Shentong madhyamaka and via negativa, a buddhist and a christian approach to the absolute

SHENTONG MADHYAMAKA AND VIA NEGATIVA, A BUDDHIST AND A CHRISTIAN APPROACH TO THE ABSOLUTE; WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON THE TEACHINGS OF THE BLESSED ANGELA OF FOLIGNO (1248/49-1309)

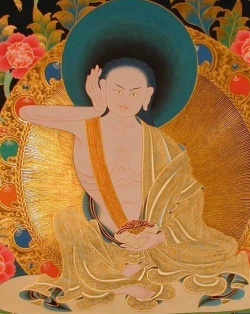

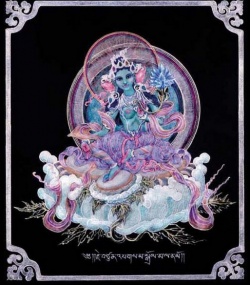

AND THE OMNISCIENT DOLPOPA SHERAB GYALTSEN (1292-1361)

A thesis by

Ellen Rozett

presented to

The Faculty of the

Graduate Theological Union

in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Master of Arts

Berkeley, California

April, 1996

Committee signatures

____________________

Coordinator

____________________

____________________

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vii

FOREWORD viii

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION 1

A. In Search of a Common Language . . . . . . . . . . . 1

B. Perennialists and Constructivists 4

C. The Role of Mystics and their Teachings 16

CHAPTER TWO

THE CHARACTER AND HISTORICAL ROOTS OF VIA NEGATIVA

AND UMA SHENTONG 24

A. What Is Via Negativa? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 B. What Is Shentong Madhyamaka? 31

C. The Development of Via Negativa 42

1. Biblical Roots 42

2. Hellenistic Roots 47

3. Negative-Mystical Theology During the First

500 Years 55

4. The Pseudo-Dionysian Corpus 62

5. Via Negativa in the European Middle Ages 65

D. The Development of Uma Shentong 78

1. In Search of a Positive Nirvana 78

2. Tathagatagarbha and Anatman 86

3. Buddha-gotra, Family of the Buddha, or Arya-

gotra, Noble Family 90

4. Tathagatagarbha and Madhyamaka 93

5. Madhyamaka and Yogacara 99

CHAPTER THREE

THE HISTORICAL AND RELIGIO-CULTURAL SETTING OF

ANGELA AND DOLPOPA 111

A. Angela 111

1. Her Time . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .111

2. Her Religious Inheritance 116

a. Generally Catholic 116

i. The Medieval Women's Movement 116

ii. Union with God 121

iii. Christian Silence 124

b. Her Franciscan Inheritance 129

i. Poverty 129

ii. Penance and Mortification 132

3. Her Person 134

4. Her Position as a Woman 137

5. The Impact of Her Work 145

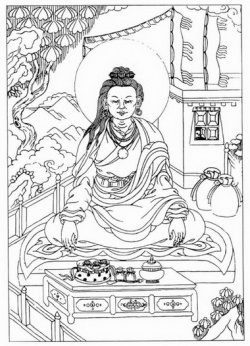

B. Dolpopa 148

1. His Time 148

2. His Religious Inheritance 152

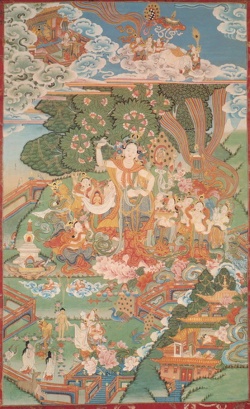

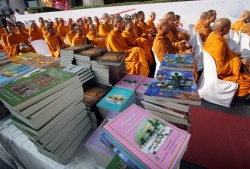

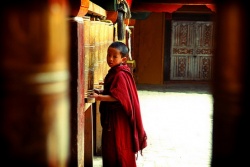

a. Tantra in Tibetan Buddhism 152

b. The Sakya and Jonang Schools 156

c. Buddhist Silence 158

3. His Person 161

4. His Position as an "Omniscient" Male Lineage

Holder 164

5. The Impact of His Work 169

CHAPTER FOUR

THE BASIC TEACHINGS 177

A. The Textual Sources 177

1. Angela's Works 177

2. Dolpopa's Works 188

B. What Angela Says About God 191

1. Identity of Soul and God 196

2. Nothingness of Soul and God 202

3. God is Nothing and Everything 205

4. Is God Inexpressible and Inconceivable? 206

C. What Dolpopa Says About Buddha Nature 209

1. Buddha Nature Is Absolute and the Ultimate

Meaning of Buddha's Teachings 209

2. Buddha Nature Has Inseparable, Uncompounded,

and Inconceivable Qualities 212

3. The Wisdom of Buddha Nature or: Buddha Jnana . .221

4. The Compassion of Buddha Nature or:

Buddha Activity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .224

5. Buddha Nature Is No Other than Form 226

CHAPTER FIVE

COMMONALITIES AND DIFFERENCES BETWEEN DOLPOPA'S BUDDHA

NATURE AND ANGELA'S GOD. 232

A. How Angela's Teachings Match Shentong Philosophy 234

1. The Nothingness of Things 234

2. The No-thing-ness or Inconceivability of the

Absolute 235

3. The Qualities of Buddha Nature and God 241

a. Absolute Wisdom 242

b. Unborn, Uncreated Love 248

B. How Buddhism Could Help Angela 252

C. How Angela Could Resolve Buddhist Debates 256

D. Public Logic Versus Private Intuition 259

E. Angela's Silence and Buddhist Non-conceptuality 262

CHAPTER SIX

CONCLUSION 270

ABBREVIATIONS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .276

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 277

"Qui nescit orare non cognoscit Deum." Gil of Assisi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks be to the One who transcends one and many, for inspiration and sustenance.

Thanks also to Shenpen Hookham, my unknown sister in the Dharma, for her faithful and thorough research without which this thesis would have been impossible.

Thanks to my advisors for tolerating my stubbornness and a thesis they agree with only partially.

Thanks to my parents in law, Kathryn and Walter Rozett. During the last phase of writing, they kept my body from illness or starvation, my mind from insanity, and my thesis from the most grave mistakes and crude language.

A Moroccan once told me that Muslim carpet manufacturers purposefully leave one mistake in their pieces of art in order to acknowledge that only God can do anything perfectly. I am so taken with that idea that the reader will most likely find many mistakes in this thesis - the sole purpose being, of course, to remind us just how limited the human intellect is and how unable to portray spiritual matters appropriately.

FOREWORD

The objective of this study is to help dispel the widespread view that Buddhism and Christianity are irreconcilable. To this end Christian-Buddhist dialogue has already accomplished a lot. Hence it may no longer be difficult for many people to concede that there is a kinship between the two religions as far as their basic emphasis on ethics, compassion, and spiritual rather than worldly values is concerned. But when it comes to the core, namely how does each religion think of the absolute and consequently of reality as a whole, most people still think that Buddhism and Christianity are incompatible.

It is true that much of Christian and Buddhist theologies and philosophies are indeed quite distinct. One generally affirms a real God who created a real world. The other negates a creator-God and often also the reality of this world. Buddhist philosophy calls this absence of any reality that could be grasped as truly existent "emptiness".

However, even in regard to the absolute there are Buddhist and Christian schools of thought that are very much akin. This thesis seeks to show that Shentong Madhyamaka and Mystical-Negative theology are one example. Although Shentongpas do not negate the validity of emptiness, they nonetheless affirm (in a certain way) positive characteristics of the absolute such as existence, wisdom, compassion, and even form. And although Mystical- Negative theologians do not negate the usefulness of thinking of God as the Creator, they also speak of an absolute reality that transcends all human concepts of existence and non-existence, Creator and created.

It is obviously not my intent to add arguments to the rhetoric of those who would prove Shentong Madhyamaka "unbuddhist" because of its similarity to theism, or negative theology "unchristian" by pointing to its kinship with Eastern thought. On the contrary, my hope is that religious people around the world can learn to rejoice in their commonalities without fearing a loss of identity. Hopefully it will become clear that in spite of all commonalities the Blessed Angela of Foligno, one of the greatest medieval mystics, is very Christian; just as the Omniscient Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen, who systematized the Shentong Madhyamaka, is very Buddhist.

