Monastic Funerals (Thailand)

The story of the Buddhafs passing away, his cremation, and the distribution of his relics is vividly presented in the Mahaparinibbana Sutta.a very important text within the early Buddhist canon. According to this very famous account, the Buddhafs passing away, and the funerary process that followed, had at least two crucial components. On the one hand, the events that transpired signaled the Buddhafs attainment of final release from the ongoing process of death and rebirth (that is, his attainment of nirvana). At the same time, the funerary process provided an opportunity for the community to express its respect and to continue to profit from the charisma that his very special spiritual achievements had generated.

Clearly Buddhists have considered the spiritual achievements of the Buddha, and therefore the funerary process that marked his death, to be radically distinctive if not unique. However, many of the practices that have been employed to mark the deaths of members of the Buddhist community.especially the deaths of highly respected senior monks. have displayed practices very similar to those surrounding the Buddhafs passing away. Such funerary practices have incorporated sophisticated ways of recognizing and honoring a life of spiritual attainment and of symbolizing and assisting the rebirth of the deceased in an appropriately positive place and position. They have also provided a process through which the community and its individual members can draw on the spirit

1. Editorsf note: The Shan are a Tai people closely related to the Thai and the Yuan, who live in northern Thailand. The majority of Shan live in the hills of northernMyanmar. 2. Tucao is the northern Thai title for the abbot of a temple. tual capital.the gfield of merith.generated by the deceased through his life of faithful monastic commitment.

In the excerpt that follows, Charles Keyes describes one such funerary process. The senior monk in question, unlike Yeshe Drolma (the nun whose autobiography was recounted in the previous essay), had lived his monastic life in a single monastery, where he had pursued his vocation as abbot and as the spiritual leader within the local community.

Charles F. Keyes

In February 1973 I observed the cremation of an abbot of a village temple near the town of Mae Sariang in northwestern Thailand. During the three days prior to the cremation, which took place on the 9th day of the waxing moon in the 9th lunar month (northern Thai reckoning). that is, on Sunday the 11th of February, the temporary gpalaceh or prasada on which the corpse of the abbot had been placed was pulled to and fro by several hundreds of people. Local people call the funeral of a monk which includes such a ceremonial tug-of-war poi lo, lit. gceremony of the cart or sleigh.h While the people who participated in the ceremony were predominantly northern Thai or Yuan and while the deceased was also northern Thai, the custom of the tug-of-war is said to be of Shan origin.1 In fact, the poi lo ceremony which I observed is closely related to the usual northern Thai funeral for a monk which is known as lak prasat or gpulling of theprasada.

Both thepoi-lo and thelak prasat ceremonies share much with the Burmese rites for a monk known as pongyi byan pwe which Shway Yoe glosses as gthe return of the great glory.h In this paper, I will attempt an explanation of some of the symbolism evident in the poi lo ceremony which I observed in Mae Sariang. Cao Adhikara Candradibya Indavanso Thera or as he was known to local people, Tucao Canthip,2 was born in the village of Nam Dip near the town of Mae Sariang in 1916. After having served as a novice in the local temple, he was ordained at the age of 21 into the monkhood. He remained in the monkhood throughout his life and continued to live in the temple in his home village. While he did not attain any significant scholastic honors awarded by the Thai Sangha, he was locally respected

3. The body of the famous northern Thai monk, Khruba Siwichai, was kept eight years (from 1938 until 1946) before being cremated.

as a knowledgeable practitioner of Yuan or northern Thai Buddhism. For many years before his death, he had been the abbot of the local wat and held the title of cao adhikara which indicates that he was an abbot who was also a thera or monk who has been in the yellow robes for more than ten years. Tucao Canthip passed away, or as it is said, greached the cessation of his natureh on the 23d of November 1972 following a severe attack of dysentery.

