Making Sense of Tantra

The Meaning of Tantra

The Definition of the Word Tantra

Buddha's teachings include both sutras and tantras. The sutras present the basic themes of practice for gaining liberation from uncontrollably recurring problems (Skt. samsara) and, beyond that, to reach the enlightened state of a Buddha, with the ability to help others as much as is possible. The themes include methods for developing ethical self-discipline, concentration, love, compassion, and a correct understanding of how things actually exist. The tantras present advanced practices based on the sutras.

The Sanskrit word tantra means the warp of a loom or the strands of a braid. Like the strings of a warp, the tantra practices serve as a structure for intertwining the sutra themes to weave a tapestry of enlightenment. Moreover, tantra combines physical, verbal, and mental expressions of each practice, which braid together creating a holistic path of development. Because one cannot integrate and practice simultaneously all the sutra themes without previously training in each individually, tantra practice is extremely advanced.

The root of the word tantra means to stretch or to continue without a break. Emphasizing this connotation, the Tibetan scholars translated the term as gyu (rgyud), which means an unbroken continuity. Here, the reference is to continuity over time, as in a succession of moments of a movie, rather than to continuity through space, as in a succession of segments of pavement. Moreover, the successions discussed in tantra resemble eternal movies: they have neither beginnings nor ends.

Two movies are never the same, and even two copies of the identical movie can never be the same roll of film. Similarly, everlasting successions always maintain their individualities. Furthermore, the frames of movies play one at a time, with everything changing from frame to frame. In the same manner, moments in everlasting successions are ephemeral, with only one moment occurring at a time and without anything solid enduring throughout the successions.

Mental Continuums as Tantras

The most outstanding example of an everlasting succession is the mental continuum (mind-stream), the everlasting succession of moments of an individual mind. Mind, in Buddhism, refers to an individual, subjective, mere experiencing of something and not to a physical or immaterial object that either does the experiencing or is the tool someone uses to experience things. Further, a mental continuum is not a flow of experiences that accumulate such that one person has more experience than does another. A mental continuum comprises simply an unbroken succession of moments of mental functioning - the mere experiencing of things. The things experienced include sights, sounds, feelings, thoughts, sleep, and even death. Mere implies that the experiencing of them need not be deliberate, emotionally moving, or even conscious.

Further, the experiencing of something is always individual and subjective. Two people may experience seeing the same movie, but their experiencing of it would not be the same - one may like it; the other may not. How they experience the movie depends on many interrelated factors, such as their moods, their health, their companions, and even their seats.

Individual beings are those with mental continuums. Each moment of their existence, they experience something. They act with intention - even if not conceptually planned - and subjectively experience the immediate and long-term effects of what they do. Thus, the mental continuums of individual beings - their experiencing of things – changes from moment to moment, as do they, and their mental continuums go on from one lifetime to the next, with neither a beginning nor an end. Buddhism accepts as fact not only that mental continuums last eternally, but also that they lack absolute starts, whether from the work of a creator, from matter/energy, or from nothing.

Individual beings, and thus mental continuums, interact with one another, but remain distinct, even in Buddhahood. Although Shakyamuni Buddha and Maitreya Buddha are equivalent in their attainments of enlightenment, they are not the same person. Each has unique connections with different beings, which accounts for the fact that some individuals can meet and benefit from a particular Buddha and not from another.

Movies maintain their individualities without requiring or containing innate fixed markers, such as their titles, ever-present as part of each moment, giving the films individual identities solely by their own powers. Movies sustain individual identities by depending merely on interwoven changing factors, such as a sensible sequencing of frames. Likewise, everlasting mental continuums go on without innate fixed markers, such as souls, selves, or personalities, that remain unaffected and unchanging during one lifetime and from one lifetime to the next and which, by their own powers, give them individual identities. To sustain their individual identities, mental continuums depend merely on interwoven changing factors, such as sensible sequences of experiencing things according to principles of behavioral cause and effect (Skt. karma). Even on a more general level, mental continuums lack inherently fixed identities such as human, mosquito, male, or female. Depending on their actions, individual beings appear in different forms in each lifetime - sometimes with more suffering and problems, sometimes with less.

