Korea Yogacara

Tonino Puggioni*

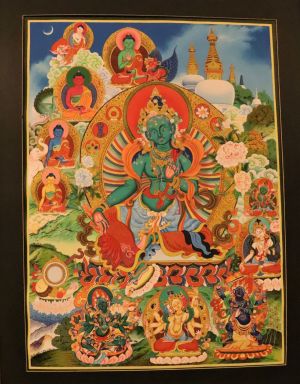

Many authorltatlve works have been published on the doctrines of the Yogacara school. It IS particularly striking, however, that almost nothing has been published on the faith practiced daily by the Yogacara and Faxiang mastersl or the religious images that were the object of their veneration. Generally speaking, we find that the monks of the Yogacara venerated, addition to the Budtha, the figures of Mmtreya, Amttabha, Ksitigarbha, Avalokltesvara, and Samantabhadra. Among these, the highest positions were occupied by Amitabha and Ksthgarbha. Due to the importance attached to meditation among the Yogacara Imsters, the

Researcher, Itahan Embassy, Singapore

1 The Yogacara school was started In India around the IV century AD by the monk Asanga. The school flourished thanks In part to the works of Asanga's younger brother Vasubandhu A long senes of scholarly monks, among whom Dignaga, Sthiramati, Paramartha, and others succeeded In making the school one of the most Important streams of Buddhist thought The Faxtang sect was founded In Tang China by Xuanzans disciple Kugt, but Its glory was short-hved, as It suffered a severe setback followig the persecutions of the Huzchang era (841-846) Its thought was transmitted to Korea, where It became one of the most Important scholastic schools until the end of the Goryeo penod, as well as to Japan, where It has been preserved In a few temples up to this day.

following inquiry commences With a section dedicated to this problem. Next follows a section on the pantheon of the sect, identifying the main figures of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas that were preferred by monks of the sect. Finally, the paper delves into the practical aspects of faith within the monastic commuruties belonging to this tradition. The subject admittedly requires more detailed research, so, for the present, this paper Just provides an outline of the problem, mainly limiting the area of concern to the Korean tradition

The Cultivation of the Way

The masters of the Yogacara school placed the utmost Importance on the practice of meditation, and this is perhaps the reason why the school came to be called "Yogacara." The school's objective was for practitioners to achieve Enlightenment after passmg through long and laborious meditation rituals and strictly observmg rigorous monastic rides called the "vznaya " No detailed descriptions exist on the manner the Yogacara adepts actually organized their daily activities, but they seem to have alternated periods of intense study With penods of long and deep meditation throughout the course of the day.

The Yogacara masters apparently inherited meditation practices as expounded in the meditation manuals of the Sarvastzvadm school's literary tradition, which had flourished In Kashmir around 100 A.D., though they are somewhat revised and gathered under the monumental

Yogacarabhunn-sastra,2 a work dating from around the nuddle of the 300

2 Paul Dennevllle "Le Chapltre de la Bodhisattvabhumz sur la Perfection du Dhyana d'Etudes Bouddhzques, 1929-1970 Inden Brill, 1973 pp 300-319 PUGGIONI The Yogacara-Fmang

A.D. and attributed to Asanga.

References to the type of meditation practiced by the Yogacara masters are abundant in the school's literary record. Through a careful textual analysis It is possible to detect changes meditational practices from one period to the next. For instance, at the outset we can observe strong Hinayanic Abhidharma influences, in the practices of the Five Ways and the Ftve Stages [pancayogabhumt; _ñ&þÐ], also known as the Ftve Posthons, EfiŽ].3 These gradually intertwine with the methods of the Ten Stages of the Bothzsattva which clearly have a Mahayamsttc flavor.

The theoretical basis of Yogacara meditation rests on the theory of the Three Natures, which the theories of the Five Stages and the Ten Stages of the Bodhisattva also rely on. We can say that the Immense literary corpus produced by the Yogacara school is an attempt to give an Interpretation of the mental and cognitive processes that take place in the course of meditation. At the same time, it lent their meditation techniques a solid theoretical basis.

The extreme importance attached to meditation In this case, which is not so different from other Buddhist schools, was grounded in the

3 The theory of the Fzve Stages had a long process of development It saw Its definite systematization thanks to the work of Dhannapala (530-561), one of the so-called Ten Great Commentators O, Hyeong-geun "Yuslk gyohak-eseou suhaeng-gwa geu Jeunggwa" •f',fi54 El Practice and Merit In the Mmd-Only Doctržnel Yuszk sasgng yeon-gu Studies In Mind-Only Thought] Seoul Gyeongseowon, 1983 pp 253-274

4 This doctrine was not given very much attention by the later commentators of the school m India, but It was at the basis of Vasubandzu's system of thought Stephan Anacker Seven Works of Vasubandhu, The Buddhist Psychological Doctor Delhi Motllal Banarsldass, 1984

belief that meditation provided a means to attain supreme knowledge and enlightenment As described in Chapter XIII of the Yogacarabhumi, it was believed that through meditation, traits such as eloquence and clarity of thought could be gamed, along with the ability to write commentaries and works of art, heal and nourish the needy, make rain fall during the dry season and attain the power to make miracles and exfraordmary feats that could be of benefit to others.

I)descripfions of the rœdltation process are given in the Smthimrmocanasutra, in the Yogacarabhumi-sastra, the Mahayana Lankavatara-sastm, the Abhisamayalamkara, the Mahayana-Sutralamkara, the Mahayanasamgraha (which IS attributed to Asanga), and the Madhyanta vibhaga-bhasya [the Rebirth Treatise] written by Vasubandhu 5 to Cite a few important texts.

The unequivocally Mahayamstzc doctrine of the Ten Stages of the Bodhisattva, as outlined in (chapter IX of the Samdhimrmocana-sutra and in the Dasabhubumika-sutra,6 occupies a central place in the Yogacara process of cultivation.

In line with the doctrmal principles of the school and Buddhism in general, meditation in its first stages is oriented towards forsaking the sensorial level of truth This is done through an analysis of the object, its constituents and characteristics, be it external or be it the self, of names and their contents, and their relinquishment through a thorough medltation practice based on the binary system of samatha and

5 Sukhavativyuhopadesa T 1524

6 The Dhasabhumika-sutra IS one of the two parts of which the

IS composed, the other being the Gmdmyuha-sutra The of the Budðzazoatmnsakasutra can be surnused from the fact that It comes first In the order of the canon of the Yogacara school The reason

for this could be that the ten stages of the Bodhisattva were an Integral part of the meditation process of the Yogacara practitioners

The Yogacara-Faxiang vipasyana.

A detailed description of the meditation process is contained in

chapter VIII of the Samdhinirmocana-sutra.7 In this chapter, where Maitreya takes the center stage, we find clearly stated objectives of meditation—that IS to say, the goals of supreme and pure and a precise description of the path to reach it.

First of all, the Bothisattva listens to the exposition of the Dharma, as contamed in the sacred scriptures in the form of episodes from the life of the Buddha, as well as quotations, tales, sermons in prose and poetry, instructions, and stories from the previous lives of the Buddha. After this, the Bodhisattva redirects his attention inwards and starts to reflect on the words of the Budddha and the content of the scriptures. From this ensues a state of physical and spiritual calmness called samatha. The Bodisattva dwells this state of calmness and, forsakmg all modes of thought, examines in detail the positive dharmas by way of images perceived through inner concentration. This kind of examination is called introspection, or vipasyana.