Hence, other preconceptions I would like to help dispel are those concerning what the "mainstream" or "majority" of Christians and Buddhists believe or do not believe. Narrow views of what it means to be Christian or Buddhist are often held not only by outsiders of different faiths but equally by masses of insiders who think of their particular species of tradition (or denomination) and school of thought as the standard for their whole family of religion. Yet it would seem that two thousand or more years after their founders left their bodies, it is time to concede that each and every Christian or Buddhist sect is but a variation on a theme. Unless we want to continue a tradition of religious intolerance, wars and persecutions, we have little choice but to accept that neither religion has produced only one "mainstream" or "true" form of its tradition. Both religions include such a plurality of distinct teachings, practices, approaches and denominations that one may even dispute the propriety of referring to Buddhism or Christianity in the singular.

If we can embrace all Christian and Buddhist traditions (as well as other religions) as true and authentic, it then becomes meaningful for dialogue to find parallels between certain traditions, even if inevitably others do not consider them "mainstream". For if all schools can be respected by other schools within that religion then, in order, for example, for one particular Buddhist concept to be respected by Christians, it no longer has to match all of Christian doctrine and practice; it suffices if it is akin to one particular Christian school of thought.

Naturally I have other presuppositions that are bound to color my work. While objectivity remains a worthwhile guideline, the academic community has begun to acknowledge that it is impossible to achieve. Therefore it is a matter of academic honesty and accuracy for me to disclose the religious institutions that have framed my thinking.

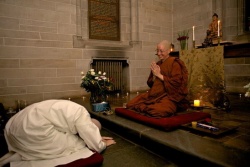

I was brought up Protestant in Germany. Since 1983 I consider myself a Christian Buddhist. I practice Tibetan Buddhism. My guru, the late Kalu Rinpoche (1905-1989), was not only the head of the Shangpa Kagyu lineage but also one of Dolpopa's Jonang lineage holders. Under normal circumstances this would mean that Dolpopa's practices and teachings have been transmitted to him via an uninterrupted line of masters and disciples (Sanskrit, hereafter Skt., parampara) going back all the way to Sherab Gyaltsen himself. But since the Tibetan government banned the Jonangpas in the second half of the seventeenth century, the transmission that reached Kalu Rinpoche, while authentic, was apparently not as complete as it should have been.

Since I am mystically inclined, and since Tibetan Buddhism has much more in common with Catholicism than with any other Christian denomination I am personally familiar with, my Christian parts feel most at home in the Catholic church.

According to constructivist thinking, which will be elucidated in the introduction, I could never be sure whether I understand what Dolpopa (or, for that matter, any other ancient Buddhist master) tried to say. And I must admit that my knowledge of Sherab Gyaltsen's philosophy is quite limited. I am not Tibetan; my Tibetan language skills are extremely limited; and, as will be explained in section IV.A.2. "Dolpopa's Works", Western knowledge of his teachings in general is quite scarce. On the other hand I am a practicing Buddhist who has been steeped in Shentong thought by a master who was just about as closely linked to Dolpopa as anyone could be in our era. Furthermore I am relying, to a great extent, on the accounts and translations of excerpts given by Shenpen K. Hookham. She is a very serious Buddhist practitioner and also received teachings on the subject from Jonang lineage holders. Moreover Cyrus Stearns, a Western authority on Dolpopa, has confirmed during a conversation that my understanding of the master's thought was good. Hence I believe that while my grasp of Shentong doctrine is limited, it is reasonably accurate.

A note on methodology: Within the framework of this thesis it is essential to investigate the philosophical, historical, and social background of Dolpopa's and Angela's teachings. Without such work they would be difficult to evaluate, especially because very little of Dolpopa's teachings are directly available to me and because Angela's words were edited to a great extent as soon as they were spoken. On Angela's side this requires some feminist analysis of her tradition, time, and sayings. By taking such factors into account, one can begin to sift out which statements best reflect the core of their experiences.

My approach is based on the perennialist view which allows me to be "interreligiously engaged". I do not believe in the myth of neutral scientific research. The eerie regularity with which "neutral" academic studies have been used for destructive ends compels me to be quite frank about my socio-political goals: I want Buddhists and Christians to know, respect, and help each other.

As much as possible, I will try to refrain from interpreting Angela's revelations from a Buddhist perspective. It may at times seem to Christian readers as if I were superimposing Buddhist structures onto Christian thinking. In determining whether this is really the case, one must remember that Mystical Theology by definition transcends ordinary theology as Christians know it. Thus it is conceivable that Christians, even more so than Buddhists, may be prone to read their own presuppositions into Negative Theology.

As appropriate for inter-religious dialogue, I will depict events in an emic (insider) rather than etic (outsider) fashion, analyzing what occurrences mean to those experiencing them, not how outsiders might interpret them.

Sanskrit words that are not printed in italics and bear no diacritical marks can be found in Webster's Third New International Dictionary and can therefore be considered English words. Regrettably the dictionary we are following, leaves the diacritical marks out without changing the spelling so as to reflect proper pronunciation. May the reader be advised that c is always pronounced ch and s is often pronounced sh, for example sunyata is read as shunyata.

Comparing the teachings of Angela, a Christian woman, and Dolpopa, a Buddhist man has the added advantage of revealing how gender has influenced philosophical expression. The disadvantage, in this case, is that all the inescapable feminist critique is directed against Christianity, while Buddhism is spared that embarrassment. To avoid a wrong impression it should be noted that the situation of Buddhist women was comparable to that of their Christian sisters. Their only advantage was that they were never physically persecuted and slaughtered as witches or heretics, as were Christians. But in their spiritual development Buddhist women probably received less support than Christian women did. When all is said and done it is probably safe to remark that Buddhist women have been just as oppressed as their Christian sisters. It took, however, much more effort on the Christian side to secure women's subordination. Let me briefly explain, for these issues play an important role in this study.

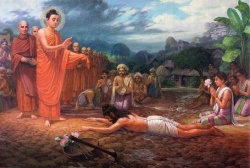

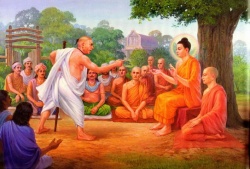

Jesus threatened patriarchy far more than Buddha Shakyamuni did. Judging by the sutras, Gautama was a sexist who had to be persuaded by his favorite disciple to allow the ordination of women as nuns. He only agreed to this wish after fixing women's subordination in the rules of the order and predicting that because of women's presence it would last only five hundred instead of one thousand years. He made it quite clear that spiritual truths were not to interfere with the social hierarchy. No matter how enlightened a woman was, she was socially inferior to the youngest monk. And no matter of what cosmic significance it may have been to join the Buddha's order, one was not allowed to do so without the permission of parents and kings. In short, patriarchs had nothing to fear from the Buddha.

Jesus on the other hand was much more subversive. To follow him explicitly meant to break with all hierarchy of gender, classes, and personal interaction. He constantly went against social customs that were discriminatory against women, the poor, or any detested group. And he demanded from his disciples that they not abide by customs that stood in the way of following him immediately and one- pointedly. No wonder women were drawn to him and his teachings in great masses, probably outnumbering the men. For at least three hundred years their lot was significantly improved and they probably never expected this development to reverse.

To "re-establish order" in the patriarchal sense took great effort on the part of church men more than once in the history of Christianity. It required not only the intimidation, persecution, and murder of women but also the suppression of many Christian teachings and practices, including the Via Negativa.

That is why the subordination of women is to be dealt with in this thesis. It is heart breaking and representative of the suppression of humanity all over the world. I say 'humanity' because in order for men to suppress women they also have to suppress other things, including great parts of themselves. The Catholic church is an example, not an exception in this.

