(Local deities)

a local deity is an intelligent deity or magical power that resides in a place.

Very few local deities of this form are able to move from their native area, either because they are "part of the land" or because they are bound to it.

Local deity are usually portrayed as being extremely powerful and usually also very intelligent, though there is a great deal of variability on these points.

Some versions are nearly omnipotent and omniscient inside the area they inhabit, while others are simply vast, semi-sentient wellsprings of magical energy.

This power almost never extends beyond the border of the local deity it means place were they reside...

Different settings give different explanations for the existence of local deity.

In most cases, however, the intelligent, magical entity simply develops from the similarly named "spirit of place" over a great deal of time.

In other settings, local deity are formed by powerful magical events,

Local Deities

Along many paths in the countryside, and in some urban neighborhoods, there are sacred spots at the base of trees, or small stones set in niches, or simply made statues with flowers or a small flame burning in front of them.

These are shrines for deities who are locally honored for protecting the people from harm caused by natural disasters or evil influences. Worshipers often portray these protectors as warriors, and, in some cases, they may be traced back to great human fighters who died for their village and later became immortalized.

In South India, there are thousands of hero stones, simple representations of warriors on slabs of stone, found in and around agricultural settlements, in memory of nameless local fighters who may have died while protecting their communities hundreds of years ago.

At one time, these stones may have received regular signs of devotion, but they are mostly ignored in contemporary India.

In the fields on the outskirts of many villages, there are large, multicolored, terra-cotta figures of warriors with raised swords or figures of war horses; these are open-air shrines of the god Aiyanar, who serves as the village protector and who has very few connections with the great tradition of Hinduism.

Local deities may begin to attract the attention of worshipers from a wide geographical area, which may include many villages or neighborhoods, or from a large percentage of the members of particular castes, who come to the deity seeking protection or boons.

These deities have their own shrines, which may be simple, independent enclosures with pillared halls or may stand as separate establishments attached to temples of Shiva, Vishnu, or any other great god.

Deities at this level attract expressive and ecstatic forms of worship and tend to possess special devotees on a regular basis or enter into their believers during festivals.

People who are possessed by the god may speak to their families and friends concerning important personal or social problems, predicting the future or clarifying mysteries.

These local gods often expect offerings of animals, usually goats or chickens, which are killed in the vicinity of the shrines and then consumed in communal meals by families and friends.

In the twentieth century, there has been an increase in the number of new, regional gods attracting worshipers from many different groups, spurred by vast improvements in transport and communication.

For example, in the hills bordering the states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala is a shrine for the god Ayyappan, whose origin is uncertain but who is sometimes called the offspring of Shiva and Vishnu in his female form.

Ayyappan's annual festival is a time of pilgrimage for ever-growing numbers of men from throughout South India. These devotees fast and engage in austerities under the leadership of a teacher for weeks beforehand and then travel in groups to the shrine for a glimpse of the god.

Bus tickets are hard to obtain for several weeks as masses of elated men, clad in distinctive ritual dhotis of various colors, throng public transportation during their trip to the shrine.

In northwestern India, the popularity of the goddess Vaishno Devi has risen meteorically since independence. Vaishno Devi, who combines elements of Lakshmi and Durga, is an extremely benevolent manifestation of the eternal virgin who gives material well-being to her worshipers.

One million pilgrims travel annually to her cave shrine in the foothills of the Himalayas, about fifty kilometers north of the city of Jammu.

Since the 1950s, the most spectacular example of a deity's increasing influence throughout northern and central India is the cult of Santoshi Ma (Mother of Contentment).

Her myths recount the sufferings of a young woman left alone by her working husband and abused by her in-laws, who nevertheless remains loving and faithful to her man and, by performing simple vows to the goddess (fasting one day every week), eventually sees the return of her now-rich husband and moves with him into her own house.

