Dream Yoga And The Practice Of Natural Light By Namkhai Norbu

Dream Yoga And The Practice Of Natural Light By Namkhai Norbu

Namkhai Norbu, 1938-

remember as many as eight dreams a night. On this particular night, I suddenly had the realization that I was both asleep and aware that I was dreaming. At the instant of the realization, the colors of the dreamscape became startlingly

vivid and intense. I found myself standing on a cliff and looking out over a vast and beautiful valley. I felt relaxed and thrilled, and I reminded myself it was only a dream.

I looked out over the lovely vista for a short time and then resolved to go a step further, literally and figuratively. If it was truly a dream then there would be no reason why I couldn’t fly. I leapt into space but, instead of flying, I found the dream transforming once again. Still

lucid, my awareness appeared to be on a stairway. My body was no longer in the dream but I was moving up the stairs. I had gone up one step and was making my way up another when the dream changed again. This time it was just black with no imagery whatsoever. I resisted the impulse to open my eyes. In truth, I was uncertain what to do, but I wished and willed the imagery to return and then suddenly I was back on the stairway. This recurrence of the stairway

imagery lasted only momentarily and then I awoke.

The whole experience had been fascinating. I still consider it one of the most meaningful experiences of my life. The lama who supervised the retreat likened my experience to having passed a driving test. Subsequently, I have had many lucid

experiences during dream. I can’t say that they occur each night, but they do occur regularly. Their frequency increases during times when I practice meditation intensively, such as when in retreat. Also, if I awaken and practice meditation during the night I find that I frequently have lucid dreams upon returning to sleep.

Over the course of time, I have also had dreams that were psychic in nature. For example, while on retreat, I dreamt of my lover. Although I was not lucid during the dream, my recollection was clear. Her image appeared. She was luminous, radiant, and yet she was sobbing. I had made plans to pick her up at a

train station in upstate New York the next day. To test my dream experience, I told her that I was very sorry she had been distraught the previous night. Her look of surprise told me instantly that the dream was accurate. She told me that she had been ill and had indeed cried bitterly.

As I mentioned, it seemed clear that these experiences increased when I had the opportunity to practice meditation or the dream yoga instructions intensively. It was during such a period that I joined Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche for a seminar in Washington, D.C. He had been traveling with one of his

oldest students and she had become seriously ill. In my dream, I found myself with Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche. He was very preoccupied with the student’s health crisis. I said, “Rinpoche, she’s dying.” Rinpoche replied, “No, I’ve treated her, and she’s getting better.” The next day the good news was that she

was indeed recovering, but even more startling was Norbu’s awareness of our dream conversation before I told him about it. Later I had other dreams where Norbu was talking with me, and occasionally I would also say something intelligent in return. Norbu would take great interest in these experiences, and

sometimes the next day would ask me if I had had an interesting dream the previous night. Occasionally he would ask me, and if I only vaguely remembered, he would say, “You must, you must try to remember.”

Not long ago I visited my parents’ house. They have lived there for my entire life. I slept in the same room where I slept as a child. As I slept, I had a dream that there was a snake in the bed with me. Rather than threatening me it seemed to want to cuddle like a pet. Although I was not completely lucid, I

recall wondering what to do with this friendly though clearly uninvited snake. Upon awakening, I thought about this dream and its meaning at some length. Perhaps I had become more comfortable with that which was once fearful. Then again, I remembered Norbu’s comment that with increased clarity, dreams might

come to be something like a United Nations conference. Might the dream snake have been a “delegate”? For it is Norbu’s contention that there are many classes of beings with whom it is possible to communicate within the dream state.

Countless theories have been developed to account for the universally shared set of experiences we call dreaming. Although these theories may differ radically regarding the origin and significance of dreams, there is widespread agreement that many dreams are mysterious, powerful, and creative. Dreams have held a central place in many societies. In many cultures the importance of dreaming was taken for granted, and the ability to remember or even

consciously alter a dream was nurtured. Dreams have figured prominently—sometimes centrally—in religions, assisted on the hunt, inspired sacred patterns for arts and crafts, and provided guidance in times of war, crisis, or illness. The dreamer of a “big dream” was frequently referred to as a priest or priestess, a title earned by virtue of their having been blessed by the gods.

Ancient Egyptians and other traditional peoples systematically interpreted dreams for the purpose of deciphering messages from the gods. Egyptian priests called “masters of the secret things” were considered intermediaries. With the advent of writing, the knowledge of dream interpretation was recorded. An

early book on dream interpretation, written in Egypt some two thousand years before the common era, is contained in what is now called the Chester Beatty papyrus. In many cultures, dreamers preparing to receive an important or healing dream participate in elaborate rituals. These rituals, widespread in

early history, are especially well documented in Native American societies as well as in Asia, and in ancient Babylon, Greece, and Rome. Invocational or “incubation” ceremonies would feature rituals guided by trained initiates, and frequently took place in special temples built on important and beautiful sacred sites.

After making offerings to the gods or a sacrifice for purification, the dream seeker would sometimes drink potions to enhance the experience. Depending on the culture, the ingredients for these potions might include a variety of psychotropic drugs.1 The sacred places were often selected through the esoteric

science of geomancy or through a priest’s psychic revelation. The site of these temples was particularly important to the ancient Greeks, for example, because their chthonic deities2 were believed to reside in special locations.

