on the [[monks]] who read or chanted them, and as written texts, venerated in and of themselves for their written [[nature]]. Ideologically committed to new technologies of textual translation and print dissemination, modernists rejected these [[traditional]] methods associated with {{Wiki|manuscript}} production as well as other older practices, [[ritual]] conventions, and ways of transmitting [[knowledge]] connected with the {{Wiki|manuscript}} {{Wiki|culture}} of {{Wiki|learning}}.” [Hansen, How to Behave.] |

Hansen describes the texts as a sort of talisman. “{{Wiki|Khmer}} families, {{Wiki|individuals}}, and [[monks]] who owned texts viewed them as [[sacred]] [[objects]] to be used and maintained for [[ritual]] and most important was that, in their [[minds]], texts presented to [[temples]] were meant to generate [[merit]]: to remove texts donated for this [[purpose]] was [[unthinkable]].” | Hansen describes the texts as a sort of talisman. “{{Wiki|Khmer}} families, {{Wiki|individuals}}, and [[monks]] who owned texts viewed them as [[sacred]] [[objects]] to be used and maintained for [[ritual]] and most important was that, in their [[minds]], texts presented to [[temples]] were meant to generate [[merit]]: to remove texts donated for this [[purpose]] was [[unthinkable]].” | ||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

“A [[monastery]], like the {{Wiki|kingdom}}, was better off – stronger and purer – if it possessed texts. A prevailing [[view]] of texts was of {{Wiki|physically}} potent [[objects]] that affected the [[spiritual]] wellbeing of the {{Wiki|individuals}} who handled them; their exact contents were of [[lesser]] importance. Texts were understood to be [[sacred]] in much the same way as [[relics]], which embody [[physical]] [[elements]] of the [[Buddha]]. {{Wiki|Being}} in [[physical]] proximity or [[contact]] with texts, {{Wiki|touching}} them, [[seeing]] them, or [[hearing]] them, connected one with the [[Buddha]] and his [[teaching]] devotionally. These acts generated [[merit]] first, and led to [[greater]] intellectualized [[forms]] of [[understanding]] only as a secondary [[aim]], if at all; rather, devotional acts generated a different kind of [[insight]], more akin to [[meditational]] [[understanding]]…” | “A [[monastery]], like the {{Wiki|kingdom}}, was better off – stronger and purer – if it possessed texts. A prevailing [[view]] of texts was of {{Wiki|physically}} potent [[objects]] that affected the [[spiritual]] wellbeing of the {{Wiki|individuals}} who handled them; their exact contents were of [[lesser]] importance. Texts were understood to be [[sacred]] in much the same way as [[relics]], which embody [[physical]] [[elements]] of the [[Buddha]]. {{Wiki|Being}} in [[physical]] proximity or [[contact]] with texts, {{Wiki|touching}} them, [[seeing]] them, or [[hearing]] them, connected one with the [[Buddha]] and his [[teaching]] devotionally. These acts generated [[merit]] first, and led to [[greater]] intellectualized [[forms]] of [[understanding]] only as a secondary [[aim]], if at all; rather, devotional acts generated a different kind of [[insight]], more akin to [[meditational]] [[understanding]]…” | ||

[[File:MahapajapatiGotami.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:MahapajapatiGotami.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Penny Edwards said:”Due to their long-standing use as the {{Wiki|tangible}} vehicles of [[Buddhist teachings]] or [[dhamma]], palm-leaf manuscripts became [[objects]] of [[sacred]] [[power]] in their own right in the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|societies}} of {{Wiki|Southeast Asia}}.” | + | Penny Edwards said:”Due to their long-standing use as the {{Wiki|tangible}} vehicles of [[Buddhist teachings]] or [[dhamma]], palm-leaf manuscripts became [[objects]] of [[sacred]] [[power]] in their [[own]] right in the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|societies}} of {{Wiki|Southeast Asia}}.” |

“The [[preparation]], [[transfer]], and maintenance of [[Buddhist]] manuscripts involved acts of [[consecration]], [[dedication]], and presentation centering on the notion of the manuscripts intrinsic and [[accumulated]] [[merit]].” | “The [[preparation]], [[transfer]], and maintenance of [[Buddhist]] manuscripts involved acts of [[consecration]], [[dedication]], and presentation centering on the notion of the manuscripts intrinsic and [[accumulated]] [[merit]].” | ||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