Santoshi Ma, thought to be the daughter of Ganesh, is worshiped mostly by lower middle-class women who also pray for material goods. In the 1980s and early 1990s, her shrines were spreading everywhere and even taking over older temples, aided by the release in the 1970s of an extremely popular film version of her story, Jay Santoshi Ma .

Buddhist cosmology recognizes several kinds of divine or semidivine beings, all endowed with superhuman faculties: buddhas and bodhisattvas;

former disciples of the Buddha (sravakas); saints of various kinds (arhats in particular); angelic figures (gandharva, kinnara); "gods" proper (Sanskrit devas; Japanese kami; Burmese nats);

anti-gods (asura); various kinds of ghosts; demonic and monsterlike figures (preta, yaksha, rakhasa); mythological animals (naga, garuda, mahoraga); and devils and other denizens of hell.

Each of these classes has its own place in cosmology and its role in soteriology.

Even though Buddhist cosmology attributes a clear preeminence to the Buddha and other enlightened beings, local deities still play an important role in the life and the liturgy of Buddhists in many parts of the world.

Buddhism and local deities: approaches and problems

The role and status of divinities within the Buddhist tradition is complicated. Deities are often seen as something essentially different from "true" Buddhism (however defined). Negative views consider the worship of local gods as a deluded, superstitious practice.

In general, however, divinities are treated as skillful means (upAya), as a concession to popular beliefs that can be useful to guide the unenlightened toward salvation. Only in some cases are there specific attempts to give doctrinal legitimacy to local deities as full-fledged components of the Buddhist universe.

Despite the ambiguous doctrinal position of deities in the Buddhist system, it is important to emphasize that interaction with local divinities was a key factor in the diffusion of Buddhism, both inside and outside of India. Unfortunately, little information is available on the relationship between Buddhism and local deities in premodern times.

Wherever Buddhism is the dominant or state religion, folkloric practices and traditions concerning local deities have often been downplayed as mere "superstition." Nativist movements in East Asia, in contrast, have tended to reduce the role of Buddhism in their countries and to emphasize instead the autochthonous tradition, with the result of often rendering invisible the connections between Buddhism and local divinities.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Overview of Subject

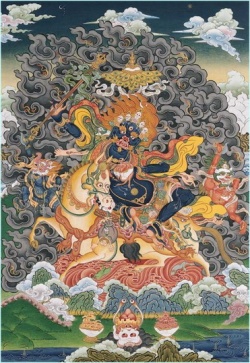

The Tibetan cultural landscape is overrun with the lives, adventures, and influences of innumerable gods and demons, both foreign and autochthonous.

These deities play a significant role in shaping the religious history of Tibet and continue to have a strong presence in the daily practice and worship of Tibetans.

Furthermore, numerous dieties and supernatural entities are elicited in the process of defining every facet of Tibetan cultural history.

If a king is oppressing Buddhism, as in the case of Lang Darma in the 9th century, he is believed to be possessed by a demon, and thus must be subjugated (i.e., assassinated).

Conversely, the Tibetan Buddhist kings were believed to be possessed by demons by practitioners of Bön, who were being persecuted in the 7th and 8th centuries.

The Tibetan people believe themselves to be descended from gods and demons from various realms of the intermediate spaces, as well as from emanations of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara and the goddess Tara.

Also, many religious adepts are believed to be emanations of important bodhisattvas.

The Tibetan landscape istself is thought to be teeming with spirits, which is the reason given for why Tibet is such a harsh environment; indeed, the very land is said to be a giant reclining demoness.

Tibetan medical texts describe the various demonic species that cause numerous kinds of ailments, and how to expel those demons in the process of healing.

In Tibetan Buddhism and Bön, gods and demons play a strong pragmatic role in the daily and annual rituals of both lay and monastic communities. To this day, gods and demons inhabit every part of Tibetan life and are essential for social cohesion.

This ubiquitous nature of Tibetan divinities is in many ways analogous to language. They communicate a collection of symbols that adhere to a common understanding of the world within Tibetan society.

