Rinchen Terdzö (3)

The categories of outer, inner, and secret are classifications of practice in terms of the mind of the practitioner. They offer progressively more subtle entries into the depths of one’s nature. Traditionally, ‘inner’ is said to be what we can feel physically or internally as opposed to an experience everyone shares. For example, I feel my indigestion; nobody else does because it is an inner experience. The implication of ‘secret’ is that something is not obvious, rather than something secret that is deliberately locked away and hidden. However, all the practices presented in the Rinchen Terdzö are secret from the perspective that they are not taught to a student outside of the proper context. All of the guru practices are meditations that help develop the confidence that the wisdom and sanity of the teacher is also at the core of one’s own being.

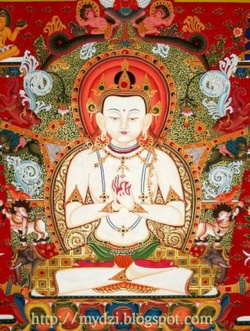

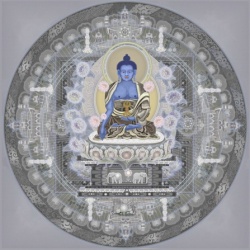

The inner practices of the guru in the Rinchen Terdzö are divided into three areas of emphasis, called the three kayas (Tib. ku). Kaya is a Sanskrit word, the honorific way to say ‘body’ or ‘form’. It is sometimes easier to think of a kaya as referring to an aspect of enlightenment instead of a body. The word kaya can refer to the body of an enlightened being, an empowered statue of a buddha, or an aspect of enlightened mind. For example, the practices in the section of the Rinchen Terdzö devoted to the three kayas of the inner guru emphasize either the ultimate essence of the guru, emptiness, as the teacher; the luminous nature of the ultimate essence as the teacher; or the compassionate display of the guru in this world as the teacher. These three kayas are respectively called the dharmakaya, sambhogakaya, and nirmanakaya, or in Tibetan, the chöku, longku, and tülku.

Tülku is also the word used to refer to a reincarnate teacher. In middle of the yesterday afternoon, there was a noisy commotion out on the veranda. No one in the front of the shrine room knew what it was. The whole room hushed, including Namkha Drimed Rinpoche. We all started shifting to look out the temple doors. For a moment I wondered if someone had died or had a seizure. After ten seconds of staring to adjust to the sunlight streaming into the building I could see waves of movement on the porch. People were running this way and that as a swarm of bees swept through the crowd outside. All of a sudden, dozens of people ran into the crowded shrine room and doors were being slammed everywhere. Total pandemonium! Namkha Drimed Rinpoche went into a deep belly laugh. The adventure with the bees continued throughout the afternoon until a sensible Tibetan layman filled a censer with lots of broken incense and made a big smoky offering out on the porch. Over the last three days Jigme Rinpoche was composing his letter about the Rinchen Terdzö.

During the morning reading transmission, I was called to the shrine room to quietly review my transcription of his text. Because it was a bit boring during the lung, any unusual occurrence got everyone’s attention. I received a close inspection by the entire monastic community as I worked on the letter with Jigme Rinpoche. The lay people outside got to make an assessment of me as I plodded my way through the crowd on the veranda to get to the side door of the shrine room for the meeting. Slowly the Westerners and Tibetans are figuring each other out, and the cultural differences are starting to melt into curiosity and warm smiles.

Before flying to India, I heard that a good head chöpön is essential at a Rinchen Terdzö. A chöpön is a master of offerings. This person maintains the shrine throughout the day and brings objects from the shrine to the teacher and then from the teacher to the students. For example, the very first part of an empowerment is a symbolic purification of the students as they enter the environment. This is done through the teacher’s blessing along with recitation of a mantra and drinking water from a ritual vase. The mantra used is that of Vajrasattva, the buddha associated with purity as well as being the unity of all the buddhas.

The vase water is consecrated by the teacher before the students enter the shrine room. Then the chöpön or an assistant serves the water to everyone as they enter the empowerment. The offerings, icons, and empowerment substances changed with every abhisheka, and the numbers of different objects needed to be set up for the next day sometimes numbered in the hundreds. The Rinchen Terdzö was so complicated, changing shrines and icons so often, that at least twelve assistant chöpöns were needed, one of who was solely responsible for keeping track of where we were in the multiple volumes of text that we jumped through during the course of the day.

Today we continued receiving the abhishekas for the inner practices of the guru. A computer malfunction slowed writing and preparations over the last few days and contributed to a feeling of being lost during some of this afternoon’s empowerments. Feeling lost isn’t new; it’s been inevitable given the complexity of the Rinchen Terdzö. Today’s confusion was complicated by two of our empowerments lists being in conflict about what was going on. I recall a story Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche told a few years ago. He was attending a long series of empowerments given by His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche.

The Sakyong said the entire front row of lamas could not find the page of the text they were on. They asked the chöpön who looked at them and said he didn’t know either. This meant that the only person who knew what was happening was Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. Fortunately, the main thing to do at an empowerment is to regard the teacher as a completely enlightened being, relax, and follow the teacher’s instructions about what to do next. Besides His Eminence and Lama Tenzin (the head chöpön), the person responsible for making sure we didn’t get lost was Lama Kunam, the chöpön in charge of keeping our place in the texts. Every few days we’d find ourselves paused during an empowerment while Lama Kunam rapidly flipped through a stack of texts at his seat.

Then he would suddenly jump to his feet with a few pages in hand and swiftly bring them to His Eminence at the throne. Lama Kunam, who accompanied Namkha Drimed Rinpoche in the West in 2008, was unflappable during these liturgical gaps, even with 800 people curiously looking to see if we missed a beat or not. Usually Tibetan texts are not as carefully indexed and footnoted as their Western counterparts, which was the main reason why Lama Kunam’s job was necessary. In the middle of a sentence it might abruptly read, “Finish as before,” and give no further instructions. His Eminence rarely missed a beat during the empowerments. Most days there was a moment when he redirected a chöpön who had fallen behind in bringing this or that vase or icon. However, the chöpöns did an amazing job throughout the Rinchen Terdzö. They continually helped each other, and they all exuded great respect for His Eminence.

Their sense of humor and light touch was always evident as was their incredible precision about what needed to be done and, most importantly, when it needed to happen. Within the section of the text that presents the abhishekas for the inner practices of the guru, today we reached the nirmanakaya guru, practices focused on the guru in the manifest aspect of compassion. Tonight the western students were supposed to have their first briefing with Jigme Rinpoche, but the abhishekas lasted two hours longer than expected, until eight at night, so the meeting was postponed until tomorrow.

Before I got to Orissa, I thought the guru section of the Rinchen Terdzö would contain only guru yogas—meditations where one visualizes the form of a teacher, such as Padmasambhava, and then supplicates the teacher for blessings. Such practices help increase the stability of the mind, along with opening one up to the good qualities of the teacher, qualities which are ultimately one’s own. This in turn brings out more of one’s natural appreciation and devotion to the teacher, to the lineage, and to buddha nature itself. I was surprised to learn how many practices in the guru section of the Rinchen Terdzö were not guru yogas.

There were many yidam and protector practices as well. Last night Jigme Rinpoche explained that in these cases the yidam practices were written from the point of view of guru yoga; the yidam is considered expressly an aspect of Padmasambhava. Thus, for example, the mantras for the yidams all have the mantras of Padmasambhava woven into them. Later we learned that other practices in this section were not necessarily guru yogas, but branch practices which were related to the guru yoga. An example of a branch practice would be a protector practice for a terma cycle to which a particular guru yoga belonged. The sequence of the Rinchen Terdzö isn’t simply a big list or a bunch of bins to pick things out of.

The ordering of the entire treasury of empowerments and instructions is itself a teaching on the evolution of how to practice in a profound and vast manner. The teachings move towards progressively refined practices that rely more and more directly on confidence in one’s own basic goodness. At the same time, the teachings present a complete array of methods to benefit others, particularly in the auxiliary sadhanas section much later in the collection. I think this is another reason why giving and receiving the transmissions of the Rinchen Terdzö is so meaningful for lineage holders to experience. It is a direct and subtle, deep and wide-ranging journey through the entire path.