“The texts underpinning the [[tradition]] are often obscure, are clearly [[symbolic]], and may be subjected to multiple interpretations. They have much to say about [[ritual]] and frequently contain [[mantras]] in [[Pali]]. The [[tradition]] is clearly old and certainly predates the reform movements of the nineteenth century.” | “The texts underpinning the [[tradition]] are often obscure, are clearly [[symbolic]], and may be subjected to multiple interpretations. They have much to say about [[ritual]] and frequently contain [[mantras]] in [[Pali]]. The [[tradition]] is clearly old and certainly predates the reform movements of the nineteenth century.” | ||

| − | The Saddhavimala was in important Cambodian text studied by Bizot and Laguarde, a text which relates that the seven [[books]] of the [[Abhidhamma]] are the creative force behind the [[body]] and [[mind]] of all things. The oral {{Wiki|recitation}} of the [[Abhidhamma]] is very {{Wiki|powerful}}, particularly the Mahapatthana, the final work. Each of the seven [[books]] is connected with a day of the week and a part of the [[body]]. | + | The Saddhavimala was in important [[Cambodian]] text studied by Bizot and Laguarde, a text which relates that the seven [[books]] of the [[Abhidhamma]] are the creative force behind the [[body]] and [[mind]] of all things. The oral {{Wiki|recitation}} of the [[Abhidhamma]] is very {{Wiki|powerful}}, particularly the Mahapatthana, the final work. Each of the seven [[books]] is connected with a day of the week and a part of the [[body]]. |

[[File:Ima789ges.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Ima789ges.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Mahadibbamanta, an undated Pali-language palm leaf [[paritta]] text, inscribed in {{Wiki|Khmer}} characters and probably of Cambodian origin, housed in the National Museum of {{Wiki|Bangkok}}. The text represents [[tantric]] [[esotericism]] in [[Theravada]] [[tradition]]. “It consists of [[108]] verses, an [[auspicious]] number also mentioned in the work itself. One of the unusual {{Wiki|features}} of the text is that it describes a [[mandala]] of the eight chief [[disciples]] of the [[Buddha]]. It also includes a [[mantra]] hulu, hulu, hulu sva ha and some verses of benediction ([[siddhi]] [[gatha]]) which glorify a range of [[deities]], including the earth-goddess, the [[Buddha]], [[Hara]], Hirihara, and {{Wiki|Rama}} and the [[nagas]]. The Mahadibbamanta manta equates the [[Buddha]] with various major and minor [[divinities]] and concludes with an assurance of the [[magical]] efficiency of the texts {{Wiki|recitation}}, particularly in countering enemies…the work is not uncharacteristic of the [[Pali]] [[Theravada]] {{Wiki|literature}} that had circulated in [[Cambodia]] for several centuries.” [Harris.] | + | Mahadibbamanta, an undated Pali-language palm leaf [[paritta]] text, inscribed in {{Wiki|Khmer}} characters and probably of [[Cambodian]] origin, housed in the National Museum of {{Wiki|Bangkok}}. The text represents [[tantric]] [[esotericism]] in [[Theravada]] [[tradition]]. “It consists of [[108]] verses, an [[auspicious]] number also mentioned in the work itself. One of the unusual {{Wiki|features}} of the text is that it describes a [[mandala]] of the eight chief [[disciples]] of the [[Buddha]]. It also includes a [[mantra]] hulu, hulu, hulu [[sva]] ha and some verses of benediction ([[siddhi]] [[gatha]]) which glorify a range of [[deities]], including the earth-goddess, the [[Buddha]], [[Hara]], Hirihara, and {{Wiki|Rama}} and the [[nagas]]. The Mahadibbamanta manta equates the [[Buddha]] with various major and minor [[divinities]] and concludes with an assurance of the [[magical]] efficiency of the texts {{Wiki|recitation}}, particularly in countering enemies…the work is not uncharacteristic of the [[Pali]] [[Theravada]] {{Wiki|literature}} that had circulated in [[Cambodia]] for several centuries.” [Harris.] |

The major [[traditional]] [[cosmological]] texts in [[Cambodia]] are the familiar [[root]] texts of the boran ({{Wiki|ancient}} practice): | The major [[traditional]] [[cosmological]] texts in [[Cambodia]] are the familiar [[root]] texts of the boran ({{Wiki|ancient}} practice): | ||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

