MONGOLIA AND TIBET IN BRITISH- RUSSIAN GREAT GAMES

MONGOLIA AND TIBET IN BRITISH- RUSSIAN GREAT GAMES

Ts. Batbayar (PhD.)

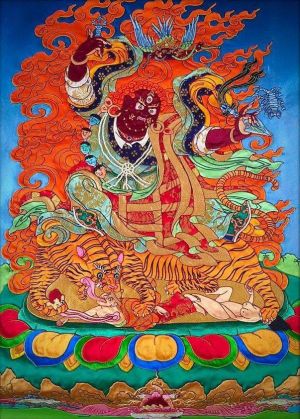

The branch of Buddhism known as the Yellow Hat sect has had a profound influence on all aspects of nomadic Mongolian society since it was first introduced to the Mongols by Altan Khan of Tumed of Southern Mongolia at the end of the sixteenth century. Buddhist monks were referred to as lamas, and the religion itself was known as Lamaism.

The highest lama in the Buddhist hierarchy of Khalkha Mongolia was the [[Jebtsundamba Khutagt[[. His first and second reincarnations were born in the house of Tusheet Khan, which was the most powerful among the four {{Khans[[ of Khalkha Mongolia. As both reincarnations had great political power and were recognized as spiritual leaders of Mongolia, this caused much disquiet within

the Manchu Qing court in Beijing that the Mongols might unite under the lamas leadership. To prevent this from happening the Manchu emperor decreed that the next reincarnations be found not in Mongolia but in Tibet. The 8th and the last reincarnation of the Jebtsundamba Khutagt, was born in Tibet, and brought to Mongolia as a young boy in 1875.

Mongolia and Tibet at the beginning of the twentieth century

At the beginning of the twentieth century leaders of both Mongolia and Tibet faced a dilemma of where to find protection from the Chinese. In the case of Mongolia, following the collapse of the Qing in 1911, it proclaimed its independence and sought help from

Russia. Restrained by its secret treaties with Japan, tsarist Russia, however, was not willing to give full support to Mongolia‟s independence and reunification. In the case of Tibet, it sought protection from Britain against Chinese domination. Britain, which had the Qing acknowledge its interests in Tibet with the 1906 agreement, also was not willing to defend Tibet.

Mongolia and Tibet had two things in common. First, both countries saw their relations with the Qing as based on a special arrangement, and refused to recognize the Republic of China as a successor to the Qing dynasty. Second, both Tibet and Mongolia sought help from abroad to secure

their independence. There is no doubt that the isolated geographical location and the military and political weaknesses of both countries greatly reduced their capabilities in the international arena. The fear of domination and eventual assimilation by China,s huge population has always been at the heart of Mongolian and Tibetan perceptions of Chinese intentions.

The Dalai Lama in Mongolia in 1904-1906

Owing to Francis Younghusband,s infamous expedition to Tibet, the 13th Dalai Lama had to flee to Mongolia in September 1904. This was the first time that the Tibetan monarch had to leave his country, aged twenty-eight at that time.

Charles Bell wrote about the Dalai Lama‟s journey as follows: „Eventually he [the Dalai Lama] crossed the border of Mongolia, inhabited by a race closely akin to the Tibetans, and covering an area more than one-third of the size of Europe. In November he arrived at the capital,

Urga, fairly close to the Russian frontier in the north. Having seven hundred persons in his suite, his baggage was carried by a small army of camels. Over ten thousand citizens went several miles out of the town to meet him and prostrate themselves before him. Pilgrims flocked in from all parts of Mongolia, from Siberia, and from the steppes of Astrakhan, to do him homage.‟

The Dalai Lama stayed for almost two years in Mongolia. At that time Urga was the residence of the above mentioned 8th Jebtsundamba Khutagt. According to Russian archival sources, the relationship between the Dalai Lama and the Khutagt was fraught with tensions, not least because the former‟s stay incurred a considerable financial burden on the latter.

The British were closely following the Dalai Lama‟s exile in Mongolia. Lieutenant-Colonel Waddell, the author of a book entitled The Buddhism of Tibet, wrote in The Times: „The young Dalai bears the title of “the eloquent, noble minded Tubdan”. Temporal sovereign of Tibet, his spiritual authority extends through Tibet and along the Himalayan Buddhist states to Ladak and

Baikal, to Mongolia and China, as far as Peking.‟ Waddell wrote the following about the lama Agvan Dorzhiev, who facilitated the Dalai Lama,s escape to Mongolia: „On his escape from Chinese influence the unlucky young Dalai

soon fell deeply into Russian clutches, through the influence of his favorite tutor, the Lama Dorjieff Dorzhiev. This man is a Mongolian Buriat from the shores of lake Baikal, and therefore a Russian subject by birth and a Lama by profession.