Calmness and introspection determine the rise of pure thought, pure wisdom and all positive dharmas, bringing two results: they free the Bothisattva from the fetters of presuppositions and from the bonds of Impotence.

Meditation practice is also covered in detail in Chapter XIII of the 7 In this exposffion, have followed mainly the text translated by E Lamotte: Samdhtmrmocana-sutra, L'exphcation des Mysteres. Texte Tlbetam edlte' et tradL11t par Etlffllne Lamotte Uruverslte' de Louvaln, 1935 The eighth chapter runs from pages 209-236 also kept Into account Xuanzang's translation Into Chinese, which IS five volumes, in particular, the chapter on meditation, the "Fenlne yupapzn" which the Sixth chapter the Chinese version.

Yogacarabhumt.8 Substantially in line with the exposition contained in Vlll of the Samdhnirmocana, it explains that the essence proper to the daygna as cultivated by the Bodhisattva is described as being supreme spmtual concentration, mundane and supra-mundane, haung the premise of listening to the sutras and sastras and the personal reflection on their content. The stabilization of the spirit possesses as its essential constituents either calmness of the mind, samatha, or introspection, vipasyana, or both at the same time, being a two-tiered path to enlightenment In fact, thyana as centered on the double principle of samatha and vipasyana is compared to a vehicle pulled by two horses under a yoke.

As mentioned above, meditation in the Yogacara IS based on the Bodhisattva ideal and provides for a process divided into ten stages, the so-called ten stages of the Bodhisattva, which fit Into the scheme of the

To follow the order given in the Pramanasamuccaya, the Lankavatarasastra and the Abhitharmasamuccaya,ll the Five Paths are the Sambharamarga, the Prayomarga, the Darsanamarga, the Bhavanamarga and the Nzsthamarga. The Ten Stages of the Bodhisattva's cultivation fit into th1S scheme and comprise the third and fourth paths.

In Vasubandhu's Rebirth Treatise [Sukhavativyuhopadesa] the cultivation process is articulated into Five Gates, which remind us of the doctrine of five Stages described above. These are Bodily worship, Verbal recitation, Mental resolve, Visualization and Transfer of merit.12 Vasubanthu explains that the first four perfect the virtue of Entry (i.e. into Nirvana), while the fifth perfects the virtue of Departure (i.e. the return into the world to save other living bangs). This is consistent with Vasubandhu's explanation that the first four are for the benefit of oneself, and the fifth is for the benefit of others. The most important of these gates is the fourth, visualization, and the bulk of the treatise IS dedicated to it. Its importance lies in the fact that through It asraya paravrtti is achieved, to finally enter Nirvana In the Transfer of merit, or the Nisthamarga stage. Vasubanthu's Rebirth Treatise sheds some light on the type of religious practices Yogacara monks used to perform in India. As mentioned

Dhannanægha [Stage of Dharma Clouds]

11 Hayashlma, Osamu "Yu_1sh1k1 no shltten" The Practlce of Mind-Only] Koza Dat1Ö BukkYÖ Lectures on Mahayana Buddhism], No 8 Yuisl-ukl The Thought of Mmd only] Tokyo ShunJûsha, 1982

12 1 have followed here the translation of the terms given In Richard K Payne's "The Five Contemplative Gates of Vasubandhu's Rebirth Treatise as a Rltuahzed

Visualization Practice" m The Pure Land Tradition History and Development (Ed J Foard,

M Solomon, and R K. Pame Berkeley Buddhist Studies Senes 1996, pp 232-266)

earlier, meditation for the Yogacara runs on the binary system of samatha and vipasyana. We can verify it here. The practitioner, after making prostrations—probably in front of some Image of Mattreya or Amitayus— calls the name of the Buddha, and seeks to calm the mind while sitting in meditation. Calming the mind is also a means to reach perfect visuahzafion.

The system of Five Paths was definitely systematized by Dharmapala (?-?), and afterwards mfroduced to China by Xuanzang (622-664). The authority enjoyed by the Chnese pilgrim leads us to think that this system probably achieved great prominence within the Faxiang clergy in China and, perhaps, in Korea and Japan. As we see from the above exposition, there is substantial identity m the methods of meditation described in the works just exammed, which are among the most representative of the school. The basic scope of meditation was that of rebirth in Buddha's paradise, be It Tusita or Awitabha's Land of bliss. After having reached the stage of enlightenment, the practitioner might renounce it to divide the merits accumulated With other living beings so that Nzwana could be reached by as many people as possible. All this was in perfect accordance with the Bodltsattva ideal propounded by all other Mahayana Schools and it was also reflected in the tradition of the Faxzang school in the whole of East Asia. The goal of rebirth m the land of bliss was attained not only through meditation but also through acts of devotion, such as prostrations, calling the name of the Buddha, penitence, charity and the strict observance of monastic rules, but more details on these aspects will be covered In the second part of this article.

Yogacara-Fmang

The Patheon

In Korean history, the cult of the Faxiang sect has been centered mainly on the figures of Maitreya (who occupies the central place in the pantheon), Amztabha and Ksitigarbha. It seems that the cult of Maitreya appeared first with strong Hinayana connotations and was later gradually absorbed into the Great Vehicle.13 According to the Biography of Vasubanthu written by Paramartha,14 Maitreya Inspired many works attributed to Asanga—the most important of which being the Yogacarabhumi—that have later become the basic texts of the school. Paramartha played an important role in fransmitting the Yogacara school's Maitreya cult to China, thanks to his translation of the Biography of Vasubandhu and other important books of the school. The cult of Amitabha is also very ancient, which is evidenced in the Prologue of the Samdhimrmocana-sutra and in the Rebirth Treatise of Vasubanthu. We also find proof of this cult in connection with the Faxzang school, both in China and Korea. Quite differently, the cult of Kszfigarbha seems to have been absorbed later into the Yogacara-Fmang tradition, since its faith had a great development mostly in Central Asia and from there it must have reached China around the IV century A.D.15 Let us now examine

13 The fnst works In which the figure of Maltreya appeaxs are the Pali Cakkavatfislhanadasutta, the Maltreyavgdana, and the Suttanzpata Another feature of the characterization of Maztreya that those who attend his "three assemblies" become arhats and not bodhisattvas Jan Nattier "The Meanmgs of the Mattreya Myth." Sponberg A, and Hardacre H. Maztreya, The Future Buddha pp 23-47. 14 Tazshö Vol 99. p.188

15 In the fangzhz Records of Buddha Land], Daman 596-6671 states that Ksthgarbha's cult was already present In China durmg the Jin Dynasty (265-316) However, Its association With the Yogacara-Faxtang tradition must walt until

one by one these figures of the pantheon and their relevance to the history of the sect.

