Lineages and Structure in Tibetan Buddhist Painting: Principles and Practice of an Ancient Sacred Choreography

Abstract: Though compositional structure – which here means specifically the placement of divine figures – is an essential aspect of Tibetan painting, this theme has rarely been discussed or described by scholars. The conventions for depicting lineages of teachers in particular must be carefully taken into account when documenting thang ka that contain lineages with inscriptions. The historian should carry out, if possible: (1) decipherment of inscriptions, recording names; (2) historical identification of individual masters, furnishing dates if known; (3A) identification of the lineage, and (3B) listing its members in chronological order (i.e., following the sequence of lineal descent); (4) diagramming the position of all figures, following the numbering of step three. The present article classifies and describes the lineage structures found in the vast majority of paintings with lineages. Understanding lineage structure through these four steps allows the historian to identify the religious teacher and approximate generation of the patron who commissioned the painting, essential steps toward restoring the painting to its lost historical context.

Introduction

Although to the uninitiated, Tibetan Buddhist paintings may seem to be a chaotic and inexhaustibly variable universe, in fact their iconography is limited, orderly, and, above all, hierarchic. To fathom this art, one of the first steps is to recognize the hierarchic arrangements in which its sacred figures have been placed. For understanding the main conventions of precedence and hierarchy, moreover, one must learn to interpret in detail the depictions of guru lineages. Besides their intrinsic religious, iconographic, and aesthetic interest, depictions of lama lineages can furnish some of the few reliable historical clues for dating a Tibetan painting, which is already reason enough to study them. Yet despite their importance for a sound understanding of Tibetan art, the basic conventions of lineage portrayal – “hierophantic choreography” – and other compositional elements in tangka paintings have rarely been discussed or described in detail.

Lineage structures are not self-evident. Several linguistic or historical hurdles must be cleared if one wants to document them in a satisfactory way:

- Correct decipherment of inscriptions recording names

- Correct historical identification of individual masters, furnishing dates if known

- (A) Correct identification of the lineage, and (B) listing its members in chronological order (i.e., following the sequence of lineal descent)

- Diagramming the position of all figures, following the numbering of step 3

The first Tibetologist to study in any detail tangka depicting lineage gurus was G. Tucci, who in his scholarly tour de force Tibetan Painted Scrolls[1] described three tangka that each portrayed as main figures four lineage masters of the Ngorpa subschool of Sakyapa Path with Its Fruit (lamdré) instructions. Tucci succeeded in (1) deciphering the inscriptions and (3A) identifying the main lineage. He also (3B) correctly ordered the main figures within each tangka, though not as a continuous series within the main lineage.[2]

In the five decades that have followed, most catalogs of Tibetan artworks did not reach the level of Tucci’s work in their analyses of inscribed lineages, though in the 1970s a few scholars began to perform at least step 1 of the documentation. Anne Chayet in two entries of a major exhibition catalog[3] documented the names of two lineages. For painting no. 122, she presented the names of lineage masters in their correct order (step 3B). Though she did not attempt steps 2, 3A or 4, she demonstrated implicitly an understanding of structure.[4]

Another book of the 1970s to furnish names from inscriptions was a sales catalog of paintings from Ngor Monastery published from Paris in 1978 by the Galerie Robert Burawoy.[5] This book, of unusually large format and price, documented the names of lineage masters in several paintings, presenting them in white letters on transparent pages overlaying the color plates. Otherwise the catalog avoided numbers for plates and pages, and it did not sequentially list, date or otherwise identify the lineage masters.[6]

In several catalogs of the 1980s and 1990s, collaborators transcribed some of the inscriptions bearing the names of masters.[7] But they listed and diagramed the names of lineage masters in an ad hoc order, not following the sequence of the lineage. The catalog of Essen and Thingo 1989 deserves praise for presenting all available inscriptions, but even its lists and diagrams were not in conformity with the order of the lineages portrayed.

Since the early or mid 1990s, several other scholars noticed the potential usefulness of lineage analysis for dating.[8] In recent major catalogs the documentation of some entries is also becoming better.[9] To encourage this trend I would like in the present article to share some of the internal rules and outer expressions of structure that I have encountered in my own research.[10]

Previous Research on Principles of Composition

Like lineage analysis, the general principles according to which Buddhas and other sacred figures are placed in a Tibetan painting have received relatively little attention until now. Again we owe the first steps to G. Tucci, who in Tibetan Painted Scrolls devoted chapter thirteen to “The Plan of the Tankas,” where he described many key iconographic and decorative elements.[11] He had little to say about composition; besides that, the tangka followed a similar general plan, with many shared compositional “characters,” and the main figure (tsowo) dominated the central space, representing the essence of the painting.

K. M. Gerasimova in her 1978 article “Compositional Structure in Tibetan Iconography” stressed the role of the iconometry of individual figures, but she underestimated the complexity of other elements of structure in iconic (or “representational”) paintings:

- The construction of individual figures and decorative-ornamental combinations on a flat surface actually exhausted the entire problem of the organization of space in the representational icon. Its compositional formula consisted in the quantitative establishment of the centre and a symmetrical grouping of the secondary components according to a principle of simple transfer.[12]

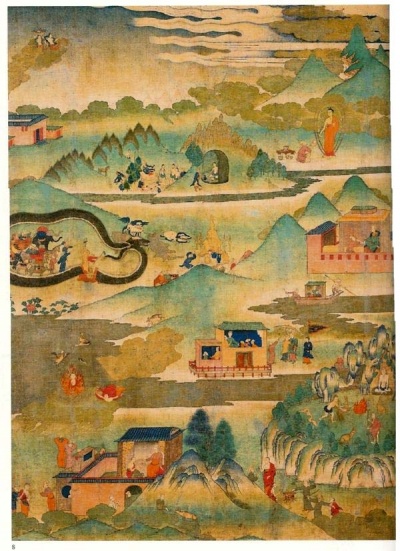

Gerasimova[13] described much more complexity in the structures of biographical or narrative paintings. In reality, even for the usual iconic depictions of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, the subject of composition is more complicated than admitted by either Tucci or Gerasimova. But not hopelessly so.

A Grammatical Comparison

The non-verbal signs of a Tibetan scroll painting or tangka can be read and interpreted almost as one would read a written text. A painting of this tradition has its rules of “grammar,” so to speak, which allow one to interpret its arrangements systematically. As in many written languages, one can distinguish in a painting several levels of description, such as those corresponding to letters, words, and sentences. To follow the analogy of language and reading, the sacred figures in a tangka could be considered to be like the words in a language. The individual attributes of a figure – i.e., iconographic elements such as colors, hand gestures, dress, and ornamentation – are like the letters of the words. To determine the correct ordering of the figures, there exist rules governing composition – something like rules of syntax.

Two Main Means for Establishing Structure

The “syntax” of a Tibetan tangka is not self-evident and will only be recognized by someone who can identify and classify the individual figures. But how to identify the figures? The two main means are: iconography and inscriptions.

The first means, iconography, is adequate for identifying to which class a figure belongs. But it is not very reliable for identifying individuals within the most important class, namely gurus and lama, because their iconography was sometimes fluid. The same master or adept (druptop) may be shown in different postures depending on different contexts (for example, the four forms of Virūpa corresponding to four famous episodes of his life) or according to different painting traditions. Nevertheless, iconographic factors, such as the dress, hair or hats of the lama, can be enough for a provisional first identification of a group of figures and possibly of a few more famous individuals.

Still, doubts often remain, especially for paintings from less common traditions. Here written evidence such as inscriptions are sometimes the only means for a firm identification. Indeed, at the present early stage of research, Tibetan art historians should concentrate as much as possible on paintings with readable inscriptions. Lineages, moreover, should be analyzed with caution and sophistication, not simplistically or uncritically, especially where the main figure and the last two or three historical figures of a painted lineage cannot be identified.

