Sāṃkhya

Note: The Sāṃkhya school was in its prime during the heyday of Yogācāra. The two schools were active rivals. In fact, the Sāṃkhyans were the Yogācārins' major non-Buddhist rivals. While eventually the Nyāya (Hindu Logic) and Mīmāṃsā (Hindu Ritualist Fundamentalist) schools mounted major criticisms of Yogācāra positions - particularly as developed in the Dignāga-Dharmakīrti strain of Yogācārā - the most telling debates until at least the late 7th century were between Buddhists and Sāṃkhyas (Vasubandhu devotes considerable attention to Sāṃkhyans already in his Abhidharmakośa-bhāṣya). Yogācāra borrowed some of its most important terminology from the Sāṃkhyans (e.g., pariṅāma, pravṛtti, etc.), and, while attempting to attach different nuances and connotations to those terms than were attributed to them by Sāṃkhya, traditional and modern interpreters of Yogācāra often read these terms through Sāṃkhyan prisms (influenced, no doubt, by the Sāṃkhyan use of such terms in well known Hindu texts such as the Yoga Sutras). When Xuanzang (600-664) was in India, one of his most memorable debates was with a Sāṃkhyan. Due to their terminological (and at times conceptual) proximity, it may be fair to say that early Yogācārins displayed some 'anxiety of influence' and took great pains to distance themselves from (what they considered) the more problematic Sāṃkhyan ideas, such as a permanent prakṛti (nature). Sāṃkhya, therefore, provides important context for understanding Yogācāra. For these reasons, we have included this survey of Sāṃkhyan thought on the Yogācāra Buddhism Research Association website.

Considered one of the oldest classical Hindu schools by Indian tradition, Sāṃkhya is most famous in Indian philosophy for its atheism, its dualist model of puruṣa (passive, individual consciousness) and prakṛti (nonconscious, cognitive-sentient body), and its theory that effects pre-exist in their cause. In its classical formulation the puruṣa/prakṛti model is analysed into twenty-five components (tattva) that are intended to encompass the entire metaphysical, cognitive, psychological, ethical and physical world in terms of their embodiment as individuals and the creative and interpretive projection of that world as experience by and for individuals. Both the world and the individual, in other words, are considered a phenomenological refraction and projection of the underlying and constitutive components of the conscious body. Falsely identifying with the cognitive and sensory components of prakṛti ( which according to orthodox Sāṃkhya performs cognitive and sentient operations but is bereft of consciousness; puruṣa alone is conscious), one believes oneself to be the agent of one's actions, rather than recognizing that actions are processes lacking any selfhood. Sāṃkhyans claim that liberation from the suffering of repeated rebirths can only be achieved through a profound understanding of the distinction between puruṣa and prakṛti. The latter is not abandoned after liberation, but continues to operate, observed with detachment by puruṣa, though, according to some versions, prakṛti eventually becomes dormant. Puruṣa and prakṛti are both considered beginningless and eternal. Since liberation is achieved through knowledge, Sāṃkhya stresses the importance and efficacy of knowledge over ritual and other religious endeavors.

Sāṃkhya is cognate to the word saṃkhyā, meaning 'to count' or 'enumerate.' Thus Sāṃkhya seeks to enumerate the basic facts of reality so that people will understand them and find liberation. Basic Sāṃkhyan models and terms appear in some Upaniṣads and underlie important portions of the epic Mahābhārata, especially the Bhagavad Gītā and Mokṣadharma. No distinct Sāṃkhyan text prior to Īśvarakṛṣṇa's Sāṃkhya-kārikās (ca.350-450) is extant. It enumerates and explains the twenty-five components and a subsidiary list of sixty topics (ṣaṣtitantra) which are then subdivided into further enumerative lists. Most of the subsequent Sāṃkhyan literature consists of commentaries and expositions of the Sāṃkhya-kārikā and its ideas, which continued to be refined without major alterations well into the 18th century. Sāṃkhyan models strongly influenced numerous other Indian schools, including Yoga, Vedānta, Kashmir Shaivism and Buddhism.