The figure of Mattreya appears some of the most important sutras of the sect's canon, such as the Samdhinirmocana (Chapter WII), where Mattreya takes the center stage with the Buddha. 16 We can find proof of Mattreya's cult In a number of commentaries written by monks of the school on the Mattreya sutras. In addition, there are a few references to It In the travel records of Chinese travellers to India, such as those of

Faxian, Xuanzang's Records of Travels to the West and the records of Ijing. 17 References to this cult are contamed in many biographies of enunent monks of the Yogacara-Fanang tradition, including also those of the the Sul and Tang dynasties

16 Many facets of the cult of Maztreya have been studied Ln detail by several scholars However, their research has not been specifically oriented towards clarifying Its relevance to the cultic aspects of the Yogacara-Faxzang tradition—O Hyeong-geun [k "Yuga yuslk-eul tonghan Mreuk smang Jeollae" (Wk, The Transmission of Maltreya's Cult through the Yogacara Welsh], "Szlla yuga sasanguk Jeon„gae-wa Ml_reuk smang" [*fiZ fl$j•fäfl], The Development of the Yogacara Thought m Silla and the Cult of Maztreya] Yuszk-gwa stmslk sasang yeon-gu 'IX.ËÆ, Studies on Washi and Mind-On]y Thought], Seoul Bulgyo sasangsa, 1989, pp 459-517, Sponberg, A, and Hardacre, H Maztreya, The Future Buddha New York Cambridge Umverslty Press, 1988 The cult of Maltreya was well established l_n all the Buddhist sects of Indža at the beglnnmg of the Christian era Concernmg Its orlgtn, Basham suggests that It nught have ansen follomng contacts between Zoroastnarusm and Buddhism when India was occuped by northwestern Invaders In Zoroasffiarnsm, we find the Idea of a cosnuc sasnour, Saoslant, who thought to brmg uruversal peace and harmony Kitagawa, J M "The Many Faces of Maltreya " Sponberg A, and Hardacre H Mattreya, The Future Buddha pp.IO-II

17 Legge, J A Record of Buddhsfic Kangdott£ Oxford, 1886, Datang xtyu]l Izaozhu BelJkng Thonghua shyu, 1985, Nanhat qzgut nezfazhuan paozhu

BelJ1ng Thonghua shyu, 1995 Shelun sect.

The propagation of Mmtreya's cult within the Yogacara-Faxiang tradition goes together with the diffusion of the Yogacarabhuml. Many scholars of the school wrote commentanes and treatlses on It, starting with Vasubandhu, whose Treaty tn the Thirty Stanzas [Tnmstka] is based mostly on this commentary, and the great logician Dignaga encouraged his disciples to study it. We have also a few practical cases where monks voiced their veneration of Mattreya. Besides the case of Asanga, who met directly With Maitreya, his younger brother Vasubandhu also venerated the Bodhisattva in the Mahayana Samparigraha-sastra by saying: "He will always be my Teacher and I will serve the Saint Maitreya.

Another testimony is given by Xuanzang in his travel records (Vol. 12), when he relates that Dharmapala, in front of the statue of Avalokztesvara in the Temple of the Bodhi Tree, expressed his wish to see Maitreya.

The Importance of the Yogacarabhumi was recogruzed by Xuanzang, whose primary motive In going to Intha was to find a complete and original version of the treatise. Xuanzang studied the Yogacarabhumi directly from the old Silabhadra at Nalanda. Chinese monks of the Faxzang sect and Silla monks active in Tang China kept up this Indian tradition and wrote a series of commentaries on it.

The cult of Maitreya is closely related to that of the Tusita Heaven,20

where usually the monks of the Yogacara-Faxzang fradition prayed for rebirth and where Maitreya resides waiting for the right time for his descent into this world to save all sentient beings. Korean scholars roughly distinguish between two types of Maitreya beliefs, those ascent and those in descent. Of these, the first belongs undoubtedly to the Yogacara-Faxzang tradition, while this does not necessarily seem to be the case with the second type.

Many monks of the Faxzang sect prayed to be reborn m the Tusita heaven, at the side of Maitreya. Perhaps the most famous example in China IS that of Xuanzang himself, who prayed to Maitreya when he was assailed by pirates on his way to Prayaga [the modern Allahabad] on the Ganges. Feeling threatened, Xuanzang meditated upon the Bodhisattva

20 The Tuszta-deva is one of the SIX Heavens of Deszre, where there are the Castel of the Seven Treasures and an Luùnuted number of celestial bemgs llvmg together It IS divided Into two abodes, the Outer and the Inner Abode The first IS Inhabited by the multitude of celestial bangs, while the second IS Maetreyds pure land Mattreya lives there preachmg and waiting his tame to descend and save all 11V1ng beings

Maitreya. Suddenly a furious wind started to blow causing billowing waves to sink the boats. The pirates, frightened, set Xuanzang free.23

Ijing also expressed his devotion to Maitreya in very passionate language: "Deep as the depth of a lake be my pure and calm meditation. let me look for the first meeting under the Tree of the Dragon Flower when I hear the deep rippling voice of the Buddha Maitreya."24

Unfortunately, the destruction in the wake of the persecutions of the Huichang Era (841-846), as well as repeated invasions and internecine wars, make it difficult to find any archaeologcal remains related to the cultic aspect in China.

We have also several instances of Silla monks who expressed their deep devotion towards Mattreya. Famous is the case of Taehyeon, who would pray and walk around the statue of the Bodhisattva, and as he moved around, the statue would also turn Its face to look at him.25

The case of Jmpyo is also very well known. The Sarnguk yusa relates that Jinpyo went through a long period of expiation and prayer until he received a set of the Vlnaya directly from Ksitigarbha. Not content with this, he went on with his expiation until Maitreya himself descended from Tusita to give him 189 vinaya sticks, which were handed down for many generations. After this, he carved a huge statue of Maitreya, which became the most important obJect of worship.26 Mmtreya statues

23 René Grousset In the Footsteps of the Buddha. Trans J A Underwood New York,

1971, pp.127-8. Quoted In Joseph M Kitagawa, "The Many Faces of Maztreya," p 11 24 Slr Charles E110t. Hnduæsm and Buddhism, 3 Vols New York, 1954, 2.22. Quoted in Joseph M Kitagawa. "The Many Faces of Mmtreya." p 11 25 llyeon "Hyeon yuga hae hwaeom" Yogacara Master Taehyeon and

Huayan Master Beophae] Samguk yusa, Book 5 are still found to this day in all temples with a Faxzang background.

In temples belonging to the Faxtang sect in Korea It is often possible to see immense statues of Maztreya towering on the surrounding buildings, as is the case With the Yong-jang, Geumsan, Beopju and Anyang temples. 27 In some cases these statues of Maitreya are Inside two/ three-story halls that bear the names Mattreya Hall or Dragon Flower Assembly. The presence of these three-story pagodas housing statues of A/laitreya and symbolizing the three final assemblies of the Bodhisattva in most Fax-tang temples of Korea is noteworthy. It suggests that the

ascent to Maitreya's paradise might have been reserved for chosen groups of monks, while the descent cult was stressed at Faxzang temples in order to attract the masses of common believers. On the one hand, this allowed for the realization of the Bothisattva Ideal of transfer of merit, on the other hand, the laity would provide the basis for the livelihood of the monastic community. We can testify to the Importance and depth of belief Maitreya, both the ascent and descent types, through the wealth of cornrnentanes that 26 llyeon "Jznpyo-jeon-gan" Jtnpyo hands Down the Dlvmatlon Sticks] Samguk yusa, Book 4

27 The statue of Mmtreya at Yongang Temple made of stone and IS about 20 meters tall The wooden M.aitreya at Geumsan Temple IS about 12meters tall, but this IS a reconstruction of 1627, perhaps on a smaller scale, made following the destruction by fire dunng the Japanese Invasion of 1592 If we consider that one of the names the hall was "Yuk]angeon" (yulqang being a little less than 20 meters—I Jang IS 3 30m), the statue must have been about 20

meters tall. Beopju Temple also has a very recent reconstruction of Mattreya m bronze We know from the Dongguk yeop seungnam that It was about 20 meters tall Anyang Temple's statue of Maltreya has been moved to Yonghwa Temple, Anyang City, Gyeongg Provmce Its size was also 6 jang From the above we can Infer that most, If not all of these statues must have been housed m three storey bulldmgs, symbolm_ng the Maztreya descent myth have been written on the Maztreya sutras in China and Korea, such as

Kuiji's Praese to the Ascent of Mattreya to Tusita Samadhi-sutra,28 A Short Praise of the Maitreya Ascent Sutra29 (written by Woncheuk), A Commentary to the Mattreya Ascent and Descent Sutras30 (written by Wonhyo), A Commentary on the Three Maztreya Sutras31 and others (written by Gyeongheung), and An Account of Old Traces of the Maitreya Ascent Sutra32 (wntten by Taehyeon), among others.

