Incense

Incense (sugandhadhūpa) is a substance that produces fragrant-smelling smoke when burned. In ancient India incense was usually made from extracts of various flowers or from the aromatic gums produced by certain trees. The Buddha often metaphorically equated virtue with a sweet smell.

For example, he said: ‘Of all fragrances – sandalwood, tagara, lotus or jasmine – the fragrance of virtue is by far the sweetest.’ (Dhp.55). And again: ‘The smell of flowers does not go against the wind ... but the perfume of the good person pervades all directions.’ (Dhp.54).

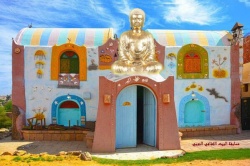

When informed Buddhists light incense and place it before the Buddha statue, they silently reflect on the importance of virtue and resolves to practise the Precepts more faithfully.

In English, sticks of incense are sometimes called ‘joss sticks.’ The word joss is derived form the Portuguese deos meaning ‘god’ and thus to call incense ‘god sticks’ within the Buddhist context is inappropriate. See Aromatherapy.

Incense is a feature of many different religious, as well as secular, rituals.

For instance, in a New Testament legend of Jesus' birth, we read how 3 travelers arrived from the east each bearing a different gift. The first was a gift of gold, but both the second and the third -- frankincense and myrrh -- are rare perfuming substances that can be burned as incense.

Incense, often arranged in a symbolic fashion, features as one of the 8 offerings on the shrine of Buddhist practitioners as an offering of perfume to delight the sense of smell. The actual burning of incense though, is an additional element -- it is used to purify negativities and thus is another kind of offering.

The aroma of incense may have the added benefit of enhancing concentration, since it can serve to mask other distinctly unpleasant or distracting odors. Also the length of time it takes for one stick to be consumed can be used to time a meditation session.

Joss

When incense sticks were first introduced to the West, they were called joss sticks. The word "joss" seems to have originated from the Portuguese word for god, deus. Chinese sometimes still use that expression, although it has taken on the meaning of luck or auspiciousness.

During a tsok (Skt. gunachakra) or tantric feast, the portion set aside for unseen beings may be "delivered" by means of the insertion of a burning stick of incense. That is one of the reasons why some people do not use food such as rice grains as a support for standing incense sticks. In that case, a good, safe (not flammable) substitute is sand made from crushed shell as is used as a digestive aid for pet birds.

In the Japanese kodo or incense ceremony, rice ash is used as a base, but Tibetan Buddhists would not normally use use it.

To 'purify' the room prior to a tantric ritual, an assisting monk may swing a censer or thurible as he passes. This is a container usually made of metal that hangs form three chains. Inside it, powdered incense that has been put on a smoldering bit of charcoal burns slowly, and the smoke escapes through pierced openings in the closed lid.

Incense does enhance the atmosphere, but also a stick of incense can be used to time one's period of meditation. Various compositions of herbs, essential oils and other elements are believed to appeal to the different deities. There is also a tradition that certain perfumes are best suited for particular objectives. Nevertheless:

The perfume of sandalwood, the scent of rose and jasmine, travel only as far as the wind,

But the fragrance of goodness travels with us through all the worlds.

Like the garlands woven from a heap of flowers, fashion your life as a garland of beautiful deeds. ~ attributed to the Buddha

Repellent

Dhoop [[[Wikipedia:Hindi|Hindi]]: plain incense) contributes the distinctive woody odor to Indian evenings, as it probably has done for at least three thousand years. Its purpose is to keep troublesome insects away, and that is how it was introduced into the Buddhist religion.

In the Buddhist context, one tradition says incense first appeared as a mosquito repellent. It seems that during one of the Buddha's sermons a monk heedlessly swatted a mosquito. Horrified, the monk certainly realized how strong is that murderous reaction -- almost a reflex.

That slap is said to have drawn the attention of the Tathagatha himself. He ordered that, in the future, incense ought to be lit in order to keep the flies away, so that people could more easily concentrate on Dharma teachings, but also to prevent the needless taking of lives. As a result, the lighting of incense became customary at teachings and other gatherings.