1 Historical Overview

Sāṃkhya claims origins in remote antiquity, identifying its founding preceptors with names found in the Vedas - the earliest Indian texts (ca.2000-800 BCE) - such as Kapila, Āsuri, etc., but nothing in the early material points to these people as having particularly Sāṃkhyan views. Some Sāṃkhya texts assert that its teachings predate the Vedas. Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra (ca.300 BCE) mentions Sāṃkhya as one of the leading teachings of the day. The epic Mahābhārata, variously dated between 400 BCE-200 CE, contains sections revealing a sophisticated, elaborate Sāṃkhyan system. In one section, the Mokṣadharma, the basic system of twenty-five components is already found, along with a twenty-six component system, adding a universal single puruṣa as the twenty-sixth. This universal, cosmic puruṣa, or 'ultimate self', was retained in the Yoga school, which in many other respects developed parallel to Sāṃkhya. The Mahābhārata's most famous section, the Bhagavad Gītā, not only presents a detailed discussion of early Sāṃkhya theories, but structures its characters and plot to reflect those models. Both sections, emphasizing the indispensability of knowledge, use the terms 'field' and 'knower of the field' as synonyms for prakṛti and puruṣa, respectively. The Buddhist poet Aśvaghoṣa, in his Practices of the Buddha (Buddhacaritam) (1st-2nd century), treats Sāṃkhya thought as one of the formative teachings studied by the Buddha on his way to enlightenment, suggesting that by Aśvaghoṣa's time there already existed a developed Sāṃkhyan tradition considered ancient and influential even by its opponents.

Orthodox Sāṃkhya begins with the appearance of Īśvarakṛṣṇa's Sāṃkhya-kārikās which synthesized centuries of conflicting Sāṃkhyan speculation. Its roughly seventy verses (the number varies in different commentaries) concisely presents the models, terminology, arguments, and systematic configurations that were to be definitive for Sāṃkhya from that time on. Virtually every subsequent Sāṃkhya text is either a commentary on the Sāṃkhya-kārikās or a commentary on the Sāṃkhya-sūtra, a text that appears around the fifteenth century which itself may be considered an expanded, reorganized version of the Sāṃkhya-kārikās. The many dozens of commentaries written over the centuries reflect the changing concerns and growing sophistication of Indian thought in general. While some of the commentaries display clever strategies and great erudition, and minor points are continually being redefined and reinterpreted, the basic parameters set by Īśvarakṛṣṇa are scrupulously followed. The same stock arguments and examples invariably appear century after century in every commentary - sometimes with embellishments - but no truly creative innovations to the system itself emerge. The earlier commentaries endeavor to deploy the latest developments in Indian epistemology and argumentative discourse to defend the statements of the Sāṃkhya-kārikās from actual and possible objections; the later commentaries make increasing concessions to non-Sāṃkhyan ideologies, often to the point of subverting or reversing the point of distinctive Sāṃkhyan teachings while attempting to retain the terminology and basic structure established by Īśvarakṛṣṇa. While orthodox Sāṃkhya, for instance, claimed that each individual possessed its own distinct puruṣa, later commentators sought to ground this multiplicity of selves in a universal single Self; orthodox Sāṃkhya denied the existence of God, but some later commentators reinserted God back into the system or encouraged their readers to reject Sāṃkhya's atheistic claims. These later concessions, whose most important advocates were Vācaspati Miśra (9th-10th century), Aniruddha (15th century) and Vijñānabhikṣu (16th century), were not so much efforts to change or reform the Sāṃkhya system as they were attempts to make Sāṃkhya palatable to contemporary audiences or promote reforms in the non-Sāṃkhyan ideologies of the day to which these commentators owed their true allegiance. They may have been emboldened by the Yoga School (whose classical text is Patañjali's Yoga Sūtras), which, unlike Sāṃkhya, accepted the existence of God (identifying God with puruṣa). Yoga also rejected the Sāṃkhyan duality of puruṣa and prakṛti, claiming instead that ultimately the latter dissolves into the former.