Amttabha's faith is another important aspect of the cult practiced by the Yogacara-Faxiang monks. As pomted out in the first part of this article, the Prologue to the Samdhinirmocana-sutra is a description of Sukhavati, and th1S is enough to provide an idea of the importance attached to Amitabha's faith by the Yogacara masters. A practical exemplification of th1S is found in Vasubandhu's

Rebirth Treatise, where the central figure is Amitayus. Of the Ftve Gates of Meditation the Treatise deals with, in the Third, Dharsanamarga, the practitioner resolves to be reborn in the Western Paradtse, and in the Fourth, Bhavanamarga, he visualizes the ments of Pure land, seezng Amitayus and his retinue of bodhisattvas. It is at this stage that the fundamental fransformation of the mind is achieved and the gate open to final deliverance.

In China, the large number of commentanes that have been written on the sutras dealing With Amttabha's faith is a demonstration of the Importance that was attached to the cult of Amztabha by Faxiang monks. The author of Further Biographies of Ennnent Monks33 states that Tanqian

28 Guan Mlle shang nan Tushufian ltngzuan T 1772

29. Mreuk sangsaenggyeong yakchan not extant

30 Mreuk sanghasaenggyeong-so not extant

31 Sam Mweukgyeong-so T 1774

32 Mreuk sangsaazggyeong gojeok-g

(542-607), the famous rnastffl• of the Shelun Sect, dreamt of the beauty of the Pure Land of Armtabha. In the Fmang tradition we can quote Kutll's Commentary and General Praise to the Amttabha-sutra34 (popular among Faxiang monks of the Mddle Goryeo Penod35), the Commentary to the Amitabha-sutra36 and the General Principles on

Dispelling Doubts on the Fundamental Meaning of Pure land 37

Another proof of this cult's connection with the Yogacara-Faxzang tradition can be evidenced tlm«ough the records of Ennin's travels In Tang Thina. In one section of the journal Ennin describes his visit to Tongzi Temple, which IS about twenty kilometers west of modem Taiyuan.

There, inside a two-story hall, he saw an relating a story about the founder of the Temple, the Meditation Master Hongh, who in the 7th year of the Ttanbao Era (Northern Q, 556), witnessed a cloud rising to the sky carrying four children seated and playing on lotus flowers. A sound shook the earth, and cliffs crumbled and fell. An image of Amttabha appeared where a bank had fallen away. Following this vision, a huge image of Amitabha was carved (about 30 meters high), flanked by the bodhisattvas Avalokitesvara and Mahasthamprapta. Later, a few decades before Ennm, Xuanzang's disciple Kuijz had come to the temple from aungan to lecture on the Washi-lun38 and resided

33 XuGaosengchuqn Book 18

34 Anntuojzng tong-zanshu T 1758

35 See the [Geumsan Temple Stone Inscription of

Hyedeok Royal Preceptor Sohyeon], written by Glm Bu-slk Chœen lansekz stjrgn [General Overview of Korean Epigraphy], No 92

36 Amztuopngshu

37 Xzfang yague shzyz tongguz T 1964

38 See Ennzn's Diary, The Record of a Pilgrzmage to Cuna m Search Of the Law (Trans

Edwin O Raschauer New York The Ronald Press co, 1955, pp 272-3)

there for several months.

In Korea, there is also some clear evidence in Yogacara-Faxiang temples relating them to the faith in Amitabha. The Samguk yusa relates the story of how in 719 Gim Ji-seong, a sixth-rank Silla official, had a temple called Gamsan built on one of his lands in memory of his deceased parents and for the well-being of all his family members. Gamsan Temple was built on Namwol Mountam, not far from Bulguk Temple. For that occasion, Gim Jr-seong had stone statues of Maitreya and Amitabha placed in the Golden Hall [Geumdang] of the temple. This can be confirmed by archaeological evidence, as these two statues along with their inscriptions have been preserved. They are included in the Clœen kinseki swan. In carving these statues, Gtm Ji-seong was certainly following a well established tradition at the school. We can thus observe that the couple Maitreya-Amitabha was the main object of worship at Gamsan Temple. The same can be argued for Yongang Temple, where a pair of statues are present, although we are certain only about the identity of Mattreya, while it is not yet sure whether the other is Amitabha.

Additionally, the great concern that the Yogacam-Fmang monks had toward the Amitnbha cult is also demonstrated by the wealth of commentaries on the Sukhavattvyuha and related sutras. We will quote a

few of these, starting With the Commentary to the Sukhavattvyuha- sutra 41 the Commentary to the Amttabha-sutra42 written by Woncheuk, the Eulogy to the Sukhavatwyuha-sutra Written According to its Meaning,43 the Abbrevtated Records of the Awntabha-sutra,44 Gyeongheung's Commentary to the Sukhavafivyuha-sutra,45 HyeomZ's [Commentary to the] Records of the Sukhavativyuha-sutra,46 Doryun's Commentary to the Alli1tabha-sutra,47 and

Taehyeon's Records of Traces of the Sukhavatwyuha-sutra 48

This tradition continued dunng the Goryeo Period (918-1392), as IS possible to observe with the Inauguration of the Hyeonhwa Temple (1011), when a rellglous ceremony was held honour of Amztabha. The service lasted three days and three nights49 and was held on a regular basis at the temple thereafter. At Geumsan temple's Gwanggyowon, the Faxiang monk Sohyeon published, at the request of Llzcheon, a series of works, 20 books in all, relating to the Amttabha sutra.50 Another reference to Amztabha's cult IS found in the Sujeong Society of Mt. JIH, where adepts prayed to be reborn in Amttabha's Westenz Paradese.51

41 Muryangsugyeong-so not extant

42 Anutagyeong-so not extant

43 Muryangsugyeong yeonuz subnunchan T 1748

44 Amttagyeong yakki not extant

45 Muryangsugyeong-so not extant

46. Muryangsugyeong-gz(-so) 2 books only the first žs extant Sokuzdcyö vol 32, Book 2

47 Ametagyeong-so not extant

48 Muryangsugyeong gojeok-g

49 "Gaeseong Hyeonhwasa-bl (Eumgl)" eÉd)] ChŒen kmsekl swan pp 241-252 Hyeonhwa Temple was the ma_l_n seat of the sect durmg the Goryeo Penod 50 "Geumsansa Hyedeok wangsa pneung tappl" C}lœen kmsekl

swan, Vol 1 pp296-303 Yogacara-Fmang

Furthermore, fragments of inscriptions relating to the cult of Amitabha have been recovered at Beopcheon Temple, near Wonju, though their dating is still quite problematic.52 This temple was one of the most important centers of the sect during the Middle Goryeo Period.