The Term Tantra in Reference to Buddha-Nature

Although mental continuums, and thus individual beings, lack innate souls that by their own powers give them their identities, nevertheless they have other features accompanying them as integral facets of their natures. These innate facets also constitute tantras - successions of moments with no beginning or end. The everlasting innate facets that transform into a Buddha's enlightening facets, or which allow each mental continuum to become the continuum of a Buddha, comprise that continuum's Buddha-nature factors.

For example, unbroken successions of moments of physical appearance, communication, and mental functioning (body, speech, and mind), the operation of good qualities, and activity forever accompany the succession of moments of each mental continuum, although the particular forms of the five vary each moment. The physical appearance may be invisible to the human eye; the communication may be unintentional and merely through body language; and the mental functioning may be minimal, as with being asleep or unconscious. Good qualities, such as understanding, caring, and capability, may operate at miniscule levels or may only be dormant; and activity may be merely autonomic. Nevertheless, individually and subjectively experiencing something each moment entails continually having some physical appearance, some form of communication of some information, some mental functioning, some level of operation of good qualities, and some activity.

The fact that unbroken successions of moments of the five innate facets accompany the mental continuum of each being in every rebirth accounts for the fact that successions of the five continue to accompany each being's continuum also as a Buddha. From another point of view, moments of the five continue to occur in unbroken succession even after enlightenment, but now their forms manifest as a Buddha's five enlightening facets. They are enlightening in the sense that they are the most effective means for leading others to enlightenment.

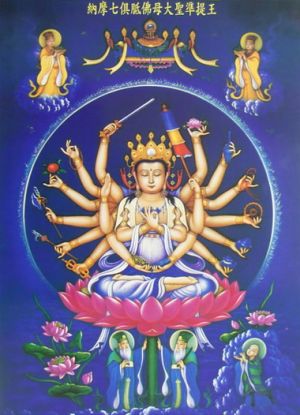

The Role of Buddha-Figures in Tantra

Buddha-figures represent the Buddha-nature factors during refined or "pure" phases when successions of moments of full understanding accompany their continuities. Because Buddha-figures have bodies, communication, minds, good qualities, and actions that work together like an integrated network, they are fit to represent these Buddha-nature factors. Moreover, the figures often have multiple faces, arms, and legs. The array of faces and limbs represent themes from sutra, many of which are also among the Buddha-nature factors. Tantra practitioners use the figures in meditation to further the purification process.

The Sanskrit term for Buddha-figures, ishtadevata, means chosen deities, namely deities chosen for practice to become a Buddha. They are "deities" in the sense that their abilities transcend those of ordinary beings, yet they neither control people's lives nor require worship. Thus, the Tibetan scholars translated the term as lhagpay lha (lhag-pa'i lha), special deities, to differentiate them from worldly gods or from God the Creator.

Summary

The subject matter of tantra concerns everlasting continuities connected with the mental continuum. The continuities include such Buddha-nature factors as basic good qualities, a clear light level of experiencing things, its activity of producing self-appearances, and its voidness. The continuities also include Buddha-figures and the enlightened state. The four traditions of Tibetan Buddhism explain varied ways in which successions of moments of these everlasting continuities intertwine as bases, pathways, and results. They share the feature that tantra involves a pathway of practice with Buddha-figures to purify a basis in order to achieve enlightenment as the result. They also agree that the physical features of the Buddha-figures serve as multivalent representations and provide the warps for interweaving the various themes of sutra practice. The term tantra refers to this intricately interwoven subject matter and the texts that discuss it.

The Four Sealing Points for Labeling an Outlook as Based on Enlightening Words

As an elaboration of Dharmakirti's first criterion for authenticity, Maitreya referred, in The Furthest Everlasting Continuum, to four sealing points for labeling a view as based on the enlightening words of a Buddha. If a body of teachings contains the four, it carries the seal of authenticity as a Buddhist teaching because its philosophical view accords with the intent of Buddha's words. (1) All affected (conditioned) phenomena are nonstatic (impermanent). (2) All phenomena tainted (contaminated) by confusion entail problems (suffering). (3) All phenomena lack nonimputed identities. (4) A total release from all troubles (Skt. nirvana) is a total pacification.