2 Puruṣa and prakṛti

The term puruṣa originally meant 'person,' and is used in the Ṛg Veda to signify the primordial, cosmic Person from whom the universe is created (10.90, Puruṣa Sūkta). Ṛg Veda I.24.7 says, 'Two birds ... inseparable companions, have found refuge in the same sheltering tree. One incessantly eats from the peepal tree; the other, not eating, just looks on.' This image of an inseparable dyad, one part actively engaging its appetites and appropriational desires, and the other passively observing the activity of the first part, prefigures the notion of puruṣa and prakṛti.

In Sāṃkhya puruṣa signifies the observer, the 'witness'. Prakṛti includes all the cognitive, moral, psychological, emotional, sensorial and physical aspects of reality. It is often mistranslated as 'matter' or 'nature' - in non-Sāṃkhyan usage it does mean 'essential nature' - but that distracts from the heavy Sāṃkhyan stress on prakṛti's cognitive, mental, psychological and sensorial activities. Moreover, subtle and gross matter are its most derivative byproducts, not its core. Only prakṛti acts. Puruṣa and prakṛti are radically different from each other, though both are considered beginningless, eternal, and ultimately inseparable. Every person is constituted of conjoined puruṣa-prakṛti. Misunderstanding how these two function and interrelate is the root cause of all problems. Liberation arises from properly distinguishing between them - such that one ceases to falsely identify with the components of prakṛti as one's self and instead correctly understands that puruṣa is a dissociated watcher of the activities of one's prakṛti.

Primordially prakṛti is composed of three primary 'strands' or 'qualities' (guṇa):

sattva which is light, clear, tranquil, joyous, kind, etc.,

rajas which is passionate, moving, dynamic, agitated, angry, etc., and

tamas which is dull, inert, dark, depressed, stupid, etc.

Everything in the universe (except puruṣa) is composed of varying proportions of these three qualities. Physical objects, mental and emotional states, moral qualities, types of food, personality types, etc., are all definable according to which quality predominates. Rajas and tamas signify the inertia of motion and rest, respectively. Sattva signifies the clarity and tranquillity that comes from 'rising above' the negative properties of the other two qualities. For instance, by shaking up or moving (rajas) something sedimented, depressed, stuck (tamas), it may either return to tamas (resediment), or remain dynamic (rajas), or it may purify and become sattvic. A clear and peaceful condition, if disturbed by passion or violent activity, can transform into reciprocal anger and violence, or produce stupidity, depression and stubbornness. Such dynamics can be applied to psychology, politics, physics, soteriology, or any other field. The three qualities undergo perpetual transformation, those transformations being the empirical universe. The essence of the three qualities remains unmanifest, acting as the cause of the empirical world (manifest prakṛti) which, as effect, shares the same nature as its cause. Sāṃkhya-kārikā characterizes their function thus: sattva is 'illuminating', rajas is activating or unfolding, and tamas imposes limitations and restrictions. They are inseparable, like the wick, oil and flame of a lamp (tamas, rajas and sattva, respectively). Sattva and tamas are comparable to the Chinese principles of yang and yin, respectively, with rajas acting as the catalyst and dynamic agent that keeps the other two active.

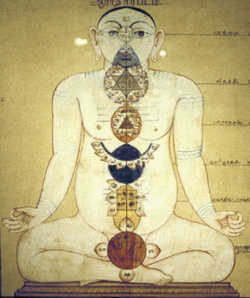

Orthodox Sāṃkhya analyses puruṣa-prakṛti into twenty-five fundamental components. One is puruṣa; the remaining twenty-four are aspects of prakṛti, each a further development or transformation of the three qualities. These twenty-five components account for the totality of the universe as well as the components of each individual:

2. The three qualities, also called 'fundamental prakṛti' and the 'unmanifest'. The remaining components, lumped together as the 'manifest', are all formed from combinations of these three.

3. Buddhi, reflective discernment and discrimination. Puruṣa is most directly connected to buddhi, through which it is aware of the activities of prakṛti. It is buddhi's task to effectively distinguish between puruṣa and prakṛti.

4. Ahaṃkāra, literally 'I-maker' or 'the constructor of the "I am".' The 'I'-maker refracts the three qualities to generate the sensorium which it then appropriates for itself, thus constructing a sense of subjective selfhood. That is, it interprets the activities of the three qualities in such a way that it sees itself as the agent or origin of the experience (or theory) and experiences the results as 'my experience'. The intensity of its sense of self-concern disrupts and obscures buddhi's understanding of its relation with puruṣa.