These symbols are anthropomorphic "sentences" sharing similar modules of meaning—such as coloration, iconography, weaponry, mythology, narrative history, textual tradition, activity, and locale—yet combined in different permutations to represent unique instances by which to express shared ideas.

Like languages, these ideas are developed naturally in communal settings, and only after the fact is an artificial structure applied to them that can never quite encompass the whole, always having to make room for countless exceptions; consider the shifting taxonomy of demonic species and the fluctuating hierarchical assigning of various deities to either the worldly ('jig rten pa'i bsrung ma) or transcendent ('jig rten las 'das pa'i bsrung ma) class (not to mention malevolent and tantric designations).

Also like language, there are many regional variations and idiomatic forms. Thus, just as any language is important in the process of making sense of a given culture, so too is this language of the gods essential in the development of a greater understanding of Tibetan culture and religion.

Therefore, it is important to study Tibetan deities, where they come from, how they evolve, what rituals they're associated with, and how they impact Tibetan social forms. To this end, the following bibliography on scholarship concerning Tibetan deities and deity cults is provided.

State of Scholarship

The state of scholarship concerning Tibetan deities and deity cults is still very nascent and quite scant. The below bibliography represents a close to exhaustive survey of primarily secondary resources, with a number of prominent (but by no means exhaustive) primary Tibetan sources.

The majority of these sources are by western scholars trained in Tibetan studies writing in the last half century, with Tibetan sources ranging from contemporary to centuries old.

The most important authors are Stephan Beyer, A. M. Blondeau, René de Nebesky-Wojkowitz, Todd Gibson, Amy Heller, Samten Karmay, and Richard Kohn.

While these authors are generally very full in focus, the majority of the below sources are quite scattered and run the gamut on focus, specificity, historical scope, and methodological approach (not always successfully).

A good deal of the work being done is anthropological in nature, which has produced a sizeable amount of theoretical work that nonetheless needs to be enhanced with more textual and ethnographic data overall.

For the most part, despite the importance and ubiquitous presence of deities and their cults in Tibetan religious history and practice, very little research has been conducted on Tibetan deities compared to the overwhelming scholarship on Tibetan Buddhist philosophy.

It would seem that a preferential bias still exists toward the high value of Buddhist philosophy and the belief that it is the core of Buddhist religion.

In this regard, it's understandable that anthropologists have a degree of purview with Tibetan deities, since they focus on the lived traditions of Himalayan communities, which very overtly involve a constant association with deity cults and related holidays, festivals, and rituals.

However, historical and textual scholarship on deities continues to grow (especially through French scholarship).

The books, collections, and articles enumerated below are still excellent resources for an evolving focus on Tibetan Buddhist deities and deity cults, as well as their innumerable related rituals.

Contributors

Introduction to Tibetan Deity Cults

The following sources are considered rudimentary in that a focus on Tibetan gods and demons and deity cults is their central concern. Given the poor state of scholarship on Tibetan deity cults, these sources are informative but can be greatly improved by further research.

"Ancient Civilization in Tibet aims to comprehensively document the cultural and religious history of a neglected but vital part of Tibet, the Divine Dyads of the Byang thang. This work marshals a wide variety of resources in expounding the history and culture of these two areas, each revolving around a mountain and lake of epic geographical and mythological proportions. The focus of this work is the development of indigenous religion and mythology in these areas and its impact on the culture of the Byang thang and Tibet in general." - book jacket

While full of a great deal of information on sacred geographic sites in Tibet and their related deities, Divine Dyads lacks a strong theoretical background and is prone to a number of false assumptions and biases.

Nearly sixty years after its first publication, Oracles and Demons of Tibet is still considered the most comprehensive treatment of Tibetan gods, demons, and oracles.

This, beyond anything else, is an indicator of how nascent the field still is, and how much research has yet to be done.

