Shankara: a hindu revivalist or a crypto-buddhist?

Georgia State University

ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University

Religious Studies Theses Department of Religious Studies 12-4-2006

Kencho Tenzin

Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ [[Georgia State University\\.

For more information, please contact scholarworks@gsu.edu.

Recommended Citation

Tenzin, Kencho, "Shankara: A Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?" (2006). Religious Studies Theses. Paper 4. SHANKARA: A HINDU REVIVALIST OR A CRYPTO BUDDHIST?

by

Under The Direction of Kathryn McClymond

ABSTRACT

Shankara, the great Indian thinker, was known as the accurate expounder of the Upanishads.

He is seen as a towering figure in the history of Indian philosophy and is credited with restoring the teachings of the Vedas to their pristine form.

However, there are others who do not see such contributions from Shankara. They criticize his philosophy by calling it “crypto-Buddhism.”

It is his unique philosophy of Advaita Vedanta that puts him at odds with other Hindu orthodox schools.

Ironically, he is also criticized by Buddhists as a “born enemy of Buddhism” due to his relentless attacks on their tradition.

This thesis, therefore, probes the question of how Shankara should best be regarded, “a Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?”

To address this question, this thesis reviews the historical setting for Shakara’s work, the state of Indian philosophy as a dynamic conversation involving Hindu and Buddhist thinkers, and finally Shankara’s intellectual genealogy.

Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in the College of Arts and Sciences

Georgia State University

Major Professor: Kathryn McClymond

Committee: Jonathan Herman

December 2006

ACKNOWLEDMENT

In the process of writing this thesis, many people have helped me, both directly and indirectly. Their ideas, suggestions, and queries were the source of my inspiration. This thesis could not have been completed without their assistance. First, my heartfelt appreciation goes to Dr. Kathryn McClymond, my thesis advisor, for her guidance and inspiration in writing this thesis and also her unwavering support throughout my graduate school years at Georgia State University.

My special thanks also go to Dr. Susan Walcott and Brendan Ozawa whose encouragement and support have been both valuable and indispensable. I am also very grateful to my father-in-law, Dr. Arun Chatterjee, for showing me the underlying tenets of different Hindu philosophical schools, particularly of Advaita Vedanta of Shankara.

I would like to thank my thesis committee members, Dr. Jonathan Herman and Dr. Christopher White, for their insightful comments, suggestions, and teachings as well. Finally, but most importantly I would like to thank my wife, Rinku, for her selfless support, without whom I would have never done this.

Introduction

Introduction

One of the best known figures in the history of Indian thought, Shankara has been credited with restoring the study of Vedas, especially Advaita Vedanta to their pristine purity, and he is also widely regarded as an accurate expounder of the Upanishads. As George Cronk (2003) says, “Shankara is a towering figure in the history of Indian philosophy” (1). The same notion prevails in Surendranath Dasgupta’s Indian Idealism (1962), where he says, “The most important interpretation of Upanishadic idealism has been that of the Brahmasutras as expounded by Shankara and as further elaborated by his followers” (149).

In sharp contrast to such accolades, well-regarded scholars such as C. D .Sharma, S.G. Mudgal, and Ninian Smart do not view Shankara’s thought as innovative. According to them, Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta philosophy did not differ significantly from Mahayana Buddhism. Mudgal (1975), for example, points out in the introduction of his book Advaita of Shankara–A Reappraisal that “the difference between Sunyavada (Mahayana) and Advaita is a matter of degree and emphasis and not a matter of difference in kind” (4). “Probably because of these similarities,”

Natalie Isayeva (1993) says, “even such an astute Buddhologist as Rozenberg was of the opinion that a precise differentiation between Advaita Vedanta and Buddhism is impossible to draw” (172). For this very reason, Ramanuja, the founder of the Visistadvaita Vedanta School and other orthodox Hindu schools, went so far as to describe Shankara as a “crypto-Buddhist.” Yet at the same time, ironically, Shankara is criticized by Buddhist scholars as a “born enemy of Buddhists” due to his relentless attacks on their tradition. Sengaku 2

Mayeda (1999) says, “Sankara, however, vehemently attacks Buddhism here and there in his Brahmasutrabhasya, Brhadaranyakopanisadbhasya, Upadesasahasri and his other works” (n.p.). Shankara, for instance, accuses Buddhism for sowing the general sense of pessimism in people’s mind. Shankara argues that Buddhism (Mahayana) is vainasikamata, a teaching of non-existence and destruction.

Shankara even portrays Buddha’s teachings as a means to lead the wicked and the demons astray despite his inclusion of Buddha as the ninth avatar of Vishnu (Hindu god). Gavin Flood (1996) says, “The Buddha is a curious inclusion in this list: an incarnation sent to lead the wicked and the demons astray and so to hasten the end of the current age of darkness (kali yuga)” (116).

These are some of the few instances that clearly demonstrate Shankara’s attitude towards Buddhism. One reason, according to F. Whaling (1979), for Shankara’s reaction against Buddhism is “the undue Buddhist influence he felt he had received from Gaudapada” (23).

This raises the key question that will be addressed in this thesis: is Shankara best regarded as a “crypto-Buddhist” or as a “born enemy of Buddhism?”

According to Shankara, in his time sanatana dharma (eternal teaching, tradition, or religion) had been almost broken within the entangling of Buddhist philosophy, which had given rise to a general sense of pessimism amongst the general population.

Hinduism, on the other hand, was disunited and had split into many groups and sects, each with its own views. Both Hindu and Buddhist communities were showing signs of corruption, disintegration, and a lack of inner dynamism in appealing to the general public.

A philosophical emptiness prevailed, and society was in need of correct spiritual direction. It was in this atmosphere that Shankara was keen to stress the importance and correct interpretation of the Upanishads. As T.M.P. Mahadevan (1968) says, “At the time 3

when false doctrines were misguiding the people and orthodoxy had nothing better to offer than a barren and outmoded ritualism to counteract the atheism of the heterodox, Shankara expounded the philosophy of the Upanishads for the benefit of humanity” (285). A similar conclusion is also made by Isayeva in her book, Shankara and Indian philosophy. She says, “His [Shankara’s] task was to curb the activity of ‘heretics’, to put an end to mental instability in general and what was of no less importance–to set limits on ritual trends within a former brahmanist unity, submitting it to a new kind of spiritual kind” (11).

However, it seems that while Shankara did assimilate some teachings of Buddhism into his Advaita system, at the same time he denied and refuted Buddhist concepts that were not in agreement with the Upanisads. For instance, he embraced the practice of ahimsa (non-violence) and condemned animal sacrifices. However, he vehemently criticized the central Buddhist doctrine of sunyata (emptiness).

Regarding orthodox Hinduism, Shankara believed that early Vedantins, such as Ramanuja and Madva, failed to grasp the real nature and meaning of the philosophy of the Vedanta as taught in the Upanishads. According to Shankara, pre-Shankara Vedanta was theistic and realist. It conceived of Brahman as unity-in-diversity, with internal individual distinctions being admitted. In mukti (liberation), the jiva (individual soul) retains its individuality.

These views were not palatable to Shankara, and in contrast he taught the doctrine of nondualism (Advaita). According to Shankara, in the state of mukti, an individual is absorbed in the Brahman. By embarking in this direction, Shankara created a new form of Indian philosophy quite different from his predecessors.

Although Sankara’s time seems far removed from ours, and the differences and similarities between his thought and that of Nagarjuna’s tradition may not seem of great relevance today, there is actually quite a bit at stake in how we view him.

We find today a growing interest in Indian traditions of philosophy and meditation in the west and a corresponding proliferation of teachers of various traditions. Perhaps because the transmission of these traditions to the west remains at a relatively early stage, or perhaps because of the influence of a New Age style of thinking, often the philosophical nuances of these traditions are downplayed. Many of these traditions use a similar set of terms and concepts, such as karma, moksha, reincarnation, and so on, and it is easy for those unfamiliar with the subtleties of their respective philosophies to think that these traditions all ultimately boil down to the same thing.

Sometimes we even find popular teachers in the west saying just that, as in a recent talk given at Tibet House jointly by Robert Thurman and Deepak Chopra, two of the most popular exponents of Tibetan Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta in the US. Both teachers drew attention to the similarities between the two traditions, and Prof. Thurman explicitly stated that there was no real difference between Buddha Dharma and Advaita Vedanta.