5. The empirical mind (manas) interprets the sensorium, coordinating the discrete sense fields (audition, vision, etc.) into coherent experience.

6-10. The five sense capacities, viz. hearing, touching, seeing, tasting and smelling.

11-15, the five activity capacities, viz. speaking, grasping, mobility, excreting and procreating.

16-20. the five subtle elements, viz. sound, tactility, color/form, taste and smell.

21-25. the five gross elements, viz. ether, air, fire, water and earth.

3 Developing Formulations

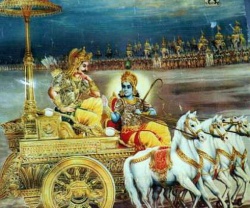

The Bhagavad-Gītā recounts the conversation between the warrior Arjuna and his charioteer Kṛṣṇa on a battlefield where the two sides of Arjuna's family are fighting for the throne. Arjuna represents prakṛti while Kṛṣṇa represents puruṣa. Bound together in one body (the chariot) they engage the battle of life and death on the 'field of Dharma' (the cultural context of human action). On a hill overlooking the battle in another chariot are the blind king Dhṛtarāṣṭra (for whose abdicated throne the battle is being fought) and his charioteer Saṃjaya. Saṃjaya relays to the king what Arjuna and Kṛṣṇa are saying on the battlefield (the Gītā is largely Saṃjaya's narration), despite the clamorous noise on the battlefield and the fact that the king is not deaf. Each chariot represents a puruṣa/prakṛti complex, emphasizing that each conscious body is perpetually engaged in interpreting its cognitive-field. Out of the rajasic tumult of the battle, Arjuna falls into a tamasic, paralyzed state that Kṛṣṇa cures by sattvically leading Arjuna to an understanding of the conditions he embodies. By learning from Kṛṣṇa, Arjuna is learning from his own self. By understanding how puruṣa is embodied in prakṛti, knowledge frees him from his paralysis, allowing him to engage in correct and necessary action. Arjuna becomes the 'knower of the field.'

The Gītā offers early, formative versions of Sāṃkhyan models. It defines 'lower prakṛti' as 'eightfold' ('higher prakṛti' is the three qualities): 'earth, water, fire, air, ether, mind, buddhi, and the "I"-maker' (VII.4-5). This list omits the ten capacities and five subtle elements. However at XIII.5-6 another list, this time exceeding the standard twenty-four items of prakṛti, is given:

5. The (five) gross elements, the "I"-maker, buddhi, the unmanifest, the ten capacities, and one (mind) and the five sensory realms;

6. Desire and aversion, pleasure and pain, the bodily aggregate, awareness, will; ...'

(tr. by Antonio de Nicolas, modified).

This list mentions 'five sensory realms' instead of the five subtle elements. The idea of subtle elements and their accompanying notion, the subtle body (see below), apparently developed later. Notice that pleasure and pain are included here in prakṛti. Yet in the same chapter the Gītā says (XIII.20), 'Prakṛti is said to be cause of the generation of causes and agents; puruṣa is said to be cause in the experience of pleasure and pain.' Clearly pleasure and pain are being posited to both puruṣa and prakṛti, jeopardizing their radical distinctness. While here puruṣa is said to be the cause of pleasure and pain, orthodox Sāṃkhya will insist that puruṣa neither causes nor is caused. Moreover prakṛti is described as 'awareness,' a property that orthodox Sāṃkhya will insist is found only in puruṣa.

Later Sāṃkhya texts offer divergent opinions on how unmanifest prakṛti generates the remaining components. For instance, for some the order of transformation seems to follow the numerical sequence. Others, perhaps thinking that gross elements or at least subtle elements would be required for there to be the five sense capacities and five activity capacities, held the subtle and/or gross elements to be prior. Others, perhaps more idealistically, asserted that it is the intent to hear that produces the physical ear, not the other way around, so that the capacities produced the elements, effectively treating the elements as constructions or projections of the sense and activity capacities. There are also differing opinions on whether it is buddhi, the 'I'-maker, mind, or some combination between them that produces the rest of lower prakṛti, and even which part of lower prakṛti each might produce. Sāṃkhya-kārikā claims that the 'I'-maker is pivotal: with sattva it produces the ten sense and activity capacities, with tamas it produces the subtle and gross elements.