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

A.In Search of a Common Language

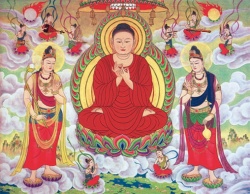

Each religion has created its own jargon some of which is easily translated into the language of other traditions while other portions are not easily transferable. Part of the task of interreligious dialogue is to find a language that all conversation participants can accept. In this thesis, and perhaps in all interreligious dialogue, one of the most important tasks is for dialogue partners not to be disturbed by each other's terms for the absolute. Many Buddhists, for example, are very uncomfortable with the thought of addressing the ultimate as "Lord" or "divine". Yet the Buddhist tradition knows many Lords. For example the Lord Avalokiteshvara (Tibetan: jo bo spyan ras gzigs), who embodies the love and compassion of all buddhas. Buddha Shakyamuni as well is often referred to as Bhagavan Buddha, which literally means "the Sublime" or "Holly" and is a Hindu appellation for God. He is also said to possesses "the divine eye" and "the divine ear". Not altogether unlike the Christian God, the Buddha came to embody

absolute truth or reality, and many seekers of enlightenment interpret everything they meet with as "the blessing of the Buddha". Of course I do not mean to say that there is no difference between the Christian and Buddhist Lords. But one need not be overly sensitive; and foreign words should not detract from possible commonalities.

Particularly Western Buddhists often overreact to language they consider loaded with Christian thinking. A good example is Alex and Hideko Wayman's use of the term "uncreate (reality)" rather than "uncreated". Apparently they prefer using a grammatically incorrect word to a Buddhist term that might be shared with Christians. Others may insist that there is a tremendous difference between Absolute and absolute, one designating a more reified or personalized reality/being, the other an abstract variable.

In the search for the most correct and acceptable words one would do well to remember that there is probably not one important Christian or Buddhist term that is used and interpreted consistently within its religion or even within any one denomination; not the absolute, or God, or divinization, enlightenment, or emptiness, or buddha nature. Any one of such terms has been filled with a wide variety of meaning in its own tradition, why should one cast one of them in concrete when entering dialogue? Interreligious encounter would certainly be easier if all participants could admit that their own religion has not come to an unanimous agreement concerning definitions within their own language.

So when I use lower case for words like 'the ultimate', this does not mean that it would be inappropriate to regard the designated reality with great respect, awe, or love. For example, when many people agree that Belgium is a country in Europe, this does not mean that they all have to feel the same way about it or have exactly the same information about it.

In an effort to use the most neutral terms available, I will call 'the absolute' unconditioned, ultimate, or uncreated when describing it in a way relevant to both Christian and Buddhist traditions. When the word "reality" is used in conjunction with these terms, it refers to the absolute as viewed from an ordinary, relative viewpoint. When it stands alone, it reflects the view that "relative reality" is not separate from, but an aspect of the ultimate.

Furthermore, I have not put terms that are only used within one religion and perhaps not condoned by the other (like God, Spirit, or buddha nature) in quotation marks so as to accommodate those who would doubt the adequacy of these words for describing the relevant reference. For example, I will not question whether in each one of Angela's visions it is truly God who speaks to her. As long as it is consistent with her own tradition to say that the things she sees or hears stem from the Holy Spirit, that should be an acceptable way, within interreligious dialogue, of expressing the occurrence.

B. Perennialists and Constructivists

Elucidating, as I do in the second half of chapter V, how Buddhist and Christian teachings could help each other overcome some of their own limitations, presupposes that representatives of both religions can and frequently do experience the same reality and are able to realize highest enlightenment.

This is what modern religious studies scholars call a "perennialst" view. For decades Western thinkers have debated the character of cross-cultural mystical experiences. Two camps have evolved, the "perennialists" and "constructivists". Their controversies deal with the following issues:

(1) Is there one absolute reality that permeates and transcends all cultures and religions?

(2) Can it be experienced in a pure, unmediated way or is (as constructivists maintain) all experience of reality colored, shaped or constructed by the cultural, religious, linguistic, historical, and conceptual biases of the experiencing subject?

(3) Even if people of different cultural and linguistic backgrounds had the same experiences, could they ever ascertain this, or can a person from one cultural- linguistic background never be sure that s/he correctly understands a person from a different background?

(4) Some constructivists combine the first two questions and maintain that since what is perceived as absolute truth varies and depends on the practices and views of the individual, one cannot speak of one absolute truth but must acknowledge a plurality of relative truths that only seem to be absolute.

My first reason for adopting a mostly perennialist perspective is that it appears to be the view best suited to support religious tolerance and a profound kind of interreligious dialogue that goes beyond just getting to know each other. Only on the basis of acknowledging a common ground to all human experience in general and to mystical experience in particular, can dialogue lead to deep mutual respect and to a positive transformation of all partners. Some are afraid of such transformation because they worry about the purity of their faith and the possibility of syncretism. Others stress that in the present state of our world, religious institutions must take some risks and acknowledge their responsibility for promoting world peace by bringing peace to interreligious relations.

Another reason why I lean towards perennialist views is that I find constructivist arguments alienated from human realities, perhaps in a typically "academic" way. If it were true that "language itself constitutes the encompassing horizon of life and thought" and that "there is no experience independent of language", would that not mean that babies and toddlers do not experience reality until they are able to speak? Surely psychology would prove such a notion wrong. (Or does body language, laughing and crying in different intonations count as language?) If language and culture determined how we experience reality to the point where one could never truly understand statements made in a foreign language, why do we study different languages, cultures, and history? Would this not be a futile and meaningless endeavor?

I wonder how much time the leading constructivists have spent in other countries and how well they speak foreign languages. Have they ever immersed themselves in a foreign culture and experienced the clarity with which one knows whether one understands the other not at all, partially, or quite fully? Based on my own experience of having spent years in foreign countries and being fluent in four languages, I can report that humor is one good indicator of how well one understands a foreign culture. It took me two years of living in the USA before I could find at least some American news paper comics funny. On the other hand in India it took me less than a month to be just as entertained by watching Westerners as my Indian friends were.

Furthermore, if language is the all-decisive factor in human reality, how would one evaluate dialects. German dialects for example vary to such a degree that people from Southern, Central, and Northern Germany cannot understand each other when they speak in their respective tongues. And although I know the dialect of my hometown to some degree, when it is spoken in its pure form, I understand less than if someone spoke to me in French. Nonetheless one could not deny that all Germans, and especially the people of Cologne, share much of the same cultural reality.

Moreover, if all our experiences were constructed by biases, could we ever be surprised? How would one explain the frequent shock and disbelief of mystics when they reflect on their experiences? How would one interpret Angela's statements that things were revealed to her of which she had never heard before, which were not taught in churches, and which preachers would not understand?

I would conclude that it is possible to experience reality immediately. I also believe that one can learn enough about a foreign language, culture, and historical epoch to understand what its natives are trying to communicate. In John C. Maraldo's opinion, understanding a spiritual tradition requires learning its "language" by practicing it. He says:

Part of the way we transform the chaos of sounds in a foreign language into meaningful utterances is by actually venturing to speak in that language. We learn to hear clearly by practicing speaking. Sometimes a religious tradition appears to speak in a foreign language, and we learn to translate by practicing within that tradition.

According to such reasoning, practicing two religions (as I do) should be a hermeneutical advantage in comparing them.

The most significant reason, however, for basing this thesis on at least some degree of perennialism is that without such an attitude neither Buddhism nor Via Negativa make any sense. Neither Buddhist nor Christian schools usually question the existence of one absolute reality. Buddhists may say that it is not graspable in words or concepts and that any comprehensible reality is an illusion, yet they always presuppose the ability to awaken to the one true reality. If Buddhists did not believe that humans are able to deconstruct all their gross and subtle biases and realize one ultimate reality, they would have to renounce enlightenment, the very core and raison d'etre of their religion. At times it may seem as though they did just that. But even when some masters say that there is no such thing as enlightenment, they do not hold their own words to be true to the point where one should act on them, for they are only a partial truth. When it is taught that nirvana is an illusion, it does not mean that monks should go home and stop meditating; it is taught precisely for the purpose of reaching (an ineffable) nirvana. As Nagarjuna says: "Without dependence on everyday practice (vyavahara) the ultimate is not taught. Without resorting to the ultimate, nirvana is not attained."

