Reflections and Expansions on Buddhism’s Eight Stages of Mind

Some colleagues and I have recently been discussing the problem of how experimenters’ attitudes, both conscious and unconscious, may affect whether any psi actually manifests in their parapsychological experiments. This is a complex subject I won’t go further into here, but one suggestion was that a concept of eight stages of consciousness taught in some branches of Buddhism might be helpful in understanding this issue. As I have been struggling to fully understand that concept for some years, I thought it might be useful to share some thoughts about it here.

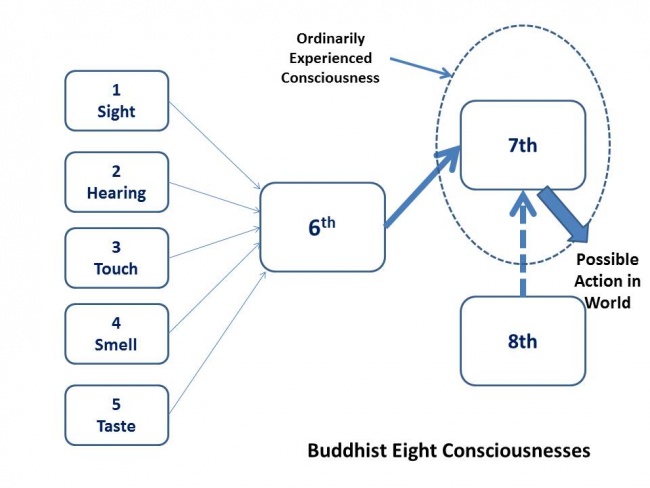

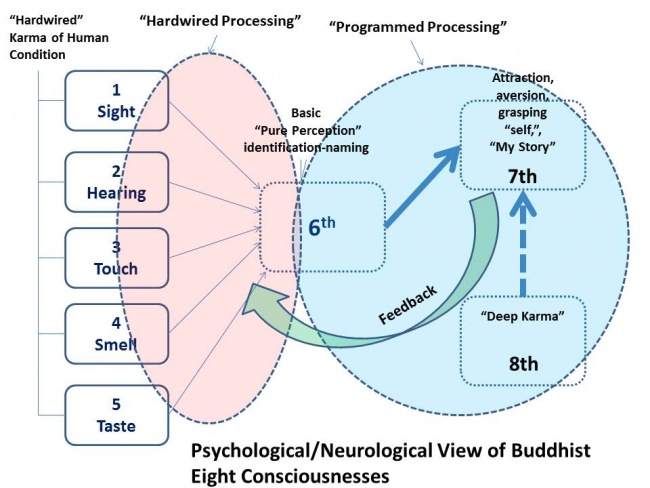

Figure 1 outlines a basic Buddhist conception of eight stages of consciousness. “Stages” tends to imply a serial progression, but that’s not fully the case here. Consciousnesses One through Five are the five classical senses, sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste. Those are what we would call in modern terms parallel inputs to consciousness, rather than separate stages of action. (There are other minor senses, such as balance, that I have not included here, but the five classical senses are sufficient for our discussion.)

The outputs of all of these senses feed into what’s been called the Sixth Consciousness. After an initial sense feed, we begin further sequential processing, for the output of the Sixth Consciousness feeds into the Seventh Consciousness, from which action may arise, and or output goes into the Eighth Consciousness. What we normally refer to as experiencing our own mind, experiencing our own consciousness, is almost wholly activity within the Seventh Consciousness, thus I have put an oval around it to indicate this in Figure 1.

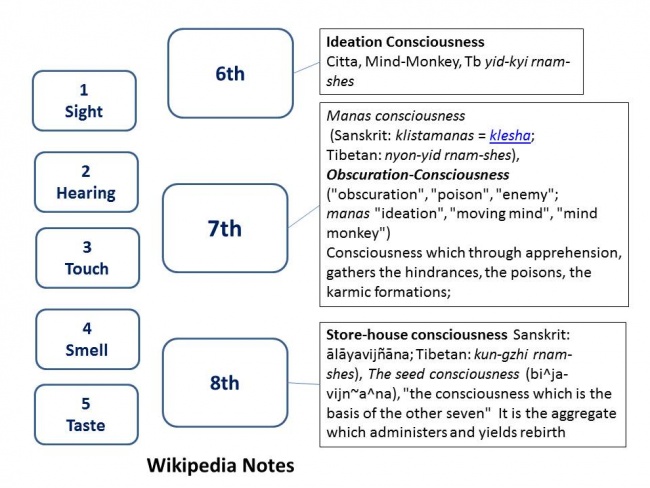

What are these stages of consciousness? In Figure 2, I’ve listed some classical Buddhist names and comments on the functions of these various consciousnesses, conveniently taken from a Wikipedia article, as modulated by my understanding of various teachings I’ve received from Sogyal Rinpoche or Tsoknyi Rinpoche or that a colleague (especially Dr. Serena Roney-Dougal) has communicated.