While orthodox Sāṃkhya always considers puruṣa a single entity (though there are a multiplicity of puruṣas since each individual has its own), the Gītā posits three puruṣas per individual: a perishable puruṣa, an imperishable puruṣa, and a highest puruṣa also called ultimate self.

4 Buddhi

Buddhi alone among the twenty-four components of prakṛti directly interacts with puruṣa. Orthodox Sāṃkhya wishes to maintain (1) a radical distinction between puruṣa and prakṛti, and (2) a prakṛti that is at once fully cognitive, sensorially aware and active, intellective, etc., and at the same time non-conscious (acetana). How can buddhi be rational, discerning, reflective, discriminative, in short, cognitive, and yet lack consciousness? Buddhi must provide both the linkage or communication between puruṣa and prakṛti, as well as generate the discernment that realizes their ultimate separation. Since Sāṃkhyan soteriology relies on buddhi to discern that separation, and the relation between the radically incommensurate puruṣa and prakṛti resides in the function of buddhi, the coherence of the entire system rests on the coherence of the notion of buddhi.

Prakṛti is not 'insentient', since the senses and their functions operate entirely within prakṛti. The five sense capacities are said to possess 'bare awareness' of their objects. The empirical mind is described as both a sense organ and a conceptualizer. The 'I'-maker generates the sense of subjectivity. Buddhi discriminates, decides, reflects, and provides certainty.

Reserving conscious knowing exclusively for puruṣa, while assigning all cognitive, psychological and sensory activities to prakṛti only seems confusing, argues Sāṃkhya-kārikā, because we mistakenly transfer the properties of one to the other due to their proximity: prakṛti seems to be conscious and puruṣa seems to be active, but in fact they are not. Iron becomes hot when in proximity with heat, but heat is not in its nature, they argue. Puruṣa and prakṛti support each other and are compared to the symbiosis of a blind man and a lame man. In order to travel the blind man (i.e., prakṛti), who can't see where he is going, can carry the lame man (i.e., puruṣa), who can't walk but can see and direct the blind man. But since directing a blind man may be construed as an activity and the blind man must be sentient to cooperate with and be useful to the lame man, this example confuses rather than clarifies the problem.

5 Orthodox epistemology

Sāṃkhya-kārikā, like Buddhism and many other Indian schools, claims that the root problem as experienced is a profound sense of dis-ease and dissatisfaction (duḥkha) that can only be cured by knowledge. Some commentaries say this 'knowledge' concerns the difference between puruṣa and buddhi; some say it is knowing the twenty-five components and/or the list of sixty topics. Sacrifice, ritual and scriptural remedies - the usual methods for an orthodox Hindu - are declared ineffective for anything except temporary rebirth in a heaven; moreover those methods cannot guarantee success (e.g., even authentic prayer and religious observance may not cure barrenness), and often involve 'impurity' (the killing during sacrifice, the caste requirements to have intercourse with one's mate, etc.). Heavenly births and impurities both perpetuate the cycle of life and death rather than resolving it. Like Buddhists, Sāṃkhyans consider existence in any realm into which one is reborn, whether the human realm or another, including the heavens, to be transitory.

Sāṃkhya accepts three valid means of knowledge (pramāṇa): perception, inference and reliable testimony. Descriptions of all three vary from commentary to commentary. Among Īśvarakṛṣṇa's predecessors, Vārṣagaṇya (ca.100-300) reportedly defined perception as the function of sense organs; Vindhyavāsin (ca.300-400) added that 'valid' perception was devoid of mental or linguistic construction; and Īśvarakṛṣṇa added that it ascertains specific and definite objects. Interestingly, Buddhism later mirrors this progression, going from the early Abhidharma definitions of perception in terms of sensory functions, to Dignāga's stipulation that it be without mental construction, to Dharmakīrti and Dharmottara's claim that perception attains specific, definite objects. The Yuktidīpikā, one of the fullest and most sophisticated of the commentaries on Sāṃkhya-kārikā, further asserts that the instrumentality of perception (i.e., the pramāṇa) is located in buddhi, but its results occur in puruṣa.