Similarly the Via Negativa depends on the presupposition that wo/man is able to forget all cultural and linguistic biases or to cover all s/he has learned with a "cloud of unknowing". Again we find here the statement that the deconstruction of all presuppositions is possible (even if rare and difficult) and constitutes the path to perfect, unmediated union with the Uncreated. Furthermore many mystics insist that their experience of the absolute transcends all possibilities of verbal description.

Hence the Buddhist as well as Christian mystics who will be encountered in this thesis have strong perennialist tendencies. To discount their accounts one would have to question either the very validity of mysticism (which aims at direct, increasingly less mediated, encounters with the absolute) or the mental health of many of the greatest mystics. This is not the place to argue the case of mysticism. It must suffice to say that many Christians as well as most Buddhists generally accept mystical insight as a "valid means of cognition". As far as the mental health and intelligence of mystics is concerned, it was never taken for granted. Both Dolpopa and Angela were suspected, questioned, and challenged. Yet, although people at times disagreed with their views, their contemporaries certified, after thorough investigation, that they were neither possessed by the devil, nor crazy, nor stupid. Rather, as their titles clearly point out, the Omniscient and the Blessed were acknowledged as personifying the pinnacle of human development.

Thus, unless one is strongly predisposed against all forms and expressions of mysticism, I see no reason to believe that in comparing Angela of Foligno and the Via Negativa with Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen and Shentong Madhyamaka one is relating two comparable delusions. Nor, since both come to very similar conclusions, would it make sense to declare one completely mistaken but not the other.

Nonetheless it must be acknowledged that many Christians as well as Buddhists who display strong perennialist tendencies might, for various reasons, also sympathize with constructivist notions.

Many might like the idea that one cannot ascertain that mystics from different religious backgrounds experience the same reality. Such an argument appears to accommodate the claim of so many Buddhist and Christian schools that only they lead to the highest goal attainable. It seems to be common among exclusivists to explain the experiences of followers of other traditions as being constructed by biases and therefore not absolutely true. Meanwhile their own biases are excluded from such a constructivist critique and are taken to be absolute or at least uniquely true.

Furthermore, Buddhists may be drawn to constructivism because they have a strong millennia old tradition not only of perennialism but also of deconstructing reality by means of logic. As we will see, many Buddhist schools have embraced a combination of what might be termed perennialism and constructivism. For example, Shentong Madhyamikas and their predecessors speak of two nirvanas, two buddha- gotras (buddha family), or two purities. One set is relative and conditioned; it is reflected in the constructivist view. The other set is absolute and changeless; it is mirrored in the perennialist position.

Angela of Foligno and Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen also both transcend the constructivist-perennialist controversy when they speak of an absolute reality that is at once one and a union of many, one reality with many modes or qualities.

To conclude this debate, I am inclined to agree with John Cobb Jr. when he says that: "both [perennialists and constructivists] are correct in fundamental ways, although wrong in excluding one another." In my opinion neither one of these camps, when taken to an extreme, nor Lonergan's "Interiority Analysis", represent satisfying theories; they tend to be one-sided. I think Queen Srimala's proposition of a constructed and an unconstructed conventional as well as ultimate reality (samsara and nirvana) is a very intriguing concept that Western scholars would do well to explore in greater depth.

C. The Role of Mystics and their Teachings

Comparing, as this thesis proposes to do, teachings on the essence of absolute reality is a delicate matter. In doing so, one is dealing with something that lies beyond ordinary perception and human concepts; something that cannot adequately be described in words. What then can mystics say about uncreated reality that will at least point our gaze in the right direction? For something must be said. How many mystics tried to be silent because they found the truth to be inexpressible but were commanded to speak anyhow? When the Buddha thought it would be useless to speak about the reality he had awakened to, because no one would understand it, the Hindu god Brahma Sahampati appeared before him, imploring him to teach. Similarly, many Christian women mystics were commanded by God or the angels to speak though they tried everything to remain silent.

Some mystics' role is to confirm the existing tradition. But the greater ones, in my opinion, are in the dual position of affirming as well as negating their religion. It is their function to be outrageous, to burst through the limits of their religion in order to be more true to that which is limitless. As Raoul Mortley says, what the Via Negativa negates of God is "parasitic on prior affirmations [the negations] cannot invent themselves." I.e. Negative theology negates not just anything, but precisely what was first affirmed. Nor would it negate certain characteristics if they were not generally established as positive truth. Correspondingly, what Shentong Madhyamaka affirms of the absolute is parasitic on prior Madhyamika negations.

Both traditions are rooted in agreement with their religion but also point to their limitations and try to overcome them. That is why mystics of the Via Negativa are drawn to negate God, while Shentong Madhyamaka type mystics are drawn to affirm a quasi theistic absolute. But these teachings cannot be independent; they draw their life blood from a tradition which they transcend. If they come to be understood as autonomous they lose their initial purpose. Then they will exchange positions; the former parasite will become the host and vice versa. In Buddhism this happens more easily than in Christianity because there is no strong centralized institution that freezes the status of host and parasite.

The way this dynamic is played out in a religion is in the relationship between exoteric and esoteric, or public and "secret", "hidden", "special" teachings, or between officially established doctrine and freely improvising mysticism. And if what has been said sounds confusing, it is precisely because in the history of both Buddhism and Christianity this relationship has been anything but clear. In both religions there is conflict as to whether or not there should be graded teachings. The Catholic church has long accepted a difference between teachings and practices for the laity and for the ordained, but has never openly acknowledged the existence of esoteric teachings. And this although the Bible contains quite a few references to graded teachings corresponding to the understanding of the audience or to teachings whose mystical depths will be understood by some while others may hear the words but not grasp any of the more subtle meaning. There is also mention of spiritual secrets that will be revealed to some but not to others. Clement of Alexandria (second century) speaks of secret teachings that were transmitted from the time of the apostles and hidden in scripture under symbols and allegorical language.

There has been wide-spread agreement in the Christian world that the Negative Way is not suited for beginners. But whether or not it should be the pinnacle of the contemplative way has never been clearly decided.

In Buddhism the situation is even more controversial. Nikaya-Buddhism generally does not acknowledge any esoteric instructions. Yet, most of traditional Mahayana Buddhism explains its very existence as secret teachings of Buddha Shakyamuni to especially advanced disciples. But once the Mahayana had become established as public, another layer of special oral instructions was added to it. Of what these consist or even if there are any at all, varies from school of thought to school of thought. As will be explained in section II.B.4. "His Person", Dolpopa's revolution consisted of little more than an attempt to change the status of "special instructions" to that of public normative doctrine.

What further complicates the issue of esoteric teachings is that religions keep certain teachings secret for a multitude of reasons. There are spiritual considerations for the development of individuals, but there is also concern for the identity, establishment, and expansion of religious institutions. And finally there are connections between these institutions and worldly powers that make churches of all religions seats of political power. Once they have become entangled in worldly struggles for control, it is often difficult to sort out purely worldly from spiritual motivations.

As we shall see in the cases of Via Negativa and Shentong Madhyamaka, their health, status, and expansion, or as the case may be, suppression, were rooted in all these areas of religious life: personal, institutional, and political affairs of state. What Dolpopa and Angela communicated of their visions always took the status of their more hidden tradition into account. In Angela's case this meant silence in order to comply with official church doctrine. In Dolpopa's case it meant rebellion and abundant writing in the effort to prove his orthodoxy.

When contemplating the spiritual reasons for regulating access to certain teachings, expounding on what has been kept a secret so diligently seems inappropriate. But when considering that the Via Negativa has been so hidden within the Catholic church that few know about it and even fewer are able to connect with it as a living tradition, it seems desirable to proliferate knowledge of it more widely than would be advisable under different circumstances. In so doing, hopefully a balance can be regained between the faithful knowing of its existence and not being able to explore all the details without spiritual direction.