· Traiwet. | · Traiwet. | ||

| − | “The arrival of the {{Wiki|French}} and [[gradual]] imposition of the [[conditions]] of modernity on the [[Buddhist]] [[sangha]] had a profound impact on all aspects of Cambodian {{Wiki|culture}}, particularly in the field of [[writing]]. [[Traditional]] {{Wiki|literary}} [[activity]] was one of the immediate casualties, as [[monks]] turned away from the laborious and [[ritually]] circumscribed techniques associated with [[traditional]] {{Wiki|manuscript}} production to adopt [[writing]] in European-style notebooks. In [[time]], many turned to [[printing]], and the old copyists craft with its merit-making underpinnings began a dramatic {{Wiki|decline}}. In addition, an {{Wiki|archaic}} and [[essentially]] [[magical]] [[vision]] of the [[universe]], in which inscribed {{Wiki|Khmer}} characters are assigned [[occult]] [[powers]], was largely undermined….It is rare today to find [[monks]] who have any [[confidence]] in reading [[traditional]] [[cosmological]] works, such as the Traiphum, which once formed the core of the {{Wiki|Khmer}} {{Wiki|literary}} cannon.” [Harris.] | + | “The arrival of the {{Wiki|French}} and [[gradual]] imposition of the [[conditions]] of modernity on the [[Buddhist]] [[sangha]] had a profound impact on all aspects of [[Cambodian]] {{Wiki|culture}}, particularly in the field of [[writing]]. [[Traditional]] {{Wiki|literary}} [[activity]] was one of the immediate casualties, as [[monks]] turned away from the laborious and [[ritually]] circumscribed techniques associated with [[traditional]] {{Wiki|manuscript}} production to adopt [[writing]] in European-style notebooks. In [[time]], many turned to [[printing]], and the old copyists craft with its merit-making underpinnings began a dramatic {{Wiki|decline}}. In addition, an {{Wiki|archaic}} and [[essentially]] [[magical]] [[vision]] of the [[universe]], in which inscribed {{Wiki|Khmer}} characters are assigned [[occult]] [[powers]], was largely undermined….It is rare today to find [[monks]] who have any [[confidence]] in reading [[traditional]] [[cosmological]] works, such as the Traiphum, which once formed the core of the {{Wiki|Khmer}} {{Wiki|literary}} cannon.” [Harris.] |

“The [[sacred]] [[physical]] and devotional aspects of textuality were in many respects diminished and altered with the transition to print {{Wiki|culture}} that occurred during the 1920s…” | “The [[sacred]] [[physical]] and devotional aspects of textuality were in many respects diminished and altered with the transition to print {{Wiki|culture}} that occurred during the 1920s…” | ||

Latest revision as of 08:21, 24 February 2015

There are two kinds of knowledge distinguished by the Khmer: traditional knowledge and modern knowledge. The Cambodian tradtion, and Theravada in general, placed high value on ‘received knowledge’ rather than ‘speculative knowledge’ and ‘innovative knowledge’ so highly valued by the west.

Khmer tradition valued “knowing by heart” that emphasized memorization of text, meditation on the letters of the text. The texts were recited by heart by monks, and this is still a highly emphasized practice throughout Cambodian communities today. Traditionalists are critical of monks who cannot perform this service. The traditional practice of morning and evening chanting in honor of the Triple Gem, the Patimokh, are strictly observed. [Texts and prayers of such chants include: Kirimeanon, Girimananda; Eiseikili, Isigili; Mohasamay, Mahasamaya; Prumacak, Brahamacakka; Thoammacakka, Dhammacakka.]

What does it mean “to know” the text?

In traditional Khmer Buddhism, special status was associated with primarily meditative prowess which was understood to endow the monk-adept with extraordinary powers or iddhi.

They did not especially value the scholarly, intellectual, speculative knowledge valued by the west, and modernist educational reforms imposed by the French.

The French-inspired modernists emphasized rationalist, scriputralist, demythologized Buddhism. They deemphasized cosmological texts, particularly of the jatakas past lives of the Buddha.

The modernist reformers, following French scholarly traditions, reacted against the pedagogical tradition of rote memorization and recitation of texts, instead emphasizing the translation and interpretation of texts and sermons, between Pali and the vernacular, so that both monks and lay people not only took part in the performance of texts, but more importantly, understood the content of what was being read, preached and recited.