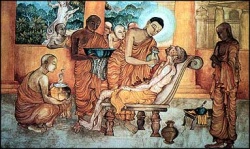

After his death, Tucao Canthipfs body was ritually bathed, dressed in yellowrobes, and placed in a casket which was kept in the temple in which he had lived. In northern Thailand, as in northeastern Thailand and Burma, funerals for ordinary people are held as soon as possible.often within 24 hours.following death. In contrast, the bodies of senior monks (as well as high-ranking lay people) are kept for some months before the cremation is held.3 The District Abbot of Mae Sariang explained that this delay permitted the organizers of the cremation to collect from among the congregation, the clergy, and gBuddhist faithful generallyh the funds necessary for holding an expensive funeral. Sanguan Chotisukkharat, the northern Thai folklorist, has elaborated on this point in a short note on poi lo:

Whenever a Bhikkhu who has been an abbot, has been an important monk of many lenten periods, or has been ordained from youth until his death and has never tasted the pleasure of the world died, it is arranged that his corpse be bathed and placed in a coffin. The corpse is kept several months. This long duration of keeping the corpse permits the faithful to find the money for holding the cremation because it is a major ceremony which requires the expenditure of much money. When enough money has been raised, invitations are sent to Buddhists everywhere and the schedule of merit-making events is made known.

In addition to the need for a period of time in which to raise the necessary funds for funeral expenses, I would add another reason, derived in part from my anthropological perspective, for such a delay between the time of death and the time of cremation. During this period between death and cremation, the deceased is in a state of limbo, having not yet totally departed this world or fully entered the world beyond. This period is characterized by what Victor Turner has called gliminality,h that is, it is a period, ritually marked and invested with complex symbolism, which follows separation from the normal structural roles played by individuals and which occur before a reintegration or aggregation back

into the normal structural world. This process of separation, liminality, and aggregation has long been recognized in studies of rites of passage. However, it has only been with the work of Turner that attention has been focused on liminality. During the liminal period,Turner has shown, the participants are confronted ritually with ambiguity, paradox, and other challenges to the normative basis of social life. Ultimately a new resolution, communicated symbolically in the formof sacred knowledge, is effected, the participants are thus transformed and can be aggregated back into the world.

The death of a monk ushers in a liminal period which differs from that following the death of an ordinary layman. The corpse of an ordinary person is gdangeroush in that the spirit which adheres to the body until cremation may become a malevolent ghost. The continued presence of the corpse of a highly respected monk poses no such threat. By virtue of the merit which such a man has accumulated through rejection of the gpleasures of the world,h his spirit is immune from such a fate after death. Far from being dangerous, the corpse of a monk is auspicious since it becomes a unique gfield of merith for the lay followers and for Sangha brethren.

The coffin containing the corpse of Tucao Canthip was kept in the vihara or image hall of Wat Nam Dip and was placed to the left of the main Buddha image. Not only did the corpse receive offerings of funeral wreaths and of incense, candles, and cut flowers in special rites, but similar offerings were also placed before it on the occasion of every ritual held in the vihara during the period it remained there. Each offering laid before the coffin was believed to produce merit. Serving as a channel of merit was not the only religious function served by the corpse.

More importantly, the corpse served as a constant reminder of a fundamental message of Buddhism.the impermanence of self and the transitoriness of life. Meditation upon corpses is strongly enjoined in the texts of Buddhism and is ritually recognized in Mae Sariang (as elsewhere in northern Thailand) in the ceremony of khao kam.lit., gto enter karma.h In Mae Sariang this ceremony is held for seven days each January during which all the monks and novices of the district go into meditation retreat in the Mae Sariang cemetery. The decaying body also finds representation in pictures which are hung in the buildings of a wat. The corpse of a former monk, whose cremation can be long delayed, is perhaps the best of all symbols in bringing into consciousness reflection about the decay and disintegration of manfs physical form.

