Origin And Development Of Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika And Āyurveda-From Early Times To Modern Time

Origin And Development Of Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika And Āyurveda-From Early Times To Modern Time

Darśana (philosophy)

Philosophy is generally considered to be merely speculative. But this is not true in Indian philosophy. In India philosophy is speculative but it has both the theoretical and practical aspects. Philosophy in India has been named, Darśana, which means ‘vision’, ‘insight’, ‘intuition’, etc and thus the word itself signifies its different nature. The etymological meaning of the word philosophy is ‘love of learning’. It signifies a natural and necessary urge in human being to know themeselves and the world in which they live and move and have their beings.

The Indian systems of philosophy developed and the idea that philosophical speculations were the spontaneous brain-creations of our mystic sages and Îṣis. It is a well known fact that the origin of darśana in India is almost forgotten we do not possess any chronological account as to when the great Rishis and Yogis began to dream of philosophy. In the absense of such a record we can only depend upon hypothesis helped by anumāna of śeṣavat, meaning inferring the cause from the effect. Thus we know that the earliest form of systmetized thoghts is represented by the sutras of the different philosophical systems. This itself presupposes a stage when there was no systamatization of these thoughts, which is quite evident from the study of the pre-upanisadic literature and the Upaniṣads. In these we do not see any systematic arrangements of the ideas and the views represented later on by different schools of thought. It appears that the thoughts contained in these were the common property of the intellectual community of the country. Perhaps, there was no need of systematization at that time. But later on, due to intellectual degeneration or some other inevitable causes, ideas were assimilated in certain cases by different schools and formed the backgrounds of distict lines of thinking in subsequent ages. As time went on such lines of thinking multiplied in number and began to develop each its own individual character.

This, it is impossible to write a history of the origin and development of philosophy. Because it doesnot get universal acceptance. But the history of the origin and development of Indian Philosophy can be traced in the vedas. Indian Philosophy, an autonomous system developd practically un-affected by external influences .The Upaniṣads are regarded as the fountain head of all system s of Indian Philosophy.

Classification of Darśana

long established and widely accepted tradition clasified Darśanas into Āsthika and Nāsthika. Āsthika is one who believes in the other world; and Nāsthika is one who does not believe in the other world. On the basis of this explanation even Jainism and Budhism in some of its aspect could be considered as Nāsthika system. An old popular tradition would takes the word Āsthika in the sense of ‘one who believes in God.’ If this should be accepted Jaimines Pūrva Mīmāṃsā and Kapilas Sāṅkhya, which are usually included in the Āsthika list ought to be dropped from that list, as they do not recognise Ìśvara. A post Budhistic and pre-christian tradition fixed the meaning of the Āsthika as one who believes in the infalliblity and the supreme authority, of the Veda, and the word Nāsthika is one who doesn't believe in it. This tradition has been widely accepted for a long time. According to this classification, the Sāṅkhya- yoga, the Nyāya- Vaiśeṣika, Pūrva-mīmāṃsa, Uthara-mīmāṃsa (vedānta) are deserved as Āsthika Darśanas.

The Carvāka, Jaina and Budha systems are considered as Nāsthika Darśanas. The terms orthodox and heterdox happened to be used as the English equivalent of Āsthika and Nāsthika.[1]

Origin and development of Nyāya-Śāstra

The Brāhmaṇās maintain that their religion is eternal It is based on scriptures which are said to eternal; but revealed in different periods of time of seers or sages called Îṣis. These scriptures are called Vedas, which comprise the Saṃhitās and Brāhmaṇas. The Brāhmaṇas called the doctrine of soul and its destiny profounded in the Āraṇyakas has existed in Indian from the beginning of time. They tried to place the Brāhmaṇic religion one of firm basic unshaken by the influence of time. It does not however find favour with modern scholars. Their view was all human civilization, including the Indian people grew up by a process of evolution. So the conception of soul like evrything else has under-gone stages of development in the course of ages, these stages may clearly be seen in the doctrine of the souls as given in the saṃhitās, Brāhmaṇas and Upaniṣads.

Ātmavidya (the science of soul)

The Upaniṣads which dealt with the soul and its destiny constituted a very important branch of study called Ātmavidya, (the science of soul), Adhyātmavidya (the divine science), which is the foundation of all other sciences. Ātmavidya was at a later stage called Ānviṣiki (the science of enquiry), Ānviṣiki while comprising the entire functions of Ātmavidya was infact different from it and from the Upaniṣad.

The distinciton between Ātmavidya and Ānviṣiki lay in this that, Ātmavidya is consists certain dogmatic asertions about nature of soul. Ānviṣiki contained reasons suporting those assertions. Ānviṣiki delt infact with two subjects namely soul and hetu theory of reasons. It was developed into philosophy called darśana. It dealt largley with the theory of reasons was developed in to logic. This bifurcation of Ānviṣiki into, philosophy and logic commenced about 550 B.C. when Medhātithi Gouthama expounded the logical side of Ānviṣiki. Ānviṣiki in its philosophical aspect called darśana. Darśana literally signifies seeing, it is infact the science which enable us to see our soul.

Later Ānviṣiki the theory of reason developed to logic, and it is known by various names, like hetu śāstra, hetu vidya (the science of reasoning) and it was also called Tarkavidya (the art of debate) it dealt the rules for carrying on disputations in learned assemblies. The Ānviṣiki is also called the Nyāya-śāstra ( the science of true reasoning)

It is said that the Cārvāka, Kapila, Punarvasu Ātreya, Dattātreya etc. are considered to be the early teachers of Ānviṣiki in its developd form of philosophy and logic.

Medhātithi Gautama, the founder of Ānviṣiki, (Circa 550 B.C.). The teachers mentioned above delt with some particular topics of Ānviṣiki, the credit of founding, the Ānviṣiki. in its special sense of science is to a sage named Gothama or Gouthama. A village named Gouthama sthāna mentioned as the place his birth and a fare is held every year in that village. It is situated in Midhila at a distance of 28 miles north east of modern Darbhāṅga. Thre are different vertions of the story about Medhātithi Gouthama seems to have belonged to him and his samily.