He grew up and received his education in Russia, settled in Lhasa in one of the great convents there 20 years ago…He is a well-educated man, a member of the Russian Geographical Society, and has travelled over India and Ceylon several times on his way to Odessa and

St. Petersburg. Latterly he has been in charge of the arsenal at Lhasa. On getting the ear of the young Dalai Lama he poisoned his mind against the English, and led him to believe that Russia is his friend and not England.‟

There is evidence that while in exile, the 13th Dalai Lama was contemplating the establishment of a „Great Union between Tibet and Mongolia‟. According to Russian sources, the Dalai Lama was determined establish such a Union between Tibet and some parts of Mongolia, including south and north Mongolia. In July 1905 a Russian consular official called Lyuba reported from Urga to his

superiors in Russia that several Mongolian princes from eastern Mongolia had asked the Dalai Lama to advise them on their plan to unite the eastern provinces of Mongolia into a separate kingdom but under the protection of Russia. In reply, so writes Lyuba, the Dalai Lama agreed to support the princes, on condition that Russia was sympathetic to their case.

In September 1905, the Dalai Lama met another Russian consular official called Kuzminskii in Urga to discuss in detail the plan submitted by the Mongolian princes. Among the petitioners were most of the princes of the Jerim aimak (province), two princes from Uzumchin, the Zhasagtu Van of

the Khorchin aimak, two princes from Sunit, and those from eastern and southern Mongolia. During his meeting with the Russian official, the Dalai Lama mentioned that other princes and high ranking lamas, such as Chin Van Khanddorj and the Mongolian Governor of Uliastai, were also supporting the endeavor. The Dalai Lama said that the plan was feasible, although it would take some time to bring it into effect. Asking

Russia to provide moral support for the plan, the Dalai Lama explained that such support would give the Mongolian princes a feeling of protection by Russia with the implication that they could seek shelter in Russia, if needed.

In June 1905, M. Pokotilov, a newly appointed Russian ambassador to China, arrived in Urga on his way to Peking. He met the Dalai Lama and presented him with gifts from the Tsar. Pokotilov reported from Urga on his meeting with the Dalai Lama. The Tibetan sovereign wanted two things: first, to have a special international conference convened by the major powers to discuss the Tibetan issue, and second, to give Russia the same rights and privileges in Tibet, as he did to Britain.

At that time, Agvan Dorzhiev, the Dalai Lama,s tutor, set off to St Petersburg to seek an audience with the Tsar. His mission, however, failed, as John Snelling writes, due to the negative outcome of the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, that pushed the Russian autocracy into deep crisis. Towards the end of his stay in Mongolia, the Dalai Lama travelled to Uliasutai and the Sain Noyon Khan aimak, where he

was welcomed by local princes. Among them, Chin Van Khanddorj, one of the leaders of the National Revolution in 1911-1912, invited the Dalai Lama for a short stay at his monastery called Vangiin Khuree (The Monastery of the Van). The Mongolian historian J. Boldbaatar wrote in this regard that Chin Van Khanddorj benefited greatly from the Dalai Lama,s wisdom.

Treaty between Mongolia and Tibet

In November 1912 the lama Agvan Dorzhiev paid another visit to Urga. During his meeting with the Russian Ambassador Korostovets, Agvan Dorzhiev proposed the establishment of a joint Russian-British protectorate in Tibet thus eliminating Chinese suzerainty over the country. Being cautious, Korostovets advised Dorzhiev to abandon the idea of a joint protectorate and try instead to reach an agreement with the British.

As mentioned above, the international standing of both Tibet and Mongolia was extremely precarious at this time. Both countries had been unsuccessful in securing recognition from the international community. At the beginning of 1913, Mongolia and Tibet, however, signed a treaty of friendship and alliance thus establishing diplomatic relations between themselves. This agreement, consisting of nine articles, was signed by

Agvan Dorzhiev and two other Tibetans on behalf of the Dalai Lama, whilst the Mongolian Jebtsundamba Khutagt was represented by two of his Mongolian ministers. Articles 1 and 2 of the agreement mutually recognized the independence of Tibet and Mongolia, with the

Dalai Lama and the Jebtsundamba Khutagt as head of their respective countries. Article 3 stated that both countries will work for the benefit of the Buddhist faith. Mongolia and Tibet also agreed „to assist each other against internal and external enemies in the present and

future‟. It is highly likely that the agreement was first contemplated by the Dalai Lama during his stay in Mongolia in 1905-06. It is known that he was committed to establishing an alliance with Mongolia based on the religious commonality.

The Mongolian-Tibetan Treaty also obliged each country to provide security for travelers from the other country. The two sides agreed to engage in trade and to set up trading enterprises. A representative of the Tibetan Bank in Urga served as a mediator between the two countries. In connection with this activity, he dispatched regular reports to the Tibetan Prime Minister.