Following the death of a monk, a committee is formed to organize the funerary rites, schedule the events for the cremation, and collect the

4. For very important monks, the role of both the local clergy and congregation in organizing the funeral may be considerably reduced. For the funeral of Khruba Siwichai, the feeling that he was spiritual mentor to all of northern Thailand, monk and layman alike, and not only for the local congregation of Wat Ban Pang in Li District, Lamphun province, prevailed. The cremation actually took place at Wat Camthewi near Lamphun City and not at his home temple. The committee which organized the cremation of Phra Upaligunupamacarya, the late abbot of Wat Phra Sing, Chiang Mai, who died in 1973, was headed by the regional ecclesiastical chief, the provincial abbot, the acting abbot of Wat Phra Sing, the governor of Chiang Mai Province, and the senior lay steward of Wat Phra Sing.

Moreover, as this was a cremation at which the king himself brought the fire, much of the planning was removed from the hands of the local community and undertaken by the palace. Indeed, the date of the cremation (which took place on 15 January 1974) was changed several times to accommodate His Majestyfs schedule. money to pay for the costs of the ceremony. For the funeral of Tucao Canthip, the organizing committee was cochaired by the District Abbot, representing the clergy, and the Headman of Ban Nam Dip, representing the laity. The other members of the committee consisted of other members of the Sangha in Mae Sariang and members of the lay stewardship committee of Wat Nam Dip. For ordinary lay people, such an organizing committee includes no representation as such from the Sangha. The death of a member of the Order, however, is not the concern only of his clerical brothers as the equal division between lay and Sangha in the organizing committee for the funeral of Tucao Canthip indicates. Tucao Canthip had been both a member of the Sangha community, which in the small district of Mae Sariang included the clergy of the whole district, and spiritual mentor for the congregation of Wat Nam Dip.4

There appears to be no set length of time which is deemed appropriate or auspicious for keeping the corpse before the cremation. However, certain considerations, which are symbolically significant, influence the choice of time for a cremation. The District Abbot of Mae Sariang said that it was preferable for cremations to be held in the dry season and that they should not be held during lent. All of the cremations of monks in northern Thailand on which I have been able to obtain information occurred between December and March. Shway Yoe also notes for Burma gthat a pongyi byan never takes place during lent.h Lent (called vassa in Pali and phansa in Thai) is the period of rain, of planting, of fertility, of new life as well as the period for retreat for the Sangha. The committee organizing the funeral for Tucao Canthip chose February as the time for the cremation because by that month villagers in Nam Dip would have finished harvesting rice and would not have yet begun planting dry-season crops (which in Nam Dip consist mainly of groundnuts). The field in which the cremation was to be held was filled

5. Editorsf note: Nagas are semidivine beings associated with snakes who play an important role in Buddhist mythology. For more associations, see below. only with the stubble of harvested rice. A Sunday was chosen for the actual day of the burning since it was not a workday for schoolchildren, teachers, and officials. The day chosen for the burning was also purposely not a Buddhist sabbath day (wan phra), that is, a day on which the clergy would have normal ritual duties to perform. In short, the time chosen for the cremation linked the unfertile season in which the fields had only dead rice stalks with the death of a man.

The liminality of the day of burning was underscored by the scheduling of the cremation for a time when both laity and clergy would not have normal functions to carry out. The site chosen for the cremation was not the gcemeteryh where cremations of most lay people are carried out, but was a field belonging to a relative of the late monk. This field lay to the west of WatNam Dip and was on ground which was lower than that on which the wat is located. In the field, several temporary edifices were erected just prior to the beginning of the scheduled events. There were two pavilions. One which faced west was used by the participating monks and the second, at right angles to the first and facing south, was used by a small portion of the laity who attended. Opposite this second pavilion was a stage used for performances of like or Siamese folk opera.

Next to it was amovie screen, hung on bamboo poles. In front of the first pavilion was the gcourseh on which the tug-of-war would be held. Prior to the beginning of the funeral, the prasada without the coffin was placed on this course 15 or 20 meters away from the main pavilion. Later, during the three days of the ceremony, the prasada with the coffin would sit in the same place except when the tugof- war was taking place. Some hundred or so meters away from the pavilions, etc., were four bamboo poles, rising about 20 meters into the air, to which a yellow cloth which had been part of the late monkfs robes was attached.