The cult of Ksthgarbha also occupied a very important position in the tradition of the sect in Korea during the Silla and Goryeo periods. The figure of this Bodhisattva is usually associated with a kind of divination that more or less resembles the type described in the Sutra of Dwmation Relattng to the Retnbufion of Good and Bad Acts,53 hereafter referred to as the Divination Sutra. It is difficult to say, however, whether it had an Important place in Thina's Faxiang tradition The first relation to Ksitigarbha's cult comes from Smbang, a Szlla monk of Cibez Temple54 regarded as one of the most important pupils of Xuanzang, for he, together with Kuiji, Jiashang and Pukuang, actively participated in the Chinese pilgrim's enterprise of the suffas. Sznbang, as a

51 Gwon, Jeok "Jmsan Sujeongsa-gl" Record of the Stqeong Society of Mt Jin] Dongmunseon Book 64

52 Beopcheon Temple's Mup Year Inscription on the Halo of the Altar "Myamyeong Beopcheonsa Gwangmyeongdae" Ed Hwang Su-yeong Han-guk geumseok yumun Remams of Korean Stone Inscnpfions], No 295 Seoul Ilpsa, 1976-1985, "Mupmyeong Beocheonsa hyeonro" Beopcheon

Temple's Muja Year Inscnpfion on a Hangmg Burner] Ibid, No 296, "Mujamyeong

Beopcheonsa beonamyeong" Beopcheon Temple's Mya Year

Burner Inscription] Ibid , No 359, "Mupmyeong cheongdong hyangwan" Mup Year Inscription on a Bronze Incense Bowl]. Ibid, No 360

53 Jeomchal seonakeoppo-gyeong T No 09

54 We do not know the exact dates of Smbang, but he must have come back to Szlla after staymg for a long penod In Chl_na, for he IS referred to as "the Sillg monk from Hwangnyong Temple" (which was in Gyeongu) by the Japanese monk Genshzn (942-1017)

In h1S Ichyo ydetsu Fundamental Prmaples of the Ekayana]

specialist in the Mahayana Great Collection of the Ten LMaeels Sutra [Dacheng dap shilunjing]—hereafter referred to as the Ten Waeels Sutra wrote the commentary to lt. The translation of the sutras relating to the cult of Ksitigarbha gave a strong impulse to the Sect of the Three Stages [Sanjiejiao]. Along these lines, Sinbang is also said to have lectured frequently on the Ten Wheels Sutra, and Fus interest in the cult of Ksitigarbha made a decisive contribufion to the development of the Sect of the Three Stages, so much so that Sinbang is remembered as one of the sect's patriarchs.55

Another Silla monk connected to the cult of Ksitigarbha is Won-gwang (555-638). In China, he studied the doctrines of the Shelun School at Changan together with the cult of Ksitigarbha and its associated practices. These practices were probably widely followed in the Shelun temples at that time In China. Therefore, Won-gwang must have also come in contact with the monks from the Sect of the Three Stages, and even with Sinbang himself. Returning to Stlla, he introduced the practices of divination associated with the Divination Sutra. Th1S cult established itself at the Gaseo Temple during Won-gwang's lifetime and a Divination Fund [Jeomchal-bo] was put in place to pray for the well-being of the King and to ward off evil. In Silla we have a few other instances where divination is practiced, but it is difficult to discern, as is the case with Won-gwang, whether they bore any relation to the Faxzang Sect.

55 This sect was founded by the monk Xznxmg [fifi, 540-5941 during the Sul Dynasty See Yabukl Kelkl [R-I]kE, Sangazkyö no [ A Study of the Sect of Three Stages] Tokyo, 1927 Quoted In Thae, In-hwan "Smbang-gwa Silla Bang yecham gyobeop" Smbang and Ksthgarbha's Perutence Rituals In Szlla] Han-guk bulgyohak No 8 pp31-52 However, the fact that

Smbang mcluded m the list of the ancestors for the Sect of the Three Stages makes

Yabukl doubt that the translator of the Ten Wheels' Sutra and Smbang are the same

Yogacara-Faxiang

The practice of divination associated With the faith In Ksthgarbha became very popular in Silla in the VIII century through the activities of Jinpyo. He is one of the most famous monks in the Korean history, and his bi0Baphy IS recorded in the Song Gaosengchuan. After Jinpyo, many other monks, like Surge, Jinpyo's preceptor at Geumsan Temple, must have fraveled to China and visited temples where the cult of Ksztzgarbha together with divination were practiced. Sunje studied under the guidance of Shandao Sanzang (613-681) and later received the Five Precepts [Wujie] directly from Manjusn on Mt. Wutat. I)uring his stay in China, Sunje must have come in contact with the Sect of the Three Stages, and later handed down to his disciple, Jmpyo, the doctrines he had learned in China.

When Jinpyo injured himself in the course of his expiation practices, Ksitigarbha healed him and gave him a monk's robe, an alms bowl and a set of the vinaya. Compared to Mmtreya, the figure of Ksitigarbha seems to have occupied a secondary place in Jmpyo's religious world, but the presence of this cult had spread to many Faxiang temples during the Goryeo Period. Jznpyo spent the rest of his life propagating the doctrines. He renovated Geumsan Temple at Gimje and founded the Gilsang Temple on Songm Mountain. His disciples spread, propagating the doctrine among the common people. In addition, the disciples founded the Baryeon Temple on Geumgang Mountain and, some generations later, Donghwa Temple, in Northern Gyeongsang province.

With Jznpyo we find an unequivocal connection between the Faxiang Sect and the Kszttgarbha cult. The influence Jmpyo exercised on the religious atmosphere of the country and abroad appears to have been significant. During the Goryeo Penod, one finds the practice of divination clearly associated with Faxuzng monks and temples, as in the

cases of Songni Temple, the Tustta Institute [Dosolwon] in Gaegyeong and the Sujeong Society on Mount Jtri. Goryeo: Religion in practice

Religious practice In Faxiang temples likely followed the meditation methods described above and, from a devotionalist viewpoint, the veneration of the pantheon figures previously discussed.