All aspects of the temples themselves were designed to mobilize and heighten the workings of the unconscious mind as well as spirits. For example, in Greece the cult of the oracle god Aesclepius3 was symbolized by the

snake, and dream seekers would often sleep in a place where snakes moved about freely. After the elaborate rituals, Aesclepius frequently appeared to the dreamer as a bearded man or as an animal, and in many instances the individual would awaken cured. At the height of their popularity, these Aesclepian centers for dream incubation numbered in the hundreds.

Instances of healing through rituals such as this are also widespread in contemporary shamanic cultures.4 For example, Richard Grossinger, author of numerous books on dream ethnography, cites Native American sources from among the Crow, Blackfoot, Kwakiutl and Winnebago tribes recounting dreams in which

an animal or bird, such as a snake or loon, appeared and taught cures which when applied in waking life were found to have healing power. Dreams have also inspired important scientific advances. Perhaps the most celebrated of these is the discovery of the molecular structure of benzene by Kekule. His account:

My mind was elsewhere.. .I turned the chair to the fireplace, and fell half asleep. Again the atoms gamboled in front of my eyes. Smaller groups this time kept mostly in the background. My mind’s eye, trained by repeated visions of the same sort, now distinguished larger formations of various shapes. Long chains.. .everything in movement, twisting and turning like snakes. And look what was that? One snake grabbed its own tail, and mockingly the shape whirled before my eyes. I awoke as if struck by lightning; this time again I spent the rest of the night working out its consequences.

The Russian chemist Mendelev discovered the periodic table method of classifying elements according to atomic weight while dreaming. Elias Howe completed his invention of the sewing machine while dreaming. Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity came to him partly in a dream. Other dream-inspired creations include literary masterpieces such as Dante’s Divine Comedy,

Voltaire’s Candide, “The Raven” by Poe and Ulysses by James Joyce. Robert Louis Stevenson was able to formulate stories while dreaming, which he later wrote down and published. Even some popular music compositions by Billy Joel and Paul McCartney have come in dreams. Such unusual dreams

notwithstanding, our society as a whole has lost touch with the art of dreaming. Recently, however, a widespread interest in the creative power of dreams has surfaced, emerging from several divergent disciplines, including science, western depth psychology, the increasing awareness of native cultures, and religion.

Science And Dream Phenomena

The modern scientific description of dream phenomena has followed upon the discoveries in 1952 of Kleitman and his students that dreaming is accompanied by rapid eye movements. Other facts about dreaming have emerged through more recent experimentation. For example, we know that all people dream and that approximately twenty-five percent of sleep is dream time. Dreams are crucial for mental health, dreaming is a right-brain activity, and virtually all

dreams are accompanied by rapid eye movements. Sleep has four stages, or depths, but dreaming occurs only in the first stage. We also know that we move through the four stages of sleep several times in a typical night, and consequently we normally dream many times each night. It has been observed that a person who is deprived of dream time will make up for it in subsequent nights. A greater percentage of sleeping time is spent dreaming as we approach dawn.

Let us focus on the phenomenon of lucid dreams, those unusual dreams in which the dreamer finds him- or herself suddenly self-consciously aware or “lucid” while dreaming. Once frequently dismissed but now scientifically verified, reports of lucid dreaming have existed in literature for thousands of years. For example, Aristotle made the following statement: “.. .for often when one is asleep there is something in consciousness which declares that what presents itself is but a dream.”

5 In the early 1900s a Dutch psychiatrist by the name of Van Eeden studied this phenomenon in a systematic fashion and coined the term “lucid dreaming” to describe it. Before him, the Marquis d’Hervey de Saint Denys had investigated dream phenomena and published his findings in 1867 in the book Dreams and How to Guide Them. In this book Saint Denys described his ability to awaken within his dreams as well as to direct them.

Steven Laberge, a modern researcher of dream phenomena, developed a methodology that utilizes the rapid eye movements (R.E.M.) that accompany dreaming, in order to train lucidity.6 In one study subjects listened to a recording that repeated the phrase “this is a dream” every few seconds. This was played after

the beginning of each R.E.M. period. He then asked his sleeping subjects to signal their lucidity by moving their eyes in a prearranged pattern. Approximately twenty percent of his subjects were able to achieve lucidity in their dream state through this technique. More recently Laberge has invented

a “dream light” device which is worn on the face like a mask and detects the rapid eye movements that are associated with dreaming. The rapid eye movements trigger a lowintensity pulsing red light which can cue the dreamer that he or she is dreaming.