He says, “It is only some semantic confusion people attach to it” (“God and Buddha: A Dialogue,” 2000). Whether this is true or not might not be very important if these were traditions that merely involved theory and philosophy, but they are at their roots traditions that are fundamentally about practice for self-cultivation and liberation.

Most serious scholars and practitioners of these traditions would probably agree that a correct philosophical view is not an end in itself, but serves to enable one’s practice to be effective. If this is so, then philosophical differences do matter and are not merely 5

academic. And if that is the case, then there is danger in papering over those differences and presenting diverse traditions as all being basically the same, even if this appeals to contemporary American culture.

In Indian religion, theory and practice are closely related, and there is a great diversity in terms of methods of self-cultivation and meditation. How one viewed oneself and ultimate reality would have to correspond with one’s practice of meditation. In America today, on the other hand, despite its growing popularity “meditation” is often seen as a single, relatively straightforward activity for relaxation, rather than a category encompassing a broad range of practices.

If these philosophies and practices are really about self- transformation, and if they are to be properly transmitted to the west, then a greater attention to detail to both theory and practice will be necessary, and generalizations will have to give way to more subtle analyses of difference. In this context, it remains important that one investigate the claims made by many teachers and scholars that Advaita and Mahayana Buddhism are basically the same philosophy, and for this reason a serious investigation of Sankara is essential. This thesis, therefore, probes the question of how Shankara should best be regarded, and argues that Shankara is best characterized not as a Hindu thinker or a “crypto- Buddhist,” but as an Upanishadic Indian philosopher.

This characterization best reflects the historical setting for his work, the state of Indian philosophy as a dynamic conversation involving Hindu and Buddhist thinkers, and finally Shankara’s intellectual genealogy. To investigate this question, the initial section of this paper examines Shankara’s historical and geographical context, particularly the region of Northern India where Shankara spent most of his life teaching and gathering disciples. As K. Damodaran 6

(1967) says, “the main centers of his [Shankara’s] activities were in North India” (247). This section also highlights the political, economic, and social changes in and around that region and their impact on religious beliefs, ethics, and philosophical outlook of the people at the time.

The second section focuses on the dynamics of the relationship between Shankara and his teacher, Gaudapada, and on Gaudapada’s influence on Shankara’s life. As a result, it reveals the important but limited influence of Buddhism on Shankara’s teachings. The third section will explore the key philosophical concepts Brahman, maya, jiva, Atman, avidya, and moksa from the perspective of Shankara’s writings and commentaries on Shankara’s writings. It investigates in what ways Shankara’s thought remained traditional, original, and individually distinctive at the time.

The fourth section assesses the arguments of scholars such as Mudgal, Sharma, Smart, and others, who fundamentally suggest that Shankara’s Advaita system is no different from the Sunyavada system of Nagarjuna (150-250 CE). It analyzes the reasons why, and on what basis, these claims are made.

Finally, the last section responds to the arguments of these scholars by demonstrating that Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta is neither an imitation of Mahayana Buddhism nor contrary to orthodox Hindu schools. In fact, it is an assimilation of contemporary Buddhist thought, Hindu thought, and Shankara’s own interpretation of the Upanishads. It is therefore a unique system initiated by Shankara. The previous sections detailing Shankara’s historical background, his own philosophical position, the contentions by his critics, and my response to them, will all combine to demonstrate that this conclusion seems the best way to regard Shankara in the context of Indian thought. 7

I.

Historical background

According to tradition, Shankara lived from 788-820 CE, only thirty-two years. Despite the brief span of his life, Shankara’s achievements were truly extraordinary. As noted, he is credited as the author of many commentaries and he is also widely regarded as an accurate expounder of the Upanishads.

According to K. Damodaran, Shankara expounded a new idealist system of monistic philosophy known as Advaita Vedanta or absolute non-dualism. Damodaran says, “The Advaita of Shankara was certainly not a mere restatement or exposition of the doctrines of the Upanishads, the Gita and the Brahma Sutra. He revised some of the old concepts, added some new ones and enriched Indian idealist philosophy with many original contributions, though he claimed to have based his system of thought on the Upanishadic metaphysics” (248). (This will be discussed more fully in a later section).

Among his writings, the most important works are Brahman-sutra-bhasya (commentary on Brahmasutra) and commentaries on the Upanishads and the Bhagavadgita. His extensive writings having survived into our own time, so we know a great deal about his philosophy. However, very little reliable information about the details of his life is available. There are numerous traditional biographies of Shankara, but these were all written long after his time, and they contain small bits of historical fact mixed with substantial amounts of fable, legends, and hagiography. Shankara was born in southern India in the village of Kaladi, on the Malabar Coast (now part of the state of Kerela, South India) of brahmin parents. His father, Shivaguru, died when Shankara was still a young boy. Tradition says that Shankara displayed a 8

remarkable intelligence as a child and a spiritual disposition.

He was not only able to read, but had memorized all the scriptures at the very young age. Marrying, raising a family, and living the life of a householder were not his desire from the beginning. The death of his father, seem to have prompted him to think more about spirituality, and it especially made him wonder about the mystery of life and death The poem “Moha Mudgaram” (The Shattering of Illusion), believed to have been written by Shankara, illustrates this:

Birth brings death, death brings rebirth:

This evil needs no proof.

Where then, O Man, is thy happiness?

This life trembles in the balance

Like water on a lotus leaf-

And yet the sage can show us, in an instant,

How to bridge this sea of change.

At a very young age he renounced the world and became a sannyasin (wandering ascetic) in search of the meaning of existence. He met Govindapada, a great learned sage, by the bank of Narmada River. Govindapada taught him the philosophy of Advaita which he learned from his own guru, Gaudapada. Shankara learned all the philosophical tenets from Govindpada and eventually traveled north to Varanasi.

There, Flood says, “He taught, gathered disciples, and debated with other thinkers” (240). In Varanasi Shankara wrote all his famous commentaries. Mahadevan eloborates, “After his trip to Badarikarsrama in the Himalayas he returned to Banaras (Varanasi), and wrote his 9

commentaries on the Upanishads, the Bhagavad-gita, and the Brahma-sutra, as also his commentary on the Visnu-saharsranama and other independent manuals” (284). According to Mahadevan, Shankara grew up during a time of unrest and strife, of spiritual bankruptcy, and of social discord.

He says, “At Shankara’s time there were literalists and ritualists who were holding on to the scriptures, missing their spirit, and there were nihilists and iconoclast who were out to destroy all that was sacred and old” (13).

It was an age of conflict among the different schools of philosophy and hostility among the religious sects, a medieval period, as Donald H. Bishop (1975) says: “the period” of “both continuity and changes” (277).

Dates for the beginning and the end of the medieval period of India are debated. Historians have set different demarcation lines. According to Damodaran, the imperial period of Gupta Kings (320 BCE-500 CE) demarcates the end of ancient period and the beginning of the medieval age in Indian history. This period is particularly remembered in Indian economic and cultural history as the period when feudal ownership of property first appeared.

However, the collapse of the Gupta dynasty, around 500 CE, and the invasion of the Huns from the North, resulted in social and political disturbance with tremendous philosophical and religious changes in India. During this period of far-reaching economic and social changes, India saw the rise and establishment of many feudal kingdoms.

For example, Emperor Harsha (606 CE-647 CE) established his kingdom at Kanauj, Punjab, and expanded his territory to the Bay of Bengal. Other clans like the Palas in Bengal, the Chandels in Bundelkhand, the Abhiiras in Gujarat and so forth were also established during this time. Thus, the establishment of 10

changes in, or the expansion of different manifestations of, feudalism encouraged the village community to develop as a unit of diverse groups. Changes in the economic structure in general, and village community in particular, were accompanied by changes in the social customs, religious beliefs, ethics and philosophical outlook of the people.

Brahmanism and varnasrama, for example, arose during the disintegration of old tribal communalism and the emergence of slavery. For instance, in the earliest period, there were no signs of class division among Aryans; rather they lived a communal type of life. Property such as cows, goats and other livestock were owned in common. Land cultivation was also conducted under common ownership. For the purpose of production and distribution, efficient and strong individuals were elected as leaders of the tribes. Thus, in the absence of class divisions, claims Damodaran, the people enjoyed equality.