Traditional Tibetan Classifications of Buddhist Art

Tibetan painters and learned religious masters were aware of the basic hierarchical rules and chronological conventions expressed in paintings.[14] Such rules were important aspects of the complex and highly developed tradition of religious art that they maintained. In traditional Tibet, art was mostly religious, and according to Tibetan “iconological” theories recorded in treatises on sacred art (zorik tenchö), art works were traditionally classified into three main types, each corresponding to an aspect of Buddhahood: enlightened body, speech, or mind. Thus the main types of sacred objects, in ascending order, are the three support (ten):

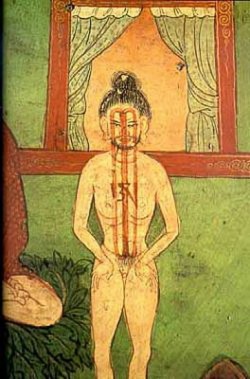

bodily support can be further divided according to their spatial extension into two classes: (1) painted (dri), i.e., two-dimensional, objects, and (2) sculpted or otherwise outwardly extending (bur), i.e., three-dimensional objects. Here we will be concerned exclusively with bodily support of the first type: painted artwork (driku), especially with painted scrolls (tangka; tangku; kutang).

Classification According to Function

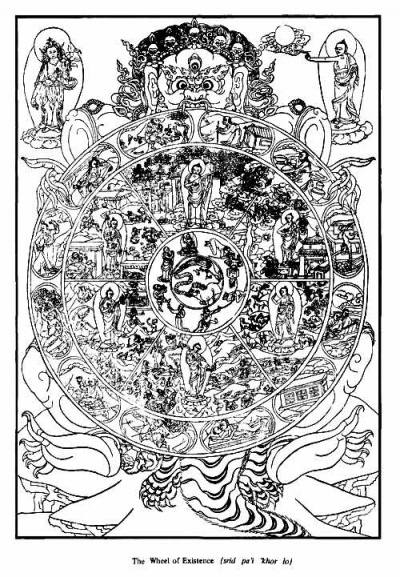

Painted images can furthermore be classified according to their main function, though this is not a traditional Tibetan classification:

- Simple “bodily support,” which are plain iconic representations of a divine figure

- Narrative paintings, which place the figures within a historical or legendary story, such as a saint’s life

- Didactic paintings, which symbolically represent religious truths

- Astrological diagrams, which are meant to bring luck and repel bad fortune

- Representations of offerings, especially offerings made to protective deities in order to gratify and placate them

Paintings with guru lineages made up just a small portion of the first class, though that proportion was much higher in the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries. Thus by no means is it the case that all tangka depicted lineages, and complete portrayals become increasingly rare in recent centuries.

Stylistic Trends

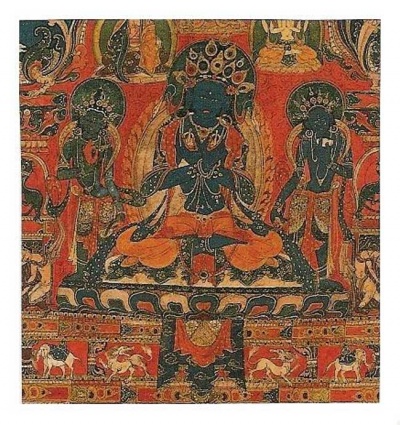

When one examines a number of dateable paintings from the twelfth through nineteenth centuries, one notices tremendous changes in style. Basically, the styles evolve from older Indian styles into later, more Chinese-influenced ones. This is almost to be expected, given the geographical location of Tibet between the two great civilizations of Asia – India and China – and the fact that Tibet received its original Buddhist impulses mainly from India.

Though this stylistic evolution affected the depictions of the bodies and clothes of divine figures less markedly, its effect on the backgrounds and other decorative details can hardly be overlooked. Among other things, the styles evolve from a mainly red, yellow and orange color scheme, with abstract decorative designs in the background, to a primarily green and blue palette, with more or less stereotyped elements of Chinese-style landscapes in the background.

Concerning the basic conventions of figure positioning, the arrangement changed over time from a strictly linear arrangement in straight rows and columns to a somewhat more staggered and natural arrangement of figures in a landscape. The earliest convention is clearly Indian, while the later developments (right-left alternation beginning at top-center) no doubt reflect a penetration of Chinese traditions. These changes jump out at the historian today thanks to twelve centuries of hindsight, but in fact Tibetan Buddhist painting remained deeply conservative and changed at a very slow pace throughout most of its history.

Principles Determining the Size and Placement of Figures in a Painting

Since Tibetan Buddhist art was and remains a conservative, formal, and orderly world, in which nothing of significance can occur by chance, what were the organizing principles that determined its pictorial compositions? Here by “composition” I do not mean the layout of such secondary, decorative elements as landscape, but specifically the choice and positioning of figures. The main organizing or “syntactic” rules of composition are not complicated, and they can be summed up in terms of three expressions of precedence or hierarchy:

- A figure’s status as a “main” or “minor” figure

- To which iconographic class the figure belongs within the levels established by 1

- Which special rank, if any, an individual figure has within the iconographic classes established by 2

The Hierarchy of Main and Minor Figures: Distinguishing Levels of Priority

The first essential distinction of hierarchy is simply the determination of which figures are of main importance and which are of lesser importance. Most paintings contain at least the two levels:

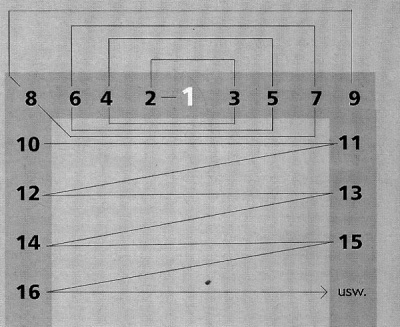

Here for the sake of simplicity I have limited the minor figures to just one level (II). Some tangka paintings possess two or even more levels of lesser figures, i.e., (III), (IV), and so forth.

A deity becomes a “main figure” or “minor figure” in a given painting according to the immediate spiritual wishes or priorities of the devotee or patron commissioning the work. (For a lay person, these priorities would have been established through the advice of a religious preceptor, who might even sketch on paper a simple plan of a painting showing the position of each deity by writing its name where it should stand.) To put it another way, a figure is chosen as the “main figure” (or group of main figures) of a painting simply by being of immediate importance, for one reason or another, to the patron. For example, a deity such as White Tārā is often chosen as the main figure to ward off serious illness or other threats to the patron’s longevity.

One can immediately recognize and distinguish the members of priority-levels I and II through differences of size and placement. A main figure is always larger, while minor figures are smaller. Furthermore, a single main figure is usually positioned in the middle of the painting on the central vertical axis.

A central figure can also be positioned to the right or left of the center axis (tsangtik), such as in some Chinese-influenced series of arhats or portraits of masters, where the main figure sits in partial profile on a wooden throne or platform within a landscape. This off-center positioning confused Tucci, who sought a doctrinal or iconographical explanation for it and the “missing” lotus seat, beyond a mere change in aesthetic preference.[15] The solution is easy to see when one takes into account the entire set of paintings. The central axis still exists: it is the vertical axis of the main painting in the middle, toward which all the main figures in the tangka to the right and left turn their faces. Moreover, the central vertical axis of each lateral painting remains the aesthetic central axis around which balance is achieved in that composition, and the main figure of that painting turns his face toward it, too.

An artist has to establish for a painting or set of paintings relatively larger or smaller units of measures for each priority-level. The sizes of the faces (zheltsé) or of the palms of the hands (these are classical units of measure, each made up of twelve finger-widths or sormo) are much larger for a main figure than for the minor ones.

In theory, all figures can belong to the priority-level of the main figure (I), and a painting can have no minor figures. But in actual practice this rarely occurs for paintings having more than two or three figures. In most paintings, a main figure (or group of main figures) supplies both a spiritual center of gravity and a welcome aesthetic focus.

Hierarchy of Iconographic Classes within Each Priority-Level

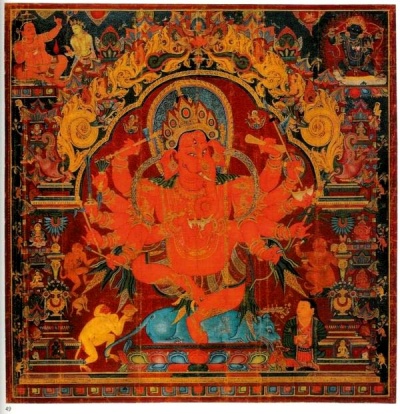

In contrast to the first distinction of main versus minor figures, which in some ways is based on personal, almost arbitrary factors, the second main distinction has to do with a more absolutely and permanently established hierarchy: namely, the ordering of the different iconographic classes of deities within the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon. The sacred figures of the pantheon each belong, in fact, to one or another relatively higher or lower class. The main classes of sacred figures include, in descending hierarchical order:

- Masters of the lineage

- tantric deities (Yidam)

- Buddhas in sambhogakāya and nirmāṇakāya forms

- Bodhisattvas

- Goddesses (i.e., female bodhisattvas)

- Pratyekabuddhas; śrāvakas/sthaviras

- dāka and ḍākiṇī (Tib. khandro and khandroma), i.e., beings of high realization associated with tantric practice

- Wrathful protectors of the Dharma (dharmapāla), e.g., Vajrapāṇi or Mahākāla

- yakṣa deities (Tib. nöjin), e.g., the four great kings, guardians of the directions

- wealth-bestowing deities (norlha), e.g. Jambhala

- Other lesser deities (mahānāga, terdak, etc.)