For a lineage holder like Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, receiving the Rinchen Terdzö expands what he is able to offer others. While the Sakyong is very much a part of the West, he is also a big part of the East. The expectations of him are very great, not only because he is Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s son, but also because he is the rebirth of Jamgön Mipham, one of the most influential teachers in the Nyingma lineage. Through receiving the Rinchen Terdzö, the Sakyong becomes more able to bestow whatever transmissions are requested of him when he travels in Asia. People will have greater confidence in him and in their own heritage knowing that he upholds the heart practices of the Nyingma lineage.

Today we received more empowerments related to the terma called The Seven Chapters. This terma was revealed by a tertön named Ngari Panchen. He is most well known in the West for his remarkable book, Perfect Conduct. This text describes all the levels of conduct in the dharma, from how to be a dignified monastic or a lay person, to how to properly be a bodhisattva in whatever we do, and finally to how to be a fully realized tantric meditator. Ngari Panchen lived from 1487 to 1542, the period when the Europeans began to colonize North America. He was an emanation of the enlightened mind of King Trisong Detsen, the ruler who invited Padmasambhava to firmly establish the dharma in Tibet. In his early life, Ngari Panchen was something of a prodigy because he is said to have mastered and realized the teachings of the Nyingma and the later schools, as well as mastering what are known as the major and minor sciences.

This would be like getting doctorates in philosophy, religion, medicine, literature, and science all at once. Panchen, a title he received in his early twenties, means great pandit. A pandit is a title from the Indian tradition, referring to a very learned scholar-teacher. At the age of 21 Ngari Panchen started to meditate more intensively. He did retreats at many pilgrimage sites in Tibet and Nepal, and he received transmissions and teachings from both Tibetan and Nepalese gurus. He was a true renunciate, had few possessions, and never stayed in one place for very long. While in retreat, he had many visions of the deities he was meditating on. More importantly, he began having dreams and visions of Padmasambhava who bestowed empowerments and blessings on him. At this time he fully recollected his life as King Trisong Detsen. Even with all these incredible experiences it is of note that Ngari Panchen did not become very active as a teacher until he was 38. Up until then he concentrated on retreat, receiving teachings and transmissions, and realizing the meaning of all the meditation practices he had received.

When Ngari Panchen did begin to teach, he put a lot of energy into impartially helping the different schools of Buddhism in central Tibet. Only at the age of 46 did Ngari Panchen begin to reveal his termas. He was unusual as a tertön because he did not have a consort. Tertöns often have consorts, children, and possessions. It is rare for a tertön be a celibate monastic. However, it’s important to add that a consort relationship with a tertön is not ordinary because the consorts to tertöns are also highly practiced, realized meditators. The tertön and the consort find each other, so to speak, because of very strong aspirations made in earlier lives to help each other to revitalize the teachings. This is the case with both male and female tertöns, although female tertöns, like monastic ones, are unusual. Ngari Panchen passed away at the age of 56 after benefiting beings widely. His book, Perfect Conduct is still one of the main texts on the topic vows and conduct studied in the Nyingma lineage.

Yesterday a big change happened in the shrine room. Another wave of the Ripa clan arrived and the available space in the family seating area on the stage to the left of His Eminence overflowed. The little crowd made things more difficult for the chöpöns. Today we discovered that the Sakyong, the Sakyong Wangmo, and Lhunpo Rinpoche had all been moved to the other side of the throne, shrine right. Along with this, it was decided that the five main recipients should come to Namkha Rinpoche’s right side rather than his left. Later we learned that this was the place where His Eminence sat when he received the Rinchen Terdzö from the Vidyadhara. Because of the changes, the Westerners, who were also seated shrine right, had a better view of the Sakyong, Jigme Rinpoche, and the others when they received the empowerments. Often it was hard to keep up with what was happening during the Rinchen Terdzö because Namkha Drimed Rinpoche spoke quickly and none of us had the texts for the empowerments.

However, even without hearing the words, knowing the names of the abhishekas and the general structure of all empowerments helped us keep up with things in a basic way. For example, at the start of any abhisheka one retakes the refuge vows—the commitments to the Buddha as teacher and example, the dharma as the path, and the sangha as the community on the path. This, and other similar parts of the empowerments are easy to spot, and since we repeated the verses His Eminence said, it was easy to click in. The many symbolic implements, vases with bright colored scarves and so on, also gave clues about what was happening and what to visualize. During the start of the Rinchen Terdzö I developed a mental habit of letting the main recipients ‘go first’ when Namkha Drimed Rinpoche bestowed the different sections of the empowerments—the vases of water, small painted icons, and so on. I’d wait for the five main recipients to receive the symbol for whatever aspect of purification or wisdom was being emphasized, and then afterwards I did the corresponding visualization.

Initially, that seemed to be the way to go about things. They got their empowerment, I got mine, and that was it. But because of the shift in the seating around the throne, I was able to see how the Sakyong received the empowerments and my outlook changed. I don’t know exactly what triggered the change, but I noticed the Sakyong in his role as a student rather than that of a teacher. His body and actions were those of someone completely attentive and humble in the presence of Namkha Rinpoche. He was really soaking everything in, becoming an empty vessel in order to receive the empowerments fully. He was soft and gentle while being alert and strong. As I watched the Sakyong I thought more about relaxation and devotion. It became clear that while I was lucky enough to receive the Rinchen Terdzö, I was mainly in Orissa to witness the Sakyong. Seeing him receive the teachings, and particularly how he received them, I saw things about myself—where I held back and how I could open up more. I felt a bit weepy when I wrote this because it seemed like watching the Sakyong enabled me to drop some my ambition and my heart relaxed.

After the empowerments today, a friend made a similar observation about how impressive it was to see the Sakyong in the role of a student. By the way, there was a lot of humor on the stage. The soft-shouldered collisions in the midst of the principal recipients’ efforts to quickly and smoothly reach the throne have made everyone laugh at one time or another. The Sakyong regularly checked in on his students in the shrine room, and often he sent one or another of us a smile or some raised eyebrows for fun. Yesterday, the Sakyong noticed I was perking up my posture and playfully mimicked me. As he stood beside Namkha Drimed Rinpoche’s throne between empowerments, he pushed up his head and neck while briefly moving his eyes upward like he was looking at the sky. We both chuckled.

Today was a milestone. We received the empowerments of the Könchok Chidu, a set of abhishekas for practices of the guru, yidam, and dakini discovered by the tertön Jatsön Nyingpo (1585-1656). Like Ngari Panchen, Jatsön Nyingpo was one of the rare tertöns who were celibate monastics. The Könchok Chidu is one of the most widely practiced in the Karma Kagyü, while the Longchen Nyingtik is the terma cycle most widely practiced in the Nyingma. When the Vidyadhara Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche passed into parinirvana in 1987, his cremation was lead by His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche.

It took several weeks to prepare for the cremation, which was held at Karme Chöling in Vermont. At that time there were about five hundred people living mostly in tents around the center and another 2,500 came for the cremation itself. After the event, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche stayed at Karmê Chöling another ten days and started to teach on dzogchen, the highest teachings in the Nyingma school of Buddhism, as well as give the abhishekas for the Könchok Chidu, the Longchen Nyingtik, and Vajrakilaya, which is the most widely practiced yidam in the Nyingma and famous for removing obstacles.

These events were the start of the fulfillment of one of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s predictions that dzogchen would be taught at Karmê Chöling in the future. I was one of a handful of new students who were permitted to attend Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche’s empowerments in Vermont. His Holiness’ presence and the importance of the empowerments were so inspiring that I abandoned my vacation plans and travelled Halifax to receive the empowerments from him again later in the summer.

Today it felt like things were re-arising in a new cycle, at least from the perspective of my own life. Events from twenty-two years ago at Karmê Chöling were again unfolding before my eyes, except in this case, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s own lineage stream of the Könchok Chidu was being poured into the Sakyong. After a great deal of digging through files before travelling to India, I found the descriptions of the empowerments from 1987 in my files and brought them with me to Orissa. That we had empowerment instructions for only handful of the abhishekas of the Rinchen Terdzö was a strong reminder of the importance of translation for the future of Buddhism in the West.

With these descriptions, a few of us were able to follow exactly what happened today—not including an additional ritual that we determined was an extra empowerment to hold the lineage. Seeing the instructions in English made sense of several things that had already happened during the Rinchen Terdzö. For example, I was reminded that a text symbolizes both the teachings and the empowerment to teach. The whole day was filled with unexpected understandings. Early in the afternoon, we figured out that certain abhishekas were long, middling, and short variations of the same empowerment. The three-part empowerments weren’t specifically mentioned in some of the Tibetan language lists produced by the monastery, so we were getting lost every now and then.