However, economic growth and increased wealth compelled a division of labor within the community. Each social activity increasingly required specialized leadership. As a result, some started providing leadership in battle, while others were able to lead agricultural operations, and others performed religious rites for protection. These people emerged as different types of leaders in the society. Those not able to perform these tasks worked in different sectors of productive activity such as agriculture, handicrafts and so forth. According to Damodaran, this division of labor, specialization and so forth resulted in the break-up of the old social system based on common production and common ownership. Wealth and power drifted into the hands of the few elected leaders and priests. These material conditions, he argues, gave rise to the institution of the four varnas: brahmins, kshatriyas, vaisyas, and sudras.

These divisions of society were based on functional attributes. Each varna had its own duties and responsibilities. This demarcation of rights and duties governs the social relations between the classes. The brahmins occupied a highly respected and important position followed by kshatriyas and vaisyas. The sudra was constituted as the lowest of the varnas. Only the menial service of the other three varnas was allowed for sudras. The varnashrama system thus implemented strict discipline and observance of svadharma (class duties).

It was, in fact, mainly as a revolt against brahmanism that the Buddha and his teachings appeared in India. Damodaran says, “Buddhism was anti-priest in its outlook and opposed to ritualism, and hence it was found to be more advantageous for the new times than brahminism with its accent on the varnasrama inequalities and the privileged position of the priests” (108). According to Flood, the era also witnessed the emergence of a new ideology of renunciation, which gave preference to knowledge (jñana) over action (karma) and detachment from the worldly concern by cultivating ascetic practices (tapas), celibacy, poverty and methods of mental training (yoga) (81). The path of world-renunciation offered the renouncer an escape route from worldly suffering, as well as from worldly responsibilities, and a life dedicated to finding understanding and spiritual knowledge, a knowledge which was expressed and conceptualized in various ways according to different systems. Having abandoned worldly concerns, the renouncers practiced asceticism (tapas) to attain moksa (liberation). Asceticism took the form of a severe penance, such as vowing not to lie down or to sit for twelve years and so forth. However, an ascetic was particularly encouraged to practice 12

yoga in order to achieve a state of non-action: to still the body, still the breath, and, finally to still the mind.

These new ideologies of renunciation were emerging in northern India and especially in Varanasi, the center of learning. This is where Shankara dedicated most of his life to writing commentaries, teaching, gathering students, and debating with philosophers in other traditions. Isayeva says, “It was there (Varanasi) that the preaching of the Advaitist expanded” (80).

Varanasi (Banaras) is a beautiful city located on the western bank of the River Ganges. The city is also called Kashi, the City of Light. For over 2500 years this city not only attracted pilgrims but also seekers of truth all over India. Diana Eck (1982) says, “Sages, such as the Buddha, Mahavira, and Shankara, have come here to teach” (4). Religious seekers, ascetics, and yogis found this to be an ideal place for their retreats and hermitages. According to Eck, Chinese traveler Hien Tsiang also noted in his seventh century journal about the streams of pure and clear water flowing through the city. Eck describes Varanasi as an inviting sacred precinct with an abundant forest and temples and ashrams on the banks of lake and stream.

She says, “The fact that there was so much water certainly had contributed to its popularity as a religious center” (50). Thus, great sages, yogis, and ascetics assembled in Varanasi.

Sages came to expound their philosophical teachings while yogis and ascetics made their hermitages for meditation and other practices. Young enthusiastic men flocked to Varanasi to study the Vedas with the city’s great sages. The sages and seekers of this period were not primarily brahmins. There were others, called shramanas (ascetics), who a taught new introspective, non-brahminical wisdom. The period witnessed a variety of new 13

philosophical viewpoints develop. For instance, Upanishadic sages claimed that reality cannot be apprehended by our senses, while Lokayatas contended that reality can be precisely apprehended. Varanasi became the center of this diverse developing thought. Eck says, “By the sixth century BCE Varanasi was more than a city; it was the sacred kshetra, the field that stretched out to the adjacent land of pools and groves where seekers and sages had their retreats” (55).

Varanasi was also a key city for Buddhist thought. One of the most famous seekers of the time was Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha, 6th Century B.C.E), born a prince in a small kingdom in northern India. After his enlightenment, he gave his first sermon at Sarnath (Deer Park), a suburb of Varanasi. His first teaching was on the Four Noble Truths and then later he taught Eightfold Noble Path. Eck quotes Moti Chandra, a historian, “Varanasi at this time was so celebrated that it was only suitable for the Buddha to teach a new way and turn the wheel of the law there” (56). During Buddha’s long career, he often returned to Varanasi’s Deer Park with his disciples for the rainy season retreat. As a matter of fact, for 1500 years, Varanasi continued to be an active monastic center of Buddhism. In the fourth century BCE the Buddhist Emperor Ashoka built a great stupa there to mark the city as a sacred Buddhist pilgrimage site. When Huen Tsang visited Varanasi in the seventh century, he reported that there were some thirty monasteries and 3000 monks.

In addition to the Buddha, Varanasi also attracted sages of the other great heterodox community, the Jainas. The Jaina spiritual leaders were called Jinas, Victorious Ones, or tirthankaras, the ford-markers. According to Jaina, the seventh Jina, Suparshva, was born in Varanasi. Parshvanarha, the twenty-third Jina is also said to have been born in 14

Varanasi. Jina Mahavira, a contemporary of the Buddha, also visited Varanasi during his forty-two years of promulgating Jaina teachings. Since the time of Jina Parshvanatha to the present, the Jainas have continued to have a presence in Varanasi and regard it as their own sacred tirthas. Jaina scholar Jina Prabha asks in his book Vividha Tirtha Kalpa, “Who does not love the city of Kashi, shining with the waters of the Ganges and with the birthplace of two Jinas?” (58).

The philosophical speculations and the disciplines of Mahavira and the Buddha also produced the philosophers and seers whose teachings and ideas were rooted in the Upanishads. Though these seers were orthodox, in the sense that they took the Vedas as authoritative, their focus was not on the Vedic rituals. Rather they focused on philosophical questions such as, “What is the cause? What is Brahman? Whence are we born?”

It was the search and the penetration into the nature of the things that gave rise to the philosophies of the Upanishads and the disciplines of yoga that resulted in different schools of the philosophical thought. The emergence of different schools and their darśanas (view points) also conveyed the message that every philosophy is a means to understand the truth but from diverse angles. The Samkhya and Yoga, the Mimamsa and Vedanta, the Nayaya and Vaisheshika–all emerged as orthodox darśanas. All these schools lay out diverse theories of causality and diverse means to know the truth; still they all have one objective: liberation, moksa. Eck says, “Through the centuries, the darśanas emerged and refined their views in debate and dialogue with one another” (59). Besides the rise of different darśanas, bhakti movement was another development during Shankara’s time. J.G. Suthren Hirst (2005) says, “Very importantly for our understanding 15

of Shankara’s background, the period was one in which devotion to Siva and Visnu was rising, with the massive growth of Tamil bhakti traditions” (26). As these different schools started arising, the competition among these schools also got fierce for the royal benefaction and economic security. This was one of the reasons for the social and religious unrest at the time of Shankara.

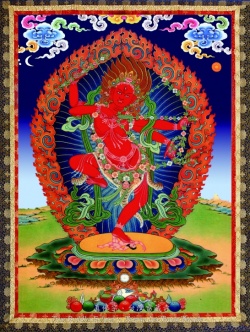

In addition to all these philosophical and devotional movements by the eight century, one of the most vibrant movements of the age was Tantra. Tantra is regarded as secret and its teaching and practices are only to be revealed by the guru with the appropriate initiation. The tantric texts are seen as a revelation from Lord Siva and superior to the Veda. According to Flood, the tantric traditions tend to be sectarian as they always believe that their own revelations are superior to any other traditions. Tantra is also well-known for its erotic and antinomian elements, such as ritual sex and the consumption of alcohol and meat offered to deities.

