More on the Svātantrika-Prāsaṅgika Difference: Madhyamaka and Buddhist Epistemology

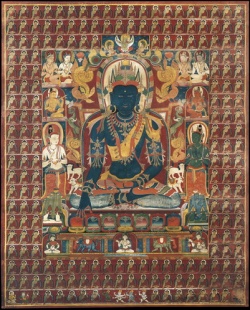

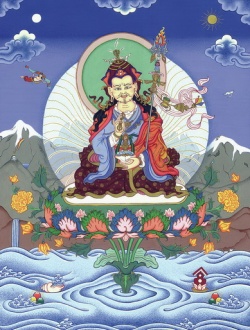

Madhyamaka, or "Middle Way," philosophy came to Tibet from India and became the basis of all of Tibetan Buddhism. The Tibetans, however, differentiated two streams of Madhyamaka philosophy--Svatantrika and Prasangika

As indicated, the so-called Svātantrika trajectory of Madhyamaka constitutively involves recourse to the tools of formal logic and inference, evincing a characteristic concern to restate Nāgārjuna’s arguments as formally valid inferences. More generally, it can be said that this approach is informed by Bhāvaviveka’s use of the logic and epistemology of Dignāga (c. 480-540), who influentially appealed to the idiom of pramāṇavidyā (the “discipline of logic and epistemology”) in advancing the Buddhist position – and who was, indeed, among the most important figures in developing the broadly Sanskritic conceptual vocabulary that would predominate in the subsequent course of Indian philosophy. Similarly, such later Svātantrikas as Śāntarakṣita were informed by the project of Dignāga’s influential expositor Dharmakīrti (c. 600-660), and figures such as Dharmakīrti and Śāntarakṣita would be of decisive importance for the remaining course of the Indian Buddhist philosophical tradition’s life. (Candrakīrti, in contrast, would exercise little influence in India, though he re-emerges with the Tibetan tradition’s interest in him.)

The dispute between these lines of interpretation crystallizes around the figures of Buddhapālita, Bhāvaviveka, and Candrakīrti – and can be seen, in particular, in their respective elaborations of Nāgārjuna’s MMK 1.1 (“There do not exist, anywhere at all, any existents whatsoever, arisen either from themselves or from something else, either from both or altogether without cause”). This verse basically deploys a standard tool in the Mādhyamika arsenal: the “tetralemma” (catuṣkoṭi), a four-fold statement that is meant to identify all possible relations between any category and its putative explananda (e.g., “the same,” “different,” “both the same and different,” “neither the same nor different”) – with the standard Mādhyamika denial of all four horns of the tetralemma meant as an exhaustive refutation of the efficacy and coherence of the category in question. (One modern interpretive discussion concerns whether or not this apparent violation of bivalent logic shows Mādhyamikas to have presupposed a non-standard sort of logic.)

Buddhapālita’s “prāsaṅgika” commentary on this verse does nothing more than make clear (what he takes to be) the absurd consequences that would be entailed by affirming any one of the positions here rejected. For example, the view that existents originate intrinsically – a position traditionally understood to express the Indian Sāṃkhya school’s characteristic view that effects are always latent within their causes – is to be denied “since there would be no point in the arising of already existent things.” That is, an affirmation of the causation of something from itself entails that the thing in question already exists, in which case, its coming-into-being could not be thought to require causal explanation.

In his commentary on the MMK, Bhāvaviveka then specifically took Buddhapālita to task, urging that Buddhapālita’s elaboration of the argument was unreasonable “because no reason and no example are given and because faults stated by the opponent are not answered” – which is to say, because the recognized terms of a formally stated inference (as that had been thematized by Sanskritic philosophers such as Dignāga) were not present. In contrast, then, to Buddhapālita, Bhāvaviveka offers a formally valid statement of the reasoning behind Nāgārjuna’s denial of the first horn of the verse’s tetralemma: “[[[Wikipedia:Thesis|Thesis]]:] It is certain that the inner sense fields (āyatanas) do not ultimately originate from themselves; (Reason:] because they exist [already], [Example:] like consciousness.” Among the characteristic features of Bhāvaviveka’s restatement here is his making explicit the qualifier “ultimately” (or “essentially,” svabhāvataḥ); that is, Nāgārjuna is here said to deny only that something is the case essentially or ultimately. While the first horn of this tetralemma (“existents are arisen from themselves”) perhaps requires no such qualification in order for its denial to be intelligible, many interpreters would agree that such a qualification must be added particularly in order for the denial of the second (which concerns that origination of things from other existents) to make any sense; for it is surely counter-intuitive to think that we cannot even conventionally speak of the origination of existents from one another. A great many of Nāgārjuna’s prima facie counter-intuitive refutations can be understood to make more sense if they are qualified as concerning what is “ultimately” or “essentially” the case (and not taken simpliciter).

