Mythical Ancestors

By Sallie Tisdale

The Buddhist canon in its entirety fills hundreds of volumes. Much of this is taken up by sutras, which traditionally means the words of a buddha, a fully enlightened being. Many of the sutras are short, simple stories or lectures, often called discourses, told by the historical buddha to his followers. They arose from an oral tradition and were used to expound and explain the teaching. Sutras are intended to invoke awe and faith as well as understanding, to comfort and instruct, to affirm and inspire. Buddhist belief includes the existence of uncountable buddhas in uncountable buddha realms, both before and after this particular world and its buddha, and some of the great sutras take place in this universe. An extraordinary ease with unbounded space and time marks many of these sutras, which may be the most blissful and miraculous of all religious literature.

Sutras are marked by particular qualities, though within those qualities they vary a great deal. The language of the sutras is formal. Some are funny, and most are filled with deliberate (and sometimes mind-boggling) repetition. The central concern is always the nature of enlightenment itself. Most include lessons or lists, some are oral histories of debates and events, and some use archetypal and mythical imagery, including the kind of everyday miracles common to religious myth. Certain characters appear again and again, fulfilling particular roles. Sariputra is often presented as a dull fellow who needs to be instructed repeatedly in order to understand the teaching. Mañjusri represents wisdom. Ananda sometimes speaks for the Buddha, in his role as living memory.

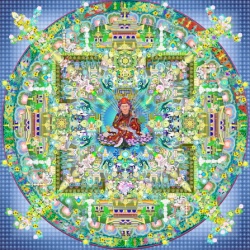

The blurred boundaries of concrete reality and the world of the formless fill and define the great Mahayana sutras, which describe a universe of flexible time and space. The Buddha easily appears in multiple worlds, in many places and times, sometimes in many worlds at once. He walks in the air, levitates his audience, builds temples in the sky, or transforms the environment in order to make a point. Flowers rain from the heavens; music fills the world. There is little or no barrier between the human world and the worlds occupied by other beings, such as dragons, demons, gods, and bodhisattvas. The characters in sutras move readily from form to form, life to life, world to world, appearing in each other's places and times effortlessly. Their names evoke great qualities -- Energetic Power, Lion's Foot, Diamond Matrix, Forest of Virtues. Prophecies are made, predictions fulfilled, and the merit of many lifetimes comes to fruit.

In such a malleable literature, Maya, whose story is told in several places, including the very long Avatamsaka Sutra, is able to die in the human world and later appear elsewhere, in the world of the gods. (The Avatamsaka Sutra is so long and repetitious that its main stories are collected in a separate appended chapter, the "Entry into the Realm of Reality," for ease of reading. It is from this section that I've taken the latter part of Maya's story, as well as that of Prabhuta, found elsewhere in the world of the gods.)

The dragon people, or Nagas, appear in many stories throughout the Buddhist canon. The Buddha preached a very brief sutra to them, in which he says that theirs is a rebirth of extraordinary beauty. The Naga princess, who has no name but whose story is famously told in the Lotus Sutra, demonstrates the ease with which a wise being can transform from shape to shape. Her story has been interpreted in more than one way over the years. My own interpretation is based in a careful reading not only of the short section in which she appears but of the Lotus Sutra itself, which is devoted to the universality of enlightenment.

Another woman of the Naga realms appears in the Sutra of Sagara, the Naga King, also called the Ocean Dragon King Sutra. (The sutras are deeply interrelated, and so are their characters. King Sagara is the father of the nameless princess.) Another dragon woman, known by the name Silk Brocade and other titles, meets the Buddha in this sutra when he travels to the dragon's kingdom beneath the sea.

Queen Shrimala is a figure we know little of these days, but whose lectures and miraculous meeting with the Buddha were well known in historical Buddhist China and Japan. Her story, the Srimaladevisim-hanadasutram, or the Lion's Roar of Queen Srimala, at last available in English (from Tibetan and Chinese translations), was widely read and lectured upon historically, but today it is little studied. I think this is unfortunate, and not only because in her short but challenging tale the Buddha insists that the story be kept alive. It begins, like many sutras, with Ananda's memory: "Thus have I heard," says Ananda. "The Buddha commanded that Kausika and I keep this story alive, telling it again and again, sharing it with all the gods and people of all forms."

The following stories are taken directly from the sutras but are cast in my own words. Those familiar with these sutras will notice that some of the repetition, especially the repetition of cosmic and miraculous images, is missing, as a concession to the storytelling and the modern reader. The context of time and place is added in some cases. There is no substitute for the original, of course.