In Figure 2 I’ve bolded the term for particular stages of consciousness that I think is most useful for getting a quick idea of what it’s theorized as doing. I say “theorized,” incidentally, from my perspective as a Western scientist, but I should note that among Buddhists who are highly skilled in meditation, I’m sure these descriptions/names are more an expression of direct experience, direct observation of these processes, although undoubtedly tinged with theory to some extent. I have always been very impressed and admiring of the discipline and training needed to develop the observational skills to make such observations!

The Sixth Consciousness is called Ideation Consciousness. Its primary function is an instant recognition of what one or more of the senses is registering at a given moment.

The Seventh Consciousness, Obscuration Consciousness, is usually treated in Buddhism, as I’ve encountered it (see http://blog.paradigm-sys.com/740/ ), as if it’s the major source of all our suffering. As a psychologist, I tend to see Seventh Consciousness as an elaboration stage, connecting incoming sense impressions with previous knowledge and to our desires, etc., but Buddhism focuses on the way we create a false sense of self, which then gets constantly driven by the “poisons” of the mind, attachments, aversions, and ignorant, mindless habits.

As I mentioned briefly above, the activity of the Seventh Consciousness is primarily what we are conscious of. Thinking, remembering, feeling emotions, planning, etc. That can mean, at its worst, a constant “stewing in our own juices,” the constant play and replay and replay and replay of our neurotic fixations, etc.

The Eighth Consciousness, Storehouse Consciousness, is considered a deeper consciousness than the others, and apparently seldom directly experienced although it’s usually active in the background. It is the “seed,” the basis from which we have the ability to be conscious in other ways, and it constitutes very long-term memory, including the seeds of actions carried along from previous lives that may affect our current lifetime if the situation is appropriate for particular karma to ripen.

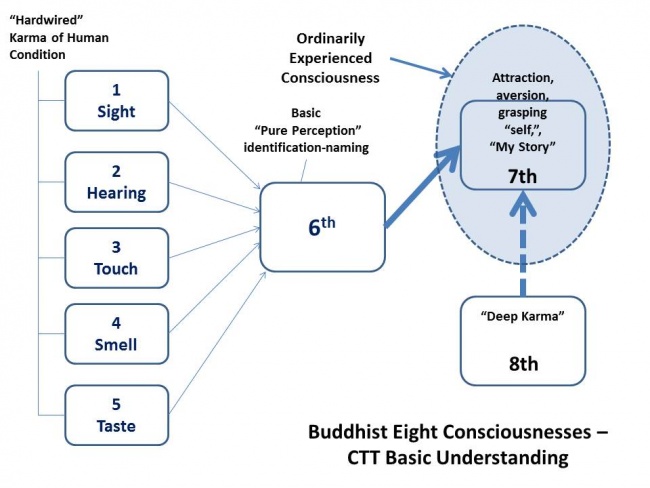

In Figure 3 I tried to put this in a simplified, modern perspective.

We begin with the inputs of the five senses, and I’ve indicated that they are, to use what is now a common computer term, hardwired. That is, our senses are physically built in ways that affect the quality of the information they detect, process, and send on to the Sixth Consciousness. By and large, there’s nothing you can do about their hardwired characteristics, that’s part of being human, the “karma” of the human condition. There are some exceptions, such as wearing corrective glasses if you have poor eyesight, or using a hearing aid if you’re partially deaf, but unless you’re a synesthete, you’re going to get visual sensations from your eyes, if and only if electromagnetic radiation within the certain wavelength range reaches them, etc.

The outputs of these five classical senses reach the Sixth Consciousness whose job is immediate recognition and identification of what we’re perceiving. Identification apparently includes the proper name of the object being perceived in teachings I’ve received. I look up and glance out my window now and see a tall green thing that I instantly know is a “tree,” I move my glance down and see what I instantly know is a “printer,” I look to the right and instantly recognize several objects along the wall that I know are “bookcases.” I’m aware of no effort in doing this, it just seems to happen automatically.