A considerable portion of the first chapter of Candrakīrti’s Prasannapadā is then given over to defending Buddhapālita’s as the right way to proceed, and to criticizing Bhāvaviveka’s interpretive procedure as misguided. How, then, are we to make sense, without Bhāvaviveka’s characteristic qualification, of Nāgārjuna’s denial of the second horn of the tetralemma – of his denial, that is, that things originate from other existents? On Candrakīrti’s reading (which follows Buddhapālita’s), the absurdity that would be entailed by thinking otherwise would be that a sprout could just as well be produced from the coals of a fire as from a seed; and, conversely, if a sprout cannot be produced from the coals of a fire, it cannot be said to be produced from a seed, either. Candrakīrti’s argument here is usefully understood as involving a priori (as contra a posteriori) analysis; that is, the argument short-circuits any appeal to what we experience to be the case, instead analyzing only the concepts presupposed in how we explain experience – and the point is to reduce to absurdity any argument that presupposes the independence of such concepts (that presupposes, in other words, that any such concepts might afford a privileged perspective on what there is). Read this way, the argument turns simply on the definition of “other,” and the point is that the general concept of “otherness” leaves us with no principled way to know which other things are relevantly connected to the thing whose arising we seek to explain, and we are left to suppose that anything that is “other” than the latter (even the coals of a fire) could give rise to it.

Although many Tibetan exegetes were (as noted) inclined to see the dispute here as turning on subtle ontological presuppositions, this can be hard to glean from the Indian texts upon which the dispute is based. The characteristically Svātantrika appeal to the idiom of logic and epistemology can, however, be understood as meant to address what are real philosophical problems in the Mādhyamika project as that is understood by Candrakīrti – just as Candrakīrti, for his part, can be understood as having philosophically principled reasons for refusing the epistemological tools characteristically deployed by Bhāvaviveka and his heirs. What is at issue here is, once again, the question of how we are to regard the “conventionally” described world once the idea that there can be an “ultimately” true description thereof has been jettisoned. Nāgārjuna himself had emphasized the importance of some kind of relation in this regard, saying, for example, that “without relying on convention, the ultimate is not taught; without having understood the ultimate, nirvāṇa is not apprehended” (MMK 24.10). In other words, the (relative) reality of the conventionally described world is a condition of the possibility of our coming to understand what is ultimately the case; but if what is understood thereby is in fact that there is nothing “more real” than the conventionally described world – that, e.g., there are no ontological primitives that are not themselves subject to the conditions that obtain in the world – then it might be thought that, as it were, “anything goes.”

The philosophical worry, then, is that if Mādhyamika arguments are not understood in something like the way that Svātantrikas propose, Madhyamaka could degenerate into a thoroughgoing and pernicious conventionalism. The broadly Svātantrika line of interpretation attempts to address this worry by arguing that even if all discourse (including that of the Mādhyamika) perforce takes place at the “conventional” level, it is nevertheless the case that some “conventions” are more nearly true than others – and that the epistemological tools developed by Dignāga and Dharmakīrti give us the resources to sort these out. The Svātantrika Jñānagarbha (followed, in this regard, by his student Śāntarakṣita) emphasized that we can distinguish between “true convention” (tathya-saṃvṛti) and “false convention” (mithyā-saṃvṛti).

In his refusal of the characteristically “Svātantrika” use of the conceptual tools of Buddhist epistemology, Candrakīrti need not be understood as conceding simply that anything goes. Candrakīrti’s point, rather, would seem to be to emphasize that there can be no explanatory categories that do not themselves exhibit the same characteristics (chiefly, the fact of being dependently originated) already on display in the conventionally described world; and any constitutively analytic sort of reasoning (such as that exemplified by the discourse of epistemology) just is a search for something beyond what is already given in conventional discourse. What is “conventionally” true, then, is (by definition) just our conventions – and any demand for some account or explanation of these could be thought to provide some purchase only to the extent that what is demanded is something that is not itself “conventional.” But there cannot be any such discourse, any more than there can be an existent that is not dependently originated; the two claims are related insofar as all that could count as a discursively exhaustive explanation would be one that adduces something that is not itself subject to the constraints that it explains – which is to say, something not dependently originated. Although this may represent an adequate reconstruction of his position, Candrakīrti’s emphasis on the definitively “non-analytic” character of conventional discourse can, nevertheless, reasonably be thought to leave his project vulnerable to charges of incoherence, and it can be seen that the issues in dispute between Svātantrikas and Prāsaṅgika are the same paradoxes that bedevil Madhyamaka more generally.