It has been previously observed that Nyāya was one of the various names by which the Ānviṣiki was designated in its logical aspect. In the first stage logic was generally designated as Ānviṣiki, Hetuśāstra, or Tarka vidya, but in the second stage as we find in the Nyāya-Bhāṣya widely known as Nyāya-śāstra. The word Nyāya popularly signifies' right or justice.' The Nyāya- śāstra is therefore the science of right or true reasoning.

Technically the word Nyāya signifies a syllogism (as speech of five parts) and the Ānviṣiki was called Nyāya-śāstra. Vātsyāyana defines, no doubt, Nyāya as an examination of objects by evidences. Viśwanādha explains Nyāya svarūpa as the essential form of syllogism which consits of its five parts.The term Nyāya and inference for the sake of others in which a syllogism is specially employed. In view of this technical meaning we may interprete Nyāya-śāstra as the scienc of syllogism or the science of inferene for the sake of others that is the sciene of demonstration. The term Nyāya in the sense of logic does'nt appear to have been before the first cnetury.A.D. The Caraka Saṃhitā is so far as we know, contains for the first time and exposition of the doctrine of syllogism under the name of Sthāpana (demonstration), it is presumed that the word Nyāya as an equivalent for logic came into use about the composition of that saṃhitā. The word became very popular about the second century A.D.when the Nyāya-sūtra was composed. Vātsyāyana uses the expression of 'Parama-Nyāya' for the conclusion which combines all the five parts of syllogism.

The history of Indian logic indicates that nothing is definitely known about the early teachers of Nyāya-śāstra. In the Ādi Parva of Mahābhārata we find that the hermitage of Kāśyapa was filled with sages who knew the true meaning of demonstration, reputation, and conclusion.The technical terms of Nyāya-Śāstra as used in the Caraka Saṃhitā, reasonably inferred that the sages who delt with them in the hermitage of Kāśyapa were the early exponents of that Śāstra.

Nyāya Sūtra - The first systematic work on Nyāya Śāstra

The first regular work on the Nyāya-Śāstra is the Nyāya sūtra or "aphorisms on true reasonings". It is divided into five books each containing two chapters called 'āhnikās'. Perhaps the Nyāya-śāstra, as it exist at present is not entirely the work of one person, but has been enlarged by interpolations from time to time. The principle subjects treated in the Nyāya-sūtra, may be grouped under the following heads. Pramāṇa (means of knoledge), Premeya (the objects of knowledge), Vāda (a discussion), Avayava (syllogism), Anyamataparīkṣa (the examination of the doctrine of other systems).

Akṣapāda the author of Nyāya-sūtra (150 A.D.)

In the early commentaries of Nyāya sūtra the auther of the sūtra is distinctly named as Akṣapāda. Vātsyāyana in the Nyāya Bhāṣya says that the Nyāya Philosophy manifested itself before Akṣapāda the foremost eloquent, while, Udyodakara in his Nyāya-vārttika affirms that it was Akṣapāda the most excellent of sages that spokes ot the Nyāya-śāstra in a systematic way.

Nyāya-kośa mentions two legends two account for the name Akṣapāda as applied according it to Goutama. it Is said that Gouthama was so deeply absorbed in philosphical contemplation that one day during his walks he fell un-wittingly into a well, out of which he was rescued with great difficulty. God therefore mereficullly provided him with a second pair of eyes in his feet, to protect the sage from further mishaps. This is a ridiculous story manufactued merely to explain the word aksapada as composed "Akṣa" (eye) and "pāda " (feet).

The Nyāya-sūtra treats of its categories through the process of enunciation (Uddeśa), definition (lakṣaṇa) and examination (parīkṣa). Enunciation is mere mentions of the categories by name. Definition consists in setting for that character of a category, which differentiates it from other categories. Examination is the settlement of by reasoning of the question whether the different of certain category is really applicable to it. Book first of the Nyāya-sūtra deals with enunciation and definition of sixteen categories and remaining four books are concern with a critical examination of the categories.

The arrangement categories in the Nyāya-Sūtra

The Nyāya-sūtra treats of sixteen categories which are called padārthās namely, pramāṇa which signifies the means of knowledge. Second is premeya, which refer to the objects of knowledge. The third category saṃśaya, having rouse a conflicting judgement about the case, the disputat in pursuance of his prayojana (purpose) cites a parallel case called, a familiar instance dṛṣṭānta, which is not open to such a doubt. The case is then shown to rest on Sidhānta, tenets which are accpted by both the parties. That the case is valid is further shown by an analysis of it into five parts called Avayava or members of Syllogism. Having carried on Tarka, confutation against all contrary suppositions the disputent affirms his case with Nirṇaya, cetainity. If his respondent, not being satisfies, with this process by demonstration, advanced and antithesis, he will have to enter upon vāda, or discussion which will jalpa, a wrangling and vitaṇḍa, failing to establish his antithesis he will employe hetvābhāsa or fallacies of reasons. Chala quibble and Jāti analogies the exposure of which will bring about his Nigraha stāna of defeat.[2]

1. Pramāṇa (means of knowledge)

Pramāṇa is the means leading to a knowledge-episode (pramā) as its end. Perception, inference, comparison, and word (verbal testimony) these are the means of right knowledge. Perception is that knowledge which arises from the contact of a sense with its object, and which is determinate, unnamable and non erratic. Inference is knowledge which is preceded by perception, and is of three kinds, viz., a priori, a posteriori and commonly seen. Comparison is the knowledge of thing through its similarity to another thing previously, well known word (verbal testimony) is the instructive assertion of a reliable person.

It is of two kinds, viz., that which refers to matter which is seen, and that which refers to matter which is not seen.

2. Premeya (The objects of right knowledge)

Soul, body, senses, objects of sense, intellect, mind, activity, fault, transmigration from pain and release – are the objects of the right knowledge. Desire, aversion, volition, pleasure, pain, and intelligence are the marks of the soul. Body is the site of gesture, senses and sentiments. Nose tongue, eye, skin, and ear are the senses are produced from elements. Earth, water, light, air, and ether – these are the elements. Smell, taste, color, touch, and sound are objects of the senses and qualities of the earth etc, intellect, apprehension and knowledge these are not different from one another. The mark of the mind is that there don’t arise (in the soul) more acts of knowledge than one at a time. Activity is that which makes the voice, and body began their action. Faults have the characteristic of causing activity.

