On Younghusband, the Last Great Imperial Adventurer by Patrick French

For years, I have been longing to write a reaction to the book entitled Younghusband, the Last Great Imperial Adventurer.

Patrick French, the author of this book, is not a Tibetologist but in 1994, Harper Collins published his book Younghusband, the Last Great Imperial Adventurer. Soon after that, two different Chinese translations came out-both in China and overseas (Zheng Minghua is the translator of the former, very slightly abridged into one volume, and Xinjiang People's Publishing House,2000, Urumqi). In 1999, Marco Polo Cultural Career Stock Ltd. published the second version in two volumes.

This book is Younghusband's biography, not a travelogue, but who is this person? Readers who know something of the modern history of Tibet will probably know that he was an active participant in the British imperialist invasion of Tibet in modern times; a killer of many Tibetans and a chief of the British troops who conducted burning, killing and looting on their way to conquer Lhasa. If you are to write something about the modern history of Tibet, you have to mention Younghusband. French says in his book that it was Tibet that inspired him to write about Younghusband. The major contents of this book are centered on the British invasion of Tibet in 1904. Younghusband's experience and his activities, as described in this book, will be a great help for us to achieve an understanding of the causes and background to that war.

According to the Chinese translation (Xinjiang People's Publishing House, 2000), the chapter headings are as follows:

Part I:1) Younghusband:"Damned Rum Name"2), Two Journeys to the Mountains,3)Playing Great Games beyond Manchuria,4) Across the Gobi and Down the Mustagh,5) "Impressed by My Bearing", Bearding the Mir, 6) That Sinkiang Feeling: Outwitted in High Asia, 7) Loving a Splendid Colonel and Seeking God's Kingdom, 8) Clubland: Travels with a Most Superior Person, 9) "Not only a Fiasco":African Intrigue.

Part II: 10) An Interlude in Rajputana, 11) "A Really Magnificent Business", 12) The Sikkim Adventure, 13) Sixty-seven Shirts, A Bath and an Army, 14) "The Empire Cannot Be Run like a Tea Party", 15) "Bolting like Rabbits": Blood in the Land of Snows, 16) "Helpless as if the Sky Had Hit the Earth", 17) Fame in Disgrace and Diversion in Kashmir.

Part III: 18) Playing Politics, Brushing Death, Preaching Atheism, 19) Fighting for Right in the Great War, 20) The Quest for a World Leader on the Planet Altair, 21) Running the Jog and Climbing Mount Everest, 22) Religious Dramas, Peculiar Swamis and Indian Sages, 23) The Remains of His Day: Inventing Societies, 24) Love in the Blitz.

Epilogue: Creating the God-Child

Obviously, Part Two is the focus and the major content of the whole book as well. Younghusband reached the peak of his career in 1904 when he led the British expedition to invade Tibet. However, there were reasons for Curzon, the British viceroy of India, to choose Younghusband for this task.

Francis Younghusband was born in India in 1863. His grandfather, father and uncle had served the British Empire during its colonial expansion in the East. His father participated in military actions to suppress the uprisings launched by the Indians in 1857. At the age of 20, Younghusband was sent back to Britain to study in the newly established Clifton College. This college aimed at fostering a group of "talents who are able to administer the British Empire" and "will never withdraw in the wars of extending territories. They will possess the ability to administer colonies of several thousand-square-metres using only martial music and rattan sticks". After graduation, Younghusband returned to India and joined the army. At that time, the race between Great Britain and Russia for colonies in the central regions of Asia (later called the Great Game) was just unfolding. Younghusband was determined to display his skill in this race. In 1886, he sneaked into the northeast of China alone and then traveled westward. He crossed the broad Mongolian plateau and vast Gobi Desert in Xinjiang and climbed over the Karakorum Mountain before he returned to India via Kashimir. His travels in China gained him considerable fame. When the first British invasion of Tibet started, he already had the ambition to enter Tibet alone. In his opinion, Tibet was not only the last broad, mysterious area unexploited by the West, but also a chess piece missing from the British imperial chessboard. The period from the late 19th century to the early 20th century was the last period in which Western big powers conducted crazy colonial adventures. Travel books concerning far and exotic countries were the most popular readings in the West. The mystery of Tibet even drove some Western writers to fabricate books about expeditions there. Though only 20 years old, Younghusband offered a suggestion to the British-Indian Government that he would like to disguise himself as a merchant so as to enter Lhasa, Tibet for research. However, his dream of entering Lhasa really came true only after Curzon came into power in India.