This list embodies a spiritual hierarchy. The earlier classes embody higher realizations, while the subsequent ones embody relatively lower ones. For example, the realization of a perfectly enlightened Buddha is higher than that of a bodhisattva (who is, after all, still a candidate to Buddhahood), and of course it is higher than that of a worldly deity. The tradition does, however, distinguish between ordinary and great bodhisattvas; great bodhisattvas such as Avalokiteśvara are considered to have reached a Buddha-like level of realization, though they do not manifest themselves as a Nirmāṇakāya Buddha. Another important distinction is between those deities who have reached the level of a saint (pakpa) and those who are gods of the worldly sphere (jiktenpé lha).

The spiritual hierarchy of the above list is expressed ritually by the order in which such deities are invoked in the ceremonies of Tibetan monasteries. In consonance with Vajrayāna doctrine, the gurus take precedence over all else.

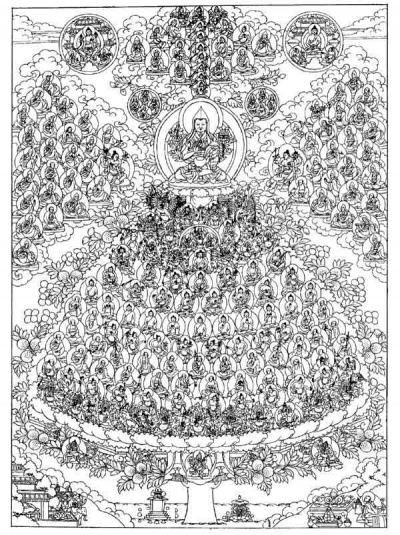

How is this hierarchy expressed in a painting? As before, it is shown through size and placement, though here with some differences. The hierarchy or spiritual precedence of one class over another is manifested, first of all, through its vertically higher placement in the painting, relative to the other classes of the same priority-level. A good exemplification of the hierarchy or classes is the so-called assembly-field (tsokzhing) type of painting.[16]

Secondly, a higher or lower status of a class is expressed through larger or smaller physical proportions (but here, again, relative to other classes on the same level of importance). There exists, in fact, an exact system of figural proportions by which higher ranking classes possess larger proportions than the ones beneath them.[17] The scale of measurements (i.e., the actual length of a “face-length” or “finger-width” unit), however, remains the same within one importance-level.

Usually there is only one main figure, and thus the division into classes only concerns the minor figures. But occasionally tangka contain two, three, or more “main figures.” In that case the rules of placement according to class hierarchy operate within that superior group, too.

Hierarchies within the Same Class of Sacred Figures

The third basic hierarchical distinction, that which influences the placement of figures within a single iconographic class on the same priority-level, does not actually pertain in every iconographic class. Sometimes all the figures within a class enjoy the same status, and their ordering within their class is somewhat arbitrary, though members of established groups are often depicted according to an established order, based, for instance, on the sequence of their appearance in a canonical text or famous older painting that functioned as model.

But when a true hierarchy does exist, it may reflect a doctrinal superiority or a spiritual seniority. The deities of the Anuttarayoga Tantras, for instance, are accorded a higher status over those of the Yoga Tantras and the two still lower classes of Tantra, in accordance with the doctrinal ranking of New Translation (sarmapa) Tantras. In the representation of a lineage of teaching masters, by contrast, the order expresses the precedence of relative seniority within that lineage: a spiritually senior figure takes precedence over a junior one. This does not necessarily mean seniority in age (though in fact a chronological succession of older to younger masters is the typical case). Here the decisive factor is spiritual seniority, which is established by one master being the religious teacher of the other.

Artistically, precedence may also be shown for figures on roughly the same vertical level by placing superior figures either closer to the center, or to the right hand of their inferiors. Thus, for a pair of masters both shown as main figures, the one to the right relative to the figures (i.e., to the viewer’s left) has the superior seat. Similarly, within a lineage or series, the position at the first figure’s right hand usually has precedence over that to his left, reflecting ancient Indian conventions for showing respect and, originally, customary uses of the respective hands for cleaner or dirtier tasks.

Special Exceptions Regarding the Guru

In a few paintings, the depictions of the patron’s personal guru or the great founding masters of his tradition have been pushed to a higher or more central position within their class (i.e., to a position indicating higher respect), motivated by special devotion to that master. Thus a single guru or a cluster of three founding masters may be moved to the top center, out of their expected spatial position according to normal linear sequence.[18] Sometimes the great founding masters have not only been taken out of their normal sequence and moved to a more central position, but they have also been depicted on a larger scale, i.e., on a higher importance level.[19] There also exists at least one painting where a figure of the guru has been elevated to a position within the highest priority-level, and in fact to a seat on the crown of the main figure, though this is extremely rare, and the guru is here portrayed with smaller proportions.[20]

Lineages and Structure

To summarize, the placement of figures is governed by hierarchic rules that operate within three contexts according to:

- The immediate spiritual importance of the figures for the patron,

- The iconographic classes within a given priority-level, and

- The relatively higher or lower position of the individual figure within a given iconographic class

Moreover, the same hierarchical principles apply both within a single painting and within a set consisting of numerous paintings. In the latter case, those principles determine the arrangement of the whole set.

But what does it mean, concretely, to say that the individual figures within an iconographic class are “positioned hierarchically”? There exist, indeed, a number of conventions to express positions of decreasing precedence in a Tibetan Buddhist painting, and in the course of history quite a few of them were actually employed. The modern scholar must make sure he or she has identified in each case which hierarchic conventions have been used. Here, a guru lineage in the painting can be an extremely helpful clue, since it often sets the pattern for the rest of the composition.

The Preeminent Position and Importance of Teachers

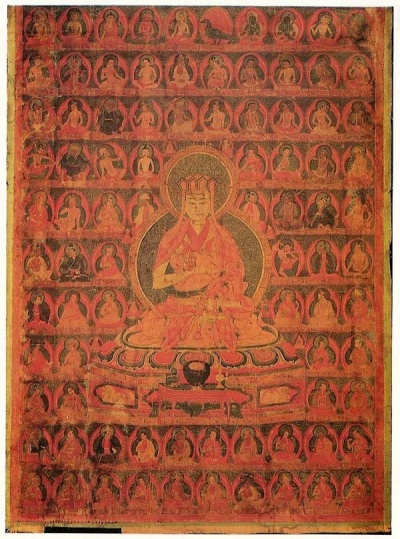

The masters of teaching lineages thus belong to the highest of all iconographic classes. Even when depicted as “minor figures” in relation to the immediate spiritual priorities of the patron, they still occupy spatially the highest positions in a painting. Their presence can therefore hardly be missed at the top, or at both the top and right and left side-columns, of many important old paintings.

Importance of Lineage Histories for Tibetan Buddhists

Throughout much of their history, Tibetan Buddhists have demonstrated a proclivity for depicting guru lineages. The resultant portrayals are of great importance not only as a record of a given lineage’s history and the iconographic representation of its masters, but also, when the lineage is complete, as very important clues for dating the paintings.

Tibetan Buddhists in other contexts of ritual and practice, too, carefully recorded and transmitted their teaching lineages to the extent they could. In the esoteric or Mantrayāna traditions of Mahāyāna Buddhism, such lineages were of crucial religious importance: the lineage gurus needed to be ritually invoked as a preparatory step in practice. This respect for the lines of gurus contributed to a deep and very concrete sense of history among many Tibetan Buddhist tantric masters – in contrast to the usual scholar-monks or geshé, whose main training consisted in the systematic study of non-tantric doctrine through memorization and debate and who were typically less textually and historically oriented.[21]

Because lineages were so important for Tibetan Buddhist practice, individual masters would write down the particular lineages for Tantric teachings that they had received from their various teachers. The resulting books often consisted of little more than bare lists of masters’ names and the titles of books or teachings, yet in Tibetan literature they made up a genre of writing called “teachings received” (topyik or töyik).[22] Artistically this same attention to lineages was expressed in the careful portrayals of many lineages of gurus. Painted lineages are an artistic expression of the same concern that also finds its expression ritually in the recitation of lineage prayers (gyüdep/ lamé gyüpala sölwa deppa).