Transmigration means re-birth. Fruit is the thing produced by activity and faults. Pain has the characteristic of causing uneasiness. Release is the absolute deliverance from pain.

3. Doubt (Saṃśaya)

Doubts, which is a conflicting judgment about the precise character of an object, arises from the recognition of properties common to many objects, or of properties not common to any of the objects, from the conflicting testimony, and from irregularity of perception and non perception. Doubt is of five kinds, according as it arise from, recognition of common properties, recognition of properties not common conflicting testimony, irregularity of perception and irregularity of non- perception.

4. Purpose (prayojana)

Purpose in that with an eye to which one proceed to act. An actual doubt, however, cannot by itself necessitate the required inquiry. The inquiry or the philosopher must have, it is believed, some prayojana, purpose, some intended goal in mind. Philosophic inquiry according to this view, does not originate in our idle curiosity, nor is it to be regarded as a purposeless exercise. Some people believe that philosophic inquiry is aimed at the four prescribed goals dharma, artha, kāma, mokṣa.

5. Example (Dṛṣṭānta)

A familiar instance is the thing about which, an ordinary man and an expert entertain the same opinion. Besides doubt and purpose an inquiry must have something to go upon. There must be observed data and other principles which could be used as premises of the argument to follow the Nyāya covers these matters under two technical terms, Dṛṣṭānta and Siddānta.

Dṛṣṭānta is an object of perception in respect of which the observation of common people and of experts is undoubted. It is a Prameya. It has been separately mentioned on account of its importance. Both inference and revelation rest upon it without it neither inference nor revelation would be possible. The application of Nyāya depends upon it.

6. Tenets (siddānta)

A tenet is a dogma resting on the authority of a certain school, hypothesis, or implication. When an object is at last known in the form “such and such exists”, it is called a siddanta an established tenet, a conclusion. The tenet is of four kinds wing to the distinction between a dogma of the schools, a dogma peculiar to some school, a hypothetical dogma and implies dogma. A dogma of all the schools is a tenet which is not opposes by any school. A dogmas peculiar to some school is a tenet which is accepted by similar schools, but rejected by opposite schools and ia claimed by at least one school. A hypothetical dogma is a tenet which, if accepted leads to the acceptance of another tenet. An implied dogma is a tenet which is not explicitly declared as such, but which follows from the examination of particulars concerning it.

7. Members of syllogism (Avayava)

The members are proposition, reason, example, application, and conclusion. Avayava (members) that is the five beginning with pratijμa, are so called with reference to the concatenation of words considered as a whole, while complete the establishment of the object to be established. A philosophical argument as envisioned here is an inference based upon evidence. The full articulation of this inference consists of five steps, each step being a demonstration of different parts of the process by which a conclusion is reached. The steps are –

- 1. Proposition – the hill is fiery,

- 2. Reason – because it is smoky,

- 3. Example – whatever is smoky is fiery as a kitchen,

- 4. Application – so is this hill (smoky),

- 5. Conclusion – therefore this hill is fiery.

In the schema given above, the first step is called pratijna, where one states what one is going to prove. The second step assigns a reason or ground or evidence adduced and what is so be proved in the case under consideration. The most important step here is however the fourth step, which combines the second and the third to formulate what may be called the full fledged premise of the argument before the conclusion is drawn in the fifth step.

8. Confutation (Tarka)

Confutation, which is carried on for ascertaining the real character of a thing of which the character is not known, is reasoning which reveals the character by showing the absurdity of all contrary characters. Which takes the form of a supportive argument but unlike the previous one, it is not directly based upon empirical evidence. The real nature of Tarka (literally ‘reasoning’ argument) has been the subject matter of controversy among Indian philosophers throughout history.

9. Ascertainment (Nirṇaya)

Ascertainment in the determination of a question through the removal of doubt by hearing two opposite side. Nirṇaya is tattvaguna, knowledge is truth. It is the result of the pramāṇas, vāda (discussion) ends with it. For its maintenance are jalpa and vitaṇḍa. Tarka (hypothesis) and Nirṇaya (ascertainment) help carry on the world. For this reason Nirṇaya though included in the Prameya, has been separately mentioned.

10. Discussion (vāda)

Discussion is the adoption of one of two opposing sides- what is adopted is analyzed in the form of five members, and defended by the aid of any of the means of right knowledge, while its opposite is assailed by confutation, without deviation from the established tenets. Vāda is discussion in which different speakers take part, each seeking to make good his own hypothesis, and which ends with establishments emphasize its special feature. By the use of it as so defined – tattva vijμāna, knowledge of truth, is attained.

11. Wrangle (jalpa)

Wrangling, which aims at gaining victory, is the defense or attack of a proposition in the manner aforesaid, by quibbles, futilities and other processes which deserve rebuke. Jalpa, vitaṇḍa are verities of vāda and are employed to keep up the effort in the pursuit of truth. A wrangle is activated by a desire for victory, and not by a desire for the determination of truth.

12. Cavil (vitaṇḍa)

Cavil is a kind of wrangling which consists in mere attacks on the opposite side. It is said to be characterized by the lack of any attempt to prove the counter thesis. In other words the debater here is engaged simply in the refuted of a position but does not give the opponent chance to attack his own position.

13. Fallacy (hetvābhāsa)

Fallacies of a reason are the erratic, the contradictory, the equal to the question, the unproved, and the mistimed. The fallacies are faulty reason. All fallacies of the reason, which cannot prove the existence of predicate in the subject. The erratic is the reason which leads to more conclusions than one. The contradictory in the reason which oppose what is be established. Equal to the question is the reason which provokes the very question, for the solution of which it was employed. The unproved is the reason which stands in need of proof, the same way as the proposition does. The mistimed is the reason which adduced when the time is passed in which it might hold well.

14. Quibble (chala)

Quibble is the opposition by the assumption of an alternative meaning. A quibble (chala) consists in attacking a proposition by assuming another meaning of a word, which is not intended by the speaker. It is of three kinds, viz., quibble in respect of a term. Quibble in respect of genus, and quibble in respect of a metaphor. Quibble in respect of a term consist in willfully taking the term in a sense other than that intended by a speaker who has happened to use it ambiguously. Quibble in respect of a genus consists in asserting the impossibility of thing which is really possible, on the ground that it belongs to a certain genus which is very. Quibble in respect of a metaphor consists in denying the proper meaning of a word by taking it literally while it was used metaphorically and vice versa.