The liberal interpretations of numbering explained why some descriptions of the Rinchen Terdzö said there were well over a thousand empowerments in the collection, and others said there were only six or nine hundred. At the end of the day, we sat beside a monk who had memorized the chants in the Ripa Monastery chant book. He was one of the best, and got us to all the right pages at all the right times. Up until this evening, Patricia and I had been going a bit crazy trying to get help from nearby monks who usually didn’t speak English and weren’t up to speed about what was happening. Tonight, we left the shrine room with a fistful of post-its in our chant book, and even though we were still full of questions, we were happy to have learned that the Sakyong’s longevity chant was about fifth in the sequence of the twenty chants that concluded the day.

The first time I visited the Potala Palace of Dalai Lamas in Lhasa I didn’t know much Tibetan history, was thus surprised to see a long shrine hall in the Potala devoted to large statues of Padmasambhava, the eight Vidyadharas who taught Padmasambhava the Eight Logos, and Padmasambhava’s eight principal manifestations, such as Dorje Trolö. The hall looked more Nyingma than Gelugpa, the school of the Dalai Lamas. Generally speaking, the Gelugpa put less emphasis on Padmasambhava than the other schools of Tibetan Buddhism, especially the Nyingma. That was when I learned that there were Dalai Lamas other than the present Dalai Lama, His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso, who had a strong connection with the Nyingma School. Today we had an empowerment for a pure vision revealed by the 5th Dalai Lama, Lozang Gyatso. He was born in 1617 and was said to be the emanation of the enlightened activity of King Trisong Detsen as well as being the embodiment of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion.

At twenty-one he took full ordination and was already extremely learned, having mastered the classical curriculum. Lozang Gyatso studied impartially with masters in many traditions including the Nyingma. The 5th Dalai Lama had disciples from all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism. There were prophecies that the 5th Dalai Lama would find both termas and pure visions. When he visited Samye, the first monastery in Tibet, there were auspicious circumstances for him to find termas, but the conditions didn’t fully mature and so he did not reveal any. However, he later had visions and empowerments from the three roots (guru, yidam, and dakini) and he wrote these down, along with his own commentaries, in a text called The Twenty-Five Sealed Pure Visions. Several of these practices are included in the Rinchen Terdzö. Today’s Bringing The Essential Power Of Amitayus was the first. Amitayus is the buddha who confers long-life, and in this case was presented as a manifestation of the guru, the first root. The 5th Dalai Lama is also known for his many political achievements.

He built the Potala Palace, one of the most impressive buildings I’ve ever seen. He had great power because Mongol Gushri Khan took over most of Tibet and gave all civil and religious property to him. Later the Dalai Lama went to Beijing where the emperor venerated him and began a patronpriest relationship. The 5th Dalai Lama ruled both Central Tibet and the eastern region of Kham. In 1682, Dalai Lama Lozang Gyatso passed away at the age of sixty-one. The 6th Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyatso (1682-1706) took birth in a family descended from the tertön Pema Lingpa. Though not included in the Rinchen Terdzö, the 6th Dalai Lama is very famous for his poetry. In fact, the manager of our guesthouse was reading some of the 6th Dalai Lama’s poetry to us a few nights ago. The 6th Dalai Lama was the only Dalai Lama who was not a monastic. He had many girlfriends in Lhasa and was fond of chang, Tibetan beer. He had his girlfriends’ homes in Lhasa painted yellow, and some remain that way even today. His poetry mixes devotion, dharma, love, and longing much in the style of the poetry of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

The other evening we added an especially lengthy prayer for the activity and longevity of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. This came about the time we heard that His Holiness had accepted the invitation to formally open the monastery. It was hoped that he would come during the Rinchen Terdzö, but as it turned out the formal opening of the monastery occurred a year later, in January of 2010. Last night I noticed many of the littlest monks had already memorized the longevity supplication for Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche that was written by Namkha Drimed Rinpoche. I was told this had been a class assignment. Seeing the tiny monks belting out the Sakyong’s longevity chant from memory was amusingly embarrassing. I had not memorized the chant in English or Tibetan.

Last week the Sakyong invited me to his sitting room for a short meeting. He said that he was eager for me to speak with Jigme Rinpoche about a conversation the two of them had with His Eminence the day before. Namkha Drimed Rinpoche had spoken of how the Rinchen Terdzö was going, the connections between his family with the Trungpa Lineage, and how His Eminence had come to Orissa many years ago. I met with Jigme Rinpoche today during the morning reading transmissions. I sat beside him on the stage while his brother, Lhunpo Rinpoche, was giving the lung. Walker Blaine (WB): Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche asked me to ask you about what His Eminence said about how the events were going. Rinpoche mentioned that His Eminence was very happy, that he talked about the local deities being happy, and about the special circumstances we are in.

The Sakyong wanted me to see what you could say about that. Jigme Rinpoche (JR): What His Eminence feels is that this Rinchen Terdzö is happening at a very particular time of his life. That makes him extremely happy and satisfied because with his advanced age and very busy schedule he feels it is better done now than to wait. At the same time he feels that things have to develop in a very natural, spontaneous way. He sees that without any particular effort, things just seem to have happened. He is extremely happy to see that lots of positive things came together in order for this Rinchen Terdzö to happen at this monastery. For example, the site of the initiations was completed just in time so it could host everybody who is here. His Eminence is also very happy that the Sakyong is now receiving the Rinchen Terdzö, the lineage transmissions that he so deserves to receive.

His Eminence is giving him what he has actually received from the Sakyong’s father. He has been a kind of custodian of this precious lineage transmission. And so he is very happy to give it back to the rightful heir. Also there is the lung, the oral transmission. It wasn’t really planned. Somehow it happened at the last minute. We were not so sure my brother Lhunpo Rinpoche could come because of his travel documents. But it just happened at the last minute that everything worked out very well. His Eminence is very pleased to see that both the wang and the lung are happening at this place. Then, we have the monastic community from Nepal gathered here with the community from Orissa. It is important for them to receive these transmissions. Our main practices here and in Nepal, as well as in Tibet, are very linked to the terma teachings.

So it is so important that the practitioners receive proper transmissions of wang and lung. So they are benefitting from this, as are the students from the West. Another reason Rinpoche says he is happy is related to Orissa being a very important tantric place. The teachings happening here have a special significance in relation to the local deities, in relation to the energy, the natural elements. All of those things become conducive; the whole atmosphere is once again renewed, restored, recharged. This is because it is a place where so many of the siddhas4 actually obtained accomplishment. Siddhas have attained accomplishment by meditating in powerful places like Orissa. So he is just very happy about how the whole thing is progressing. WB:

The Sakyong also mentioned something about the 10th Trungpa [Chökyi Nyinche] having a connection with your grandfather. JR: Yes. The other day my father was telling me that in a way, what is happening now has to happen. It has to happen because he feels that there was some kind of seed planted as far back as the time of the 10th Trungpa. The 10th Trungpa requested the Rinchen Terdzö from my grandfather during a visit to Tsawa Gon. Tsawa Gon is not so far away from the center of the Ripa monasteries. This is also the region where my father received the Rinchen Terdzö from the 11th Trungpa. WB: Is that near Yak Gompa, where the Vidyadhara bestowed the Rinchen Terdzö? JR: Yes, Tsawa Gon is near Yak Gompa. So, the 10th Trungpa sent a message to my grandfather, Jigme Tsewang Chokdrub, saying that he would like to receive the Rinchen Terdzö from him. Unfortunately, my grandfather was not well at that time.

So this could not be completed as wished by the 10th Trungpa. My father feels that event sowed a seed where a time of teacher-student relationship would take place between the Ripas and the Trungpas in the future. And this is exactly how it has happened. When the 11th Trungpa was going to give the Rinchen Terdzö at Yak Gompa, my father immediately went because he had heard about the 10th Trungpa’s wish from my grandfather. There was always something. Trungpa was already in his mind, and so my father went to receive the Rinchen Terdzö from the 11th Trungpa. He was the main tülku recipient in the sangha at that event. And now he is giving it back to the Sakyong, the son of the 11th Trungpa. It’s as though things had been planned this way for many years. WB: The Sakyong said there might be more to be known about the Vajrayana connections with this area.