Eck claims that this movement was very evident in Varanasi according to the inscription by a pilgrim named Pantah (8th century CE.). He describes the image of the goddess Bhavani, called Chandi, as horrific, wearing a necklace of skulls. Creeping snakes hang from her throat, diced is meat stuck to the blade of her axe, she is dancing playfully, and her eyes are rolling. Pantah even established a temple for this goddess.

Shankara grew up in this age of historical and religious flux. The followers of these schools sought to prove their orthodoxy by interpreting the Vedanta sutras in accordance with their own tenets, showing their claim to be based on, and evolved from, ancient tradition. Shankara felt that these thinkers were neglecting the central teaching of the scriptures by performing rituals, engaging in devotional practices, or performing ascetic 16

practice to achieve moksa (liberation). According to Shankara, says Dasgupta, all these were degraded practices and could not bring about liberation. Dasgupta says, “No meditation or worship or action of any kind (as embraced by others) was required but one reached absolute wisdom and emancipation when the truth dawned on him that the Brahman or self was the ultimate reality. The teachings of the other parts of the Vedas, the karmakanda (those dealing with the injunction relating to the performance of duties and action), were intended for the inferior types of aspirants” (436). Dasgupta goes on to say that throughout the commentary on the Bhagavadgita, Shankara tries to demonstrate that those who should follow the injunctions of the Veda and perform Vedic deeds, such as sacrifice etc, belonged to a lower order.

Another cause of religious unrest and instability developed because individual feudal kings embraced and favored certain form of religion. According to Eck, Varanasi saw rulers embracing Buddhism, beginning with the Emperor Ashoka, while the Shunga kings, in the first and second centuries BCE, supported Brahmanism. A little later, (1st century CE), Kanishka of Kushana empire who ruled over Varanasi became a patron of the Buddhist tradition. After the fall of Kushana Empire, Varanasi came under the control of kings who favored the Hindu tradition. The Bhara Shivas, a local dynasty, followed by the great Gupta dynasty, ushered in an age of Hindu revivalism, after centuries of Buddhist domination. Hirst says, “This was important in a context where competition for royal patronage for temple-building and economic security was fierce” (27). By the end of the Gupta rule in the sixth century, Hirst continues, all kinds of sectarian devotional movements, such as Buddhist, Vaishnava, Shaiva, Shakti and so forth, prospered in Varanasi. However, Varanasi remained under the control of different 17

Hindu Kingdoms in North India until the establishment of Delhi Sultanate and Muslim control at the beginning of the thirteen century. These centuries saw Varanasi established as the stronghold of brahminical Hinduism. The theistic Hindu tradition, as a result, continued to grow. At the time of spiritual strife and unrest, as Mahadevan puts, Shankara was preaching, debating, and gathering disciples into the Advaita lineage, the lineage he acquired from Govindapada and Gaudapada.

II.

Gaudapada’s Influence on Shankara

It is traditionally said that Govindapada and Gaudapada were Shankara’s teachers. Govindapada was his immediate teacher, while Gaudapada was his teacher’s teacher. However, as Isayeva notes, “depending on the degree of closeness to their systems, as well as on his personal esteem, Shankara addresses his direct or indirect teachers differently and bestows his praise on them differently” (33). She also says that Shankara respectfully would refer to Gaudapada as param-guru (grand-teacher) and also as the teacher, who knew the tradition of the Vedanta, while very little of significance was said about his immediate guru, Govindapada. Mudgal says, “He held him (Gaudapada) in high regard, perhaps respecting him more than his direct teacher [Govindapada]” (1). In addition, Gaudapada was the pioneer of Advaita Vedanta, whereas Govindapada only transmitted to Shankara the teachings expounded by Gaudapada. Spiritually, Shankara might have felt much closer and indebted to Gaudapada. One very obvious reason for Gaudapada’s dynamic influence was their gurushishya (teacher-disciple) relationship. A guru-shishya parampara (lineage) is a spiritual relationship based on the transmission of teachings from a guru (teacher), to a shishya (disciple). Generally, in this tradition, guru is significant in transmitting knowledge to his shishya through a strong guru-shishya relationship. Through deep respect, commitment, devotion and obedience, the student eventually masters the knowledge that the guru embodies. Shankara illustrates in his “Crest-Jewel of Discrimination” how the guru is upheld by his disciple. He says:

Let the seeker approach the master with reverent devotion. 19

Then, when he has pleased him by his humility, love and service, Let him ask whatever may be known about the Atman

O Master, friend of all devotees, I bow down before you. O boundless compassion, I have fallen into the sea of the world- Save me with those steadfast eyes which shed grace,

Like nectar, never ending.

Thus anyone seeking to study, for example, a Vedanta or tantra, should learn from a guru. The guru-shishya relationship has evolved as an essential element of the Indian philosophical tradition since the oral traditions of the Upanishads (2000 BCE). The term Upanishad derives from the Sanskrit words upa (near), ni (down) and sad (to sit) — "sitting down near," thus referring to a spiritual teacher giving instruction to a seated student in the guru-shishya tradition. An example of this dynamic can be found embodied in the relationship between Krishna and Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita or between Rama and Hanuman in the Ramayana.

The knowledge communicated from a guru to his shishya by word of mouth over generations brings about the traditional guru-shishya parampara, or lineage.

In Shankara’s words, says Isayeva, a true teacher’s tradition is called “sampradaya” (“transmission granting;” that is, a handing over of an established doctrine from teacher to teacher). For Shankara the knowledge acquired in this tradition is more significant than any other kind of learning or erudition. Isayeva quotes Shankara, “A conceited knower might say: ‘I shall reveal the essence of samsara/bonds/ and the essence of liberation, /I shall reveal/ the essence of the sastras’ but he is himself confused and is stupefying others since he rejected the teacher’s tradition of deliberation on the essence of the 20

sastras and came to the refutation of scripture and to mental construction opposing scripture” (32). Traditionally, the ultimate lineage of one’s guru goes back to one highest deity. As Flood says, each guru is seen to be within a line of gurus, or parampara, originating possibly from a deity. This line of succession authenticates the tradition and teachings.

Thus, owing to the guru-shishya tradition, and most importantly to Shankara’s expressed personal admiration, respect, and reverence for Gaudapada, there is no doubt in people’s mind about the influence of Gaudapada on Shankara. Dasgupta says, “Shankara himself makes the confession that the absolutist (Advaita) creed was recovered from the Vedas by Gaudapada. Thus at the conclusion of his commentary on Guadapada’s karika, he says, “he adores by falling at the feet of that great guru (teacher) that adored of his adored, who on finding all the people sinking in the ocean made dreadful by the crocodiles of rebirth, out of kindness of all people, by churning the great ocean of the Veda by his great churning rod of wisdom recovered what lay deep in the heart of the Veda and is hardly attainable even by the immortal god!” (422). Shankara’s guru Gaudapada is historically believed to have been greatly influenced by Buddhism, especially by Vijnanavada (mind only school) and Sunyavada (Madhyamika or Middle Way) schools. These two streams of Buddhism were well established and were flourishing in India before and during Gaudapada’s lifetime. Mudgal says that at the time “Buddhism was politically respected, favored by scholars, and dogmatically accepted by the common man” (133). In addition, he notes that Buddhist teachers like Nagarjuna, Asanga (310-390 CE), and Vasubandhu (420-500 CE) 21

and their teachings already had great influence over the minds of intellectuals. He says, “It is almost impossible to escape their influence” (133). Historically, after the Buddha passed away (500 BCE), disagreement over monastic discipline arose between different monasteries “often due to the variant development of different geographical separated communities, rather than from actual disagreement” (Harvey 1990: 74). According to Peter Harvey, different schools of Buddhism thus developed from the different interpretations of certain rules and aspects of dharma. Initially, eighteen schools of Buddhism emerged at the time of the great Indian King Ashoka in the first century B.C.E. In addition, he says that Ashoka’s espousal of Buddhism helped the religion to become a popular religion and also spread throughout Asia.