The Buddhist tantric view conforms to the four sealing points. (1) Everything affected by causes and conditions changes from moment to moment. Even with the attainment of enlightenment through the tantra methods, compassion continues to move a Buddha to benefit others in ever-changing ways. (2) As a method for attaining enlightenment, the highest class of tantra harnesses the energy of disturbing emotions such as longing desire. This method, however, completely rids the practitioner of disturbing emotions and the confusion behind them. One needs to rid oneself of them forever because all tainted phenomena bring on problems. (3) After harnessing the energy underlying disturbing emotions such as longing desire, one uses it to access one's clear light continuum. This is the level of mind most conducive for the nonconceptual realization that all phenomena lack nonimputed identities. (4) From this realization of voidness or total absence, one pacifies and thus rids oneself of further successions of moments of the various levels of confusion, their habits, and the problems they bring. The attainment of this total pacification is a total release from all troubles. Thus, the tantric view qualifies as authentically Buddhist.

The Use of Ritual in Tantra Practice

Although tantra practice is extremely advanced, many Westerners receive tantra empowerments without proper preparation and begin tantra practice without deep understanding. Most, at first, see only the surface features of tantra, such as its emphasis on ritual, its profusion of Buddha-figures, and its use of imagery suggestive of sex and violence. Many find these features intriguing, problematic, or, in any case, confusing. To benefit more fully from their initial practice, such Westerners need to understand and appreciate the significance and purpose of these aspects at least on a superficial level. Once they have overcome their initial fascination, objection, or bewilderment, they may slowly examine the deeper levels that the surface conceals.

Western and Asian Forms of Creativity

Tantra practice entails ringing handbells and twirling one's hands with gestures (Skt. mudras), while chanting texts - often in Tibetan without translation – and imagining oneself as a Buddha-figure. Some people find such practice captivating and magical since they can lose themselves in exotic worlds of fantasy. Others have problems with it. Working in an integrated fashion with one's body, voice, and imagination like this is a creative artistic process, yet there seems to be a contradiction. Tantra practice is highly structured and ritualistic, without apparent improvisation. For example, one imagines one's body to have specific postures, colors, and numbers of limbs, with specific objects held in each hand and under each foot. One imagines one's speech in the form of mantras - set phrases consisting of Sanskrit words and syllables. Even one's manner of helping others follows a standard pattern: one emanates lights of specific colors and figures having particular forms. Many Westerners would like to develop themselves spiritually through exploring and strengthening their creativity, but stylized practice of rituals seems antithetical to imaginativeness. Their compatibility, however, becomes evident when one understands the difference between the Western and Asian concepts of creativity.

Being creative in a contemporary Western sense requires producing something new and unique - whether a work of art or a solution to a problem. Invention is the unquestioned highway to progress. Being creative may also constitute part of a conscious or unconscious quest for ideal beauty, which the ancient Greeks equated with goodness and truth. Moreover, most Westerners regard creativity as an expression of their individuality. Thus, for many, following the prescribed models of ancient rituals as a method for spiritual self-development does not seem creative; it seems restrictive.

Most traditional Asian cultures, for instance that of Tibet, view creativity from a different perspective. Being creative has two major facets: giving life to classical forms and fitting them harmoniously within varying contexts. Consider, for example, Tibetan art. All paintings of Buddha-figures follow grids that indicate the size, shape, position, and color of each element according to fixed proportions and conventions. The first aspect of creativity lies in the feeling the artists convey through the expression of the faces, the delicacy of the lines, the fineness of detail, the brightness and hue of the colors, and the use of shading. Thus, some paintings of Buddha-figures are more vivid and alive than are others, despite all drawings of the same figure having identical forms and proportions. The second aspect of Asian-style creativity lies in the artists' choice of backgrounds and manner of placing the figures to create harmonious, organic compositions.

Tantra practice with Buddha-figures is an imaginative method of self-development that is creative and artistic in a traditional Asian, not a contemporary Western way. Thus, imagining oneself as a Buddha-figure helping others differs significantly from visualizing oneself as a superhero or superheroine, finding ingenious elegant solutions to challenges in a noble quest for truth and justice. Instead, one tries to fit harmoniously into the set structures of ritual practice, to bring them creatively to life, and to follow their forms in varying situations to correct personal and social imbalances.