You talked about Odibisha to the Western students and 4 Someone who has attained siddhi. also in your letter, but the Sakyong was saying something about the proximity to Bihar and Bodhgaya. Is this another theme that your father considers significant? JR: Well, when my father was escaping from Tibet with all the great lamas, including the previous Dzongsar Khyentse and Dudjom Rinpoche, many of the lamas had a prophecy and a vision to go to Pema Kö. Pema Kö is a bay-nay, a hidden sacred place blessed by Guru Rinpoche. It was foretold in prophecies contained in several of Guru Rinpoche’s texts that in the degenerate time when the whole country would be taken over by the barbarians, one should proceed towards this bay-nay, Pema Kö.

So, when the Chinese actually invaded Tibet, every lama had one mind to go to Pema Kö. Pema Kö is on the border to India. My father went to Pema Kö and many other lamas met there. That place actually provided a temporary relief to the people on the run. Even though the rest of the country had been already taken over by the Chinese, somehow Pema Kö remained untouched for some years. And this is how many of the lamas could actually breathe. They could regain their health, regain their practices.

It provided a temporary home. While staying in Pema Kö, it was very clear that it would not remain safe forever. At that time, my father began to have visions of Odibisha [the tantric name for Orissa] as the next place to go. For a tertön, for him, it is important that wherever he travels, wherever he lives, it is a tantric power place like Pema Kö, Odibisha, or Bhutan. His Eminence spent several months in practice at Taktsang, Bhutan, and there he revealed many terma teachings. Odibisha is mentioned in many of the tantric texts as a power place. But additionally, my father has a particular link to Odibisha because he had a prophecy to go to Odibisha. That’s how he came to Orissa with the rest of his people.

After arriving here, he began to see many signs, many visions of past siddhas, as well as the local deities. And he also saw that Orissa still has many hidden places. It still has many hidden practitioners, who are not visible to common people. He feels that the actual practice lineage of tantra continues in Orissa uninterruptedly from the time of the Buddha. Actually, Orissa’s local historians claim that Orissa is Uddiyana. There is a lot of material to support that, which claims this is the actual place that was Uddiyana. There are now towns and cities here named Uddiyana. Also, there’s a history of Indrabodhi’s kingdom being in this region. The Indian historians believe that Padmasambhava was actually born in Orissa. There’s a book being written on that. The archeological excavations in Orissa almost all support this; all the artifacts are from the tantrayana. These are vajrayana deities that are not common in the rest of India.

For example, we have the 64 Yoginis Temple where you can go and you see all the footprints of dakinis all over the rocks. This is where they were supposed to have danced during a tsok, a ganachakra [a tantric feast). You can see the footprints of the dakinis. The 64 tantric yoginis’ footprints really are imprinted on the rocks. And there you can see a really beautiful, powerful stone statue of Vajravarahi dating from the 10th century. WB: I wanted to confirm that the two lineages of the Rinchen Terdzö that His Eminence holds are from Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and from the Very Venerable Kalu Rinpoche. JR: And there is a third from his father, Jigme Tsewang Chokdrub. He was actually very young when he received it from his father, he must have been around five years old. That’s the first time he received the Rinchen Terdzö, from his own father. WB: Thank you.

When the Vidyadhara bestowed the Rinchen Terdzö the second time in Tibet, there were about three hundred people present. That’s less than half the number here. The Sakyong remarked that since there were fewer people at Yak Gompa it would have been easier to hear the empowerments. He added that the people who most need to hear everything are those being empowered to carry on the transmission. It’s been amazing that everyone at the empowerments has been able to listen to His Holiness during the day.

Somehow an auxiliary generator has carried us through all the power failures during the Rinchen Terdzö thus far. This afternoon I found myself on the upper floors of the monastery during the midafternoon break. It’s a pleasant place to visit because there is a spacious gallery that looks down on the shrine room through big glass windows. I had wanted to ask a question of Jigme Rinpoche, but suddenly a kusung appeared and said, “The Sakyong can see you now.”

He must have thought I was seeking an audience with the Sakyong. It was a natural mistake since all the main rinpoches were staying on the same floor of the monastery. Seizing my good fortune, I went into the Sakyong’s small audience room. He was seated on his couch, relaxing during the break. Every time I’ve had a chance to speak with the Sakyong since the start of the Rinchen Terdzö, I’ve found him to be content, happy, and eager to chat. One meeting last week dwelled on his excitement about the Shambhala Lineage tree. He showed me photos of Noedup Rongae’s sketches along with photos of the Rigden statues in the Gesar palace in Golok, Tibet. The Sakyong mentioned the Tibetan statues were more nirmanakaya in manifestation than what would be in the thangka. During my brief visit this afternoon, the Sakyong spoke to me about how the Rinchen Terdzö was progressing.

Toward the end of our conversation the Sakyong said, “He’s crying.” I asked the Sakyong what he meant, and he replied that His Eminence had been crying during the last two days of empowerments. During one abhisheka yesterday, we stopped for a few minutes while His Holiness wept. A moment after he told me this, the Sakyong had to return to the empowerments. I stood alone for a moment, speechless and contemplated what His Eminence has been through, and how the great treasure he was giving to the Sakyong, the Ripas, and the all the sanghas represented in Orissa. We sit on the edge of a major transition between the generation of great teachers who left Tibet in the 50s and 60s and the present generation of teachers, who have entered a world very different from their predecessors’. This transition is so important for this world and the dharma. I have been making aspirations that the Sakyong be able to absorb as much as possible during this retreat.

Today we began the second week of empowerments for the inner peaceful practices of the nirmanakaya aspect of the guru, the practices that put the most emphasis on the manifestation of the teacher as the display of compassion. During the Rinchen Terdzö in Orissa, a second Rinchen Terdzö was offered in Dehradun, North India. Kyabje Taklung Tsetrul Rinpoche bestowed the empowerments. Taklung Tsetrul Rinpoche is the head of Dorje Drak, which is one of six main Nyingma monasteries. This monastery is the main Tibetan seat for the Northern Termas discovered by Rigdzin Gökyi Demtruchen. His Eminence Namkhai Nyingpo Rinpoche bestowed the reading transmissions.

The principal recipients of this transmission of the Rinchen Terdzö were the rebirths of Their Holinesses Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche and Dudjom Rinpoche, Khamtrul Rinpoche, and a host of other young reincarnate teachers, along with a great many lamas, khenpos, monastics, and lay sangha members. Her Eminence Mindroling Jetsün Khandro Rinpoche, the daughter of Kyabje Mindroling Trichen Rinpoche was the sponsor of this event.

When hearing or reading about the activity of amazing beings one is humbled. This is especially true when learning about Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye, whose activity and intellect seems almost superhuman. His vision was so vast and his desire to benefit so strong that after he passed away he took many simultaneous rebirths. Two of them—Shechen Kongtrül and Palpung Kongtrül—had direct connections with Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. Shechen Kongtrül was one of the Vidyadhara’s main gurus, and Palpung Kongtrül gave Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche his monastic ordination. Their names reflect the name of the monastery that the rebirth was connected with. Shechen and Palpung were the two main places where Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye stayed and taught during his life. As an aside, it is significant that three of the Vidyadhara’s main teachers—Shechen Kongtrül, Khenpo Gangshar, and His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche—were successive abbots of the Shechen monastery shedra or monastic university.

The founder and first abbot of the shedra or monastic college at Shechen was Jamgön Mipham, the Sakyong’s predecessor. Shechen Monastery at the time of the Vidyadhara’s youth was like Oxford or Cambridge, a great university that everyone aspired to go to. Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye was born in 1813. His father, or as we’d say in the West, the stepfather who raised him, was not a Buddhist, but a practitioner of Bön, the native religion of Tibet. Historians suspect this influenced Jamgön Kongtrül’s non-sectarian approach. He genuinely wanted to find the heart of every tradition along with preserving what was unique in each tradition. As a child he loved to dress like a monk and played by performing rituals. He learned the alphabet as soon as he saw it. Details like these are seen differently in the Buddhist world. For example, being able to read with little effort is not a sign that a child is simply smart or naturally gifted.