On the Buddhist side the situation is different. So long as teachings contrary to the normative doctrine were treated as secret instructions, the powers of church institutions and state were not bothered by their contents. Thus Dolpopa's teachings survive as a practiced tradition, even if kept a little more hidden than he had perhaps intended. Today much of his thought is openly shared, except where it enters Tantric territory, which is generally secret. Though I have tried to persuade three great lamas to explain certain mysterious issues, they revealed very little.

And so this thesis will treat some of what Angela and Dolpopa shared of their treasures though for many reasons much of their revelations remain secrets.

As a perennialist I believe that these mystics can help us gain a fuller image of reality. I also hope that their findings can be expressed in a language that facilitates Christian-Buddhist communication.

CHAPTER TWO

THE CHARACTER AND HISTORICAL ROOTS OF VIA NEGATIVA

AND UMA SHENTONG

A. What Is Via Negativa?

Via Negativa is a way of approaching God by denying self, the world, and finally the ability to conceive God. When it is expressed in theological terms it is called Mystical or Negative theology and professes that one can only say what God is not, not what God is. Even merely stating that God always remains a mystery that no one can comprehend completely and that no words can describe adequately, is often considered "Negative theology". Though many people use these terms interchangeably some distinctions can be made.

When facing the divine mysteries, even scholastic theology admits that its talk of God is only an approximate analogy, not a true description. "In this sense negative theology is an essential element of the theology of all times" , though some thinkers have stressed it more than others.

Via Negativa, which is a prime focus of this study, is more radical in its denials and the mystical sibling of scholastic Negative theology. Both posit God's ultimate transcendence and inconceivability, but they do so from different points of view and draw quite distinct conclusions.

Scholastics approach God from an intellectual point of view and thus his unknowable nature presents to them a final and insurmountable gulf between wo/man and God. They conclude from this gulf that humans will in essence always be separate from God and that they have no inner tool whatsoever for knowing him directly and empirically. Thus, in their view, any human knowledge about God depends exclusively on what is revealed and recounted in scripture about the incarnate Word. Furthermore, supposing wo/man's incapacity to know God directly, salvation comes to depend completely on the mediation of the Church and its officials.

On the other hand, when the mystic says that God is inconceivable and "unknowable", s/he is coming from a direct experience of the divine that shattered all s/he thought s/he knew. Now s/he no longer knows the God of scripture intellectually but s/he has become one with a completely transcendental unnameable reality. As St. Gregory of Nyssa (c. 330-395) puts it: "The Lord does not say that it is blessed to know something about God, but rather to possess God in oneself." Here God's transcendence of the human intellect does not make him inaccessible, it just warrants a specific approach if one is to become one with him. More than a theology, the Via Negativa is a method of contemplating the divine stripped of ideas and bare of any human concepts yet full of a loving yearning that knows neither object nor subject. As Dionysius the Areopagite says, one is to strive for complete "unity in unknowing fashion with the one superior to all being and knowledge." Such "unio mystica" brings the soul so close to God that there is no room between them for any dogmas, theologies, beliefs, or even the Church. Then the soul becomes "divinized", i.e. one with God with very little or no distinction, depending on whose teaching one follows. At this highest stage of union there is consciousness and things are "seen", but Christian mystics sometimes call it "unknowing" , because in this state the soul knows of neither world, nor soul, nor God. What it experiences is inexpressible.

Yet what is revealed during union with the absolute often demands to be communicated. When the contemplative obeys, the result is not a teaching based on studying books, but an "infused theology" (inspired by the Holy Spirit) that stresses all the things God is not. It is quite radical in that it negates in a transcending way, most everything that is said in the Bible. For example Denys says:

The cause of all things intelligible in its pre-eminence is not any of the intelligible things. . . . It is not life, nor being nor eternity. . . . It is not truth, nor kingship, nor wisdom; not one, nor unity or goodness; nor is it a spirit as is visible to us, not sonship, not fatherhood. . .

Yet "infused theology" does not render the Scripture useless. Rather, it follows the regular path to holiness as it is laid out in the Bible. Only when the apostolic ideals are realized can the affirmative way be transcended for the sake of indistinguishable unity with the divine. The Bible contains the most holy part of all human concepts within "created reality". Nevertheless no intelligible thing is relevant in regards to the "Uncreated". Within created reality God's qualities are celebrated, but when speaking of the Uncreated, even God's existence cannot be affirmed. Instead, as Denys puts it: "the cause of all things intelligible . . . is beyond affirmation, and beyond all denial."

Denys indicates that these teachings were meant for those who had been "initiated" into the divine mysteries by having been baptized not only with water but also with the Spirit. The Via Negativa was a method for those who had dedicated their lives to striving for union with God by way of asceticism and contemplation. As Lees explains, much of the Negative theology of St. Gregory of Nyssa "was directed to furnishing the newly-founded monastic movement in Cappadocia with a substantial literature expounding the theological basis for the contemplative life." It was a theology that was congruent with individuals making every effort to uncover the divinity that lay hidden inside or underneath their souls. (Depending on whom one follows.)

The distinction between scholastics and church men on the one hand, and mystical hermits on the other is, according to Louth, a later invention of the West where spirituality became separated from dogma. He states that: "in the Fathers, there is no divorce between dogmatic and mystical theology;" Even much-later theologians such as Thomas Aquinas (1225?-1274) managed to maintain for themselves a mystical side. Nonetheless, the fact that mysticism and dogmatism were not "divorced", does not mean that they were indistinguishable. It seems to me that the early church Fathers struck a different tone, depending on the function they were fulfilling: mystic or church man. Some of the confusion about Negative theology seems to stem from the fact that their mystical teachings changed just a little when they tried to accommodate the concerns of the church institution. Those slight alterations unfortunately had tremendous consequences which the Fathers may not have foreseen.

Thus we have not only a mystical Via Negativa and a scholastic Negative theology but also a grey zone between the two, marking an ongoing meeting point as well as an historical transition. Sometimes the distinction lies only in the motivation or the inner experience of the author. That's why it is at times difficult to discern which spirit speaks through a Negative theologian: the mystic or the church bureaucrat. And thus it happens that great contemplatives like Athanasius (295?-373) and Gregory of Nyssa are at times accused of rejecting mysticism.

So in spite of the importance of distinguishing between Via Negativa or Mystical theology on the one hand and purely scholastic Negative Theology on the other hand, I use the term Negative Theology interchangeably with Via Negativa or Mystical theology, although the first two expressions will be reserved for the more mystical sibling.

B. What Is Shentong Madhyamaka?

Madhyamaka (Sanskrit) means "of the middle". It is translated into Tibetan as uma (dbu ma = middle). Since the "Middle School" is known in the West by its Sanskrit name, either term is used in this thesis, depending on whether the reference is to the Indian or the Tibetan context.

Madhyamaka is the name by which the Indian master- philosopher Nagarjuna (second/third century) called his philosophy, referring back to Buddha Shakyamuni's Middle Way of avoiding extremes (Madhyama-Pratipad). Nagarjuna's teachings can be summarized as expounding that all phenomena, including any kind of "Absolute", are empty of a conceivable existence as well as a graspable non-existence. Things appear in a relative way, but they are free from an independent, real self that can be established, i.e. "self- empty" (Tibetan: rang stong, hereafter 'rangtong'). Since nothing correct can be said about reality, the only flawless position to take is to not take any at all. In his Madhyamakakarika 13:8 Nagarjuna explains that emptiness is taught as an antidote to all views (Skt. drsti), not as a view itself. He declares grasping at emptiness as though it were a philosophical position the most difficult view to remedy. (This did not keep Madhyamikas from spending much time and effort refuting everybody else's position. And it has been argued from early on that this in itself constitutes a position. )

The Tibetan word shentong (gzhan stong) means 'empty of other'. Uma shentongpas agree with the statement that all phenomena are self-empty, but they do not agree with Nagarjuna's (as well as Tibetan Rangtongpas') position that ultimate reality is empty of self-being just like any other phenomenon. Rather they profess an absolute which transcends phenomena, truly exists and is full of real qualities. It is empty only of any accidental defilements or qualities that are other than its very nature, that is to say anything not absolute like defilements, dualistic perception, and graspable qualities that could be separable from its essence, etc.

