The laity practice

The laity practice (1) (definition, maturity, behaviors)

What does the practice lie in?

In the context of dhamma, what we usually call "practice" is not an exercise or a ritual that ought to be performed at some particular times, but simply a training into a life style, a mode of existence, during which our mind gets little by little used to lessen its impurities, until a right knowledge of reality will be developed.

When we speak about Buddha, we consequently speak about "Buddhist practice". The one who adopts a life style that befits the dhamma teachings will therefore be a "Buddhist". It is advisable indeed to define this word.

Who is a Buddhist?

In no wise is a "Buddhist" the follower of a mystic ritual or some marginal movement that lives apart from the rest of the society, which requires a conversion.

Even though, nowadays, many persons who claim to be Buddhists have life styles and embrace customs that drastically go astray from all that which originally defined this term, the "Buddhist" is only a person who lives in harmony with the teachings of dhamma.

If our father is named Peter, if he gives us advice's and if we put these advice's into practice, at this moment we shall be "Peterist".

Also, we shall be "Jenniferist" when we shall follow the advice's of our mother Jennifer.

In the same way, a "Buddhist" is no one else than the one who puts into practices a life style that is in harmony with Buddha's teaching.

It is not about a practice that we integrate from time to time into our daily lives, which we integrate when we have a bit of "spare time" to be spent for it.

It is not even a kind of activity that would take part into our leisure activities, in the same way as ballet dance or archery might do.

That is our whole life, indeed, up to the most insignificant details of our daily lives, which we take as stand points of our practice. So, "Buddhist" practice essentially lies in a way of life that one puts into practice or than one instead tries to put into practice, because this training is after all a permanent attempt.

We try every day, every moment, according to the effort that we want indeed to put into it, to perfect this training in line with life, by striving to reduce and to avoid what is impure, unhealthy, useless and unfavourable, and by keeping on developing and maintaining what is pure, healthy, useful and beneficial.

Therefore it is equally absurd to assert: "I am a Buddhist but I am not a practising Buddhism" as to claim: "I am a vegetarian, but I eat meat".

The laymen

The laymen and the others

From the point of view of dhamma, there are two categories of persons: Those who adhere to dhamma, that is to say those who rely on Buddha's teaching; and those who do not adhere to dhamma.

Among those that do not adhere to dhamma, whether we deal with followers of a religion or not, whether we deal with followers of a school of thought or not, one finds all the persons who adopt one or several beliefs among the group of those that exist apart from dhamma.

As an example, the simple fact to think that nothing does remain whatsoever after death, is a kind of belief in the same way as any other is.

In this group, we find monks and nuns, who totally dedicate themselves to the practice suggested by their respective doctrines so as to reach the goal that these one assert.

We find hermits, who isolate themselves in remote places to observe an ascetic mode of existence. They do it so as to reach the purpose that is supposed to get training proposed by their own faith. Those do not belong to any religious school.

We find "priests" and "priestesses", who are relatively involved into the suggested or imposed practice by the teachings in connection with their faith, and who organize or direct the practice of the laymen.

Finally, we find laymen, who, according to the individual cases, adhere to a religion, to a school of thought (philosophy, sect, etc.) or only to their own ideas.

In the first two cases, they do it by devoting themselves to religious or ritual practices, ceremonies, recitations, prayers, considerations,philosophic debates, or by being self-contented with beliefs in ideas expounded by a monk, a guru, a philosopher, a book or any another support.

In the last case (layman adhering to his own ideas), he shapes his own way to be followed, according to the faiths, or he believes that what does occur after the death is the same thing for all, whatever are the actions being performed prior to it (Examples:

Rebirths do occur in a totally unpredictable way; everybody is reborn in a realm of paradise or blissful celestial world (or demoniac); everybody reaches the stage of the divinity; before and after life, only nothingness does prevail, as soon as one dies, nothing whatsoever does remain; etc.)