That the text is old does not necessarily make it obsolete, as its approach is primarily synchronic and descriptive, but it does severely date it. The text contains obscure or incorrect information that has since been responsibly clarified in more recent scholarship.

De Nebesky-Wojkowitz conducted his research between 1950 and 1953 in the town of Kalimpong on the Indo-Sikkimese borderland.

His resources were three learned Tibetans and their individual, though nonetheless impressive, reservoirs of Tibetan texts. As such, the bulk of de Nebesky-Wojkowitz's information rests on very limited resources despite the extensive text citations within the book.

Also, the text is not especially friendly to non-specialists; he continues to use many Tibetan words in their transliteration without phonetic equivalents or translations in several instances.

The general style of the writing also makes it especially difficult material even for specialists.

The book's greatest deficiency is its lack of explicit organization.

The table of contents does a cursory job of categorizing various deities; beyond this, the individual chapters are little more than extensive and unorganized descriptions of these deities's attributes.

There is no grand unifying methodology tying these descriptions to the greater cultural and ritual traditions of Tibet, and thus there is no concise statement on their importance and relationship to Tibetan religion.

There is some social and political information provided with regards to oracles, protective rituals, and sorcery, but beyond that the book is primarily a compilation of important but disconnected strands of information.

The book, like its individual chapters, starts and ends abruptly with no solid connections.

Despite these weaknesses, Oracles and Demons of Tibet provides a wealth of information and is groundbreaking in its scope.

It continues to be the springboard from which later works on Tibetan deities begin their investigation and is thus an excellent starting point for deeper scholarship.

Gibson's dissertation is an excellent historical exposé on a specific type of Tibetan deity called btsan. This work has a great deal of theoretical structure and relies on several primary documents to support Gibson's conclusion that btsan demons were created in the wake of the fall of the Tibetan dynasty and its sacral kingship, with btsan becoming fierce symbols of a frustrated royalty denied continuance in Tibetan political history. Gibson's methodological foundation is strong and he relies on a great deal of good textual analysis in the course of his research.

He further examines cultural influences, such as parallel deities found in Iranian and Mongolian contexts. Gibson's confident historical approach is particularly informative, and that, matched with good theoretical groundwork and a sizeable sampling of Tibetan manuscripts, all work to create as a strong piece of scholarship that far outweighs its otherwise limited focus.

If more studies on Tibetan deities like this were produced, perhaps on other important types of deities, the field would be greatly advanced.

Collections on Tibetan Deity Cults

These works comprise both western and Tibetan collections focusing on Tibetan deities and their cults.

The western sources are collections of articles by notable scholars in the field, while the Tibetan sources are compilations on the basics of individual deities, the information of which they culled from several sources (which they usually noted) and provided verbatim.

The western sources provided are the only two major collections that concern scholarship on Tibetan deities and deity cults.

Achard, Jean-Luc, ed. 2002. Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines 2: Numéro Spécial Lha srin sde brgyad. Paris: Langues et Cultures de l’Aire Tibétaine.

Blondeau, Anne-Marie, ed. 1998. Tibetan Mountain Deities, Their Cults and Representations. Wien: Verlag Der Österreichischen Akademie Der Wissenschaften.

In scope and research this collection is a wealth of information on Tibetan deities and their cults.

Tibetan Mountain Deities demonstrates the trend in Tibetan deity studies not only toward more anthropological methodologies but also toward more limited focus, with the majority of its articles centering on a specific deity or ritual cult.

With a strong ethnographic angle, national identity has also become a major concern, as further illustrated by Karmay 1998d and 1998e (see below).

Notable articles are Hildegard Diemberger's "The Horseman in Red: On Sacred Mountains in La stod lho (Southern Tibet)," Guntram Hazod's "bKra shis 'od 'bar: On the History of the Religious Protector of the Bo dong pa," and Elisabeth Stutchbury's "Raja Gephan - The Mountain Protector of Lahul."