This construction, called pha phidan or pha phedan, gcloth canopy,h marked the place where the burning would occur. At this point, we should examine the prasada in some detail. The one used in Mae Sariang consisted of an outer structure erected on poles about five meters high with a groof h supported not only by these poles but also by other poles set at diagonals to provide strength. The roof itself consisted of a central tower with five tiers, surrounded by four smaller towers of three tiers each. Each of these towers was crowned by a pole decorated with gflags.h Inside this outer structure was another, again elaborately decorated, which contained the casket. The bottom of the prasada was decorated on both sides with long Naga figures.

6. Editorsf note: In Buddhist cosmology, Meru is the cosmic mountain that constitutes the center and linchpin of the lower realms of the cosmos, including certain heavenly realms as well as the earthly realm in which human beings live. The whole edifice rested upon a sleigh to which heavy ropes had been attached.

In Mae Sariang, the prasada just described served both as the vehicle on which the body was transported to the place of cremation and as the funeral pyre itself. This was rather unusual as in most cremations of monks (and high status laymen) in both Thailand and Burma, hearse and pyre are separate structures. In northern Thailand, the cart used at a funeral of a monk was traditionally in the shape of a hastilinga bird, a mythical creature which has the head, trunk, and tusks of an elephant and the body of a bird. One still sees carts in this shape in some funerals for monks, although the custom has begun to disappear, according to a former District Abbot of Phrao in Chiang Mai province, because the work required to make the animal is too time consuming and too costly.

Few northern Thai whom I have asked know the significance of the hastilinga bird and no one had heard of the ritual killing of the animal which used to occur in northeastern Thailand.Nonetheless, the animal, in its strange combination of elements, must appear to those who see it as disturbing and even dangerous since the creature is not of one class of beings or another. Symbols which cause confusion of normal categories of classification play important roles in liminal periods of rites of passage during which paradox, ambiguity, and bafflement arising from actual experience are confronted and resolved.

In Mae Sariang, the only animal symbol present was the Naga which was represented on the bottom part of the prasada. The Naga has generally been interpreted as a fertility symbol, but it does not have this meaning alone. It also carries a cosmographic meaning, representing the seas which surround Mount Meru.6 The prasada, in turn, represents Meru, a name by which the funerary pyre is also known. The fertility meaning of the Naga does remain, conveying in this context masculine sexuality which has been suppressed when a man enters the Sangha. The juxtaposition of monk and Naga, here manifest in the body of the monk which lies in the coffin above the Naga, recalls other pairings such as the use of the term Naga as the name of the candidate for monkhood and the depictions in sculpture and painting of the Buddhafs conquest of the Naga.

The cremation pyre, whether distinct from the hearse as is normally the case, or combined with it as was the case in the funeral of Tucao Canthip, is recognized by local people as a model of the cosmos. The tiered roofs represent the levels of existence or heavens located on Mount Meru. Through the fire of the cremation, the deceased monkfs earthly model of heaven becomes transformed into actual heaven, that is the abode for the soul of this virtuous man. That monks and highranking laymen are burnt in such elaborate prasada while ordinary people are not symbolizes the belief that those with great merit (evidenced in the wearing of yellowrobes or in possessing power and wealth) will enjoy a heavenly reincarnation.

Thepha phidan or the yellowcloth canopy mounted on bamboo poles at the site of the burning appears to be a uniquely northern Thai custom. It is found only at the cremation of monks or novices and never at the cremation of lay persons, no matter how high-ranking. Sanguan has written that:

these four poles are planted to form a square. A monkfs cloth belonging to the deceased will be stretched as a canopy. . . . [At the burning,] the canopy will be watched to see if it catches fire or not. If the flames burn a hole [in the cloth] this shows that the soul of the virtuous senior monk has departed well . . .