However, the description of Faxiang religious practice would be incomplete without mentioning the rituals implemented by the Faxiang communities. To this end, it would be useful to distinguish three dimensions religious practice: a political one, which implied lecturing on sutras at court by monks of the sect (such as the Avatamsaka, the Benevolent Ktng Sutra, and others); the celebration of

religious functions, and the participation of Faxiang monks at official ceremonies (such as administermg vows to the king and queen, reading invocations and prayers to propitiate rainfalls, and casting spells to relieve epidemics and famine and defeat enemies). This can be ascertamed mainly through analyses of stone inscnptions. Here, one can quote cases like that of the National Preceptor Jeonghyeon, who lectured repeatedly on the Geumgogyeong (Geumgwang myeongyeong) In court (1046-1048), or

Haerin, who presided at the Assembly of One Hundred Seats court in 1059 58 Sohyeon lectured on the Benevolent King Sutra [Inwanggyeong] as part of a ceremony to Heaven In 1095,59 while Gm Deok-gyeom lectured on the Geumgwang myeongyeong at court during King Inpn<s reign,60 and participated in the divination ceremony [jeomchalhoe] that was held at Songni Temple during the last years of Inpng's reign to propitiate the health of the

king. In 1170 another divination ceremony was celebrated at the Dosol Institute to soothe the spirits of the 11terat1 who had been killed dunng a military take-over 61 The divination cult practiced by Jinpyo and his followers had mainly been a provincial phenomenon duxmg the Silla period but was now officially accepted by the royal family and the military rulers. Much later, Hyeyeong lectured on the Benevolent King Sutra at Wanshoust in Dadu in the year 1292,62 and Misu lectured on the Prajnaparamtta Sutra as well as on the Visualization of the

58 "Stupa and Inscription of Beopcheon Temple's National Preceptor Jzgwang at Wonju' [Won}u Beopcheonsa Þgwang guksa hyeonmyo tappl, ChŒen kznsekz swan, pp 283-291

59 "Stupa and Inscription of Geunßarz Temple's Royal Preceptor Hyedeok at Gzmje'

[Geumgu Geumsansa Hyedeok wangsa pneung tapp,

Chyn kensekz swan, pp 296-303

60 Epitaph on Gim Deok-gyeom's Tomb" [Gim Deok-gyeom myoJ1_myeong,

Ed Yl, Nan-yeong Supplement to Korean Stone Inscrzpfions [Han-guk geumseokmun chubo, Asea munhwasa, 1976, pp 123-125

61 Gl_m, Bu•slk "Notes on the Div-mafion Meetl_ng at Song:nl Temple "

Dongmunseon VOI 110; Yu, Hul [31m] "Notes on the Divinatlon Meeting at Dosol Instltute" Dongmunseon Vol 110. Dosol means Tuszta and the Dosol Institute was an annex of Sunggyo Temple [¥k#], one of the most Important of the Beopsang temples of the capital

62 "Stupa and Inscription of Hongjm National Emtnence at Donghwa Temple l_n Daegu" IDaegu Donghwasa Hongpn guk-jon jineung tappl, azŒen kznsekl saan, pp 596-598

Stage of the Mind Sutra In 1308.63 These were the political dimensions of religious practice, which themselves through the celebration of official rites and pomp at court. They assured political protection, social connections with the aristocracy and econorruc privileges to the monastic community.

A second dimension concerns the path of cultivation followed by the Individual monk within the premises of the cloister: meditation, prayers m front of the statues of Mattreya, Amtabha, Ksitigarbha, and Avalokitesvara, lecturing on sutras, copying the sutras by hand and practicing various forms of penance. For

instance, we can imagine that, as in Taehyeon's case, circumambulation of Maitreyds statue must have been an essential part of daily worship,64 even though the exact content of the recited prayers is unknown. It is likely, however, that on such occasions excerpts of the Maitreya sutras were read. In this regard, an important aspect is the sfrengthening of the sect's Identity and the sense of belonging on part of the monks. On the one Side this was obtained through the

study of sutras and commentaries of the Yogacara canon (in this regard, one should not forget that during the Middle Goryeo period Sohyeon published at the Gwanggyowon in Geumsan Temple, the sect's sutras and commentaries) and on the other side tluough the veneration of the sects' SIX Goryeo Patriarchs [Haedong yukjo], among whom, dunng Sohyeon's time, were the figures of Wonhyo and Taehyeon. The names of others are not quoted, and while we cannot be certain about 63 Slmpgwan-gyeong-g In "Stupa and Inscription of National Emmence Japong at Boeun's Beopju Temple" [Boeun Beop]usa neong gukjon bomyeong tappl, (Chœen ktnsekt sœan, pp 486489).

64 Ilyeon "Yogacam master Taehyeon and Hugyan nnster Beophae" [Hyeon yuga hae hwa-eom, Samguk yusa Book 5

PUGGIONI • Yogacara-Fmang

the identity of the remaining patriarchs, Jtnpyo surely must have been included. Among the Chinese patriarchs of the sect were Xuanzang and Kulli. Their images were hung in temple halls of the sect and probably were the object of dally veneration and respect.

A third dimension concerns the relation of the sangha to the laity. To the laity, Yogacara monks addressed a wider, more universal message not limited to the salvation of the individual dedicated to meditation; rather, it had as Its main obJective the salvation of the many. Th1S is the dimension where the Mahayana ideals of the Bodhisattva and of the transfer of merit are realized. Related to it are many forms of the cult as participated in by the laity, such as

ceremonies inside the temple, the lecturing of sutras, sermons, ceremonies that last several days and months, collective forms of prayer and penance, processions, assistance for the bereaved, and prayers for the dead. In this respect, the towering statues of Mattreya that are still found today in some of the sect's temples Indicate the power of the cult; no doubt the cult drew considerable crowds and commanded the reverential respect of the faithful. The grandiose statues of Maitreya were usually housed In buildings adorned with roofs, each representing one of the three final assemblies to be held by the Maitreya to save all sentient beings before the end of the world.

The cult of Maztreya is also associated with the practice of divination. This IS true at least in Jtnpyo's case, and probably true for his disciples as well. This practice corresponds more or less to the description given in the Dwination Sutra, the only differences bemg that they were passed down by Maitreya and not Ksitigarbha and the 8th and 9th sticks were held to be more important with respect to the others Wooden sticks are thrown on the floor front of a statue of the Buddha and, according to the results people expiate from days or even up to 40 or 90 days. The ideal result IS when the 8th and 9th sticks drop in an upright position in front of the Buddha's statue. When the 8th and 9th sticks are covered by the others It rœans that bad karrm IS sull overwhelmingly present and a further period of expiation is required. Thus, this practice could continue for a long intervals of time.

One of the most exemplary illustrations of this practice IS represented by the Sujeong community of the middle Goryeo period In this case, practitioners would throw the sticks on the Bound, possibly In front of a statue of Amitabha, to divine good and bad karma. The sticks were then returned, according to the response, into two boxes, one for good Karma and the other for bad. According to the prescriptions of the Dtvznatzon Sutra, this procedure was repeated every fifteen days. The names of all the participants—even the dead—were inscribed on the sticks. All those who received a favorable response commenced a period of

expiation on behalf of those whose karma was still unfavorable. The penod of expiation went on until a favorable response was given to everyone. The process was repeated each year for fear that those who had favorable responses earlier might now have accumulated bad karma. This practice must have been followed, with minor differences and peculiarities, by most of the temples In the Faxiang sect during the Goryeo period. The same can be said of Anntabhds cult, object of an array of prayers, votive offerings, and other religious functions that had as its object rebirth in Western Paradise. Such was the case with the earlier mentioned Silla monks Nohll Budeuk and Daldal Bakbak,65 who are

65 "The two saints of Mount Nambaegwol, Nohll Budeuk and Daldal Bakbak"

quoted in the Samguk yusa. During the Goryeo period the Amttabha sutras must have been held in high esteem as they were copied quite often by scribes, even though only two copes still exist.66 Not directly relevant to our discussion but useful in understanding the religious spirit of the Latter Goryeo is the abundance of sacred images depicting the descent of the Buddha Amttabha.67