According to Harvey, Mahayana Buddhism, which arose some time between 150 BCE and 100 CE, was not associated with any particular individual, nor was it linked directly to any of the eighteen schools mentioned above. He believes that it arose “as the culmination of various earlier developments” (89). However, Dasgupta in his History of Indian Philosophy says Mahayana evolved from the Mahasanghikas, one of the early eighteen schools of Buddhism. He says, “It is difficult to say precisely at what time Mahayanism took its rise. But there is reason to think that as the Mahasanghikas separated themselves from the Theravadins probably some time in 400 BCE and split themselves up into eight different schools, those elements of thoughts and ideas which in later days came to be labeled as Mahayana” (125). Nevertheless, others contend that it is because when Mahayana first emerged, it resembled Mahasanghika in several areas of doctrinal interpretation. For instance, Mahayana resembles Mahasanghika in believing 22

that the lay person is also capable of becoming an arhat (foe-destroyer). In contrast to Theravada, they both encourage lay people in the practice. Unlike Theravadism they both believed the presence of Buddha exists not only in humans but also in the transcendental state of being. Thus both share the view of Buddha as a supernatural being who assumed a transformation body (nirmana-kaya) and later born as historical Buddha. Harvey mentions about the three main ingredients of Mahayana movements. One of them was “a new cosmology arising from visualization practices devoutly directed at the Buddha as a glorified, transcendent being” (90).

The Mahayana teachings became popular after the new millennium and continued to spread throughout Asia in the first century C.E. Over the following centuries, the teachings became a very strong presence in countries throughout Asia, including Tibet. As Mahayana developed, two schools of thought emerged, the Madhyamika (the Middle Way) and the Yogacara (the Mind Only School). The former developed out of the teachings of Nagarjuna, a Buddhist sage from the south of India. His most important work - the Mulamadhyamika-karika (Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way) - aimed to show the truth of the emptiness or sunyata by argument. His basic argument is that all things are conditioned and therefore cannot be said to have an inherent nature, an undying essence. The world we perceive is made up of ever-changing dharmas, mental and physical constituents that only have significance in the way that they relate to each other. Yogacara or the Mind Only School of Mahayana Buddhism was founded in the 4th century CE by two brothers, Asanga and Vasubandhu. This school argued that the world as we perceive it is a creation of the mind. As individuals we therefore create imaginary worlds that are mistaken for real existence.

According to Hacker (1952) the profound influences of Buddhism on Gaudapada were from the Lankavatara-sutra and the writings of Nagarjuna and Vasubandhu. Thus, some scholars are of the opinion that he was a “crypto-Buddhist.” Isayeva says, “His work mandukya-karika was undoubtedly composed under the direct impact of Buddhist ideas” (10). She continues, “And it was from Buddhism that Gaudapada borrowed the notion of the illusiveness of manifold world activities and perceptions that being cut short and exhausted in the moment of true seeing” (52). Scholars also charge that Gaudapada’s mandukya-karika reveals notable Buddhist influence on his formulation of non-dual Advaita, especially in the last chapter.

Consequently, scholars argue that due to Gaudapada’s influence, Shankara incorporated Buddhist ideas and images in his writings, most importantly the concept of maya. Shankara’s concept of mayavada is one of the most complex and important elements in his thought. Mudgal claims that the theory of maya is first introduced into Vedanta by Gaudapada. He says, “maya doctrine as the theory of illusion is not be found, nor any suggestions of that doctrine are to be found, either in the Vedas or in the Upanishads, or in the Gita” (69).

These are indeed compelling reasons to see the influence of Buddhism on Shankara. First, as mentioned in previous section, Buddhism was well established and flourishing before Shankara was even born. Secondly, there is no disagreement among the scholars about the influence of Buddhism on his guru, Gaudapada, who had tremendous impact on Shankara’s life through their guru-shiksha relationship. The influence of Buddhism, through Gaudapada, especially in his philosophy of Advaita Vedanta was the actual basis for the criticism of Shankara being a crypto-Buddhist. 24

Shankara’s critics argue that most of his works contain Buddhist (Mahayana) elements and very little of original thought. For instance, Dasgupta argues, “Much of the dialectics of the reasoning of Shankara and of his followers and the whole doctrine of maya and the fourfold classification of existence, and the theory of Brahman as the ultimate reality and ground, were anticipated by the idealist Buddhist, and looked at from that point of view there would be very little which could be regarded as original in Shankara” (195). Sharma (1952) has a similar contention. He argues that the similarities between these two schools cannot be denied on any ground since they are so many and strong while any differences between them are few in number and insignificant. Thus, the only difference between the two would be, “a matter of degree and emphasis and not a matter of difference in kind” (Mudgal, 9). Taken together, these arguments suggest that Shankara’s Advaita philosophy is virtually indistinguishable from the sunyata of Nagarjuna. A thorough analysis of Shankara’s philosophy becomes crucial for determining the validity of these contentions. The following section, therefore, will examine Shankara’s concepts of Brahman, Atman, moksa, avidya, and maya respectively, the key points of similarity. 25

III.

Shankara’s philosophy

Brahman

The main tenet of Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta system is that there is nothing but the non-dual supreme reality, without any qualities or characteristics. This supreme reality is Brahman. Shankara says, “Brahman alone is real. There is no one but He. When He is known as the supreme reality there is no other existence but Brahman” (69). Mudgal describes Shankara’s Brahman as the reality that transcends the duality of subject and object, knower and known.

He says, “It is what it is. It does not become, for it just IS. It is Perfect Being, the Full, the grown. Therefore it IS” (5). Brahman is the truth devoid of any attributes. According to Mudgal, Shankara explains this further in his story concerning Kauntey and Radheya. In Shankara’s advaita system, Brahman, the ultimate Reality, is not something which has to be attained newly. Rather, it is always there, except one is not aware of its existence due to the power of ignorance.

To illustrate this, he says, “Karna was born Kauntey; however, he believed he was a Radheya; for all that, he was not a Radheya; when he was told that he was really Kaunteya, he did not become Kaunteya, which he always was, but of which unfortunately he was ignorant. Yet it was a revelation which one has through knowledge” (14).

Shankara, says Isayeva, also uses other metaphors, such as the metaphor of invincible light in an empty space to illustrate the attributeless Brahman. Shankara says the light is simply invisible not because of its non-existence, but because there is no object to illuminate. Likewise, nirguna Brahman is also not perceived because it transcends all attributes and relations. 26

As a result, Shankara warns against any rational conception or description of Brahman, for it limits the unlimited Brahman. He emphasizes that any idea that Brahman has attributes is superimposed by our ignorance and should be repudiated. He says, “Caste, creed family and lineage do not exist in Brahman. Brahman has neither name nor form; it transcends merit and demerit; it is beyond time, space and the objects of senseexperience” (75). It is, therefore, best described via negativa. In Shankara and Indian Philosophy, Isayeva says, “There is no other and no better definition of Brahman than Neti, Neti- not this, not this” (116). However, she says that this is not a denial of any positive attributes of Brahman. It is instead a means to turn the minds of aspirants from the worldly concern towards the understanding of the reality. Cronk asserts that the appearance of Brahman with attributes is “only a view based on the human need to understand the true nature of Brahman” (33). In addition, A.C. Das (1952) reports, “Hence, the neti-neti (not this, not this) method to which the Advaitists have recourse does not in any way indicate that it is just a void. On the contrary, the method brings out that Brahman, being the ultimate reality, is unique and as such cannot be determined in thought, which involves comparison and analysis” (145). For Shankara, Brahman “is unchangeable, infinite, and imperishable” (76). According to Swami Prabhananda and Christopher Isherwood (1978), Shankara’s concept of reality is that which neither changes nor ceases to exist. Anything that endures temporarily is not an absolute reality. Prabhananda and Isherwood claim, “The world is subject to modification and therefore, by Shankara’s definition, it is “not real” (8). Thus, by definition, any experiences during the states of waking are not real as they are bound to change.

Only deep consciousness is real in Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta, note Prabhananda and Isherwood. They say, “There is only one thing that never leaves us–the deep consciousness. This alone is the constant feature of all experience. And this consciousness is the real, absolute Self” (8). According to them, this consciousness is present during dreamless sleep, when characteristics and attributes like the sense of “I” or “Self” have temporarily ceased. Shankara argues that each person’s soul in the deep sleep (susupti) comes closer to unity with Brahman, though temporarily. In Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta, this pure consciousness, which is present in all being, is Brahman, but it has temporarily forgotten its identity as Brahman. Thus, the goal of a person is to realize the innermost self within one’s own being by removing all the temporary characteristics and attributes.