Puangkham Tuikhiao, a former District Abbot of Phrao in Chiang Mai province and in 1973 a research associate in the Faculty of the Social Sciences at Chiang MaiUniversity, says that if the cloth burns, it shows that the monk was gpureh and thus entitled to a high rebirth. If it does not burn, then it indicates that the monk still has gimpuritiesh and must return in a state less than that of heaven. He will still enjoy a better rebirth than ordinary men.

The events scheduled for the cremation of Tucao Canthip began with an gentertainingh form of sermon, a performance of like, and a movie in the evening on Thursday, the 8th of February and ended with the collecting of the remains in the early morning of Monday, the 12th of February. The events scheduled, according both to the printed schedule and to the words of informants, provided the lay people who attended with the opportunity to make merit through presentation of food and alms to the participating Sangha, through listening to sermons, and through the unique opportunity of the tug-of-war over the body of the deceased monk. In addition, those who came could observe the burning and enjoy various entertainments. The clergy, in their turn, made merit by performing their ritual roles in the events. Finally, a small group of monks and laymen gathered a few remains to be kept for later internment in a stupa (a traditional Buddhist burial structure).

7. Editorsf note: Vessantara was the birth of the Buddha before he was born as Gautama. During that birth, Vessantara perfected the virtue of generosity by, among other things, giving his children to the Brahmin Jujaka. The entertainments drew the largest crowds of all events save for the tug-of-war and the burning. In addition to the nightly performance of like and showing of movies, the entertainments also included some of the sermons. On Saturday evening, a well-known monk from Mae Rim near Chiang Mai delivered a two-hour version of the Jujaka story from the Vessantara Jataka.7 For the whole two hours, he had the audience in stitches as he made ribald remarks about the love of the old Brahmin, Jujaka, for a young pretty girl, as he described, with imitations of conversations, how this young girl grew into an avaricious bitch and how Jujaka, constantly plagued by flatulence (noted with appropriate sound effects), strived to do his wifefs bidding.

Such entertainments, which to some Westerners would seem to transgress the boundaries of respect at a funeral, are not as anomalous as they might first seem. gWakes,h which include the playing of games, courting, gambling, and drinking, are found throughout Thailand, Laos, and Burma as part of the activities which take place following a death. Such activities underscore the liminality of the period because they involve watching fantasies (like and movies), interacting in social relationships which do not, in the end, alter any normative structure of everyday life (games), or entrance into states which are temporary (drunkenness, courtship). The funeral afforded those laymen who chose to do so with several conventional ways to acquire merit.

One way was to contribute to the costs of the funeral. In the announcement of the events scheduled for the cremation of Tucao Canthip, the presentation of the mid-day meal for the participating clergy on each of the three main days and the presentation of alms to the Sangha were specifically listed. The amount involved was not small since 56 monks (a number equal to the age of the late abbot) and four novices had been invited from various villages and towns in Mae Hong Son province. Thus, the announcement requested that gif anyone should wish to be a donor of alms . . . please contact or make your reservations with the committee.h Donors were asked to contribute 100 baht each. The greatest expense involved, that of the construction of the various edifices, was met through the merit-making donations of the villagers from Ban Nam Dip. These donations also paid for the costs of the bangsakun robes which are an essential alms-offering to clergy at cremations. In addition to gaining merit through gifts to the clergy, lay people could also gain merit through listening to the sermons

8. Editorsf note: Karen are a non-Tai ethnic group that forms a significant segment of the population in the Mae Sariang area.

delivered. With the exception of the sermon concerning Jujaka, mentioned above, the sermons (which were read from Yuan texts) attracted only older people. Although these conventional ways of making merit were far from unimportant, it seems clear that the merit-making activity which attracted the greatest number of people was the tug-of-war. After the body in its coffin had been moved from the temple to be placed in the prasada on Friday, the first tug-of-war took place. On each afternoon of the next two days, a similar event occurred, lasting several hours on each occasion. The prasada was oriented in an East-West direction in the middle of the field.