Tibetan Shentongpas and their Indian predecessors refer to this ultimate reality as tathagatagarbha (or Tib. de bzhin gshegs pa'i snying po). This term is alternately translated as: buddha-embryo, -seed, -womb, -storehouse, - nature, -essence, or -core. Buddha nature is a rendering that only became acceptable in China because it implies a quasi substantial essence that pervades not only all sentient beings but the whole universe, including matter. More often than not, Indians shied away from such a use of the term. But it is implied and in some cases even explicitly stated in a number of Indian texts. Therefore I use the term "buddha nature" when describing Indian ideas wherever this seems appropriate.

In how far it is justified to call Uma Shentong a Madhyamika system, is a complex and much debated issue that is dealt with in later chapters.

The Philosophical Category of Shentong Thought

As opposed to Negative Theology, the Shentong school of thought enjoyed centuries of public recognition and support, though it was never unrivaled. Rather, the debates involving its Indian forerunners continued in Tibet and still excite people to this very day. The controversy has been carried out in public with heated enthusiasm but most of the time also with a decent measure of good will and tolerance towards the opponent. This led to Shentongpas developing perhaps a little more of a philosophical footing than their sisters and brothers of the Via Negativa did.

Nonetheless, Michael Broido seems to maintain that Dolpopa never aspired to compose philosophy but merely recounted his own personal experience. He emphasizes the distinction between siddhanta (grub mtha') and darsana (lta ba). According to the "Lexikon der östlichen Weisheitslehren" a siddhanta is "the opinion [or view) of an Indian philosophical school that is fixed by written transmission and argumentation and collected in a compendium." Darsana on the other hand means "seeing". In Buddhist contexts it denotes:

a realization that is based on reason and able to extinguish intellectual passions, wrong views, doubt, and attachment to rituals and rules. The path of seeing (darsana-marga) leads from mere faithful trust in the Four Noble Truths to actually realizing them.

According to Broido, Dolpopa reserves the term siddhanta for Rangtong Madhyamaka and never intended to present Uma Shentong as a fixed philosophical system. Broido stresses the different areas siddhantas and darsanas cover, one referring to philosophical systems, the other to the experience of seeing the way things really are. He seems to think that siddhantas are something higher or more real than darsanas and that Dolpopa never intended to elevate the account of his realization to the level of philosophy. He accuses "modern Shentongpas" of not maintaining the master's clarity and instead confusing accounts of mystical experience and epistemic teachings on how to acquire insight with a philosophical system. By doing so, Broido maintains, they read an ontology into his Madhyamaka teachings that is not there. But can he, on the one hand, profess to understand Dolpopa better than modern Shentongpas do when he, on the other hand, denounces the master's teachings on absolute form as an "absurd ontological view"? What he fails to recognize, in my opinion, is that to the mystically inclined Shentongpas direct experience seems far more able to reveal the truth than "a fixed philosophical position based on axioms and set rules of argument". To a Shentongpa, the latter will by its fixed nature always be dualistic. As Hookham explains in her section on "Direct Experience as Valid Cognition", in order to determine which means of cognition is most suited for which object of cognition one has to analyze the characteristics of the means and the object. Then it becomes apparent that reason and inferential logic can only know concepts but not the true nature of reality. Since the latter lies beyond the conceptual mind, only direct yogic awareness (Skt. yogi pratyaksa) represents a valid means of cognizing ultimate reality.

Nonetheless, a darsana is not incapable of philosophy. As the Lexikon says it is based on reason and leads to the realization of all that can be realized and to the eradication of wrong views. But perhaps it is not stuck in fixed philosophical rules. Shentong Madhyamikas strive to encompass the purpose of Madhyamaka and to transcends it.

In this context it is important to consider that to divide Buddhist teachings into Western categories of philosophy, epistemology, ontology, soteriology, pedagogy, etc. is most often a superimposition. The results are misunderstandings and accusations such as Broido's: "Note Kong-sprul's typical confusion of epistemology with ontology." Is Jamgon Kongtrul the Great really confused? I think the problem is that Western scholars like Broido sometimes forget that in a system where what ordinary people call "reality" is seen as a mere misconception, an illusory projection of the mind, there is no distinction between "epistemology" and "ontology". (This is true for all schools of thought that were influenced by Cittamatra thought, including many Madhyamika thinkers.) Dolpopa backs his view that different realities are merely different ways of perception or different levels of realization with the following quote from Nagarjuna's Mulamadhyamakavrtti Akutobhaya:

(Seeing that circumstances arise is called] worldly samvrtisatya" . . . ; it is the relative truth (samvrtisatya) because of the two (truths) it is the one which is true in the relative sense. Seeing that circumstances are free from arising, . . . is called "paramarthasatya"; it is the absolute truth because of the two it is the one which is true in the absolute sense.

It is in keeping with Rangtong critique to judge Uma Shentong as too ontological to constitute Madhyamaka. Yet Indian pramana (=proof) literature accepts direct or yogic perception as a valid means of cognition. And does something being correctly perceived and validly cognized not allow the inference of its ontological status to be existence? For how can something be validly cognized if neither a cognizer nor a cognized exist? According to Paul Williams, even "Tsong kha pa observes that if the ultimate truth doesn't exist then there is no way it could be eventually cognized and the holy path would be pointless." Nevertheless he continues to show that: The formal difference between the dBu ma rang stong and the dBu ma gzhan stong marks the situation of Madhyamaka anti-ontology in opposition to the felt needs of the mystical as a content-bearing experience.

In short: shentong doctrine is the account of the shared experiences of many masters who have validated their encounters to reflect an inconceivable but existent reality. It contains descriptions of mystical encounters with the absolute formulated, as much as possible, in accordance with philosophy. It also encompasses psychological explanations of what is helpful on the path to realizing ultimate reality. Broido may call it a "frequently made ridiculous claim" that the contrast between Uma Rangtong and Shentong lies in relying on reason rather than faith as the primal force to guide one to enlightenment. It is nonetheless true and in accordance with much of the tathagatagarbha tradition. For example in the Srimaladevi Sutra the Buddha says: Queen, whatever disciples of mine are possessed of faith and [then] are controlled by faith, they by depending on the light of faith have a knowledge in the precincts of the Dharma, by which they reach certainty in this.

The Ratnagotravibhaga, summarizing this sutra and the Mahaparanirvana Sutra, echoes: "This, the Absolute, the Self-Arisen One, is realizable through faith. The disc of the sun blazing with light is not visible to those without eyes."

Williams summarizes the Jonangpa position very well: When one goes beyond reasoning one realizes something new, a real, inherently existing Absolute beyond all conceptualization but accessible in spiritual intuition and otherwise available, as the Tathagatagarbha texts stress, only to faith.

C. The Development of Via Negativa

Wherever Christian mysticism was allowed to flower, one of its blossoms was the Negative Way. Correspondingly, whenever it was strictly regulated or suppressed, the Via Negativa was the first to wilt and die, until its next spring. Thus, the history of Via Negativa is the history of Christian mysticism.

1. Biblical Roots

Two Biblical elements contributed to the development of Via Negativa: On the one hand, God's absolute transcendence and ineffableness, and on the other hand, the ability of the human soul to reach perfect union with God in spite of his incomprehensible nature.

Before looking at Judeo-Christian scripture it should be observed that to Jews as well as Christians, most Biblical stories have represented not only outer historical occurrence but also revelations about the characteristics of absolute reality whose symbolism was meant to be contemplated. Since Origen of Alexandria (185-253) theologians have formally distinguished "four interpretations of the Holy Scripture": the literal, semantic, allegorical and anagogical (leading the initiated towards seeing God).