The following account, by a participant in a dream awareness seminar, serves to illustrate the phenomenon of being awake or lucid within a dream: On Wednesday morning, January 13, 1988, I became aware that I was dreaming; and I decided that the best thing to do would be to fly in the sky. I hitched myself to a jet and we went very high into the stratosphere. I then had the jet reverse course so I could hang from it and see the world. I looked down and

saw the earth as a great sphere. Then I dropped my hold and stretched my arms out wide to glide better. I stayed quite high (literally and figuratively) in the sky, in order to realize the immensity and beauty of this vast ocean as seen from above. After a short period I glided down lower, very slowly,

finding myself over a beautiful island. This island view was pleasing to me. It was early morning; quiet and even light allowed for clear sight of the still masts of the many yachts docked at the harbor. Beyond their tall poles and white decks, there stood hillside mountains with homes built right

into them. It was a splendid and majestic sight, the yachts and mountains in clear, even morning light. It was reminiscent of a combination of two places I had been before. In Paxos, Greece there are harbored many yachts, and Martin City, California there are homes built into the hills. I continued to view this sight before I fell into a more general type of dreaming in which I didn’t control the view or determine what I would like to do.

The preceding account is typical insofar as lucid dreams frequently include flying. On some occasions the dreamer is first aware that he or she is flying, and then suddenly becomes lucid. On other occasions the dreamer becomes lucid and subsequently tries to fly. Another common feature that this dreamer

shares with other lucid dreamers is the sense of heightened color and emotion, the sense of participating in an awe some and magnificent experience. Not all lucid dreams are so expansive, however. Kenneth Kelzer, an author and lucid dreamer, comments upon the persistent theme of being within a jail

which characterizes one series of lucid dreams he had. “The symbol of the jail cell in these three dreams provided me with an essential reminder that I am still a prisoner, still working to attain that fullness of mental freedom to which I aspire.”7

Dreams And Depth Psychology

In the past century, the frenzied expansion of industrial technology occurred at a great price. For complex reasons it helped to spawn the great world wars. The wide scale destruction and loss of life resulted in a questioning of values—especially those of a religious and moral nature. Against the specter of apocalypse, the despair of meaninglessness, and the perceived ruins of western religious ceremony, contemporary thinkers sought to understand the workings of the psyche by studying less conscious phenomena such as fantasy and dream—thus developing the approach of

depth psychology. Evoking and developing awareness of unconscious processes was perceived as valuable for healing the weary, confused soul. Sigmund Freud, the founder of modern western psychology, called dream work the “royal road to the unconscious,” and helped reawaken interest in dreaming. Freud’s

seminal work, The Interpretation of Dreams, represented a radical departure from previous contemporary Western psychiatric theory. Freud asserted that dreams are symbolic representations of repressed wishes, most of which are sexual. Through the process of “wish fulfillment” the dreamer released the

“excitement” of the impulse. He thought the dream would typically be organized in a disguised or symbolic way because these wishes or impulses were unacceptable.

Noting that a single dream might represent an enormous amount of personal material, Freud postulated that each character or element of the dream was a condensed symbol. The labyrinth of meaning might be unraveled through the process of free association. Techniques of listing all associations to a dream continue to be widely used among contemporary analysts. Less well recognized is Freud’s acknowledgement of the existence of telepathy within the dream state.

This was published in his lectures on psychoanalysis in 1916.8 Carl Jung was perhaps the first Western psychologist to be interested in

Buddhism9 and Eastern religion. Jung, once a close student of Freud, later broke away from his mentor. Jung explained that he could not accept Freud’s overwhelming emphasis on a sexual root for all repressions, nor his narrow, anti-religious views. Jung considered libido to be a universal psychic energy

whereas for Freud it was simply sexual energy.10

Jung also postulated the existence of a deep, encompassing cultural memory accessible through powerful dreams. He labeled this memory the “collective unconscious” and considered it to be a rich and powerful repository of the collective memory of the human race.

Jung postulated that dreams generally compensate for the dreamer’s imbalance in his waking life and bring that which is unconscious to consciousness. He

noted that individuals function with certain characteristic styles, for example with feeling or intellect, and in an introverted or extroverted manner. If a person were primarily intellectual and his feeling side largely suppressed or unconscious, strong feelings might then manifest more frequently in his

dream life. A feeling type, conversely, might have intellectual dreams in order to compensate for the dominant conscious attitude.

Fritz Perls, founder of the Gestalt school of psychology, proclaimed dreams to be the “royal road to integration.” For Perls, dreaming and the awareness of dreaming

were essential for coming into balance and owning all the parts of one’s personality. He based his dreamwork on the supposition that facets of a dream might all be perceived as projections of parts or personas of the dreamer. Perls’ contribution to dream work and therapy was his keen awareness that

neurotic functioning is caused by disowning parts of oneself. He suggests that we disown or alienate ourselves by projection and/or repression. We may reclaim these unacknowledged aspects of our personalities by enacting or dramatizing parts of a dream. Through this process we recognize more fully our own

attitudes, fears and wishes, thus allowing our individualization and maturation process to proceed unimpeded. The following dramatic example of one woman’s enactment of a dream part in the style of Gestalt therapy will illustrate Perls’ technique of dream work. The woman recounted a dream in which a

small aerosol spray can was one of many items on a dresser bureau, and she dramatized the different items in turn. When she reached the spray can, she announced, “I’m under enormous pressure. I feel as if I’m about to explode.” The enactment of this dream provided swift and clear feedback regarding an unresolved issue in her life.