15. Futility (Jāti)

Futility consists in offering objections founded on mere similarity or dissimilarity. Futility is a sophistical refutation of an argument on the ground of mere similarity or dissimilarity without the support invariable concomitance of the reason with the predicate. There are twenty four kinds of futilities; we shall use D for disputant, O for an opponent, S for the subject or minor term. P for the predicate or major term, M for the reason or middle term, E for the example, and E for the counter example. The analogues are as follows:

- Sādharmya-Sama,

- Vaidharmya-Sama

- Utkarṣa-Sama,

- Apakarṣa-Sama,

- Varṇya-Sama,

- Avarṇya-Sama,

- Sādya-Sama,

- Prāpti-Sama,

- Aprāpti-Sama,

- Prasaṅga-Sama,

- Pratidṛṣṭānta-Sama,

- Anutpatti-Sama,

- Samśaya-sama,

- Prakaraṇa-Sama,

- Ahetu-Sama,

- Arthāpatti-Sama,

- Aviśeṣa-Sama,

- Upāpatti-Sama,

- Upalabdhi-Sama,

- Anupalabdhi-Sama,

- Anitya-Sama,

- Nitya-Sama,

- Kārya-Sama.

16. A point of defeat (nigrahastāna)

An occasion for rebuke arises when one misunderstand, or does not understand at all nigrahastana, are grounds of defeat in a philosophical debate. They are occasions for rebuke due to will misunderstanding or want of understanding. They consists in one’s inability to refute an opponents thesis or to establish one own thesis refuted by him. There are twenty two kinds of nigrahastāna.

- 1. pratijμā-hāni,

- 2. pratijμāntara,

- 3. Pratijμa-virodha,

- 4. pratijμa-sannyāsa,

- 5. hetvāntara,

- 6. Arthāntara,

- 7. nirartaka,

- 8. avijμatartha,

- 9. aparthaka,

- 10. aprapta-kala

- 11. nyūna,

- 12. adhika,

- 13. punarukta,

- 14. Ananubāsa,

- 15. aμjana,

- 16. apratiba,

- 17. vikṣepa,

- 18. matanujμa,

- 19. paryanuyojyapekṣaṇa,

- 20. Niranuyojyānuyoga,

- 21. apasidhānta,

- 22. hetvābhāsa.

Origin and Development of Vaiśeṣika Darśana

The system of the Vaiśeṣika is even more radical than the Nyāya. As a system of philosophy, the Vaiśeṣika is more symmetrical and also more uncompromising. The Vaiśeṣika system was an early realistic school whose main achievement lay it its attempt to classifying nature into like and un-like groups it also posited that all matter was made up of tiny and indestructible particles, i.e., atoms that aggregated in different ways to form new compounds that formed the variety of matter that existed on the earth.

The term ‘Vaiśeṣika’ is derived from the root ‘viśiṣ’ meaning ‘distinct’. The term viśeṣa means ‘the difference between’, characteristic difference special property. The great Maharṣi Kaṇāda is considered to be the founder of Vaiśeṣika system of philosophy and also considered to be the author of the Vaiśeṣika-sūtra (300.B.C.). His philosophy was described through the enumeration of the following concepts. Dravya (substance), Guṇa (Quality), Karma (Action), Samānya (Generality), Viśeṣa (Particularity), Samavāya (Inherence), and Abhāva (Non-existence).[3]

Dravya (substance), was understood as the specific result of a particular aggregate effect, i.e., the combination of atoms in unique way. Substances were repositories for qualities and actions. Guṇa or quality which resided in a Dravya. Qualities did not however contain qualities themselves. Twenty four qualities enumerated such as –color (rūpa), taste (rasa), smell (gandha), touch (sparśa), number (Saṅkhya) , dimension (parimāṇa), separateness (pṛthaktva), conjunction (samyoga), disjunctions (vibhāga), posteriority (paratva), priority (aparatva), heaviness (gurutva), fluidity (dravatva), viscidity (sneha), sound (śabdḥ), knowledge (buddhi), pleasure (sukha), pain (dukha), desire (iccha), aversion (dveṣa), effort (prayatna), merit (dharma), demerit (adharma), and tendency (samskāra).

Karma or (Action) represented physical movement, unlike quality which was passive, karma was dynamic. Action was the determinant of conjunction, disjunction. Five types of action were noted:- throwing upwards or down wards, contraction, expansion and locomotion.

Sāmānya or (generality- was seen as a mental construct to create common classes of substances, qualities or actions while Viśeṣata (particularity) was used to identify and separate individual items from their general classes. Samavāya or (inherence) –was a relation that existed in those things that could not be separated destroying them.

Four categories of Abhāva or (negation) or non-existence were listed: Prāgabhāva or non-existence, referring to the absence of an object before its creation; Pradhvamsābhāva or posterior negation, as the absence of an object after it had been destroyed; or Anyonyābhāva or mutual non-existence, referring to an object being distinct and different from the other, indicating non-existence in the past, present and future, citing the example of air as permanently lacking in smell.[4]

Among the numerous system of philosophy that evolved in India during the last three thousand years, Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika occupy a unique position, both on account of their cardinal doctrines and on the mass of learning that has accumulated around them. Nyāya is a system of atomistic pluralism and logical realism. It is closely allied to the vaisesika system which is regarded as ‘samānatantra’ or similar philosophy. Both systems agree in viewing the earthly life as full of sufferings and the destruction of those sufferings is the supreme and of life. Both also agree that bondage is due to misapprehension of things and that liberation is due to right knowledge of categories.

Thus there is some common style between these orthodox systems. At the same time there are some important difference between them, which may be noted. First, while Vaiśeṣika recognize six categories and classifies all reals under them, the Nyāya accept sixteen categories. In Nyāya philosophy the first category is Pramāṇa or the means of valid knowledge. This clearly brings out the predominality of logical and epistemological character of Nyāya. Nyāya accepted four means of valid knowledge. But Vaiśeṣika accepted only two means of knowledge.