This description, however, is not meant to identify pure consciousness as the characteristics or an attribute of Brahman (nirguna). Shankara, as mentioned earlier, strongly rejects any attributes on Brahman. Instead pure consciousness, in Shankara’s view, is one with Brahman. Brahman does not possess pure consciousness nor is consciousness the nature of Brahman. Pure consciousness, in fact, does not belong to any individual.

It is inconceivable and indescribable, like Brahman. According to Cronk, Shankara’s logic for equating pure consciousness with Brahman is as follows: “If all differences and distinctions are unreal and if Being and consciousness are both real, it follows that there are no differences or distinction between Being and consciousness. They must be one and the same. Therefore, consciousness itself is Being-that which is. It also follows that Being is consciousness. So the essential nature of Brahman-the sole reality-is consciousness” (76). Thus in Advaita Vedanta, pure consciousness is eternal, 28

one with the Brahman, and is inherently present in everyone. It is Brahman, free from all names, qualities, and so forth.

The fundamental question being posed to Shankara by his critics is about the attributeless Brahman and its relationship with the apparent world. In what sense is Brahman the creator of this universe and how does one explain the world of differences? On what account does the multitude of changing world relate to unchanging attributeless Brahman? As a matter of fact, Shankara’s description of Brahman’s relationship with the manifest world is unique from other Hindu orthodox schools. According to Shankara, the manifold world is a mere appearance of Brahman due to avidya (ignorance) and maya (illusion).

Mahadevan explains this unique concept of Shankara by saying, “there is no real causation; the world is but an illusory appearances in Brahman, even as the snake is in the rope” (59). Therefore, according to Shankara, there is no real creation. However, Mahadevan also says, “When viewed in relation to the empirical world and the empirical souls…Brahman appears as God, the cause of the world” (59). Thus in the Advaita system Brahman has two characteristics, nirguna (attributeless) and saguna (with attribute). Saguna (with attributes) Brahman is the personal God, all-good, all powerful, the creator of the world and so forth.

To illustrate, Shankara compares saguna Brahman to an infinite ocean. Like the formless ocean water, he says, which freezes and takes the form of ice, similarly Brahman (saguna) also appears to devotees in response to their intense love and devotion. But ultimately, he says, the icy form melts away as the knowledge of sun rises. Thus, reference is made to saguna Brahman when Brahman is described as the cause of this multiple world.

Cronk says, “To speak of Brahman as the cause of the world presupposes a duality of Brahman and world, and such dualistic thing 29

is grounded on ignorance of the true nature of Brahman and Atman” (33). It is only in the dualistic thought, perception of the manifest world as real and separate entity, the possibility of Brahman (saguna) as the cause of the apparent world. In ultimate reality, there is nothing but the unity of Atman-Brahman. The real Brahman (nirguna) is always without characteristics, without action or change.

The concept of Brahman without any attributes, nirguna, is a unique view of Advaita Vedanta. No Hindu orthodox school, except Advaita Vedanta, advocates that Brahman is devoid of all the attributes. This unique view of Brahman as attributeless, impersonal and so forth has incited other orthodox schools to criticize Shankara as crypto-Buddhist. They contend that this view is no different from Nagarjuna’s concept of sunyata.

Atman

The ultimate unity of Atman-Brahman mentioned above is another unique view of Shankara.

However, this is not a combination of two different realities; rather, Atman (True Self) and Brahman are identical.

Pure consciousness, which is equated as one with Brahman and inherently present in everyone, is Atman (True Self), according to Shankara.

Isayeva says, “Atman in Advaita is pure consciousness, being one and only one it has nothing by way of parts or attributes” (115).

For Shankara this True Self (Atman) is not different from Brahman but is Brahman itself.

It does not ultimately dissolve or disappear when Brahman is realized.

Atman, according to Shankara, is unified, so it is a misconception to believe that there are many.

Shankara compares this misconception with the analogy of the moon appearing on the surface of water.

He says, just as the moon appears as many on the surface of water covered with bubbles, likewise the one 30

Atman also tends to appear as many in our bodies because of avidya (ignorance), adyasa (superimposition) and maya (illusion).

For instance he argues, when a person thinks "I am blind,” "I am happy,”

"I am fat" etc., one identifies with one’s body, perceptions, feelings and so forth.

This, Shankara says, is ego. The sense of an individual self (jiva) with a body and senses is superimposed by maya (illusion).

Therefore, each jiva feels as if he possesses his own, unique and distinct Atman.

Nevertheless, the concept of jiva is true only in the pragmatic level. In the transcendental level, only the one Atman, equal to Brahman, is true. It is free and beyond all the attributes.

This concept of Atman as commensurate with Brahman is what separates Shankara’s system from others as nondualism. In this system, upon realization of Brahman, one’s Atman merges with Brahman and any sense of individuality thereby disappears.

By contrast, the other orthodox schools equate the person’s soul with Atman as well as value his or her individual identity; thus, the Advaita idea of Atman becoming one with Brahman ultimately is not their ideal or ultimate goal.

Moksa

In Shankara’s system, the ultimate unity of Atman-Brahman is the ultimate goal of liberation (moksa). Moksa is achieved when one realizes the direct knowledge of Brahman. Shankara says:

Know the Atman, transcend all sorrows, and reach the fountain of joy.

Be illumined by this knowledge, and you have nothing to fear. If you wish to find liberation, there is no other way of breaking the bonds of rebirth. What can break the bondage and misery of this world? The knowledge that the Atman is Brahman.

Then it is that you realize Him who is one without a second, and who is the absolute bliss. Realize Brahman, and there will be no more returning to this world-the home of all sorrows. You must realize absolutely that the Atman is Brahman. (69)

Similarly, Isayevea asserts that Shankara’s notion of “liberation from this cosmic illusion” is to “return to Brahman” (3). Swami and Isherwood say, “Certainly, the goal is to realize and ultimately become one with Brahman” (29).

This realization of an individual soul ultimately merging with Brahman is a unique trait of Advaita Vedantic School.

The merging of Atman (individual soul) with Brahman uproots the sense of duality and liberates the individual from the cycle of samsaric transmigrations. In that state, one experiences Brahman or Absolute Being in the most intimate and non-separable way.

This is because the nirguna aspect of Brahman is dissociated from all qualities and attributes.

Mudgal feels that Shankara ultimately believes that “there is neither the self-awareness nor the awareness of the Self, as it is awareness itself and as so experienced it is “Silence” (7). In this way, the seer loses all his individuality and specific characters when he ultimately merges with Brahman.

One simile used in the Mundaka Upanishad, according to Dasgupta, is the comparison of the illumined seer to a river.

He says, “Just as all rivers flow into the ocean and lose their names and forms, so does the seer lose his name and forms, when he becomes free, when he loses himself in the true freedom of this great truth (38).

However, Dasgupta clarifies that this is not due to the disconnection of self with the world but due to the failure of worldly appearance as the ultimate and highest truth.

According to him, all our perceptions of multiplicity of the external world and self are 32

pure illusion and deceptive.

The moment one realizes the ultimate truth concerning Brahman, all external appearances and its deceptions dissolve naturally and the ultimate truth, Brahman, becomes very apparent.

Nevertheless, for Shankara, this merging of Atman and Brahman cannot be achieved through moral and religious acts, or through worship of a personified God. He also says that one cannot achieve this goal through the intellectual effort or the accumulating various intellectual data.

For instance, Hirst exclaims in his book, Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta: A way of Teaching, that “Brahman may be known through reading of the scriptures, but it cannot be perceived by the senses. It cannot be expressed or described, because it transcends names, classifications, or characterizations.

It cannot be known by reasoning, but its existence may be apprehended intuitively” (39). However, Isayeva indicates that Shankara accepts these means only to assist one in moving towards Brahman, but not as the actual realization.

For such a spiritual quest, giving up desire for worldly pleasure and resorting to the meditation on the meaning of Brahman is also required. Seeking a qualified teacher also becomes indispensable for the highest illumination.

These means help to discriminate Atman from non-atman, which in turn helps to burn away ignorance, avidya.

Shankara believes that liberation (moksa) can be realized when one is still alive. Liberation attained in this life is called jivanmukti while liberation attained after death is videhamukti.