Special Chronological Conventions for Lineages

As elsewhere in the planning of a painting, so too in the portrayal of lineages one usually finds an orderly and exact system at work. Indeed, painted lineages can be read chronologically, and thus interpreted as historical records. But for a correct interpretation one needs to determine in each case which particular convention of chronological descent has actually been used. For this, it is best to begin by:

- Identifying the starting point. Then it is much easier to follow the continuation of the lineage and thus determine

- The convention used for depicting the temporal sequence of the subsequent figures

Main Conventions Regarding the Starting Point

Lineages usually begin, as would be expected, with the earliest teacher. Thus they almost always begin with a Buddha, who, for the tantric traditions, is the tantric original-guru. This primordial teacher is Vajradhara for the New Translation Tibetan tantric schools, a blue-colored Buddha in sambhogakāya form holding a vajra and bell in his crossed hands, while for tantras of the Old Translation (nyingma) school, he is the original Buddha Samantabhadra. For non-tantric traditions, one can usually expect as the starting point the historical Buddha, Śākyamuni (in nirmāṇakāya form).

Where this first figure sits indicates the beginning of the lineage. There existed in fact several artistic conventions regarding the starting point of lineages, but the two most common starting points are:

- The top left corner (relative to the viewer, which is the top right corner, relative to the deities). This seems to be the oldest convention, and it is well suited to paintings where the figures are arranged in straight rows and columns.

- The top central position. This has become, since about the early 16th century, the most common convention, though it occurs in a few earlier paintings, too. It is suited to figures placed in a more realistic landscape (which at the top of the painting means in the sky).

Exceptions do exist, such as the special case where the first figure sits just to the left (relative to the viewer) of the top central position. Here another figure (the patron’s own guru) has for reasons of special respect usurped the top central position.[23]

Conventions of Descent

Let us turn now to some of the main conventions for portraying lineal descent. Once the beginning of the lineage has been located, it is normally not difficult to see how the lineage continues, whether straight across or down columns, or in an alternating fashion. There are several conventions for each starting point:

Descent Starting from the Top Left

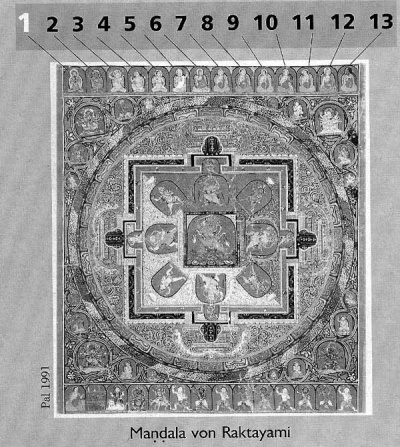

a. Straight across the top from left to right (for short lineages)

Among the various conventions of descent from the original Buddha Vajradhara at top left, one of the oldest and simplest is to proceed straight across the top row, from the viewer’s left to right.[24] This is well suited for lineages of up to about eleven or twelve figures, though in special circumstances it can be stretched to fifteen or even more.[25] The structure can be shown:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

b. Straight across the top from left to right, and the same once again in a second horizontal row placed beneath the first

When there are too many figures to be easily depicted in the first row, one solution (rarely used) is to add another row just below the first.[26]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | d1 | d2 | d3 | *14? | *15? | 16? | 17? |

An extreme example of this structure is found in a Bönpo tangka documented by S. G. Karmay in his excellent study, The Little Luminous Boy: The Oral Traditions from the Land of Zhangzhung Depicted on Two Tibetan Paintings,[27] where the series of eighty-six figures continues in this way in eleven consecutive horizontal rows of up to ten figures each, interrupted only by the larger central figure:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | ||

| 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | ||

| 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | ||||

| 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 57 | 58 | ||||

| etc. |

c. Straight across the top from left to right, and down one column

When the lineage consists of more than twelve or thirteen masters, another solution for the placement of excess figures is to run the continuation from the upper right corner down the right-hand column. A good example of this is the painting of Ngorchen Künga Zangpo (1382-1456) ordination lineage in the Zimmerman collection.[28]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | |||||||

| 18 | 17 | 19 | 10 | ||||

| 11 | |||||||

| 12 | |||||||

| 13 | |||||||

| 20 | 21 | 14 | |||||

| 15 | |||||||

| 16 |

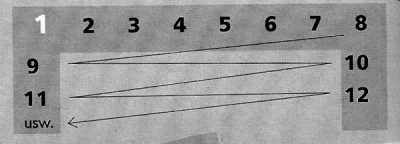

d. Straight across the top to the right, and then alternating

This is a variation on the same beginning, in which the top row begins on the far left and progresses to the right, before finally alternating between left and right columns. A good example is found in Rhie and Thurman.[29]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | ||||||

| 11 | 12 | ||||||

| 13 | 14 | ||||||

| 15 | etc. |

e. Left to right, interrupted in the middle

An interesting variation of the left-to-right sequence is found in certain old Taklungpa paintings in which the sequence has been interrupted in the middle by a centrally placed figure or figures representing the guru of the main figure or the three preceding gurus (founders of the tradition).[30] Here a single guru, figure no. 7 – Pakmo Drupa (1110-1170), shown with a heavier beard – has been moved to a central position over the main figure – no. 8, Taklung Tangpa (1142-1210). The lineage begins:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Another such case is found in Singer plate 41,[31] a painting probably dating to the last two decades of the life of its main subject, no. 11a, Sanggyé Wönpo (1251-1296). The composition here groups three important gurus – the three founding masters of Taklung – in the top center.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 11b | -s2- | -s3- | 7 | |||||

| 11a |

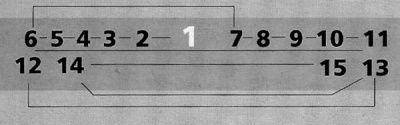

Descent Starting from the Top Center

a. From the center, across the top to the left and down the left side column, then back to the top center, from which then across to the top right, and down the right column

An example is the Mahākāla Pañjaranātha painting in Rhie and Thurman.[32] This painting’s lineage begins with Vajradhara at the top middle, progresses three figures to the viewer’s left, and then drops down the left column. Then it returns to figures no. 10 and no. 11, the first lay adherent and paṇḍita in the top row – Jetsün Drakpa Gyeltsen (1147-1216) and Sakya Pendita Künga Gyeltsen (1182-1251) – goes right, and finally descends down the right column. The structure is as follows:

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| 5 | 14 | |||||||

| 6 | 15 | |||||||

| 7 | 16 | |||||||

| 8 | 17 | |||||||

| 9 | 18 |

Note that the iconography of figure no. 10, Jetsün Drakpa Gyeltsen, actually corresponds to the usual later depictions of his father, Sachen Künga Nyingpo (1092-1158), who here should be in position 8. Could we here have Sachen Künga Nyingpo then in an anomalous position (10), owing to the great veneration paid him by the tradition? Or is Sachen Künga Nyingpo in position 8, and this is just a case of more fluid iconography?

b. From the center across to left, then across to right (and then alternating below)

An example is Rhie and Thurman no. 77.[33]

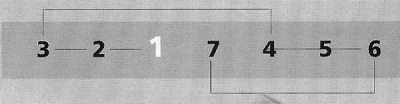

c. From the center across to left, across to right, then back to top center

In this painting the lineage jumps to the top center, before descending to figure no. 8, the main figure, Taklung Tangpa. Here the top center has been reserved for the guru of the founder.[34]