Roughly speaking, the literature of the Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika systems extends over a period of twenty-two centuries, that it, from about the 4th century B.C. till very recent times, of which the last two hundred years, not being distinguished by any original works, may be left out of account. The history may be divided into three periods: the first from about 400. B.C. to 500. A.D., the second from hence to 1300. A.D. and the third after that till the end of the last century. The only known representatives of the first period are the two collections of aphorisms going under the name of Gotama and Kaṇāda respectively, and perhaps the scholium of Praśastapāda also; but there must have existed other works now lost.

The second period is pre-eminently distinguished by a series of commentaries on these sūtras beginning with Vātsyāyana and comprising several works of acknowledged authority. The third period saw the introduction of independent treatises and commentaries on them which at last dwindle down into short manuals like, Tarka-Saṃgraha and Tarka-Kaumudi. These three periods in the development of the two systems. The first may be called the age of the formation of doctrine in the sutras; the second that of their elaboration by commentators; and the third that of their systematization by writers of special treatises. The first characterized by great originality and freshness, the second by a fullness of details and the third by scholastic subtlety ultimately leading to decadence.

This division may sometimes overlap, for we have treatise like Tarkīka-rakṣa and Saptapadārthi before 14th century, so we have commentaries on the sutras like Śaṅkara Misra’s Upaskāra, and Viśvanatha’s Vṛtti, written afterwards. This does not, however, affect our general conclusion that the writings of the 14th century and onwards are in marked contrast with those of the preceding age. The exact duration of these periods may have varied a little in the case of the two systems, but the order is the same. The mutual relation of these two systems, however, appears to have changed at different times. During the first period they seem to have been two different systems, independent in origin but treating of the same topics and often borrowing from each other. Vātsyāyana regards them as supplementary. In the second period, however, they become somewhat antagonistic, partly owing to an accumulation of points of difference between the two, and partly on account of the alliance of the Vaiśeṣika with the Buddhists. The third period saw the amalgamation of the two system, and we come across many works, like the Tarka-Saṃgraha for instance, in which the authors have attempted to select the best portions of each and construct from these fragments a harmonious system of their own.

According to S.C.Vidyabhūṣaṇa the school of Indian logic is divided into three period, the ancient school of Indian logic, 2. Medivial period and 3. Modern school of Indian logic. In the first period of the school of logic work text Nyāya-sūtra of Gautama and their commentaries, the medieval school of logical work is Pramāṇa-samuccaya by Diṅnāga, and their commentaries. The modern school of Indian logical work is Tatvacintāmaṇi of Gaṅgeśa and their commentaries.

The age of commentaries proper begin with Vātsyāyana, other wise known as Pakṣila Swāmin, whose commentary on Gouthamas work is the oldest known work. Vātsyāyana must have lived about the end of the 5th century; A.D. Udyotakara was next to Vātsyāyana with his Nyāya-Vārttika in the 6th century A.D.

After Udyotakara there seems to have occurred another long gap in the succession of orthodox Nyāya writer until the end of the 10th century, when a revival took place under the influence of the author of Nyāya-kandali which is the earliest known commentary on Praśastapāda Bhāṣya. This interregnum soto say is the more inexplicable as the period was one of intellectual activity. Controversies between the Brāhmiṇs, as represented by the Mīmāṃsakas and Vedāntins on the one hand and the Budhists and Jainas on the other occupy almost the whole of this period.

The interregnum from Udyotakara’s time to the end of the 10th century may have been produced by various causes which cannot be known at present; nor can we say for certain how the subsequent revival was brought about. Nyāya and Vaiśeṣika proper can be assigned to the interval between the 7th and the 10th century. After this a series commentaries come under the base of that notable commentaries of Praśastapāda and Vātsyāyana who had then come to be looked upon as ancient authorities to explained and enlarged with reverence, rather than criticized or corrected by abler successors.

The first writer of this age of revival was Sridara who wrote his Nyāya-kandali in 991 .A.D. Śrīdhara takes great pains to refute the opinions of Kumārila and Sureśwara, and Mandana etc. Rajasekara a Jaina commentator on Nyāya kandali mentions three other commentaries on Praśastapāda Bhāṣya, besides Śrīdharas’s work, viz the Vyomāvati of Śivāditya, the Kiraṇāvali of Udayana and the Līlāvati of Śrīvalsa or Vallabha all of which were written after Śrīdharas’s work but before the end of the 13th century. The chronological order of these writers may be fixed as Śrīdhara, Vallabha, Udayan, and Śivāditya. Each of them was distinguished for some new conception or original treatment of old topics. Udayana, who was followed by Vācaspati Miśra in the 11th century, Vācaspati wrote commentaries on all the principles of philosophical systems, and whose work have been deservedly held in the highest estimation by the succeeding generation. Vācaspati Miśra wrote an able commentary on the Vārtikas of Udyotakara’s, called Vārttika Tātparyatīka and this Tīka of Vācaspati became the text of another commentary. So many other commentaries and writers come under this period.

The end of the 14th century saw the commencement of the third period of Nyāya system. Gaṅgesa, or Gaṅgeśopādyāya the author of Tatvacintāmaṇi, may be said to be its oracle. He founded a new school of text-writers and commentators in this period, the exact date of Gaṅgeśa is not known, but who probably lived about the end of the 11th century. Gaṅgeśa was followed by two writers of note, Jayadeva and Vāsudeva. Jayadeva otherwise known as Pakṣadaramiśra, wrote his Mānyaloka a commentary on Gangesa’s Tatvacintāmaṇi about five centuries ago, that is the middle of the 14th century. Vāsudeva Miśra, a fellow student of Jayadeva and the author of a commentary of Gaṅgeśa’s work.

Vāsudeva Sarvabhouma has been another remarkable man. Vāsudeva’s pupil Rekhunadasiromani, who wrote Dītiti the best commentary on Gangesa’s Tatvacintāmaṇi and is acknowledged to be the highest authority among the modern Naiyāyikas. Rakhunada’s immediate successors were Madhuranatha, Harirama Tarkālamkara, and Jagadīśa, who were followed by their respective pupils, Reghudeva and Gadadara. Gadadara may be called the prince of Indian school men, and in him the modern Nyaya dialectics reached its climax. Gadadara must have belonged to the end of 16th century or the beginning of the 17th century.