Mudgal says, “When one becomes jivanmukti this world of senses has ceased to exist although he lives and moves in it” (157). However, the body of a realized seer is still subjected to suffering and pain even when he has eliminated his ego. He escapes from this only when he leaves behind his body at the time of death. The final 33

disappearance of all identification comes when he dies and leaves behind his body.

This is the ultimate realm of silence, from where he never returns. Isayeva says, “In Advaita, the ultimate liberation is placed beyond the causal chain of phenomena” (157).

Thus, for Shankara, Brahman is not something to be attained or achieved, but rather to be realized. In short, in the steps to liberation, the first is to have complete detachment from all things which are non-eternal.

Then the practice of tranquility, self-control, and forbearance are implemented. This is followed by sacrificing all actions, which is usually done from personal, selfish desire. Then one must hear the truth of the Atman, reflect on it, and meditate upon it. Eventually, Prabhavananda and Isherwood claim, one is able to realize the ultimate truth, Brahman, in which the sense of duality is dissolved and the infinite unitary consciousness alone remains.

Moksa is not, according to Shankara, a perfection to be achieved; it is rather the essential reality of one's own self to be realized through destruction of the ignorance that conceals it. Shankara’s notion of jivanmukti and vedhamukti is not unique to his Advaita system. Other orthodox schools like Mimamsa also believe in the attainment of liberation (jivanmukti) in this life time.

Avidya

Although the attainment of Moksa or the realization of Brahman is within and inwardly experienced, one is still entangled in endless and vicious cycle of death and rebirth, with pain, suffering, and confusion. Shankara attributes these to avidya (ignorance) and to maya (the power to deceive). He says, “Because you are associated with ignorance, the supreme Atman with you appears to be in bondage to the non-Atman.

This is the sole cause of the cycle of birth and deaths” (39). 34

According to Shankara, there is a disposition in human nature to misidentify between Self and not-Self, between subject and object. For instance, Cronk says, “There is a natural human tendency, rooted in ignorance, not to distinguish clearly between subject and object and superimpose upon each other the characteristic nature and attributes of the other” (26). Mahadevan makes similar remarks regarding ignorance. He says that we mistakenly identify that the self is the subject of transmigration and that the world in which this happens is real. He concludes that “all these notions are due to ignorance” (66).

To illustrate this concept, Shankara employs the ‘snake in the rope’ analogy as a demonstration of avidya and its superimposition. This analogy suggests that the world is like falsely seeing a snake in the place of what actually is a harmless striped rope.

However, when this harmless striped rope is mistaken for a poisonous snake, an observer takes fright. In this manner, says Shankara, the manifest world is also perceived, when in reality, the manifest world is purely illusion (maya).

The snake which appears on the rope, in actuality, is not different from the rope, nor is it the same as the rope. Its appearance depends upon the rope and vanishes with the rope. However, the appearance and disappearance of the snake does not affect the nature of the rope.

The rope is the ground for seeing the snake, as Brahman is for the world of plurality. The world, like the snake, is an illicit projection, a super-imposition due to ignorance. The snake is an error; it is not real as rope, nor unreal, it is somehow there. Shankara says, “The world is not caused, but not uncaused, but not both and not neither; it is indeterminate; it is somehow there” (9).

In the same manner, says Isayeva, ordinary people are not able to understand that all attributes are falsely projected on the Atman. Not being able to separate the body and its attributes from the Atman, one superimposes these as “I” and “Mine.” This identity is falsely constructed by the ego, and thus is not a real attribute of the True Self (Atman). Thus Hirst says that one is mixing up body with self, or even senses and feelings with the self.

He warns that as long as these misconceptions are there, liberation from the samsaric rebirth is not possible. Realizing Brahman is a person’s ultimate goal, avidya (ignorance) must be removed. Misconception is then replaced by knowledge and the appearance world of name and form disappears like the imagery of a dream. In Shankara’s system, ignorance (avidya) is the main obstacle for the direct knowledge of Brahman, the Ultimate Reality. In other words, removal of ignorance leads to the realization of one’s identity with Brahman. Other orthodox Hindu schools disagree with this idea and also with the idea that the manifest world is caused through ignorance.

Maya

According to Shankara, this manifold world appearance is caused by maya. Shankara says, “It is she who gives birth to the whole universe” (Jewel-Heart Discrimination, 49). It is the inherent power or potency of Brahman. Maya obscures reality and projects the world of plurality. However, maya is neither real nor un-real. Maya is absolutely dependent on and inseparable from Brahman. Maya is non-different from Brahman but Brahman is never affected by its profanity, just like the illusionist is not affected by his own illusion. Maya is anadi (beginningless), indescribable, and indefinable as well. Thus in the Advaita Vedanta system, Dasgupta says, “The relation of maya and Brahman is unique and is called tadatmaya” (172). Maya’s apparent existence 36

only disappears when the ultimate truth, Brahman, is realized. Shankara’s concept of maya (illusion) was highly criticized. Scholars argue that Shankara is indebted to the Buddhists for his concept of maya. Although the word maya occurs in Bhagavadgita, scholars argue that Shankara’s theory of maya is nowhere to be found in Vedas or in Upanishads. Instead, they charge that it is a doctrine first initiated in Vedanta system by Shankara’s guru, Gaudapada. Mudgal says, “The doctrine of maya as understood by Shankara was first introduced in the Vedanta by Gaudapada karika” (69). After having analyzed all the key concepts of Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta system, the following sections will assess each criticism to see if these concepts are original or borrowed from other traditions.

IV.

Critiquing Shankara’s Philosophy

In light of Shankara’s philosophical views as presented in his Advaita system, critics like Sharma, Dasgupta, Mudgal, Smart, and others have contended that Shankara is a crypto-Buddhist. These arguments are most clearly laid out by Mudgal in his book, Advaita of Shankara- A Reappraisal (1975).

My particular attention to Mudgal is not because I am responding to him particularly or more than the other critics, but because among the scholars who have examined this issue, Mudgal is the one who gives the most systematic and point-by-point comparative analysis of Sankara’s system of Advaita Vedanta and the Mahayana Buddhism of Nagarjuna, while the comments made by other scholars are less comprehensive and more eclectic. By examining his work and responding to it, I am able to cover the range of issues addressed by the other scholars as well.

However, it should be clear that I am responding to all these scholars and not Mudgal alone.

In this book Mudgal interprets the ultimate reality of both the Mahayana school of Nagarjuna and the Advaita system of Shankara as transcendental. He says, “The tattva (that-ness) of Nagarjuna and the Brahman of Shankara are both transcendental to thought” (176). His claim is based on the fact that both schools accept their ultimate truth as non-dual, ineffable, trans-empirical, beyond thought, or trans-relational. Hence, the ultimate truth, he continues, is not an object of knowledge. He says, “It is not knowable as an object; for all knowability is knowability as an object, therefore, the ultimate cannot be conceived or determined in thought” (176). It is considered as unspeakable or indescribable hence best describe via negativa.

In addition, Mudgal contends that the characterization of Ultimate Reality, Brahman, as bliss in Shankara’s Advaita system is very similar to Nagarjuna’s concept of sunyata. For example, he says that the fundamental belief of Mahayana Buddhism is that all is suffering, change, and substanceless. Therefore, the practice in Mahayana Buddhism is focused on the attainment of a state free from change and sorrow.

According to Nagarjuna, says Mudgal, sunya transcends all change, misery, and sorrow, the characteristics of the empirical world of things. “This Absolute,” says Mudgal, “even though Nagarjuna has not said in so many words, is, by the very nature of Nagarjuna’s dialectic, Bliss” (178).

Another important affinity between Mahayana Buddhism and Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta system is the notion of tathagata-garbha and Atman. Well-known tathagatagarbha texts, like Tathatagata-garbha Sutra (200 CE-250 CE) and Srimala-devi Simhanada Sutra (250 CE-350 CE) describe tathagata-garbha as pure consciousness. According these texts, tathagata-garbha is present in all the beings regardless of whether they are deluded or defiled.

The defilements, says Harvey, “are seen as unsubstantial, unreal, but as imagined by the deluded mind” (116). Tathagata-garbha is present within naturally from the beginingless time. It is unchanging, permanent, and beyond duality. Harvey says, “It is already present, the immaculate true nature to which nothing need be added and from which nothing need be taken” (115). Ultimately, tathagata-garbha is not to be attained, but to be realized by dissolving all the defilements. It is like gold buried under some filth which has simply to be uncovered.