Another school of contemporary psychology which respects the dream experience is that represented by Medard Boss. Boss considers the dream to be a reality which should be understood as an autobiographical episode. In the process of understanding one’s dreams, Boss would encourage the dreamer to actually

experience and dwell within that unique moment. Not all psychologists acknowledge the great potential for advanced dreamwork. For example, in the phenomenological school as articulated by Bross and Keny, dreams are considered to constitute a “dimmed and restricted world view,” and are “privative,

deficient, and constricted in comparison with waking.” The object relations school as typified by Fairbairin considers dreams to be schizoid phenomena, cauldrons of anxieties, wishes, and attitudes. Certain current scientific theories have also gone further in denying a basic meaningful organizing

principle within the state of dreaming. J. Allen Hobson of Harvard Medical School proposes in his book The Dreaming Brain a “dream state generator” located within the brain stem. The generator when engaged fires neurons randomly and the brain attempts to make sense of these weak signals by organizing them into

the dream story. Others have proposed similarly mechanistic explanations of dream phenomena. Crick and Mitehison suggest that dreams occur to unlearn useless information. Connections which are unimportant and temporarily stored are thus discharged and forgotten.

Alternate theories by Carl Sagan and others that attempt to account for the most famous creative acts which have arisen within the dream state have proposed that such dreams result from uninhibited right-brain activity. According to this theory the left-brain, which is usually dominant during the day, is suppressed during dreams. Consequently, the right-brain is less inhibited and can become spectacularly intuitive and creative. This theory would

account, for example, for Kekule’s discovery of the benzene molecule as an example of the right-brain’s skill at pattern recognition in contrast to the more analytic activity of the left-brain. This theory, although interesting, does not account for all types of telepathic and creative dreams.

John Grant, a specialist in dream research, recently spent considerable effort in providing explanations for dream telepathy. His conclusion after much effort in debunking sensational claims was that only ninety-five percent of dream telepathy and dreams which predict future events might be explicable

according to known laws and science. His subjective statistic and inability to account for the other five percent of unusual dreams which anticipate the future fits in well with Norbu Rinpoche’s theory of dream phenomena. This theory acknowledges both common dreams whose origin are our wishes and anxieties, as well as creative clarity type dreams which arise out of awareness.

Many analytic and scientific approaches still contend that the content of all dreams is merely chaotic or symbolic and comprised of a cauldron of anxieties, wishes and attitudes. Consequently, contemporary Western dream workers do

not generally recognize or understand the possibilities for dream work assumed in traditional societies. While Western depth psychology works with dreams as an approach to individual mental health, its understanding of the possibilities for dream work, though improving, is still limited. The range of these other possibilities and the need for determining priorities appears when we explore dream work systems evolved in other cultures.

Dreamwork In Traditional Cultures

Systems for dreamwork and dream awareness have been found for millennia within Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism, Sufism, and traditional cultures throughout the world.11 These dreamwork systems were and are often still cloaked in secrecy and reserved for the initiate. The recorded dream experiences of traditional peoples whose cultures are still relatively intact may help expand our understanding of the possibilities of dream work and dream awareness, including the phenomena of lucidity, telepathy, and precognitive dreams.

The Australian Aborigines believe in the existence of ancestral beings who are more powerful than most humans, and are considered to have other-than-human physical counterparts such as rocks, trees, or land formations. According to the authors of a comprehensive book on Aboriginal culture, Dreaming, the Art

of Aboriginal Australia edited by Peter Sutton, the spiritual dimension in which these beings have their existence is described as the “Dreamtime.” The ancestors, known as “Dreamings,” may be contacted through dreams, though they are not considered to be a product of dreams. This underscores the Aboriginal

belief in multiple classes of beings and alternate dimensions within which other classes of beings reside. Noteworthy are the Aboriginal beliefs regarding texts, art, and songs that come in dreams. A new song, story, design, or other creative product received in a dream is perceived by the

Aboriginal peoples as a reproduction of an original creation rendered by an ancestor. These artistic gifts are considered to be channeled rather than seen as original creations. Within the tribe the dreamer is revered as a conduit through which the wisdom of the ancestors is received, not as the originator of

this wisdom. According to the myths and dream records of contemporary Aboriginal peoples, artistic products have come in dreams since time immemorial and continue to enrich Aboriginal culture today.

The Senoi people of what is today called Malaysia ostensibly provided a documented instance of a traditional people who placed an unusually high value on

creative dream work. Patricia Garfield in her book Creative Dreaming presents dream techniques attributed to the Senoi by anthropologist Kilton Stewart. According to Stewart, the Senoi focused an unusual amount of attention on dream work and developed sophisticated methods for

influencing and deriving creative inspiration from dreams—through reinforcement, self suggestion, and daily discussion of their dreams. Dr. Garfield summarized the key Senoi dream work goals as follows: confronting and overcoming danger within a dream, accepting and moving towards pleasurable experiences within the dream, and making the dream have a positive or creative outcome. The integrative effects of this work may very well be a cause for a lowered frequency of mental disorder. However, later researchers did not substantiate Stewart’s claim that Senoi society approached a Utopian ideal.12

Presumably the Senoi had strong motivation for developing control of their dreams because of the great premium their tribe placed on these abilities. Contemporary researchers report that the ability to influence dreams towards positive outcomes seems to have effects such as increased self-confidence and creativity.