This type of belief is one of the most wide-spread, it explains why so many persons live so selfishly by enjoying pleasant things, which they get access to, to the full, by radically running away from all that which seems to be unpleasant, devoid of pleasure or boring.

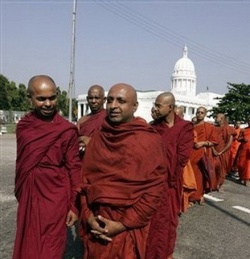

Among those who adhere to dhamma, there are bhikkhus, whom we often call the "Buddhist monks". They fully devote all their time to the practice, to the realization, to the study and to the dhamma teachings.

There were bhikkhunīs, "Buddhist nuns", who did exactly the same thing, but their community disappeared since the 10th century, at the same time as sikkhamānas, who were women of intermediate status between sāmaṇerīs and bhikkhunīs, also did.

They were in period of training, intending to become bhikkhunīs.

There are sāmaṇeras, whom we call "novices" or the "little monks". They learn monastic life, they dress in the monks' robe, but their discipline is sharply more flexible than those of the bhikkhu. To become bhikkhu, they have to wait to reach twenty years of age.

There were sāmaṇerīs, feminine version of sāmaṇera, whose presence vanished since the end of the feminine monastic community.

There are those whom we call the "nuns", who are women who opt for a monastic or semi-monastic existence.

They do have a little particular status, halfway between the one of the bhikkhu and the one of the laity. besides certain rules, they have to observe eight rules.

Their life is dedicated to the dhamma, even though they perform many activities specific to the laity. Who is a lay person?

Finally, among the people who adhere to the dhamma, all those who are not bhikkhus, or sāmaṇeras, or nuns are laity. We can divide lay people into three categories:

They like to claim that they are Buddhists, but do little else than run after pleasures and engage in business activities; if they observe one or two precepts, it is only because it is easy for them; they don't want to dedicate any effort to the rest.

Even though they claim to be inclined to meditation, they convince themselves that they never have any time to practice it.

- There are also lay people who try to dedicate more time and effort to follow a way suitable to the development of knowledge (of reality).

They more or less observe the five precepts (sometimes the eight), they like everything that concerns the dhamma aesthetically (monuments, statues, ceremonies), they readily spend time reciting texts dealing with Buddha's teaching, watching the quality of their actions, regularly making donations, attending meditation sessions, and sometimes, taking ordination for a short period.

- Finally, there are laity who, within their possibilities, try their best to progress quickly and effectively on the path to the cessation of suffering.

These ones very regularly train in being generous, in being vigilant and in applying full mindfulness. Their observance of the five precepts, if not eight, is scrupulous.

Some of them even intend to lead a monastic life permanently.

Although they all point to a sole aim, the objectives of Buddha's teaching are very diverse. They consist, among others, in:

- Inducing the first category of laity to improve their way of life so as to become laity of the second category.

- Encouraging the laity of the second category to maintain the positive aspects of their way of life and inciting them to improve on this so as to become laity of the third category.

- Encouraging the laity of the third category to maintain the positive aspects of their way of life and suggesting them the experience of complete renunciation (monastic life).

The pāramīs

In a prison cell lived four men. The first was ignorant and lazy, the second was ignorant and hard working, the third was skilful and lazy, and the fourth was skilful and hard working. Each had the possibility to work and earn a little money.

The lazy ignoramus had a thoroughly miserable existence; he did nothing at all during the day, was terribly bored and never obtained anything more than the bare minimum for his subsistence.

The hard-working ignoramus enjoyed a more comfortable life, because his work allowed him extra food and small treats such as a bottle of wine or magazines.

The skilful lazy person did not have a very pleasant existence.

As he did not put any effort in his work, he did not earn the money needed to buy things that would have allowed him to enjoy a better quality of life. However, knowing how to think, he suffered less than the lazy ignoramus, because he knew how to manage his condition better.