It means that the child has inherited strong positive habitual tendencies and aspirations from prior lives. As a youth, even before he’d practiced intensively, Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye had great faith in Padmasambhava and saw him and other great teachers in his dreams. He was well liked because of his gentle demeanor. When Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye was sixteen, a local chieftain who was his employer sent Jamgön Kongtrül to Shechen Monastery to study with a guru there named Shechen Öntrul. This was before the arrival of Jamgön Mipham Gyatso, so there was no shedra even though it was a famous monastery. While at Shechen he studied a great many topics and soaked them up quickly. At this time he began receiving empowerments and teachings on terma. This was, and still is, quite normal at any Nyingma institution.

The Könchok Chidu, which His Eminence bestowed the other day, was among the first termas Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye received at Shechen. Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye took full ordination at the age of 20, and at 21 the local chieftain who’d sent him to Shechen insisted he go to Palpung Monastery. Palpung was presided over by the great Kagyü teacher, Tai Situ Pema Nyinche Wangpo (1774-1853). Öntrul Rinpoche sent Jamgön Kongtrül to Palpung with the advice, ‘Don’t become sectarian.’ At Palpung Jamgön Kongtrül furthered his studies immensely and received many, many Kagyü and Nyingma teachings from Situ Pema Nyinche Wangpo and other teachers.

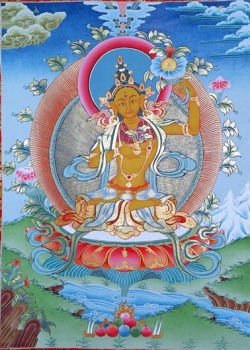

By this time he had also begun to study medicine. When requested what meditation deity would be best to practice, Situ Rinpoche told Jamgön Kongtrül to practice White Tara, the feminine aspect of compassion with a strong connection with long-life and vitality. After this, Jamgön Kongtrül had a very successful retreat on White Tara in the Jonang tradition. Although the Jonang School of Tibetan Buddhism was thought destroyed by the Cultural Revolution, in recent years several Jonang monasteries were found to have survived the devastation in Eastern Tibet. By his mid-twenties Jamgön Kongtrül had done many retreats on a variety of yidams and had begun teaching. He was such a good scholar that the 14th Karmapa, Thekchok Dorje (1798-1868), insisted that Jamgön Kongtrül teach him Sanskrit.

His name, Kongtrül, came from being recognized as the rebirth of a former student of Tai Situ Rinpoche, named Kongpo Bamtang Tulku. The prior incarnation’s name became contracted to Kongtrül by using the first syllables of the first and third names. Kon is short for Kongpo. Trul (with a pronunciation change) is short for tülku, which means emanation or enlightened manifestation. Lodrö Thaye means Limitless Intellect, and is the name Jamgön Kongtrül received when taking the bodhisattva vow, the vow to liberate all beings from suffering. Jamgön means gentle protector and is a name for Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom. In his late twenties, Jamgön Kongtrül started a long retreat in a hermitage above Palpung. It began as a three-year retreat, but soon extended to the rest of his life. He only came out of retreat in order to teach, join intensive group practices, mediate in wars or disputes, or in order to benefit beings in some specific way.

Although they’d met about eight years earlier, Jamgön Kongtrül and Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo began working intensively together around the time Kongtrül was 36 years old. They both had the same desire to go beyond the sectarianism that had caused the deterioration of understanding and good relations between the many different schools of Buddhism as well as between Buddhism and Bön. Together with Chogyur Lingpa they collected and exchanged whatever teachings they could. Though the seeds were already present in the unbiased attitudes of their teachers, the relationship between Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye and Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo formally began the Rime movement, a renaissance of unbiased teaching and transmission that continues to this day. For many years Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo urged Jamgön Kongtrül to create the Five Great Treasuries.

These original texts and collections preserve the essence of the vast dharma traditions of Tibet, and are the quintessential expression of the Rime movement, no pun intended. The Rinchen Terdzö is the largest of the Five Great Treasures. In the West, the best known of the five is the Treasury Of Knowledge. It is a massive ten-part presentation of all objects or topics one could learn about in the dharma, starting with the variety of Buddhist cosmologies and moving from there to describe the appearance of the Buddha, the various schools of dharma, the classical sciences, and all aspects of training from entering the teachings up to the fruition. Everything is described in an appreciative way from multiple perspectives. The last three of the Five Great Treasuries are the 8-volume Tantric Treasury Of The Kagyü Vajrayana Instructions, the 18-volume Treasury Of Spiritual Advice, and the 20-volume Treasury Of Extensive Teachings. Two of Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye’s other major works are The Compendium Of All Sadhanas and The Compendium Of All Tantras. Jamgön Kongtrül also wrote a large number of smaller works, some of which are also very influential. We will pick up on Jamgön Kongtrül’s life in a later entry.

Here is a picture of the shrine hall, the way it usually looked just after His Eminence had seated himself before the abhishekas started. At the time of the photograph there were nearly fifty Westerners in the room, more than usual because of arrivals for the Ripa community’s annual Dzogchen Retreat, which was planned to coincide with the Rinchen Terdzö. More guests were expected in the coming days. The Dzogchen Retreat went through a metamorphosis when it became possible to have the reading transmission along with the empowerments. At first, it seemed that visa complications would prevent Lhunpo Rinpoche from attending the Rinchen Terdzö. At that point, the plan was for the Dzogchen Retreat to have talks in the morning before the abhishekas in the afternoon.

However, when Lhunpo Rinpoche got his visa at the last minute, the lungs became possible, and the Dzogchen Retreat talks were shifted to the evening after dinner and the empowerments. People coming for a short time were encouraged to do their daily practice in the mornings rather than attending the lungs. Tibetan culture is impressive in the way that it works from the top down. We started with a general, but ragged, sense of quiet a few weeks ago. Then, in the last few days, the noise got out of hand with a babbling toddler and an upwelling of chatter from the young monks in the shrine room and the lay people on the veranda.

At that point, Namkha Drimed Rinpoche sharply addressed the issue during a talk at the end of the day. After that, the rinpoches and senior teachers also became more direct, and the sangha members camped out on the veranda became noticeably quieter. The process reminded me of how Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche worked with energy getting out of control at his programs. He let unbalanced situations get to the point where everyone saw them clearly, and then he’d abruptly cut in and start fresh. In the photograph above, I spliced six photos together to show the view of the shrine room from my seat. You will see that a big red curtain is drawn shut around the empowerment shrine.

This is because we had not seen the mandala yet. Mandala is a word that can refer to a complete representation of the world, the world itself, or a self-contained environment that is like its own world. For example, we could talk about the mandala at the Ripa House, the guesthouse next to the monastery. This mandala included the guesthouse building itself, Jigme Namgyal (the hard-working manager), Tashi and Suraj (the cooks), the three young women from the village who helped with chores, the various Ripa and Shambhala sangha guests, and Ruby (Jigme Namgyal’s four month old puppy who barked a lot when she was alone). Those were the main components of the guesthouse mandala. In the case of an empowerment, there are several mandalas. The most obvious one is on the shrine. The shrine mandala is a symbolic presentation of the various attributes of a meditation practice: the deity, its retinue, symbols of the mind in meditation, and so on. Several shrine mandalas were readied before the start of each day during the Rinchen Terdzö, one for each empowerment.

Every one of these mandalas was a symbolic representation of how the world appears to awakened mind. Just as there are as many ways to see the world as there are people, there are countless different mandalas to depict an enlightened vision of the world. In an empowerment, the mandala is often concealed until the teacher has symbolically entered the students into that particular meditation practice. At that point, the shrine will be displayed. Then the teacher explains the mandala in detail and brings the practitioners from the initial entry into the teachings to final stages of the path. An excellent explanation of a shrine, its symbolism, and their relationship to a practice can be found in the presentation of the Vajrayogini mandala in Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s book, The Heart Of The Buddha.

The final Dzogchen Retreat guests arrived today. The total number of Western students grew to about sixty and made a formidable block in the shrine room. Most of that number came from the Ripa community in the West. There were about fifteen Shambhala students in Orissa for the retreat. Three of them were late arrivals who stayed until the end of the Rinchen Terdzö: Jinpa, a Western monk from Gampo Abbey who came to serve as the Sakyong’s kusung in the monastery; Theresa Laurie who arrived during the second abhisheka on the first day; and Alexandra Kalinine who came to Orissa three days ago. Shambhala sangha members, Frank and Katrin Stelzel from Köln, and Siobhan Pathe from Hamburg, came to India to attend the Dzogchen Retreat itself. During the first weeks of the Rinchen Terdzö it was difficult to sort out what empowerments would happen each day. To know what was happening, we relied on a list written for the Rinchen Terdzö that His Holiness Penor Rinpoche bestowed in 2001.