The generation next after Gadadara is represented by two writers standing on a somewhat lower level but equally famous. These were Śaṅkara Miśra, the author of Upaskāra, a commentary on Kaṇādas Vaiśeṣika sūtra and Viśvanātha who wrote Siddānta Muktāvali and Gautama sūtra Vṛtti. Another sign of the Nyāya system was the production of manuals adapted to the understanding of the beginners and explaining the latest ideas in the simplest language. The Bhāṣā-paricheda, the Tarka Samgraha and Tarkāmṛta, etc, are instance of this class of book. The two exceptions are Viśvanathas Siddānta Muktāvali and Annambhaṭṭas Tarka-Samgraha, which being written by the authors of the original work are more like larger editions of those texts than were explanatory glosses. These manuals proved very handy and useful to students.

Let us consider the origin and development of Āyurveda.

An introduction to Āyurveda

Āyurveda is one of the most ancient sciences of life invented during Vedic peirod, which may be 1000 to 2,500 B.C. Though invented in India it is a most precious gift of the wisdom of ancient risis for the welfare of mankind, irrespetive of race, religion and nationality. The aim and objectives for development of this system is described as:

'Preservation of the healthy people and curing persons suffering from disease'.

This system deals elaborately with measures for healthy living during the entire span of life and its various phases, besides dealing with principles for maintenance of heath. It has also developd a wide range of therapeutic measures to combat illness.

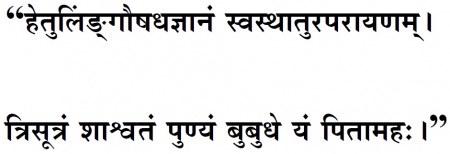

Bases and branches of Āyurveda

The subject of Āyurveda is for health as well as for diseased persons and for both these groups it is three fold, viz:

- 1. Hetuśāstra - Causes of etiology

- 2, Liṅga śāstra - signs snd symptoms

- 3. Auṣadha śāstra - diet and drugs

Basic Principles of Āyurveda

Paμcabhūta siddhānta, Tridoṣa theory, action of drugs based on rasa, guṇa, vīrya, vipāka, and prabhāva, sāmānya, and viśeṣa siddhānta, etc. are some of the basic principles which are applied for prevention and cure of diseases.

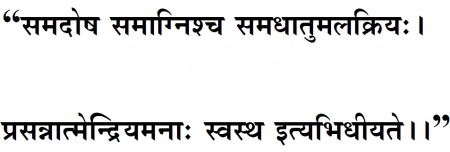

Definition of health in Āyurveda

The positive health according to Āyurveda is not only balance of dosas, proper digestion and physiological functions but also spiritual, mental and sensory pleasure of every Individual .i.e. Āyurveda the traditional system of Indian medicine is a special branch of knowledge on life dealing the whole branches of life, the body and mind. Our tradition teach us the four primary objectives of human life are, Dharma, Artha, Kāma and Mokṣa, performance of such rites as are conducive to the well being of the individual as well as the society. Achievements of these four fold objectives only through a good healthy body. So the man has therefore, eternally endeavoured to keep himself healthy and free from miseries. The scope of Āyurveda is not limited to physical health alone. It also seeks to promote a totality of physical, mental, and spiritual health in the context of man's interaction with his environment.

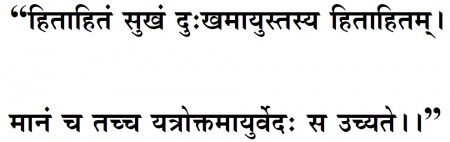

The term 'Āyurveda' is divided into two, 'Āyus', and 'Veda'. The former means jīvita or life and the latter,' knowledge' or more preciously 'science'. The scope of the term ayus extends to the understanding of life in all its conditions and bearings. Caraka defines:-

Āyu' comprises sukha (happiness), dukha (sorrow) hita (good), and ahita (bad). Sukhamāyuḥ or a life of happiness is free from physical and mental disease, endowed with vigour, strength, energy, and vitality, and full of all sorts of enjoyment and success. Asukhamāyuḥ or a life of dukha is just the opposite. Hitamāyuḥ a good life, indicates a life of honest disposition, self control, and self-restraint, which is prove to do what is beneficial to this world and the next. The opposite of this is ahita. Āyus is also defined by Caraka as life with body, sense organ, three basic principles, and the soul, it is also a cycle of nityaga and anubandha, ie, of perpetual change and progress. Āyurveda deals with these four conditions of life. It is also concerned with the polongation of life.

Origin and Antiquity

The available records of the history of Āyurveda indicate that the origin and antiquity of Āyurveda have been examined from two considerations: (1) myth and tradition, and (2) historical analysis. Tradition has it that Āyurveda is of divine origin from Brahma who later on communicated this knowledge to the Aśvins and from the twin divinities it come to Indra. Its human tradition began with the transmission of this divine knowledge to two mythical personages, Bharadvaja and Dhanvantari, who in their turn were responsible, for the two streams of Āyurveda, ie, medicine and surgery. Traditionally Bharadvaja specalized in both medicine and archery or śalya that is surgery. It therefore appears that the two streams originated not from two persons but from one under two appellations. This is corroborated by the association of Dhanvantari with his incarnated name Divodasa and subsequently with Bharadvaja in the Îg-Veda and the later Vedic texts.[8]

The divine origin of Āyurveda has been mentioned by Caraka and Suśruta as well as by later authorities. Possibly some common sources were relied upon by these two medical authorities in this regard. Caraka (1.30.27) hold this divine knowledge of Āyurveda as eternal, but considers it have a beginning from its first systematized comprehension or instruction.

While tradition would have us believe in the eternity of Āyurveda, historical consideraitons lead us to trace its origin to pre-Āryan times, infact, different streams of thought and ideas are found to have been incorporated through ages in the various branches of Āyurveda. Its medical corpus is an extension and systematization of earlier medical knowledge of the pre-Āryan and Indo-Āryan peoples.Its philosophical speculation and logical deliberations in the understanding of the creation of the world in the context of material components of the body and in finding out the aetiology of diseases are borrowed from different philosophical systems, particularly Sāṅkhya and the Nyāya- Vaiśeṣika. These contributed to the development of Āyurveda as we have it today.

Historical Analysis

The history of development of the Āyurveda may conventionally divide into six different periods.