Blondeau, Anne-Marie, and Ernst Steinkellner, ed. 1996. Reflections of the Mountain: Essays on the History and Social Meaning of the Mountain Cult in Tibet and the Himalaya. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Bstan 'dzin rgya mtsho, ed. n.d. Snga 'gyur rgyud 'bum las btus pa'i gtam rgyud phyogs bsgrigs. gse rta dgon po'i par khang.

This relatively new resource (early 21st century) is published only by Serta (gser rta) monastery in Kham. It is a compilation of the brief mythic histories of the deities discussed in the Collection of the Nyingma Tantras (snga 'gyur rgyud 'bum).

These individual histories are culled from different sources, seemingly copied verbatim, though with a few minor spelling variations or textual addendums. As a primary resource, this text is a good source not only for an outline of various deities but where one can begin searching for related primary documents.

Kong sprul Blo gros mtha’ yas. 1976. Rin chen gter mdzod chen mo: a reproduction of the Stod-lu? Mtshur-phu redaction of ’Jam-mgon Ko?sprul’s great work on the unity of the gter-ma traditions of Tibet, with supplemental texts from the Dpal-spu?s redaction and other manuscripts, vols. 59-63. Paro: Ngodrup and Sherab Drimay.

These volumes in the Mahayoga section of the famous Rin chen gter mdzod chen mo—compiled in the nineteenth century—are extensive collections of sadhanas dedicated to Dharma protectors.

Macdonald, A. W. 1967. Matériaux pour l'Étude de la Littérature Populaire Tibétaine. 2 vols. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Being a collection of popular stories, the first volume of this text consists of a number of vignettes, found in the text the Gold Vetala composed by Nagarjuna, concerning a series of interactions with various types of Tibetan deities.

Some compelling examples are "La fille Sla?-na sla?-chu? qui, parce qu'elle s'était rendue propice sa divinité tutélaire dans ses vies antérieures, revint du pays des bcan qui protègent les grottes, et prit le gouvernement" and "La fille qui, bien que trompée par une srin-mo, grâce à sa propre mère qui était une jñana-?akini, a obtenu d'être reine, une fois sa mauvaise action rachetée."

The second volume has a chapter that is particularly significant to Tibetan deity studies, which is entitled, "Vajrapa?i et la déesse Marici qui, dans leurs naissances successives, ayant assujetti les huit catégories de dieux et de démons, firent régner le bonheur dans le monde."

Sle lung rje drung Bzhad pa’i rdo rje. 1979. Dam can bstan srung rgya mtsho’i rnam par thar pa cha shas tsam brjod pa sngon med legs bshad, 2 vols. Leh: T. S. Tashigang.

Like the work previously mentioned (Bstan 'dzin n.d.), this is equally a collection of the mythic biographies of various deities, though it is an 18th-century resource.

Besides the rich iconographic and mythological details it provides, each biography points to other Tibetan texts—some of which are obscure—that can provide more information about each protector deity.

The text comes with iconographic descriptions of each deity as well as drawings to complement the descriptions.

Three other editions are available: Thimphu 1976, Paro 1978, and Beijing 2003.

Rituals related to Tibetan Deity Cults

Not surprisingly, deities are very closely aligned to rituals, for it is through the latter that Tibetan practitioners willfully engage with the former. In the Tibetan context, deities can too often be pernicious, even those deities supposedly subjugated and reassigned as protectors of the Buddhist teachings.

Because of this, many Tibetan rituals are enacted in part to subdue these deities yet again and employ them in the service of Buddhism more abstractly, or for the purposes of the practitioner and their institution more pragmatically.

Ritual overall is a means to control the environment, the future, or one's soteriological destiny, and since deities in the Tibetan context tend to be various personifications of all these forces, ritual plays a very important part in Tibetan deity cults.

Like deity cults, scholarship on Tibetan ritual in general has received very little attention in comparison to Tibetan scholasticism and philosophy, and so it is an area of research greatly in need of improvement.