Smoke Offering

Another type of scented smoke offering is called, in Tibetan, sang-sol. According to Me-Long: The Newsletter of the Council for Religious and Cultural Affairs of H.H. the Dalai Lama (no.6, April 1990):

"It is not clear whether the Tibetan custom of offering incense originated in India or not, as only two references to such practice can be found in the Indian texts. It is mentioned in the Guhyasamaja Tantra that one should know about the three kinds of fragrance. The other reference is to be found in the story of Bhadri of Magadha, which tells of how she invited the Buddha to her house and made offerings of smoke to him from the roof."

According to the writings of various scholars, it seems that incense offering was carried out in Tibet from very early times when the teacher Tonpa Sherab, founder of the Bon religion, first came from Zhang Zhung to spread his doctrine in Tibet.

The oldest extant text on incense offering dates back to the eight century, when the Indian master Padmasambhava came to Tibet and built Samye monastery. This manual, containing detailed instructions on how to perform the ritual, was then hidden by him to await discovery at some appropriate juncture in the future. Several centuries later, two Treasure masters (tertons), one from northern Tibet and another from the south, discovered and revealed it.

Based on this Treasure (terma) text many Nyingma, Kagyu and Sakya lamas composed the incense offering. Later, at the time of the third Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso, a lama by the name of Yeshe Wangpo, wrote a text on the incense offering from the Gelugpa point of view.

Subsequently, three works were written on the subject by Panchen Lobsang Chogyen (1570-1662) and another by the fifth Dalai Lama.

The Ritual

The Incense offering should be done in the morning on a clean and elevated outdoor site, free of insects; either on a hill or the top of a house and inhabited by many local gods and nagas. If performed during a festival, all the inhabitants of a locality may assemble and, at the end of the offering, stand in a row and throw a handful of tsampa (roasted barley flour) in the air. As this is usually a happy occasion, a dance often follows. In the summer, incense offering is often associated with picnics on top of mountains. It is closely linked with the hanging of prayer flags from trees or tall poles, especially on the third day of the new year, but also on other auspicious days.

The incense should be burned in a large urn-shaped burner (sang-khun) and should not have been trampled by people or animals. Wood, not coal, should be used as fuel and the substance to be burned as incense should be fragrant, such as the leaves of fern or juniper, or the branches of coniferous tree, rhododendron, and red or white sandalwood. In addition, tsampa, butter, sugar, and medicinal plants, and other substances free from the taint of alcohol, onion or garlic are burned.

When offering incense, people should examine their motivation and

reflect that by making this offering to lamas, meditational deities and religious protectors, they will accumulate merit, which they should dedicate to the benefit of all sentient beings. If they have any

specific requests, such as prayers for longevity or the removal of

obstacles to religious practice, they should be made at this point.

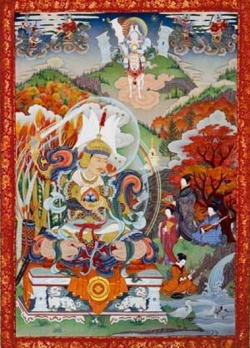

Next the practitioners take refuge, meditate on the four immeasurable wishes, love, compassion, joy, equanimity, and visualize themselves as deities. The objects to be offered are then blessed, rid of their ordinary appearances and transformed by meditation, gestures, and mantras into an inexhaustible source of great bliss which will please those to whom they are offered.

The offering ends with the practitioners asking the deities to forgive them for any mistakes in the performance of the ritual, such as improperly or incompletely reciting the words of the text. The deities are then asked to return to their abodes and auspicious verses are recited."

Incense offering can thus be performed as an elaborate religious

ritual, an offering of a fragrant purified of its ordinary qualities

and appearance to lamas, meditational deities, religious protectors,

nagas and local worldly gods. The offering is intended to please the

deities, who rejoice at the merit of those making the offering.