I have heard teachings that seem to characterize the activity of the Sixth Consciousness as “pure perception,” but I am not happy with the adequacy of that term. Insofar as “pure” implies that we have an absolutely accurate perception of whatever is in front of us, this is simply not factually true. (This is a fact that we have been able to discover through modern science, and which was far less available to the otherwise marvelous introspective observations of meditators.) Our sense organs have various kinds of information processing built into to their intrinsic operation, so even at the level of the Sixth Consciousness we have a selective, biased perception of what is actually out there, hardly “pure.” Our eyes, for example, have a built in neural process called lateral inhibition which increases the contrast, sharpens the edges of things that we see, instead of seeing the fuzziness that is actually there. Practically, this kind of edge sharpening can be very useful, it makes it much easier to see the tiger lurking in the bushes than would otherwise be the case! On the other hand, compared to the incredible changes that the Seventh Consciousness can create, reception in the Sixth Consciousness is indeed rather pure.

As mentioned above, the vast majority of what we experience as our consciousness, the activity of our mind, is the activity of the Seventh Consciousness. This could be very useful if you have the relevant knowledge and disciplined skills to, say, design a better airplane. But, as Buddhism recognizes so very well, much of the time we’re involved in telling ourselves our personal stories, our personal myths, so making ourselves relatively insensitive to what’s actually out there in our world. It also creates, among other things, lots of unnecessary and useless suffering.

If you’re a guest at a dinner party and are given strawberry ice cream for dessert, for example, but you really wanted vanilla ice cream, and sit there not enjoying what you actually have, remembering other times you’ve been disappointed, that’s useless and unnecessary suffering. If, when I was glancing about as above to illustrate the workings of the sixth consciousness, when I reached the sight of the bookcase I got involved in ongoing worries about what’s going to happen to my collection of technical books after I die, will the institution I hope to give it to actually be able to accept it, will instead the collection be broken up, making it relatively worthless, etc., etc., etc., I have wandered off into a relatively moderate instance of the Seventh Consciousness activity creating useless suffering.

I’m not going to say anything more about the Eighth Consciousness at this point, as that opens up such vast psychological territories that I would probably confuse the points I’m trying to make here…. :-)

The Eight Consciousnesses Map and Suffering

Given that life is often difficult and stressful, and there’s lots of unhappiness caused by real events as well as unnecessary psychological suffering, what can we do about it? When the Buddha was asked what it was that he taught, he told his interlocutor that he taught the end of suffering. How does this map of the eight consciousnesses help us escape suffering?

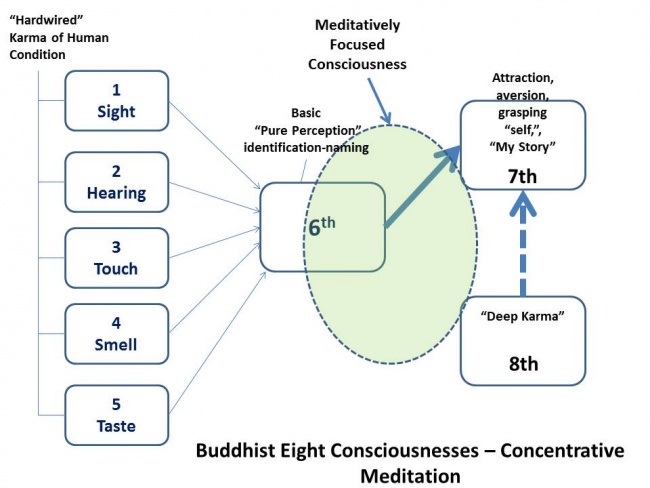

Our own personal experience, as well as various psychological studies, shows over and over again that there is only so much “mental real estate” available at any given time, only so much capacity to experience. If you fill that capacity up, there is no room for new experience, it’s hard for new processes to begin. If your mental real estate is already filled up with your Seventh Consciousness activity that creates constant suffering, it can be hard to simply stop those thoughts and feelings, become more rational, and stop suffering . In Figure 4 I’ve given a perspective on using concentrative meditation in Buddhist practice to diminish and perhaps eventually eliminate suffering.