As de Nebesky Wojkowitz's Oracles and Demons of Tibet is the first source to approach with regards to Tibetan deities, likewise is The Cult of Tara the first source for Tibetan ritual.

While Beyer's scope is trained primarily on the bodhisattma Tara, this is an incredibly extensive work, focusing on numerous rituals, their contexts and implements, overall.

It should be noted that given the time period in which this book was published, there are about thirty pages of unnecessary speculation into the psychedelic experiences such ritual practices supposedly engender.

It also has numerous spelling errors. Despite these fallbacks and it being over thirty years old, this text continues to be an indispensable resource for rituals and their connection to deity cults.

Oracles in Tibetan Deity Cults

While rituals are very concrete engagements with Tibetan deities, oracles are even more so, representing a very real social element through which deities can interact with people.

As the term suggests, a Tibetan oracle is a member of a community, or in some instances a political institution, who becomes possessed by a specific deity in order to provide communal advice or prophetic pronouncements.

In many instances of trance possession, an oracle could be possessed by multiple deities in succession beyond the particular one they're known to embody, and are expected to help resolve conflicts between monastic communities as well as between individual patrons of the lay community.

Since it has already been listed, de Nebesky-Wojkowitz's Oracles and Demons of Tibet is not provided below, but it remains equally an important resource on Tibetan oracles as well as deities, and indeed could be considered the first resource for this topic as well.

Conversely, of the resources offered below, none stand out as a comprehensive survey of oracles, though Sophie Day's dissertation comes close with its strong ethnographic focus.

A sampling of them all would do more to provide an overall impression. Lastly, if this bibliographic enumeration of Tibetan oracles is not exhaustive, it certainly comes close; this is said in order to illustrate just how little research there has been on the subject.

Sacred Places in Tibetan Deity Cults

In Tibet especially, deities are very strongly tied to locations and to sacred places. This association precedes and transcends their residency at monasteries.

Many indigenous deities are strongly linked to and even conflated with mountains or lakes where they are said to reside, so much so that these locales share the same name with these deities in many instances.

The importance and innate sacred nature of places only intensified in Tibet after the introduction of the ma??ala, the ultimate cosmic and mythographic diagram of space and place, with its key feature being its population of deities.

Therefore, the below resources, while not exhaustive, represent a sampling of important scholarship in regards to sacred places generally and in relation to Tibetan deities specifically.

While again there has been no comprehensive treatment on the subject, the resources provided offer a strong amount of scholarship that could be furthered with future research. Notable sources are Gyatso 1987, Huber 1999, all three Karmay 1998 sources, and Miller 2003.

Specific Studies on Tibetan Deity Cults

These sources represent the handful of books and articles that have treated specific Tibetan deities and their cults beyond those included above in relation to collections, rituals, or oracle traditions.

These works are sparse but highly detailed and focused. They provide very useful methodological approaches to Tibetan deity studies.

Both Macdonald 1978 articles are particularly powerful pieces with regards to relating deity cults to political institutions and hegemonic shifts (though centered specifically on the 16th-century). Overall, these works are excellent templates for future approaches.

Tibetan Deity Cults in History and Texts

An effective approach to Tibetan deity studies has been an historical one structured with textual evidence.

The following sources illustrate this methodology and are thus excellent templates for future studies with regards to diachronic perspectives.

Notable sources are Cuevas 2003, which explores the famous Tibetan text the Great Liberation upon Hearing in the Intermediate State (bar do thos grol chen mo) and its derivation from a much larger body of texts focused on peaceful and wrathful deities, and Mills 2003, which explores the complex (and often ignored) relationship between monasticism, cosmology, deities, oracles, and local practices (though in a specifically Geluk monastic context).

Martin 1996a is also a good exploration of a specific historical instance where popular religious movements associated with a certain deity were historiographically ignored as part of the effort by the validating power to challenge and eventually reject their legitimacy.