Curzon, the British viceroy of India, was the planner of the second British invasion of Tibet in 1904. He acted as the viceroy in 1899 when he was only 39, younger and more ambitious than any of his precursors. As early as 1892, Curzon, then Vice-Minister of State in the Indian Office of the British Government, got acquainted with Younghusband in London. Two years later, they traveled together in Central Asia. At that time, Russia was extending its territories in Asia, directing its spearhead against the northern border of British-India and exerting its influence there. Led by such Czarist military officers as Nikolay M.Prejevalski and Grombtchevski, the "expeditions" took Tibet as their target, repeatedly entering the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau of China. Just as Friedrich Engels pointed out as early as 1858, Russia "will knock at the door of India1". The Czar's ambitions towards Tibet made a group of British officials in the colonies feel uneasy. Upon taking up the official post, Curzon actively pushed forward the "policy of advancement" in an attempt to expand British influence in Tibet before the Russians made a claim. This is the background of the British invasion of Tibet in 1904. In the process of planning, Curzon realized that no one but Younghusband was more suitable for this.

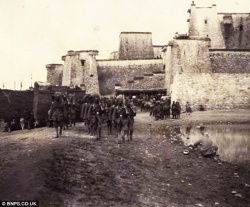

However, in the early 20th century, having witnessed the Yihetuan Movement (the Boxer rebellion, an anti-imperialist armed struggle in 1900), the big powers basically accepted an "open-door" policy on China as suggested by the U.S Government. They did not want to provoke the Chinese people to rise against imperialist invasions by appearing to be subjugating their nation, and they hoped to avoid open fights between the big powers involved in seizing China. Any of the big powers who had the intention to invade China had to give a reasonable excuse. The second British invasion of Tibet borrowed an open pretence that a British Mission would be sent to Tibet to discuss affairs on borders and trades. So the aggressor's troops served as an escort to go with the "Mission" into Tibet and Younghusband acted as its head. The Mission needed an escort, because Tibetan authorities were unwilling to receive this mission and to deal with the British-Indian Government who ruled India and then controlled Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim. So from the very beginning, Curzon, Younghusband and their parties were ready to take Lhasa by force.

From the Qing Emperor Qianlong's reign on, Qing Governments had sent Ambans (residential officer in Tibet) and troops to be stationed in Tibet. However, in the early 20th century, the Qing Government's days were numbered so it dared not fight against the British to safeguard its territories. Thus, there emerged an absurd situation: the just actions taken by the local government of Tibet to attack the armed invasion launched by the British imperialists were regarded as a violation of the decrees issued by the Qing emperor. No matter how the Qing Court betrayed and harmed its country, brave Tibetans fought dauntlessly against the invaders. Interested parties kept records about this war, and some Western scholars also made specific studies of it. French mentions the old stories in his book for he had read some new material, had made some new discoveries and with new knowledge he drew a new conclusion. The following is the most distinctive example.

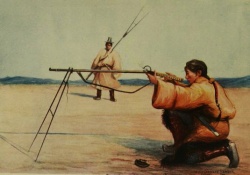

After the British troops entered Tibet, the first war broke out in Chumigshango Valley between present Phag-ri and Khang-dmar. In March of 1904, Tibetan troops were ordered to build up stonewalls in advance on a vast expanse of land so as to stop the further invasion of the British troops. Lha-ding (lha-sding) mDavdpon, general of the Tibetan troops, was ordered to reason with the British, but not to shoot first. Facing the battlefield, Younghasband gave an order to the British troops to aim at Tibetan troops with their machine guns and arrange their cannons on the hill along the rear flank occupied by Tibetan troops. And then, Younghusband suggested that, in order to show the sincerity from both sides, the British troops remove cartridges from their rifles and Tibetan troops put out matches in their matchlocks. Tibetan troops, knowing nothing about armed invaders, did not realize that the time was absolutely not the same for them to relight the matches and for the British troops to get their rifles loaded. And at that point, the British invaders, taking advantage of their knowledge that the Tibetan troops would not shoot first, pressed on towards the stonewalls, and, separated by the walls, they confronted the Tibetan troops. Then, Younghusband gave the order to take in weapons from the Tibetan troops. As a result, the war broke out. In a few minutes, several hundreds of Tibetans were killed under the gunfire, and only a few British invaders were dead. The news reached Britain, where some persons from the political circle considered it a slaughter. Some survivors gave their accounts, so some records are kept in Chinese historical materials. However, Westerners knew little about it for Younghusband concealed the truth in his book2. According to him, it was Lha-ding vDav-dpon and Tibetan troops who shot first. Facing censure from the British, Younghusband tried to evade his responsibility by telling lies. Nevertheless, French found that the early report from the British troops did not mention a single word about Younghusband's claim. French, though careful enough, is probably the first Western scholar to have found that Younghusband is a liar and o raise the question of "Who is the chief criminal?" After detailed textual research and analysis, he believed that the British troops shot first. The claim that Lha-ding vDav-dpon shot first was a fabrication after the event. Thus, Younghusband's cruel and hypocritical stance was revealed.