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

d. Alternating to the left and right, all the way down

This has been the most widespread convention since the sixteenth century, and it has practically replaced all other conventions.[35] A good example is Rhie and Thurman no. 64,[36] showing Paṇḍita Gayadhara (as master of the Path with Its Fruit) with surrounding lineage.[37] Here the sequence is: 1. top center, 2. his right, 3. his left, and so on. Thus the structure of the top row and the next few lines is:

| 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | |||||||

| 12 | 13 | |||||||

| 14 | 15 | |||||||

| 16 | etc. |

The above types cover probably ninety-nine percent of existing tangka. But they do not exhaust all possibilities. In fact, one should keep one’s eyes open for further variations expressing the same basic principles. Two recently analyzed tangka, for instance, were found to embody concentric structures:

e. Concentric, around a central deity

In this instance,[38] the lineage masters are arranged in semi-circles to the right and left of the central deity, Hevajra (H):

| 8 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 9 | ||||||

| 10 | 4 | H | 5 | 11 | ||||||

| 12 | 6 | 7 | 13 | |||||||

| 14 | 15 | |||||||||

| 16 | 17 | |||||||||

| 18 | 19 |

The last lama (19) is seven generations after Drogön Chögyel Pakpa Lodrö Gyeltsen (1235-1280), i.e., he brings the lineage down to about Ngorchen Künga Zangpo’s time (ca. mid-15th century). But the style seems to indicate a date a century or more later than Ngorchen Künga Zangpo (1382-1456).

f. Concentric, around a maṇḍala

The painting[39] embodies another concentric structure, but here the center is the maṇḍala of the deity Vajravidāraṇa:

| 12 | 1 | 13 | ||||||||

| 14 | 2 | 3 | 15 | |||||||

| 16 | 4 | 5 | 17 | |||||||

| 6 | 7 | |||||||||

| 8 | 9 | |||||||||

| 10 | 11 | |||||||||

| 18 | 19 | |||||||||

| 20 | 21 | |||||||||

| 22 | 23 | |||||||||

| 24 | 25 | |||||||||

| 26 | 27 | |||||||||

| 30 | 28 | 29 |

Figure no. 24 in the lineage is Ngorchen Künga Zangpo. Figure no. 30 is the final guru of the lineage, and not (as one might otherwise expect) the commissioning patron. He is the Ngor abbot Sanggyé Senggé (1504-1569). The final generations are:[40]

24. Ānanda (=ngorchen künga zangpo)

25. Kīrti (=gugé penchen drakpa gyeltsen)

26. (Lowo Khenchen Sönam Lhündrup [1456-1532]?) Lekpé Jungné

27. (Künga Sönam) Künga Sönam

28. Künga Lhündrup

29. Yeshé Gyeltsen

The tradition portrayed is Vajravidāraṇa in the tradition of Jayavarma and Jñānaśrī, with a 19-deity maṇḍala for its initiation.

Quirks and Complications

First impressions can deceive when interpreting lineages. To avoid error, one should try first of all to determine whether the painting depicts a complete lineage of masters or just a fraction.

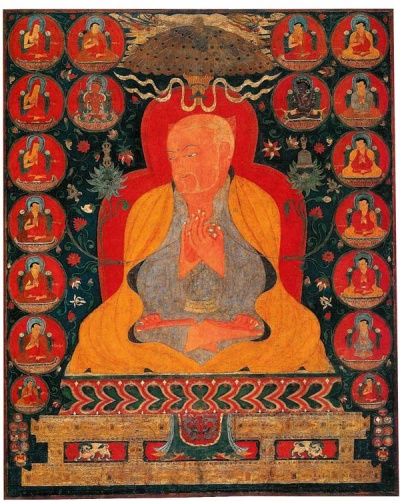

A Single Lineage Ending with the Main Figure

Most paintings end the lineage with the last minor figure. But in paintings portraying lama as main figures, a few compositions end the lineage by jumping from the last teacher pictured among the minor figures to the main, central figure. In this case, the main figure (or sometimes a pair of central figures) and the minor figures together represent a single complete lineage.[41]

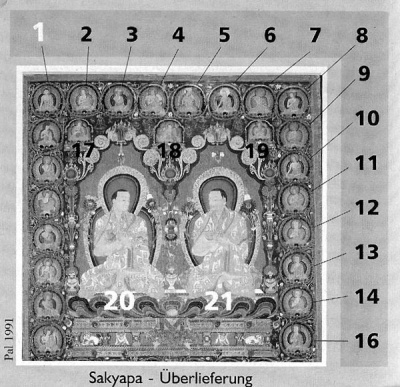

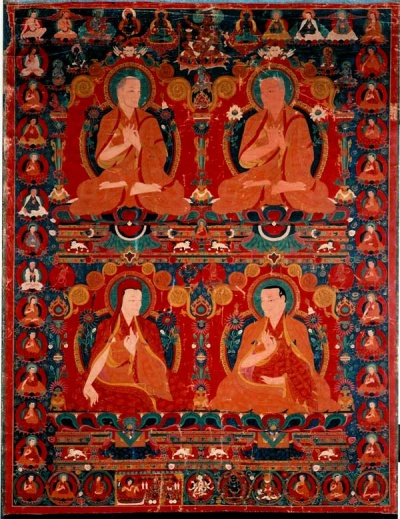

Combinations of Partial and Complete Lineages

Sometimes the same painting portrays a small fraction of one lineage (represented by a single main figure) and another complete lineage (represented by a series of smaller minor figures). Here the painting belongs to a multiple-tangka set, and the lineage of the main figure is continued by the several other paintings in the same set. It was also possible to depict a still larger part of an incomplete lineage as the main figures – say two or four masters of the Sakyapa Path with Its Fruit instructions – and to surround them with minor figures representing a complete lineage of gurus of another teaching line.[42]

A further possibility was to depict parts of two separate lineages in a single painting: one partial lineage consisting of multiple main figures, and the other as multiple minor figures. Illustrating this is a set of tangka each showing four Path with Its Fruit lineage masters and a half of a second (unrelated) lineage.[43]

Yet another possible complication is that occasionally a lineage branched or forked, and where this was thought significant by the patron, it could be shown by separately portraying both of the two branch lineages in question.[44] Finally, it may happen that two distinct lineages are depicted by the minor figures. This, too, can be viewed as a type of branching; here the split occurs already from the original teacher (e.g. Vajradhara). For example, a tangka can depict two series of minor figures descending to the right and left, each series representing a distinct minor lineage.[45] Or two complete lineages can be shown, each with a separate progenitor.[46]

As one approaches the most recent two or three centuries, moreover, one finds that the lineages are hardly ever painted in complete form. This does not mean that the lineages have become less important religiously, but only that they have become too long to be easily represented in paintings. Instead of a complete lineage, it is now usual to depict a selection of the greatest founding masters and transmitters of the teaching. But this makes the few paintings of complete lineages from the eighteenth through twentieth centuries all the more important.[47]

Standard Groups that Look like Lineages

One has to be careful, moreover, not to identify as teaching lineages all similar-looking arrangements of Indian masters and Tibetan lama. Near the start of the teaching lineage, such figures can, of course, be early members of the lineage. If they appear above (i.e., prior to) the Tibetan lama, then one can provisionally assume that they belong to the lineage. But when they appear as a group below Tibetan lama or elsewhere, one must exercise caution. A row or descending column of Indian paṇḍitas or siddhas might in fact be some standard arrangement of Indian masters such as the Six Ornaments and Two Best Ones (gyen druk chok nyi), Eight Great Adepts (drupchen gyé), or a fraction of the “Eighty-four Adepts,” and not the start of a lineage.

Systematic inclusion of charts and complete lists of figures has the advantage of forcing the investigator to confront unusual features. For instance, repeated or missing teachers of the lineage should not be passed over without at least some attempt at explanation. Though all lama can provisionally be assumed to have been either members of the lineage or (as a final figure) the patron, the presence of unknown or unexpected Indian masters (e.g. siddhas or paṇḍitas) must be explained.

Depictions of trülku (sprul sku) Lineages

Since the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, moreover, there is the increasing danger that a series of previous lives previous lives of a reincarnate lama might have been depicted where one would expect a guru lineage.[48] Above him in the sky are four lama, including at least three of his previous reembodiments as the Zhamar.

Another striking example is Rhie and Thurman no. 51,[49] “Nyingma Lama,” where the main figure is in fact the great seventeenth-century master and historian of Sakya Monastery, Amyezhap Ngakwang Künga Sönam (1597-1659), and the minor figures portray his successive previous lives. The lineage of figures contains a few obvious historical gaps, which makes it doubtful at first glance that an unbroken lineage of masters and disciples was depicted. This series raises difficulties even as a list of a reincarnate lama’s rebirths, since several of the lives overlap conspicuously – Lama Dampa Sönam Gyeltsen (1312-1375) and Tekchen Chöjé Künga Trashi, for instance, being uncle and nephew. Does this reflect sloppy historical scholarship on the part of the person who first “retraced” the lineage of previous lives? It was, however, doctrinally conceivable that an enlightened master could have manifested two different bodily forms or lives simultaneously, though this explanation was somewhat inelegant.