The heavy ropes attached to each side of the sleigh were picked up by men and dragged in opposite directions. Then men, women, and children.mainly northern Thai but with some Karen and Shan as well.took hold of the ropes on either side.8 There was no special social basis for determining who chose to go on one side rather than the other and I observed many who changed sides. A number of men and even a few women had appointed themselves as coaches cum cheerleaders; several even had megaphones. These people encouraged the side they were on to begin pulling. Usually the side that began would have the advantage, but would be stopped finally as more and more people joined the other side. Sometimes the rope broke and the side having the good rope might pull the prasada several dozen meters before they were persuaded to stop.

Flags marked the course on which the tug-of-war took place, but there were no ggoals,h no points which if the prasada passed, one side could claim a victory. To my question as to why the people engaged in this apparently inconclusive competition over the corpse of a monk, I received invariably the same answer: those who participate gain great merit. The same point was emphasized in the mimeographed announcement of events which concluded: gwe invite all faithful and good people to join in the meritmaking at the cremation of Cao Adhikhara Canthip by contributing strength and spirit in the tug-of-war of the prasada which is the local custom. [By doing so,] we believe that we gain great merit.h Shway Yoe gives a similar explanation for the same ritual action in Burma, although he said that the merit gfalls to the share of those who win in the tug-ofwar.h In Mae Sariang, no distinction was made between those who participated on one side as distinct from the other. Sanguan, the northern Thai folklorist, has elaborated upon the theme that participation in the tug-of-war brings great merit:

9. It should be noted that in usual northern Thai funerals for monks, the prasada is pulled in procession for a considerable distance before being taken to the place of cremation. In the most important cremation of a monk in modern history, that of Khruba Siwichai in 1946, the body was carried in procession from the village of Ban Pang in Li District, Lamphun, to near Lamphun City, a distance of about 80 kilometers. Poi lo . . . is the supreme merit-making [[[Wikipedia:ceremony|ceremony]]] because it is believed that anyone who dies in the yellow robes, having dedicated his life to the religion, has much merit. The funerary merit-making for such a monk, it is believed, will yield strong merit. Thus, merit-making should be undertaken without concern for the expense.

The tug-of-war, in contrast to simply pulling the prasada directly to the place of burning, serves to prolong the tapping of merit possessed by the late monk.9 The purpose of the competition is not for one side or the other to obtain more merit, but to draw out as much merit through pulling the prasada to and fro. Inherent in this act is the belief, widely held in Theravada Buddhist societies, that one who possesses great merit .e.g., a highly esteemed monk.can share this merit, and the benefits following from such merit, with others who act in appropriate ways. The transfer of merit through the pulling of the corpse is not the only meaning of the tug-of-war. As noted above, the course for the tug-ofwar was oriented in an East-West direction, with the site of the cremation being located to the West. The West is recognized by Mae Sariang people, as by most Southeast Asians, as the way of the dead, while the East is associated with birth and auspiciousness. The movement, then, from East to West, back again, and so on, clearly symbolizes the cycle of birth, death, rebirth, etc.

The resolution of the tug-of-war was in keeping with the above meaning for eventually the contest ended when the prasada was pulled to the site of the cremation which laid to the West. In the late afternoon on Sunday, the District Abbot gave a signal to end the tug-of-war and to begin the burning. Everyone then shifted to the western end of the prasada and helped in pulling the edifice to the place under the pha phidan where the actual cremation would take place. Once there, several men began to pile dried logs around the coffin inside the outer structure of the prasada. Next, members of the lay committee placed packages containing clerical robes on the pyre. These were the bangsakun robes which are symbolic reminders of Buddhafs enjoinder to the monks that they should use discarded shrouds for their robes. After the monks had claimed their cloths, several laymen poured gasoline on the firewood. Next, an elaborate fireworks system was set off; this involved the light

10. These stupas are located at Wat Ban Pang, Khruba Siwichaifs home temple in Li District, Lamphun province, atWat Cam Thewi in Muang District, Lamphun, atWat Suan Dok in Muang District, Chiang Mai province, and at Wat Doi Ngam in Sankamphaeng District, Chiang Mai.

ing of rockets which travelled along wires to lantern-shaped containers of gunpowder which when ignited set off yet another rocket. The final rocket plunged into the pyre itself. Yet other rockets were set off along the ground towards the pyre; it was one of these which actually started the burning.