In order to deceive the whole world, Younghusband's book never mentioned the looting conducted by the British in Tibet. French tells us that the British troops indeed played the roles of robbers. Their targets were monasteries for they believed that monasteries kept gold and gems according to legends. Therefore, gates of monasteries were broken and all valuable objects were removed. Gilt statues of Buddha were cut apart one by one and the British troops searched all bodies of the statues. In a meeting to divide the spoils, the British military officers worked out a plan. Younghusband was the head of the Mission, but he did not want to fall behind the others. In his letter to his family, he revealed: "There has been a committee today distributing brass images and things found in the fort. I have been allotted twelve things." In several months, copper statues of Buddha, silver containers, carpets, Tangkas (painted scrolls), embroidery silk robes, ritual trumpets, armors and jewels were sent back to India.

The last part of this book introduces Younghusband's life after he left Tibet. At the end of 1904, he returned to London from British-India on a cold, rainy afternoon. At the railway station, he received a warm welcome from people of all walks of life. In the early 20th century, colonial thinking was prevalent in Britain, so Younghusband became a hero in the minds of colonists. A journalist reported: "The man of glory was attended by friends who were pressed together in the coach. His clean and tidy clothes, bright piercing eyes and resolute and steadfast chin show his strong personality expressed in the process of marching into Tibet." In a period afterward, letters asking for his signatures and photos came from America, Russia, Australia and European countries. Sven Hedin, a Swedish adventurer, presented his compliments to Younghusband, and Younghusband's former lover also wrote letters to him. King Edward VII received him in the Buckingham Palace, promising that the national flag that Younghusband had carried with him upon his entry into Tibet with his Mission would "by order" hang above the portrait of Queen Victoria in the Central Hall in Windsor Castle3. However, after praising and encouraging him, the King was reluctant to express his regret for the divergence between him and the government.

The British Government made the decision to send the Mission to Tibet, but in fact, it basically took a negative attitude toward the results that Youngusband gained in the invasion of Tibet. It was especially discontented with him. For in the whole process, Younghusband had only followed Curzon's orders. He agreed with the instructions from the government outwardly but disagreed them inwardly or neglected them. Early at the end of 1903, the British Government was reluctant to launch an expedition, for it would gain little other than cause criticism from other big powers. So it made a promise to them-especially Russia, its opponent in the "Great Game"-that the Mission sent to Tibet was just a purely temporary action. However, after receiving the telegram about the Lhasa Treaty, it realized that Younghusband had obviously made the event serious by intention. Thus, the British Government sent a telegram to him, asking him to stay there and revise the articles. But Younghusband, undaunted and reckless, tried to find an excuse to leave and ignored the instructions from the British Government. As a result, the British Government had to find other ways to deal with the matter after the event. Frederic, minister of the Indian Office, was discontented with Curzon's arrogance and bossiness in India, worrying that Curzon would become a dominant force. Being Curzon's schoolmate in Eton, Younghusband was considered as Curzon's partner. Therefore, as Curzon's scapegoat, he became a victim of contradictions and conflicts on principles and policies regarding the invasion of Tibet between the Indian Office in London and the British-Indian Government in Simla.