However, incense offering can also be performed simply because it is an ancient custom, and a traditional means of purifying the atmosphere. Incense offering is also done to mark the passing away of important people, lamas or officials, and in these ways it is a practice common to both Buddhists and Bonpos."

Incense Initiation

When the first Western woman, Gelongma Palmo (sponsored by the 16th Gyalwa Karmapa and the offices of Chinese Ch'an preceptor, Ven. Ming Chi of Hong Kong) was acknowledged to have completed the requirements as a renunciate monk, she

". . . had first taken the bodhisattva vow, the promise to help all beings attain enlightenment:

However innumerable beings are, I vow to save them;

However inexhaustible the passions are, I vow to extinguish them;

However immeasurable the Dharmas are, I vow to master them;

However incomparable the Buddha truth, I vow to attain it."

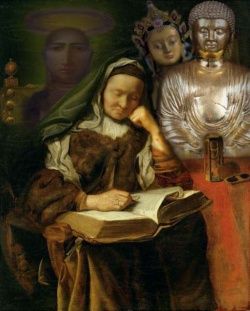

Then "A lighted stick of incense was implanted in the crown of your head. The incense stick burnt down into the scalp. You felt no pain. You recalled the Buddha Amitabha, and entered into a deep samadhi. You sent a photograph of yourself participating in this ceremony. You are dressed in a black robe for the occasion. Your face, as always, is translucent. The eyes are far seeing. The impression is of a bride, a woman wedded to an idea of truth far beyond the reach of others."

Some Arab, Persian and Indian women perfume their hair and clothes by standing over smoking aromatic substances. The rarest is aloeswood or oud, also called agar. It is also an important component of Tibetan incense, along with juniper, sandalwood and clove.

More about aloeswood incense (called Shin-kaku in Japanese stores.)

Aboriginal Americans also do smudging or smoke purification rituals, and offer sweetgrass (Hierochloe odorata) -- usually available in braided bunches -- and tobacco, cedar, sage and a variety of other plants, by burning them.

Khenpo Konchog Gyaltsen Rinpoche in a discussion on the shrine offerings says incense symbolizes morality -- the perfection of virtue [Skt.: shila):

"Incense, which is the nature of morality, makes offerings to the nose of the enlightened beings. The enlightened beings are not attached to smell, but to our purity. All people respect those who have kept moral ethics well. It doesn't matter who they are, they get respect because they are trustworthy and dependable. That kind of person gives a good smell, good odor, and people are attracted to that. not only people, but the qualities of enlightened beings are also attracted by that morality. It is their foundation/basis, like the ground which grows ... the "crops" of ... enlightened qualities."

Fortune-telling, or Prognostication by Incense

According to a Chinese tradition, the burning sticks, when set upright as in a burner like that at the top, or stuck into a bowl of sand [never use rice for this purpose] can be used as a fortune-telling device. You concentrate on your question as you light the 3 sticks, or just examine the remains of the incense that you have left to burn on the shrine. The outcome depends on the pattern made by the long, medium and short sticks that remain when the stick has gone out by itself.

The incense [pattern] of Good: I I I tieh liarn hua hsiang

This is also Good I I I hsien jui hsiang

The incense of increasing Luck: I I I tseng fu hsiang

Auspiciousness I I I kou sher hsiang

Incense of Bad outcome I I I eh-shih hsiang

Incense of safety I I I peng on on hsiang

Incense of Longevity I I I tseng shou hsiang

Incense of Illness I I I jir bihng hsiang

Incense of Theft I I I tao tsei hsiang

Incense of Prosperity I I I tseng tsai hsiang

Incense of Death I I I hsiao fu hsiang

~ thanks to a conscientious informant relying upon her grandmother's tradition

Russell's Tibetan Incense.

_____________________________________________________________

Frankincense and myrrh: resins from the shrubs Boswellia sacra (frankincense) and Commiphora myrhha. Today, the main sources are Arabian Gulf states of Africa and Asia, from which the products are shipped to Bombay, India.