Thus, he succeeded more easily in being satisfied with little. However, his incorrigible laziness eventually prevented him from thinking properly.

The skilful worker was competent in his work. Knowing how to think properly, he knew how to manage his money wisely.

He learnt to content himself with little to save most of the money he earned. He had nothing good to drink or eat, or pleasant readings to offer himself.

Nevertheless, after a while, having endured the necessary time, he was able to pay off the bail to get out of prison.

To make the analogy of this story, we can say that:

The prison represents the continual dissatisfaction of existence (dukkha), with its "ups and downs", the cycle of rebirths (saṃsarā).

- Ignorance represents ignorance.

- Skill represents wisdom.

- Laziness represents the lack of motivation to cultivate wholesome actions.

- Work represents effort (the effort to develop and maintain what is beneficial, the effort to practice properly).

- The money represents the consequence of positive actions, merit (kusala).

- The release represents liberation (from any form of dissatisfaction).

Conclusion: To develop merit, it is necessary to perform positive actions, to make efforts of generosity, honesty and concentration.

Nevertheless, if this is done with ignorance, merit will be badly used and, so to speak, "wasted". Thus, it remains profitless. For this merit to be beneficial, it must be cultivated with wisdom, that is, positive actions should be performed with the intention to take care of and develop the dhamma (for one's own progress and that of others).

Comment: More than positive actions, the more profitable actions are simply abstinences from destructive or worthless actions.

This explains why it is essential to understand clearly the actions that we perform and know how we have to carry them out if we wish them to be really profitable.

The prison story also shows us that wisdom is useless without effort, which is indispensable for the development of wisdom. Thus, only the development of pāramīs does allow us to progress on the path to liberation, at whatever level one may be.

If someone benefits from all the elements which allow him (her) to make of his (her) existence a training in the dhamma (birth as human being, in a favorable environment, in a place and time when the teaching of a Buddha (sāsana) is accessible, understanding the value of such a training, urge to embark in it, lack of serious obstacles such as a poor health, etc.), this means that he (she) has already developed numerous pāramīs in the past.

If, besides these conditions, someone devotes himself (herself) with ease to "meditation" (training into satipaṭṭhāna), it means that he (she) has developed even more pāramīs.

If a person opts for the life of renunciation by joining, in a most natural way, the monastic community (saṃgha), it means that even more pāramīs have been developed. Finally, when our pāramīs reach complete maturity, we cannot but experience nibbāna, the cessation of all suffering.

The ten pāramīs

Buddha gave us a list of the ten pāramīs:

- dāna pāramī: Abandonment of possessions (animals or non-living objects) by making donations.

- sīla pāramī: Control of actions and speech to avoid unwholesome actions.

- nekkhamma pāramī: Renunciation of the lay life in favor of the solitary life (bhikkhu, hermit).

- pañña pāramī: Development of knowledge and understanding through study and analytical reflection. To teach knowledge to others. To use one's wisdom for a maximum of benefits.

- viriya pāramī: Effort to work as much as possible for the good of others, even at the risk of one's life.

- khantī pāramī: Establishment of an always perfect tolerance, irrespective of the actions and words of others towards oneself.

- saccā pāramī: Truthfulness (to say only what is right).

- adhiṭṭhāna pāramī: Decision to devote oneself to beneficial actions and to remain steadfast on it.

- mettā pāramī: Maintaining a state of mind turned to the happiness of others, to practise love for all beings without exception.

- pekkhā pāramī: Rejection of hatred and worship. Not to follow any particular idea. Maintaining the mind in equanimity.

Love and benevolence

Towards whom to develop love?

If we wish to progress on the path, it is essential to develop mettā. The love in question is an unlimited love that encompasses all beings, whatever they are.