Veneration for the figure of Maitreya was most often accompanied by the cult of Kstfigarbha, which was related to the other-world, the innate fear of death and what comes after death. We should not marvel, therefore, at finding its cult in association with the most disparate practices of penance. Among them, one can perhaps find the earliest practices of divination associated With a religious context in the East Asian Buddhist communltles. This practice attracted many

people. During the Szlla period the cult of Ksitigarbha IS documented only in the provinces and is related to the figures of Jmpyo and his disciples. L)urmg the Goryeo period this cult continued to be associated With the same temples and also with some others in the capital area, such as the Tustta Institute.68 With the cnsls of scholastic Buddhism which followed

[Nambaegwol Yiseong Nohll Budeuk Daldal Bakbak, — Samguk yusa, Book 3, "Stupas and Images," Book 4 66 Gwon, Hui-gyeong Studzes on Goryeds Written Manuscnpts [Goryeo sagyeong-ul yeon-gu; ff3ž] Seoul Mljmsa, 1986 67 "Nflta raeyeong-do" Buddhist Pazntzngs of the Goryeo Dynasty [Goryeo skdae-ul bulhwa, ff*] Seoul Slgongsa, 1996 68 "Remarks on the Divmabon Assembly at Tusžta Institute" IDosolwon leomchalhoeso;

Dongmunseon, Book 110 The Tuszta Institute was an annex to Sunggyosa, one of the most Important Faxtang temples In the capital "Foreword and

Inscnpfion on the Bell of Tuszta Institute" [Dosolwon Jongmyeong byeongseo, Dongmunseon, Book 49

the revolts of Yi Ja-ui, Yi Ja-gyeom, Myocheong and the military coup-d'État about half a century later, the divination practices associated With the cult of

Ksttigarbha were absorbed by the Sujeong Society which sprouted during Injong's reign and continued to prosper until the fall of h1S kingdom and perhaps even later. We can, therefore, safely assume that the stream of Jznpyo's faith and its associated temples represent an element of popular Buddhism within the Faxzang fradition in Korea

The above mentioned practices of penance have great relevance especially when people are convinced to live in the final age of the Doctrine. Such was the case during the period of Mongol control. At that üme many comrœntaries reflecting the doomed religious atmosphere of the period appeared and they are a testimony to the kind of faith practiced by Faxiang monks and the laity that flocked to their temples. Among them we can quote the Explanation of the White-robed

Avalokitesvara wntten by Hyeyeong and Msu's Commentary on Rituals of Mercy and Expiation.

In Hyeyeong's case the practice of penitence is associated with the figure of Avalokitesvara and Naksan Temple.69 Thanks to the official adoption of Lammsm as the state religion by the Yuan, this temple, situated in Gangwon Province, was a famous pilgrimage Site, especially during the period of Mongol confrol. A famous statue of Avalokitesvara was located in the temple, and many faithful believers, even from abroad, came to pay their respects to it, Hyeyeong wrote the Explanation to the White-robed Avalokitesvara,70 which is Included in the 6th volume

69 Naksan an abbreviation of Potalakka-san, or Pota[a Mountam, Potata being

Avalokltesvara's paradise

70 The work Incomplete Parts of the introduction and the conclusion are n-ussmg, PUGGION1•The Yogacara-Fmang

of the Corrvlete Writings of Korean Budthism71 and is a commentary to the Avalolatesvara Sutra.72

The work starts with the enunciation of the three minor calamities, or arms, pestilence and famine. The three mtnor calamtttes are proper to the period of the decay of the Doctrine. However, these can be prevented by giV1_ng alms to the needy, offering medicine to monks and observing the precept of sparing the life of living beings—in other words, by following the path of the Bodhisattva.

Penance has a central role in Hyeyeong's work and charity, not to speak of the enjoyment of charitable enterprise, is understood as the best way to follow the Bodhisattva's path. The accumulation of negative karma is due to sins of the body, speech and mind. Accordingly, three rites are celebrated through the figure of Avalokitesvara. These three rites are expressed via eleven stages. Of these, the first one has a general character and is Introductory, while the remaining ten are directed towards specific types of karma. The first three have the objective of destroying bodily karma, through an invocation of the Bothzsattva, who intervenes with his celestial eye. The four subsequent stages are devoted to the destruction of the karma accumulated through speech.

and we are not aware as to the extent of the nussmg parts We can Infer Its authorship from a reference in Hyeyeong's stele When he wrote th1S work he was the abbot of Songm Temple (Since 1267) and had been promoted to Buddhist Controller (Seungtong) In 1269, duržng Wonpng's reign According to the Inscription, Hyeyeong wrote the work under request of state counsellor Yu Gong-gyeong The book, being a commentary to the Avalokltesvara Sutra, IS In a smgle volume and was accepted as being the most authoritative by h1S contemporaries

71. Han-guk bulgyo yeonseo Seoul Dongguk Uruv Press, 1984, pp411417 72 This work the 25th Chapter of the Lotus Sutra, but was Widely circulated separately as an Independent sutra

An Invocation of Avalokitesvara, who through his celestial ears hears whatever people say anyvvhere the universe, IS pronounced to obtain his intervention and destroy all negative karma related to speech. In the last three stages the faithful invoke Avalokztesvara's intervention, who thanks to the penetration and uslon of his mind that Imows whatever people think anywhere at any time, destroys all the negative karma accumulated with the mind. Together with this, people express the wish to be reborn in the Western Paradise of Amitabha

In his commentary on the eulogy of the Sixth Stage, and more specifically the third part of the eulogy where the three concepts of emptiness are dealt with, Hyeyeong explains that when one meditates on the parikalpita svabhava, he realizes that it is emptlness. When one meditates on the paratantra svabhava, he realizes that it is emptiness as well and when one contemplates on the panmspanna svabhava, he again comes to realize that this IS also emptiness. Hyeyeong adds, however, that even though we speak of emptiness, the Three Natures are real as they are merely manifestations of the same reality This way Hyeyeong interprets the concept of emptiness from a Yogacarin point of view, as he affirms the reality of the Three Natures which, according to the tradltlon of the school, in then• panmspanna manifestation constitute the ultimate reality. Such a way of looking at the concept of emptiness is only proper to the Yogacara tradition and Hyeyeong fully adheres to it.

Hyeyeong placed the utmost Importance on the practice of penitence. In so d01_ng, he was representing the Faxzang tradition on the one hand, though he shifts the focus of attention from the themes that are proper to Jtnpyo to the Avalokitesvara Sutra, and, on the other hand, he fully interprets the needs of the time, becoming a link between the previous tradition and the figure and work of another great Faxzang monk, Misu.

Misu wrote a commentary on a work that Emperor Lzang Wuth had commissioned to a group of monks to cherish the memory of his deceased queen. Misu's interpretation of the text closely adheres to the tenets of the Yogacara tradition, and this IS also reflected in the fact that his prayers and penances are directed to Maitreya and he desires to be rebom in Tusita Heaven. This differs from Hyeyeong. There is no mention here of any divination practices, but if one

assumes that Msu's background is related to Songni Temple, we might safely conclude that he was following in the footsteps of Jenpyo's traditions. While he upholds a way of salvation for monks based on meditation and adherence to the Ten stages of the Bocthisattva, and on the strict observance of the znnaya, at the same time the dally practice of divination following Jinpyo's traditlon must have been adopted to cater to the needs of the laity Given the complexity of the subject and the lack of space, we have no means but to deal with this separately and extensively in the future.