The discussions of inference also vary across the commentaries, reflecting developments in Indian logic. Sāṃkhya-kārikā states somewhat cryptically that inference is threefold, based on a mark and its antecedent mark. The early commentators assumed 'threefold' referred to three types of inference discussed in the Nyāya Sūtra. The Sāṃkhya-vṛtti (author and date unknown) describes them thus:

inferring from what precedes, e.g., inferring imminent rain from storm clouds;

inferring the whole from a part, e.g., inferring all sea water is salty by tasting one drop; and

generalization, e.g., inferring that because one tree is in bloom others must be likewise.

The Suvarṇasaptati - a Sāṃkhya-kārikā commentary that only survives in a Chinese translation made by Paramārtha in the 6th century - states that inference is dependent on perception. It redefines the three types as follows:

'inferring from what precedes' means to infer an effect from the perception of a cause (e.g., rain from a black cloud);

the second means to infer a cause from the perception of an effect (e.g., inferring previous rain from a flood); but 3.

'generalization' is treated as above. Gauḍapāda (6th century), in his commentary Sāṃkhya-kārikā-bhāṣya, gives as an example for 'generalization' or 'general correlation', seeing that someone is first in one place and then another, one infers movement even though the movement itself was not perceived. 'Generalization' is also sometimes made equivalent to the notion of logical/ontological concomitance (vyāpti) advanced by the Nyāya school.

This last example is important since orthodox Sāṃkhya argues that merely because something is not perceived does not mean it does not exist, as when one knows the Himalayas have a top without actually seeing it. Imperceptibles may be proven to exist through inference. Since Sāṃkhyans are atheists it is not God they are trying to prove but rather puruṣa and unmanifest prakṛti. Sāṃkhya-kārikās 8 states that prakṛti is too subtle to perceive, but it is 'perceived through its effects'. Sāṃkhyan arguments for the knowability of imperceptibles by means of inference are disappointing, since they fail to distinguish between what is not perceived but in principle perceptible on the one hand, and what is genuinely imperceptible on the other. Their examples all address the former variety. Even when the Yuktidīpikā records this objection from a Buddhist, its response continues to ignore the distinction.

The most repeated 'proof' for the existence of puruṣa is a questionable argument from design (e.g., Sāṃkhya-kārikā 17): The body (i.e., prakṛti), like a bed, is composite in nature (implying it was put together), therefore it must be for something other than itself. The only existent other than prakṛti is puruṣa, therefore prakṛti and its operations must be for the benefit of puruṣa. The usual argument offered to prove that the imperceptible unmanifested three qualities are the cause of the manifest world is that an effect must be of the same nature as its cause, and the effects of the three qualities are observable everywhere in the manifest world since everything can be seen as varying proportions of the three qualities. This is illustrated by an analogy of cloth and thread. Thread, when woven, becomes cloth, though, in nature, there is no difference between thread and cloth. This example must have been particularly appealing to Sāṃkhyans since guṇa (quality) also means 'thread'. Since for the Sāṃkhyans the qualities function as material causes as well as efficient causes, they were satisfied with this argument, though the thread does not 'transform' in the manner posited of prakṛti. The Yuktidīpikā states that fundamental prakṛti, because it is too subtle, lacks the 'function of movement,' but instead has the 'function of transformation.' Transformation, it says, is when an object obtains new qualities without deviating from its essence, such as when a piece of black palāśa wood becomes yellow because of exposure to heat, and yet never stops being palāśa wood. However, the change from threads to cloth is certainly not a 'transformation' in this sense.

The Yuktidīpikā describes the ten factors that constitute a logical proof. These include five psychological 'conditions for an inference':

desire to know,

doubt,

purpose,

examining alternative possibilities,

removal of doubts;

and the five parts of an actual syllogism:

thesis,

reason,

example,

application, and

conclusion.