This list did not always mirror what happened in Orissa, so we amended it based on a digital photograph of the Tibetan list that the monastery posted each day. Usually we were able to sort out the differences before the empowerments started each afternoon. However, today we realized something was greatly amiss because His Eminence started a series of fifty abhishekas that had been omitted at Penor Rinpoche’s Rinchen Terdzö. All of these empowerments were based on termas found by Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye. The 15th Karmapa, Khakyab Dorje (1871-1922), authored their empowerment rituals. I am not sure, but I think these termas were discovered when Jamgön Kongtrül was in his sixties, just after he first bestowed the Rinchen Terdzö. Later we learned that it was possible to condense certain related empowerments and that this was what Penor Rinpoche had done; fifty had been condensed into one empowerment.

A talk by Jigme Rinpoche this evening proclaimed the start of the Dzogchen Retreat. Usually the Padma Ling’s annual winter retreat is held in Europe, but because of the Rinchen Terdzö, the winter retreat was moved to Orissa. This may be the first group retreat joining our sanghas on Ripa land, just as 2008 Gesar festival at Dechen Chöling was the first group retreat joining the sanghas on Shambhala land. During the opening talk we learned that Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche would give a presentation later in the program. Jigme Rinpoche also announced that Lhunpo Rinpoche would make his teaching debut during the Dzogchen Retreat too.

The news came as a pleasant surprise because I had been wondering what Lhunpo Rinpoche would be like as a teacher. The Dzogchen Retreat teachings were given after dinner in the main shrine room at the old monastery complex, which is about a minute’s walk from the new monastery complex. The old two-story shrine building is small and stands in a shaded compound with some of the early monastic quarters making a little square around it.

It’s a peaceful area and a reminder of the humble beginnings for the Tibetans who had fled to India. The old main shrine room is actually the second one built by the Ripas in Orissa. The original temple had bamboo walls, a corrugated steel roof, and an earthen floor. The shrine room itself took up most of the building. The room was thirty-feet on each side with four columns in the middle that enabled a gallery to let in light from above. In front, behind a wood framed glass panel, was the same motif of statues as in the main temple: Shakyamuni Buddha in seated meditation flanked by Thousand-Armed Avalokiteshvara on his left, and Padmasambhava on his right.

These statues were carved and painted simply. They filled the space with a gentle radiance. The walls had no frescoes, and everything was slightly faded from decades of candle and incense smoke. It was like a shrine room in Tibet except that much of the structure was built with concrete, rather than with wood and rocks. How difficult it must have been for Namkha Drimed Rinpoche and his disciples to leave home with such finality and then to rebuild everything here. The Padma Ling sangha at the Dzogchen Retreat was an international group. The students came from Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Canada, the United States, and Russia. The packed shrine room also included English-speaking practitioners from Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan. Before Jigme Rinpoche arrived, preparatory remarks were made in French, Spanish, and English. The sound system included additional equipment for simultaneous French and Spanish translation. Several students eagerly awaited the start of the talk with sparkling blue earphones in hand.

During his welcoming remarks, Jigme Rinpoche said that much of what he wanted to tell us was already included in the letter he sent out last week, but he added a few points of interest. He said that one of the main conditions that made an empowerment possible was the fact that all of us have buddha nature within us. An abhisheka does not add anything new, but instead clears the stains away from the purity that is already there. Jigme Rinpoche explained that this related to the symbolism of being washed at the start of all empowerments. Having faith in own our buddha nature, in our own pure being, is one of the requisites to receiving an empowerment. It’s the way to open up.

Morning fog resumed after a few days of clear skies. With or without the fog, the reading transmissions were broadcast from speakers on the monastery rooftops starting at 6:40 am, filling our little valley with the voice of Lhunpo Rinpoche. The logic was that people outside the shrine room could still receive the transmission even if they were working on tormas or performing other jobs. There was also a speaker set up in the old monastery next door so that Westerners practicing there could hear the lung too. Lhunpo Rinpoche will teach tomorrow on the nine yanas, the progressive stages of understanding, practice, and realization laid out in the Nyingma tradition. He is about 32 years old, the youngest son of Namkha Drimed Rinpoche. Presently, he lives in Toronto, Canada with his wife Khandro Chime, who arrived in Orissa a few days ago.

He studied for nine years at His Holiness Penor Rinpoche’s monastic college at Namdroling Monastery in Mysore, India, and has already received the Rinchen Terdzö three times. Lhunpo Rinpoche was visibly joyful throughout the empowerments and often played with the lamas when he brought them this or that vase or icon. He had the look of someone who practiced a lot. This afternoon we received twelve abhishekas, a new record. They were part of the series of the fifty empowerments related to the Seven-line Supplication To Padmasambhava. The Sevenline Supplication is written below, but you will see it is missing a crucial piece of recurring punctuation called a ‘tertsek,’ a terma mark. A tertsek usually appears as a pair of stacked circles with a horizontal line between them and is used show the end of every line in a terma.

HUM !

In the Northwest of the land of Uddiyana, !

On a blooming lotus flower, !

You have attained supreme, wondrous siddhi. !

You are renowned as Padmakara, !

Surrounded by your retinue of many dakinis. !

We practice following your example. !

Please approach and grant your blessing. !

GURU PADMA SIDDHI HUM

Translated by the Nalanda Translation Committee.

The Seven-Line Supplication is among the most well known supplications in Tibetan Buddhism.

It was written by the dakinis to call Padmasambhava when 500 arrogant religious extremists who were skilled in black magic threatened the early Indian Buddhist university, Nalanda. In that era, religious feuds were settled on the debating ground with the loser and his or her followers obliged to switch to the winner’s philosophical position. However, the extremists at Nalanda were not above using sorcery to achieve their aims. Padmasambhava was renowned both for his learning and the magical force of his meditative attainment. The scholars of Nalanda supplicated him with this chant, and Padmasambhava came and saved the monastery.

Later, when Padmasambhava arrived in Tibet, he gave this chant to King Trisong Detsen and his subjects. The Seven-line Supplication is included in many termas, often at the start. We heard it sung by His Eminence dozens of times during the abhishekas over the last three weeks. The supplication was chanted so often because we were in the guru yoga section and many of the empowerments were for guru yogas to Padmasambhava. The chant was woven into the section of the guru yoga empowerments where the teacher calls the deity, in this case Padmasambhava, to come and bless the disciples. The other day an exasperated friend said something like, “What is it with this tradition? Everything is all about Padmasambhava!”

It was really true. Padmasambhava’s presence was overwhelming, unstoppable, and unavoidable. We sat in a building and shrine room modeled after Padmasambhava’s pure realm, Copper Colored Mountain. All 800 of us sang his mantras for twenty or thirty minutes every day during the final blessings at the end of the abhishekas. Everyone was reciting his mantra, which is like the condensed essence of his name and energy, 100,000 times during the Rinchen Terdzö. We received dozens of empowerments for termas devoted to solely to him. He really was—and is—everywhere we go.

In such situations one is forced to contemplate why this man, an Indian, is so revered by the Tibetans. They cry out to the Buddha, but they cry out to Padmasambhava a lot louder. I think this is because Padmasambhava really, really cherished the Tibetans, and in turn they took on and protected the Buddhist tantric teachings that were soon to vanish from India. Padmasambhava first made sure the dharma was secure in Tibet, and then he did everything possible to enable the dharma to survive as long as possible through the terma teachings. I confess that before coming to the Rinchen Terdzö I had not really understood that without Padmasambhava we would not now have the tantric teachings, the terma teachings, the Shambhala teachings, or the two Sakyongs. Once I understood this important fact, supplicating Padmasambhava became like watering the roots of a huge tree, nurturing a connection that made everything possible. I was asking that connection to grow inside me and nourish everyone in the midst of this chaotic and difficult life.

Namkha Drimed Rinpoche was indefatigable. It was amazing to watch the joy and energy that he exuded during the abhishekas. At the same time everyone worried because he was working so hard. Yesterday the Sakyong said that at one point they tried to get His Eminence to abbreviate the abhishekas; there are ways to cut corners here and there. His Eminence refused to even consider it. He wanted to bestow the Rinchen Terdzö the way he had received it from the Vidyadhara. Every time I tried to express this to someone today I felt like crying.