Depictions of Several Teachers of the Same Generation

Another possibly deceptive arrangement is the placement of several teachers, many from the same generation, above the head of the central figure. In this case no single lineage is portrayed, though at first glance it resembles a lineage depiction: for instance, the depiction of Sachen Künga Nyingpo with several lineage and direct teachers in Rhie and Thurman no. 61.[50] The figures portrayed are:

- Dorjé Denpa

- Bora Gyel?

- Belpo Jnanavajra

- Purang Lochung

- Ngok Lotsawa

- Drangti Darma Nyingpo

- Khyung Rinchendrak

- Langkönpa

- Jampel

- Bari Lotsawa

- Birwapa

- Khön Gyichuwa

- Namkhaupa

- Khön Könchok Gyelpo

- Sekhar Chungwa

- Mel Lotsawa

- Jangchup Sempa

- Melha(ng) Tsé

| 1 | 8 | 10 | 12 | |

| 2 | 9 | 11 | 13 | |

| 3 | 14 | |||

| 4 | 15 | |||

| 5 | 16 | |||

| 6 | 17 | |||

| 7 | 18 |

Up to figure no. 5 they are his lineage gurus, and after that all (except maybe no. 8) are his direct teachers. Figures no. 9 and 11 taught him in visions.

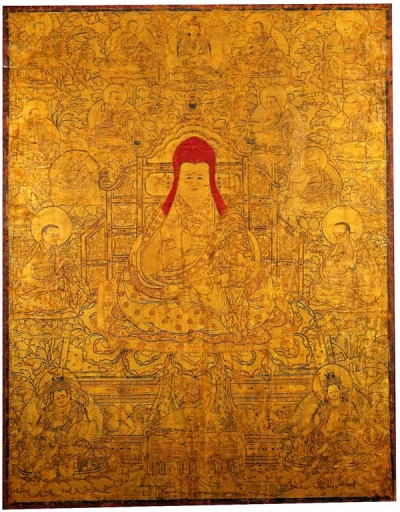

See also H. Kreijger no. 24, “Sakya Master.”[51] This striking monochrome gold painting portrays as its main figure the great sixteenth-century master Sakya Lotsawa Jamyang Künga Sönam of the Sakya Düchö Palace, the twenty-third throne holder of Sakya, tenure 1496-1533. He is shown surrounded by his twelve teachers and the Buddha Vajradhara.

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | ||||

| 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | |||||

| 10 | 11 | |||||||

| 12 | 13 | |||||||

| 14 | Main Figure |

15 |

- Vajradhara

- Jé Könchokpel

- Dakchen Chöje

- Jamyang Sherap Rinchen

- Drupchen Chakdorwa

- Trülzhik Tsültrim Gyeltsen

- Khenchen Künlowa

- Jé

- Ngakchang

- Shakya Senggé

- Chöjé Yöntenpa

- Dongkyepa

- Serchen Chözangpa

- Penchen Drakpa Dorjé

- Lowo Khenchen

To repeat, the twelve lama do not form a lineage. As a young boy, Künga Sönam’s first two main teachers were (14) Minyak Pendita Drakpa Dorjé (d. 1491) and (15) Lowo Khenchen Sönam Lhündrup (1456-1532), who are portrayed as youthful lama to his right and left. I assume that this exquisite gold tangka was commissioned in the great lama’s honor by one of his main students either in the last decades of his life or after he died in 1533 at the relatively young age of 48.

See H. Kreijger no. 18, “Portraits of Six Masters.”[52] Painting with such arrangements are rare. They do not indicate any diminishing of the importance of complete lineages by the time they were painted.

The Historical Accuracy of the Lineages Depicted

Generally speaking, the painted depictions of lineages in carefully executed tangka are an accurate representation of contemporary knowledge and opinion about the particular lineages. Especially for the most recent generations they portray, they can be trusted as a fairly reliable historical record, as can sometimes be confirmed by checking the parallel written sources. In many cases the lama planning the painting must have based themselves on the best available written sources. Sometimes, now, the contents of inscribed painted lineages serve as a rare record of otherwise unattested lineages.

The above comments about historical accuracy, however, mainly refer to the Tibetan portions of lineages. It is possible, especially in very long Indian lineages, that the early Indian segments embody semi-legendary or even legendary materials of limited historical value. Still, one should investigate carefully at least the last few Indian generations, and one should not dismiss out of hand all references to Indian masters.

Conclusions

Depictions of lineages are thus a valuable key for students of Tibetan art. They can help unlock the overall structure, and thus meaning, of many paintings. If accurately interpreted, lineages can be important for a better understanding of the art history, iconography, and even religious culture of Tibet in general.

The Chronological Significance of the Latest Figure

A dearth of precisely datable tangka has long plagued historians of Tibetan painting. Comparison of stylistic elements often allows a provisional dating to within two or three generations. But many paintings contain additional evidence that can be used for a more exact dating, such as written inscriptions that identify individual gurus, the lama who performed the consecration, or even the commissioning patron.

Even without inscriptions, the presence of an identifiable guru lineage often makes possible a more exact dating. If the lineage is complete and has been properly interpreted, the identity of its last figure enables an approximate dating of the patron to within about one generation.[53] This sounds inexact, but being based on internal evidence relating to identifiable historical people the method has several advantages over the more hypothetical conclusions obtained through mere stylistic similarity.[54]

Yet one must be careful not to mistake, for instance, a partial lineage for a whole one. One must also be careful where one or two lama as the main central figure or figures may represent the final figure(s) of the lineage, thus bringing the lineage forward another generation or two. It is essential to try to identify and date as many figures from the end of the lineage as possible, for despite the other complexities of this method, one point is simple: a painting cannot have been painted before the latest historical figure it portrays.

Most historians of Tibetan art would agree that a description of inscribed lineages is essential for documenting in detail the paintings that contain them. Ideally, the documentation should include all four steps:

- Deciphering the names

- Identifying and dating the individual masters

- A. Identification of the entire lineage, and B. listing the names in the chronological order of the lineage

- Diagramming the relative positions of each figure, with numbers corresponding to the list of step 3.

For structural analysis the job is not finished until step 4 is completed. In this article I have concentrated on showing as many possible instances of that step without furnishing for each tangka the steps leading up to it.[55]

The Wider Significance of Lineages

Paintings of guru lineages bear witness to what seems to be a special feature of Tibetan (especially Tantric) Buddhism and even Tibetan culture in general: a strong sense of concrete tradition and history. The fastidious care paid by generation after generation of Tibetans to recording actual lineages in art as well as in ritual practice and similar written lineage records is, as far as I can judge, special within the Asian Buddhist cultural realm. Though rooted in Indian concepts of the guru lineage, these Tibetan expressions of lineage have few close parallels known to me elsewhere in the world. Given the importance of painted lineages in these and other respects, one can only hope that historians of Tibetan art will devote to them the careful attention they deserve.

Glossary

Bibliography

- Béguin, Gilles, ed. Dieux et démons d’Himâlaya: Art du Bouddhisme lamaique. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1977.

- Chayet, Anne. Art et Archéologie du Tibet. Paris: Picard Éditeur, 1994.

- Chogay Trichen. Gateway to the Temple: Manual of Tibetan Monastic Customs, Art, Building and Celebrations. Bibliotheca Himalayica, Series III, vol. 12. Translation by D. P. Jackson of BCo brgyad khri chen, Thub bstan legs bshad rgya mtsho [=Ngag dbang mkhyen rab legs bshad rgya mtsho], Bstan pa’i rtsa ba.... Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar, 1979.

- Essen, G.-W., and T. T. Thingo. Die Götter des Himalaya: Buddhistische Kunst Tibets. Die Sammlung Gerd-Wolfgang Essen. 2 vols. Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1989.

- Everding, Karl-Heinz. Tibet: Lamaistische Klosterkulturen, nomadische Lebensformen und bäuerlicher Alltag auf dem ‘Dach der Welt’. Köln: DuMont Buchverlag, 1993.

- Galerie Robert Burawoy. Peintures du monastère de Ngor. Libourne: Arts graphiques d’Aquitaine, 1978.

- Gerasimova, K. M. “Compositional Structure in Tibetan Iconography.” Tibet Journal 3, no. 1 (1978): 37-51.