Creativity and Individuality in Tantra Practice

Another factor possibly contributing to a seeming contradiction between practicing tantra ritual and being creative is a difference in contemporary Western and traditional Asian views of individuality and the role it plays in self-development. According to Western egalitarian thought, everyone is equal, but each of us has something unique within us - whether we call it a genetic code or a soul - that by its own power makes us special. Once we have "found ourselves," the goal of self-development is to realize our unique creative potentials as individuals so that we may use them fully to make our particular contributions to society. Thus, contemporary Western artists, nearly without exception, sign their works and seek public acclaim for their creative self-expressions. Tibetan artists, by contrast, usually remain anonymous.

From the Buddhist viewpoint, we all have the same potentials of Buddha-nature. We are individuals, yet nothing exists within us that, by its own power, makes us unique. Our individuality derives from the enormous multiplicity of external and internal causes and conditions that affect us in the past, present, and future. The benefit we may bring to society comes from creatively using our potentials within the context of the interdependent nature of life.

Realizing our Buddha-natures, then, differs greatly from finding and expressing our true selves. Since everyone has the same qualities of Buddha-nature, there is nothing special about anyone. There is nothing unique to find or express. To develop ourselves, we simply try to use our universal working materials - our bodies, communicative abilities, minds, and hearts – in skillful ways to match the ever-changing situations we meet, as anyone can. Moreover, we advance toward Buddhahood by imagining ourselves helping others in hidden anonymous manners – through exerting an enlightening influence and inspiring others who are facing difficulties – rather than by picturing ourselves prominently in the foreground, jumping to the rescue.

Buddha-Figures

To overcome fascination, repugnance, or bewilderment about the dazzling array of Buddha-figures used in tantra and about their unusual forms, Westerners need to understand their place and purpose on the Buddhist path. They also need to differentiate them from the Western concepts of self-images, archetypes, and objects of prayer. Otherwise, they may confuse tantra practice with forms of psychotherapy or devotional polytheistic religion and thus deprive themselves of the full benefits of Buddha-figure practices.

The Use of Buddha-Figures in Practices Shared by Mahayana Sutra and Tantra To gain mindfulness and concentration, one may focus on sensory awareness, for instance of the physical sensation of the breath passing in and out the nose.

For example, becoming a Buddha requires absorbed concentration on love, compassion, and the correct understanding of how things actually exist. If one has already developed concentration with mental awareness, one may apply it to these mental and emotional states more easily than if one has developed concentration through sensory awareness.

Both sutra and tantra Mahayana practices include visualizing Buddha-figures in front of oneself, on the top of one's head, or in one's heart. Tantra practice is unique, however, in its training in self-visualization as a Buddha-figure. Imagining oneself as having the enlightening physical, communicative, and mental faculties of a Buddha-figure acts as a powerful cause for actualizing and achieving these qualities.

Buddha-Figures and Self-Images

Most people have one or more self-images with which they identify. The images may be positive, negative, or neutral, and either accurate or inflated. Buddha-figures, on the other hand, are images that represent only accurate positive qualities.

For example, people may have self-images of being emotionally stiff or mentally slow. They may in fact be tense or dull, but identifying with these qualities as their self-images may easily depress them and dampen their efforts to benefit others. If, on the other hand, they imagine themselves as Buddha-figures whose hearts are warm and whose minds are lucid, they no longer worry about being inadequate. The visualization helps them to access innate positive qualities, especially in times of need.

Furthermore, archetypes are universal features of everyone's collective unconscious, whereas Buddha-figures are collective features associated with everyone's clear light continuum. The clear light continuum is not an equivalent for the collective unconscious. Although both mental faculties have features of which one is normally unaware, the clear light continuum is the subtlest level of the mental continuum and provides an individual with continuity from one lifetime to the next. The collective unconscious, on the other hand, explains the continuity of mythic patterns over successive generations. It manifests in each person, but only in humans, and does not pass on through a process of rebirth.

Moreover, Buddha-figures are neither concrete nor abstract representations findable in a clear light continuum. Nor are they findable elsewhere. Rather, the Buddha-figures represent the innate potentials of everyone's clear light continuum to give rise to patterns of thought and behavior, whether the potentials are unrealized, partially realized, or fully realized. They represent the potentials of general positive qualities, such as compassion or wisdom, rather than the thought and behavior of specific familial, social, or mythical roles. The Buddha-figures associated with disturbing emotions such as anger represent only the transformation and constructive use of the energy underlying the emotions, rather than the destructive negative emotions themselves.