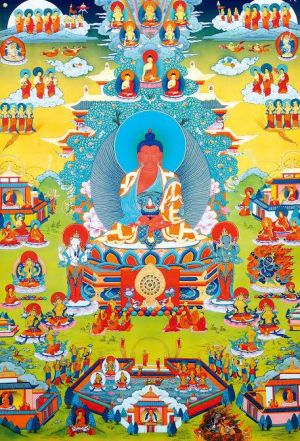

The creative potential of dreams is unquestionably valued in traditional Tibetan culture. Within Tibetan Buddhism there is a class of dreams labeled Milam Ter or “dream treasure.” These treasures are teachings that are considered to be the creations of enlightened beings. The teachings were purposefully

hidden or stored in order to benefit future generations. As a demonstration of their wisdom the originators of these treasures often prophesied the name of their discoverer and the time of discovery. Buddhist and Bonpo systems for dream awareness training appear to be thousands of years old, according to Norbu Rinpoche and Lopon Tenzin Namdak.

14 In the interview presented in this book Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche comments that dream awareness training was discussed extensively in the text of the inconceivably ancient Mahamaya Tantra, whose author is unknown. Khenpo Palden Sherab, a renowned Buddhist scholar,

agrees that the tantras are inconceivably ancient. According to Khenpo, many millennia before the historical Buddha Shakyamuni lived, the tantras were taught by the buddhas of past eras to both human and nonhuman beings.

Consider, for example, the extraordinary dream experience Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche had while on retreat in Massachusetts in the summer of 1990. On night after night a woman whom Rinpoche considered to be a dakini15 appeared in his dream and taught him a complex series of dances with intricate steps for up

to thirty-six dancers. Day after day Rinpoche transcribed the lessons from the dreams of the night before. He also taught a group of his students parts of this dance, which accompany a special song for deepening meditation. The tune itself had been received in another dream years earlier. Having heard firsthand accounts of these dreams, and having participated in this exquisite dance, I can only say that Rinpoche’s experience is profound beyond words. Shortly after Rinpoche’s retreat he was visited by a Native American teacher who goes by the name of Thunder. Thunder is the descendent of a long lineage

of Native American medicine men and healers. After hearing accounts of Rinpoche’s dance and examining photos of our attempts to learn it, she noted its similarity to the Native American Ghost Dance.

The following series of dreams related by Norbu Rinpoche may serve to illustrate the human potential within the dream state as awareness develops. In

1959 I had already fled Tibet to the country of Sikkim. The situation within Tibet was deteriorating rapidly. As the news of killings and destruction reached us I became increasingly worried about the members of my family who remained in Tibet. Many of us prayed to Tara asking for her help. It was during this period that I had the following dream:

I was walking through a mountainous area. I remember the beautiful trees and flowers. Near the road on which I was traveling there were wild animals, but they were peaceful and gentle to me. I was aware that I was enroute to Tara’s temple located on a mountain ahead. I arrived at a place near the temple,

where there was a small field with many trees and red flowers. There was also a young girl approximately eleven or twelve years old. When the young girl saw me she immediately gave me a red flower, and inquired where I was going. I replied, “I am going to the temple of Tara in order to pray for Tibet.” In response she said, “There is no need for you to go to the temple; just say this prayer.” She then repeated a prayer to me many times that began, “Om

Jet-summa....” I began to say this prayer, repeating it as I was holding the flower. I repeated the prayer again and again. I actually woke myself up by

saying this prayer so loudly. Some years later I had a related dream. In this dream, I again found myself in the field that marked the approach to the temple of Tara. It was the same as the previous dream, but there was no young girl. I looked ahead of me, and there was the temple at the top of a mountain. I continued my journey until I arrived. It was a simple temple, not elegantly designed or decorated. It was open to the East.

I entered and noticed that upon the wall was a painting of the Shitro mandala of the one hundred peaceful and wrathful deities. On bookshelves there were many Tibetan books, including the Tanjur and Kanjur. I was looking over the collection when I noticed a Tibetan man at the door. He was dressed somewhat

like a lama, but not completely. He asked me, “Did you see the speaking Tara?” I replied that I had not yet seen the speaking Tara, but that I would like to. The man then led me to a room with statues. As he turned towards the door to leave, he said, “There is the speaking Tara.” I didn’t see anything

at first, but then I noticed that the man was looking upwards to the top of a column. I followed his gaze, and there at the top of the column was a statue of Green Tara. She was represented as a child of perhaps seven or eight years. It was a nice statue, but I didn’t hear it speak, and subsequently I

awakened. The next chapter in this story was not a dream at all. In 1984 I was traveling in northern Nepal heading towards Tolu Monastery, when I recognized the field where in my dream the girl had given me the flower and prayer. I looked ahead and there was the temple. When I arrived, everything was

exactly the same as in my dream. I walked over to the column, and looked for the “speaking Tara.” It wasn’t there. That was the only detail that differed. Not too long ago, I heard that one of my students had presented the temple with a statue of Green Tara which they placed on top of the column as a sort of commemoration. If you travel to that temple today you can see it there.