- Huntington, John C., and Dina Bangdel. The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Columbus: Columbus Museum of Art, and Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2003.

- Jackson, David. Tibetan Thangka Painting: Methods and Materials. Rev. ed. In collaboration with J. Jackson. London: Serindia Publications, 1988.

- ———. “A Painting of Sa-skya-pa Masters from an Old Ngor-pa Series of Lam ’bras Thangkas.” Berliner Indologische Studien 2 (1986): 181-91.

- ———. “The Identification of Individual Masters in Paintings of Sa-skya-pa Lineages.” In Indo-Tibetan Studies: Papers in Honour and Appreciation of Professor David Snellgrove’s Contribution to Indo-Tibetan Studies, vol. 2, edited by T. Skorupski, 129-44. Tring, U.K.: Buddhica Britanica, 1990.

- ———. “Apropos a Recent Tibetan Art Catalogue.” Review of Wisdom and Compassion, by M. M. Rhie and R. A. F. Thurman. Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens 37 (1993): 109-30.

- ———. A History of Tibetan Painting: The Great Painters and Their Traditions. Beiträge zur Kultur- und Geistesgeschichte Asiens, No. 15. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1996.

- ———. “Lama Yeshe Jamyang of Nyurla, Ladakh: The Last Painter of the ’Bri gung Tradition.” In E. Lo Bue ed., art issue of the Tibet Journal 27 (2002): 153-76.

- ———. “The Dating of Tibetan Paintings is Perfectly Possible–Though Not Always Perfectly Exact.” In Dating Tibetan Art: Essays on the Possibilities and Impossibilities of Chronology from the Lempertz Symposium, Cologne, 2001, edited by I. Kreide-Damani, 91-112. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2003.

- Karmay, Samten G. The Little Luminous Boy: The Oral Traditions from the Land of Zhangzhung Depicted on Two Tibetan paintings. Bangkok: Orchid Press, 1998.

- Kossak, S. and J. C. Singer. Sacred Visions: Early Paintings from Central Tibet. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998.

- Kreijger, Hugo. Tibetan Painting: The Jucker Collection. London: Serindia Publications, 2001.

- Luczanits, Christian. “Art-Historical Aspects of Dating Tibetan Art.” In Dating Tibetan Art: Essays on the Possibilities and Impossibilities of Chronology from the Lempertz Symposium, Cologne, 2001, edited by I. Kreide-Damani, 25-57. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2003.

- Martin, Dan. Tibetan Histories: A Bibliography of Tibetan-Language Historical Works. London: Serindia, 1997.

- Pal, Pratapaditya. Art of Tibet: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection. Rev. ed. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1990.

- ———. Tibetan Paintings: A Study of Tibetan Paintings, Eleventh to Nineteenth Centuries. Basel: Ravi Kumar/Sotheby Publications, 1984.

- ———. Art of the Himalayas: Treasures from Nepal and Tibet. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1991.

- Reynolds, V., A. Heller, and J. Gyatso. The Newark Museum Tibetan Collection. Vol. 3, Sculpture and Painting. Newark: The Newark Museum, 1986.

- Rhie, Marylin M. Weisheit und Liebe: 1000 Jahre Kunst des tibetischen Buddhismus. Bonn: Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1996.

- Rhie, Marylin M., and Robert A. F. Thurman. Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet. New York: Henry N. Abrams, 1996.

- ———. Worlds of Transformation: Tibetan Art of Wisdom and Compassion. New York: Henry N. Abrams, 1999.

- Singer, Jane Casey. “Painting in Central Tibet, ca. 950–1400.” Artibus Asiae 54, no. 1/2 (1994): 87–136.

- ———. “Taklung Painting.” In Tibetan Art: Towards a Definition of Style, edited by J. Singer and P. Denwood, 52-67. London: Laurence King, 1997.

- Sobisch, Jan-Ulrich. “The ‘Records of Teachings Received’ in the Collected Works of A mes Zhabs: An Untapped Source for the Study of Sa skya pa Biographies.” In Tibet, Past and Present: Tibetan Studies I, edited by H. Blezer, PIATS 2000: Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the Ninth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Leiden 2000, ed. Henk Blezer and Abel Zadoks, vol. 2/1, Brill’s Tibetan Studies Library, ed. Henk Blezer, Alex McKay, and Charles Ramble, 59-77. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

- Tanaka, Kimiaki. “The Usefulness of Buddhist Iconography in Analysing Style in Tibetan Art.” Tibet Journal 21, no. 2 (1996): 6-9.

Footnotes

- ↑ G. Tucci, Tibetan Painted Scrolls (Rome: Libreria dello Stato, 1949).

- ↑ See G. Tucci, Painted Scrolls, 369-70, nos. 25-27. The three paintings were evidently the first, fourth, and fifth paintings in a set that originally consisted of eight paintings. The paintings’ minor figures were not randomly selected masters as Tucci guessed, but rather ten or eleven adepts in each painting from the eighty-four siddhas: 8 x 10.5 = 84.

- ↑ Gilles Béguin, ed., Dieux et démons d’Himâlaya: Art du Bouddhisme lamaique (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1977), nos. 109 and 122.

- ↑ In her later book on Tibetan art and archeology, Anne Chayet (Art et Archéologie du Tibet [Paris: Picard Éditeur, 1994], 189), when discussing prospects for future research on Tibetan art, mentioned the analysis of lineages as a problem calling for further investigation, sketching two typical compositional types, one earlier and one later. See also David Jackson, “Apropos a Recent Tibetan Art Catalogue,” review of Wisdom and Compassion, by Marylin M. Rhie and R.A.F. Thurman, Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens 37 (1993): 109-30, which was not yet available to Chayet.

- ↑ Galerie Robert Burawoy, Peintures du monastère de Ngor (Libourne: Arts graphiques d’Aquitaine, 1978).

- ↑ The origin of this, the second of two anonymous sales catalogs of Tibetan paintings by the Burawoy gallery in the 1970s, is unclear to me, but someone in France with competence in Tibetan must have helped the gallery owner, whose main expertise is with Japanese weapons and armor.

- ↑ See for instance Pratapaditya Pal, Art of Tibet: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection, rev. ed. (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1990), with H. Richardson’s documentation of inscriptions in an appendix; G.-W. Essen and T. T. Thingo, Die Götter des Himalaya: Buddhistische Kunst Tibets; Die Sammlung Gerd-Wolfgang Essen, 2 vols. (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1989); Pratapaditya Pal, Art of the Himalayas: Treasures from Nepal and Tibet (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1991), with documentation of inscriptions by H. Stoddard; Hugo Kreijger, Tibetan Painting: The Jucker Collection (London: Serindia Publications, 2001), with documentation of inscriptions by P. Verhagen.

- ↑ For instance, H. Stoddard’s footnote in Pal, Art of the Himalayas, appendix; J. C. Singer, “Painting in Central Tibet, ca. 950–1400,” Artibus Asiae 54, no. 1/2 (1994): 87–136; J. C. Singer, “Taklung Painting,” in Tibetan Art: Towards a Definition of Style, ed. J. Singer and P. Denwood (London: Laurence King, 1997), 52–67; and Kimiaki Tanaka, “The Usefulness of Buddhist Iconography in Analysing Style in Tibetan Art,” Tibet Journal 21-22 (1996): 6-9.

- ↑ Pal et al. 2003; and John C. Huntington and Dina Bangdel, The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art (Columbus: Columbus Museum of Art; Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2003). See also the painstaking documentation of three lineage tangka by C. Luczanits, “Art-Historical Aspects of Dating Tibetan Art,” in Dating Tibetan Art: Essays on the Possibilities and Impossibilities of Chronology from the Lempertz Symposium, Cologne, 2001, ed. I. Kreide-Damani (Wiesbaden: Reichert, 2003), 25-57.