First of all, the British Government humiliated Younghusband in awarding him decorations. At first, the Government even intended to confer upon him a junior title of Knight Commander (only for Indian officials) instead of the title of Baron. In order to appease public opinion, King Edward VII conferred upon him the title of Baron. As the head of the Mission, Younghusband led the aggressor troops to invade Lhasa by burning, killing and looting all the way. He thought that he performed so many deeds of valor in the wars that he could be rewarded according to his deserts and he could get his wife and children rewarded by a title. He had never expected to cause offence to the Government by being so ambitious in the invasion of Tibet, following Curzon so closely, and being more concerned for the interests for India than the global interests of the British Empire.

In August of 1905, Curzon officially resigned as the British viceroy of India. Only Younghusband wrote a letter to praise his schoolmate and superior, expressing his discontent with the treatment to Curzon. He said:” I know that through all my life I shall regard it as my greatest honor that I was privileged to serve under your orders in one really great enterprise. The confidence you placed in me at its commencement and all through its execution, and the gratitude you showed me at its conclusion...have left an impression on me which will never fade."4

This book tells readers that signing the Convention between Great Britain and Russia in August of 1907 made Younghusband very angry, and even caused him to lash-out at the British political system. The articles in this Convention include; 1) The two High Contracting Parties engage to abstain from all interference in Tibet's internal administration; 2) Great Britain and Russia engage not to enter into negotiations with Tibet except through the intermediary of the Chinese Government; 3) The British and Russia Governments respectively engage not to send Representatives to Lhasa; 4) The two High Contracting Parties engage neither to seek nor to obtain, whether for themselves or their subjects, any concessions for railways, roads, telegraphs, and mines, or other rights in Tibet. He believed that these articles meant the rights that he had striven for in the Lhasa Treaty for Britain three years ago were lost. According to the Lhasa Treaty, "No concessions for railways, roads, telegraphs, mining or other rights shall be granted to any Foreign Power, or to the subject of any Foreign Power. In the event of consent to such concessions being granted, similar or equivalent concessions shall be granted to the British Government". "any foreign power" here implicated Russia. But the Lhasa Treaty did not impose any restrictions on Britain. However, based on the Convention between Great Britain and Russia, Britain was also restrained, which Younghusband took to heart.

Younghusband complained that the British Government was carrying out a set of policies (controlling Simla by way of London, and then controlling various provinces through Simla and in the end controlling local officials by way of province governments), which made the Indian Government lose its rights and positions. Most of ministers in the Indian Office of the British Government never traveled to India, nor knew anything about India, but they interfered in the affairs there wantonly. And the Parliament just relied on the "wills of ignorant voters, who had a belief that "India is not my business". Thus, the interests of the Indian colony were neglected, even sacrificed. So Younghusband made the following suggestions: all British politicians who would act as senior officials in an Indian colony should make investigations in India; the viceroy of India should return to Britain so as to have a better understanding of the situation there during his five years' tenure of office; officials subordinate to the minister of Indian Affairs in the government should be trained in India and then sent back to India to work so as to change the situation that officials under the minister of Indian Affairs were all laymen; officials recently coming from the British government should work in the Indian Government so that the Indian Government could know the situation in Britain and the administration by the minister of Indian Affairs. Moreover, the British government should not despise officials from the Indian government, and should treat them politely instead of considering them as low-grade officials. Officials who knew the opinions of the Indian Government and Tibetan affairs should take offices in legations in London, Beijing and St. Petersburg so as to establish connections.5

This book also gives an account of Younghusband's life after he returned to Britain. At the end of 1909, he returned to Britain from India after he finished his tenure of office. He at once prepared to participate in political affairs, ran for Parliament, and even strove for a position in the Cabinet. He thought that he was qualified to participate in the election, for he had made a faithful and conscientious contribution to the British Empire and he had the duty to save it from serious crisis. His campaign speeches always began by saying: "when I negotiated for the Lhasa Treaty" and the audience gave him a loud cheer. However, he failed in the end. During this period, he devoted most of his energies to writing. In 1910, he finished his book India and Tibet.

In 1930s, India and Tibet was translated into Chinese and its title was changed into History of the British Invasion of Tibet. In his book, Younghusband first recalled the facts that the British Government expected to have direct control by means of invading Tibet and all its efforts in the second half of the 18th century. He mentioned George Bogl, Thomas Manning and Macley. He gave an account of the first British invasion of Tibet in 1888 and the second in 1904. Of course, he considered the invasion reasonable and the whole book is not only full of his criticism of the less than supportive British Government in the invasion, but also of slanders and curses to Tibetans who rose vigorously to resist the aggressor troops. In any case, Younghusband was the person concerned after all, the decision-maker. In this sense, his book is of certain historic value.