Developing Dream Awareness

The possibility of developing awareness within the dream state and of subsequently having intensely inspiring experiences as well as the ability to control dreams is well documented. It is the pathway to higher order dreaming made possible by the practices outlined later in this book.16 Cross-cultural

parallels point very strongly to the existence of a class of dream experiences which have fueled the advance of mankind’s cultural and religious progress. These dreams, which Norbu Rinpoche refers to as clarity dreams, seem to arise out of intense mental concentration upon a particular problem or subject, as well as through meditation and ritual. Startling, creative or transcendent outcomes often emerge from these special dreams, some of which may be channeled.

In a dream awareness seminar I conducted in 1989, a participant recounted the following dream: “When I was a young child I used to have a recurring dream of being threatened by an old ugly dwarf who was terrifying to me. Each time he would appear I would either run away in that nightmarish manner of not seeming to get anywhere, or pretend to faint just to get away from him. Finally during one dream I became very annoyed and decided I was tired of being

threatened. I turned on him and told him he was just part of my dream. When I did that I wasn’t frightened of him anymore. The dream never recurred after that.” Even my own relatively minor dream experiences have occasionally seemed to support the possibility of dreams that predict the future. For

example, last year I attended a sporting event with two friends. I was impressed by the colorful stadium. That night I dreamt of a baseball player. His picture was on the front page of a newspaper. I tried to read and remember the print. By the next morning I only recalled the name Clark. Upon awakening I

purchased the New York Times, as is my habit, and discovered a photograph of Will Clark, a baseball player, on the front page. Perhaps you might argue that this was coincidental. If so, you would be making the same argument that Aristotle used in order to counter Heraclitus who believed in precognitive

dreaming (just to illustrate how long the controversy has raged). Regardless of whether my dream about Will Clark was truly prophetic, I personally have come to believe that within the higher order creative class of dreams, there is a category predictive of the future. If this is actually the case it

would suggest that the future is somehow available in the present. Within Tibetan Buddhist, Bonpo, and other traditions, enlightened beings are considered to have the capacity to see the past, present, and future.

If there is indeed significant evidence of a class of higher order dreams, questions arise concerning how one may develop the capacity for them and whether

or not there are reasons (beyond their ability to increase creativity) to cultivate this capacity. According to the Tibetan Dzogchen tradition, the key to working with dreams is the development of greater awareness within the dream state. It is this degree of awareness that differentiates ordinary dreaming from the ultimate fruit of total realization with the dream state. Norbu Rinpoche discusses this difference in his chapter on the practice of the natural light.

Over the course of a typical night, as much as eight hours may be spent sleeping, of which two or more hours might be spent dreaming. Are we able to remember dreams from each of these sessions? How precisely do we remember details? An individual with no awareness of her or his dreams, who is largely

unable to remember, has sacrificed awareness of a large portion of her or his life. This person is missing the opportunity both to explore the rich and fertile depths of the psyche as well as to grow spiritually. Consider the message of this Buddhist prayer:

When the state of dreaming has dawned, Do not lie in ignorance like a corpse.

Enter the natural sphere of unwavering attentiveness.

Recognize your dreams and transform illusion into luminosity.

Do not sleep like an animal. Do the practice which mixes sleep and reality.

There is no doubt that lucid dreams and clarity experiences are fascinating occurrences which seemingly have positive benefits for self-esteem, integration of personality, and overcoming of fear. It is also critical to place their occurrence within the context of the quest for spiritual transformation or enlightenment. Insofar as a culture such as ours tends to value experience for experience’s sake, there is the danger of missing the forest for the trees.

One lama from the Tibetan Buddhist tradition likened the pursuit of lucid dream experience to mere play and games except when it arises as the by-product of an individual’s development of meditative clarity through the Dzogchen night practice of the white light or Tantric dream yoga. Although there does seem

to be relative value in lucid dream experience, from the Buddhist perspective its usefulness is limited unless the individual knows how to apply the lucid awareness in the after-death states of the Chonyid and Sipa Bardos.

In the Dzogchen school, which for millennia has been familiar with lucid dream experiences as well as such parapsychological phenomena as telepathy and precognition, there is the constant advice from teacher to student that one must

not be attached to experience. This counters the Western trend to value experience for its own sake. Western approaches also encourage a systematic analysis of the content of dreams, whereas Dzogchen teachers encourage practitioners not to dwell upon dream phenomena.

Although there seem to be clear relative benefits from the extensive examination of dream material, it is quite possible that these benefits are only for the beginner. For the advanced practitioner, awareness itself may ultimately be far more valuable than the experience and content, no matter how creative. Great teachers have reported that dreams cease completely when awareness becomes absolute, to be replaced by luminous clarity of an indescribable nature.

The presentation of techniques for dreamwork from these ancient traditions is important because these traditions are in danger of extinction. Although there have been many books written on the general topic of dreams, there has still been relatively little that would serve to bring dream work into the

spiritual context. Buddhist, Bonpo and Taoist teachers have acknowledged to me that this situation has influenced their decisions to teach more openly. In a personal way, this project served to focus my attention on the power and richness of maintaining awareness during the often-neglected sleep time.

Regardless of our material circumstances, if we cultivate this capacity we possess a wish-fulfilling jewel. In the West the scientific exploration of sleep and dreams is quite new, but within the larger community of humankind the arcane science of dream awareness and exploration has been cherished for

millennia.