Different periods of Āyurveda

Pre-Vedic Period

Archeological remainings concern Pre-Āryan medical elements unearthed form different sites of Indus and pre-Indus cultures testify to rudimentory ideas about some medical and surgical practices. Surgical activities are inferred from triphined human skulls and curved knives from two pre-Indus sites in Kashmir and Kalibanga. Pre-Āryan civilization, going back to the third millenium B.C, from the Archeological excavations at Mohenja-daro, Harappa and many other regions out side, it indicates that the medical practices of some health and hygeinic measures in pre-Aryan times. Manufactured impliments and bricks made in kilns and engravings in precious stones, indicates a high level knowledge of the physical and chemical sciences, likely to be matched by a similar knowledge of medical drugs and compoundings.This is no doubt a mere conjecture, but th existence of a high level of social sanitation and of public hygeine in these communities is fully borne out by archeological findings.[9]

While the Pre-Āryan elements led to the knowledge of the development of some medical practices in Āyurveda, indo-Āryan medical elements facilitated the growth of some concepts and theories.Thses are mainly noticed in cosmo-physical speculatious about the three basic constituents of living organisms, viz., vāyu, pitta, and kapha (b) ideas about the aetiology of disease, and (c) belief in the association of medical treatment with god physicians. Cosmo-physiological speculations relate to the humoral theory of Āyurveda which propounds that wind (vāyu) bile (pitta), and phlegm (kapha) are the three basic elements activating, sustaining, nourishing and maintaing the life- principle.[10]

Indian Medicine in Vedic period

The Indian system of medicine is almost as old as Indian civilization and a rich heritage of Inida. The tradition of Indian medicine, characterised as Āyurveda is said to have its origin from Vedas, like other traditional sciences and arts ancient India, ie, science philosophy, culture religion energy discipline in Indian has got nourishment from the vedas. It is regarded as the repository of knowledge and super knowledge. It is believed that Vedas created by Brahma, for the universal consciousness, and the same were re-arranged by 'Vyāsa' under the four heads, Îgveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda and Atharvaveda. There are four upavedas viz. Dhanurveda, Sthapatya Veda, Gandharvaveda, and Āyurveda respectively. The Vedic Indian's attitude towards the diseases was dominated by the belief of evil spirits, demon, and othe malevolent forces invaded the body and caused their victims to exhibit a state of disease, and this is treated by rituals (mantras). An elaborating healing ritual was performed to restore a patient, attacked by a disease domen or suffering an injury.[11]

Āyurveda and Atharva Veda

Îgveda is considered as old among the four Vedas. In its conseptual aspects Āyurveda has greater affinity to Îg-vedic notions, while in practice it draws much from Athrava-vedic medicins.Its relation to the Atharva -Veda is seen its (1) twofold objective of the curing of disease and the attainment of a long life;[12] and (ii) anatomical and physiological ideas. Under the second category may be cited (a) three types of bodily channels-sira, dhamani, and nādi-used in th sense of duct in th Atharva -Veda and corresponding to sira, dhamani, nadi of Āyurveda which mentions an additional channel (strotas),[13] (b) idea of five vital breaths common in the two systems;[14] (c) osteological ideas in connection with the number and nomenclature of bones; and (d) ojas (ailbumen), the vital element in the body recognized in Athrarvan medicine and in Āyurveda.

Atharva Veda is considered as the important source of the study of the ancient Indian medicine, which is the genesis of Āyurveda, because it contains more reference to Āyurvedic concept it is considered as Upaveda of Āyurveda.

The Atharva-veda differs widely from the other Vedas, in that it is not essentially religion in character and not connected with the ritual of the Soma sacrifice. It consists chiefly of a variety of spells and incantation, intended to cure, as well as to bless and also charms of a positive character to obtain benefits, to ensure love, happy family life, health and longevity. Protection of journy, even luck in gambling.

We are well aware that Atharvaveda comprises of 20 kāṇḍa, 721 sūktas and 5977 mantra, it could be categorised into two, one that is meant for curing the diseas and create peace and prosperity (white magic) and the othe meant for wreaking haveoc (black-magic). i.e. hundreds of mantras, which indicate the inbicacies of Āyurveda, it deals in details with the three physical problems, the position of five elemets in the body, digestive system, various name of the bodily parts, names of the diseases and the physician, detail of the worm in body, and their eradiciton, various types of treatement, the science of the poisonous element, para physical science, surgery, vajikarana, the characteristics of different elements, and the herbal science.

Saṃhita period (period of Compilations)

This period witnessed the compilation of the works of ancient teachers who were the founder writers of different aspects of Āyurveda. These aspect of eight parts of Āyurveda include, kāyacikitsa (Therapecutics), Śalya-tantra (major surgery), Bhūtavidya (demonology), Kaumārabṛtya (peadiatrics), Āgada-tantra (toxicology), Rasāyana-tantra (geriatrics), and Vājīkaraṇa-tantra (Virilifications).

Kāya Cikitsa- relates to treatment of diseases affecting the whole body. Which are supposed to originate mainly from disturbances of the three humor. The first and foremost compilation was the Agniveśa-tantra of Agniveśa, based on the teachings of Ātreya Punarvasu. This work delt primarily with therapeutics but toched upon other aspects of Āyurveda excepting śalya.

Śalya-tantra (śalya literally means arrow) deals with the methods of removing foreign bodies, obstetrics, the treatment of injuries and deseases requiring surgery. and the use of fsurgical instruments, alkalsis, bandages, etc. the Suśruta-Saṃhitā is one of the great classics in Indian surgery, belonging to Divodasa-Dhanvantari School.

Śālākhya-tantra is concerned with the treatment of diseases of the body above the clacivle and use of thin bars, small sticks or probes. etc as instruments.

Bhūta-vidya treats of mental derangements and other disturbances said to be caused by demons and prescribes prayers, oblations, exorcism, drugs and soforth as remedies.

Kaumārabṛtya - Gives methods of treatment of child diseases caused by demons.

Āgada-tantra discusses methods of diagnosis and treatment of the bites of poisnous snakes,insects etc. and of herbal or othe poison cases.

Rasāyana-tantra deals with the methods of preservation and increase of vigour, restoration of youth, improvemnt of memory, and prevention of disease.

Vājīkaraṇa-tantra Concern the means of increasing virile powers.