Today we received 25 empowerments, a new record. Here are the first 34 of the 50 abhishekas related to the Seven-line Supplication followed by an explanation of each set: • 3 abhishekas of the three kayas! • 4 abhishekas of the four kayas! • 5 abhishekas of the five wisdoms

6 abhishekas of the six realms!

7 abhishekas of the seven successive buddhas

9 abhishekas of the nine stages of the path (8 manifestations of the Padmasambhava and one more)

As mentioned earlier, the kayas are a way to classify different aspects of awakened mind. The unfindable essence of the mind is a kaya. The mind’s manifestations, whether a pure body made of light or a physical body of a realized being like a buddha, is also a kaya. These three kayas can be presented as four kayas by presenting the three together with their unity. The five wisdoms empowerments connect manifestations of Padmasambhava to the five wisdoms, which are related to the transformation of our five basic emotional energies (passion, aggression, delusion, pride, and jealousy) into their inherent purity.

The famous teaching diagram, the Wheel of Life, traditionally painted at the entrance to a Tibetan monastery, depicts our experiences as a cycle through six realms or manifestations of samsaric, unenlightened being. These realms are both outer realms that we share with others and inner realms that we go through on our own. However, heaven and hell primarily depend on us. In the end, they are not something outside of our own mind. Each of the six realms contains a buddha and a corresponding manifestation of a Padmasambhava, which represent opportunities to wake up in the midst of all our various sufferings. One good thing to know about Padmasambhava is how he relates to Shakyamuni, the buddha of our era.

In the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, the Buddha stated that eight years after his passing from this world an enlightened teacher would come to teach the highest teachings and greatly benefit beings. The Buddha said Padmasambhava would be even more enlightened than he was, meaning that their realizations were equal, but that Padmasambhava’s expression of enlightenment would be extraordinary. The Buddha called Padmasambhava, ‘The Buddha Of Three Times’; the three times are the past, the present, and the future. Another key point in the tradition is that while the Buddha primarily taught the hinayana and mahayana, Padmasambhava primarily taught the vajrayana or tantric teachings. Today’s empowerments included a series of abhishekas for seven Padmasambhavas that related to the seven successive buddhas. These seven buddhas correspond with different periods of time in a Buddhism’s vast approach to history.

Chogyur Lingpa had a vision that a Padmasambhava would always accompany a Buddha in this world. The seven buddhas are the three buddhas of the three previous kalpas, the three prior buddhas of our own kalpa, and Shakyamuni who is the buddha of our era during the kalpa. A kalpa is a huge stretch of time, the period it takes for a universe to come into being, abide, depart, and have a gap before coming back again. His Eminence Tai Situ Rinpoche once explained that kalpa was like the life cycle of a planet. Shakyamuni is the 4th of the 1,000 buddhas who will appear in our kalpa. At the end of the day, we received nine abhishekas that related the nine yanas to the eight manifestations of Padmasambhava plus himself in the form of Yishin Norbu (The Wish- Fulfilling Jewel). The eight manifestations can be connected with eight phases in Padmasambhava’s life and are chronicled experientially in Trungpa Rinpoche’s book, Crazy Wisdom.

This evening Lhunpo Rinpoche gave his talk about the nine yanas. He spoke in Tibetan and was translated by the very knowledgeable Ripa sangha member from Minsk, Nickolai Almerov. Lhunpo Rinpoche taught with a soft and gentle voice beneath which lay a palpable eagerness to transmit the dharma. It was a treat to hear him starting to teach Westerners. He was peaceful, backed by the power of a quickly rising sun. The short talk covered the basic framework of the nine yanas and ended with him answering questions mostly about the vajrayana vows and samayas, the commitments connected with receiving empowerments.

What follows is a short study of food at the Rinchen Terdzö. I chose a secular topic because of the holidays. It is hard to make any definitive cultural statements about cooking in relation to the Rinchen Terdzö because of the effect of world cuisine upon the modern Tibetan kitchen. However, it is possible that two foods have remained constant staples at the Rinchen Terdzö since the nineteenth century: momos, or Tibetan dumplings, and salted butter tea. These two menu items are unavoidable in the Tibetan world. A food that has definitely been a part of the Rinchen Terdzö since its inception is tsampa, ground roasted barley flour. Tsampa is usually mixed with butter and sugar to make a torma, which is then consecrated, and sometimes eaten, during an empowerment. Torma dough can be rolled into little balls of medicine that are distributed as part of long-life ceremonies such as those in the Rinchen Terdzö. Other foods appearing in the shrine room included the yellow tea rolls that looked like unsplit hamburger buns, and, during the feast at the end of the day, cookies, candies, and blessed liquor that was mixed with a lot of orange soda.

The liquor was arak, something like barley vodka, but in Orissa it was often made from corn. Outside the shrine room, culinary possibilities opened up a bit. The Canteen, as the store was called, was run by a cheerful and energetic Tibetan man named Thonga and his family. The Canteen sometimes sold take-out vegetarian momos and ‘eggrolls’, a thin bread wrapped around a fried egg and some vegetables which were lathered in a special sauce—quite tasty and filling. The Canteen menu was usually made up of Indian fare, rice, dhal, and so on, along with a dense, homemade bread. Thonga also sold candy, pens, paper, and soda to a steady stream of monks along with the lay Tibetans and Westerners at the event. Occasionally we spotted Tibetan or Western children wandering around the monastery with neon pink cotton candy (which came is small plastic packages). Chicken momos and beer were available off the monastery grounds at a small restaurant at the edge of camp four. At the guesthouse, the kitchen usually prepared Indian food, noodle dishes, and a lot of fresh vegetables, along with the occasional momo meal.

His Eminence said that the Westerners should eat a lot of fresh vegetables so they were prominent on our menu. All of our vegetables were grown organically at the Tibetan settlement, with the exception of broccoli, which was sometimes brought from Berampur. We ate a lot of okra, chapattis, and we also sampled the occasional ting-mo (steamed bread dumpling) along with many styles of dhal with white rice. One vegetable I’d never tasted before was the deep green kati, which when sliced in halfmoons looks like the back of a stegosaurus. Kati means ‘bitter’, which it certainly was. It was easiest to eat when it was fried with something that turned it bright red. We heard from many people that kati was a remedy for hepatitis.

Today we nearly finished remaining abhishekas for Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye’s termas related to the Seven-Line Supplication. The abhishekas at the end of the day didn’t fit into the neat categories we had in the preceding days, however they emphasized connections between Padmasambhava and specific groups of gurus (48, 50, or 108) or between Padmasambhava and specific manifestations of enlightened activity. We also received empowerments for four wrathful manifestations of Padmasambhava. The evening teachings with Lhunpo Rinpoche covered the eight freedoms and ten favorable circumstances or conditions. The freedoms and favorable conditions point out the good fortune of being able to study and practice the dharma. They do this by highlighting the outer and inner conditions will support or cut off our path to enlightenment. Without a teacher who has followed the path of practice and realization, for example, we would be unable to genuinely enter the path ourselves.

At tea today, Alan Goldstein and his wife Semo5 Palmo made an elaborate offering to the Buddha, Padmasambhava, Avalokiteshvara, His Eminence, the Sakyong, and everyone attending the Rinchen Terdzö. As I mentioned earlier, the cycle of generosity is a regular feature of life in the Tibetan community. During the Rinchen Terdzö, people generally gave 5 Semo is the honorific word for daughter in Tibetan. Semo Palmo is one of the four daughters of His Eminence Namkha Drimed Rinpoche. money only to the monastics, but once in a while the donor gave a nominal amount (maybe 30 rupees, enough to buy an egg roll and a little candy at the store, less than 75 cents in the West) to the lay people, including the Western students. This was always an interesting moment. It provoked me to engage my ideas about generosity, the sangha at large, monasticism, and having wealth.

Some Westerners immediately wanted to give the money back, while others were happy to make an offering later and used their gift to buy something later on. Several years ago I was on pilgrimage in Bodhgaya, practicing each day under the Bodhi Tree (the place of the Buddha’s enlightenment) a few days before His Holiness Karmapa Urgyen Trinley Dorje’s first visit there. There was a steady stream of practitioners from all schools of Buddhism along with scores of tourists and Hindu pilgrims rolling through every day. Late one morning, a large, impoverished Indian family came to pay homage at this sacred place. It was clear they were Hindus because they devoutly walked counter-clockwise around the Bodhi tree.