In Exod 3:14 God seems to introduce himself to the Children of Israel by identifying himself as Being as such. He gives his name as: "I am that I am: and he said, Thus shalt thou say unto the children of Israel, I AM hath sent me unto you." His being is near as well as far; it fills heaven and earth (Jer 23:23-24), and goes beyond it all such that " the heaven and heaven of heavens cannot contain thee". (1 Kgs 8:27) God is so far beyond the limits of everything humans know that it is prohibited to depict him using any image whatsoever from our cosmos. (Exod 20:4)

In the Hebrew Bible JHVH does not show himself directly to anyone. When he speaks to his prophets, he hides in a dense cloud and/or in fire (Exod 19:9 and 18), or else in darkness, as in Exod 20:21: "And the people stood afar off, and Moses drew near unto the thick darkness where[in] God was." This passage is important to remember because of the mass of scholars who maintain that when Denys and other mystics talk about divine darkness they use Platonic language; yet in reality they refer explicitly to this passage in Exodus. Another important episode is described in Exod 24:15-18. God appears on Mount Sinai in a cloud. To the Israelites he looks like "devouring fire on the top of the mount". Nonetheless God calls Moses and the prophet enters "into the midst the cloud", climbs the mountain and stays there "forty days and forty nights" (which is symbolic of a very long time).

Traditionally, two reasons are given to explain why God veils himself in fire, clouds, and darkness: Either that he is invisible (1 Tm 1:17 and 6:16, and Col 1:15) or that to see him face to face is to die. (Exod 33:20) Those who are pure and whom God chooses however, are permitted to see him indirectly or in passing.

In this latter episode God's glory passes by Moses; the Lord protects him from viewing his face but he allows him to see his back as his glory disappears. Isaiah is another prophet who is granted a glimpse of God. After having seen him, he fears that he will die because he was impure when he saw the Lord. But an angel purifies him and he lives. (Isa 6:1-7) At the occasion of sealing the covenant between JHVH and the Israelites, God even grants seventy four elders at once to see him from a distance (only Moses is allowed to approach). (Exod 24:9-11)

Thus even in the Hebrew Bible God's nature does not prevent all humans from being able to see him. There are, however, stringent prerequisites for being allowed to behold the divine. And even then the image resists grasping, for it presents itself only in passing. Osborn paraphrases Philo as explaining Moses' view of God's back thus: "From here it [the soul) comes to the greatest good of all, to grasp that the being of God is beyond the grasp of every creature ... To see him is to know that he is invisible."

The New Testament goes a step further. Rather than merely granting a rare chosen one a glimpse of the Lord, it talks about an intimate and ongoing, at times complete union of the believer with the divine in an inner kingdom of God. Through Jesus, it is said, the faithful can become children of God (Rom 8:14) who are born 'not of the flesh but of God'.(Jn 1:12-13) Then they are able to fulfill his command: "Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect." (Mt 5:48) Jesus assures his disciples that not only will God's spirit be with and in them, but: "I am in my Father, and ye in me, and I in you." (Jn 14:20) This is how Christ wants it to be, for: "He that abideth in me, and I in him, the same bringeth forth much fruit." (Jn 15:5) St. Paul fulfills his wish and the result is his famous exclamation: "I live, yet not I, Christ lives in me." (Gal 2:20) Starting with Athanasius, many Christian mystics have summarized the Good News by proclaiming: "The Word became man that we might become divine."

Putting the Old and the New Testaments together, one ends up with many children of God who strive to follow and become completely one with a God who became man, but whose divine nature is utterly ineffable and transcendent. It seems that the natural result of such endeavors is Via Negativa. For, like Moses, Christians are called to purify themselves and enter the dark cloud wherein the inconceivable God is found. Will they not talk about the meaning of this cloud? And will they not share their experiences of how they managed to enter it and what they experienced therein?

2. Hellenistic Roots

Although the Bible supports the development of Mystical theology, many theologians over the centuries have spoken of the "Pagan" (i.e. Hellenistic) roots of abstract Christian contemplation and the corresponding teachings. Indeed, it has to be admitted that Greek culture had a tremendous influence on Christianity. This is quite obvious not only in the Gospel according to St. John but also in many other Biblical passages.

Exploring all the tenets of Greek philosophy that are said to have helped shape Christian thinking is beyond the scope of this study. Suffice it to say that some Greek schools of thought, particularly Platonism, know of an impersonal divine. It is sometimes called the One and constitutes the essential nature of wo/man's soul. Through initiations into divine mysteries and introspection the spiritual nature of the mind (nous) can be realized. But there were many variations of Platonism as well as many individual Platonists whose statements vary. While some affirm the divinity of the mind, others speak of transcending any concept of individual souls.

Supposedly such terms as the negative way, the mystic way, the purgative, illuminative, and unitive ways were all introduced into Christianity from Neoplatonism. Nevertheless one should not conclude that they are un- Christian, as perhaps especially Protestant theologians are prone to think. For how was Christianity born? Jesus did not found "Christianity". He was a Jew and the head of a Jewish movement which was rejected by the vast majority of his own people. In order to survive, the sect depended on a fusion with Greek culture. This was possible because his teachings already contained many elements that were akin to Hellenistic thinking. One must not forget that the two cultures shared the same territory. Thus the more Hellenistic Christians were able to expand upon certain teachings of Jesus without introducing anything completely alien. Perhaps one can characterize Christianity as the marriage of a certain Jewish movement with Greek thought. Without Judaism and Greek philosophy it is doubtful whether "Christianity" would have ever been born. The Jesus sect would probably have been just another Jewish movement that came and went, much like the Essenes.

A good example of the role Hellenism played for the Via Negativa is the development of the idea of the soul's divinization. One thing all Negative Mystics have in common and the reason why many discover the Negative Way even if no one tells them about it, is that they strive for the perfect divinization of their souls.

Where did this idea come from? Many theologians would agree with Irénée-H. Dalmais: "The vocabulary of divinization is foreign to Biblical language, which is concerned about preserving the divine transcendence as an absolute." Dalmais goes on to express amazement that the idea even arose in Christianity. To explain why it did and was able to stick, he proceeds to quote one Biblical passage after another that proves his opening statement utterly wrong. These quotes fall into three main areas:

(1) There is the passage in Genesis where God "created [wo/]man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them." And when they have eaten of the tree of wisdom they are expelled from the garden of Eden because: "Behold, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil: and now, lest he put forth his hand, and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live for ever: Therefore the Lord God sent him forth from the garden of Eden". (Gen 1:27 and 3:22-3) Yet, some time later, God does not seem to mind company in his divinity for he sends his son to grant believers precisely the eternal life which would make wo/man completely "as one of us". (Nonetheless Dalmais asserts that it is a characteristically Greek idea to think that possessing eternal life makes one divine.)

(2) The Bible has much to say about Christians being God's adopted children and heirs to his kingdom, not unlike Jesus being God's son. (Gal 4, etc.)

(3) There is Jesus' command: "Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect." (Mat 5:48)

It is a widespread opinion among Christian theologians that the Greek Fathers were more mystical than the Roman Fathers. But that does not mean that they introduced foreign concepts. As far as I can see, Hellenistic Christians did no more than three things:

(1) They recognized these teachings for what they were: the proclamation of the soul's capacity to become completely divine.

(2) They placed these teachings in the very center of their faith, regarding them as the goal of a Christian life and the only end which could satisfy wo/man's spiritual nature. The Roman Fathers on the other hand, pushed divinization as much to the background as they could. Instead they stressed a saintliness of strictly human ethics and the Jewish roots of Christianity. As will be explained below, divinization did not fit well with their concerns. So they termed the idea "pagan" and dispensable because it matched Hellenistic philosophy. Nonetheless the Church could not ban the concept completely because it is unmistakably rooted in the Bible. Instead theologians distorted its content to the point of rendering it unrecognizable. They invented an indissoluble difference between divinity by nature (as in God) and by gift or grace (as in humans). Yet, even if eternal life and divinization were a free gift, it is by definition for ever and cannot be revoked; i.e it becomes one's nature. The Bible itself likens it to a fruit that one eats, that is absorbed into one's body and changes everything irreversibly. Whether one steals the fruit or it is given, does not seem to change the outcome.