Period of Epitoms

The Saṅgrahas, appearing from about the seventh century onwards, were epitomes of earlier texts. These summarises were of two types: Comple and partial. The eight compel texts extent today come the Aṣṭāṅga-Saṅgraha of Vāgbhata I, Aṣṭāṅga-hṛdaya of Vāghbhata II, Gdanigraha of Sadhabala, Sidhayoga of Vrinda. Śārṅgadhara-saṃhita of Śārṅgadhara cikitsāsāra saṃgraha of Vangasena, and Yogarathnakar and Bhāvaprakāśa of Bhāvamiśra. partial summaries includee numerious works relating to actiology, treatment of particular diseases, materia medica, science of pulse, diatics, etc, some of the extent work of prominance are the Rugviniścaya or Madhava (allidara of Madhavakara, Arkaprakāśa of Rāvaṇa, Cikitsāsāra saṃgraha of Cakrāpāṇidata, Navanītaka (bower manu scripts), etc.

Apart form the three aforementioned classes of Āyurvedic treaties, there exist two othe separate types of work, viz., Rasagranthas or iatro-chemical texts and nighantus or medical lexicons.

The decline of Āyurveda began in the period of the Saṃgrahas whom medical authorities started sumarising the classics and codyfing them as a separate treatise. This process accelarated in the post Saṃgraha period with the total absence of new redactions, commentaries, etc. Besides these another political and other factors are caused to decline of Āyurveda.

The birth of a rational Āyurveda may be traced to the appearance of recensions of earlier medical texts Caraka and Suśruta. Three traditions of Āyurveda exist today- are Caraka, Suśruta and the third one known as Kāśyapas. However, Āyurvedic remedies prior ot these traditions also exist, as mentioned in the earlier vedic literature, Both the Suśruta and Caraka saṃhitas are the product of several scholars, having been revised and supplemented over a period of several hundred years.

The scholar Vagbhaṭa, (7th century A.D) wrote a synthesis of earlier Āyurvedic materials in a collection of verses called the Aṣṭāṅga Hṛdayam. Another work associate with the same author, the Aṣṭāṅga Saṃgraha, contains much of the same materal is a more diffuse form, written in a mixture of prose and verse.

The works of Caraka, Suśruta, and Vāgbhaṭa are considered canonical and reverentially called the Vṛddha trayi, “the triad of ancients”, or Bṛhat trayi, “ the greator Triad”.

The date of the redaction of the Caraka-saṃhitā may be assigned to the first century A.D. on the identification of Caraka with one having the same name who happened to be the court physician of Kaniṣka. Suśrutas original text is believed to have been redacted by one Nāgarjuna between the third and fourth centureis.A.D. These two Saṃhitās bear testimony to the scientific research patient investigation, and experimentation which proceeded them and served as works of references to students and research workers alike. This is also attested by Caraka. Each of these two Saṃhitas deals with, among other subjects, anatomy, physiology, toxicology, psychic therapy, personal hygiens and medical ethics. Some differences are noticed in their presentation and treatment. Caraka an enormous compendium suffereing from repetitions, contains, a vast amount of floating tradition, of considerable historical value where as Suśruta, while sufficiently emphasizing earlier traditions and knowledge, is a much more compact and systematic work. In the treament of subjects the two compendia follow two traditions. Caraka that of Ātreya, and Suśruta that of Dhanvantari.

Caraka Saṃhitā

Planning of the text, Caraka Saṃhita

The Caraka Saṃhita is divided into eight sthānas (books) arranged in the following section and chapters

| Number of chapters | |

| 1. Sūtra sthāna | 30 |

| 2. Nidhāna sthāna | 8 |

| 3. Vimāna sthāna | 8 |

| 4. Śarārasthāna | 8 |

| 5. Indriyasthāna | 12 |

| 6. Cikitsāsthāna | 30 |

| 7. Kalpasthāna | 12 |

| 8. Sidhisthāna | 12 |

| Total | 120 chapters |

Thus the text is completed in eight sections and 120 chapters in the above order. In the first section, the chapters have been grouped topicwise having four chapters in each group. They are called as catuṣkās (quadrupluts) which deals with the drugs, health, precepts, preparations, disease, planning and diet.

The last two chapters are known as saṃgrahādhyāya (concluding chapters).

The subject matter dealt with in the above eight section are funda mentals. diagnosis, specific features, human body, fatal signs, treatment, pharmaceutical and successful management.

Popularity of Caraka saṃhita

The Caraka saṃhita has been popular as the most outstanding and authoritative work amongst the Saṃhitas of Āyurveda.Though in early times there was a large number of saṃhitās on different specialities, at the time of Vāgbhata the Caraka-Saṃhita and the Suśruta-Saṃhita were the only texts representing the schools of medicine and surgery respectively. though Vāgbhata tried his level best to degenerate their authority in orde to establish his own footing, he could succeed. Only in getting his place after those two in the great triad. Vāgbhatas Aṣṭāṅga saṃgraha and Aṣṭāṅga hṛdaya based mainly on these two text.

The popularity of the Caraka saṃhitā continued to increase and it attracted many top ranking scholars to involve themselves as commentaries. Bhattara Hariścandra, Jejjata, Sudhira, Ìśvarasena, Cakrapāṇi etc. Wrote commentary on it.

The work became so popular and its demand was so extensive that it was translated in various languages from time to time. It transtated into perion, arabic, english. later on it was translated in Hindi, and various regional languages.

Footnotes

- ↑ I.P., Vol.I., p.1.

- ↑ H.I.L.,p.1-53

- ↑ C.S.I.P., p.175

- ↑ Ibid, p.176-182

- ↑ C.S.Su., 30.26

- ↑ C.S.Su., I.20

- ↑ C.S.Su., I.41.

- ↑ Îg.Veda., I.116.8

VI.16.5

VI.31.4

J.Fillozat, The classical doctrine of Indian Medicine trans. Dev Raj Chanana , p.6. - ↑ Some aspects of pre-historic technology in India, p.64.

- ↑ Fillosat, pp.56-59.

- ↑ H.I.P., Das Gupta., p.132.

- ↑ History of Chemistry and medieval India., p.37.

- ↑ H.I.P., Vol.II, Das Gupta.,p.290-291

- ↑ AtharvaVeda Saṃhitā.,X.2.13

C.S.Su., I.12.8