At the back of the group was an older woman wearing a worn and faded yellow shawl. I imagined she was a grandmother in the family. She saw me, gently placed a rupee in my lap, and prostrated before me. I had two, nearly simultaneous reactions. One was fear because I had the thought there was no way I could really help this person who would be in and out of my life in an instant. The other reaction was totally non-verbal. The core of my heart involuntarily burst open with love. It was as though this moment itself was the real gift to me and I have pondered it many times since then. In Asia it is common for practitioners to be supported by communal generosity.

Many of the times that I have meditated for more than one session at a holy place in Asia, people I didn’t know have given me gifts. Sometimes I’d open my eyes at then end of a visualization, and I’d find that some fruit had been placed in front of me. At one site near Dharamsala, people learned I enjoyed bananas, so I was given a bag of them every day when I arrived at the temple gate. A seasoned traveler once said to me that Asians understand karma far better than we do in the West. They know that even a small gift or connection will nurture a link that can grow later on. In Tibet it is common to see pilgrims making aspirations and putting tiny amounts of money in front of every shrine they can at monasteries and pilgrimage places.

It’s a wonderful thing to make offerings to people and situations you may never meet again because it helps both parties make connections to kindness and goodness happening in the world. The electricity was out for most of the morning, which made it impossible for the monastery to publish their list of the afternoon’s abhishekas. Consequently, one of the chöpöns asked for our list. A few days ago, after working through the confusion of the 50 extra empowerments, Patricia started producing a polished Tibetan-English abhisheka list every day for the Sakyong and the Westerners here. She based her work on the empowerment list from His Holiness Penor Rinpoche’s most recent Rinchen Terdzö and on Peter Robert’s list of the empowerments given during His Eminence Tai Situ Rinpoche’s Rinchen Terdzö in 2006. As she had been doing earlier on, she revised her work by hand based on the monastery’s Tibetan language list before she sent a hand-edited draft of the empowerment list to the Sakyong and circulated her work among the Western students.

We received the last of the inner peaceful practices of the three kayas today. The two concluding empowerments were an abhisheka combing the fifty empowerments for the Seven-Line Supplication into one, and an abhisheka of Vajrayogini as the guru. Then we moved to a section of empowerments for auxiliary practices related to this section of abhishekas. These included empowerments for practices that focused on teachers in various traditions, connecting each of them with Padmasambhava, and included practices of the second Karmapa, Virupa, Padampa Sangye, Maitriyogin, and Dombipa.

These five came from a terma cycle discovered by Rigdzin Mingyur Dorje, who was born at the end 16th century and passed away in 1607 at the age of 23. Yet in that short time he revealed 13 volumes of termas. Hundreds of his discoveries were sky termas, objects and teachings found in space. A great many of his discoveries are included in the Rinchen Terdzö. He was so amazing that his teacher, Karma Chagme, wrote a biography of him. This evening we had a detailed talk on karma, the cause-result relationship in all actions, from Tulku Kunchab Rinpoche, one of the five main recipients of the Rinchen Terdzö. Tulku Kunchab Rinpoche is a nephew of His Eminence and in his third year at the Mindroling Shedra in North India.

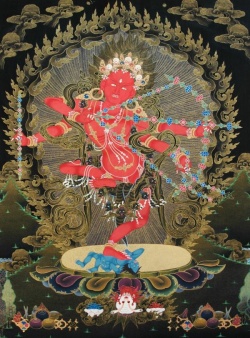

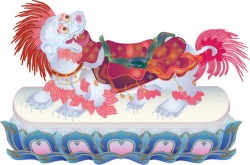

The abhishekas for the secret guru yoga practices, the wrathful manifestations of the guru, began this afternoon. Secret means not ordinarily noticeable, and wrathful refers to how enlightened compassion can manifest sharply if we disregard the peaceful messages of wakefulness. When Padmasambhava came to Nalanda to stop the black magicians who threatened the university, he manifested in a form of wrathful compassion called The Lion’s Roar, Senge Dradrok. In this form, Padmasambhava is red, fiery, and holding a vajra and an iron scorpion. The heart of a manifestation like this is love and realization, but outwardly it is terrifying.

One of the terma practices bestowed today was for Guru Drakpo Tsal, another very wrathful form of Padmasambhava. This particular Guru Trakpo Tsal abhisheka was part of a terma cycle of guru yoga practices revealed by Rigdzin Gökyi Demtruchen. This tertön’s name means something like ‘The one with the plume of vulture feathers.’ Rigdzin means ‘holder of awareness’, or vidyadhara in Sanskrit, and denotes the complete realization of dzogchen. Rigdzin Gökyi Demtruchen was born in 1337 and lived to the age of 71. He gained his name because he had what looked like three vulture feathers growing out of the top of his head when he was 12 years old. Two more grew when he was in his mid-twenties. This was amazing to everyone and marked him as a particularly special tertön because Padmasambhava’s crown has vulture feathers on its peak. Rigdzin Gökyi Demtruchen is part of a group of tertöns called The Three Supreme Emanations, three tertöns who were emanations of the body, speech, and mind of Padmasambhava.

Rigdzin Demtruchen (as he is sometimes known) was the emanation or embodiment of Padmasambhava’s mind. Guru Chökyi Wangchuk was the tertön who was an emanation of Padmasambhava’s speech, and Nyangral Nyima Öser was the emanation of Padmasambhava’s body, the aspect of his enlightened form. Short biographies of these last two tertöns appear later in this book. Rigdzin Demtruchen discovered a large terma collection that is now known as the Northern Termas because it was discovered in northern Tibet.

The earliest termas were found in the south, where Buddhism first took root in the land of snows. Dudjom Rinpoche, in his History Of The Nyingma Lineage explains that the Northern Termas are like a minister who beneficially serves all of Tibet and Kham because the Northern Termas contain a complete range of practices and teachings for taking care of a kingdom.

These include everything from the most profound instructions on mind and meditation, to rituals for increasing the spread of the teachings, ending epidemics, pacifying civil wars, and so on. The Northern Terma were said to be among the main practices of King Trisong Detsen. Interestingly, Rigdzin Demtruchen was the rebirth of Dorje Dudjom of Nanam, who was one of the ministers King Trisong Detsen sent to request Padmasambhava to come to Tibet. The Northern Termas also pointed out hidden sacred places in Tibet, places where dharma practice can be particularly strong. Later in his life, Rigdzin Demtruchen’s activity opened up sacred sites in Sikkim as well. Rigdzin Demtruchen’s termas and teachings are extremely famous and highly praised. He wrote a three-volume set of texts on dzogchen called the Gongpa Zangthal, Unimpeded Realization that is one of the three most detailed and meaningful presentations of dzogchen teachings. The other two presentations of dzogchen that have the same stature as the Gongpa Zangthal are the Longchen Nyingtig and the Nyingtig Yabshi.

The Gongpa Zangthal contains the famous dzogchen text, The Samantabhadra Aspiration. The reading transmissions from Rigdzin Demtruchen’s sons, consort, and disciples have all continued to the present day. Many of the practitioners in his lineage have achieved the rainbow body; a sign of which can be that a person leaves no physical remains behind at death. Last night, the Sakyong gave a lively, engaging, and practical talk to the Western sangha. He started it by telling everyone how he came to request the Rinchen Terdzö from His Eminence, the history of the Rinchen Terdzö with the Vidyadhara, and how things were going in Orissa so far. After that he went on to give us a sense of how to be in this situation, three months of teachings in a challenging environment. From there he went on to discuss the relationship between view and practice in the context of the Rinchen Terdzö.

There was a poignant moment in the middle of the talk when the Sakyong said that what he admired most about the Vidyadhara was his courage. He said that the older generation of Tibetans (he gave His Eminence as an example) has incredible strength and bravery. He encouraged us to develop those qualities in ourselves. At one point the Sakyong was asked a question about communicating through symbolism, which is a big part of the Rinchen Terdzö and vajrayana practice altogether. As he answered that it was possible to communicate with symbolism, the electricity abruptly cut out and left us in pitch darkness.

The coincidence filled the room with laughter. We listened as the Sakyong continued his talk in the dark without amplification. While he explained that the various manifestations of the deities and other symbols were meant to communicate our primordial nature, the lights abruptly sprung back on and an animal outside let out a bizarre yelp. This again filled the room with laughter.