This book provides English translations of two famous German articles by Eugen Pander, Das Lamaische Pantheon (1889) and Das Pantheon des Tschangtscha Hutukhtu (1890), which analyze and enumerate 300 xylographic images of spiritual masters, Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, heroes (dpa’ bo), ?akinis, and guardian deities.

This is an eighteenth-century pantheon composed by the third Lcang skya Rol pa’i rdo rje. The two Pander articles are prefaced by an ordered index and analysis of the pantheon by Lohia, the sister of Lokesh Chandra. Each figure in the pantheon is provided with a Tibetan, Sanskrit, and Chinese (Wade-Giles) name.

Bön Deity Cults

The Bön religion of Tibet is intimately tied to Tibetan Buddhism. It is complicated by the fact that it is difficult to assess where exactly Bön ends and Tibetan Buddhism begins, or vice versa.

There are a number of similarities between the two traditions, one of which being deity cults. Given the limited scholarship that exists on Tibetan Buddhist deity cults, there is even less regarding Bön.

Nonetheless, Bön is an important tradition of Tibet and it deserves a great deal more attention. Likewise, gods, demons, and protector deities in Bön also deserve more attention, and this section lists the scant resources that exist concerning Bön deity cults.

A

Brief Discussions of Tibetan Deity Cults in Broader Resources

This list of resources illustrates what one will commonly discover when searching for sources on Tibetan deities. Beyond the explicit sources listed above, the majority of discussions about deities is usually found as a subsection of much broader treatments of Tibetan religions.

What's more, this discussion tends to be secondary to the central focus often given to Tibetan monasticism, philosophy, and scholastic or textual history.

Beyond those Tibetan texts provided or translations of such (Blo bzang 1982, Gyaltsen 1996, Sørensen 1994, Wangdu and Diemberger 2000), none of these sources give a great deal of attention to Tibetan deities and their cults, but they are good, at times cogent, brief introductions in English.

The two exceptions are Kapstein 2000 and Mumford 1989, both of which give adequate theoretical attention to deity cults regardless of the broader focus of their works.

Except for de Nebesky-Wojkowitz's Oracles and Demons of Tibet, it is through these resources that most will have been introduced to Tibetan deities.

Stein 1972 and Tucci 1988 are particularly telling in that both have relegated Tibetan deities to the purview of an almost separate folk religion, distinct from the (seemingly more Buddhist) elements of monasticism.

A subtle acceptance of this trend is noticeable in several of the other works cited below as well.

External Studies related to Deity Cults

To provide a fuller scope of deity cults, it is necessary to at least begin to explore how deities are approached in the scholarship of other related cultures.

The following sources are a sample of such, ranging mainly from China to India, two of the most historically important neighbors of Tibet.

It is specifically with an eye toward potentially untapped methodological approaches that these texts are cited. One notable source is Teeuwen and Rambelli 2003, which actually explores Japanese deity cults and offers a collection of articles that work toward a very sound methodological approach to the assimilation of Buddhist and indigenous deity cults in Japan that could posibly be reworked and applied to the Tibetan context.

As the articles in this text illustrate, Japanese scholars have developed a methodological exploration of a combinatory paradigm (Jap. honji suijaku), in which early indigenous spirit (Jap. kami) cults were eventually assimilated into Buddhist temple liturgical practices.

As such, there appear to be at least superficial similarities in the evolution of seventh- and eighth-century kami temple-shrine complexes in Japan and the mythographic subjugation and conversion of Tibetan indigenous deities.

This may then provide inspiration for developing an equally informative methodological approach to Tibetan indigenous deities and their evolving relationship with the Tibetan assimilation of Buddhism.

This book focuses on various deity and demon cults in Chinese history as it pertains to a number of significant social factors, such as religious evolution, cultural transmission, geography, medicine, and commerce. It is a well-structured and very detailed study that would be useful to mine for methodological approaches to deity cults.

Specifically, there is an excellent discussion in the introduction on vernacular religion and its relationship with elite and state-sponsored religions.