The new emphasis on scriptural Pali texts and monastic behavior, instead of the traditional emphasis on meditation practice and mystical attainment, provoked reaction from the “traditionalists” because it undermined the old values of the “folk,” the “people,” putting emphasis on formal monks.

It undermined the notions of sanctity associated with the older palm-leaf manuscript traditions that featured jatakas and abhidhamma, and yantra (tantra).

The old traditional forms of knowledge were based on Khmer language, the very script of which is sacred in itself to the Khmer tradition, allowing knowledge to plant seeds within the heart/mind, sprout, and grow.

The French introduced textual criticism and scholarship, and advocated a sort of “pure” “original” Buddhism, as found in the Pali Text, promulgated by the Pali Text Society based in Sir Lanka. This movement created the impression of “uncovering a pure” Buddhism; and that het popular contemporary Buddhism that the people found around them was “corrupted, decayed,” and therefore needed to be reformed. The modernist reformers of elite, scholarly Buddhism ensued.

When Buddhist texts were translated from Pali into Khmer, the translators used the common language which stays closer to the ordinary speech, for the purposes of preaching. This indicates the populism of the Theravada movement in Cambodia; whereas the Buddhist reformers emphasized the “high” language for the purposes of scholarship or royalty.

Traditional Buddhism was interested in cosmography rather than psychology. They emphasized community rituals and practices for personal cultivation. The western-inspired modern reforms neglected the cosmological dimensions, and ritual aspects of Buddhism; and moved toward an emphasis on individual, rationality and morality.

The Theravada Buddhists of Cambodia attempted to accommodate modernism while preserving the essence of Buddhism. Their response to the pressure of modernity moved from the traditional interpretations to the modernist interpretations:

· Cosmology > psychology

· Community practice > individual practice

· Jataka stories > academic scholarship

· Merit making> meditation

· Superstition> reason

· Folk/populist>elite

· Vernacular>Pali

· Commentaries> suttas

Traditional Text Traditions

“Khmer texts were traditionally preserved either in palm-leaf manuscripts or accordion-style folded paper manuscripts inscribed with ink or chalk. Since few opportunities for education existed outside the monastery, literary and writing were closely linked to religious practice. Writing in itself was highly valued and spiritually potent. Manuscripts were produced with great care, surrounded by rituals for preparing the palm leaves and ceremonies and regulations that had to be observed by monks who inscribed them. Finished manuscripts were consecrated, and the presentation of a manuscripts to a monastery required a ritual ceremony, such as the presentation of spread cloth for wrapping the texts or the donation of robes to the monk-scribe in order to effect the passing of merit to the donor of the manuscript. The quality and efficiency of the manuscript depended in part on the beauty of its written words, which in turn reflected the mindfulness of the monk who inscribed it, since in many cases, written syllables of the teachings were considered as microcosmic representations of Buddha. The production of the manuscript was thus an act of devotion whose quality could be judged according to its clarity, lack of writing errors, and aesthetic character. Imbued with these elements of the Buddha and the Dhamma, of merit and devotion manuscripts were venerated as aural texts, meant to be heard, conferring merit on their listeners and on the monks who read or chanted them, and as written texts, venerated in and of themselves for their written nature. Ideologically committed to new technologies of textual translation and print dissemination, modernists rejected these traditional methods associated with manuscript production as well as other older practices, ritual conventions, and ways of transmitting knowledge connected with the manuscript culture of learning.” [Hansen, How to Behave.]

Hansen describes the texts as a sort of talisman. “Khmer families, individuals, and monks who owned texts viewed them as sacred objects to be used and maintained for ritual and most important was that, in their minds, texts presented to temples were meant to generate merit: to remove texts donated for this purpose was unthinkable.”

This is why monks concealed the texts from non-Buddhist French colonialists. And also explains why they resisted so strongly the book-print culture imposed by the French and modernist monks.

“A monastery, like the kingdom, was better off – stronger and purer – if it possessed texts. A prevailing view of texts was of physically potent objects that affected the spiritual wellbeing of the individuals who handled them; their exact contents were of lesser importance. Texts were understood to be sacred in much the same way as relics, which embody physical elements of the Buddha. Being in physical proximity or contact with texts, touching them, seeing them, or hearing them, connected one with the Buddha and his teaching devotionally. These acts generated merit first, and led to greater intellectualized forms of understanding only as a secondary aim, if at all; rather, devotional acts generated a different kind of insight, more akin to meditational understanding…”

Penny Edwards said:”Due to their long-standing use as the tangible vehicles of Buddhist teachings or dhamma, palm-leaf manuscripts became objects of sacred power in their own right in the Buddhist societies of Southeast Asia.”