Pioneer psychologists of the twentieth century have commented upon dream phenomena. Sigmund Freud called dreams “the royal road to the unconscious,” and Fritz Perls called them the “royal road to integration.” In their way these assertions may be true, but they are overshadowed by the

possibility that the awareness of dreams is a path to enlightenment. I am grateful for the opportunity to help chronicle the extraordinary dream experiences and teachings on the dream state of Dzogchen master Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche.

1. Psychotropic drugs affect the mind, sometimes inducing visions or hallucinations. Used by shamans in native cultures to make contact with the spirit world, the drugs are frequently employed to assist in rituals for healing. Examples of such drugs are peyote and certain types of mushroom and cactus. [return]

2. Chthonic deities were considered to live below the earth and were associated with agriculture and the fertility of the land. They were worshipped by the pre-Greek speaking people who were of a matriarchal culture. These deities may be related to the local guardians whom the Tibetans believe reside in specific locations. [return]

3. Asclepius (called Aesculapius by the Romans) was considered to be a son of Apollo and was raised by the immortal centaur Chiron in his cave. Aesclepius became a great physician and left Chiron’s cave to help the people of Greece. As he was a remarkable healer, the Greeks ultimately worshipped him as a god and built temples to honor him. Inside these temples Asclepius ostensibly put beds for the sick, thus establishing the first hospitals. He walked about with a stick entwined with sacred serpents (the modern symbol for medicine), who were said to know the causes and cures of disease. Sometimes he put his

patients to sleep with a “magic draught” and listened to what they said in their dreams. Often their words explained what was causing the ailment, and from this information he could offer a cure. Priests continued to invoke him after his death, and he continued to appear in dreams of those who were ill, offering them healing advice. [return]

4. The word shaman is a Siberian term deriving from the classical form of shamanism in North Asia. Through rituals, chanting, drumming and psychotropic drugs, shamans go into trance for the purposes of healing and of divination. [return]

5. From The Works of Aristotle Translated into English, ed. W.D. Ross (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1931), Vol. 1, Chapter 1, “De Divinatione Per Somnum,” p.462a. [return]

6. Laberge, Kelzer and other dream researchers have sought to develop and compile methods for inducing lucid dreaming. These include entering lucid dreaming directly through focusing on naturally occurring hypnogogic imagery which occurs prior to the onset of sleep (see Kelzer, The Sun and the Shadow,

page 144), and auto-suggestion that the dreamer will immediately become lucid upon recognizing incongruities within the dream state. For example, the editor recently had a dream in which he noticed that both a man and a dog who had attempted to jump from one roof to another and missed were falling in a

way that was incongruent with the laws of gravity. The awareness of this incongruity sparked a lucid dream. Other methods include a variety of ways to utilize autosuggestion, the intention that one will be lucid in one’s dreams. Steven Laberge (see Lucid Dreaming, pages 48-78) has been particularly

active in systematizing these techniques. His mnemonic induction of lucid dreams (MILD) technique entails awakening during the night after dreaming, focusing on the details of the dream, particularly the incongruities, and making a strong suggestion that if an incongruity or dream sign reappears one

will immediately become lucid. In this technique one holds the intention to become lucid immediately prior to returning to sleep. Laberge reports that the effectiveness of this technique is enhanced by the simultaneous use of technological devices such as his dreamlight goggles which flash low intensity light with the occurrence of the rapid eye movements that characterize the onset of dreaming.

Another technique discussed by various dream researchers, including Paul Tholey, involves state testing. This term refers to the practice of asking oneself if one is dreaming at frequent intervals during the day, while concurrently analyzing the situation to attempt to be sure of the answer. The “critical state testing” (Lucid Dreaming, page 58) in many cases subsequently leads to a similar testing process within the dream, and then to lucidity.

These techniques that attempt to induce lucidity contrast with the practice of natural light found within the Buddhist, Bonpo and Dzogchen traditions as discussed by Norbu Rinpoche, which does not particularly focus on developing lucidity but considers lucidity a natural byproduct of the development of awareness and presence. [return]

7. The descriptions of lucid dream experience as awesome and liberating or, alternatively, Kelzer’s lucid dream experience of being in prison, which served to remind him of the need to work to attain “that fullness of mental expression to which I aspire,” seem to echo themes within Plato’s “Allegory of

the Cave.” In this classic of philosophy, Plato described cave dwellers who have become accustomed to the shadowy muted reality of life within a cave. The inhabitants are unaware of the possibility of a more vibrant, spectacular reality, and doubt the probability of the sun. Descriptions of lucid dreams

that include an unusual intensity, richness of color, and other sense impressions may suggest a “taste of enlightenment.” Perhaps the dreamer has momentarily broken the habitual conditioned modes which typically govern perception, referred to within the allegory as living within a cave. [return]

8. In addition, there is support for the contention that Freud knew about lucid dreaming and made reference to types of lucid dream experience. See “Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis” in The Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, standard edition (New York: Hogarth Press, 1916), Vol.15,

p.222. This evidence is summarized by Bol Rooksby and Sybe Tenwee in their historical article published in Lucidity Letter, 9 (2) 1990, Edmonton, Alberta. [return]

9. Jung’s interest in Buddhism and eastern philosophy was great enough for him to have written the foreword for the first translation of the classic Tibetan Buddhist book of the dead, the Bardo Thodol. Unfortunately, due to mistranslations within the original publication of the Tibetan Book of Great Liberation by Evans Wentz, Jung never had a clear understanding of the Dzogchen great perfection teaching with which the text was concerned. Evans Wentz’s faulty understanding of the Dzogchen subject matter led to his improper translations, such as that of the “primordially pure nature of mind” as the “one mind.”