The existence of these themes in a Fanang environment reflects more general trends in Buddhism at the time In this context the role of repentance takes on special significance. People were in fact convinced they were living in the final age of the Doctrine and believed that they would not be able to attain liberation solely by their efforts. Liberation, then, could be achieved only through repentance and divine intervention. In 1315, a Penitence Bureau was

established and the Faxzang high priest Misu was named as its head. Penitence practices likely were being followed in most of the Faxzang temples in Goryeo, particularly those located In the provinces. This is confirmed by the flourishing of the Supong Society associated with the practices of divination dunng the period of Mongol control. The subject of penance was very popular at the time, as ascertained in the works of monks such as Woncham,73 Gong-am Jogu,74 Mugi,75 and (Thewon76 (an unknown Seon master from Dongmm Temple77), as well as Hamheo Gzhwa78 in the Former Joseon.

By the same token, within a context where it is not possible to reach salvation through one's own capabilities, or solely through the practice of meditation, acquiring merit becomes particularly important. Ment could be gained in various ways, such as through prayers, offerings to the temple and the monastic community, the gathering of funds to build new temple halls, the fusion of bells, the sculpting of statues, as well as the writing of full sets of the canon in gold and silver.

73 Woncham IjtEl wrote the Sutra on the Ascent to Western Paradise [Hyeonhaeng seobanggyeong Complete Wntmgs of Korean Buddhism, Vol 6, pp 861-877 We are not sure whether Woncham was actually a Faxzang monk He could have been a Seon monk who was deeply Imbued With the religious practices of nearby Faxzang temples, IEke the Donghwasa

74 Jog-u [ÎlflE] Expounded Collection of Commentaries on the Practice of Erpzatzon zn

Rituals of Mercy [Jabldoryang chambeop pphae Complete Wrztmgs of

Korean Buddhism, Vol 12, Supplement Vol 2 pp45-155

Eulogy of Sakhyamunz Buddha's Deeds [Seokka Yeorae haengjeok song Complete Wnfings of Korean Buddhism, Vol 6 pp 484-540

76 Chewon E] Bnef Explanatzon of the Vows of Rttes of the Mite Lotus [Baekhwa doryang balwonmun yakhae, Complete Wntmgs of Korean Budthzsm, vol 6 pp570-577 77 [ Bnef Explanation of the Vows of Rites of the Vthlte Lotus [Baekhwa doryang balwonmun yalåae, quoted the Preface to the Expounded Collection of Commentanes on Practice of Expzahon tn Mercy Rituals by Jogu

78 Hamheo Glhwa Prapupararmta's Expeatton Text [Banya chammun,

n. not extant, one book, quoted In the General Record of the Literary Works of Korean Buddhzsm [Han-guk bulgyo chansul munheon chongnok, Seoul

Dongguk Uruv. Press, 1976.

In the above few pages we observed briefly some of the aspects of religious practice in Goryeo's Faxiang monastic communities. We observed how the Faxiang Sect was one of the foremost representatives of some of the major religious trends of the period, such as that of penitence. This important aspect of religious practice was considered by Faxzang monks not only on a practical level but was also analyzed on a theoretical and doctrinal level.

We have seen that one of the most well-documented religious practices in a Faxiang context, divination, varied from one temple to the other. In fact, we find it associated with the figures of Maitreya, Ksihgarbha, Amitabha and Kuanyin. Perhaps it was associated with these figures at different times within the same monastic communities. Unfortunately, there is not enough evidence at present to state this with certainty. However, we are nonetheless offered a glimpse into the multifanous complexity of a religious world of which we still possess a very limited understanding.

Conclusion

In these few pages we have attempted to provide a short outline of the theoretical premises of the Yogacara religious practice, while, with a comparison of traditions from India, China and Korea, simultaneously trying to understand the actual religious practices of the monks who belonged to this tradition. To do this, we Initially tried to grasp, through an analysis of some texts of the canon, the structure and importance of meditation to the Yogacara monks, including what their ideals and goals were. Following that, we attempted an analysis of available literary and archeological sources in order to ascertain the

composition of the Pantheon. We were able to ven_fy the presence of several figures, but those of Maitreya and Amitabha seem to have been most consistent and significant throughout the tradition. An Important place seems to have been occupied by Ksttzgarbha in Korea from the Stlla period onward, though a direct relationship of this Bodhisattva to the Yogacara tradition in India or China cannot be traced with any certamty at this time. Finally, we tned to gwe a cursory Introduction to faith as it was practiced by the monks of the sect within a Korean context. This subject needs more careful consideration in the future, particularly because of the scarce literary vestiges of the Latter Goryeo

Gwen the volumnous amount of literature on buddhism, it has not been possible to check each and every primary source To find an adequate solution to the problems posited here there is no other way but to leave it to future research We refer especially to many practical aspects of the cult, which would need the analysis of an enormous amount of literature, archaeologqcal and artistic remains in all the countries concerned. For Instance, the relevance of the cults of

Amitabha and Ksthgarbha to the Faxzang sect in (Thina is in need of closer examination. The relationship between the concepts of Maltreya and Amitabha, the Tusita and Pure Land paradises a Yogacara-Faxiang context, also should be examined through a careful study of all the canonical literature of the sect. The same may be said of the Importance of the cult of religious figures that seem to have carried n-u_nor roles, such as Avalolatesvara, Mahasthamprapta and others. Meanwhile, the issue of the daily activities carried on by Yogacara-Faxiang monks, what kl_nd of rellgwus functions they served, as well as the prayers offered and in what way they were should be given more careful consideration.

Index of Chinese Character Names

Anyangsa

Baekkojwahoe

Baryeonsa

Beopcheonsa

Beopjusa

Beopsangpng

Bulguksa

Than [[[Seon]], Zen]

Changan

Chungseon

Cibei si

Dadu

Daldal Bakbak

Daoxuan

Donghwasa

Doryun

Dosolwon

Faxlan

Fæaangzong Five Positions five Way Gamsansa

Gaseosa

Genshin

Geumdang

Vol.

Geumgang Mountain Geumgogyeong

Geumgwangmyeonggyeong

Geumsansa

Gilsangsa

Glm Jl-seong

Gimje

Goryeo

Gungye

Gwanggyowon

Gyeonggi Province

Gyeongheung

Gyeongju

Gyeonhwon

Haerin

Huichang

Hyeonhwasa Hyeonil

Injong

Inwanggyeong

Jeomchalbo

Jeonghyeon

Jiashang EfåÌ

Jin Dynasty

Jinpyo

Jlri Mountain

PUGGION1.The Yogacara-Faximg

Later Goguryeo

Later Baekje

Meditation Master Hongli

Misu

Namwol Mountain

Nohil Budeuk

Northern Gyeongsang

Northern Qi

Pancayogabhumi

Penitence Bureau

Pukuang

Samatha

Sanjiejiao

Shandao Sanzang

Shelun

Silla

Sinbang

Sohyeon

Songnl Mountam

Sui Dynasty

Syeong Society

Taehyeon

Taiyuan

Tang

Tanqian

Ten Stages of the Bodhisattva

Tlanbao

Tiantai

Vol

Tongzi si

Uicheon

Vlpasyana

Wanshou SI

Wu Ze-tian

Wujie

Won-gwang

Woncham

Woncheuk

Wonhyo

Wonju

Xinxing

Xuanzang

Yi Ja-gyeom

Yl Ja-ul

Yonghwasa Yongjangsa

Yukpngeon

Yuan

Thiyi