As we can read in the mettā sutta (discourse on loving kindness), it consists of developing mettā towards all beings, humans as well as animals, those we know as well as those we do not know, those we see as well as those we do not see, those that are pleasant as well as those that are hostile, those that are close as well as those that are far, those that are small as well as those that are big, etc.

Naturally, one does not need a lot of effort to practice mettā, benevolence and tolerance, towards those who are dear to him (her).

However, when the question arises as to apply it towards those who cause us trouble, those who act badly towards us, those who commit only hateful and unwholesome actions, it becomes more difficult.

It is precisely this difficulty that gives us the opportunity to progress on the path of wisdom. It is exactly the same with meditation:

When everything is well, when everything is comfortable, when there is no pain, no itch, when it is not too warm or too cold and when silence is total, we feel well, assured, but we shall have no opportunity to progress correctly. How to practice mettā and benevolence?

As with anything in the dhamma, we could begin to develop mettā, benevolence and tolerance, gradually.

For this, it is simply sufficient to get used to cultivate, from time to time, a state of benevolence towards one or several beings, to strive to send mettā mentally to someone who behaves badly towards us, to tolerate as far as possible an action that displeases us, whether committed voluntarily or not.

Or still, we suppress those prejudices that we could easily have when seeing someone having a bizarre attitude, and pay attention for a few moments, to notice possibly that this person is anguished, ill-at-ease, and apparently leading a painful existence.

At that time, it will be natural to develop feelings of compassion and benevolence towards this person.

If he (she) is sensitive and if he meets our glance, he (she) will see immediately that we show him sincere affection, he (she) will be able to feel less rejected and benefit from a positive mood.

If there is a chance, we could even engage in a conversation with him (her), talking about simple things which may eventually be linked with him (her), and which could be a precious help to him (her).

For a generalized practice of mettā and benevolence, we begin for example with our close relations, the members of our family and our friends, then we gradually expand, including at first our neighbors, our work colleagues, our companions in study, sports or any group. We then add all the beings that we meet.

For example, when on a bus, we can occasionally spend a short while to develop thoughts of benevolence towards all those who are in the vehicle.

We continue by including all the beings in the village, district or city, without forgetting the mosquitoes that sting us! Then, all the beings of the country, and finally, those on the planet and the whole universe.

To develop the pāramīs , many of us who do not feel able to follow a training into concentration, such as the application of attention to physical and mental perceptions (satipaṭṭhāna), could more or less regularly devote time to the practice of mettā and benevolence by means of prayer.

To do this, we recite a sutta dealing with mettā , benevolence and compassion.

While reciting them, we close the eyes and concentrate on the words we pronounce.

Such a sutta recited in a group, can provide support not only to develop mettā, benevolence or compassion more easily and more enduringly, but also some concentration that will be greatly beneficial for the cultivation of the pāramīs.

Naturally, for this to be effective, these prayers must be recited with an understanding of what is said, or at least with an idea of what the texts in question say (otherwise the value is lesser), and to concentrate on this, avoiding to let the mind wander somewhere else.

It is important to do this wholeheartedly.

If we want this practice to bear fruit, it is necessary also to try to preserve the same state of mind at the beginning and after the prayers. Similarly, one must try to remain tranquil for at least a few moments before the prayers, in order to have the mind well attuned.

Ideally one should keep this state of mind at all times, so that the time of prayer is only a focusing permitting to maintain an almost permanent state of benevolence.

One's relations to others

Buddha showed to us how to reach the definitive cessation of any form of dissatisfaction. Before reaching it, the path is long, it requires for each of us to perfect at all levels, beginning from the base, otherwise how could we build anything on impure bases?

Let us feel reassured, the Buddha does not forget anybody; he explains, giving invaluable details, how every person has to act if he/she wishes to benefit from an existence that is as profitable as possible for oneself and for others, regardless of the social milieu and position in society.

He explains, among other things, how to manage a business or how a king (or a head of state) should act towards his people, and all, quite naturally, with the aim of establishing an ideal for all in terms of human relations and mutual respect, and, consequently, to offer everyone a framework suitable for training in the dhamma.