“The preparation, transfer, and maintenance of Buddhist manuscripts involved acts of consecration, dedication, and presentation centering on the notion of the manuscripts intrinsic and accumulated merit.”

Writing in and of itself was highly valued and spiritually potent…surrounded by rituals preparing palm leaves, and ceremonies and rituals had to be observed by the monks who inscribed them.

Esoteric Texts:

Khmer Buddhist writings are ritualistic and experimental rather that doctrinal, theoretical, didactic. They are esoteric, apparently “unorthodox” Theravada. They were designed to be taught under an adept. Francois Bizot “has revealed the existence of non -orthodox Buddhist meditational practices that have been largely secret.”

“The texts underpinning the tradition are often obscure, are clearly symbolic, and may be subjected to multiple interpretations. They have much to say about ritual and frequently contain mantras in Pali. The tradition is clearly old and certainly predates the reform movements of the nineteenth century.”

The Saddhavimala was in important Cambodian text studied by Bizot and Laguarde, a text which relates that the seven books of the Abhidhamma are the creative force behind the body and mind of all things. The oral recitation of the Abhidhamma is very powerful, particularly the Mahapatthana, the final work. Each of the seven books is connected with a day of the week and a part of the body.

Mahadibbamanta, an undated Pali-language palm leaf paritta text, inscribed in Khmer characters and probably of Cambodian origin, housed in the National Museum of Bangkok. The text represents tantric esotericism in Theravada tradition. “It consists of 108 verses, an auspicious number also mentioned in the work itself. One of the unusual features of the text is that it describes a mandala of the eight chief disciples of the Buddha. It also includes a mantra hulu, hulu, hulu sva ha and some verses of benediction (siddhi gatha) which glorify a range of deities, including the earth-goddess, the Buddha, Hara, Hirihara, and Rama and the nagas. The Mahadibbamanta manta equates the Buddha with various major and minor divinities and concludes with an assurance of the magical efficiency of the texts recitation, particularly in countering enemies…the work is not uncharacteristic of the Pali Theravada literature that had circulated in Cambodia for several centuries.” [Harris.]

The major traditional cosmological texts in Cambodia are the familiar root texts of the boran (ancient practice):

· Traiphum – the “Tree Worlds”. The text is a version was published in Phnom Penh by Japanese Sotasha Relief Committee in 1996 with an introduction by Michel Tranet.

· Traiphet – a Khmer text dating with the origin of the world. It is a treatise dealing with Brahman legends

· Traiyuk – is the three world stages (1st, 3rd, 4th).

· Traita – is a treatise dealing with the second world stage

· Traiwet.

“The arrival of the French and gradual imposition of the conditions of modernity on the Buddhist sangha had a profound impact on all aspects of Cambodian culture, particularly in the field of writing. Traditional literary activity was one of the immediate casualties, as monks turned away from the laborious and ritually circumscribed techniques associated with traditional manuscript production to adopt writing in European-style notebooks. In time, many turned to printing, and the old copyists craft with its merit-making underpinnings began a dramatic decline. In addition, an archaic and essentially magical vision of the universe, in which inscribed Khmer characters are assigned occult powers, was largely undermined….It is rare today to find monks who have any confidence in reading traditional cosmological works, such as the Traiphum, which once formed the core of the Khmer literary cannon.” [Harris.]

“The sacred physical and devotional aspects of textuality were in many respects diminished and altered with the transition to print culture that occurred during the 1920s…”

During the modern reforms of the 20th century, the modern textual criticism made a distinction between the physical text, and the authentic potency of understanding the authoritative meaning of the text, to order the conduct of the monk. This provided “purification” if understanding and conduct.

By 1929, the struggle between printed books and inscribed palm leaf was resolved, and printed books became more accepted. The “modernist” group became more ascendant in the Khmer Sangha. The new monks “modern dharma” shifted away from production of texts for entertainment/celebration purpose, performance, devotion, merit making, toward edification, education, instruction for ethical conduct, understanding of Buddha’s teaching (right view), and was concerned with accessibility.

As the scholastic Buddhism gained ascendency, the esoteric traditions receded into the background in Cambodia.