The main way Figure 4 differs from Figure 3 is that I’ve taken the oval which designates where experience is focused, and moved it so it’s primarily in the Sixth Consciousness, hardly touching the Seventh or Eighth Consciousnesses. The basic instruction for concentrative meditation is to pick some discernible object, usually some emotionally neutral object like the sensation of breathing, and keep your attention gently turned toward it. You have to gently monitor the process also, so that when your mind does stray away to your worries, plans for what to do tomorrow, Seventh Consciousness stuff, etc., you relax these new contents and bring your attention back to the chosen object of concentration. The Tibetan Buddhist term for this kind of meditation is shamatha with support, the support being the sensation of breathing in this case, but any tangible object could be used.

To the degree that you keep your attention focused in the Sixth Consciousness, on the immediate perception or designated range of perceptions coming in through some sense gate, you simply don’t have much awareness or energy left over for the Seventh Consciousness to use in telling your story, running your worries over and over again, etc. It may be hard to learn to do this at first, but as you eventually get better at gently returning your attention to the support object, you spend more and more time there. The Seventh Consciousness process is starved of energy and attention, and you experience increasing degrees of peace. Meditators who get very good at this kind of concentrative meditation eventually experience a series of jhana states, which involve sensory withdrawal from the world and increasingly subtle states of peace and happiness. (I don’t really understand the jhanas from personal experience, though, so won’t say anything more about them here.)

Note that I am not saying, and neither does Buddhism as I’m familiar with it, that learning to remain in the jhana states, not having any thinking and feeling in the Seventh Consciousness, is all that there is to enlightenment. As noted elsewhere, I have been troubled by a strong anti-thought trend in Buddhism, but that’s not of concern to us here.

Psychological/Neurological View of the Eight Consciousnesses

Now let’s look at the scheme of the eight consciousnesses from the perspective of modern neurological and Western psychological knowledge. Figure 5 schematizes that.

As indicated earlier, there is a high degree of hardwired processing built into our senses, and almost nothing we can do about that. In terms of initial neurological processes that receive the data from the senses, though, there is also considerable hardwired processing. The fact that our vision is extremely sensitive to movement, even in the periphery of our visual field, for example, illustrates that. So I’ve shown hardwired processing as an oval that includes both the classical senses per se and the Buddhist Sixth Consciousness.

The large circle indicates what we might call programed processing, further neural and psychological activity which selects certain perceptions for enhanced attention, rejects other perceptions as unimportant, and transforms these already chosen perceptions into forms that meet with the needs and standards of our personality, our sense of self, our hopes, our fears, social propriety, etc. By “programmed,” I mean processes which were explicitly or implicitly created in us or taught to us, voluntarily or involuntarily, in the course of growing up. In contrast to hardwired neural processing, programmed processing can be changed. The current excitement about neuroplasticity is an expression of our happiness at the freedom we realize we now have that some psychological processes which have been incorporated into the very operation of our nervous system can be reprogrammed, are plastic. I have added an arrow labeled Feedback into the diagram to represent this neuronal plasticity, perhaps extending even a little into lower level sensory processes that we currently think of as hardwired.

As in an earlier figure, the large circle shows the sphere of activity of which we’re normally conscious.

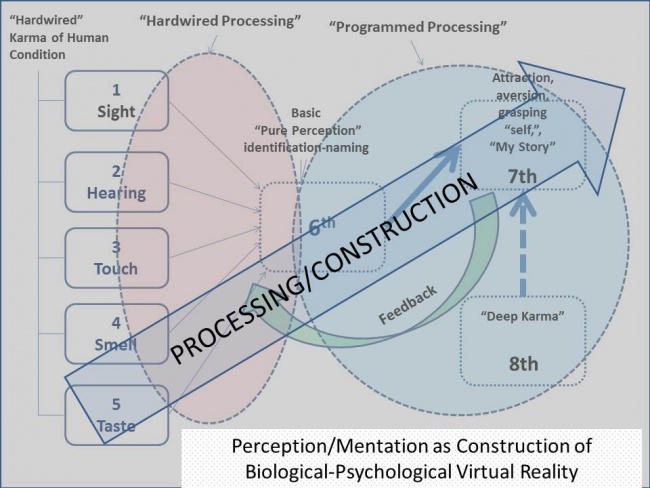

We humans like dichotomies. Something is yes or no, useful or useless, good or bad, and the Buddhist characterizations of the Eight Consciousnesses and my own earlier diagrams fit in nicely with the desire to dichotomize. But the reality, illustrated below in Figure 6, is more of a continuum with varying, increasing degrees of processing.

