Mahāsāṃghika, Mahasangitika, Mahasanghika

Mahāsāṃghika, Mahasangitika, Mahasanghika

Literally means the Member of the Great Order, majority, community.

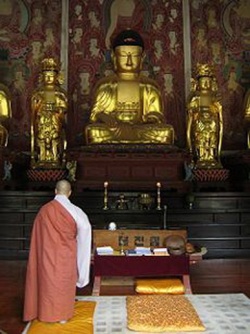

During the First Council, when the Sthavira or elder disciples assembled in the cave after the Buddhas death, and the other disciples (called to be Mahasanghika) assembled outside the cave.

Both compiled the Tripitaka.

However, the former emphasized on the rules of disciplines in the monastic community, while the latter concerned the spread of the spirit of Buddhism in lay community. As sects, the principal division took place in the Second Council.

Mahasanghika and Sthavira are known as two earliest sects in Hinayana.

Mahasanghika is said to be the basis of the development of the Mahayana Buddhism, while Sthavira of the Theravada Buddhism.

For the sub division of Mahasanghika, please refer to the Eighteen Sects of Hinayana.

Originally they had only two divisions the Ekabboharikas and Gokulikas (Rockhill, op. cit., 182ff).

Their separation from the orthodox school was brought about by the Vajjiputta monks, and was probably due to difference of opinion on the ten points (for these see Vin.ii.294f) held by the Vajjiputta monks.

According to Northern sources, however, the split occurred on the five points raised by Mahadeva:

(1) An arahant may commit a sin under unconscious temptation;

(2) one may be an arahant and unconscious of the fact;

(3) an arahant may have doubts on matters of doctrine;

(4) one cannot attain arahantship without the help of a teacher;

(5) the Noble Way may begin with some such exclamation as How sad! uttered during meditation (J.R A.S. 1910, p. 416; cf. MT 173).

These articles of faith are found in the Kathavatthu (173ff., 187ff., 194, 197), attributed to the Pubbaselas and the Aparaselas, opponents of the Mahasanghika school.

According to Hiouen Thsang (Beal.ii.164), the Mahasanghikas divided their canon into five parts:

Miscellaneous and

Fa Hsien took from Pataliputta to China a complete transcript of the Mahasanghika Vinaya. (Giles, p. 64, Nanjios Catalogue mentions a Mahasanghika Vinaya and a Mahasanghabhiksuni Vinaya in Chinese translations, Cola. 247, 253. Ms. No.543).

The best known work of the Mahasanghikas is the Mahavastu. Their headquarters in Ceylon were in Abhayagiri vihara, and Sena I. is said to have built the Virankurarama for their use. Cv.1.68

Mahasanghikah simply means “the Great Assembly,” that is, of monks.

Mahâsanghika; One of the four principal schools in Buddhism according to the I-ching. (During the visit of Fa Hsien to India, 671-695 A.D.)

The Mahasanghikas believed in a plurality of buddhas and held that the Buddha in his earthly existence was only an apparition.

The teachings of the Mahâsanghika School involved the doctrine of the "lokattaravâda" or "supramundane", transcendent Buddha. They described the career of the Buddha as a Bodhisattva prior to his last life as Siddhârtha Gautama. He progressed through ten "stages" ("bhûmis"), elaborated at length in the Mahâvastu, later integrated in the Mahâyana, albeit in modified form.

They also maintain a Bodhisattva can choose to be reborn in the lower realms to soothe its torments and to awaken wholesome factors. These notions are considered to have prepared the ground for the Mahâyâna view and its remarkable Buddhology. Opposing the realistic theories of the Elders, the Mahâsanghikas claim everything (both "samsâra" and "nirvâna") are rooted in the mind.

The Mahasamghika school was the forerunner of the Mahayana movement.

The Mahāsāṃghika, lit. the "Great Saṃgha," was one of the early Buddhist schools in ancient India. The original center of the Mahāsāṃghika sect was in Magadha, but they also maintained important centers such as in Mathura and Karli.

The Mahāsāṃghikas held that the teachings of the Buddha were to be understood as having two principle levels of truth:

a relative or conventional (Skt. saṃvṛti) truth, and the absolute or ultimate (Skt. paramārtha) truth.