- ↑ See, for instance, David Jackson, “A Painting of Sa-skya-pa Masters from an Old Ngor-pa Series of Lam ’bras Thangkas,” Berliner Indologische Studien 2 (1986): 181-91; David Jackson, “The Identification of Individual Masters in Paintings of Sa-skya-pa Lineages,” in Indo-Tibetan Studies: Papers in Honour and Appreciation of Professor David Snellgrove’s Contribution to Indo-Tibetan Studies, ed. T. Skorupski (Tring, U.K.: Institute of Buddhist Studies, 1990), 129-44; Jackson, “Apropos,” 109-30; David Jackson, A History of Tibetan Painting: The Great Painters and Their Traditions, Beiträge zur Kultur- und Geistesgeschichte Asiens 15 (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1996); David Jackson, “Lama Yeshe Jamyang of Nyurla, Ladakh: The Last Painter of the ’Bri gung Tradition,” in art issue (ed. E. Lo Bue), Tibet Journal 27 (2002): 153-76; and David Jackson, “The Dating of Tibetan Paintings is Perfectly Possible – Though Not Always Perfectly Exact,” in Dating Tibetan Art: Essays on the Possibilities and Impossibilities of Chronology from the Lempertz Symposium, Cologne, 2001, ed. I. Kreide-Damani (Wiesbaden: Reichert, 2003), 91-112. An earlier version of this paper appeared as “Tibetische Thang kas deuten, Teil 1: Die Hierarchie der Anordnung,” Tibet und Buddhismus 50, no. 3 (1999): 22-27; and “Tibetische Thang kas deuten, Teil 2: Übertragungslinien und Anordnung,” Tibet und Buddhismus 50, no. 4 (1999): 16-21.

- ↑ See G. Tucci, Painted Scrolls, 300ff. Tucci also mentions some basic principles in his chapter on the symbolic meanings of colors and lines, 287-88.

- ↑ See K. M. Gerasimova, “Compositional Structure in Tibetan Iconography,” Tibet Journal 3, no. 1 (1978): 47.

- ↑ Gerasimova, “Compositional Structure,” 48f.

- ↑ My remarks here are based mainly on a direct investigation of paintings, though on a few points (especially regarding iconometrical and iconographical classes) I have been influenced by the explanations of learned lama and by written zorik treatises.

- ↑ See G. Tucci, Painted Scrolls, 301.

- ↑ See Karl-Heinz Everding, Tibet: Lamaistische Klosterkulturen, nomadische Lebensformen und bäuerlicher Alltag auf dem ‘Dach der Welt’ (Köln: DuMont Buchverlag, 1993), 92; David Jackson, Tibetan Thangka Painting: Methods and Materials, rev. ed, in collaboration with J. Jackson (London: Serindia Publications, 1988), 35; and Valrae Reynolds, Amy Heller, and Janet Gyatso, The Newark Museum Tibetan Collection, vol. 3, Sculpture and Painting (Newark: The Newark Museum, 1986), 169-71.

- ↑ See Jackson, Tibetan Thangka Painting, chapter 4 and appendix A.

- ↑ See for instance S. Kossak and J. C. Singer, Sacred Visions: Early Paintings from Central Tibet (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), 91, no. 18 [single guru]; and 89, no. 17 [group of three founding lama].

- ↑ See Pal, Art of Tibet, 82, plate 18 [P13]. The structure of this painting has been described in Jackson, “Identification of Individual Masters,” 130-32.

- ↑ See Kossak and Singer, Sacred Visions, 81, no. 13.

- ↑ Here it is interesting to compare the remark of Dan Martin, Tibetan Histories: A Bibliography of Tibetan-Language Historical Works (London: Serindia, 1997), 15: “The nearly universal concern of Tibetan religious schools for ‘lineage’ is a highly historical sort of preoccupation.”

- ↑ On the topyik genre, see Jan-Ulrich Sobisch, “The ‘Records of Teachings Received’ in the Collected Works of A mes Zhabs: An Untapped Source for the Study of Sa skya pa Biographies,” in Tibet, Past and Present: Tibetan Studies I, ed. H. Blezer(Leiden: Brill, 2002), 59-77.

- ↑ See, for instance, Pal, Tibetan Paintings: A Study of Tibetan Paintings, Eleventh to Nineteenth Centuries (Basel: Ravi Kumar/Sotheby Publications, 1984), plates 29 and 30.

- ↑ Chayet, Art et Archéologie, 189, noted such a convention among early tangka.

- ↑ See Marylin Rhie and R.A.F. Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet (New York: Henry N. Abrams, 1991), 231, no. 75; and Pal, Art of the Himalayas, 152, no. 85.

- ↑ See Pal, Art of the Himalayas, 149, no. 83, where the three central figures of the next row, however, are deities, and it may be that figures 14 and 15 appear twice (otherwise the last four figures are 16, 17, 18 and 19).

- ↑ Samten G. Karmay, The Little Luminous Boy: The Oral Traditions from the Land of Zhangzhung Depicted on Two Tibetan Paintings (Bangkok: Orchid Press, 1998), 3, caption 1.

- ↑ See Pal, Art of the Himalayas, 155, no. 87.

- ↑ Rhie and Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion, 221, no. 70.

- ↑ See Singer, “Taklung Painting,” 55, plate 37; and Singer, “Painting in Central Tibet,” 126, plate 25.

- ↑ Singer, “Taklung Painting,” 59.

- ↑ Rhie and Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion, 222, no. 71.

- ↑ Rhie and Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion, 234.

- ↑ See M. Rhie and R. Thurman, Weisheit und Liebe: 1000 Jahre Kunst des tibetischen Buddhismus (Bonn: Kunst-und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 1996), 449, no. 203 (84a).

- ↑ Chayet, Art et Archéologie, 189, mentions this order beginning at the top, center, and alternating to both sides as a usual later convention. She records a tradition according to which this convention was introduced in the Sakyapa school by Tekchen Chöjé Künga Trashi (1349-1425). This suggestion is interesting because that master visited the Ming court in the first decade of the fifteenth century, and brought back to Tibet much Chinese Buddhist art, which was later much admired and even taken as models.

- ↑ Rhie and Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion, 207.

- ↑ The identical structure of another tangka from this series has been described in Jackson, “Identification of Individual Masters,” 138f. For a still later painter with the same basic structure, see Pal, Art of Tibet, 88, plate 24 [P21], a painting described in Jackson, “Identification of Individual Masters,” 139-41.

- ↑ Kreijger, Tibetan Painting, no. 56.

- ↑ Kreijger, Tibetan Painting, no. 66.

- ↑ See Ngor chen kun dga’ bzang po, Thob yig rgya mtsho, in Bsod nams rgya mtsho, ed., Sa skya pa’i bka’ ’bum (Tokyo: Toyo Bunko, 1968), 9: 84.1-2.

- ↑ This was probably the case in Pal, Tibetan Paintings, plates 35 and 41; and Pal, Art of the Himalayas, 155, no. 87.

- ↑ See for instance Jackson, A History, 81, figure 24.

- ↑ See Pal, Art of Tibet, 84, plate 20 (P15). The structure of this painting has been described in Jackson, “Identification of Individual Masters,” 132-36.

- ↑ See Pal, Art of Tibet, 82, plate 18 (P13). The structure of this painting has been described in Jackson, “Identification of Individual Masters,” 130-32.

- ↑ See Rhie and Thurman, Weisheit und Liebe, 440, no. 192 [16a].

- ↑ As in Reynolds et al., Newark Museum, plate 11 (P12).

- ↑ See, for instance, the important recent Drukpa lineage in Pal, Tibetan Paintings, plate 95 (inscribed). Recent Drigungpa lineage tangka are not that rare. See Jackson, A History, 343, plate 64; and Jackson, “Lama Yeshe Jamyang,” 153-76.

- ↑ See, for example, Rhie and Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion, 251, no. 87, where the main figure is a Zhamar Rinpoché – probably the fourth, Chödrak Yeshé (1453-1524).

- ↑ Rhie and Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion, 184.

- ↑ Rhie and Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion, 201.

- ↑ Kreijger, Tibetan Painting, 78.

- ↑ Kreijger, Tibetan Painting, 66.

- ↑ For a more detailed discussion of the chronological possibilities of this method, see Jackson, “Dating of Tibetan Paintings,” 91-112.

- ↑ It will be possible in some paintings to test the accuracy of dating by lineage (and to confirm whether the patron belonged to the generation after the last guru of the lineage), namely in those tangka that possess both an inscribed lineage and inscriptions mentioning the name of the patron and the occasion for the painting being commissioned.

- ↑ I have given more complete documentation of numerous tangka in recent publications, and plan to present more in the future.

Source

David Jackson, “Lineages and Structure in Tibetan Buddhist Painting: Principles and Practice of an Ancient Sacred Choreography,” Journal of the International Association of Tibetan Studies, no. 1 (October 2005): 1-40, http://www.thlib.org?tid=T1220 (accessed March 22, 2014).