At the left-hand side of Figure 6 we have the inputs from our classical senses, and there is little processing, other than the hardwired processing which is part of the structure of the sense organs themselves. As we move more toward ordinary consciousness, though, I show a large arrow labeled as Processing/Construction, to indicate that the things we experience are more and more constructs, built up compounds, rather than “pure” perceptions or simple perceptions of sensory experience. The Buddhist division into discrete stages, then, is generally seen from this Western perspective as a simplification. That’s not to decrease its value in any way, though. It’s a roadmap to help you identify different aspects of your mental activity, and by identifying them have more conscious choice over what you want to happen to you, to move more toward enlightenment and away from living in samsara, Endarkenment.

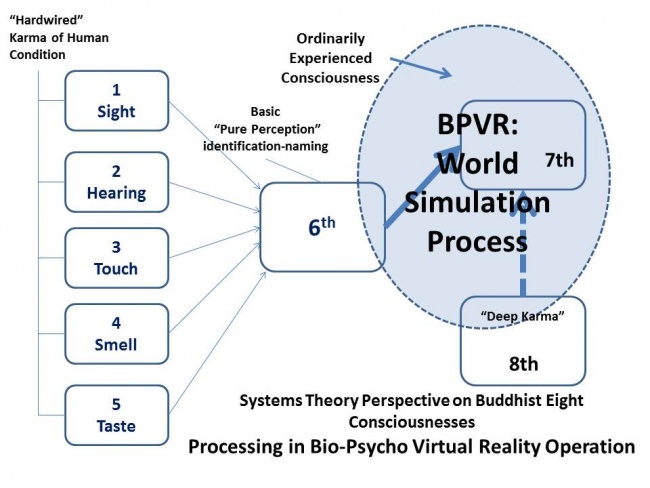

Biological Psychological Virtual Reality (BPVR)

Another way to express this increasingly construction of consciousness, this movement away from simple perceptions to more complex and interrelated concepts that are mistakenly perceived as if they’re simple perceptions, is to turn to my systems approach to altered states of consciousness, and to note that the end results of psychological and neurological processes is the creation of a Biological Psychological Virtual Reality, as illustrated in Figure 7, below. As mentioned briefly above, everyone has experienced a basic BPVR in the course of having a nighttime dream. There you find yourself in a world, events happen, characters enter and interact with you, time passes, and, except in the relatively rare case of lucid dreams, you do not question that this is reality. From our outside perspective you are in a virtual reality, a world that seems real, but is not real from our perspective. This BPVR of nocturnal dreaming differs in two very important ways from the BP VR of waking.

First, the quality of your consciousness is more passive, dumber, and duller than it is in the waking state. You don’t have a true apprehension of your actual state, namely that you are dreaming. You don’t have access to your accumulated life knowledge that would quickly show you that many of the events happening in the dream are markedly different from what customarily happens in waking life, which would alert you to the fact that it’s a dream. Indeed, in Buddhism and other spiritual systems, the lack of realization of our true state in nocturnal dreaming is often used as an analogy for our lack of realization of our true spiritual nature in the ordinary waking state. Thus what we call “waking” is a form of dreaming from a higher spiritual perspective.

Second, the world created in your nocturnal dream state is almost totally isolated from getting input from any sensory perceptions. It’s as if a roadblock was put up across the nerves that come from your sense organs (this is a function of the subsystem I’ve called Input Processing in my systems approach. While things may happen in the real world around you, they are not going to control the creation of the virtual world you experience yourself in an adaptive way. Sounds and sights are almost always totally ignored unless they are loud enough to wake you up, bring you out of the dream BPVR. On the relatively rare occasions when sounds do make it into the dream world, they are frequently distorted (the subsystem Input Processing again) so that they fit into the context of the ongoing dream in a smooth way that doesn’t disturb the basic creation of the dream world. The ringing sound of an old-fashioned alarm clock, for example, if it doesn’t wake you, may become a dream telephone ringing in the room you were standing in in your dream world.

And so…..