The Māthara-vṛtti, another Sāṃkhya-kārikā commentary, discusses the later Indian three part and five part syllogisms in a manner consistent with their explication in Nyāya and Buddhism.

As for testimony or reliable authority, like most Hindu schools Sāṃkhya accepts scripture and the testimony of a reliable person as valid means of knowledge. The Yuktidīpikā, for instance, asserts that the legendary ancient preceptors of Sāṃkhya, such as Pañcaśikha (mentioned in the Mahābhārata), actually perceived the effect in the cause, so that the Sāṃkhyan causal theory rests on their authority.

6 Causal theory

Sāṃkhya-kārikā advances the theory that the effect pre-exists in the cause (satkāryavāda) in a latent or potential state, arguing that since something cannot arise from nothing, the effect must pre-exist. It further claims that all effects rely on a material cause; things do not arise indiscriminately from just anything, i.e., certain types of causes produce certain types of effects (e.g., cows don't give birth to puppies); something can only produce what it is capable of producing, and a producer can only produce what is capable of being produced; the nature of the cause is in the effect. It says elsewhere that all manifest things must have a single ultimate cause, the reason being, according to the commentaries, to avoid an infinite regress of causes and effects. This ultimate cause is prakṛti.

Other causal notions are found in the various commentaries. Gauḍapāda's commentary states that each of the three qualities produces conditions conducive to the other two as well as to itself. 'Thus sattva, like a beautiful woman, is a joy to her husband, a trial to her cowives, and arouses passion in other men,' (i.e., sattva, tamas, rajas, respectively).

The Sāṃkhyasaptati-vṛtti discusses two types of causes: 1. productive causes, which entail fundamental prakṛti, buddhi, the 'I'-maker, and the subtle elements; and 2. cognitive causes, which includes five types of misconception , twenty-eight types of dysfunctions (of the sense- and activity-capacities, mind, and buddhi), nine contentments, eight types of attainment and the cognitive constructions of the eight predispositions.

There are also scattered discussions on material, efficient and instrumental causes, but these are merely adopted from other Indian schools. Sāṃkhya seemed more interested in specific causal sequences and correlations between its various enumerated lists than in an elaborate theory of causality in itself. The Yuktidīpikā criticizes Buddhist 'momentariness' and the causal theories of Vaiśeṣika and Nyāya, but the arguments shed little light on causal theory in general.

7 Soteriology

Sāṃkhya-kārikā states that the purpose for which the experiential world is created by the conjoining of puruṣa and prakṛti is so that the former can 'see' the latter, and the latter can liberate (lit. 'isolate') the former. Everything prakṛti does, she does for the liberation of puruṣa. 'Just as unaware milk operates as an efficient cause to nourish a calf, so does prakṛti operate as an efficient cause for the liberation of puruṣa' (Sāṃkhya-kārikā 57). Just as a dancer stops dancing once the audience has seen the performance, so does prakṛti stop after having illumined puruṣa. She, like a self-sacrificing mother, does everything for the sake of puruṣa, while puruṣa lends no assistance whatsoever.

The Sāṃkhya-kārikā-vṛtti declares that buddhi enlightens and attains liberation for puruṣa. Critics of Sāṃkhya have been quick to point out that puruṣa is defined in Sāṃkhya-kārikā 19 as inherently liberated and indifferent to pain and pleasure, thus it should be in no need of liberation. Sāṃkhya's response to this criticism again hinges on buddhi, but with an additional notion, the 'predispositions' (bhāva). The predispositions that bind and liberate are classified into three types and into eight types. The three are

innate,

natural and

acquired.

The eight are

Dharma (meritorious actions), which leads to rebirth in a higher life;

Adharma (demerit), which leads to lower births;

knowledge, which leads to liberation;

ignorance leading to bondage;

detachment leading to dissociation from the activities of prakṛti;

attachment producing the cycle of birth and death;

power conducive to controlling circumstances; and

impotence leading to loss of control. The positive four (1,3,5,7) are considered sattvic, their opposites are considered tamasic.