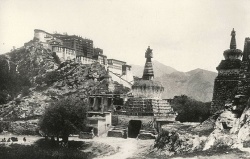

From about 1910 on, Younghusband took an interest in religion. He even planned to initiate a new "atheist religion". Later, he composed several plays on religion and became a promoter of the British Empire Religious Operas Association and the International Beliefs Association. He showed concerns about eugenics, supporting sexual liberation and believed in telepathy and mysticism. Before the outbreak of the First World War, he was invited to go to America, where he made speeches on Tibet in many spots. He found that Americans were very interested in Tibet. The speech hall was jammed with people, twice than the number of available seats there and some people had to stand outside the hall. In the William Taft Hall (the 27th president of the United States) hang pictures displaying the overall view of Lhasa and the Potala Palace. During the First World War, Younghusband participated in the war in his own unique way. He sent telegrams about the latest news to the viceroy of India everyday as propaganda materials for the British-Indian Government. He launched the campaign of "For Justice War" in attempt to inspire the patriotic spirits of the British. From the late 1920s to the early 1930s, he wrote the following books: Living Beings in the Universe beyond the Earth and The Active Universe, imaging that there existed other living beings of high intelligence in other planets besides the earth.

From the 1930s on, Younghusband, the famous stubborn imperialist in Curzon's times, changed some of his views. During the period between the two world wars, Younghusband showed sympathy for the Indians in their struggle for independence. In 1918, he believed that India could gain its autonomy at least 100 year later and he held that people in colonies should prove their ability for autonomy before they got freedom. But soon after the breakout of the Second World War, he advocated that the British should withdraw from India immediately. His racist views also changed a lot, he appraised the Indians as "wise, agile and intelligent" and said that the Asians were superior to the Europeans as a race. When Winston Churchill defamed Mohandas Gandhi, Younghusband praised Gandhis as a "true nationalist hero", who would become "one of the greatest saints" in the history of India, Later, he talked with Gandhi about the future of India in Buckingham Palace. He also accompanied Gandhi on a tour of London city. The changes in his views were probably related to the disappointment in his heart due to the decline of the British Empire.

In the period from 1934 to 1936, Younghusband, over 70, was invited to make speeches in America. In 1937, he returned after 30 years to India and advocated exchanges between different religious sects. At this advanced age, he took writing as a pleasant pastime. He often indulged his imagination about religions, and even had an extramarital love affair in his old age. His radical views that European civilization had collapsed and the only hope lay in the wisdom of Eastern religions caused his proposed radio broadcast to be cancelled (he was invited to write it). He experienced air bombardment by Nazi German planes. In July of 1972, he passed away in Dorset at the age of 79, while a small copper statue of Buddha lay beside his bed.

French gives a frank account of Younghusband's important activities throughout his life and tries to explore his inner world, hoping to display the workings of his mind. For this, he should have had a better understanding of the basic modern historic situation in Britain, British-India and China's Tibet and also an accurate knowledge of the current affairs of that period. He should also have consulted archives and Younghusband's private letters, which is not easy for a Western scholar. We should say that French has tried his best to do so. In order to write this book, he consulted many works written by Western scholars, and read private letters preserved in Britain, India and owned by Younghusband's relatives and friends. There-fore he offered readers many previously unknown firsthand materials. He spent many years following Younghusband's trails to make field investigations into many places in Asia. In 1999, he traveled to Lhasa via the Qinghai-Tibetan Road. If possible, he should have followed the route of invasion that Younghusband had taken to Lhasa. Of course, as a biography written by a Western author, French must inevitably have his own point of view so Chinese scholars probably will disagree with some of the contents of his book. There is no necessity for repetition, for readers can discover these points for themselves.

Notes:

1 Russia's Advance in Central Asia, October 8,1858, Complete Works of Marx and Engels, Vol.12,p.642

2 Younghusband: Francis Younghusband,p.136

3 Younghusband: Francis Younghusband,p.257

4 The Last Great Imperial Adventurer,p.297

5 Younghusband: Francis Younghusband, p.287, pp.306-310

From China Tibetology (Chinese Edition) No.2,2003 Translated b Xiang Hongjia