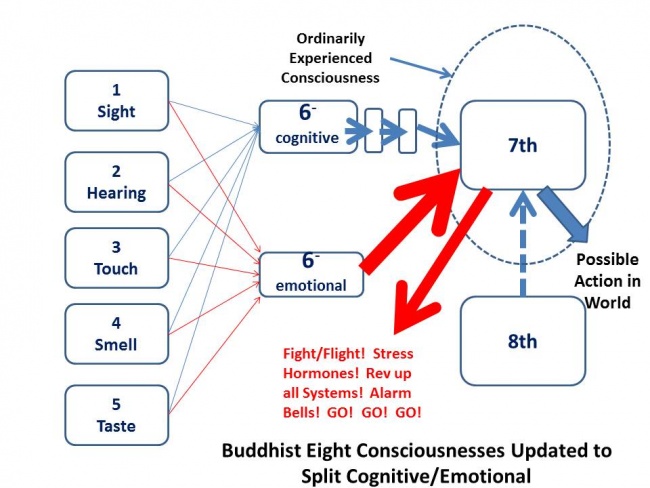

I’ll close with just one example of how adding in knowledge from another spiritual system and from modern neurology might substantially improve the usefulness of this basic map. One of my main personal sources of psychological and spiritual inspiration has been the teachings of G. I. Gurdjieff. Among his teachings was the concept that we have three basic kinds of intelligence, three “”brains” as he called them. One of these is the intellectual part of the mind/brain. The second was an emotional brain, and third a body/instinctive brain. Gurdjieff talked about how each of these brains had to be developed and educated in terms of its unique abilities, otherwise we end up, as is all too common (I speak, unfortunately, from personal experience), with one kind of intelligence highly or overly developed and the others undeveloped and probably neurotic. Thus much suffering in life comes when one kind of brain does the work that should really be handled by another kind of brain, for example the intellectual brain handling something that really requirs emotional intelligence. As part of these ideas, Gurdjieff taught that the emotional brain is faster than the intellectual brain: you may find yourself emotionally reacting to something before you intellectually understand what’s going on.

This faster speed of the emotional aspect of intelligence processes has been confirmed by modern neurological studies. This is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 8, below.

Something happens so your senses are presented with an event that has both intellectual and emotional qualities. If we now see the Sixth Consciousness is divided into specialized processes, one for handling emotionally neutral, primarily cognitive information, and the other for information that might be emotionally significant, there’s an interesting result. The intellectual processing, what I have labeled 6-cognitive in Figure 8 has a number of neurological steps, each one of which takes time, to get the information to the higher parts of the brain, the part of the brain/mind that’s going to assess the overall situation and decide what, if anything, needs to be done. The emotional processing part, however, while not as smart as discriminating as the intellectual part, can get its conclusions to the higher parts of brain much faster, there are fewer steps.

This makes sense. It’s much better to be afraid and run away instantly if something is moving in the trees toward you and it could be a predator, and then feel foolish when it turns out to be the wind, than to stand there doing a more detailed intellectual analysis when that time delay might let you get eaten by an actual predator!

To illustrate this with an analogy, you’re sitting in your study having an interesting conversation with a friend, and suddenly you feel very anxious, your body gets jumpy, you feel afraid and/or angry, you look out the window and see that your assistants have alerted the troops! They are arming and getting into battle formation, your escape pod is being readied, and loud alarm bells are going off and red warning lights blinking! QUICK, QUICK, DANGER, DANGER, ACT, NOW, NOW, NOW! You may try to think about this and realize it’s a tremendous overreaction to something of no real significance, but it’s very hard to think when your body is jumping, you’re full of emotion, and those damn bells are ringing!

I’ve informed many students about this difference in speed of the emotional processes, using this information drawn from both Gurdjieff’s teachings and neurology, and they’ve found that it’s helpful in dealing with their emotions. We so often take the blame for what we feel. “I’m a stupid person, afraid, angry, weak willed, etc., etc.!” This kind of reaction doesn’t help you cope well with actual situations. But with even a small intellectual voice remembering this knowledge, saying “Your feelings have probably been hijacked by the emotional brain, it’s probably not really that bad,” you have a more spacious mental state to calm down in.

To put it another way, the map of the eight consciousnesses is very helpful in giving you a wider perspective on your own mind. In this case, just remembering that there’s a specialized part of you which is designed to emotionally hijack you, that prefers to make mistakes rather than take a chance, helps you remember there is a bigger “you,” instead of just the part being drowned in the emotions. A big “you” observing one part of itself having emotions has many more possibilities than a small “you” which is drowning in the flood….

Source

By Charles T Tart

blog.paradigm-sys.com