Furthermore, unlike archetypes, Buddha-figures do not come to consciousness spontaneously in dreams, fantasies, or visions unless people have thoroughly familiarized themselves with their forms during their lifetimes or in recent previous lives. This holds true also for bardo, the periods in between death and rebirth. The Tibetan Book of the Dead describes the Buddha-figures that appear during bardo and advises those in the in-between state to recognize the figures as mere appearances produced by their clear light continuums. The people for whom the instructions pertain, however, are persons who have practiced tantra during their lifetimes. Those without previous tantra practice normally experience their continuums giving rise to other appearances during bardo, not those of Buddha-figures.

For example, devotees commonly pray to Tara, as an external being, for protection from fear. Tara may inspire people to be courageous, but the main cause for their overcoming fears is the potentials of their clear light continuums for understanding how things actually exist and the courage that this naturally brings. Inspiration (chinlab, byin-rlabs; Skt. adhishthana, blessing), however, is required for devotees to activate and to use their potentials, and inspiration may come from either external or internal sources. An important Buddha-nature factor, in fact, is the ability of a clear light continuum to be inspired or uplifted.

Tantra practice includes visualizing oneself in the forms of certain historical figures regarded as Buddha-figure emanations, such as Padmasambhava, his female partner Yeshey Tsogyel, or the Second Karmapa, Karma Pakshi. Not all masters regarded as Buddha-figure emanations, however, serve as forms for tantra self-visualization, for example the Dalai Lamas as Avalokiteshvaras. Moreover, political reasons may have motivated the Tibetans to address honorifically certain rulers as Buddha-figure emanations, such as the Manchu emperors of China as Manjushris and the Russian czars as Taras. Tantra practice does not include such persons. Regarding them as emanations, however, accords with the general Mahayana advice to avoid speaking badly of anyone, because one can never tell who may be a bodhisattva emanation.

Buddha-figures are more than emanations representing various factors of Buddha-nature; they also serve as multipurpose containers.

Cultural Diversity in Buddha-Figures

Some Westerners feel that the Buddha-figures are too alien to meet the needs of Western tantra practitioners. They would like modifications in their forms. Before acting hastily, they might benefit from studying the historical precedents.

As tantra practice spread from India to East Asia and Tibet, some of the Buddha-figures indeed altered forms. Most of the changes, however, were minor. For instance, the facial features matched those of the local races and, in the case of China, the clothing, postures, and hairdos corresponded as well. The most radical alteration was with Avalokiteshvara transforming from male to female in Central and East Asia. A traditional Mahayana explanation for the phenomenon is that Buddhas are masters of skillful means and therefore they manifest in different forms to suit varied societies. Chinese associate compassion more comfortably with women than with men. Buddhologists assert that tantric masters made these modifications themselves, using skillful means to adapt the forms to cultural tastes. The Mahayana retort is that the masters received inspiration and guidance for the changes from the Buddha-figures themselves, in pure visions and other revelations. In either case, the point in common is that the Buddhist principle of skillful means requires the modification of forms to suit and thus benefit different cultures.

Despite modifications, certain features of the Buddha-figures remained untouched as tantra spread from one Asian culture to another. The most noticeable one is the retention of multiple limbs.

Moreover, manifold faces and limbs stand for multiple Buddha-nature aspects and realizations along the path. For example, it is difficult to maintain simultaneous mindfulness of twenty-four qualities and realizations in an abstract manner. By representing them graphically with twenty-four arms, it is easier to keep them in mind all at once by visualizing oneself with an array of arms. To eliminate the multilimbed features of the Buddha-figures in order to make visualization of them more comfortable for Westerners would sacrifice this essential facet of tantra practice - the interweaving of sutra themes.

Monotheistic religions, on the other hand, regard themselves as upholders of the exclusive truth. Their leaders would undoubtedly take offense at nontheistic religions such as Buddhism declaring their most sacred figures emanations of Buddha and incorporating them into their practices, particularly into practices involving sexual imagery. One of the bodhisattva vows is to avoid doing anything that would cause others to disparage Buddha's teachings. Adapting Jesus and Mary for tantra self-visualization, then, might harm interfaith relations.