Jung subsequently misinterpreted “the one mind” as referring to the unconscious, which it does not. The pure nature of mind was a reference to the pinnacle teaching of Buddhism, Dzogchen. The flavor of Dzogchen practice is later described in this book by Namkhai Norbu, and also within an original text by the

Tibetan meditation master Mipham (1846-1914). For a thorough discussion of the aforementioned misunderstanding, the reader is referred to the recent retranslation of the Tibetan Book of the Great Liberation by John Reynolds. [return]

10. It is unclear to what extent Jung was influenced in his conception of universal psychic energy by Tantric Buddhist and Taoist theories of internal energy, called “lung”, “prana” and “chi” in Tibetan Buddhism, Hinduism and Taoism, respectively. Within the Tantric system of Anu Yoga, “lung” or

internal airs are said to circulate through internal channels or meridians called “tsa”. According to Norbu Rinpoche and other lamas within the Dzogchen tradition, “lung” may be purified and caused to circulate along specific internal

paths. The methods for achieving these ends are elaborate breathing exercises and physical exercises. Collectively, these exercises are called Yantra Yoga, or Tsa Lung. [return]

11. It is now clear that there are many so-called primitive peoples with sophisticated ways of interpreting and manipulating dreams. What seems likely is that for thousands of years a few initiates in widely diverse cultures have practiced dream manipulation, lucid dreaming and more, while most of the population—then as now—slept unconsciously. [return]

12. Krippner, S., Dreamtime and Dreamwork, Preface to Chapter 5, pages 171-174. [return]

13. Bonpo/Yung-drung Bon: The teachings found in the Bonpo school derived from the Buddha Tenpa Shenrab, who appeared in prehistoric times in central Asia. Bon means teaching or dharma, and Yung-drung means the eternal or the indestructible. Yung-drung is often symbolized by a leftward spinning swastika. The leftward direction is representative of the matriarchal roots of Tibet (the left being related to feminine energy, the right to masculine). The Yung-drung is a symbol of the indestructibility of the Bon teachings just as the dorje/vajra/diamond scepter is the symbol of the Tantric Buddhist teachings. It

is important to note that the Yung-drung bears no ideological relation or similarity to the Nazi swastika symbol. Yung-drung Bon is also known as “New Bon.” Lopon Tenzin Namdak distinguishes two stages of the development of Bon. The first stage is the most ancient “Old Bon,” or “Primitive Bon,” which

is similar to North Asian shamanism. The second stage is Yung-drung Bon with its roots in the teachings of Buddha Tenpa Shenrab. Tenzin Namdak was born in Eastern Tibet and educated at Menri, the leading Bonpo Monastery in Central Tibet. In 1959 he became a Lopon, head of academic studies, and led an

exodus of Bonpo monks from Tibet to India to escape the Communist Chinese. In the early 1960s he organized the Bonpo community in Dolangi, Himachal Pradesh, and built a monastery and a lama college there. He currently resides there as the head teacher and is the foremost native Bonpo scholar amongst

Tibetans in exile. Lopon Tenzin Namdak was the informant for David Snellgrove’s Nine Ways of Bon. Lopon lived in England for three years in the 1960s and speaks fluent English. [return]

14. Lopon Tenzin Namdak, a meditation master who heads the Yung-drung Bon sect of the Bonpo religion, claims that the Bonpo spiritual tradition—including its dream awareness practices—may be traced back 18,000 years to an area that includes western Iran and western Tibet. According to the Bonpo

history, a superhuman being, Tenpa Shenrab, who incarnated at that time, was the originator of their religious system. For comparison, archeologists cite evidence of religious activity—burying the dead with objects— from 30,000 B.C. Further perspective may be gained by noting that the archeological remains of Cro Magnon man, which have been found throughout Africa, Europe, and from Iran to Asia, date from 100,000 B.C. [return]

15. Dakini: Tibetan, Khadro. Kha means space, sky; dm means to go. Thus the term indicates a sky/space goer. The dakini is understood to be the embodiment of wisdom, and is ultimately beyond sexual distinction but is perceived in female form. There are many classes of dakinis including wisdom dakinis, who are

enlightened. Examples of these are Man-darava, Yeshe Tsogel and Vajra Yogini. There are also flesh-eating dakinis, as well as worldly dakinis, who embody worldly female energy. Dakinis represent the energy that allows teachings to be taught. [return]

16. Included later within this book are a series of dreams by Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche which he recorded while making pilgrimage to Maratika Cave in Nepal. On the pilgrimage, Norbu Rinpoche dreamed of a text more than 100 pages long, which included instructions for advanced meditation practices. Spectacularly creative dreams such as these are subsequently referred to as dreams of clarity.