This Buddhist notion of tathagata-garbha is so close to Shankara’s concept of Atman that some Buddhist scholars like Matusmoto Shiro and Hakamaya Noriaki of Soto 39

Zen call into a question of the doctrine of tathagata-garbha. According to Sallie B. King (1997), they argue that Buddha-nature thought is an essentialist philosophy parallel to the monism of Upanishads. In addition, Harvey also says, “Given this description, how then it differ from a permanent Self (Pali atta, Skt atman), which Buddhism had never accepted?” (118).

Next, Mudgal claims, the description of jivas and the manifest world by Shankara’s Advaita system as unreal also has close affinity to nairatmyavada of the Mahayana Buddhists. Mudgal explains that Mahayana accepts pudgala nairatmya (selflessness of person) and dharma nairatmya (non-substantiality of things). In other words, both the individual and things are devoid of any substantial existence. He says, “To the Buddhist, individuality is the ego-substance (jiva)” (179). This notion is very similar to the Vedanta view of Shankara, who rejects jivas as individual, independent and eternal.

According to Shankara, Mudgal says, these attributes are only superimposed on the Absolute because of Avidya (Ignorance). Jivas are, therefore, dependent, limited, relative, and have no absolute existence. Consequently for Shankara, he argues, “They are unreal and even so is the world; it is a case of error” (180). Both the self and the manifest world, in these two systems, therefore, lack substantiality. A similar remark is also made by Smart (1992).

He says, “The effective denial by Shankara of a plurality of selves brings him closer than any one else to the Buddhist viewpoint” (89).

Mudgal also charges that both view jñana and prajña as the means of liberation, limiting the role of karma and bhakti within the empirical world. The terms nirvana, moksa, and mukti used in Mahayana and Advaita both refer to liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth. According to Mudgal, nirvana refers to the realization of the 40

Supreme knowledge, perfect peace and absolute freedom. Here he reiterates his previous analogy by saying that the disappearance of waves is due to the calmness of the ocean, therefore the waves are non-distinct from the ocean. Similarly, “the individual is lost in the absolute beyond recognition” (183) when all the adjuncts of avidya are removed. As a matter of fact,

Mudgal confirms that “the ultimate identification of knowledge with Reality is a characteristic of both the schools” (176). In addition, they both accept, he says, jivan mukti and videha mukti. The first kind of mukti or nirvana, according to both, can be realized when one is still alive, while the other is realized only after the seer leaves his physical body behind when he dies.

Finally, Mudgal likens Shankara’s understanding of maya with the Mahayana’s notion of illusory nature.

He contends that both believe that the world is maya. In other words, this manifest world, which everyone perceives and experience, is illusory.

He says, “It is a creation by the self deluding itself by its avidya” (180).

He refers again to the analogy of waves on the ocean. As the waves on the ocean are not distinct from the ocean, he explains, the world is also non-distinct from the tattva or the Brahman.

He then concludes by saying, “When avidya is overcome or maya is dispelled, what is discovered is Brahman only” (181).

Thus for Mahayana Buddhism and Shankara, the existence of empirical world is only conventional, conditioned, or dependent.

As Smart says “All appearances are illusory, but some are more illusory than others” (89). This feature of illusory nature of all appearances, at the ordinary level, is what Shankara’s system shares with Mahayana Buddhism.

As we have seen in the previous pages, the comparison between Mahayana Buddhism and Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta system are compelling.

They suggest that the 41

fundamental concepts of Advaita of Shankara, like Brahman, Atman, maya, and moksa had already appeared in the Sunyavada system of Mahayana. Therefore, many scholars conclude, Shankara’s doctrine of Advaita does not contain any original thought.

However, there are some subtle but very significant elements of Shankara’s fundamental to his system. These views are not only unique to Shankara, but are some of his fundamental views. These elements are what make Shankara’s Advaita system distinct from other Indian orthodox schools and Buddhism as well.

Mudgal and others are, perhaps, correct to some extent, but that does not justify their conclusion that Shankara is a crypto-Buddhist. The following section will, thus, examine important differences between Shankara and Mahayana thought to see how fundamentally separate Advaita Vedanta is from Sunyavada of Nargarjuna.

V.

Response to Shankara’s Critics

As laid out in the previous section, one of the main reasons Shankara is considered a crypto-Buddhist pertains to his concept of Brahman. Scholars contend that his view parallels the concept of sunyata in Mahayana Buddhism.

This criticism is based on the Advaita Vedanta description of Brahman as the ultimate reality, attributeless, indescribable, and infinite. This characterization of ultimate reality is also very evident in Mahayana’s description of sunyata.

For instance, Harvey notes sunyata of Nagarjuna as the ultimate reality which is not only inconceivable but also inexpressible.

He says, “The ultimate truth, then, is that reality is inconceivable and inexpressible” (102). Harvey also adds that sunyata (the ultimate truth) of Nagarjuna is immutable, unchangeable, undiscriminated, and undifferentiated.

In spite of such similarities, there are some underlying views, regarding Brahman and sunyata, unaddressed by the critics that eventually distinguish them from one another. Shankara’s description of Brahman as permanent and eternal explains it. In Crest Jewel of Discrimination, Shankara says: Brahman is supre me.

He is the reality-the one without a second.

He is pure consciousness, free from any taint.

He is tranquility itself. He has neither beginning nor end. He does not change. He is joy for ever.

He transcends the appearance of the manifold, created by Maya. He is eternal, for ever beyond reach of pain, not to be divided, not to be measured, without form, without name, undifferentiated, immutable. 43

He shines with His own light.

He is everything that can be experienced in this universe.

The illumined seers know Him as the uttermost reality, infinite, absolute, without parts-the pure consciousness. (71) There is also a clear characterization of Brahman as eternal and absolute in his response to the problem of Brahman-world relationship.

Shankara responds to this problem by drawing on Samkya’s (350-450 CE) concept of satkaryavada, with slight variation. Satkaryavada postulates that an effect pre-exists in a cause, and that it is not distinct from its cause.

Samkya believes that the world of evolution is potentially pre-existent in prakrti (nature), before creation; thus, the evolutes are not distinct from prakrti. They evolve out of prakriti and are not different from prakriti.

Drawing on Samkya, Shankara was able to reconcile the seemingly contradictory concepts of an attributeless and absolute Brahman and the manifest world.

Shankara’s analogy of a pot and clay reconciles these two concepts.

He says, “The pot and the earth are not the same, are not different, yet pot is earthen, it depends on earth, the pot as pot is still an earthen pot; the change of earth into the pot is merely a nominal or formal one; the pot being thus nominal or formal is false, and as earth alone it is real” (9).

Another indication of Shankara’s view of Brahman as eternal and absolute is evident in his criticism of Buddhism as a doctrine with flaws. Isayeva notes, “according to Shankara, the greatest defect of this Buddhist doctrine lies in its persistent denial of any permanent subject” (152). Thus, these clearly demonstrate that Shankara’s Brahman is not only the Supreme, Ultimate Reality, but also eternal and absolute.

By contrast, Nagarjuna refutes any view of eternalism or absolutism in his philosophy. Eternalism and absolutism has no place in Nagarjuna’s philosophy of Sunyavada. He advocates the ‘Middle Way’ between externalism and nihilism. According to Nagarjuna, says Harvey, “The nature of dharma (phenomenon) lies between absolute, non-existence, and substantial existence.

This is what Nagarjuna means by the Middle Way” (98). Nagarjuna perceives that all dharma (phenomenon) lack the quality of inherent existence. Anything that appears to exist inherently or independently, according to Nagarjuna, is imputed by one’s ignorance. In reality, all are empty of any inherent existence, including emptiness as well. Thus, all share the same nature, ‘emptiness’.

The Heart Sutra says,

Body is nothing more than emptiness;

emptiness is nothing more than body.

The body is exactly empty,

and emptiness is exactly body.

The other four aspects of human existence -

feeling, thought, will, and consciousness -

are likewise nothing more than emptiness,

and emptiness nothing more than they.

Nagarjuna equates this emptiness with the principle of “dependent arising.”