The comparison of Mongolia and Tibet may provide insights into how the world powers operated in this particular region. If Mongolia attracted the interests of China and Russia, then Tibet was considered important to Britain and Russia. Both Mongolia and Tibet

went through similar developments. Just as Russia and China divided Mongolia into Outer and Inner Mongolia in 1913, Sir Henry McMahon devised a plan for the similar partitioning of Tibet into inner and outer zones in December 1913. In terms of timing, the Simla Accord to define the future of Tibet took place from October 1913 to June 1914, while the Kyakhta Conference was held from September 1914 to June 1915.

During the tripartite Simla Accord involving representatives of Britain, China and Tibet, the news of the Mongolian-Tibetan Treaty reached the delegates and was confirmed by the Russians. Taking into account the fact that Russia had a strong influence in Mongolia, the British saw the Treaty as putting Britain‟s interests in Tibet in jeopardy. It was also widely believed that it was the Dalai Lama who appointed [[Agvan

Dorzhiev]] to sign the Treaty with Mongolia. The Prime Minister of Tibet, however, denied this allegation, claiming that Agvan Dorzhiev was asked by the Dalai Lama only to „work for the benefit of Buddhism‟.

The tripartite Khyahta Conference, which took about a year to conclude, was signed by the representatives of Mongolia, Russia, and China on 7 June

1915 in Khyakhta. The agreement, consisting of twenty two points, only reaffirmed the autonomy of Outer Mongolia, while leaving the other Mongolian territories under Chinese suzerainty. According to the agreement, Urga and Beijing were to cease mutual hostilities, and a Chinese amban (governor-general) and Chinese subjects were to be allowed to stay in Mongolia.

The Simla Accord was signed only by Tibet and Britain, with China withdrawing from the treaty, which led to Tibet having an ambiguous status. This resulted in Tibet launching a military campaign in eastern Tibet in 1917-18.

Viewing Tibet and Outer Mongolia as inseparable parts of China, the Republic of China sought ways to re-establish its suzerainty over these territories. In May 1924 the Chinese succeeded in having the Soviet Union formally recognize China‟s suzerainty over [[Wikipedia:Outer

Mongolia|Outer

Mongolia]]. However, following the death of the Jebtsundamba Khutagt, the Soviet Union changed its position and recognized the status of the Mongolian People's Republic, thus setting out to turn Mongolia into a close ally and a Soviet show-case. In 1946, under

the pressure of Joseph Stalin, the Republic of China acknowledged the independence of the Mongolian People's Republic. With regard to Tibet, the Nanking government used the death of the 13th Dalai Lama in 1933, as an opportunity to reassert its control over Tibet. However, this was met with fierce resistance from religious groups in Tibet up until 1951.

Conclusion

Mongolia and Tibet simultaneously declared their independence from the Qing in the early 1910s. Using their shared religion as a platform for cooperation, at the beginning of 1913 the two countries signed a Treaty on friendship and alliance. While in Mongolia in 1904-06, the 13th Dalai Lama may have envisioned a Great Union between Mongolia and Tibet. This idea may have been then led to the formulation of the aforementioned Treaty, which was concluded several years later.

Mongolia and Tibet have been subject to similar political developments up until the end of WW II. The two countries were also objects of keen interest to both Russia and the British Empire, which later became the Soviet Union and Great Britain respectively.

Eventually, Mongolia,s unique geographical location between Russia and China proved to be a decisive factor in gaining independence from its two neighbors.

1 Tsedendamba Batbayar, Modern Mongolia: A Concise History, Ulaanbaatar, 2002, p. 17.

2 Ibid. p. 21.

3 Charles Bell. 1987. Portrait of a Dalai Lama: The life and Times of the Great Thirteenth. Wisdom Publication, London, p.7.

4 The Times, August 13, 1904.

5 Archive of Russian Empire‟s Foreign Policy, Moscow, Fond: Mission in Peking, Opis 761, delo 413. List. 245-247, “Report by Kuzminskii in Urga to G.A. Kozakov in St. Petersburg, 4 September, 1905”.

6 The same Archive, Fond. Mission in Peking, Opis 761, delo 413, list 173, Report by Pokotilov from Urga

7 John Snelling. 1993. Buddhism in Russia: The Story of Agvan Dorzhiev, Lhasa‟s Emissary to the Tsar. Element Books limited, p. 121.

8 J. Boldbaatar. 1995.The Mongolian teacher of the Dalai Lama (in Mongolian). Ulaanbaatar, pp.10-11.

9 I.Y. Korostovets, 2004. From Chinggis Khan to a Soviet Republic (in Russian). Ulaanbaatar, Emgent Printing, pp. 289-291.

10 The bilingual original text of the Mongolian-Tibetan Treaty, the Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ulaanbaatar.