The pyre burned rapidly and people watched the burning for only a few minutes before turning to go home. Before departing, it was apparent to all that the pha phidan was not going to catch fire. A few laymen from the local congregation stayed to see that the flames consumed all the prasada and the body contained therein. On the following morning, a few men from the local congregation, the monks and novices from the local temple, and a few of the late abbotfs relatives foregathered at the site of the cremation. They collected some of the remains of the abbotfs burnt bones. These would later be enshrined in a small stupa called a ku in northern Thailand, in the grounds of the wat. While in the case of the late abbot of Wat Nam Dip one would not expect this stupa to have any great significance, some such stupas become the focus of cults.

This is the case of the four stupas which contain the relics of the famous northern Thai monk, Khruba Siwichai,10 and, in Mae Sariang, of the stupa containing the remains of the late abbot of Wat Phapha. This latter monk had been renowned for his holiness and supernatural powers during his life and his cremation was still talked about for the auspicious omen which had occurred at it. A circle had appeared in the middle of the pha phidan for which no natural explanation could be given. In the case of this monk, as in the case of Khruba Siwichai, people believe that their great merit has not been exhausted at the cremation and can still be tapped.

Death transforms the monk not into a threat to the aspects of life most valued but into a vehicle whereby the good life can be achieved both by himself and by others. For himself, it is believed that the monk will not be reborn into a more holy state, but will be reborn in heaven where earthly pleasures can be enjoyed without the suffering which accompanies such pleasure in this world. Herein lies the meaning of the prasada, whose burning together with the body transforms the monk into a denizen of heaven. Moreover, the monkfs great merit which ensures him of a good rebirth can be shared with those who assist in pulling his body to the place of burning. Such is the meaning, in part, of the tugof- war.

Although death is conceived of as auspicious in the case of a monk, it cannot be denied, even in the funeral for a monk, as an ultimate concern. Indeed, shorn of more proximate challenges posed to structure by the death of an ordinary person, the death of a monk becomes the occasion, in the funeral rites which follow, for a clear confrontation with this ultimate concern. The dissolution of self and decay of the body are kept before the eyes of the local people during the long period that the body is kept before the cremation. Again, the choice of the time and place for the cremation reemphasizes the negative side of death. And for all the decoration and elaborate construction, there is no question in anybodyfs mind but that the prasada contains a corpse.

This awareness of death is met by symbolic answers to the question of what death means. These answers are supremely Buddhist. Man is born to die and dies to be reborn once again. Such is the fundamental meaning of the tug-of-war. It is also the meaning of the act of burning which effects the transformation between death and rebirth. While in the case of the monk, this rebirth will be a pleasurable one.how pleasurable being known by whether the pha phidan burns or not.it will not be the final one. With the exceptions of arahans (renunciatory saints), the likes of whom have not been seen in the world for a long time, monks, like ordinary laymen, have not exhausted their karma at death. Thus, they too will be reborn. And here we return again to the symbolism of the tug-of-war which can be seen as competition between death and life in which there is no ultimate champion. That champion is neither death nor life; but for an understanding of this Buddhist conception it is necessary to go beyond the symbols found in death rites.

Those who attended the cremation of Tucao Canthip came away with a sense of well-being, albeit a few had this sense diluted by hangovers. The sense of well-being was in part a consequence of having gained merit through participation in the tug-of-war. Itwas also, in part, a consequence of an experience of gcommunitash during the tug-of-war and in the entertainments during which social differences were irrelevant. In addition, the power of the symbols of the ritual etched on most minds some idea of the meaning of death. If this meaning were to be reflected upon.and admittedly it is only by a very few.it would be found to be not wholly satisfactory. It is for this reason that Buddhist theology is not confined to ritual symbols alone; deeper understandings come though study and meditation.