Thus, below, the duties of one to others according to the Buddha, for anyone wishing to lead his life in the most noble and the most profitable way, that of the dhamma.

Comment: Cultural customs are very different from one country to another and from one time to the other. It is necessary in certain cases, to know how to adapt in consequence.

The duties of a child to his (her) parents

1. To nourish them when they are not longer able to provide for their own needs because of their age. 2. To take care of their administrative procedures. 3. To continue the good practices of the family like honesty, generosity etc. 4. To be worthy to receive their material and spiritual heritage. 5. To perform ceremonies after their death.

The duties of a parent to his (her) children

1. To accustom them from very small to a good moral conduct. 2. To teach them good social manners (respect for others). 3. To transmit them knowledge and a harmless profession. 4. To marry them to a partner of good moral conduct who is suitable for them. 5. To bequeath them their inheritance when the time comes.

The duties of the pupil to his (her) teacher

1. To get up in sign of respect and go to receive him (her) when he (she) arrives. 2. To render him (her) a service if necessary. 3. To be eager to listen to his (her) advice. 4. If living with him (her), to help him (her) with the daily chores. 5. To try hard to learn what one does not yet know and not to forget what one has already learnt.

The duties of the teacher to his (her) pupil

1. To instruct him (her) well in matters concerning social life, customs and manners, as well as in the spiritual field. 2. To make sure that he (she) retains well what one teaches by making him repeat several times in the day. 3. To teach everything one knows without concealing anything. 4. To introduce him (her) to one's friends and associates so that he (she) can obtain a job. 5. To guarantee his (her) material and spiritual safety (recitation of protective texts).

The duties of the husband to his wife

1. To be respectful to her and not to address her with vulgar words.

2. Not to disdain her.

3. To be faithful.

4. To give her the housekeeping money and allow her free management of it.

5. To buy her beautiful clothes and jewellery.

The duties of the wife to her husband

1. To be prudent and to dedicate herself entirely to the care of the household. 2. Know how to receive his friends and members of his family. 3. To be faithful. 4. To administer suitably the property and finances. 5. To be skilled in all household duties (cookery, sewing, ironing, etc.)

The duties of a young man to his friends

1. To be generous and open-hearted.

2. To speak politely.

3. To be ready to render service.

4. To avoid putting himself above others and to give the same chances to everybody.

5. To be honest.

The duties of friends to young men

1. To protect their health when they are unconscious (drunk, doped).

2. To protect their possessions when they are unconscious (drunk, doped).

3. To protect them from imminent dangers.

4. Not to abandon them when they have troubles.

5. To take care with benevolence of their children (giving them employment or other services).

The duties of an employee to his (her) employer

1. To get up before him (her).

2. To go to bed after him (her).

3. To take only what is given.

4. To take one's duties seriously.

5. Not to speak badly of him (her), to speak well of him (her).

The duties of an employer to his (her) employees

1. To give them work according with their capacity. 2. To give them food and a salary. 3. To take care of them in case of illness. 4. To share with them the good food or drink when available. 5. To grant them proper leave.

The duties of a lay person to a monk

1. To perform actions motivated by loving kindness.

2. To say words motivated by loving kindness.

3. To have thoughts of loving kindness.

4. To invite him to visit one's house if necessary and to invite him to report his needs.

5. To provide him with the four requisites: lodging, clothing, food and medicines, within the limitations of one's means.

The duties of a monk to a lay person

1. To teach in order to avoid what is unwholesome (cause of suffering for oneself and others).

2. To encourage him (her) in what is wholesome (source of happiness) like generosity, virtue and meditation.

3. To generate loving kindness towards him (her).

4. To teach what he does not know.

5. To repeat what he already knows.

6. To show the way to a more comfortable rebirth (deva world) or towards nibbāna.