For the Mahāsāṃghika branch of Buddhism, the final and ultimate meaning of the Buddha's teachings was "beyond words," and words were merely the conventional exposition of the Dharma.

etymology: The Mahāsāṃghika (Sanskrit: महासांघिक mahāsāṃghika; traditional Chinese: 大眾部; pinyin: Dàzhòng Bù)

Mahāsaṃghika (Skt.). The adherents of the self-styled ‘Majority Community’ or ‘Universal Assembly’, a school of Buddhism which originated in the schism with the Sthaviras that occured after the Second Council (see Council of Vaiśālī) and possibly just prior to the Third Council (see Council of Pāṭaliputra I). The dispute that led to this schism seems to have largely concerned with interpretation of the Vinaya, in respect of which one side took a more liberal approach.

Some of the teachings of this school concerning the nature of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas have features in common with Mahāyāna concepts, but since there is no evidence of innovation by the Mahāsaṃghikas in this respect before the rise of the Mahāyāna, in the view of some scholars, such elements should be ascribed to Mahāyāna influence. According to this view there is thus not much likelihood that the Mahāsaṃghika school played a part in the formation of the Mahāyāna before the latter emerged as a distinct entity. Other scholars see evidence for the converse in the formation of certain Mahāyāna sūtras, such as the Nirvāṇa Sūtra.

One of the two schools formed by the first split in the Buddhist Order about a century after Shakyamuni's death. The other was the Sthaviravada (Pali Theravada) school.

The Great Commentary on the Abhidharma attributes the cause of the schism to controversy over five new opinions set forth by a monk named Mahadeva concerning the modification of doctrine.

One opinion held that those who have attained the stage of arhat retain certain human weaknesses.

Another account of the split regards it as arising from a controversy over a new interpretation of the monastic rules known as the ten unlawful revisions, set forth by the monks of the Vriji tribe in Vaishali.

In either case, the Mahasamghika school accepted the new opinions or interpretations, while the more conservative Sthaviravada school opposed them.

The Mahasamghika school was the more liberal of the two in its interpretation of monastic rules and doctrine.

According to one view, it was the forerunner of the Mahayana movement.

The Mahasamghika school divided repeatedly, and eventually gave rise to eight additional schools.

See also five teachings of Mahadeva; ten unlawful revisions.

Mahasamghika; Aka: Mahasanghika.([大衆部] (Skt; Jpn Daishu-bu);

The Mahāsāṃghika tendency to innovate can be seen also in the content and structure of their Tripiṭaka.

Although in its early stages it is believed to have been comprised of only three parts (Sūtra, Vinaya, and Abhidharma), the Sūtra Piṭaka was later expanded so that the Kṣudraka Āgama became a separate Piṭaka called Saṃyukta Piṭaka.

The most characteristic doctrine of the Mahāsāṃghika group are the famous "Five Points of Mahādeva" (sometimes attributed to a certain Bhadra), an attack on the arhat that has been the object of at least two interpretations: it can be regarded as an argument for more lax moral standards or it can be seen as an indirect way of arguing for the value of the bodhisattva ideal.

These five points are;

that an arhat can be seduced by another (para-upahṛta—meaning that he can have nocturnal emissions accompanied by an erotic dream);

that ignorance (ajñāna) is not totally absent in an arhat (his spiritual insight does not give him knowledge of profane matters);

that an arhat can have doubts (kaṃkṣā);

that an arhat can be surpassed by another (para-vitīrṇa—a term of obscure meaning); and

that an arhat can enter the higher stages of the path by uttering a phrase (vacibheda) such as "Oh, sorrow!"

The exact meaning of these doctrines is far from obvious. Even the general intent is not transparent; one may ask if the Five Points imply that the arhat is more human than he was thought to be in other schools, or that he is weaker than others believe.

Also characteristic of the Mahāsāṃghika is the belief that there are many Buddhas in all of the ten directions and at all times in the past, the present, and the future. In this they differ from more conservative Buddhists who believe that a Buddha is a rare phenomenon.