I would conclude that Hellenism enabled Christians to accept Biblical teachings which the Roman Fathers later distorted.

(3) It seems that Hellenistic Christians were much less afraid than their Jewish brethren to share their revelations. While St. Paul and many others before and after him remained silent about much that was revealed to them, Greek influence may have encouraged others to speak their truth. For the Greeks had at this point a great tradition of seeking verity at all cost and in a very public manner. They were not ruled by a wrathful God who drew a strict boundary around the secret of his being and who promised to kill anyone who would willingly or accidentally penetrate his hiding place. (Cf: Exod 19:12-3)

Nor does it seem like Greeks were afraid of how truth might impact their social structures. They had already learned to appreciate some degree of democracy and, in Egypt, of women's equality. Since the earliest centers for Christian learning were Alexandria and Athens, not just Greek but also Egyptian culture had an enormous influence on early Christianity. Perhaps these factors made "Egypto- Hellenistic" Christians less afraid when finding a truth that divinized the soul, whether male or female, and made God inaccessible to human concepts and categories, as it were, lifting the Uncreated out of human control or monopoly.

That such a truth has repercussions on the social aspect of the Church becomes quite evident in church history. Where and when ever such truth was allowed to be sought and expressed, it immediately inaugurated an emancipation of women. Christian Via Negativa was born at a time when women studied the scriptures in classes with renowned teachers and were allowed to express themselves as deaconesses and other church officials, prophetesses, teachers, missionaries, nuns, hermits, lay recluses in their homes, etc. But the more Roman the Catholic church became, the more it strove for a powerful, centralized, institution and an orderly all male hierarchy. That meant that mysticism and women (whom Christian mysticism tends to liberate) had to be kept in their "orderly" place, i.e. clearly subordinated to the male institution. To achieve this truth itself had to be controlled and guarded jealously.

3. Negative-Mystical Theology During the First 500 Years

It took a few centuries and the help of the Roman empire to achieve the goal of women's "orderly" subordination. First of all the egalitarian Greek influence had to be relegated to a decorative position. Instead of it the Jewish roots, which were far more conducive to maintaining a patriarchal power structure, were declared to be the only true Christian heritage. Yet "Christian Platonism" was not easily eradicated for it was justified by too many Biblical passages.

Mystical theology, suffered its first major defeat at the Council of Nicea in 325. Here it was decided that God created the world ex nihilo. This was a direct rejection of the Platonic teachings about an essential kinship between the divine and the soul which is realized in contemplation. In contrast to this, the patriarchs sought to maintain an essential indissoluble gulf between God and his creation. This had direct repercussions on Christian practice. The soul was no longer expected to become completely divinized by contemplating God and finding him to be one's true nature. Instead the believer was to strive for ethical perfection and become an immaculate image of the selfless, suffering, obedient Jesus. It was no longer said that God had become human so that humans could become divine. Rather it was asserted that people could not become any more divine than imitating God's human incarnation. Louth describes the theological development that the council of Nicea inaugurated as being clearly anti- mystical. This is perhaps not surprising, considering that the emperor Constantine called it not for mystical reasons but in order to achieve uniformity of doctrine throughout the empire which would serve as a basis for the centralization of the Church's power.

St. Gregory, bishop of Nyssa, played a major and somewhat schizophrenic role in this development from free mysticism to orderly institutionalization. He was not only a very influential man in the Church but also symptomatic of what was going on in the fourth century. Being quite conscious of the discrepancy between Christianity's Jewish and Hellenistic roots and its dependency on both, he sought to find a compromise between them. His mystical side was drawn to Christian Platonism. But, as Lees puts it, his church functionary side saw in it "an immediate threat to the consolidation of the Christian church".

His theology was to influence all future mystical theologians and it reflects many of the conclusions the Blessed Angela came to. The teachings of the bishop of Nyssa are by no means anti-mystical but they transcend neo- Platonism in a "negative way", much like Buddhist sunyata (emptiness) transcends Hindu atman-brahman (God-soul). The Platonic Christian soul is divine and able to know the transcendent God in a definitive and final way. It can actively work towards such knowledge by uniting so to say its "inner" divinity with God's "outer" divinity in contemplation. To St. Gregory on the other hand, the soul is not part of God but part of creation. As the whole universe, it is not only created out of nothing, in the last analysis it is nothing. In speaking of Moses' meeting with God in the burning bush (Exod 3:2) Gregory declares: It seems to me that at the time the great Moses was instructed in the theophany he came to know that none of those things which are apprehended by sense perception and contemplated by the understanding really subsists, but that the transcendent essence and cause of the universe, on which everything depends, alone subsists.

It cannot be said much more clearly: the soul and the world have no real own being and if one desires to see absolute reality, one has to leave behind all one can contemplate, which includes God's existence. "For as much as the stars are beyond the grasp of the fingers, so much and many times more does that nature which is above all human minds transcend our earthly thoughts."

Clearly these teachings are not the first thing people need to hear about God and the world. The Christian path does not start out with an ever deeper penetration into divine darkness until one sees the incomprehensible God whom no soul can see because no soul truly exists in the first place. So Gregory shortens his mystical theology and the result is an anti-mystical theology that sounds like this: The soul is a created thing, defiled by sin. God is beyond wo/man's reach, except in his human form, Jesus. All humans can do to approach God is emulate his son. Complete union with God is impossible.

This is the part of Gregory's teachings that allowed the church institution to take Christianity out of the hands of the people and deposit it into official controllable shrines. He does so at a time when many Roman citizens convert to Christianity for no other reason than that it is the preferred religion of the emperor. Since the prosecutions have stopped; becoming a Christian is no longer a question of life and death. The parishes and the church institution are becoming much more worldly. From this point on those who want to dedicate their lives to God leave the cities and retreat to the desert. There they seek the same austerities to which they were formerly exposed in the towns. Thus the Christian community becomes split between worldly lay followers and more earnestly dedicated renunciates. Before then there was one unified theology for all, of which all Christians were worthy by virtue of risking their lives for it. But now there arises the possibility of Roman citizens converting for personal gain. They are proud already and not in need of deifying their egos. It seems that St. Gregory does not want to throw the pearls of the Kingdom of Heaven before the swine of merely nominal Christians. And so he develops two strands of theology which might rightly be called 'exoteric and esoteric'. The real treasure is meant only for earnest seekers of God. These he encourages not to take his anti- mystical teachings too seriously:

All you mortals who have within yourselves a desire to behold the supreme Good, when you are told that the majesty of God is exalted above the heavens, that the divine glory is inexpressible, its beauty indescribable, its nature inaccessible [all things he teaches] do not despair at never being able to behold what you desire. For you do have within your grasp the degree of knowledge of God which you can attain.

To the true children of God the fact that the soul is a created and defiled entity that will never become God does not mean that they cannot be united with God. It means that mystical union will be achieved in an ecstasy that is not only an out of body experience but also, so to say, an out of soul experience. Or, as Lees puts it: "the soul's abandonment of self is at once an initiation into a higher state of perfection." Because the soul is not God, and the Absolute is not any of the human ideas about it, all human concepts of soul as well as God have to be transcended in order to become united with the Uncreated.

Similarly, that no final and complete union with God is possible does not mean that the soul cannot be completely divinized. It just means that its divinization will never come to an unsurpassable end because there is no end to the absolute. Paradoxically, God's unchanging eternal nature does not preclude it from enormous dynamics. Since it is infinite, there is always more to see in God. And thus the divinized soul's curiosity and desire to expand will never come to an end. Rather: "...the bride [i.e. the soul) realizes that she will always discover more and more of the incomprehensible and unhoped for beauty of her Spouse [i.e. God) throughout all eternity."

The tragedy is that during the next couple of centuries church functionaries blew anti-mystical theology out of proportion while hiding the Via Negativa even from monks, nuns, and ascetics. Though waning, it managed to survive uninterrupted publicly from Clement of Alexandria to Pseudo-Dionysius and then, for all we know, it lay as if dead for about 400-600 years!

4. The Pseudo-Dionysian Corpus