The Sāṃkhyasaptati-vṛtti defines the Innate predispositions as Dharma (here meaning meritorious actions), knowledge, detachment and power; the Natural predispositions are latencies that emerge at certain times in one's life; and the Acquired dispositions are derived from learning the truth from a teacher. Gauḍapāda defines the Innate as the eight predispositions constituting one's inherent nature; Nature is the eight dispositions resulting from previous lives; and the Acquired is the eight predispositions obtained by hearing the truth from a teacher. He adds that the predispositions reside in buddhi and shape the (gross) embryo. Of the eight, knowledge alone leads to liberation. To the extent that the other seven contribute to knowledge they are conducive to liberation, but only knowledge can effect release.

The predispositions and the subtle body cannot operate without each other. The subtle body is composed of the internal organs, the ten capacities and the five subtle elements. It does not experience anything, but is the repository that holds the predispositions. Impelled by these predispositions, the subtle body is reborn from life to life, until the predispositions are eliminated by knowledge. The subtle body is neither a 'self' nor invariant, since it is perpetually being modified by the predispositions influenced by the fluctuations of prakṛtic experience.

Puruṣa, prior to liberation, watches prakṛti's transformations and 'suffers' the pain of old age and death. But those transformations are merely an unconscious movement, a 'dance' designed to show puruṣa that in its own nature it is never bound or liberated. 'Then, standing aside like an spectator, puruṣa views prakṛti who, having fulfilled her purpose, stops, turning her back on the seven forms' (v 65), i.e., all the predispositions except knowledge. Though puruṣa and prakṛti are still conjoined, no new creation is generated, no new predispositions are created. By the attainment of correct knowledge, the seven predispositions cease to cause further embodiment, and yet, "like a potter's wheel that continues to spin even after the potter has stopped applying force," embodiment continues for a while.

Having fulfilled its purpose, prakṛti ceases functioning, sometimes understood to mean that the qualities return to an equilibrium from which no further 'transformations' emerge. Attaining separation from the body, puruṣa attains everlasting 'isolation' or 'freedom' (kaivalya).

References and further reading

Chakravarti, Pulinbehari. (1951) Origin and Development of the Sāṃkhya System of Thought, Calcutta: Metropolitan Printing and Publishing House Ltd. (A substantial treatment of the early sources.)

Chapple, Christopher. (1986) Karma and Creativity, Albany: State University of New York Press. (Deals with Sāṃkhyan models found in several texts, including the Mahābhārata and Yogavāsiṣṭha in an insightful and lucid manner.)

De Nicolas, Antonio. (1976) Avatāra: The Humanization of Philosophy Through the Bhagavad Gītā, NY: Nicolas Hays. (Penetrating, original interpretation of the Gītā that includes a superior English translation.)

Larson, Gerald. (1979) Classical Sāṃkhya, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. (Includes review of earlier scholarship, an analysis of Sāṃkhya-kārikā with romanized Sanskrit text and translation in an appendix.)

Larson, Gerald, and Ram Shankar Bhattacarya, eds. (1987) Sāṃkhya: A Dualist Tradition, Princeton: Princeton University Press. (A volume in the Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, this is the most comprehensive English work to date on the subject. Includes historical and philosophical overviews, summaries of every major text and thinker in the tradition, and a careful delineation of all the major and minor terms and lists.)

Mainkar, T. G., (translator) (1964) The Sāṃkhyakārikā of Īśvarakṛṣṇa with the Commentary of Gauḍapāda, Poona: Oriental Book Agency.

Johnston, E. H. (1937) Early Sāṃkhya, London: Royal Asiatic Society. (An important examination of the early Sāṃkhya tradition.)

Takakusu, M. (1904) 'La Sāṃkhyakārikā étudiée à la lumière de sa version chinoise (II)', Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême Orient, vol IV, Hanoi, 978-1064. (French translation of the commentary translated into Chinese by Paramārtha, Jin qi shi lun, Taisho#2137.)

Raja, C. Kunhan. (1963) The Sāṃkhya kārikā of Īśvarakṛṣṇa, Hoshiarpur, India: V.V. Research Institute. (Translation with romanized Sanskrit text, includes the translator's commentary drawn from Gauḍapāda and Vācaspati Miśra.)