Survey of Misunderstanding

One of the more perplexing and most easily misunderstood aspects of tantra is its imagery suggestive of sex, devil-worship, and violence. Buddha-figures often appear as couples in union and many have demonic faces, stand enveloped in flames, and trample helpless beings beneath their feet. Seeing these images horrified early Western scholars, who often came from Victorian or missionary backgrounds.

Couples in Union

Raising to consciousness and integrating the masculine and feminine principles are important and helpful parts of the path to psychological maturity as taught by several therapeutic schools based on the works of Jung. To ascribe Buddhist tantra as an ancient source of this approach, however, is an interpolation. The misunderstanding comes from seeing Buddha-figures as couples in union and incorrectly translating the Tibetan words for the couple, yab-yum, as male and female. The words actually mean father and mother. Just as a father and mother in union are required for producing a child, likewise method and wisdom in union are required for giving birth to enlightenment.

Method, the father, stands for bodhichitta and various other causes taught in tantra for gaining the enlightening physical bodies of a Buddha or a Buddha's omniscient awareness of conventional truth. Wisdom, the mother, stands for the realization of voidness with various levels of mind, as causes for a Buddha's enlightening mind or a Buddha's omniscient awareness of deepest truth. Gaining the union of a Buddha's physical bodies and mind or a Buddha's omniscient awareness of the conventional and deepest truths of all things requires practicing a union of method and wisdom. Because traditional Indian and Tibetan cultures do not share a Biblical sense of prudishness about sex, they do not have taboos about using sexual imagery to symbolize this union.

One level of meaning of father as method is blissful awareness. The union of father and mother signifies blissful awareness conjoined with the realization of voidness – in other words, the realization or understanding of voidness with a blissful awareness. Here, blissful awareness does not refer to the bliss of orgasmic release as in ordinary sex, but to a blissful state of mind achieved through advanced yoga methods for bringing the energy-winds (lung, rlung; Skt. prana) into the central energy-channel. A prolonged succession of moments of such a mental state is conducive for reaching the subtlest level of the mental continuum, one's clear light continuum – the most efficient level of experiencing for realizing voidness. The embrace of father and mother, then, also symbolizes the blissful aspect of the union of method and wisdom, but in no way signifies the use of ordinary sex as a tantra method.

Peaceful and forceful Deities

Buddha-figures may be peaceful or forceful, as indicated on the simplest level by their having smiles on their faces or fangs bared. More elaborately, forceful figures have terrifying faces, hold an arsenal of weapons, and stand surrounded by flames. Descriptions of them specify in gory detail various ways in which they smash their enemies. Part of the confusion that arises about the role and intent of these forceful figures comes from the usual translations of the word for them, trowo (khro-bo, Skt. kroddha), as angry or wrathful deities.

For many Westerners with a Biblical upbringing, the term wrathful deity carries the connotation of an almighty being with righteous vengeful anger. Such a being metes out divine punishment as retribution for evildoers who have disobeyed its laws or somehow offended it. For some people, a wrathful deity may even connote the Devil or a demon working on the side of darkness. The Buddhist concept has nothing to do with such notions. Although the Tibetan term derives from one of the usual words for anger, anger here has more the connotation of repulsion - a rough state of mind directed toward an object with the wish to get rid of it. Thus, a more appropriate translation for "trowo" might be a forceful figure.

Forceful figures symbolize the strong energetic means often required to break through mental and emotional blocks that prevent one from being clearheaded or compassionate. The enemies the figures smash include dullness, laziness, and self-centeredness. The weapons they use span positive qualities developed along the spiritual path, such as concentration, enthusiasm, and love. The flames that surround them are the different types of deep awareness (yeshey, ye-shes; Skt. jnana, wisdom) that burn away obscurations. Imagining oneself as a forceful figure helps to harness the mental energy and resolve to overcome "internal enemies."

From the Buddhist perspective, the subtlest energy of the clear light continuum may be peaceful or forceful. When associated with confusion, the peaceful and forceful energies and the emotional states that they underlie become destructive. For example, peaceful energy becomes lethargic and forceful energy becomes angry and violent. When rid of confusion, the energies may readily combine with concentration and discriminating awareness (sherab, shes-rab; Skt. prajna, wisdom), so that they are available for positive, constructive use. With peaceful energy, one may calm oneself and others to deal with difficulties in a levelheaded manner. With forceful energy, one may rouse oneself and others to have more strength, courage, and intensity of mind to overcome dangerous situations.